Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

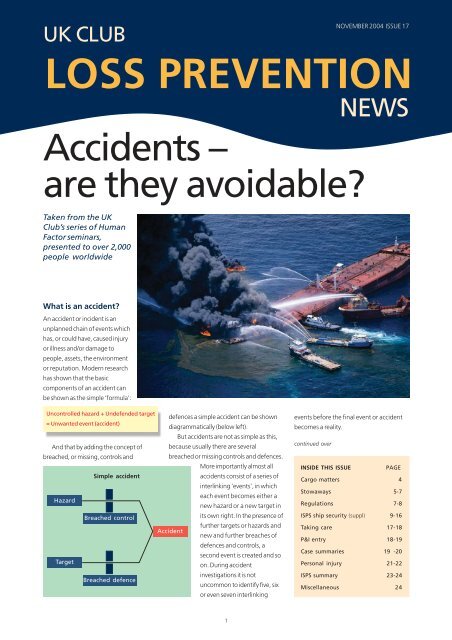

<strong>UK</strong> CLUBNOVEMBER 2004 ISSUE <strong>17</strong>LOSS PREVENTIONNEWSAccidents –are they avoidable?Taken from the <strong>UK</strong>Club’s series of HumanFactor seminars,presented to over 2,000people worldwideWhat is an accident?An accident or incident is anunplanned chain of events whichhas, or could have, caused injuryor illness and/or damage topeople, assets, the environmentor reputation. Modern researchhas shown that the basiccomponents of an accident canbe shown as the simple ‘formula’:Uncontrolled hazard + Undefended targetdefences a simple accident can be shown= Unwanted event (accident)diagrammatically (below left).But accidents are not as simple as this,And that by adding the concept of because usually there are severalbreached, or missing, controls andbreached or missing controls and defences.More importantly almost allSimple accidentaccidents consist of a series ofinterlinking ‘events’, in whicheach event becomes either aHazardnew hazard or a new target inBreached controlits own right. In the presence offurther targets or hazards andAccidentnew and further breaches ofdefences and controls, asecond event is created and soTargeton. During accidentinvestigations it is notBreached defenceuncommon to identify five, sixor even seven interlinkingevents before the final event or accidentbecomes a reality.continued overINSIDE THIS ISSUEPAGECargo matters 4Stowaways 5-7Regulations 7-8ISPS ship security (suppl) 9-16Taking care <strong>17</strong>-18P&I entry 18-19Case summaries 19 -20Personal injury 21-22ISPS summary 23-24Miscellaneous 241

ManageSimple event chain or incident trajectoryequation but very quickly established an‘alternative’ theory of accident causation.FIRST EVENT SECOND SET OF EVENTS FINAL EVENT Because of the triangular shape of the(ACCIDENT)basic model of the theory, it becameHAZARD(ineffectiveknown as the ‘Tripodian’ view of accidentTARGETaftercare)EVENTcausation. Basically it uses the(operator)(partial disability)‘conventional’ diagram shown below, left,HAZARDEVENT-TARGET(ignition source)(operator-burned)but adds a third component general failureEVENT-HAZARDtypes (GFTs).(fire)TARGETEVENTThis ‘alternative’ model of accident(flammable(equipmentmaterial)damaged)TARGETcausation is shown in the diagram below.(equipment)The research accepts that, properlyinvestigated, there is much in a reactivesense to be learnt from accidents. It alsoaccidents continuedThe concept of the ‘event chain’ or‘incident trajectory’ is shown above.Note the original (first) event resulted ina fire. In the presence of two new‘targets’, i.e. an operator and a piece ofequipment, the resultant double event ledwill invariably have been caused by the actsor omissions of people, which may benothing more than a simple andunintentional mistake. Such unsafe acts orunsafe conditions are generally referred toas active failures.recognises, that unsafe acts or activefailures can be reduced using tools aimedat modifying human behaviour. Theresearch suggested that the problem withattempting to learn solely from activefailures is that; (a) there are potentiallyto a badly burnt operator (injury) andWhile active failuresdamaged equipment (asset damage). are interesting –Accident causation – the ‘Tripodian view’Because the immediate aftercare of theinjured operator (first aid or paramedicindeed much can belearnt from them – aGeneraltreatment) was ineffective (new hazard), lot more can be learnt,failurethe operator’s injuries resulted in a partial and more effectiveReducetypesdisability (final event).remedial measures putHazardsReverting to the simple accident in place, by addressingdiagram and the ‘formula’ in the text box the sick camel in theon the front page, if one of the controls or first place.Accidentsdefences had not been breached there ConventionalUnsafe acts IncidentsLTIs etcwould not have been an accident. If wisdom (below, left),detected, the resultant ‘near-miss’ or dictates that in orderLearn from‘dangerous occurrence’ could still have for an accident toSpecificsituationsbeen reported, investigated and acted happen, defences ofDefencesupon as if it were the real thing.The usual mechanism, whereby controlsand defences are breached, is an unsafeact by an individual at the sharp end.Occasionally, they may be breached by aninherent unsafe condition but these toosome kind will havebeen breached, usuallyby an unsafe act, carried out in a specificsituation and in the presence of hazards ofsome kind.What changed this long-establishedview, which as a basismillions of them; (b) they will rarely berepeated in the same way, and; (c) thecircumstances in which they occurred willnever be exactly the same. Moreimportantly the research established onceAccident causation – the ‘conventional view’Hazardsfor the new model isstill correct, was somehighly originalresearch sponsored byone of the oil-majorsand for all that the ‘sick camel’ could bemade considerably healthier by managingwhat are called the general failure types(GFTs) of which there are just eleven. Usinga medical analogy, the GFTs could beUnsafe actsand carried out at two considered as the vital organs of theAccidentsmajor universities, oneIncidents‘safety body’. If properly managed in termsLTIs etc in the <strong>UK</strong> and one in of their inherent health or strength, thesethe Netherlands. The could actually help prevent large numbersSpecificresearch originally set of accidents from ever happening at all.situationsDefencesout to establish the Once again, in medical terms it’s a bit likerole of the humanbeing in the accidenthaving a healthy heart and preventingheart attacks, or being vaccinated against2

