Assamese Folklore - Wiki - National Folklore Support Centre

Assamese Folklore - Wiki - National Folklore Support Centre Assamese Folklore - Wiki - National Folklore Support Centre

- Page 6: 6was nourished by Dr. Barua till hi

- Page 9 and 10: 9~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~The t

- Page 12 and 13: 12cut Sati’s body into pieces tha

- Page 14 and 15: 14~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Lif

- Page 16 and 17: 16~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

- Page 18 and 19: 18know the truth from her daughter

- Page 20 and 21: 20~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Physical

- Page 22 and 23: 22dance enhance the text they accom

- Page 24: ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Indian

6was nourished by Dr. Barua till his death. After him theresponsibilities were shouldered by his disciple Prof.Praphulladatta Goswamiwho could offer efficientleadership to the study offolklore applying modernscientific methodologyand theory. In 1972, thisdepartment became afull-fledged academicdepartment of GuwahatiUniversity and wasrenamed the Departmentof <strong>Folklore</strong> Research. Animportant part of BirinchiKumar Barua’s visionwas realized.Birinchi Kumar BaruaA creative writer of repute,two of his novels Jivanar Batat (On the Road Called Life,1944) and Seuji Patar Kahini (The Story of Green Leaves,1959) achieved both critical and popular acclaim. Hiscreative writings are infused with the folklore of Assam,and his engagement with it produced the pioneeringAsamar Lokasamskriti (<strong>Folklore</strong> of Assam) in 1961. It wasthe first ever comprehensive survey of folklore materialof the state written in <strong>Assamese</strong> and it fetched him theSahitya Akademi Award posthumously in 1964. He hasto his credit books on the history and development of<strong>Assamese</strong> language and literature as well as biographicalaccounts of Sankardeva. Some of his famous works are<strong>Assamese</strong> Literature (1941), Asamiya Bhasa (1949), Studiesin Early <strong>Assamese</strong> Literature (1953), Asamiya Bhasa aruSamskriti (1957), Sankardeva, The Vaisnava Saint of Assam(1960), and History of <strong>Assamese</strong> Literature (1964). In 1951,Birinchi Kumar Barua published his magnum opus ACultural History of Assam, Volume I.The Girl in the Rock: A Telangana Taleand Vasistha’s Retelling—KATIKANENI VIMALA & DAVID SHULMANMake That Sesame on Rice, Please!Appetites of the Dead in Hinduism—DAVID M. KNIPEAmerican Public <strong>Folklore</strong> – History, Issues,Challenges—ROBERT BARONThe Rajasthani Epic of PĀBŪJĪ - A PreliminaryEthnopoetic Analysis—HEDA JASONChildren’s oral literature as cultural story-tellersand relation with modern mass media in India—LOPAMUDRA MAITRAProf. Barua died at the age of 56 on March 30, 1964,after a brief illness. Within the short span of his life,he left behind a legacy of scholarship of the highestorder in varied fields like <strong>Folklore</strong>, History, Literature,Language, Art and Culture, and Sankardeva Study.One would like to conclude with the obituary forProf. Birinchi Kumar Barua by the famous AmericanFolklorist Dr Richard M. Dorson:“In the spring semester of 1963 Professor Barualectured on ‘The <strong>Folklore</strong> of India’ as visitingprofessor of <strong>Folklore</strong> at Indiana University…Wenegotiated a contract for two volumes he would editon Folktales of India to appear in the Folktales of theWorld series. He had other ambitious projects: for anEncyclopedia of Indian <strong>Folklore</strong>, for a book surveyingthe Folk Traditions of India. To us Prof. Barua appearedimposing, handsome, sturdy, and in continual goodspirits. He organized his lectures, the first on theirsubject in the United States, with logic and clarity,and delivered with feeling. All his listeners receivedthe impression that Indian civilization was permeatedwith a folk culture, and that her classics dipped deeplyinto the wells of folk tradition. ‘In India a child singsbefore he talks, and dances before he walks’ he saidmemorably…Professor Barua became our cherishedfriend. His sudden death is a heavy blow to hisAmerican as well as his Indian colleagues, and to thecause of international folklore scholarship (Dorson1994:20-21).”ReferenceDorson, R.M. (1994) ‘Birinchi Kumar Barua’, Bulletin ofthe Department of <strong>Folklore</strong> Research No. 2, Guwahati:Guwahati University. ❆ifrj Indian <strong>Folklore</strong> Research JournalVolume Eight, December 2008Table of Contents:t Collective Memory and Reconstruction ofHo History—Asoka Kumar SenPhoto essay on Serpent God WorshipRitual in Kerala—SURESH KUMARSUBSCRIPTION:INDIA:Rs.150 for single issue (Rs.1200 for 8 issues)OTHER COUNTRIES:$10 for single issue ($80 for 8 issues)To get our publications send DD / IMO drawnin favour of <strong>National</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Support</strong> <strong>Centre</strong>,payable at Chennai (India)INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

8However, the same name is used by the Dimasas torefer to the <strong>Assamese</strong>. This terminological dissonanceneeds a little explanation as both the Ahoms and the<strong>Assamese</strong> are actually two different categories. TheAhom is an ethnic group that migrated to Assam in theearly thirteenth century, whose six hundred years ofrule was instrumental in the formation of geographicalcategory called Assam, while the <strong>Assamese</strong>, usuallymeant to denote people living in Assam, is rathera complex and politically loaded term. The nonrecognitionof differences between these two categoriesof people derives from its folk perception which maybe explained in terms various changes the regionunderwent in the medieval times.The term Asimsa was originally used for the Ahoms.It is to be noted here that most Dimasa words arederivatives. They called the Ahoms so because theywere known to have migrated from Siam or Shyam bythe Dimasas. The term Asimsa is changed version ofHa-shyam-sa meaning son of land of shyam. (the suffixsa is used by Dimasa to denote any community, i.e.ha-di-sa, Bengalis as son of wet paddy field, gufu-sa,the white man (son) or European). The Dimasas termof Asimsa referring to the Ahoms extended to the othergroups living in the land of Ahoms. Interestingly, theyshare close emotional bond to their agnates living inthe land of Ahoms and refrain from designating themas Asimsa. Many scholars believe that the term Assamfinds origin in this word ha-shyam-sa or Asimsa.It would be convenient to draw the conclusion thatthe type of songs discussed in this essay forms a partof peoples’ memory. Their performances are actuallyrecounting of events in the past which shaped thecommunity’s destiny. Every act of performing this act ofretelling is similar to rereading past history, though theact of reading itself cannot be put beyond context. Thecontext of reading is crucial in shaping contemporarypublic perception over issues and events, especiallyamongst people ‘without history.’The Song (translated by the author):O’ Lord Almighty of my artless grandfather/ Ibow to you in the eastO’ Goddess Almighty of my innocent/guilelessgrandmother/ I bow to you in the westLend your ears o’ my elderly folks/ Lend yourears o’ my brothers and sistersCotton weaved cloth by itself / In our land ricegrew by itselfGold decked the swaying hands/ Silver clad thewaving hands.These days, we are forced to be <strong>Assamese</strong>neighboursThese nights, we are forced to be fishermen’sfriendsThe <strong>Assamese</strong> continues to push our boundaries/The fishermen continue to fish our watersThe <strong>Assamese</strong> is asking for Land/ Measuring theblade of a straw/thatchThe fisherman is asking for water/ Measuring athrottleThe <strong>Assamese</strong> are foresighted in thoughts/ Thefishermen are deft diplomatsLend your ears o’ my brothers and sisters/ Do notsleep away the hoursDo not idle away the times/ Wake up o’ fellowbrothers and sistersArise o’ fellow elderly folksLest you wake up/ Paternal skill will be lostLest you arise/ Maternal skill will be lostIn grand old book thou shall find the paternalskillCrafted in designs of hand fans belong thematernal skillDo not learn the way <strong>Assamese</strong> eat/ Do not learnthe way Fisherman dressWill eat the fathers’ way/ Will dress the mothers’wayIf paternal working skill not abandoned/ Goldendays would returnIf maternal weaving skill not abandoned/ Silverynights would returnAgain gold shall deck the swaying handsOnce more shall sway silver clad handsJudi shall flow in torrents/ Khaji shall formhillocksFawn shall fickle around six hills/ When gold shalldeck the swaying handsShall consume fruits of six banyansDance till headgear falls/ Sway hands till rikhaosaslips.Judi—shortened from of Judima, meaning Dimasatraditional rice beer.Khaji—meat or vegetables served with rice beer orany other form of drink.Rikhaosa—a piece of cloth worn like stole or chadorby women.ReferencesBaruah, Nagendranath( 1982) Dimasa Sokolor Geet-Mat,Guwahati: Assam Publication BoardReddy, Y A Sudhakar & Durga , P S Kanaka (2008)Indian Folklife, Serial No.29, Chennai: NFSC.❆INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

