War and Peace in Qajar Persia: Implications Past and ... - Oguzlar.az

War and Peace in Qajar Persia: Implications Past and ... - Oguzlar.az

War and Peace in Qajar Persia: Implications Past and ... - Oguzlar.az

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

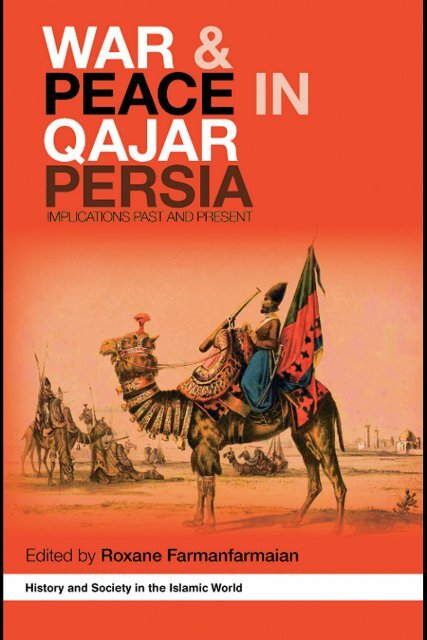

<strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Peace</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Persia</strong><strong>Persia</strong> Felix could never have been a phrase co<strong>in</strong>ed to describe modern Iran. Her lots<strong>in</strong>ce the period of the <strong>Qajar</strong>s has been to st<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the crossfire of great power politics.In this collection, a new debate takes place on the approach of the <strong>Qajar</strong> system(1796–1925) with<strong>in</strong> the context of the wars that engulfed it <strong>and</strong> the quality of thepeace that ensued. Consistent with the pattern of history, much of the material availableuntil now on the <strong>Qajar</strong> era, particularly as regards its responses to crisis, itsmilitary preparedness <strong>and</strong> the social organization of its borderl<strong>and</strong>s, was written bythe victors of the wars. This volume, <strong>in</strong> contrast, throws new light on the decisionmak<strong>in</strong>gprocesses, the restra<strong>in</strong>ts on action <strong>and</strong> the political, economic <strong>and</strong> socialexigencies at play through analysis that looks at the <strong>Persia</strong>n question from the <strong>in</strong>sidelook<strong>in</strong>g out. The results are often surpris<strong>in</strong>g, as what they reveal is a <strong>Persia</strong> moreastute politically than previous analysis has allowed, strategically more adept atspurn<strong>in</strong>g the multiple <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>trigues on all sides <strong>in</strong> the heat of the GreatGame, <strong>and</strong> shrewd at negotiat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the face of the severe economic pressures be<strong>in</strong>gbrought to bear by the Great Powers.Although history reconceived does not pa<strong>in</strong>t a purely rosy picture of the <strong>Qajar</strong>s,it does offer a reassessment based on <strong>Persia</strong>’s geopolitical position, the frequentlyunpalatable options it had to choose from, <strong>and</strong> the strategic need to protect its resources.Today, events <strong>in</strong> Iran <strong>and</strong> Western Asia appear to echo many of the power plays ofthe n<strong>in</strong>eteenth-century’s Great Game. States of the region are aga<strong>in</strong> seek<strong>in</strong>g advantageover their neighbours; the issue of oil nationalism is at the top of the agenda asit was <strong>in</strong> the early twentieth century, <strong>and</strong> great power dom<strong>in</strong>ance, <strong>in</strong>deed <strong>in</strong>tervention,has become a central theme. The essays <strong>in</strong> this volume make it clear that anunderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of how policies were formulated dur<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Qajar</strong> era can provide ahistorical dimension to current analysis of the region, as similar circumstances todaymay be engender<strong>in</strong>g like responses.This volume makes an important contribution to the effort of rewrit<strong>in</strong>g the historicalrecord. It is a revisionism that is overdue not only <strong>in</strong> respect to an era that<strong>in</strong> itself has been understudied <strong>and</strong> misunderstood, but that carries significant l<strong>in</strong>kagesto present-day conditions.Roxane Farmanfarmaian is complet<strong>in</strong>g her PhD at the Centre of International Studiesat the University of Cambridge, where she served as editor of the Cambridge Reviewof International Affairs for three years. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the revolution <strong>in</strong> Iran she foundedThe Iranian, an <strong>in</strong>dependent weekly newsmag<strong>az</strong><strong>in</strong>e. She reported on Iranian affairsfrom Moscow <strong>and</strong> has been a contribut<strong>in</strong>g writer to The New York Times, the ChristianScience Monitor <strong>and</strong> The Times of London. She has guest lectured at the Centre ofMiddle Eastern Studies at UC Berkeley, at Mad<strong>in</strong>gly Hall at Cambridge University<strong>and</strong> has consulted on Iran <strong>and</strong> Iraq for the British Military.Contributors: Peter W. Avery; Stephanie Cron<strong>in</strong>; Manoutchehr M. Esk<strong>and</strong>ari-<strong>Qajar</strong>;Mansoureh Ettehadieh; Roxane Farmanfarmaian; Ali Gheissari; Vanessa Mart<strong>in</strong>;Lawrence G. Potter; Richard Schofield <strong>and</strong> Graham Williamson.

History <strong>and</strong> Society <strong>in</strong> the Islamic WorldSeries editors: Anoushiravan Ehteshami, University ofDurham <strong>and</strong> George Joffé, Centre for International Studies,Cambridge UniversityContemporary events <strong>in</strong> the Islamic world dom<strong>in</strong>ate the headl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong>emphasize the crises of the Middle East <strong>and</strong> North Africa, yet the Islamicworld is far larger <strong>and</strong> more varied than we realize. Current affairs there,too, mask the underly<strong>in</strong>g trends <strong>and</strong> values that have, over time, created afasc<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> complex world. This new series is <strong>in</strong>tended to reveal that otherIslamic reality by look<strong>in</strong>g at its history <strong>and</strong> society over the ages, as well asat the contemporary scene. It will also reach far further afield, br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> Central Asia <strong>and</strong> the Far East as part of a cultural space shar<strong>in</strong>g commonvalues <strong>and</strong> beliefs but manifest<strong>in</strong>g a vast diversity of experience <strong>and</strong>social order.French Military Rule <strong>in</strong> MoroccoColonialism <strong>and</strong> its consequencesMoshe GershovichTribe <strong>and</strong> Society <strong>in</strong>Rural MoroccoDavid M. HartNorth Africa, Islam <strong>and</strong> theMediterranean WorldFrom the Almoravids tothe Algerian <strong>War</strong>Edited by Julia Clancy-SmithThe Walled Arab City <strong>in</strong> Literature,Architecture <strong>and</strong> HistoryThe liv<strong>in</strong>g Med<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> the MaghribEdited by Susan SlyomovicsTribalism <strong>and</strong> Rural Society <strong>in</strong> theIslamic WorldDavid M. HartTechnology, Tradition <strong>and</strong> SurvivalAspects of material culture <strong>in</strong> theMiddle East <strong>and</strong> Central AsiaRichard Tapper <strong>and</strong> KeithMcLachlanLebanonThe politics of frustration – thefailed coup of 1961Adel BesharaBrita<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Morocco Dur<strong>in</strong>g theEmbassy of John Drummond Hay,1845–1886Khalid Ben SrhirThe Assass<strong>in</strong>ation of JacquesLemaigre DubreuilA Frenchman between France<strong>and</strong> North AfricaWilliam A. Hois<strong>in</strong>gton JrPolitical Change <strong>in</strong> AlgeriaElites <strong>and</strong> the balanc<strong>in</strong>g of<strong>in</strong>stabilityIsabelle WerenfelsThe Trans-Saharan Slave TradeJohn WrightCivil Society <strong>and</strong> Political Change<strong>in</strong> MoroccoJames N. Sater<strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Peace</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Persia</strong><strong>Implications</strong> past <strong>and</strong> presentEdited by Roxane Farmanfarmaian

<strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Peace</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Persia</strong><strong>Implications</strong> past <strong>and</strong> presentEdited by Roxane Farmanfarmaian