Policymakerspneumonia or ‘flu’ – all designed toprevent illness in the first place. Thus ratherthan acting in response to an incident weseek instead to act before an incident.The research, delved deep into thecausation theory in order to establish aconcrete link between breached defencesand controls, and active and latent failures,thus the Tripod causation model was born(see diagram below).The interesting point about this model,is that it introduces two new elements intothe causation chain. First it provides alinking mechanism, known as theprecondition, though sometimes referredto as the ‘psychological precursor’,between the active and latent failures.Secondly, it introduces the policy makerat the very start of the chain, thusillustrating the clear relationship betweencommitment by the policy makers at thebeginning of the chain and the results atthe end of the day.No commitment = No effective safety orHSE management systemBy comparing the diagram of the Tripodcausation model and the simple accidentdiagram on the front page, it shouldbecome obvious that the link between thetwo is established through failed defences(for the target) and failed controls (for thehazard). The combined accident model,known as the Tripod-BETA tree, completewith all basic components is shown in thediagram (above right).Bearing in mind that any accidentconsists of a series of interlinking events, acompleted accident tree can beexceedingly complex indeed.Active failuresBoth defences and controls are breachedby ‘active failures’. Active failures are thefailures close to the accident event thatdefeat the controls and defences on thehazard and target trajectories. In manycases, these are the actions of people, i.e.unsafe acts. Human errors are implicatedin at least four out of five active failures,LatentfailuresPreconditionsPreconditionsTripod causation modelActive failures(incl. unsafe acts)PolicymakersPolicymakersLatentfailures LatentfailuresHAZARDTARGETPreconditions but human error as we have already seenis a broad term that includes a number ofdifferent sources of error.Not all active failures are humanactions. Physical failure of controls anddefences also occur due to conditions suchas over-stress, corrosion or metal fatigue.These are often referred to as ‘unsafeconditions’. Having said that, humanactions are often implicated ascontributory causes to this form of activefailure but they are not, in themselves,unsafe acts. For instance, a designer mayhave failed to identify the need to use aparticular high-tensile material in a specificthe future potential for adverse effects ofdecisions may not be fully appreciated, orcircumstances may change that alter theirlikelihood or magnitude.The accident-producing potential oflatent failures may lay dormant for a longtime, only becoming apparent when theycombine with local triggering factors –active failures, technical faults, abnormalenvironmental conditions or abnormalsystem states; some of which even the bestHSE management systems will haveabsolutely no control over whatsoever.Rather than dealing with an infinitenumber of active failures, it is reassuring toA defining characteristic of latent failuresis that they have been present within the operationbefore the onset of a recognisable accident sequencecircumstance, thus sometime later causingcomponent failure.Latent failuresAs already mentioned, latent failures are the‘vital organs’ of the safety equation. Latentfailures are deficiencies, or anomalies, thatcreate the preconditions that result in thecreation of active failures. Management(the so-called policy or decision makers)decisions often involve the resolution ofconflicting objectives. Decisions taken usingthe best information available at thatmoment prove to be fallible with time. Also,Failed systemdefences/controls IncidentThe Tripod-BETA treeActivefailuresActivefailuresFailed controlFailed defenceEVENTnote that there are just eleven latentfailures on which to work to ensureabsolute good health.The eleven latent failures, whichconstitute the general failure types (GFTs)are:■ HARDWARE■ DESIGN■ MAINTENANCE MANAGEMENT■ PROCEDURES■ ERROR-ENFORCING CONDITIONS■ HOUSEKEEPING■ INCOMPATIBLE GOALS■ COMMUNICATIONS■ ORGANISATION■ TRAINING■ DEFENCESThe Club’s new DVD No Room For Errorexamines these in detail ■3

cargo mattersCarriage ofcoal cargoesSeveral incidents have highlighted furtherpossible problems arising out of the ‘safecarriage of coal cargoes’.It appears that there are still possibleproblems relating to the informationprovided by the shipper and/or hisappointed agent. The IMO Code of SafePractice for Solid Bulk Cargoes clearlystates that the master shall be provided inwriting the characteristics of the cargo andthe recommended safe handlingprocedures for loading and transport.In a recent loading in the Far East, themaster was presented with a shipper'sdeclaration which gave a brief outline ofthe cargo characteristics which includedthe following:“This cargo is not considered liable toemit significant amounts of methane. Thiscargo is not considered liable tospontaneous combustion.”The master had studied the relevantentry in the IMO Code and followed therecommendations of the Code under theheading ‘General requirements for allcoals’.For the first 24 hours of the voyage theholds were surface ventilated to releaseany methane evolved from the cargo. Nomethane was detected in this period andthe hold ventilation was closed. The holdatmospheres mentioned were monitoredfor methane, carbon monoxide and oxygentwice daily in accordance withrecommended procedures. However,within four days of sailing from the loadport, it was noted that the levels of carbonmonoxide in some of the cargo holdsshowed a steady rise. The master reportedthese figures in his daily report andrequested advice.The results of these tests indicated thatthere was a possible spontaneous heatingproblem with the cargo and the masterwas advised to follow therecommendations of the IMO Codedescribed under the heading ‘Specialprecautions self-heating coals’.In particular, he was advised tocompletely close down the cargo spaces,sealing all joints in covers, ventilators, etcwith Ramnek tape. He reported airmovement through the coaming drains andthese were also closed. Within a shortperiod of time, the levels of carbonmonoxide and oxygen began to fall and thisfall continued through the voyage.Discharge was completed with no problems.In respect of coals liable to spontaneousheating, the Code recommends that thehatches should be closed immediately aftercompletion of loading in each cargo space.The atmosphere in the cargo spaces shouldbe monitored and, if the carbon monoxidelevel shows a steady increase, then thecargo spaces should be completely closeddown. The covers could also be additionallysealed with suitable sealing tapes.It should be noted that even well-fittedhatchcovers may be weathertight to rainand seas over the deck. However, withvarious rolling movements of the ship, thecovers may not be ‘airtight’. Leakage of airinto the cargo space will then assistspontaneous heating of the coal.Subsequent heating of the coal will set upthermal movements within the cargospace, hot products of combustion out ofthe space and a fresh supply of oxygen intothe space to assist further oxidation andheating of the coal.It is suggested that ships chartered tocarry coal cargoes should be provided withan adequate supply of sealing tape tomaintain effective sealing of the cargospaces.<strong>Members</strong> should note that this incidenthighlights the need to closely follow therecommendations of the IMO Code relatedto the carriage of coal ■...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................<strong>UK</strong>RAINEDischarge ofbagged riceThere have been several recent caseswhere ships have faced difficultiesdisharging cargoes of bagged rice inUkrainian ports due to the cargo beingallegedly of an unsound condition.The Ukraininan ports’ State SanitoryAuthority (SSA) boards ships immediatelyon arrival to inspect the apparentcondition of the cargo. If mould is found tobe present, even if only on the cargopacking, the SSA will prohibit discharge ofall cargo from the holds where the mouldybags were found. The position held by theSSA in these circumstances is a tough oneand it is difficult to negotiate with themand the cargo receivers. The cargoreceivers will reject the cargo claiming itdoes not correspond to the clean bills oflading on the grounds of the SSA’s findings.Occasionally, mould may be apparent onlyon the outside of the bags, but in manycases the rice adjoining the material of thebag is also affected. It should be stressedthat it makes no difference to the SSAwhere the mould was found, or thepossibility of segregating sound from thedamaged bags, as further discharging ofsound bags is often forbidden.This problem concerns mainly shipsarriving from Chinese load ports, wherethe cargo is occasionally packed in singlewoven polypropylene bags (not doublebags) and is stored (prior to loading) instacks in an open area covered only bytarpaulin. As a consequence, some bagsbecome wetted / collect moisture prior toand during loading operations. During along passage from China to the Black Sea,stowage of the cargo inside the holds –ie. without sufficient vertical andhorizontal channel ventilation – will alsoadd to the development of mould.<strong>Members</strong> should be aware of theextreme action being taken by theUkrainian authorities and be particularlycareful when loading this type of cargo,especially from Chinese ports at this time ■4