9~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~The trickster in <strong>Assamese</strong> Folktales~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ANIL BOROLecturer, Department of <strong>Folklore</strong> Research,Guwahati University, Guwahati.The trickster figure in folk narratives all over theworld is a tricky, skillful and resourceful character,often full of contradictions and ambivalence.A rogue and a clever deceiver, he can outwit and outplayhis adversaries by virtue of his wit and presenceof mind. The tricksters of <strong>Assamese</strong> folktales, unlikethe trickster of, say, Native American tales and myths,isn’t a culture hero. The <strong>Assamese</strong> trickster is notresponsible for creating conditions that allow for thecivilization of human society.The <strong>Assamese</strong> word for trickster is Tenton or Teton,literally meaning “the clever one.” In his pioneeringwork on the tales of Assam, Praphulladatta Goswami hasincluded four trickster tales along with other versionsand parallels amongst other ethnic communities of theregion and other central Indian tribes.The trickster is very often out of his home for hisapparent foolhardiness. This feature is seen in many ofthe trickster figures of this region. In one such tale, hemeets some thieves who ask him to enter a house andthrow out the valuables to them. He beats on a druminstead and the householder gets up and apprehendshim as the others flee. As he is being taken to court,he finds a man cry out at an unruly bullock, “Wouldsomeone kill it with but one stroke?” Tenton deals theanimal a fatal blow and sends it to its death. So theman follows him to court. As they go on, a woman isseen selling bananas to the following strain,Give me a paiseTake a bunch,Then go away, a kick on my breast.Tenton drops a paise, takes a bunch of bananas andgives her a kick. She also follows him to court. At thecourt he explains his action thus: “Does a thief beaton a drum in the home he has entered? I but lookedfor something to eat.” The King’s minister observeshere: “His words are worth a hundred rupees”. Hegoes on, “I did what that man had asked me to do:I slew the bullock with but one stroke”. The ministeragain observed that “His words are worth a thousandrupees”. He concludes by declaring: “I paid exactlywhat the woman had asked for her bananas”. Theminister reiterated that “His words are worth a lakhof rupees”.The King acquits Tenton. After a few days Tenton comesto the court and claims a hundred and a thousand anda lakh rupees from the minister, for as he declared, “Aword is a word”. The king forces the minister to makegood the claims. With the money, the lad persuadesthe minister’s daughter Champa to bathe and feed him.He leaves his money with Champa and asks the King:“Who bathes whom? Who places a seat for whom? Whofeeds whom with her own hands?” The King answers:“Why a wife does these things for her husband”. Thenthe lad Tenton tells the King that Champa has donethese things for him. Despite the opposition of the irateminister, the King allows the lad to marry Champaand makes him an officer [Goswami: 1970]. Thus thetrickster gains in two ways. He marries the minister’sdaughter and becomes the minister of the King. In theinitial stage of the narrative he appears not to be veryclever, but the way he responds subsequently establishhim as a trickster.In another Trickster tale entitled “Tenton”, the tricksterhero follows the same initial move. He is taken to taskby his father and is turned out of home for no faultof his own. His father wanted the son to extort somemore money from the moneylender who came in hisabsence. Out of home, the lad finds a man ploughingthe paddy field under the midday sun. He showssympathy for the ploughman for his hard work withold bullocks. The man tells that he has laid by a scoreof rupees for a new bullock. The lad feints thirst andtries to scoop some water from the muddy field. Theman sends him to his house nearby. Tenton goes andasks the man’s wife to hand over the score of rupees asher husband has secured a new bullock. The womanis suspicious and he calls out to the ploughman, “Shewon’t give”. The ploughman shouts back: “Hei! Whydon’t you give?”, thinking that she is denying thethirsty lad water. The woman hands over the moneyand Tenton makes good his escape. He buys a goatand stays the night at a stranger’s. The host offers himclothes for it is winter. He says that the goat will eat upthe cold and he does not require any cloth. He sleepson some hay and from time to time calls out: “Goat,eat up the cold.” Next morning the host exchanges thegoat for a horse. Tenton rides away. He sees a boy ata sweetshop, tells him that his name is Fly and startseating the sweets. The boy shouts to his father whois inside: “Father, Fly is eating the sweets.” “Oh, letit.” says the father. So Tenton eats as much as he can.From there he reaches a rich man’s house at evening.He halts there. Next morning he stirs up the dung ofhis horse. His kind host says, “You need not throw itaway, my son will do that”. Tenton says that he onlylooking for coins for the horse excretes rupees and hepicked up a few coins. The host buys the horse at ahigh price. Tenton returns home with all the moneyand his father takes him back. The clever youngerINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

10brother deceiving his foolish elder brother is the themeof the trickster tale entitled “Ajala and Tenton”.There are parallels of these narratives among the ethniccommunities of the region and the State. The motif ofrobbing the ploughman is found in the Mising Trickstertale. Besides the ethnic communities of Assam like theBodos, Karbis, Misings, the ethnic communities ofNagaland, Mizoram and Meghalaya have their tricksterfigures akin to the <strong>Assamese</strong> trickster figure. In taleslike this, the foolish elder brother comes to his sensesunder the influence of his neighbours and showsmaturity and outwits his clever younger brother. Thetale has an exact parallel, as Goswami explained, amongthe Meches [Bodos] of western Assam and the Meiteisof Manipur. Even the Chinese have a trickster tale withthe same motif. But in the Chinese version the elderbrother is cleverer than the younger brother.The trickster tale is very popular amongst both theliterate and non-literate society. The clever tricks of thehero provide entertainment to the listeners.Trickster heroes like the Brahmin’s servant are wellknown for their witty tricks and tirades against highcaste people. In <strong>Assamese</strong> society, casteism was neveras prominent and cruel as in the rest of India. But thisdid not mean that casteism did not exist at all in thispart of India. A review of available literature in theearly twentieth and late nineteenth century revealsthis. It is probably for this reason that the so-calledtribal and low caste people cut jokes at the expenseof the high caste people, if not in real life, in popularfolktales which have the function of “role reversal” aswell as “escape mechanism”.ReferencesAnderson ,J.D (1885) Kachari Folktales and Rhymes,Shillong.Basom,W.R. (1981) Contributions to Folkloristics,MeerutBejboroa L. (1911) Burhi Air sadhuBoas, Franz (1898) J Tait ed., Traditions of theThompson river Indians of British Columbia, NewYork: Haughton MifflinCarroll, M.P. (1984) ‘The Trickster as selfish buffoonand culture hero’, Ethos, vol 12, no 2Goswami, P (1970) Ballads and Tales of Assam,Guwahati: University of Guwahati---------- (1980) Tales of Assam, Guwahati: Publicationboard of AssamHandoo, J. (1999) <strong>Folklore</strong> and Discourse Eds. J Handooand Analiina Siikala, Mysore : Zooni PublicationsKlapp, O.E. (1954) ‘The clever hero’, Journal ofAmerican <strong>Folklore</strong>, 67.[163]Rickett, M.L. (1966) ‘The North American IndianTrickster’, History of religions 5Thompson, S. (1977) The Folktale, Berkley: Universityof California Press.Zypes, Jack (1983) Fairytale and the art of Subversion:the Classic Genre of Children and the process ofcivilization, New York: Wilman. ❆~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Notes on <strong>Assamese</strong> Place-Lore 1~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ÜLO VALKChair, Department of Estonian and Comparative<strong>Folklore</strong>, University of Tartu, EstoniaDuring the last decades a new concept, “placelore”(Est. kohapärimus), has been added toEstonian folkloristics to denote local legends(muistend), beliefs and descriptions of customs thatare connected with places, and oral histories, memoriesand other genres concerning places and toponymes(Remmel 2001, 21). Place-lore is not a distinctive folkloregenre; it is not an analytical concept but a syntheticdevice to study various genres in their connection withenvironment. According to Mall Hiiemäe, place-lorefocuses on natural and cultural surroundings, such ashills, valleys, forests, wetlands, lakes, rivers, fields,stones, old trees, graveyards, chapels, churches andother objects. The very existence of these places inthe neighbourhood supports the tradition memory ofthe local people (Hiiemäe 2007, 364, 370), who sharetheir narratives, beliefs and customs with the youngergenerations, newcomers and visitors.Research in place-lore is among the emerging trendsin contemporary international folkloristics. CristinaBacchilega’s inspiring monograph is dedicated tothe production of legendary Hawai’i in the touristindustry and connections between local narratives andthe environment (2007). She makes a clear distinctionbetween geographical locations in the landscape andplaces. The beauty of the landscape can be admiredby outsiders, who know nothing about the places as“emotionally, narratively, and historically layeredexperience” (Bacchilega 2007, 35). Place is a locationthat evokes feelings and memories and is bound toINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