First published 2008 by Routledge2 Park Square, Milton Park, Ab<strong>in</strong>gdon, Oxon Ox14 4RNSimultaneously published <strong>in</strong> the USA <strong>and</strong> Canadaby Routledge270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016This edition published <strong>in</strong> the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008.“To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’scollection of thous<strong>and</strong>s of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.t<strong>and</strong>f.co.uk.”Routledge is an impr<strong>in</strong>t of the Taylor & Francis Group,an <strong>in</strong>forma bus<strong>in</strong>ess© 2008 Editorial selection <strong>and</strong> matter; Roxane Farmanfarmaian;<strong>in</strong>dividual chapters the contributorsAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be repr<strong>in</strong>ted orreproduced or utilized <strong>in</strong> any form or by any electronic, mechanical,or other means, now known or hereafter <strong>in</strong>vented, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gphotocopy<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> record<strong>in</strong>g, or <strong>in</strong> any <strong>in</strong>formation storage orretrieval system, without permission <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g from the publishers.British Library Catalogu<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryLibrary of Congress Catalog<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Publication Data<strong>War</strong> <strong>and</strong> peace <strong>in</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Persia</strong>: implications past <strong>and</strong> present / editedby Roxane Farmanfarmaian.p. cm.Includes bibliographical references <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dex.1. Iran–History–<strong>Qajar</strong> dynasty, 1794–1925.2. Iran–History, Military. I. Farmanfarmaian, Roxane, 1955–DS299.W37 2008955′.04–dc222007025350ISBN 0-203-93830-5 Master e-book ISBNISBN 10: 0-415-42119-5 (hbk)ISBN 10: 0-203-93830-5 (ebk)ISBN 13: 978-0-415-42119-5 (hbk)ISBN 13: 978-0-203-93830-0 (ebk)

ContentsList of figuresContributorsAcknowledgementsviiviiixiIntroduction 1ROXANE FARMANFARMAIANPrologue: the dream of empire 13PETER W. AVERYPART I<strong>War</strong> 191 Between Scylla <strong>and</strong> Charybdis: policy-mak<strong>in</strong>g under conditionsof constra<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> early <strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Persia</strong> 21MANOUTCHEHR M. ESKANDARI-QAJAR2 Build<strong>in</strong>g a new army: military reform <strong>in</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> Iran 47STEPHANIE CRONIN3 The Turko-<strong>Persia</strong>n <strong>War</strong> of 1821–1823: w<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g the war butlos<strong>in</strong>g the peace 88GRAHAM WILLIAMSON4 Social networks <strong>and</strong> border conflicts: the First Herat <strong>War</strong>1838–1841 110VANESSA MARTIN

viContentsPART II<strong>Peace</strong> 1235 The consolidation of Iran’s frontier on the <strong>Persia</strong>n Gulf<strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century 125LAWRENCE G. POTTER6 Narrow<strong>in</strong>g the frontier: mid-n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century efforts todelimit <strong>and</strong> map the Perso-Ottoman border 149RICHARD SCHOFIELD7 Crime, security, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>security: socio-political conditionsof Iran, 1875–1924 174MANSOUREH ETTEHADIEH (NEZAM-MAFIE)8 Merchants without borders: trade, travel <strong>and</strong> a revolution<strong>in</strong> late <strong>Qajar</strong> Iran (the memoirs of Hajj Mohammad-TaqiJourabchi, 1907–1911) 183ALI GHEISSARI9 The politics of concession: reassess<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>terl<strong>in</strong>kageof <strong>Persia</strong>’s f<strong>in</strong>ances, British <strong>in</strong>trigue <strong>and</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> negotiation 213ROXANE FARMANFARMAIANIndex 229

Figures5.1 Omani enclaves 1305.2 Arab pr<strong>in</strong>cipalities 1376.1 The 1843 borderl<strong>and</strong>s status quo 1536.2 The 1850 Williams l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> rival <strong>Persia</strong>n <strong>and</strong> Ottoman<strong>in</strong>terpretations (to its west <strong>and</strong> east) of the 1847 Shattal-Arab boundary delimitation 1576.3 A reduced section of the 1869 Anglo-RussianCarte Identique 1648.1 1958.2 1968.3 1978.4 1988.5 Taken <strong>in</strong> Hajj Hasan Jourabchi’s house <strong>in</strong> Tabriz 1998.6 2008.7 201

Contributor listPeter Avery’s <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> <strong>Persia</strong>n began <strong>in</strong> India dur<strong>in</strong>g World <strong>War</strong> II <strong>and</strong>was focused ma<strong>in</strong>ly on the desire to read Hafiz <strong>in</strong> the orig<strong>in</strong>al. He spentseveral years <strong>in</strong> Iran after the Second World <strong>War</strong>, hav<strong>in</strong>g taken a degree <strong>in</strong><strong>Persia</strong>n <strong>and</strong> Arabic from the School of Oriental <strong>and</strong> African Studies (SOAS)<strong>in</strong> 1949. From 1949–1951 he was education liaison officer <strong>in</strong> the oil fields,<strong>and</strong> from 1955–1958 he was Personal Assistant to the Senior Manager ofJohn Mowlem, a road build<strong>in</strong>g contractor <strong>in</strong> Southern Iran.In 1958 he was appo<strong>in</strong>ted Lecturer <strong>in</strong> <strong>Persia</strong>n at Cambridge University<strong>and</strong> became a Fellow of K<strong>in</strong>g’s College. He translated <strong>and</strong> published30 poems by Hafiz <strong>in</strong> 1952 (reissued <strong>in</strong> 2003), Modern Iran <strong>in</strong> 1963, <strong>and</strong>a translation of The Mantiqu’t-Tair (The Speech of the Birds) by ‘Altar<strong>in</strong> 1992. S<strong>in</strong>ce his retirement from his lectureship <strong>in</strong> 1990, he has publishedThe Collected Lyrics of Hafiz of Shir<strong>az</strong> (2007) <strong>and</strong> The Spirit of Iran (2007),has written numerous articles <strong>and</strong> has contributed to the EncyclopediaIranica.Stephanie Cron<strong>in</strong> is Iran Heritage Foundation Fellow at the University ofNorthampton. She is the author of The Army <strong>and</strong> the Creation of the PahlaviState <strong>in</strong> Iran, 1910–1926, (I. B. Tauris, 1997) <strong>and</strong> Tribal Politics <strong>in</strong> Iran: RuralConflict <strong>and</strong> the New State, 1921–1941 <strong>and</strong> the editor of The Mak<strong>in</strong>g of ModernIran; State <strong>and</strong> Society under Riza Shah, 1921–1941 (Routledge Curzon, 2003)<strong>and</strong> Reformers <strong>and</strong> Revolutionaries <strong>in</strong> Modern Iran: New Perspectives on theIranian Left (RoutledgeCurzon, 2004).Manoutchehr M. Esk<strong>and</strong>ari-<strong>Qajar</strong> is Founder <strong>and</strong> Director of the Middle EastStudies Program at Santa Barbara City College. He is also Founder <strong>and</strong>President of the International <strong>Qajar</strong> Studies Association (IQSA) <strong>and</strong> aregular contributor to its journal, <strong>Qajar</strong> Studies, now <strong>in</strong> its seventh year. Hisresearch <strong>in</strong>terests are focused on the <strong>Qajar</strong> period. He is co-editor, withFerydoun Barjesteh <strong>and</strong> Sahar Khosrovani, of <strong>Qajar</strong> Era Health, Hygiene<strong>and</strong> Beauty, Rotterdam, Holl<strong>and</strong> 2003 (ISBN: 90-5613-071-4), <strong>and</strong> Guest Editorof <strong>and</strong> contributor to the September 2007 issue of Iranian Studies dedicatedto the proceed<strong>in</strong>gs of the sixth annual IQSA conference of June 2006 on thetheme of “Enterta<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Qajar</strong> Era.”