stowawaysSINGAPOREStowawayregulationsWe have been advised that the SingaporeAuthorities will not permit stowaways tobe landed in Singapore for repatriation,even if these stowaways possess validtravel documents or passports.Ships prior to their arrival must declarethe presence of stowaways onboard tothe Singapore Authorities. On arrival, theship must proceed to the quarantineanchorage for immigration and portformalities clearance where the masterwill have to sign a bond of US$10,000 foreach stowaway.The authority will enforce these bondsif the stowaways are found missing fromthe ship prior to the departure clearance.The ship must therefore ensure that thestowaways are kept locked onboardduring the entire port stay.Ships whilst at the quarantineanchorage are not allowed to carry outcargo operations and/or receive stores orbunkers. To perform these operations, theship must shift from the quarantineanchorage to a proper berth or anchorageafter the immigration and port formalitieshave been completed.We advise all <strong>Members</strong> to be fullyaware of the above and to inform theirchartering and operations departmentsaccordingly ■...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................BRAZILStowawaysfrom AfricanportsThe Club has been made aware of severalcases concerning stowaways hiding inship's rudder housings, specifically withships coming from African ports in ballast toload sugar in Brazil.Stowaways have apparently discoveredthat the void space around the rudderstock is the best place to hide from thelocal stowaway search, since this place isnot easily accessible from inside the ship.Crews should be instructed on this newstowaway strategy, intensifying thestowaway search to include the rudderhousing. Crew may have access to therudder housing by opening any of theavailable accesses in the steering gearroom.One case involved a Member’s ship,which was on a regular run betweenDjibouti and Yanbu al Bahr, Saudi Arabia.The ship was of conventional construction,but with a peculiarity in the rudder areawhich the stowaways could make gooduse of. On arrival at Jeddah anchoragewhere the ship called for bunkers, astowaway was found sitting on top of therudder assembly. This stowaway was aKenyan national, who had entered therudder cavity in Djibouti and had travelledfor two days in the cavity, less than twometres above the water line with the noiseof the propeller and steering gearconstantly in his ears. When discovered,the stowaway was barely conscious.As the stowaway had nodocumentation with him, and due todifficulties in repatriating stowaways fromSaudi Arabia, the stowaway returned withthe ship to Djibouti, where temporarytravel documentation was obtained toallow for his repatriation. Prior to againsailing from Djibouti, the master requesteda search of the rudder cavity. A mooringboat from the Port Harbour Office wasused for the inspection, with acrewmember climbing into the rudderhousing to check and confirm the spaceempty.In other cases of stowaways beingdiscovered in the rudder housing, theywere found to be in very poor health and inone case two stowaways wereunfortunately found dead.We advise all <strong>Members</strong> of this situationand recommend that crews intensifystowaway searches and ensure that hardto reach positions on the ship, like therudder housing, are thoroughly searched ■5

MOMBASA – KENYAProblems with disembarking stowawaysA recent decree, <strong>issue</strong>d by the Kenyanauthorities, states that non-Kenyanstowaways are no longer permitted to bedisembarked and be placed in the safecustody of the Mombasa Port Policepending investigation and eventualrepatriation.Non-Kenyan stowaways may only bedisembarked when a consular/embassyofficial has confirmed their nationality andthe requisite emergency travel documentshave been <strong>issue</strong>d. The stowaways will thenbe disembarked and taken directly to theairport. Unfortunately, it is almostimpossible to have necessary repatriationdocumentation on hand in time.Most embassies are situated inNairobi. Even if the officials manage tocoincide their arrival in Mombasa with thearrival of the ship, the necessary flightschedules and seats may not be availablefor the stowaways to be transferreddirectly from the port to the airport. Insome exceptional cases, Tanzanianstowaways can be removed in time, as theTanzanian consular representative islocated in Mombasa ■.........................................................................................................................................................................................DURBAN – SOUTH AFRICAStowaways – ISPS CodeTo disembark stowaways in Durban,South Africa, the following requirementsmust now be in place:■■■■Ships arriving in Durban from a foreignport are required to give 96 hoursnotice of stowaways onboardproviding the ship is ISPS compliant. Ifthe ship is not compliant with the ISPScode then this could hinder thedisembarkation of stowaways.Ships arriving at Durban whose lastport of call was a South African port,will be allowed to disembarkstowaways without giving noticeprovided that they meet with theNational Ports Authority'srequirements.Ships arriving at Durban Roads from aSouth African port that wish todisembark stowaways at the outeranchorage will be allowed to do so,provided they meet with the NationalPorts Authority's requirements.Ships leaving Durban harbour wherestowaways are found onboard afterthe ship has left the anchorage will beallowed to disembark the stowaways,provided they meet with the NationalPorts Authority's requirements.The National Ports Authority requires thefollowing:In all cases where stowaways have beenfound onboard a ship from either a foreignport or a South African port, a pre-arrivalform from the National Ports Authority ofSouth Africa must be completed by theship's local agent and forwarded, prior tothe stowaway or stowawaysdisembarkation, to:1 Maritime Rescue CoordinatingCentre, Cape Town2 Durban Port Control3 Port Security Officer, DurbanWe advise <strong>Members</strong> of the aboverequirements, which may be subject tochanges, and also advise that localimmigration requirements must also becomplied with ■.........................................................................................................................................................................................................WEST COAST USAReoccurrenceof ChinesestowawaysTowards the end of May 2004, two enteredvessels, a container and bulk carrier arrivedat Long Beach, California and Vancouver,Canada respectively. Each had sailed fromBusan, Korea, around the middle of May,one from the main container terminal andthe second from Pier 5, bulk cargo, which isadjacent to the terminal.During the voyage to Long Beach on thecontainer vessel, three Chinese stowaways,all originating from Fujian, were foundhiding in the deck container stack area.There was no evidence of any crewinvolvement in secreting the stowawaysaboard and it was suspected that they hadgained access during the vessel’s stay inBusan.In the case of the bulk carrier, sevenFujianese stowaways were discoveredhiding in a void space below the forecastleand above the fore peak tank. In this case,they alleged that crew had assisted them togain access to the vessel.During the course of investigations ittranspired that a third non-club enteredvessel had also been found in Long Beach tohave four Fujianese stowaways aboard,again hiding in above-deck containerstacks.continued over6