12cut Sati’s body into pieces that fell all over India.All the spots became sacred places, where thegoddess is worshipped. Sati’s private parts (yoni)fell to Nilachal hill near Guwahati, where thefamous Kamakhya temple is located.It took only a few days for me to reach Guwahati. Guidedby eminent folklorist Kishore Bhattacharjee, I went toNilachal hill to witness the place, which has been thetravel destination for thousands of pilgrims. Mythsare narratives with great power to set up rituals, makepeople act according to ancient models (like the selfimmolationof widows in order to follow Sati’s divineprecedent) or take travellers to roads to visit placestouched by the divine aura of the sacred genre of myth.The vaults and walls of the Kamakhya temple shelterone of the most important peetha – cult places of thefeminine divine power shakti. The Myth about Shiva’sdevoted wife Sati, who was cut into pieces that fellall over India, gives sacrednessto the whole subcontinent asthe story identifies earth withthe body of the goddess, whois worshipped as a living deity(Kinsley 1987, 187). Place-lorecan thus be deeply religious andmystical, like the experienceof worshipping the goddess tothe accompaniment of sacredmantras, chanted by Brahminsin a dark chamber, close to thebosom of earth, where oil lampscast shadows on the ancientsculptures and on the facesof devout pilgrims, who havecome from far away to meet thegoddess.Birendranath Datta has shownthat the goddess Kamakhyawas associated with the Hindudeities Shiva and Sati duringthe historical period when the<strong>Assamese</strong> religion and customs were blended withBrahmanic tradition, dominated by pan-Indian godsand texts in Sanskrit (1998). But Nilachal hill andits close vicinity has many other stories to offer, allconnected with local history, going back to mythicaltimes. Narakasura was a great king of Kamarupa, whoselife has been discussed in several classical texts, suchas Vishnu Purana, Mahabharata and Kalika Purana(Bhattacharjee 2006, 24-25). In January 2003 we visitedsome villages in the region of Nameri national parkand conducted interviews with local people. FarmerBenudhar Das from Potasali village told us severalstories about Narakasura’s close connection with theregion. A king dreamed of marrying the goddessKamakhya, who said that she would agree only ifNarakasura would build a stone staircase to the topof Nilachal hill in one night. Kamakhya thought thatthis task would be impossible to accomplish but shewas mistaken. Narakasura was very close to finishingthe work and Kamakhya, who wanted to avoid themarriage, got frightened. She transformed herself intoa chicken and made the sound of a cockcrow. Thismeant that the night was over and that Narakasurahad failed to finish the work. But the stone staircase isstill there on the Nilachal hill as a proof of Narakasura’spower and reminder of the ancient myth. BenudharDas also told us other narratives about local rulers,such as Banaraja or Banasura, the king of Sonitpur.Krishna’s grandson Aniruddha wanted to marryBanaraja’s daughter, but the king had refused. Asthe wedding was arranged secretly, Banaraja arrestedAniruddha and kept him in the prison at Potasali – thehome village of our storyteller. Krishna wanted to setVisiting Nameri <strong>National</strong> Park in January 2003: Gojen Naroh, Anil K. Boro, Ülo Valk, the lateDipankar Moral, Kishore Bhattacharjee, Parag Sarma and Laur Vallikivi (from right to left).his grandson free and started a war against Banaraja,defeating him. Events of this mythical war explainmany place names in the region. For example, Sonitpuris nowadays called Tejpur, meaning the city of blood(Valk 2006, 142-143). Places thus become charged withnarratives and mythical meanings that are passed onfrom one generation to the next. Kishore Bhattacharjeehas shown that the link that has been made betweenthe local kings and the kin of asuras – great demonicadversaries of the gods in Hindu mythology – alsohas a social and political implication. Through suchidentifications the local political, cultural and religiousinstitutions were incorporated into the pan-IndianBrahmanic tradition (Bhattacharjee 2006).INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

13Fieldwork in the Nameri region also opened up<strong>Assamese</strong> place-lore on a smaller scale – narrativesabout places and events that are known only to a fewpeople and will probably fall into oblivion withoutbecoming a part of the mythical history. We met GojenNaroh – a man from Mising tribe who had been workingin the nature preserve for eighteen years. He told usabout Bogijuli camp in the jungle where strange thingshappen. Sometimes the crying of a woman is heardbut nobody is seen. Gojen Naroh had never heard thewailing sound but he had heard strange noises in thebuildings, like a dragging chair, somebody pulling thecarpet or banging a door. Sometimes bamboo had beencut in the bamboo grove next to the forest. When menin the camp had gone to witness what was happening,nobody was seen. Thus, it was believed that the campwas haunted. Gojen Naroh suspected that probablysomebody had committed suicide there or wildanimals had killed somebody. Such narratives aboutsupernatural encounters have been identified as legendsin international folkloristics (see Valk 2007). In contrastto myths – grand narratives that function on the publicscale – legends often remain hidden as local narratives,spread among small groups only. Also, many beliefscirculate in tradition as pre-narrative motifs, never usedto build up finished and polished narrative plots likethose in migratory legends. But also the beliefs, fearsand expectations of people whose lives are linked withcertain localities, form an important part of place-lore.Sharing it with others means opening up the hiddenknowledge that has been accumulated by generations.As a traveller in Assam, I have often felt that certainplaces have become meaningful to me thanks to thepeople who share with me their personal memoriesand tell stories that they have heard from others.Place-lore is a synthetic concept, connecting severalgenres, such as myths, legends and beliefs, andenabling folklorists to analyse the connection betweenoral tradition and environment. Place-lore appearson different scales of narration, from the sharing ofintimate knowledge among small groups, to thepublic representation of myths in books, mass media,film and theatre. The micro-level of <strong>Assamese</strong> placelorecan be studied firstly in local stories, such as thenarratives of the haunted Bogijuli camp; secondly,other stories, such as the myths about Narakasura, arewidely known and narrated on the regional level; andthirdly, there are examples of <strong>Assamese</strong> place-lore thatbelong to the pan-Indian heritage, such as the mythabout Shiva and Sati. Connecting narratives with reallocations is much more than a storytelling strategy toconfirm the truth of the story and provide materialevidence of the narrated events. <strong>Folklore</strong> animates theenvironment of traditional communities and creates asense of belonging to certain places. Generally, one’shome and its close surroundings become charged withmemories – either personal or collective memoriesof shared folklore traditions. Just as the ability tocreate and share folklore is a distinctive quality of folkcommunities, the existence of place-lore is a specialquality of environment, inhabited by people. Withoutplace-lore man would be surrounded by an emptyphysical space of alien natural surroundings; placelorelinks generations and provides them with a sharedidentity – the narratives of belonging.ReferencesBacchilega, Cristina (2007) Tradition, Translation, andTourism, Philadelphia: University of PennsylvaniaPress.Bhattacharjee, Kishore (2006) ‘Interpreting Hindu MythsConnected with the History of Tribal Kingdoms inNorth-East India’, ISFNR Newsletter. No. 1Datta, Birendranath (1998) ed. Jawaharlal Handoo‘Changing Functions of Traditional Narrative: TheCase of North East India’, <strong>Folklore</strong> in Modern India,Mysore: The Central Institute of Indian LanguagesHiiemäe, Mall (2007) ‘Sõnajalg jaaniööl’, EestiMõttelugu 73, Tartu: IlmamaaKinsley, David (1987) Hindu Goddesses. Vision of theDivine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition,Delhi: Motilal BanarsidasRemmel, Mari-Ann (2001) ‘Eesti kohapärimusfolkloristliku uurimisainena’, Magistritöö. TartuÜlikool, Eesti ja võrdleva rahvaluule õppetoolValk, Ülo (2007) ‘Eyes of Legend: Thoughts aboutGenres of Belief’, Indian Folklife. Serial no.25.Chennai: NFSC.Endnote1This article and my field trips to Assam have been supportedby the Estonian Science Foundation (grant no. 7516) andby the European Union through the European RegionalDevelopment Fund. I also thank Daniel Allen for editing theEnglish language of this article. ❆INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