Contributor listMansoureh Ettehadieh graduated from Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh University with an MA<strong>in</strong> history <strong>in</strong> 1956 <strong>and</strong> obta<strong>in</strong>ed her PhD <strong>in</strong> 1979 from the same University.She taught history <strong>in</strong> the department of history <strong>in</strong> Tehran University from1963 to 2000. She founded the publish<strong>in</strong>g firm Nashr-e Tarikh-e Iran <strong>in</strong> 1983,which specializes <strong>in</strong> the history of the <strong>Qajar</strong> period. She is currently engaged<strong>in</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g on public op<strong>in</strong>ion from 1870 to 1920. She has written <strong>and</strong> coediteda number of works on this period, some of which are: Khaterat vaAsnad Hose<strong>in</strong> Qoli Khan Nezam al-Saltaneh (Three volumes of the Correspondence<strong>and</strong> diaries of Hosse<strong>in</strong> Qoli Khan Nezam al-Saltaneh), 3 volumes,1984, co-edited with S. Sadv<strong>and</strong>ian; Majles va Entekahbat <strong>az</strong> Mashruteh taPayan-e <strong>Qajar</strong>iyeh (Parliament <strong>and</strong> Elections from the Constitutional Revolutionto the end of the <strong>Qajar</strong> Period), 1996; Majmueh Asnad va MokatebateNosrat al-Dowleh Firuz (The Correspondence <strong>and</strong> documents of Nosratal-Dowleh Firuz), 1999, co-edited with S. Pira; Inja Tehran Ast, MajmuehyeMaqalati dar bareh-ye Tehran, 1269HQ/1344 (A Collections of Essays onthe Social <strong>and</strong> Economic Conditions of Tehran, 1850–1925 Reza Qoli KhanNezam al-Saltaneh), 1998; Zendegani Siyasi va Asnad-e Mohajerat (The life<strong>and</strong> the correspondence of Reza Qoli Khan Nezam al-Saltaneh), 3 volumes,2000; <strong>and</strong> Peydayesh va Tahavol-e Ahzab-e Siyasi Mashrutiyat (The Orig<strong>in</strong><strong>and</strong> Development of Political Parties dur<strong>in</strong>g the Constitutional Revolution),repr<strong>in</strong>ted 2002. Ettehadieh has also written two novels: Zendegi BayadKard, Zendegi Khali Nist.Roxane Farmanfarmaian is complet<strong>in</strong>g her PhD at the Centre of InternationalStudies at the University of Cambridge, where she served as editorof the Cambridge Review of International Affairs for three years. Dur<strong>in</strong>g therevolution <strong>in</strong> Iran she founded The Iranian, an <strong>in</strong>dependent weekly newsmag<strong>az</strong><strong>in</strong>e.She reported on Iranian affairs from Moscow <strong>and</strong> has been acontribut<strong>in</strong>g writer to the New York Times, the Christian Science Monitor<strong>and</strong> The Times of London. She has guest lectured at the Centre of MiddleEastern Studies at UC Berkeley, at Mad<strong>in</strong>gley Hall at Cambridge University<strong>and</strong> has consulted on Iran <strong>and</strong> Iraq for the British Military.Ali Gheissari is Professor of History at the University of San Diego withresearch <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tellectual <strong>and</strong> political history of modern Iran.He studied at the Faculty of Law <strong>and</strong> Political Science, Tehran University,<strong>and</strong> at St Antony’s College, Oxford, <strong>and</strong> has held visit<strong>in</strong>g appo<strong>in</strong>tmentsat Tehran University, Oxford University, UCLA, <strong>and</strong> Brown University. Hiswork <strong>in</strong>clude Merchants <strong>in</strong> Tabriz <strong>and</strong> Rasht dur<strong>in</strong>g the Iranian ConstitutionalRevolution, 1906–1911 (edited volume, Tehran: Nashr-e Tarikh-e Iran, 2007);Democracy <strong>in</strong> Iran: History <strong>and</strong> the Quest for Liberty (coauthor, OxfordUniversity Press, 2006); “Despots of the World Unite! Satire <strong>in</strong> the IranianConstitutional Press: Introduc<strong>in</strong>g Majalleh-ye Estebdad, 1907–1908” (<strong>in</strong>Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa <strong>and</strong> the Middle East, 25:2, 2005);<strong>and</strong> Iranian Intellectuals <strong>in</strong> the Twentieth Century (University of TexasPress, 1998 <strong>and</strong> 2007).ix

xContributor listVanessa Mart<strong>in</strong> is Professor of Middle Eastern History at Royal Holloway,University of London. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests cover n<strong>in</strong>eteenth- <strong>and</strong> twentiethcenturyIran. She is the author of The <strong>Qajar</strong> Pact. Protest, Society <strong>and</strong> theState <strong>in</strong> N<strong>in</strong>eteenth Century Iran (I.B. Tauris 2005); Islam <strong>and</strong> Modernism:the Iranian Revolution of 1906 (I B Tauris, 1989).Lawrence G. Potter teaches at Columbia University <strong>and</strong> is Deputy Directorof Gulf/2000, a major research <strong>and</strong> documentation project on the <strong>Persia</strong>nGulf states. He received an M.A. from S.O.A.S. <strong>and</strong> a Ph.D. <strong>in</strong> History fromColumbia. He co-edited three books on the <strong>Persia</strong>n Gulf, the latest be<strong>in</strong>gIran, Iraq <strong>and</strong> the Legacies of <strong>War</strong> (2004), <strong>and</strong> is currently edit<strong>in</strong>g a bookon the history of the <strong>Persia</strong>n Gulf.Richard Schofield is Lecturer <strong>in</strong> Boundary Studies <strong>and</strong> Convenor of theMaster’s programme <strong>in</strong> Geopolitics, Territory <strong>and</strong> Security (formerly InternationalBoundary Studies) at K<strong>in</strong>g’s College, London. He has writtenextensively on territorial aspects of Iran, Arabia <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Persia</strong>n Gulf region<strong>and</strong> is currently writ<strong>in</strong>g a book (with James Denselow), New Iraq, OldNeighbours: Borders, Territoriality <strong>and</strong> Region Hurst & Co./ColumbiaUniversity Press 2007.Graham Williamson lives <strong>in</strong> Hornchurch, Essex, Engl<strong>and</strong>. He has been<strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> military history for many years <strong>and</strong> became fasc<strong>in</strong>ated withthe history of the early <strong>Qajar</strong> rulers. He has had articles published <strong>in</strong> theJournals of the International <strong>Qajar</strong> Studies Association, Cont<strong>in</strong>ental <strong>War</strong>Society <strong>and</strong> the Iran Society.

AcknowledgementsThis volume grew out of a Conference of the same name held at Corpus ChristiCollege, Cambridge <strong>in</strong> July 2005. The Conference was co-hosted by theInternational <strong>Qajar</strong> Studies Association, the Centre of International Studiesat Cambridge University <strong>and</strong> the Cambridge Security Programme. The publicationof this collection was made possible by the International <strong>Qajar</strong> StudiesAssociation <strong>and</strong> by the Cambridge Security Programme.Special thanks go to Professor George Joffé, co-editor of the “History <strong>and</strong>Society <strong>in</strong> the Islamic World” series, whose advice throughout the processof edit<strong>in</strong>g this volume has been critical. Additionally the editor wishes to thankthe publisher, Routledge, <strong>and</strong> the anonymous readers it provided, for their<strong>in</strong>sights, which have contributed materially to the quality of this volume.