egulations continuedbeen very little research done on this but itis thought that excess alkalinity could be ascorrosive as excess acidity. The grade ofcylinder oil should therefore be matched tothe sulphur content of the fuel and bothowners and engine manufacturers mayhave to consider the possibility of dualcylinder oil systems.Annex VI puts the burden on bunkersuppliers to supply fuel which conforms withthe sulphur limits but the burden ondemonstrating compliance will be on shipsand their owners. The requirements tocover this aspect include retaining bunkerdelivery receipts, which will have to showthe sulphur content, of all fuels received for3 years and for the taking of what will beknown as ‘regulatory samples’ so that,should a port authority require it, it can betested to prove compliance. What is ofinterest is that IMO has decided that thissample should be taken by the continuousdrip method at the receiving vessel’s bunkerinlet manifold i.e. not on the bunker barge.Owners will also have to ensure that notonly do the crew properly segregate lowsulphur fuel but that they also properlydocument it and the change overprocedure so that the evidence is available.Retaining the documentary evidence andregulatory samples for the required periodmay require dedicated storage.Further information can be obtainedfrom The International Bunker IndustryAssociation : http// www.ibia.net...................................................................................................................................................................................UNITED STATES OF AMERICAUSCG enforcing ballast watermanagement regulationsFrom 13 August 2004, the USCG beganenforcing US ballast water managementregulations. The master, owner, operatoror person-in-charge of any ship equippedwith ballast water tanks that is bound forports or places in US waters must ensurethat complete and accurate ballast watermanagement (BWM) reports aresubmitted in accordance with 33 CFR151.2041, and signed BWM records arekept onboard the ship for a minimum oftwo years in accordance with 33 CFR151.2045. The final rule titled ‘Penaltiesfor Non-submission of Ballast WaterManagement Reports’ (33 CFR 151,subpart D, as amended 14 June 2004)implements a maximum US$27,500 a daycivil penalty and class C felony provisionsfor failing to submit BWM reports andfailing to maintain BWM records.The final rule also expands existing BWMreporting and record keepingrequirements to include all ships equippedwith ballast water tanks that transit toany US port or place of destination,regardless of whether the ship operatedoutside the exclusive economic zone (EEZ)of the US or the equivalent Canadianzone.We expect that the USCG captain ofthe port (COTP) will in most cases take atiered approach to enforcement actionsstarting with letters of warning (LOW),notices of violation (NOV), civil penalties,suspension and revocation (S&R), captainof the port orders and then, in a worst casesituation, criminal charges. Conversely,COTPs may also consider including superiorcompliance recognition programmes forthose operators who continuously showsuperior compliance with new or existingBWM requirements.The only ships that are exempt from themandatory BWM requirements under thefinal rule are:■■■Ships that operate exclusively withinone COTP zone;Crude oil tankers engaged in coastwisetrade; andShips of the Department of Defense,Coast Guard, or any of the armedservices as defined within 33 USC 1322(a) and (n).Details of sending the ballast watermanagement report form can be found onhttp://invasions.si.edu/nbic ■........................................................................................................................................................................................AUSTRALIACrew immigration clearance requirementsFrom 1 July 2004, the transitional period ofthe requirement for all crew of non-militaryships entering Australian waters to carry apassport and identity document forpresentation at immigration clearanceends.The identity document must show andconfirm the person concerned as a seafareremployed on that ship. The passport anddocument must be located on the ship as itenters Australia at a proclaimed port or aplace other than a proclaimed port, ifpermission for it to do so has been grantedby the Australian Customs Service.Under the Migration Act 1958 (Cth),authorised officers of the Department ofImmigration now have the authority toimpose a penalty on the master, owner,agent and charterer of a ship due to crewmembers' non-compliance. In one recentcase an infringement notice was <strong>issue</strong>d tothe local agent of a foreign ship for thefailure of a crew member to be inpossession of the required identitydocument. The agent has been finedAUS$5,000.00, which must be paid within28 days.In these circumstances it seems clearthat the Department of Immigration is nowdetermined to enforce the newrequirements regarding identificationdocuments. Therefore, care should betaken to ensure that all crew of nonmilitaryships entering Australian waterscarry with them the requireddocumentation ■8

ISPS – SHIP SECURITYA LOSS PREVENTION NEWS SUPPLEMENTSecurity – a shared responseGood security is teamwork – a responsibility for all onboard, not just a selectfew, to protect and secure their environment.This supplement illustrates just a few examples of the positive ways in which<strong>Members</strong>’ crews have responded to the need for onboard security and thepreventive measures used to tackle this ongoing, ever-evolving, problem.First line of defence – the gangwayRestricting the accessMonitoring visitors9Clear noticesFIRST LINES OFDEFENCE

Record keeping CheckingbaggageBody searchesTactful bodyscreeningCHECKING ONVISITORS10

ELECTRONICSURVEILLANCEClear to enterClear, precise written recordsElectronicsurveillance mayassist ships’ staffRadio communication Electronic cameras 11

KEEPING AWATCHFUL EYEVideo display of visitors and selected parts of the shipSensitive areas under continuous surveillance and recording devicesin operation on some shipsSearch/electronic surveillance of all persons and bags Issuing ships’ staff with ID badgescan avoid confusionPassenger ships– crew ID 12

Security in the homeRestricting movementon exterior stairwaysProtecting theaccommodationblockHigh securitymeasuresOpen void spaces13Frequentuse areasSECURE ENTRYPOINTS

LOCKS AND CODEDKEYPADSCoded keypads or key locks on steel doorsCoded locks oninterior doorsEmergency escape Deck lockersSounding pipes 14

CONTROLLINGSENSITIVE AREASFoc’sle areasMore foc’sle securityEngine room securityCargo securityAccess controlChecking stores 15

STAYINGAWARESecurity lighting Security applies to all onboardBeware of the dog! Preparing for the unexpectedWhat these examples cannot illustrate isthe ongoing work behind these securitymeasures. The need to practice securitydrills, to regularly audit and update securityprocedures, as well as to maintaincontinuous synopsis records – the need tobe prepared.They are not exhaustive, but showsome ways in which the <strong>issue</strong>s of safety andsecurity onboard have been tackled. Butbehind it all is the need to shareinformation and knowledge. To constantlyrefine and review the methods andequipment used, with a view to achievingthe highest standards possible................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................For further information contact:Karl Lumbers, Loss Prevention DirectorThomas Miller P&I LtdInternational House, 26 Creechurch LaneLondon EC3A 5BATel: +44 (0)20 7204 2307Fax: +44 (0)20 7283 65<strong>17</strong>e-mail: karl.lumbers@thomasmiller.comhttp://www.ukpandi.com16