14~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Life as lore: the art and timeof Pratima Barua Pandey~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~JYOTIRMOI PRODHANIHead, Department of English,North Eastern Hill University,Tura Campus, Meghalaya.Pratima Barua Pandey (1934-2002), one of thegreatest folk artists that Assam has ever produced,is an interesting phenomenon. She not onlyhelped the revival and consolidation of a folk formfacing impending oblivion, but also became the subjectof a vibrant contemporary folklore of the times. Her lifereflects the various phases of the evolving <strong>Assamese</strong>identity, and how the folk acted as a syncretic energyin the understanding of the <strong>Assamese</strong>. Her songs,popularly called the Goalparia Loka geets, are a partof a cultural community, largely the Rajbanshis, whohave been historically dispersed around a vast territoryincluding Assam, Bengal, Bihar, Southern Nepal andeven Bangladesh. When Pratima Barua picked up thesongs, they were seemingly in their last phase of life inpublic memory, for the history of the land took a sharpturn forcing the communities living in the peripheryto abandon their cultural moorings and acquire newidentities to conform to the altered geo-political legacyof the colonial times.Expeditions with her father, Prakritish Barua, in thejungles to catch elephants brought her into closecontact with the intimate rhythms of the folk. She hadthe freedom to move about the jungle, go for gameherself at times and listen to the carefree songs andstories of the campers comprising the mahouts, thephandis, and the b orkondaj. They would sing for thewhole night the songs of the elephants, the mahouts,their women back home, the women they would comeacross in the solitude of the jungles and songs of theirpain and pathos.It was also the time when the speakers of Rajbanshis,the major language group speaking the languageof these songs, had taken the political strategy ofaccepting mainstream <strong>Assamese</strong> language as theirmother tongue in Assam. Similarly the Rajbanshis ofCoochbehar in West Bengal acquired the dominantBengali identity thereby relegating their own languageto a sub-dialect. As a result, their traditional folk songsalso receded from the public sphere into little- knownprivate domains.Pratima Barua’s rendition of folk songs not only reviveda folk form but also the language of the erstwhileGoalpara district of Assam, presently comprising the fourdistricts of west Assam, namely Goalpara, Bongaigaon,Kokrajhar and Dhubri. Dr. Bhupen Hazarika made themost significant contribution in bringing Pratima Baruato the fore as an artist of repute in Assam. During hisvisit to Gauripur in 1955, for the first time, he heardfolk songs sung by a young Pratima. He found thesongs unique and her voice exceptionally mellifluous.Dr. Bhupen Hazarika returned to Gauripur the verynext year, in 1956, with a bigger mission: to includePratima’s songs in his forthcoming <strong>Assamese</strong> film, EraBator Sur (Songs of the Abandoned Road). The twosongs included in the film, dung nori dung (a songthat was sung by phandis while catching elephants)The Jacket of a Pratima Barua Album.and O birikha simila rè (a pensive song of a woman’sunfulfilled desires), not only foregrounded a youngtalent, but also a forgotten genre and language. Inother parts of Assam, people had the misgiving thatthe culture of Goalpara was a part of Bengali culture.After having fought a prolonged battle to wrest statelanguage status for <strong>Assamese</strong> they were apprehensivethat their battle for the <strong>Assamese</strong> language and culturewould take a beating.Nevertheless, Dr. Hazarika shot the <strong>Assamese</strong> film RongSabujer Gaan based on the script by Alokesh Barua, sonof renowned film maker Pramathesh Barua of Devdasfame and scion of the royal family of Goalpara. In theLP disk of Mahut Bandhu Pratima Barua had five solonumbers and one duet with Dr. Bhupen Hazarika. TheINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

15Bhupen Hazarika and Pratima Baruasongs that had so far been referred to as desi becamefamous as Goalparia loka geets and became cult songsof the oeuvre.The next big thing to happen was the radio broadcastof Pratima Barua’s folksongs. Dr. Bhupen Hazarikatook the initiative to broadcast the songs of PratimaBarua in 1961 when they were members in theProgramme Advisory Committee of All India Radio,Guwahati. Purushottam Das, who later became aneminent cultural figureof Assam, decided torecord her songs inthe studios of All IndiaRadio, Guwahati. Forthe people of Goalpara,it was strange to hearthe voice of PratimaBarua on air singingthe songs traditionallysung by ordinaryfarmers, maishals andmahouts. The songswere not receivedeasily by sections of<strong>Assamese</strong> people thathad nurtured freneticA young Pratima Barua<strong>Assamese</strong> nationalism.They raised strongobjections against the broadcasting of Pratima Barua’ssongs, which they alleged were ‘non <strong>Assamese</strong>’ and‘Bengali’. In 1958, she made her debut on the dais ofGana Mancha, the left-leaning cultural wing, in Shillongupon the initiative of her father and Bhuban ChandraProdhani of Golakganj who were the members of theAssam state assembly in Shillong at the time. Later,she was closely associated with the IPTA. She becamealmost a regular feature at the annual conventions ofAssam Sahitya Sabha and the All Assam Students’Union who honoured her with the highest publicrespect of the organization by declaring her a legendaryfolk singer.When she was removed from the life support systemin the ICU of GNRC hospital at Guwahati on 26December, 2002, the whole of Assam deeply felt thevoid she’d left behind. Normally it takes about fivehours by road from Guwahati to Gauripur; that dayit took more than twenty hours because all along theroad, throughout the night, people were waiting,braving the incessant drizzle, to have one last glimpseof their favourite princess. At Gauripur, a sea of peopleaccompanied her hearse to the cremation ground.Apart from the members of the cultural and cinemafraternity in Assam, ordinary folk from as far as Sikkim,Jalpaiguri and Coochbehar in West Bengal, and Biharjoined the last procession of the princess of Gauripur.Pratima Barua Pandey had passed into the realm of thecontemporary folklore of Assam.The Gauripur Rajabari (Palace) wherePratima Barua was born and lived.ReferenceBhakat, D.N. et al. Eds. (2003) Satajanar Smritit PratimaBarua Pandey, Dhubri: Dhubri Sahitya Sabha.Brahmachoudhury, Suriti Sarma (2006) Ganor Pratima,Pranor Pratima. Guwahati: Bina LibraryChakraborty, Shyamal (2005) Mahut Bandhu Rè:Pratima Barua Pandeyr Jiban O Gaan. Kolkata:Gyan Bichitra Prakashani,Das, Dhiren (1994) O Mor Hay Hastir Kanya Rè,Gauripur: Dhiren Das_____ (1994) Goalparia Loka Sanskriti aru Loka Geet,Guwahati: Chandra Prakash. ❆INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