IntroductionRoxane Farmanfarmaian*Historical revisionism can be both dangerous <strong>and</strong> liberat<strong>in</strong>g. To reth<strong>in</strong>k <strong>and</strong>recalibrate the mean<strong>in</strong>gs of the past, imputed by chroniclers of currentevents, is to deny the viewpo<strong>in</strong>t of the witness. This is not a process to betaken lightly. And yet, without the benefit of temporal distance, cross-culturalcomparison <strong>and</strong> political, social <strong>and</strong> economic context to better underst<strong>and</strong>the motives <strong>and</strong> tactics of men <strong>and</strong> empires, history rema<strong>in</strong>s impoverished<strong>and</strong> the lessons to be drawn today rema<strong>in</strong> oblique, if not pla<strong>in</strong> wrong. It isonly <strong>in</strong> the recognition <strong>and</strong> analysis of ongo<strong>in</strong>g trends <strong>and</strong> human responsesover time, what Braudel called “la longue durée”, that history comes <strong>in</strong>to focus,<strong>and</strong> can provide <strong>in</strong>sight for both policymakers <strong>and</strong> academics. Thus, historyis constantly <strong>in</strong> the mak<strong>in</strong>g, an ongo<strong>in</strong>g process of <strong>in</strong>terpretation that beg<strong>in</strong>sas events unfold but then cont<strong>in</strong>ues from then on.It is not uncommon, of course, for the spyglass of historical <strong>in</strong>terest to befickle, <strong>and</strong> ignore certa<strong>in</strong> events <strong>and</strong> eras while favour<strong>in</strong>g others – that is, to bedrawn to popular periods <strong>and</strong> places, <strong>and</strong> only by chance or through eccentricfocus, to discover other, more obscure subjects upon which to turn its enquir<strong>in</strong>gg<strong>az</strong>e. However, wars <strong>and</strong> dynasties – the death, dom<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>and</strong> governanceof men, particularly <strong>in</strong> regions of strife <strong>and</strong> crisis – rema<strong>in</strong> history’sfocus, especially the more recent they are, for history thrives on documents,<strong>and</strong> documents are the fodder of the modern world.It may be deemed surpris<strong>in</strong>g then, that a state at the heart of a still moderatelyrecent, <strong>in</strong>tensely critical area of <strong>in</strong>ternational relations, sufficientlyfraught with the implications of territory <strong>and</strong> empire that it became knownas the Great Game, should itself have rema<strong>in</strong>ed largely ignored by the criticaleye of historical enquiry. With<strong>in</strong> the rich analyses by the Ottomans, theRussians, the British <strong>and</strong> the French dur<strong>in</strong>g the period stretch<strong>in</strong>g generouslyacross the century marks at both ends of the 1800s, evaluation of <strong>Persia</strong> underthe <strong>Qajar</strong>s rema<strong>in</strong>s strangely wooden. Descriptions of the <strong>Qajar</strong>s as condemn<strong>in</strong>gtheir country to decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> foreign dependence because of the Shahs’ <strong>in</strong>competence,avarice <strong>and</strong> corruption rema<strong>in</strong> as unvary<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> unchallenged asthe assumptions of their military failures <strong>and</strong> their <strong>in</strong>ability to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>Persia</strong>’sterritorial <strong>in</strong>tegrity.These views echo those of many, though not all, of the witnesses of eventsat the time, diplomats, travellers, military personnel <strong>and</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>essmen who

2 Roxane Farmanfarmaianrepresented or were citizens of the Great Powers, <strong>and</strong> who understoodthe turmoil of politics, war <strong>and</strong> social upheaval from the perspective of theforeigner, <strong>and</strong> usually, the European. To many of these chroniclers, eventhose with s<strong>in</strong>cere generosity of heart, the <strong>Persia</strong>ns were enigmatic <strong>and</strong> often<strong>in</strong>comprehensible, particularly <strong>in</strong> their often oblique <strong>in</strong>terpretation of theEuropean habits <strong>and</strong> practices be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong>to <strong>Persia</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g this earlymodern period. What is more, their own vest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Persia</strong> was often veryhigh, whether territorially (particularly the Russians to the north <strong>and</strong>, eventually,the British to the east), or f<strong>in</strong>ancially (especially <strong>in</strong> the later years forthe British, once the concessions began, most importantly that of oil). Althoughoften accused of be<strong>in</strong>g dangerous because it was weak, <strong>Persia</strong> representedpower to those who were strong. The efforts of her leaders to exercise theirown control over the divisions of power were, not surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, viewed witha jaundiced eye by those who wished them either more pliant or more decisive,less Oriental <strong>and</strong> more European, more controllable <strong>in</strong> a word, becauseof <strong>Persia</strong>’s matchless geopolitical position – a situation that is strongly echoedtoday. Be<strong>in</strong>g uncompliant to the end would earn the <strong>Qajar</strong>s a reputation thathas dogged them for three-quarters of a century, <strong>and</strong> by the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g ofthe twentieth century, reduced the country to the status of rogue, ripe forregime change, with no supporters to <strong>in</strong>clude it <strong>in</strong> the community of nationsthat met at the Paris <strong>Peace</strong> Conference to reth<strong>in</strong>k the Middle East.With the departure of the <strong>Qajar</strong>s, the era was purposely ignored by thePahlavis, who, like many successor dynasties <strong>in</strong> history, kept the records ofthe past <strong>in</strong> shadow not only for the sake of their own reputation, but todist<strong>in</strong>guish their actions from those of their predecessors, <strong>and</strong> to controlthe idea that what they brought was both new <strong>and</strong> better. It is axiomaticthat history is written by the victors, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> this case, the victors at homerobed the era <strong>in</strong> enforced silence, <strong>and</strong> the victors abroad relied on establishedimageries of the past. The <strong>Qajar</strong> era rema<strong>in</strong>ed, <strong>and</strong> to a great extent,still rema<strong>in</strong>s, on the one h<strong>and</strong> caught <strong>in</strong> the codification of its orig<strong>in</strong>al presentation,<strong>and</strong> on the other h<strong>and</strong>, prist<strong>in</strong>e.Much of what has been written <strong>and</strong> widely dissem<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong>side <strong>and</strong>outside Iran, <strong>and</strong> which constituted the received wisdom concern<strong>in</strong>g the<strong>Qajar</strong>s, was penned close to the period, when Western norms concern<strong>in</strong>g thecentralization of the state, the value of big bus<strong>in</strong>ess, the social benefits ofurbanization <strong>and</strong> the culture of progress were still concepts that were largelyunassailed, primarily as no alternative had yet been suggested by practicalexperience. The exception was the Bolshevik revolution <strong>in</strong> Russia, thougheven this, despite be<strong>in</strong>g ideologically a challenge to Western foundations ofeconomic or social structur<strong>in</strong>g, did not fundamentally question the centralizationof the state, the technological bases of progress, or, <strong>and</strong> most particularly,secularization as a build<strong>in</strong>g block of modernity.For current scholars, this period offers a rich <strong>and</strong> still largely untrammelledfield for <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation; it also offers the opportunity todiscover patterns <strong>in</strong> the past that may have relevance to current events. The

Introduction 3level of scholarly engagement <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Qajar</strong> era has risen exponentially overthe past two decades s<strong>in</strong>ce the fall of the Pahlavi dynasty, effected both bya re<strong>in</strong>terpretation of exist<strong>in</strong>g material <strong>and</strong> access to the vast troves of newlyavailable documents, artefacts <strong>and</strong> images from the Court archives <strong>and</strong> fromthe various libraries not only <strong>in</strong> Iran, but <strong>in</strong> such places as Georgia <strong>and</strong> Russia.What is more, there is now a level of debate about a range of issues of importancedur<strong>in</strong>g that period, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g questions of law <strong>and</strong> constitutionalism,f<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>and</strong> development, military capability <strong>and</strong> social organization, thatdid not exist before <strong>and</strong> which is help<strong>in</strong>g to reduce the previous politicizationof <strong>Qajar</strong> studies <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>in</strong>spire a legitimate body of scholarly literature.The freighted subject of territorial <strong>in</strong>tegrity, for example, <strong>and</strong> how itrelated to historical conceptions of <strong>Persia</strong> proper, the expansion of empire <strong>and</strong>the def<strong>in</strong>ition of boundaries has become a hotly contested area of scholarly<strong>in</strong>terest as new material <strong>and</strong> analysis has opened up debate on the constra<strong>in</strong>tsfaced by the <strong>Qajar</strong> rulers at the time, <strong>and</strong> what they meant to the prosecutionof war <strong>and</strong> diplomacy, as well as to the balance between domestic <strong>and</strong>foreign dem<strong>and</strong>s. The different views of how the <strong>Qajar</strong>s addressed <strong>and</strong> managedthe territory of <strong>Persia</strong> <strong>and</strong> the treaties that attempted to lock the borders<strong>in</strong>to their current position, colour as well as <strong>in</strong>form how related issues areunderstood, <strong>and</strong>, as can be seen throughout this volume, many unresolvedquestions rema<strong>in</strong>. What is clear is that a significant domestic dimension,hitherto discounted or misconstrued, exercised an important role <strong>in</strong> theoutcomes of the Great Game. The debate reveals that our underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g ofthe complexities of the Great Game (<strong>and</strong> what it may illum<strong>in</strong>ate concern<strong>in</strong>gcurrent geopolitical <strong>in</strong>teractions between the West <strong>and</strong> the Gulf ) hasmuch to ga<strong>in</strong> from a more thorough <strong>in</strong>vestigation of the <strong>Persia</strong>n historicalperspective.The establishment of the International <strong>Qajar</strong> Studies Association (IQSA)<strong>in</strong> 2000, as well as the sett<strong>in</strong>g aside of funds from many sources for the studyof various aspects of the <strong>Qajar</strong> era, has resulted <strong>in</strong> a plethora of new publications,conferences <strong>and</strong> analyses of a complex state with one side of its faceturned to the traditional Orient <strong>and</strong> one to the moderniz<strong>in</strong>g world, while be<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> the crosshairs of a territorial struggle of momentous dimension betweenthe world’s greatest powers. In fact, although other aspects of <strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Persia</strong>,such as the role of the clergy, have been the subject of <strong>in</strong>itial scholarly treatmentprior to this time, the issue of war <strong>and</strong> the adm<strong>in</strong>istration of the periodsof peace that ensued has been s<strong>in</strong>gularly lack<strong>in</strong>g. Previously understood<strong>and</strong> judged largely from the outside, both culturally <strong>and</strong> strategically, <strong>Qajar</strong><strong>Persia</strong>, the pivot around which the Great Game turned, <strong>and</strong> which nonethelessdefied colonial or other foreign takeover, is now be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>vestigated onher own terms, or <strong>in</strong> relation to her near abroad, vantage po<strong>in</strong>ts that offera completely different read<strong>in</strong>g of history.What is more, political, economic <strong>and</strong> social theories are be<strong>in</strong>g utilizedfor the sake of locat<strong>in</strong>g aspects of <strong>Qajar</strong> history with<strong>in</strong> a rigorous scholarlyframework. It is with<strong>in</strong> such a framework that Manoutchehr Esk<strong>and</strong>ari-<strong>Qajar</strong>’s