taking carePANAMA CANALAccidentand cargoclaimsWe have recently noted changes in themanner in which administrative claims forvessel accidents and cargo damage arebeing processed by the Panama CanalAuthority (PCA). The organic law of thePanama Canal provides that the PCA isresponsible for damages suffered byvessels, their cargoes, crew or passengerswhile transiting the Panama Canal andwhich are caused by the negligence of thePCA. The law further provides that the PCAshall promptly adjust and pay suchdamages. The enabling statute governingthe operation of the Panama Canal by thePanama Canal Commission, USadministered predecessor of the PCA,contained a similar provision regarding thedisposition and adjudication of theaforementioned claims. For the first fewyears subsequent to its assuming full controlof the operation and maintenance of thePanama Canal, the PCA did in fact promptlyadjust and pay such damages, in line with itsoften-repeated position that the PanamaCanal would continue to be administered inthe same or better manner as in the past.We are aware of at least one claimwherein the PCA has failed or declined forreasons best known to its administrator andlegal department, to make a finaladjudication of said claim, even though thatclaim had been pending before the PCA forover 21 months. Additionally, claimantsadvised the PCA more than 10 months agothat they would not be presenting furtherinformation and documentation withrespect to their claim and specificallyrequested that the claim be adjudicated.This apparent new position by the PCArespecting the handling and adjudicationof administrative claims is a source of greatconcern because the PCA is attempting toassert that it cannot be sued until itadjudicates a claim regardless of the time it(the PCA) takes to adjudicate such claim. Ifthe PCA takes this seemingly capriciousposition to an extreme, a party, whethershipowner, cargo owner or passenger,could be waiting indefinitely for their claimto be adjudicated, without having anyother recourse under the law (asinterpreted by the PCA) to force the PCAto resolve its claim and reimburse theclaimant for any damages suffered as aconsequence of the fault of the PCA ■........................................................................................................................................................................................UNITED STATES OFAMERICAThe dangersof enteringconfinedspacesIn a recentincident, a ship'ssecond engineerlost his life whenhe entered andbecame trapped in themain engine's scavenging airreceiver. In this case, the ship reported thatthe second engineer was missing prior tosailing. Despite an extensive search byship's personnel of all areas including manysearches of the machinery spaces and themain engine, the engineer could not befound therefore it was presumed he hadgone ashore and missed sailing. Uponarrival at the next port the individual wasfound deceased behind an access door tothe main engine scavenging air receiver.It was determined that theengineer entered the scavengingair receiver alone. The reason forentering the receiver is not known,although engine maintenance wasperformed in that space whilst at thefirst port and, therefore, he may havereturned to inspect the area for tools leftbehind or to retrieve something. It appearsthat after his entry, the easily-moved,inward-opening, hinged door accidentallyclosed (see photographs). Investigatorsbelieve that at that time, the upper leftdog – due to its weight and perhaps thevibration of the door as it closed – moved,allowing its edge to catch thecircumferential lip at the opening. Oncecaught, even with the loosened fastener,the door could no longer be opened frominside the receiver. The engineer wouldhave initially had sufficient quantities ofoxygen to breath, but when the enginewas started the conditions inside thereceiver would have dramatically changedand caused the fatality.It is important to note that the secondengineer was an experienced marinerwho, it was reported, was trained andfamiliar with the ship's confined spaceentry procedure. In all previous instances,he had followed the procedures and safelyperformed maintenance inside the space.Unfortunately, on this occasion he enteredwithout informing anyone or having anassistant stationed outside.continued over<strong>17</strong>

taking care continuedMain engine crankcases, scavenging airspaces, exhaust ducting, boiler drums,furnaces, stack casings, condensers,sewage plant tanks and other systems,equipment, and components may presentpotential ‘confined space’ type hazardsthat mariners may, on occasion, notassociate as confined spaces and thereforenot take the precautionary steps needed.A confined space may be defined as anylocation that, by design, has limitedopenings for entry or egress and is notintended for continuous humanoccupancy. This definition appliesregardless of whether or not theatmosphere is explosive or toxic. Seerelated US Department of Labor,Occupational Safety & HealthAdministration information by accessingtheir website at www.osha.gov■■■■■It is strongly recommended that:All vessels complying with theInternational Safety ManagementCode (ISM) have a specific plan forentering confined spaces outlinedwithin their Safety ManagementSystem.The confined space entry proceduresinclude and identify various types ofshipboard spaces such as thosepreviously mentioned that could beencountered and which should betreated as confined spaces.Crew safety meetings address theidentification of confined spaces andprovide instruction on confined spaceentry procedures.Individual crew members that work inconfined spaces review existing entryprocedures and requirementsregularly.All other vessels and maritimeoperations falling outside of ISMrequirements develop and include intheir marine safety programmes similarconfined space identification and entryprocedures.We advise all <strong>Members</strong> to be fully aware ofthe above and to inform their ships'masters and operations departmentsaccordingly ■...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................P&I entryJAPANCompulsory insurancerequirements on non-tankervesselsFrom 1 March 2005, in accordance withthe newly amended Japanese Law onLiability for Oil Pollution Damage, all oceangoing,non-tanker vessels of 100 gross tonsor more must comply with therequirements of compulsory insurancewhen calling at a Japanese port.LiabilityThe English version of the amended Lawon Liability for Oil Pollution is not available.However the Japan Ministry of Land,Infrastructure and Transport (MLIT) hasposted a summary on its website fromwhich it is clear that the new law imposesstrict, joint and several liability on theshipowner and charterer of the vessel fordamage caused by a bunker spill.InsuranceMLIT’s summary announcement indicatesthat insurance required under the new lawmust include coverage for damage causedby bunker pollution and coverage for theexpenses of wreck removal. The amountsof insurance cover must be sufficient tomeet both personal claims and other claimsin accordance with the limits providedunder the 1976 LLMC.Charterers – which may include timecharterers but not voyage charterers – arealso liable under the law. However MLIThas confirmed that if the owner has a ClubCertificate of Entry onboard the vessel, thecharterer will not be required to supplyanother insurance certificate.What <strong>Members</strong> should do inorder to comply with the newrequirements■Carry the relevant certificate ofinsurance onboardFor owners insured with any of the18