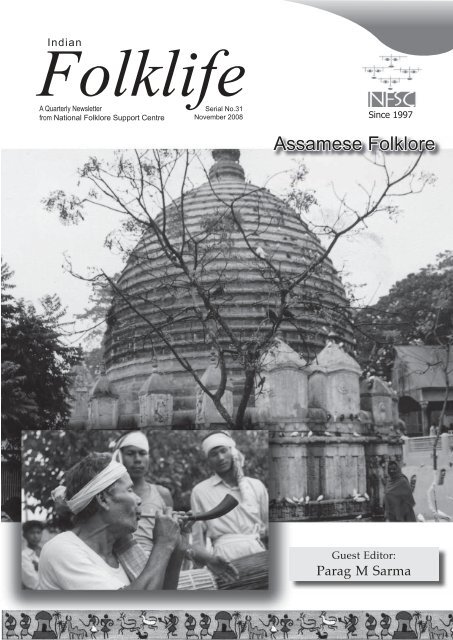

16~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Festivity, Food, and Bihu: a shortintroduction to the national festivalof Assam~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~PARAMESH DUTTAOn analysis of Bihu festivals, we can perhaps come to aLecturer, Department of Cultural l Studies,conclusion that t Bihu is an ancient folk lkfestival of fAssamTezpur Universityand its inhabitants. The Rongali Bihu is essentially aspring festival that sets the tune for the advent of aAmongst the many festivals celebrated in Assam, new agricultural cycle. It starts with the washing andthe festival of Bihu is perhaps the best known worshipping of agricultural implements, the bullocksand synonymous with its culture and people. and the cows and proceeds to the dances and songsAssam celebrates three Bihus, amongst which the Bohag of the festivities. The Bihu dance is supposed to beBihu or Rongali Bihu (celebrated in mid-April) can be related to the fecundity principle of nature, and wastermed the marker of the community’s nationality. All originally performed in the fields to symbolize thethree Bihus are associated with the agricultural cycle fertile and productive nature of the earth. With theof the region. The Rongali (<strong>Assamese</strong> for gaiety and passage of time, the Bihu assumed the role of romanticcelebration) Bihu marks the <strong>Assamese</strong> New Year and interplay between young men and women and thethe advent of the agricultural cycle. The Kati (the period accompanying songs reflected different facets of life infrom mid-October to early November) Bihu celebrated Assam. Thus the Bihu songs could include facts likethe building of new bridges, visitsof politicians, changing fashion andthe rural-urban divide.Till the fourth and fifth decades ofthe twentieth century, Bihu songsand dances survived in the ruralhinterland of Assam. It may bementioned that during turbulenthistorical times in the last part ofthe 18th and the first part of the19th century, both revolutionariesand rulers used Bihu songs as socioculturaltools to rally the people.During this period, some elite ofthe state, under the influence ofcolonial and western paradigms,disparaged the Bihu festivities aslurid, immoral and having sexualovertones. However, the Bihu hadA man blowing pepa in a performance of bihu dancealready moved away from the fieldsto the royal amphitheater, thanks to the patronage ofin the <strong>Assamese</strong> month of Kati marks the completionthe Ahom kings. Later, in the mid-twentieth century,of sowing and the transplantation of paddy. Marked bybecause of the efforts of some scholars like Lakshminathaustere celebration, it is characterized by the lighting ofBezborua, Gyanadhiram Barua, Radha Gobinda Baruahearthen lamps in the paddy fields and courtyards ofamongst others, the Rongali Bihu came to the stages ofhomes as obeisance to the almighty for good harvesturban and semi-urban locales in the state.and the protection of crops. The Magh Bihu or theBhogali (the <strong>Assamese</strong> equivalent of feasting) Bihu The Rongali and Bhogali Bihus are marked by theirmarks the end of the successful harvesting of crops and distinctive food items, where food becomes a metaphorthe ensuing celebration. The Bihu festivals are secular for success, happiness and prosperity. It is customaryand, by and large, non-religious in nature. People to eat rare varieties of pot herbs (xak in <strong>Assamese</strong>)belonging to different castes and creeds participate in during the celebration of Rongali Bihu. In the upperthe celebrations.reaches of the Brahmaputra, many people eat 101INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

17varieties of pot herbs on the first or seventh day ofthe celebration of Rongali Bihu, whereas in the lowerreaches of the Brahmaputra, people eat seven varietiesof pot herbs on the 7th day of Rongali Bihu. Differentvarieties of pancakes and confectionaries made out ofcoconut, sesame seeds, jaggery, rice powder, stickyrice, and milk products are prepared in a traditionalway. Amongst some ethnic communities, brewingof rice beer and preparation of pork and chicken is amust.The Bhogali Bihu is the Bihu given entirely to feasting. Itis a time for eating and merrymaking after a successfulharvest. Community feasts are organized across theentire state. Fish and meat are inseparable items ofsuch feasting. It is obligatory for people to visit eachother’s households as invitations are not sent out.Bihu has spawned a distinctive material culture inAssam. The mekhala chadar (two-piece apparel wornby women in Assam) woven out of the muga silk is adistinctive identity marker; so are the colourful japis(originally protective headgear woven out of bambooand palm leaves worn by farmers as protection againstsun and rain) andthe intricately wovengamochas (traditionalcotton towels for wipingthe body; ga meansbody and mocha meansto wipe). Musicalinstruments include thedhol (traditional drums),the tal (traditionalcymbals), the pepa(traditional wind pipemade out of buffalohorn) and the gagana(a delicate but simpleinstrument made out ofbamboo and played bysimultaneously blowingAssanese dhol, a traditional drumwind from the mouthand vibrating the instrument by hand). In spite oflocal variations, Bihu remains a cohesive cultural forceamongst the different communities of Assam even inthe present divisive times. ❆~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Women in <strong>Assamese</strong> Folktales~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~MANASHI BORAHUGC-Senior Research Fellow,Department of Cultural Studies,Tezpur UniversityThe <strong>Assamese</strong> equivalent for folktale is Sadhuor Sadhukatha. The word Sadhu means “therighteous”; hence Sadhukatha means a moral tale.Another meaning is derived from Saud or Saudagar, amerchant. According to P. GoswamiThe <strong>Assamese</strong> for an oral tale is sadhukatha,usually derived from the Sanskrit sadhu, amerchant, and katha, a tale, meaning therebythat the sadhukatha is a tale told by a wanderingmerchant (Goswami 1970: 80).The present discussion focuses on some of the <strong>Assamese</strong>folktale collections by Lakshminath Bezborua which fallunder Magical or Wonder or Romantic or Supernaturaltales. The Burhi Air Sadhu and the Kakadeuta aruNatilora are two famous collections by LakshminathBezborua.By analyzing the gender roles played out in these tales,an idea of the status of women is <strong>Assamese</strong> society canbe made. Outlines of the selected tales follow:The Kite’s Daughter:A baby girl was abandoned by her mother because shewas warned by her husband that he will sell her ifshe gives birth to a girl child again. A Kite broughtup the girl, and married her off to a merchant withseven other wives. The co-wives created difficulties forher and the Kite mother would help her in difficulties.Once, the girl was set to weave a cloth and cook rice.When she called her Kite mother, the latter appearedand performed everything magically. The co-wivesof the girl later killed the Kite mother and sold thedaughter to a tradesman. She was found wailing on theriverbank by her husband. The merchant commandedhis senior wives to walk on a thread stretched across apit full of spikes. Six of them fell in, while one escapedbecause she was not in the plot to sell the Kite’sdaughter (Bezborua 2005: 41-47).Tula and Teja:A man had two wives; the younger one was his favourite.The elder wife had a daughter named Teja and a sonnamed Kanai. The younger wife had a daughter namedTula. Once, the co-wives went fishing. The youngerone pushed the elder into the water, muttering: “As abig tortoise may you stay.”Later, the tortoise revealed herself to her children andgave them food every day. They became healthy andstrong. Their step mother observed this and came toINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

18know the truth from her daughter who accompaniedTeja and Kanai. The stepmother then feigned illnessand told her husband through an old lady physicianthat she will be cured if she was fed on tortoise flesh.The tortoise mother came to know this. She told herchildren that they should not eat the flesh and mustbury her legs and bone on the banks of the tank.Two trees, bearing flowers and fruits of exquisitebeauty and taste, grew at the spot. The produce of thetrees was in great demand. Kanai refused to give thefruits and flowers to the king unless he promised tomarry his sister. The king, seeing the beauty of Tejamarried her. After the marriage Teja is faced with thejealousy of the king’s elder wife. The co-wife used tocreate problems for her from the very beginning. Shewas guided by her old lady servant. But the king wasalways kind to Teja. At Teja’s happiness her stepmothergrew more jealous. One day she invited Teja to cometo her place and after a few days she pushed a thorninto her head and turned her into a myna. Her stepsister put on her dress and went to king’s home as perher mother’s advice. The myna followed her. Tula wasalmost a look-alike of Teja; so the king was unable torecognize her. The myna tried to tell him the truth oneday he overheard her and asked the bird to alight onhis shoulder. The bird flies to him and the king, findinga thorn in its head, pulled it out and Teja appeared inher real shape. Then the king killed the imposter andcut her into pieces and sent it to her scheming mother(Bezborua 2005: 48-57).Three female stereotypes are found in the above stories:(a) Young women: daughter and bride, (b) Middle-agedwomen: mother, stepmother, and co-wives and (c) Oldwomen: lady physician, lady servant etc. Young womenand old women have a comfortable position in thesociety as compared to the middle-aged women. Youngwomen are generally daughter and bride. A daughtergenerally receives love and care from parents. Similarlythe bride also enjoys a comfortable position as comparedto the middle-aged women. It is revealed in both thetales that the new bride always receives the love andcare from her husband. But it is conditional and, lateron, depends on her fertility and successful managementof household work.It is depicted in the tales that relationship between thespouses affects the relationship with their children.Generally the mother figure is portrayed as a morecaring one for the children whether it is a human beingor animal. In the first tale the Kite mother providedutmost care to her daughter. On the other hand thefather’s role towards his children often depends onhis relationship with their mother. In the second taleTula and Teja, the father was indifferent towards thewellbeing of Teja and Kanai because their mother is nothis favourite wife. He provides all care to his youngerwife and her daughter Tula.The preliminary requisite of women for marriage asdepicted in the folktales is mainly beauty. In both ofthe tales the merchant and the king agreed to marrythe Kite’s daughter and Teja by seeing their beauty.But to sustain the marriage, giving birth to a childand being expert in household work is necessary. Thewomen unable to perform household work and bearchildren are often driven out from home. In the firsttale, the merchant began to love the kite’s daughtermore because of her expertise in household work andweaving.Among the middle-aged women, the mother figureis always portrayed as a symbol of tolerance andloyalty, who wishes well for the children, whereasthe stepmother and co-wives are depicted as cruel,immoral, disobedient, disloyal and cunning persons.They create difficulties in the life of their step-childrenand co-wives. They don’t hesitate to commit heinouscrimes like killing their stepchildren and co-wives tofulfill their desires. In the first tale, the co-wife of thekite’s daughter killed her mother and sold her to atradesman. In the second tale, the younger wife killedthe elder wife and, later, even tried to kill her stepdaughterTeja.The old women are also depicted as bearers of bothnegative and positive qualities but enjoy a comfortableposition compared to young and middle-aged women.In the above tales, negative qualities find prominence. Inthe tale of Tula and Teja, the old lady helps Teja’s stepmothercatch the tortoise mother. In the same tale, theadvice of another old female servant creates difficultiesfor Teja. Other old women like grandmothers andmothers-in-law are often depicted in <strong>Assamese</strong> tales.The grandmother is always depicted as good for thegrand children. But both good and bad qualities arefound in the case of mother-in-law.It is also evident from the cited tales that polygamyand remarriage for the man are the socially acceptednorm. The woman can take care of the children alonewhen her husband dies or if she is abandoned byher husband. Men often remarry for the sake of hischildren, whether the children are happy with themarriage or not.Thus, it is seen that gender roles in <strong>Assamese</strong> folktalesare basically generated by values of patriarchy, and themorals these tales convey consolidate the patriarchalworld order. The ideal qualities of women, as depictedin folktales, are chastity, purity, obedience, loyalty andtolerance. The ideal woman is not supposed to complainagainst male authority, and about the problems sheis facing and the injustice meted out to her. Cruelty,immorality, cunning and being disloyal are some ofthe negative attributes of women depicted in <strong>Assamese</strong>folktales. Most of the positive qualities belong to themother and most negative qualities are possessed bystep-mothers and co-wives.ReferencesGoswami, P. (1970) Ballads and Tales of Assam, 2nd ed.,Guwahati: University of GuwahatiBezborua, Lakshminath (2005) Burhi Air Sadhu,Guwahati: Kitap Samalaya. ❆INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