4 Roxane Farmanfarmaianchapter <strong>in</strong> this volume, “Between Scylla <strong>and</strong> Charybdis: policy-mak<strong>in</strong>g underconstra<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> early <strong>Qajar</strong> <strong>Persia</strong>”, for example, grapples with that greatestscourge of the <strong>Qajar</strong>’s reputation referred to above, its apparent <strong>in</strong>ability toma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>Persia</strong>’s territorial <strong>in</strong>tegrity, <strong>and</strong> hence, its “loss” to Russia <strong>and</strong> theOttomans (<strong>and</strong> to the British, via Afghanistan) of vast tracks of <strong>Persia</strong>n l<strong>and</strong>.In analyz<strong>in</strong>g this question dur<strong>in</strong>g the critical period <strong>in</strong> which the Treaty ofTurkomanchay was drawn up – a Treaty generally deemed <strong>in</strong> the literatureto reveal serious <strong>in</strong>eptitude at the court of Fath-Ali Shah – Esk<strong>and</strong>ari-<strong>Qajar</strong>unpicks the decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g that took place <strong>in</strong> terms of trade-offs betweenga<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> losses, locat<strong>in</strong>g his analysis with<strong>in</strong> the theoretical constructs ofprospect <strong>and</strong> rational decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g theory. By shift<strong>in</strong>g the viewpo<strong>in</strong>t so thatthe options be<strong>in</strong>g faced by Tehran are the focus of <strong>in</strong>vestigation, Esk<strong>and</strong>ari-<strong>Qajar</strong> draws several surpris<strong>in</strong>g conclusions that suggest an alternative paradigmby which to underst<strong>and</strong> the progression of events <strong>and</strong> their outcomes. Theprocess he outl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong>troduces a set of imperatives whose role has previouslybeen ill understood, both <strong>in</strong> terms of historical conceptions of <strong>Persia</strong>’s territorypropre <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> terms of Fath-Ali Shah’s need to respond to developmentson his borders that <strong>in</strong> fact reflected shifts <strong>in</strong> power relations tak<strong>in</strong>g place <strong>in</strong>Europe between Russia, Brita<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> France, <strong>and</strong> thus well beyond his scopeof control.The result of these revisionist <strong>in</strong>vestigations based on exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> newmaterial are narratives that are not only more rounded, but also suggestsignificantly different motivations than previously considered (<strong>and</strong> assumed)<strong>in</strong> regards to decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g, resource-management, border adm<strong>in</strong>istration,local (social) <strong>in</strong>fluences or geopolitical identity. The <strong>Persia</strong> that emerges isone of relative political stability, notwithst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g the turmoil on all sidesof her borders; one of <strong>in</strong>dependence from the colonial practices that characterizedthe <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>in</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>s of her neighbours; <strong>and</strong> one that, despitesignificant pressures from the outside on her trade, currency <strong>and</strong> otherresources, enjoyed a regime cont<strong>in</strong>uity that was unique <strong>in</strong> the geopoliticalregion she occupied. On the one h<strong>and</strong>, as Mansoureh Ettehadieh describes<strong>in</strong> her chapter, draw<strong>in</strong>g on new empirical <strong>in</strong>formation on brig<strong>and</strong>ry, security<strong>and</strong> crime, <strong>and</strong> as Gheissari po<strong>in</strong>ts out <strong>in</strong> his study on merchant life <strong>in</strong> Tabrizdur<strong>in</strong>g the revolutionary period, foreign occupation, <strong>in</strong>ternal constitutionalupheavals <strong>and</strong> economic pressures significantly <strong>in</strong>terrupted trade <strong>and</strong> reducedthe level of social safety, particularly towards the end of the <strong>Qajar</strong> era. Onthe other h<strong>and</strong>, there was a consistent, if often thwarted, commitment to gradualreform economically, politically <strong>and</strong> militarily, which cont<strong>in</strong>ued despitehuge setbacks, <strong>and</strong> can be seen to have been a hallmark of this early modernperiod of <strong>Persia</strong>n history. Although this is not to say that corruption,mismanagement of the state <strong>and</strong> hardship did not accompany the enormouschanges be<strong>in</strong>g experienced <strong>in</strong> the course of the wars <strong>and</strong> periods of uneasypeace that followed so close upon one another as the century progressed,they can no longer be considered, as the chapters <strong>in</strong> this volume clearly <strong>in</strong>dicate,the only elements that def<strong>in</strong>e the <strong>Qajar</strong> reign.

WAR AND PEACEIntroduction 5In address<strong>in</strong>g the matrix of war <strong>and</strong> peace, the contributions <strong>in</strong> this collection,though not able to cover the entire gamut of possible academic enquiry,nonetheless take up questions that are fundamental to underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g the GreatGame <strong>and</strong> the relationship not just of the government, but of the <strong>Persia</strong>npeople, to the economic, political <strong>and</strong> regional pressures which the countryencountered at that critical time. What emerges is a picture of a state whichoffers perhaps unexpectedly useful comparison with the contemporaryworld <strong>in</strong> at least two significant ways: <strong>in</strong> terms of its geopolitical position<strong>and</strong> its resource management.Dur<strong>in</strong>g the reign of the <strong>Qajar</strong>s, pressures were be<strong>in</strong>g exerted upon the countryfrom three directions: the north from Russia; the east from British India<strong>and</strong> the new buffer state of Afghanistan; <strong>and</strong> the west from the Ottomans<strong>and</strong> the British <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Persia</strong>n Gulf. For the <strong>Qajar</strong>s, the focus of both their<strong>in</strong>ternal <strong>and</strong> foreign relations, therefore, was on resistance to external penetration.This had structural as well as ideological implications. First, it requireda new approach to the organization of the state – that is, toward a centralizationof control, not only over the management of governance, but significantly,over military capability, a move that gradually <strong>in</strong>volved replac<strong>in</strong>gthe networked structure of tribal <strong>and</strong> feudal loyalties which had until thendef<strong>in</strong>ed a distributed military system of power, to one formally led <strong>and</strong> paidfor from the centre. This reconfiguration, with its reverberations through boththe social <strong>and</strong> political spheres, was begun by the <strong>Qajar</strong>s as a response to <strong>Persia</strong>’sgeopolitical vulnerability to the <strong>in</strong>terventions of the Great Game, <strong>and</strong> theneed for managed military campaigns to fend off when necessary – <strong>and</strong> often,simultaneously – the modern, technological advances of the Great Powers.Perhaps the best examples are the two Herat <strong>War</strong>s, <strong>in</strong> which Brita<strong>in</strong> attackedKharg Isl<strong>and</strong> (<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Second Herat <strong>War</strong>, Bushehr <strong>and</strong> Mohammerah)from the west, <strong>in</strong> order to settle the ongo<strong>in</strong>g conflict over Herat <strong>in</strong> the east. AsVanessa Mart<strong>in</strong> illustrates, however, <strong>in</strong> her study of the effect of social networkson foreign policy dur<strong>in</strong>g the First Herat <strong>War</strong>, the process of centralizationwas not an easy – or from the po<strong>in</strong>t of view of the local populations,an immediately obvious – one, <strong>and</strong> cooperation between the Shah <strong>and</strong> the tribesor cities, <strong>in</strong> their mutual need to protect <strong>Persia</strong>’s borders, often broke down.Second, the need to protect aga<strong>in</strong>st external penetration, <strong>and</strong> hence, to assurethe cont<strong>in</strong>uance of the “nation” of <strong>Persia</strong>, shifted the emphasis on secur<strong>in</strong>gthe state by means other than the use of direct force, that is, through negotiation,frequently through third parties. With vary<strong>in</strong>g degrees of success, thisdevelopment <strong>in</strong>troduced a new ideological basis upon which loyalty <strong>and</strong> engagementwith the centre would become evident, namely on a popular conceptionof “national identity”. This would eventually f<strong>in</strong>d its expression <strong>in</strong> theConstitutional Revolution, which would take place even as <strong>Persia</strong> was f<strong>in</strong>allyformally divided <strong>in</strong>to spheres of foreign <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>in</strong> the Anglo-RussianAgreement of 1907.