■International Group of P&I Clubs, theClub’s Certificate of Entry will beaccepted. However the Certificate ofEntry must be an original.Report the status of insurance beforeentering a port or certain designatedsea areas.A report form must be filled out and faxedto the relevant district transport bureaubefore noon on the previous working daybefore the entry of the vessel in aJapanese port or entry into certaindesignated sea areas, these being TokyoBay, Isewan Bay and the Inland Sea. (Fordetails of the bureaux and the report formwhen it is available, visit MLIT’s website).MLIT’s announcement appears to indicatethat this notification requirement alsoapplies to CLC tankers.This article provides preliminary advicein response to queries from <strong>Members</strong>,but as noted above, since an Englishversion of the law is not available,<strong>Members</strong> are encouraged to visit the MLITwebsite for updated information and todownload the report form, when it is madeavailable. The website also includes theMLIT’s contact details and can be found atthe following address:www.mlit.go.jp/english/maritime/insurance_portal.htm ■..........................................................AUSTRALIAConfirmationof P&I entry<strong>Members</strong> who are trading to Australiashould be aware that the AustralianCustoms Service (ACS) is now insisting uponsighting a confirmation of ships’ P&I entryprior to granting them permission to sailfrom any Australian port.We have been advised of cases whereships have been delayed until the P&I Clubin question has provided a faxconfirmation. ACS stated that they wouldaccept fax copies of the confirmation until20 April 2004, after which ships should beable to produce an original certificate ofentry ■...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................case summaries(1) Mayban General Assurance BHD,(2) AMI Insurans BHD, (3) Malaysian NationalInsurance BHD, (4) Sharikat Takaful malaysiaBHD -v- (1) Alstom Power Plants Ltd, (2) AlstomT&D Ltd [2004] EWHC 1038 (Comm)-QBDQuery: Is inability of goods towithstand the ordinary perils of a seavoyage a new category of inherentvice?A transformer was shipped from EllesmerePort, <strong>UK</strong>, to Malaysia under an ‘all risks’cargo policy. When it arrived, it was foundseriously damaged and had to be returnedto the <strong>UK</strong> for repairs . The shipper lodged aclaim against his insurer alleging loss causedby some unusual event in the course of thevoyage. The insurers rejected the claimciting inherent vice on the basis of thetransformer’s inability to withstand theordinary incidents of carriage by sea fromthe <strong>UK</strong> to Malaysia during the wintermonths.On the facts, the weather conditionsencountered were not unusual and thetransformer had been properly secured.The evidence accepted by the court wasthat the joints of the transformer beganworking loose when subjected to stressesand strains of the kind that could beexpected to be encountered in the courseof carriage.Moore-Bick J pointed out that under an‘all risks’ policy, there are neverthelesslimits. Insurers accept the risk, but not thecertainty, of loss. A cargo that cannotwithstand prolonged exposure toconditions of that kind cannot be regardedas fit for the voyage. Damages caused bythe nature of the goods themselves ratherthan by an external cause would falloutside the remit of such a policy. Theinsurers were able to avoid payment underthe policy.The ‘CMA DJAKARTA’ – CMA CGM S.A.-v- Classica Shipping Co Ltd, Court of Appeal[2004]EWCA Civ 114A charterer cannot limit his liability inrespect of damage to shipA fire and explosion occurred onboard theCMA Djakarta in 1999 whilst she was ontime charter to CMA CGM for trading inCMA CGM’s liner service. The incident wasattributed to two containers filled withbleaching powder. The charterpartyprovided that the vessel was to beemployed in carrying lawful containerisedmerchandise “excluding any goods of adangerous, flammable or corrosivenature”.In the arbitration that followed, thearbitrators found the charterer in breachof the ‘dangerous cargo’ clause andupheld the owner’s claim for damages inthe sum of US$26.6m for repairs includingsalvage and owners’ demand to beindemnified in respect of all cargo claimsand general average contributions.The arbitrators ruled, following thedecision of Thomas J in the Aegean Sea[1998] that the charterer could not limit hisliability under the 1976 Conventionbecause his acts or omissions in relation tothe shipment of the cargo were acts oromissions done in his capacity as charterer,not as shipowner. The arbitrators’ decisionwas upheld by Steel J on appeal to theCommercial Court.The Court of Appeal has nowoverturned this decision. Longmore LJ whogave the leading judgment, said that hebelieved Steel J and Thomas J had both“started from the wrong point”. Inreaching their decision that the charterermust be acting “as an owner” before he isentitled to limit his liability, both judgesappeared to have relied to some extent onthe history of the United Kingdomlegislation and its incremental approach tocontinued over19

case summaries continuedthe widening of the category of personsentitled to limit their liability. Thisinterpretation was also putting a gloss onthe word ‘charterer’ which was notapparent from the words used. He citedthe dicta of Lord Macmillan in a case onthe interpretation of the Hague Rules:“The interpretation of internationalconventions must not be controlled bydomestic principles but by reference tobroad and generally acceptableprinciples of construction. The duty ofa court is to ascertain the ordinarymeaning of the words used, not justin their context but also in the lightof the evident object and purposeof the convention”.Longmore LJ then looked at Article 1 ofthe 1976 Limitation Convention and saidthat two matters were immediatelynoticeable. First, two classes of people areaccorded the right to limit, shipowners andsalvors; secondly, the word ‘shipowner’ isdefined and is said to mean ‘the owner,charterer, manager or operator of aseagoing ship’. The mere fact that‘charterer’ is part of the definition of theword ‘shipowner’ cannot of itself mean thata charterer (an expression otherwiseunqualified) has to be acting as if he were ashipowner before he can limit his liability.Longmore LJ then went on to look atwhether a claim for loss or damage to thevessel by reference to which a chartererseeks to limit his liability is a claim which fallswithin art. 2.1(a), i.e was it contemplated inthe 1976 Convention that the tonnage ofthat vessel could be used to calculate thecharterer’s limitation. He concluded that theanswer was no. On the facts, the only headof claim in respect of which the charterercould limit his liability was the indemnity forcargo claims. His conclusion was thatlimitation was available to a charterer quacharterer but damage to the ship itself wasexcluded from the scope of claims subject tolimitation. A charterer’s ability to limit willtherefore depend on the type of claim thatis brought against him rather than thecapacity in which he was acting when hisliability was incurred.Leave to appeal to the House of Lordswas refused.Dairy Containers Ltd -v- Tasman Orient Line CV[2004] <strong>UK</strong>PC 22 - Privy Council (NZ case)Construction of a damage limitationclause in a contract for the carriage ofgoods by sea to see if the same isqualified by Art. 10 of the Hague Rules(‘the Gold Clause Trap’)Fifty five coils of electrolytic tin plate weredamaged by seawater. The Hague Ruleswere incorporated into the contract ofcarriage.Article IX Hague Rules; “The monetaryunits mentioned in this convention are tobe taken to be gold value.”Clause 6(B)(b)(i) of the B/L: By the[Hague Rules] , “… if the loss or damage isproved to have occurred at sea or oninland waterways; for the purpose of thissub-paragraph the limitation of liabilityunder the Hague Rules shall be deemed tobe £100 Sterling, lawful money of theUnited Kingdom per package or unit …”The loss was calculated atNZ$ 613,667.25 and Dairy Containers, theB/L holder, were awarded this sum by thefirst instance judge in NZ. The carrierhowever contended that the deemingprovision in Clause 6(B)(b)(i) applied andthat he was entitled to limit his liability to£100 Sterling, lawful money of the UnitedKingdom per damaged coil, making a totalliability of £5,500. This was upheld by theCourt of Appeal. This case came beforethe Privy Council by way of DairyContainers’ appeal against the Court ofAppeal’s decision. Dairy Containers arguedthat the limitation figure of £100 had to beinterpreted by reference to Article IX, the‘Gold Clause’.The Privy Council accepted that theeffect of Art. IX was that the figurereferred to in Art. IV (5) (the originallimitation provision) was the gold value, notthe paper value, of pounds sterling (theRosa S [1988] 2 LLR 574).Had the Hague Rules been incorporatedcompulsorily, the deeming provision wouldhave fallen foul of Article III (8) (provisionmaking null and void any attempt to lessenliability as provided by the Rules). On thefacts, the carriage was not governed byany international convention or by the lawsof Korea and New Zealand and theapplication of the Rules by contractualincorporation and the deeming provision inClause 6(B) was therefore valid.Lord Bingham, delivering the judgment,said: “The general rule should be appliedthat if a party, otherwise liable, is toexclude or limit his liability or to rely on anexemption, he must do so in clear words. Aterm in the bill cannot be repugnant to anyprovision of the Hague Rules if the term inquestion represents a modification of theHague Rules provision agreed by theparties in exercise of their freedom toagree what they will. It would similarly beabsurd to hold that a clear contractuallimitation agreed by the parties isinvalidated by article III rule 8 of the HagueRules.”The carrier’s maximum liability wastherefore £5,500 ■20