19~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~The Co-Wife and Step-MotherMotifs in <strong>Folklore</strong>: A Case Studyof Some <strong>Assamese</strong> Proverbs~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~MANDAKINI BARUAHUGC-Junior Research Fellow,Department of Cultural Studies,Tezpur UniversityIn woman-oriented <strong>Assamese</strong> proverbs, two of themost common motifs are those of the co-wife andthe step-mother. It is interesting to note that womenare more often than not at the receiving end of suchverbal behaviour, as they are held up as either ideals tobe emulated or targeted as objects of abuse. However,in <strong>Assamese</strong> proverbs the latter is more common thanthe former. Moreover, such proverbs depict femalejealousy and hatred.‘Satinir pok diu bolotei bastu bahi hai jowa.’(If you think of giving it to the co wife’s son, thefood cannot but go stale)‘Nijar nak kati satinir jatra bhanga’(Cut one’s own nose to prevent the co-wife fromtraveling).‘Saman satinir kolat po,Ghumati nahe cakut lo’.(If the son is in the co-wife’s lap,He cannot sleep but has to cry.)However, depiction of such intense rivalry between cowivescan be seen as a subversion of the patriarchalorder and is perhaps a pointer to the promiscuousnature of man. As these proverbs are mostly presentin the repertoire of women, it can be seen as aninternalization of the patriarchal structure in order tosubvert it as it is also a kind of warning for the manwho is tempted to stray from wedlock.‘Ejoni thakile (thakunte) ejoni anile kharialsunibo lage’.(If one gets another woman in the presence of theother, get ready for a life of misery)Another common motif is that of the step-mother.Usually, in most items of folk literature, thestep-mother motif is used in such events as whenthe children have lost their own mother. The stockimage of a step-mother is of one who favours herbiological offspring and is very cruel towards stepchildren.‘Dhankherar juye mahi air marame saman’.(There is equality between the simmering huskand the step-mother’s affection)‘Mahi air marame (adare) kherar juye saman’.(There are similarities between the step-mother’slove and the burning straw)‘Ataitkai tita nemu tengar patTatokoi tita mahi air mat’.(The most bitter taste is the lemon leavesBut the step-mother’s words surpass it)Though polygamy is the enabling factor of the above<strong>Assamese</strong> proverbs, widows do not find a place in thescheme of multiple marriages. This points out to thefact that the idea of a woman marrying more than oncewas taboo.‘Su bat dur gaman tak nidiba eri,Burhi haleu jiyari aniba,Teu naniba bari.’(Do not miss out on the chance to travel the goodlong wayFor it is better to get married to an aged daughterThan to a widow.)The proverbs at one level can be an internalizationof overt patriarchal structures; at another they aresubversive in the sense that they hold out a warningfor the woman who is ready to accept a married manor a man who strays from monogamy. Polygamy maybe out, but adultery still continues.ReferencesA. Rosan , Jordan and de Caro, F.A. , (1986) “Womenand the Study of <strong>Folklore</strong>”, Signs, Vol.11, No. 3.Storm, Hiroko (1992) ‘Women in Japanese Proverbs’,Asian <strong>Folklore</strong> Studies, Vol.51, No.2Rajguru, Sarbeswar (2003) Asamiya Pravad, Guwahatiand Golaghat: Balgopal Prakashan, 2nd ed.Borooah, Sahityaratna Chandradhar Ratnakosh,Guwahati: Saraighat Prakashan,. 1st ed.Malik, Said Abdul (1988) Raijar Mukhar Mat, Guwahati:Students’ StoriesBordoloi, Dulal. (1999) Phakara Jojana, 2nd ed.,Guwahati: Lawyer’s Book Stall. ❆INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

20~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Physical Folklife of Assam~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~PARASMONI DUTTAAssistant Curator, Museum & Archive,Department of Cultural Studies, Tezpur University.Physical folklife or material culture, or what wenow call tangible heritage, can be regarded asindicative of the various facets of the culturalprocess of a community. The materials or artifacts arethe most vivid expressions of the interface of man andenvironment. They provide valuable glimpses intothe inner spheres of a cultural realm and the valuesthat accompany varied cultural manifestations, bothaesthetic and functional.Food is the most visible and frequently encounteredcultural manifestation of a community. Though notstrictly artifact in the sense that it is the most liminalof categories and continuously responds to externalrealities, food provides an idea about the values andmode of life of a community. In the case of <strong>Assamese</strong>foods, characteristic features are the limited use of spiceand the use of endemic herbs that might seem exoticto one new to the locale. Varied recipes for fish andthe widespread use of pork, chicken, lamb, mutton,duck, and pigeon characterize the local cuisine. Theapparent simplicity of the cooking process, whichmostly involves boiling, cloaks the widespread useof local ingredients like pot herbs and bamboo shootsthat gives the food distinctive taste and aroma. Use ofmediums like vegetable oil and mustard oil are basicallycolonial inputs arising out of contact with peoplefrom outside the region. The most unique <strong>Assamese</strong>preparation is Khar, an alkaline preparation derivedfrom the burning of dried banana leaves and plant, andusing the ash as a medium to filter water through. Kharhas become a definite marker of <strong>Assamese</strong> identity, ashas the chewing of raw areca nut. Several varieties ofrice beer add punch to celebrations all over the state,except amongst the caste Hindus for whom it is not atraditional food item.Assam is perhaps the most famous for her indigenoustextiles woven out of local varieties of silk and cottonthread. <strong>Assamese</strong> textile “surpasses others in the mattersof colour, design and craftsmanship” (Datta et al 1994:215). Weaving is considered an essential skill for womenin rural and semi-urban <strong>Assamese</strong> households, andthe loom is an indispensable part of their life. Weavingin Assam is not a caste-based profession. Differentvarieties of silk threads like muga, eri and pat areextracted through elaborate indigenous methods fromdifferent varieties of silk worms. The sense of being<strong>Assamese</strong> is almost synonymous with the gamocha,(literally meaning a towel but multi-functional inpractice, an item held in high esteem and an importantmarker of cultural identity) The <strong>Assamese</strong> gamochais mostly woven out of white threads with colourfuland intricate inlays in red. There are different varietiesof gamocha woven for religious and auspiciousoccasions.Wood carving is an important traditional craft of Assam.Exquisite wood carvings can be seen in the furniture,doors, walls, beams, decorative panels and ceilings inhouses. Khanikars of the satras (vaisnavite monasteries)are versatile artistes, equally skillful in painting,architecture, manuscript-making, mask-making andwood carving. The finely sculpted images of garudaand other celestial characters, various decorated traysand pedestals for keeping holy books bear testimony tothe rich tradition of satriya woodcarving. Manuscriptmaking, both with and without accompanying paintedillustrations, on barks of agar trees and cotton folios,is another distinctive tradition of graphic art in Assam.Mask-making in Assam is primarily related to thebhoana – a vaisnavite theatrical performance. Clay orpapier-mâché is applied over structures of bambooand wood to make such masks which are painted withlocally-made colours.Bamboo and cane products of Assam, in the formof furniture and other domestic implements anddecorative objects are of acclaimed quality. The japior the hat made of bamboo strips and dry palmleaves, a common trait of the south Asian region,is another eye-catching item of <strong>Assamese</strong> materialculture. Like gamocha and sorai, it has also earned thedistinction of being an icon of <strong>Assamese</strong> identity and isdisplayed as decorative item in households and officepremises.Brass and bell metal craft that produces differentutensils and decorative items is of special importance.One very important product of this craft is the sorai,a decorative platter with a detachable cover at the top.Seen in various sizes, it is a valued and revered item,and like the gamocha, a marker of <strong>Assamese</strong> identityin contemporary times. There are also the traditional<strong>Assamese</strong> jewellery made of gold, silver and copper,in distinctive local motifs and styles.Various domestic implements, pitchers, clay-lights,idols and toys of terracotta are found in the Goalparaand Kamrup regions of the state. Folk toys are alsomade from pith in GoalparaINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