6 Roxane FarmanfarmaianThus, two significant domestic trends began to take place <strong>in</strong>side <strong>Persia</strong> <strong>in</strong>response to the fact that there were contested borders on three sides of <strong>Persia</strong>’sterritory dur<strong>in</strong>g this period. By implication, this historical moment can beunderstood to have constituted a critical era of border def<strong>in</strong>ition, which ledto military (<strong>and</strong> state) modernization <strong>and</strong> the genesis of a modern sense of<strong>Persia</strong>n national identity.THE GEOPOLITICAL FACTORFrom the very early years of the <strong>Qajar</strong> dynasty, the Russo-<strong>Persia</strong>n <strong>War</strong>(1811–1813) began the process of a modern confrontation with Europeanmilitary technology <strong>and</strong> methods that <strong>in</strong>spired Fath-Ali Shah <strong>and</strong> his successorsto follow <strong>in</strong> the footsteps of the Ottomans (<strong>and</strong> Egyptians) <strong>and</strong> attemptmilitary reform for the sake of protect<strong>in</strong>g the territorial boundaries of thestate. Although Stephanie Cron<strong>in</strong> suggests <strong>in</strong> “Build<strong>in</strong>g a new army: militaryreform <strong>in</strong> <strong>Qajar</strong> Iran” that <strong>in</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>al analysis, the guerrilla warfare practisedby the horse-mounted tribes was probably more efficacious aga<strong>in</strong>st theformations of the Russian (<strong>and</strong> later Ottoman <strong>and</strong> British) armies, the courtnonetheless attempted throughout the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century to Europeanize.To this end, it focused on develop<strong>in</strong>g a modern <strong>in</strong>fantry while eclips<strong>in</strong>g itscavalry, which it did by br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>Persia</strong> successive foreign militaryexperts, none of whom fully succeeded <strong>in</strong> strengthen<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Persia</strong>n forcessufficiently to enable real protection of its borders through military exploit.Nonetheless, as Graham Williamson argues <strong>in</strong> his <strong>in</strong>vestigation of the warsprosecuted by Fath-Ali Shah’s two sons, the Crown Pr<strong>in</strong>ce Abbas Mirza <strong>in</strong>the northwest <strong>and</strong> Azerbaijan, <strong>and</strong> Mohammad Ali Mirza <strong>in</strong> the southwest<strong>and</strong> aga<strong>in</strong>st Baghdad, the <strong>Persia</strong>n mastery of new military practices <strong>and</strong>technology was sufficiently successful that both pr<strong>in</strong>ces were able to w<strong>in</strong>decisive battles aga<strong>in</strong>st what were considerably larger <strong>and</strong> better equippedOttoman armies. Williamson starkly illustrates, however, <strong>in</strong> “The Turko-<strong>Persia</strong>n <strong>War</strong> of 1821–1823: w<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g the war but los<strong>in</strong>g the peace” that militaryprowess on the field was <strong>in</strong> itself not sufficient when the state lackedthe centralized mechanisms (f<strong>in</strong>ancial or organizational) to feed <strong>and</strong> quartera st<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g national army, <strong>and</strong> thus hold the territory that had been ga<strong>in</strong>edthrough battlefield success. Despite the military conquests <strong>in</strong> the Turko-<strong>Persia</strong>n<strong>War</strong> that <strong>in</strong> fact accrued to <strong>Persia</strong>, therefore, Williamson contends that thepeace was lost because of the complex play of loyalties, tribal as well as religious,which extended across a broad b<strong>and</strong> of fickle territory that only roughlydel<strong>in</strong>eated Ottoman Azarbaijan <strong>and</strong> Ottoman Iraq from <strong>Persia</strong>. Here,suzera<strong>in</strong>ty could be shifted from one side to the other as easily through f<strong>in</strong>ancial<strong>in</strong>centive, tribal fealty <strong>and</strong> the bl<strong>and</strong>ishments of religious affiliation asthrough military conquest. What Williamson h<strong>in</strong>ts at <strong>in</strong> his analysis of the playalong the Iran–Iraq border between religious extremists (which <strong>in</strong>cluded astrong stra<strong>in</strong> of resurgent Wahhabism), tribal b<strong>and</strong>itry <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent holy

Introduction 7city states, is a situation strik<strong>in</strong>gly rem<strong>in</strong>iscent of the region’s tumult today,a zone of lawlessness <strong>in</strong> which local populations <strong>in</strong> the midst of war havelittle <strong>in</strong>centive to compromize with any of the far-off centres of authority.The concept of a border as a demarcated l<strong>in</strong>e between nations (thus representativeof differently affiliated peoples), <strong>and</strong> which was imposed by externalpowers, is taken up by K<strong>in</strong>g’s College geographer Richard Schofield. In hischapter, “Narrow<strong>in</strong>g the frontier: mid-n<strong>in</strong>eteenth-century efforts to delimit,map <strong>and</strong> demarcate the Perso-Ottoman border”, he describes the tortuousprocess, fraught with <strong>in</strong>trigue, improbity <strong>and</strong> foreign schemes, that was <strong>in</strong>volved<strong>in</strong> draw<strong>in</strong>g the boundary between what are present-day Iran <strong>and</strong> Iraq – anundertak<strong>in</strong>g that was repeated by other border commissions organized byboth the British <strong>and</strong> Russians <strong>in</strong> <strong>Persia</strong>’s southeast as well as northeast. Ineffect, the 1847 Treaty of Erzurum, drawn up between <strong>Persia</strong> <strong>and</strong> Turkey,del<strong>in</strong>eated the Middle East’s first real negotiated border; <strong>in</strong> this, the Ottomans“expressly recognized that the anchorage of Mohammerah <strong>and</strong> the l<strong>and</strong>s eastof the Shatt al-Arab belong<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>Persia</strong>n tribes were <strong>Persia</strong>n territory”. 1Although, like most of the other borders established by negotiation <strong>and</strong> thework of commissions, the process took years, be<strong>in</strong>g subject to dispute <strong>and</strong>renegotiation <strong>in</strong> all cases. However, the process which evolved was to marka significant milestone <strong>in</strong> the establishment of suzera<strong>in</strong>ty over territory <strong>in</strong> theMiddle East, <strong>and</strong> the reversal of the role of war <strong>and</strong> peace <strong>in</strong> establish<strong>in</strong>g it.Strict borders, l<strong>in</strong>es upon a page, as Schofield observes, were a European,not a Middle Eastern, concept. Previously, the boundaries of <strong>Persia</strong>, <strong>in</strong> thesame way as the other states <strong>in</strong> the region, were <strong>in</strong> fact “borderl<strong>and</strong>s”, dozens,if not hundreds, of miles wide, areas of fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g patronage <strong>and</strong> liege thatdid not themselves <strong>in</strong>volve the same suspicion <strong>and</strong> conflict between adjacentpowers that arose once strict l<strong>in</strong>es were drawn <strong>in</strong> the s<strong>and</strong>. The impositionof marked boundaries by Brita<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Russia upon the <strong>Persia</strong>n <strong>and</strong> Ottomanrulers was therefore a European project for European purposes (even thoughthey never succeeded <strong>in</strong> gett<strong>in</strong>g the l<strong>in</strong>es as perfectly settled as they had wished),<strong>and</strong> had the unexpected result of caus<strong>in</strong>g border friction between <strong>Persia</strong> <strong>and</strong>her neighbours where previously there had been none. Because of its criticalgeopolitical position, <strong>Persia</strong> became the first country <strong>in</strong> the Muslim worldwhose borders were so def<strong>in</strong>ed; North Africa would have its borders del<strong>in</strong>eatedonly later <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century; the Gulf states <strong>and</strong> the rest of the MiddleEast would not have their borders ruled until post-World <strong>War</strong> I.Even so, Schofield describes a process that was neither efficient nor def<strong>in</strong>itive.After many years of negotiation, the western border of Iran rema<strong>in</strong>ed fungible<strong>and</strong> open to dispute, a fact that cont<strong>in</strong>ues to bedevil its relations withIraq <strong>in</strong>, for example, the Shatt-al Arab <strong>and</strong> the marsh areas to its north, <strong>and</strong>which renders the mathematical accuracy of today’s Global Position<strong>in</strong>gSystem largely irrelevant.More successful was <strong>Persia</strong>’s own extension of <strong>in</strong>disputable dom<strong>in</strong>ion overthe coastl<strong>in</strong>e of the <strong>Persia</strong>n Gulf, a process which was a direct result of theextension of centralized power outwards from Tehran. With the <strong>in</strong>centive of