personal injuryREPUBLIC OF IRELANDPersonalinjury claims:a changinglandscapeBackgroundIn an effort to tackle the high cost ofinsurance in Ireland the Governmentrecently introduced legislation toimplement two new initiatives. They are:■■the establishment of the PersonalInjuries Assessment Board (PIAB); andthe introduction of strict newprocedures for the handling of personalinjuries litigation.Establishment of PIABKey features■The function of PIAB is to offer a speedyand cost-effective means of dealingwith personal injury claims without theinvolvement of lawyers.■ Under the scheme all personal injuryclaims must be referred to PIAB beforeproceedings may be <strong>issue</strong>d. In respect ofemployers’ liability claims, the schemebecame operational on 1 June, and,earlier than expected, was extended toinclude motor accident and publicliability claims as from 22 July 2004.■ This role of PIAB is limited to assessingclaims and issuing awards which can beaccepted or rejected by the parties.PIAB has no role in determining liabilityand will not make any findings of factrelating to fault or negligence.■ PIAB will only make an assessmentwhere the prospective defendantadmits liability. This is done on a ‘withoutprejudice’ basis and in any subsequentcourt proceedings liability can becontested.■ Where there is no admission of liabilityfor the purposes of a PIAB assessment, itwill <strong>issue</strong> a release certifi cate, which willallow the claimant to proceed to court inthe normal way.■ The notification of the claim to PIAB willstop time running under the statute oflimitations.Assessment of claimsAssessment of claims is based on writtenevidence, which is made available to bothparties. If a respondentdisputes the claimant’s medical evidence,PIAB will refer the medical evidence to anindependent expert.Each claim is assessed by a panel whichcomprises medical, financial, legal and otherexperts and is chaired by a member of PIAB.Claims are assessed by reference to aPIAB Book of Quantum, which identifies theappropriate levels of compensation payablefor different types of personal injury. This isavailable on the PIAB website atwww. piab.ieIf both parties accept PIAB’s ruling, theaward is binding. Where either or bothparties reject the assessment, the claimantmust <strong>issue</strong> proceedings within a period of sixmonths and the claim will be treated ‘asnew’ without any reference to the priorPIAB process.Operation of PIAB to-dateAt this early stage, there is no informationpublicly available regarding the number ofclaims handled or the rate of acceptance ofassessments. Its immediate impact has beenlimited by the fact that a huge number ofcourt proceedings were <strong>issue</strong>d in advance ofthe introduction of the scheme in order toavoid its application. In due course PIAB willpublish statistics on its website regarding theclaims handled and assessments accepted.A flowchart identifying the key steps inthe PIAB process is shown overleaf.continued over21

personal injury continuedCivil Liability and Courts Act2004The aim of this legislation is to speed up andstreamline personal injury litigation, todiscourage exaggerated claims and topenalise claimants who give false andmisleading evidence.Key features■■In personal injury claims each party isrequired to swear an affidavit verifyingthe allegations made in the pleadings;criminal penalties are provided for falseor misleading claims.A defendant may require the plaintiffto provide details of any previouspersonal injury claims made and anycourt awards received or settlementsreached. This novel provision is aimed atdiscouraging serial litigants.Quantum although it is not bound to introduction of new procedures andfollow its guidelines on compensation penalties under the Civil Liability and Courtslevels.Act 2004, will significantly alter the personalinjury regime in Ireland by reducing the timeImplications for insurers and shipand cost involved in processing personaloperatorsinjury claims where liability is admitted andThese two initiatives, namely theby streamlining the litigation process whereestablishment of the PIAB and thecases are contested ■PIAB – the Personal Injuries Assessment Board(adapted from PIAB’s process map on www.piab.ie)Claimant submits claim accompanied by medicalreports and PIAB’s feeIf documentation properly completed, limitation periodstops running upon acceptance of claim by PIAB➤Respondent receives copy of submission■■■■■■To reduce lengthy oral hearings, thecourt can direct that evidence be givenon affidavit; the right to cross-examineis preserved however.The Act will reduce the limitation periodfor the commencement of personalinjury actions from three to two years(effective from 31 March 2005).Plaintiffs are required to serve a noticein writing setting out the terms uponwhich they are prepared to settle aclaim. In determining costs the courtcan take the offer, and the defendant’srefusal to accept it, into account. Up tonow, the scope for making a formalsettlement offers, by means of apayment into court, has been limited todefendants.The legislation gives the court power todirect the parties to engage in amediation process and the court haspower to penalise, in costs, a party whorefuses to do so.Rules of court are to be introduced tostreamline the handling of personalinjury claims with the introduction ofcase management procedures andprovision for pre-trial hearings.In dealing with claims, the court musthave regard to the PIAB Book ofMatter isfinalised and nolitigation occurs➤➤Respondent admits liabilityRespondent denies liabilityLiability admitted on a‘without prejudice’ basis➤ ➤Compensation is assessedwith reference to the PIABBook of QuantumAssessment <strong>issue</strong>d by PIAB➤➤PIAB award is PIAB award isaccepted by rejected byboth parties both parties➤➤➤PIAB <strong>issue</strong>s a release certificate➤Claimant may initiate litigation; every personal injuriesaction will be subject to the new procedural rulesstemming from the Civil Liability and Courts Act 200422