21Assam and the other states of North-East India aregeographically located between the Indian subcontinentand Southeast Asia. The physical folklife of the regionprovide ample evidences of cultural fusion: if onefinds the sorai and the japi to be of Southeast Asianorigin, the terracotta toys of Assam are unmistakablyHarappan in make and style.ReferencesDatta, Birendranath et al (1994) A Handbook of <strong>Folklore</strong>Materials of North-East India Guwahati: ABILAC.Prown, Jules Davis (1982) ‘Mind in Matter: AnIntroduction to Material Culture Theory and Method’Winterthur Portfolio Vol. 17, No.1. ❆~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Folk dances of Assam: a short appraisal~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~MADHURIMA GOSWAMILecturer (Senior Scale),Department of Cultural Studies,Tezpur UniversityThe folk traditions of Assam encompass a greatvariety of occasions and events to celebrate.Farmers and agricultural workers have a danceto welcome practically every seasonal change. Theydance with joyous abandon to create for themselvestheir raison d’ etre - a reinstatement of beliefs rooted inthe mythology of their land and culture. Originatingin the harvest festivals of our ancient ancestors, whenthe gods were invoked or appeased through magicalverses and dancing feet, the folk dances retain much ofthe spontaneity and vitality of their primary impulse.In earlier times, man supposedly bridged his world andthe one beyond through dance, assuming the role ofgods and demons; even today, the dancing steps taketheir cue from nature, which at times is conquered,and at others, befriended. There is an essential rhythmthat binds the dancer and the environment into anorganic whole; and this is reflected in the varied beatsand movements of the folk dancers.The folk traditions of Assam too, encompass a greatvariety of occasions and events to celebrate. Peopleconsider it as art, work, ritual, ceremony, entertainment,or any combination of these, depending on the cultureor society that produces it.There are dances that celebrate the bounty of MotherNature and celebrate the generous gifts showered byher. Bihu is performed by young men and womenreflecting youthful passion and joy of life. Thedance movements are patterned in a way that can beintelligible to the audience. The slinging of the hands,and vigorous body (hip) movements symbolize mirthand yearning for union. The moving body here is amechanism by which meaning is produced. A preludeto the Bihu, the husori, is a slow dance, the text sungand danced by clapping of hands to keep the rhythmof the performers, as they make circular patterns thatare repeated till the end of the singing. The dancersmove freely in simple movements and make allowancesin the choreography for others to join in and expresstheir joy through individual dance movements that arecreated spontaneously. Finally the household in whosecourtyard the event takes place is blessed.The Deodhani dance is considered more of a ritual thana dance; but essentially the same movement sequencesmay be considered a secular performance if decontextualizedfrom religious moorings. The dancer,who apparently goes into a trance, uses mimeticmovements of snakes and goddess Manasa and enactsthe popular legend of Behula. The meaning of whatis being communicated can be understood if we areaware of the rules or grammar of a cultural form. TheGoalpara region in Assam has colourful dances whichcombine the dramatic with the realistic; the performersuse props such as bamboo poles, swords and masks,both at the apparent level and the symbolic. Thebamboo pole doubles up as a phallic symbol, whilethe sword is the annihilator. The mask signifies thehypocritical nature of people or the difference betweenappearance and reality.The Bodos, a major ethnic group of the state, areknown for dances like Bagarumba and Bordoisikla thatrepresent the different hues and moods of nature.The dancers mould their bodies into various posturesand images that symbolize a movement in nature or aspirit. The shamanistic dances of the Daudini (shamandancer) are visual treats of frenzied and vigorousmovements. The movement involved here is for thepantheon in the traditional dance arena (sali) of thekherai festival, which is a social and religious occasion ofgreat significance for the Bodos. The body movementscommunicate primarily to gods, priests, and believersthat the proper ritual is being celebrated or carried out.The visual spectacle produced is one of regular andrhythmic linear movements intersecting at right angles;it generates the effect of an essential maze. Around theritual structure of the Kherai, in a semi-circular pattern,the musicians play the Kham(drum), Siphung (flute) andthe Jotha (cymbals).The Gumrag dance of the Misings is associated with theAli-ai-ligang festival which depicts the various activitiesof the Misings in their daily life. The movements in thisINDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

22dance enhance the text they accompany. Repeatedlyenacting the same movement can produce differentresults. The shaping of hands which in some waymakes reference to flowers can be moved in such amanner that every change is a new metaphor. Anotherdancing event, Porag, takes place after the harvest.The neighbouring villages are invited to take part inthe celebrations which lead to dancing and beating ofdrums. Though initially the event looks competitive, itfinally ends in harmony.The Haidang songs of the Sonwal Kacharis, anotherimportant ethnic group in Assam, are performed bymales and have very interesting body movements.Most of the body movements correspond to the Ojapalidance movements, which are performed by menin lower Assam and are an important componentof many religious rituals. The bodies are swayed ingentle movements and in the Haidang, unlike the Ojapaliwhich is confined to a particular place, the dancersmoves slowly through the narrow lanes of the villages.They walk to the pace of humming bees clusteredtogether. The girls welcome them with a dance that isperformed inside a house.A very colourful festival of the Tiwa community,Sagramisawa, has some beautiful dances reflectingyouth, spirit and joy. The dance performed duringthe rice pounding activity is an exceptional creationby the people. During their leisure, womenfolkimaginatively created movements to match the rhythmof the pounding pestle. Certain ceremonies like theBarat Puja have distinctive instruments to accompanythe dances. In one such dance, an instrument made ofwood and bamboo with animal and bird motifs is usedas a clapping device. The Tiwas also have springtimecelebration (pisu) where an interesting dance isperformed. It is more fun than a structured dance. Theyoung people assemble near a muddy spot and startmaking jocular movements. Finally, people are seenholding each other and pushing them into the mud.The Deoris have significant dances of Shiva and Parvatilocally known as Gira and Girasi. These are performedinitially in the family courtyard and later are taken tothe temple courtyard where it takes a spiritual turn.The performance process is dynamic as it leads fromindividual joy to spiritualism.The Karbis have a very strong dance tradition. Mostimportant dances are performed during the Chomangkandeath ceremony. These dances have become very rareas they are performed only when there is a death in thevillage. A high spirited dance, Banjar- Kekan is dancedby boys carrying decorated bamboo poles (banjar) ina playful manner. There are other dances like Nimso-Kerung and Hachacha–Kekan which are popular amongstthe Karbis.The folk dances of Assam belong to the wholecommunity and are an expression of the creativeinterface between reality and the imaginative life. Theyreveal not only the individual talents of the people, butthe collective traditions from which they and their artform spring.ReferencesAnand, Mulk Raj (1957) The Dancing Foot, Delhi:Ministry of Information and BroadcastingDatta, Birendranath (1990) Traditional Performingarts of North-East India, Guwahati: AssamAcademy For Cultural RelationsRichmond,Farley P. (1982) Indian Theater, New Delhi:Motilal Banarsidass. ❆~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~The Folk Imagination of Bhupen Hazarika~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~NEELAKSHI GOSWAMILecturer (Selection Grade), Department of English,LOKD College, Dhekiajuli, Sonitpur,Contemporary art in Assam is a seamless interfacebetween the modern and the folk. Nowhere is it mostpronounced than in the compositions and renditions ofthe iconic Bhupen Hazarika, Assam’s face to the world.He celebrates her people, her seasons and her sightsas his songs draw their lifeblood from the villagesof Assam. Thus, in his composition for the movieAparoopa, the yearning for a time gone by is presentedin terms of the different hues of nature and a desire fora long-lost village:The folk landscape is perhaps the most enduring ofimages in Bhupen Hazarika’s songs; be it his serenadingthe evening of Shillong or celebrating life in the hillyfrontiers:(i)The Shillong eveningThe dreamy city’s endearing autumnAnd memories goldenCrossing the colourful marketsThe delicate grass caressing the bare feetBy the side of the innumerable rivuletsThe laughter and the slipThat made you and me almost fall.INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