isps summaryISPS and legalimplicationsWith the entry into force of the ISPSCode, we summarise below some of thekey requirements and legal implications.■ SOLAS was amended in December2002 to include a new Chapter XI-2addressing ship security.■ In addition, the International Ship andPort Facility Security (ISPS) Code wasadopted.■ The ISPS Code came into force on1 July 2004.Interested parties■ Passenger ships, including high-speedpassenger craft;■ Cargo ships, including high-speed craft,of 500 gross tonnage and upwards;■ Mobile offshore drilling units;■ Shore facilities serving such shipsengaged on international voyages.Summary of requirementsA Ship modificationsAs of 1 July 2004 vessels are required to:■ Fit and carry an automaticidentification system;■ Show the ship identification numberinternally and externally;■ Have a compliant ship security alertsystem.B Documentary / informationrequirements for shipsVessels are required to:■ Carry a ship security plan which hasbeen approved by, or on the behalf of,the flag state;■ Obtain and carry an international shipsecurity certificate <strong>issue</strong>d or authorisedby the flag state;■ Carry a continuous synopsis record<strong>issue</strong>d by the flag state;■ Carry additional information onboardrelating to parties responsible for crewappointees, parties to charterparties,and those responsible for deciding theemployment of the ship;■ Have available onboard a record ofcertain other security relatedinformation eg: the ship’s level ofsecurity in at least the last ten previousports.C Shipping company responsibilitiesAs of 1 July 2004 shipping companies arerequired to obtain an international shipsecurity certificate in respect of each shipthat they operate. In order to do so thecompany must:■ Appoint a company security officer whoshould have knowledge and training inthe relevant security matters;■ Carry out a ship security assessment;■ Designate an officer on each ship asthe ship security officer;■ Produce a ship security plan, ensuringthat the plan is approved by or on behalfof the flag state, available onboard thevessel at all times and that the measuresoutlined in the plan are implemented.■ Ensure that appropriate security drillsand exercises are carried out;■ Provide appropriate resources to theship to carry out the security plan.ISPS in practiceAs of 1 July 2004, Regulation 9 of XI-2establishes that a contractinggovernment, will have the right toexercise various control and compliancemeasures, including:■ Port state control inspection to verifythat a valid international ship securitycertificate (or interim certificate) isheld onboard;■ Inspection of the ship’s security planwith limited access allowed to specificsections of the plan relating to the noncompliance,subject to the consent ofeither the flag state or the master;■ If there are ‘clear grounds’ then theport can impose ‘additional controlmeasures’.Clear groundsThese may include evidence or reliableinformation that:■ The vessel does not correspond withthe requirements;■ Documentation is not valid or hasexpired;■ The master or ship’s personnel are notfamiliar with the security procedures;■ The vessel has embarked persons, orloaded stores in violation of the ISPSCode;■ The vessel has not completed adeclaration of security.Additional control measuresThese may include:■ A more extensive inspection of the ship;■ Delaying or deviating the ship;■ Detention of the ship;■ Restriction of operations within theport;■ Refusal of port entry/expulsion of thevessel from the port.Denied entry/expulsion■ When this occurs, the port state shouldcontinued over23

isps summary continuedadvise the appropriate facts to theport state authorities of the nextappropriate ports of call, if known, andany other appropriate coastal states;■ Such notifications should remainconfidential;■ This can be imposed where theinspecting officers of the contractinggovernment have ‘clear grounds’ tobelieve that the ship poses animmediate threat to security;■ It can only be imposed while the noncompliancegiving rise to such actionremains in force;■ If a ship is unduly detained or delayedor expelled it shall be entitled tocompensation for any loss or damagesuffered;■ Necessary access to the ship shall notbe prevented for emergency orhumanitarian reasons and for securitypurposes.Legal implicationsPaper trail: ISPS requires moreprocedures, certifications, drills etc.most of which will be the responsibilityof owners. As noted above, ISPS allowsconsiderable scope for intervention bylocal port state authorities.miscellaneousGood Practiceposters 3The Club has just published the third set ofits highly-acclaimed Good Practice posters.If you wish to receive further copies,contact the Loss Prevention Department ■Charterparties: Owners and charterersmay seek to incorporate protectiveclauses into their charterparties andcontracts of carriage dealing withliability as a consequence of noncompliancewith the ISPS Code. Usefulguidelines have been provided byBIMCO see the BIMCO ISPS Clause forTime Charterparties and the BIMCOISPS Clause for Voyage Charterparties.In the absence of any contractualwording the position will be uncertain.Insurance cover: The ISPS Code formspart of the vessel’s flag staterequirements. Non-compliance withthe ISPS Code on the part of ownersmay therefore amount to a breach ofthe insurance terms. ISM compliance isbuilt into the International Hull Clauses2002 and may be found added as aterm of other hull policies. In the eventof a vessel being found non-compliantand being denied entry or expelledfrom a particular port, this could alsogive rise to deviation which may needto be insured separately.Cargo claims: detention of the vessel, ordelays arising in connection with noncompliancewith the ISPS Code maygive rise to cargo claims for delay, lossof profit, or physical loss of perishablegoods.ConclusionOwners are faced with a host ofadditional requirements and legalimplications. In order to avoid delay ordetention of their vessels, owners willhave to continue to ensure goodcommunication and a high degreeof vigilance to ensure that wherever theirvessels trade they are going to complywith the applicable security measures forindividual ports ■........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................AcknowledgementsCarriage of coal – Cliff Mullins, MintonTreharne & Davies Ltd, Cardiff, WalesBagged rice – Dias & Co Ltd, Odessa,UkraineStowaway regulations, Singapore – SpicaServices Pte Ltd, SingaporeDisembarking stowaways, Kenya – MitchellCotts P&I Ltd, Mombasa , KenyaStowaways: ISPS Code, South Africa – RonEvans, P&I Associates, Durban, South AfricaSulphur in marine fuels – Ian Green,Casebourne Leach & Co, London, EnglandCrew clearance, Australia – Middletons, (lawoffice), Melbourne, AustraliaAccident & damage claims, Panama – DeCastro Robles (law office), PanamaCompulsory P&I, Australia – Middletons,(law office), Melbourne, AustraliaPersonal injury, Republic of Ireland –McCannFitzerald, (solicitors), Dublin,Republic of IrelandISPS summary – Matt Illingworth, solicitor,Ince & Co (law firm), London, EnglandWhilst the information given in this newsletter is believedto be correct, the publishers do not guarantee itscompleteness or accuracy.<strong>UK</strong> P&I CLUBLoss Prevention <strong>News</strong>Editor: Peter Jackson, <strong>Area</strong> DirectorEditorial assistant: Jacqueline TanTel: +44 (0)20 7204 2548Fax: +44 (0)20 7204 2106e-mail: peter.jackson@thomasmiller.comPublished by:Thomas Miller & Co LtdInternational House, 26 Creechurch LaneLondon EC3A 5BATel: +44 (0)20 7283 4646Fax: +44 (0)20 7282 5614http://www.ukpandi.comFor and on behalf of the Managers ofThe United Kingdom Mutual Steam ShipAssurance Association (Bermuda) LimitedThe United Kingdom Freight Demurrage andDefence Association LimitedLoss Prevention <strong>News</strong> on-lineThis newsletter and earlier editionscan be viewed on the Club’s website:http://www.ukpandi.com24