23The evening gradually envelopsThe distant Khasi villageYou and me togetherLost to the worldTwo minds streaming togetherFlooding the tall grasses beneath the pinesAs if the flying firefliesMocks usTo be like drifting flowersOf the sweet autumn.Bhupen Hazarika’s creative imagination reaches thefurthest corners of north-eastern India and combineslandscape with folklore and culture:(ii)The Tirap frontierBeauty without compareNoctes and the WanchooTangsas and the YougliIn them I saw the furthest green horizon.Out there is the Wanchoo youthIn his hand the spear PakmooOn his neck the colourful beadsOn his head the KachanIn their loincloths dance the Showan youths.With the sweet wrappers around their delicatewaistThe rhythmic movements of the girls.The awe-inspiring mountains embraced by thekissing cloudsBehind is an indistinct sun.In the distanceI catch a glimpse of the Khoonsa hamletThe sturdy Nocte youthOn his body the traditional shirt JengsemOn his head the cane headgear seats proudlyOn his waist the colourful scabbardBusy extracting salt from rocks.The Changlang village in TirapWhere dwells the simple people LoongchangThe Tangsa farmers in the hanging bamboobridgeCrosses the Tirap River in groups.Bamboo baskets on their back.…On their way to the Margherita bazaar…Bhupen Hazarika’s composition embraced all the ethniccommunities of Assam. It could be the folk reality ofKamrup in lower Assam or the elephant catchers’ songfrom Goalpara in west Assam; the description of youthfrom different communities in their young splendouror the throbbing of the Bihu drums. Yet his songs forma picture of the composite culture of Assam.In the following song composed to the tune of Bihu,apparently by youth looking for work, BhupenHazarika annexes the whole of Assam in his celebratorymuse and presents the human face of a contemporaryproblem, unemployment, on a larger canvas. The folkprovides an outlet for the frustration of the youth:(iii)O Dear! O Dear! We have crossed theBrahmaputraO Dear! O Dear! We have crossed the DikrongO Dear! O Dear! We are rested at NaoboichaO Dear! O Dear! In quest for a jobO Dear! O Dear! We have left home and hearthO Dear! O Dear! We can’t stay at LakhimpurO Dear! O Dear! The Borali fish of TezpurO Dear! O Dear! The Kandhuli fish of LalukO Dear! O Dear! Wonder how they got mixedO Dear! O Dear! You from NegheretingO Dear! O Dear! And we from JorhatO Dear! O Dear! Wonder how we got toknow each otherO Dear! O Dear! We roamed through GuwahatiO Dear! O Dear! We roamed through DuliajanO Dear! O Dear! No job at Digboi tooO Dear! O Dear! Oil Gas CompanyO Dear! O Dear! Railway CompanyO Dear! O Dear! No sweet words there too…O Dear! O Dear! Keep wellO Dear! O Dear! Keep the pining aliveO Dear! O Dear! Till I return with a jobO Dear! O Dear! The streets of the townO Dear! O Dear! Are tread by the colourfulonesO Dear! O Dear! Yet none to beat you.Bhupen Hazarika also catches the rhythm of both thelife and music of the common folk, best exemplified byhis songs on the palanquin, the dolah, bearers.The above translations are only indicative of how Dr.Bhupen Hazarika’s creative genius draws its lifebloodfrom the folk. They hardly do justice to the full rangeof his versatility or oeuvre. However, I do hope theyconvey some of the beauty of the people and thecountryside that inspires and infuses his creativity.ReferenceDutta, D.K. (1990) Bhupen Hazarikar Git aru Jiban Rath,Kolkata: Sribhumi Publishers ❆INDIAN FOLKLIFE SERIAL NO.31 NOVEMBER 2008

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Indian Folklife Regd. No. R.N. TNENG / 2001 / 5251ISSN 0972-6470The Brahmaputra and BhupenHazarika: an enduring romance~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~PRABIN CHANDRA DASGuest FacultyDepartment of <strong>Folklore</strong> ResearchGuwahati University, GuwahatiThe Brahmaputra and Bhupen Hazarika are twoiconic identity markers of the notion of being<strong>Assamese</strong>. And the relationship between the twois the stuff of which contemporary folklore is made.Bhupen Hazarika’s composition on the Brahmaputrahas elevated it to be a part of the rhetoric of <strong>Assamese</strong>nationalism that accommodates its diverse people andculture.Mahābāhu Brahmaputra mahāmilanartirthaKata jug dhari āhise prakāshisamannayar artha(The mighty Brahmaputra, the pilgrimageof great confluenceThrough the ages it has borne the lessonof co-existence)Yet, at times, the singer’s ire is directed at the river fornot being able to inspire the people living on its banksto greater deeds and heights of achievement:Tumiye jadi Brahmāre putraSei prititva tene nām mātraNahale preranā nidiyā kiya(If you are the son of Brahma,Then it’s namesake onlyFor where is your inspiring zeal?)Again he remembers the great river as a symbol of thecourage and anger of the <strong>Assamese</strong> people:Āji Brahmaputra hal bahnimānManar digantat dhowā ureĀkāsat papiyā tarā ghurePade pade kare kāk apamān?(Today the Brahmaputra is turbulentThe minds’ horizon is clouded with smokeThe meteor roams the skyEach step holds potent indignity)If the Brahmaputra is a creator on one hand, it is alsothe destroyer in the other. It holds out a perennialthreat for the disrespectful. It is the mysterious entitythat never returns some of whom that venture intoits heart. Many Rangman, the poor working anddowntrodden class of the society, sacrifice their livesin the stream of the river when they sail to earn theirlivelihood.O parahi puwāte tulungā nāwateRangman māsalai gal……. …….. ……gadhulire parate Barhamputrar mājateRangman nāikiyā hal.… … …Hiyākhani bhukuwāi ākasale cāi cāiRahdai bāuli hal(It was the day before yesterday morningthat Rongmon went fishing in his country boatIn the Brahmaputra midstream by twilightRongmon disappearedThumping on the chest eyes heavenward boundDisconsolate Rahdai goes mad)Dr. Hazarika was born on the bank of the Brahmaputraat Sadiya. He spent a long span of his life on the bankof the river at Guwahati, Tezpur, Dhubri and manyother parts of the state. He becomes nostalgic when hesees the river from an aircraft while flying to Tezpurfrom Kolkata and wants to jump from the craft on tothe bank of the river:Akowā pakowā gāmochā ekhanJen bālit meli thowā acheSeikhān gāmochā BarhamputraSitate rod he puwāicheJen japiai bāli bhoj khāmĀjir bihu git gāmMor mon chaku porile jur(The twisting gamochaSpread out on the sand below.This gamocha is the BrahmaputraBasking in the winter sunThe desire is to jump down for a picnicAnd sing the Bihu songs.The mind and the eyes are at peace)Bhupen Hazarika perhaps also realizes that theBrahmaputra straddles numerous people and culturesand can be harnessed in strengthening the culturalmosaic of the state. Mixing the sands and water ofheritage carried by the mighty river would accommodatethe diverse reality of the state from Sadiya to Dhubri.ReferencesDutta, Arup Kumar (2001) The Brahmaputra, New Delhi:<strong>National</strong> Book TrustDutta, Dilip Kumar (1984) Bhupen Hazarikaar Git AruJibon Rath, Calcutta: Sribhumi PublishingRoy, Khiren (2008) Deoboria Khabar, GuwahatiPublished by M.D. Muthukumaraswamy for <strong>National</strong> <strong>Folklore</strong> <strong>Support</strong> <strong>Centre</strong>, #508, V Floor, Kaveri Complex, 96, Mahatma Gandhi Road,Nungambakkam, Chennai - 600 034 (India) Tel/fax: 28229192 / 42138410 and printed by M.S. Raju Seshadrinathan at Nagaraj and Company Pvt. Ltd.,Plot #156, Developed Plots Industrial Estate, Perungudi, Chennai 600 096, INDIA. Ph:+91-44-66149291/92 Editor: M.D. Muthukumaraswamy(For free private circulation only.)