8 Roxane Farmanfarmaianga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g greater revenue by tak<strong>in</strong>g over control of the customs receipts of theprosperous port cities, the various Arab tribes that had occupied the easterncoast of the Gulf were gradually eased out, leav<strong>in</strong>g the Omanis <strong>and</strong> British– the two ma<strong>in</strong> naval powers – as the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal entities with which the <strong>Qajar</strong>state had to negotiate. By the end of the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century, all but Bushehr,still a British enclave, <strong>and</strong> Mohammerah, the doma<strong>in</strong> of Sheikh Kh<strong>az</strong>al, cameunder <strong>Qajar</strong> control – <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the rich port of B<strong>and</strong>ar Abbas. Here, asVanessa Mart<strong>in</strong> po<strong>in</strong>ts out, the local populace rema<strong>in</strong>ed an important factor<strong>in</strong> driv<strong>in</strong>g out both the Omani <strong>and</strong> British presence, s<strong>in</strong>ce the pride of localleaders <strong>and</strong> merchants <strong>in</strong> the Shah’s ability to promote <strong>Persia</strong>n national prestige(<strong>and</strong> hence, sense of “nation”) proved as important as any later nuanceof negotiation or force of arms. Though Mart<strong>in</strong> argues that Mohammad Shah’sability to generate funds from the populations located <strong>in</strong> the north for thecampaigns aga<strong>in</strong>st the Russians rema<strong>in</strong>ed severely hampered dur<strong>in</strong>g this period,social groups <strong>in</strong> the south were more able to turn the conflict to their ownf<strong>in</strong>ancial advantage – <strong>and</strong> by association, <strong>Persia</strong>n dom<strong>in</strong>ance along the littoral.The critical change brought about by the extension of <strong>Qajar</strong> control overthe Gulf coast at the expense of the power of both Oman <strong>and</strong> the BritishEmpire came towards the second half of the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century, accord<strong>in</strong>gto Lawrence Potter, when the dynasty at last acquired several ships, form<strong>in</strong>gthe beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>gs of a navy. In “The consolidation of Iran’s frontier on the <strong>Persia</strong>nGulf <strong>in</strong> the n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century”, Potter traces the gradual changeover ofcontrol from the Arab tribes, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the Sultanate of Muscat, which haddom<strong>in</strong>ated the depot towns <strong>and</strong> farmed their customs through lease, to that ofthe <strong>Persia</strong>n state, at first adm<strong>in</strong>istered from Shir<strong>az</strong>, <strong>and</strong> then later controlledby Tehran. Although he argues that the acquisition of ships was itself<strong>in</strong>significant, as they did not constitute a naval force per se, the action representedthe concentration of <strong>Qajar</strong> power over the entire coast, encourag<strong>in</strong>ga conception of the eastern littoral of the Gulf as <strong>Persia</strong>n, even by theBritish, who were among the consolidation’s greatest detractors.RESOURCE SCARCITY AND PROTECTIONA second theme that runs throughout the chapters <strong>in</strong> this collection, <strong>and</strong> istaken up as a ma<strong>in</strong> focus of research <strong>in</strong> Roxane Farmanfarmaian’s chapter,“The politics of concession”, is that of the <strong>Qajar</strong>’s cont<strong>in</strong>uous lack of f<strong>in</strong>ancialresources, <strong>and</strong> the grow<strong>in</strong>g currency difficulties they faced. This was dueto three ma<strong>in</strong> factors. First, the usurious terms imposed on the state follow<strong>in</strong>gthe Treaty of Golestan (<strong>and</strong> later, the Treaty of Turkomanchai) by theRussians, who established a “most favoured nation” system of duties on trade,which was eventually copied by the British. Second, the gradual shift <strong>in</strong> traderoutes away from <strong>Persia</strong> as a product of the Great Game. Third, the silverbasis of the currency, which gradually lost value on the <strong>in</strong>ternational marketas vast quantities of silver were released from the American West, while

Introduction 9at the same time a majority of countries shifted their currency basis fromsilver to gold, leav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Persia</strong>’s currency virtually isolated by the turn of thecentury.Until the discovery of oil <strong>in</strong> 1911, the <strong>Qajar</strong>s had access to three ma<strong>in</strong>resources by which to keep the economy afloat <strong>and</strong> the currency from decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g:trade, <strong>in</strong> which the export of <strong>Persia</strong>n goods, as well as the service oftransit goods, earned valuable lucre, as well as serv<strong>in</strong>g to br<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> gold co<strong>in</strong>agefrom abroad; customs duty farm<strong>in</strong>g at border posts <strong>and</strong> port cities; <strong>and</strong>, beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>gwith the reign of Nasser-ed<strong>in</strong> Shah, the sale of concessions. Spoils ofconquest, which had fuelled previous military campaigns, <strong>and</strong> added to thetreasure trove of gold <strong>and</strong> silver bullion at the royal treasury, were no longera factor once the stability of the <strong>Qajar</strong>s was established, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stead, the outflow(<strong>and</strong> popular hoard<strong>in</strong>g) of gold began to empty the state’s coffers. In today’sparlance, therefore, the <strong>Qajar</strong> economy can be seen to have been largely aservice economy focused on import/export, <strong>and</strong> on facilitat<strong>in</strong>g trade acrossits many borders. The rerout<strong>in</strong>g of trade was the result, not only of politicalconsiderations of the Great Game, but also of technological developments <strong>in</strong>naval <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> transportation. This shifted the trade routes first from aneast–west axis to a north–south axis, <strong>and</strong> then served to dry up trade quitesubstantially as the routes circumvented <strong>Persia</strong> through the Black Sea to thenorth, or from the Gulf through Baghdad along the railroad to Europe <strong>in</strong>the west. As a result, revenues dropped, even as <strong>Persia</strong>’s debts rose. Cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> its tradition of turn<strong>in</strong>g to Western experts for help <strong>in</strong> moderniz<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> organiz<strong>in</strong>g its affairs, <strong>Persia</strong> <strong>in</strong>vited a Belgian official to take overthe management of its customs, <strong>and</strong> he was succeeded by Morgan Shuster<strong>and</strong> J. Millspaugh from the United States to more broadly sort out <strong>Persia</strong>’sf<strong>in</strong>ances.As has amply been recorded, Nasser-ed<strong>in</strong> Shah, when faced with this sorry(<strong>and</strong> seem<strong>in</strong>gly hopeless) state of affairs, travelled to Europe to observe westernmethods of <strong>in</strong>dustrialization <strong>and</strong> economic practice, encounter<strong>in</strong>g concessionhunters along the way to whom he began award<strong>in</strong>g concessions uponhis return to Tehran. Often accused <strong>in</strong> the literature of hav<strong>in</strong>g sold <strong>Persia</strong>’sresources for his own ga<strong>in</strong>, an alternative argument po<strong>in</strong>ts to <strong>Persia</strong>’s direneed to prop up its currency <strong>and</strong> contribute <strong>in</strong> new ways to its economicproductivity, both of which could be achieved <strong>in</strong> jo<strong>in</strong>t ventures with foreignbus<strong>in</strong>esses. The concessionary practice can be seen to have evolved directlyfrom <strong>Persia</strong>’s already established tradition of work<strong>in</strong>g with foreign advisors<strong>and</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess enterprises <strong>in</strong> various other sectors – <strong>and</strong> the structure of theconcessionary agreements, despite be<strong>in</strong>g a new area of contract design, reflectsa degree of economic sophistication with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>Qajar</strong> court which only thedistance of time <strong>and</strong> comparison with other concessions elsewhere, have madeclear. This is not to say that serious errors were not made, as <strong>in</strong> the case ofthe Tobacco Concession, perhaps the most egregious example of the knavery,cut-throat competition <strong>and</strong> multiple payoffs which characterized the concessionbus<strong>in</strong>ess at its worst. However, as Farmanfarmaian argues, the <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly

10 Roxane Farmanfarmaiantough deals, which revealed the <strong>Persia</strong>n government learn<strong>in</strong>g from itsmistakes <strong>and</strong> push<strong>in</strong>g the concessionary each time for higher returns <strong>and</strong> greater<strong>Persia</strong>n control, were hammered out despite collusion between European government<strong>and</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess representatives, a situation that reached its p<strong>in</strong>nacle ofabuse <strong>in</strong> the manipulation of the oil concession <strong>in</strong> the south by the Britishgovernment. Although detailed records of the <strong>Persia</strong>n debates <strong>and</strong> decisionsconcern<strong>in</strong>g the concessions have yet to come to light, a close read<strong>in</strong>g of BritishForeign Office exchanges <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persia</strong>n commentaries expose a perfidy on thepart of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, <strong>in</strong> association with the British Legation<strong>in</strong> Bushehr, the Embassy <strong>in</strong> Tehran <strong>and</strong> the bank<strong>in</strong>g authorities of the BritishcontrolledImperial Bank, that could not have been any less shameful <strong>and</strong>destructive than any possible act of venality or <strong>in</strong>competence on the partof the <strong>Qajar</strong>s. The list of malfeasance has been amply recorded elsewhere,<strong>and</strong> extended to double-deal<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> concessionary arrangements with theBakhtiari, 2 the halt<strong>in</strong>g of royalty payments for two years <strong>in</strong> contraventionof the concession’s terms, <strong>and</strong> the siphon<strong>in</strong>g of thous<strong>and</strong>s of barrels of unpaidforcrude oil to the British Admiralty at cost – actions aga<strong>in</strong>st which, with<strong>in</strong>the structure of the Great Game, <strong>Persia</strong> had few <strong>in</strong>struments with which tofight, <strong>and</strong> which cost her not only her f<strong>in</strong>ancial security, but helped to confirmthe <strong>Qajar</strong>’s dismal reputation.CONTEMPORARY PARALLELS WITHTHE QAJAR PERIODThe lessons of history are not to be drawn from a search for repetition, butrather, from the way that def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g characteristics of a place <strong>and</strong> people canaffect responses to events <strong>in</strong> similar ways across widely spaced periods oftime. For <strong>Persia</strong> under the <strong>Qajar</strong>s, its geopolitical importance <strong>and</strong> its needto protect both its borders <strong>and</strong> its resources, reflected a cont<strong>in</strong>uum that def<strong>in</strong>ed<strong>Persia</strong>n identity <strong>and</strong> <strong>Persia</strong>n foreign policy, <strong>and</strong> which cont<strong>in</strong>ues to do soeven under the country’s rubric as the Islamic Republic of Iran. For Iran,these two critical elements constitute Braudel’s “la longue durée”, that is, theslow-mov<strong>in</strong>g factors that persist throughout history, <strong>and</strong> affect the crises <strong>and</strong>choices faced whenever an important juncture is reached.In the early period of the <strong>Qajar</strong> dynasty under Fath-Ali Shah, <strong>and</strong> beforehim, under the Safavids, <strong>Persia</strong> was the dom<strong>in</strong>ant state <strong>in</strong> the region, a geopoliticalh<strong>in</strong>ge between all four sections: the divided Arab entities of the <strong>Persia</strong>nGulf, a still embryonic British India, a militarily subdued Czarist Russia <strong>and</strong>an Ottoman empire more focused on European conquest than Asian expansion.This was a period that has its parallel <strong>in</strong> the situation enjoyed bymodern Iran <strong>in</strong> the latter decade of the twentieth century, a position of dom<strong>in</strong>ancega<strong>in</strong>ed primarily because of geopolitics, as the Soviet Union collapsed<strong>and</strong> withdrew not only physically from Afghanistan <strong>and</strong> the Central Asianstates, but f<strong>in</strong>ancially from support<strong>in</strong>g Iraq <strong>and</strong> Syria. The events of 2001,

Introduction 11however, brought this Iranian dom<strong>in</strong>ance to an abrupt halt as the UnitedStates appeared to Iran’s east <strong>in</strong> Afghanistan <strong>and</strong> north <strong>in</strong> the Central Asianrepublics of Uzbekistan <strong>and</strong> K<strong>az</strong>akhstan, <strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> 2003, to Iran’s west <strong>in</strong> Iraq.Much like the situation faced by the <strong>Qajar</strong>s as the Great Game came to focusmilitary might around its periphery, so Iran faced a situation <strong>in</strong> the earlytwenty-first century, <strong>in</strong> which it was directly pressured on three sides <strong>and</strong>forced back from geopolitical dom<strong>in</strong>ance to a purely Gulf dimension.Yet, like the <strong>Qajar</strong>s, the leaders of Iran today are fac<strong>in</strong>g a period ofGreat Power rebalanc<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>in</strong>cludes several similar characteristics to thatbygone era: the conflicts around it are, for example, beyond Iran’s direct controlbut play off its critical geopolitical importance, <strong>and</strong> the rebalanc<strong>in</strong>g ofthe Great Power relationship <strong>in</strong> its region relates directly to Iran’s particularapproach to political <strong>and</strong> strategic <strong>in</strong>dependence <strong>in</strong> regard to its attemptsto ward off outside penetration. The greatest force on Iran’s several borders,the United States, is, much like imperial Brita<strong>in</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Qajar</strong> period,discover<strong>in</strong>g itself unable fully to control events on either side of Iran’s territory,the massive American military strength be<strong>in</strong>g sapped of efficacy <strong>in</strong> theface of local realities; <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stead, US power f<strong>in</strong>ds itself vulnerable <strong>in</strong> theface of the complex geopolitical l<strong>in</strong>kages <strong>and</strong> ignom<strong>in</strong>ies that characterizeregional relationships. US foreign policy towards Iran is based on an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gof the state that is astonish<strong>in</strong>gly similar to that of Brita<strong>in</strong>’s dur<strong>in</strong>gthe <strong>Qajar</strong> period <strong>and</strong> which constructed the <strong>Qajar</strong>s <strong>in</strong> terms that have theirecho <strong>in</strong> American constructions of the Islamic Republic. These <strong>in</strong>clude theview that Iran’s threat emanates from a weak government, that it is <strong>in</strong>competent<strong>in</strong> governance <strong>and</strong> shamefully corrupt, that it suffers a fundamental<strong>in</strong>ability to form a cohesive l<strong>in</strong>k with its people, that its Oriental traditionsare <strong>in</strong>compatible with modernity <strong>and</strong> that its obstreperous rhetoric cont<strong>in</strong>uouslypits one power aga<strong>in</strong>st another <strong>in</strong> delay<strong>in</strong>g tactics that promote onlyIran’s nefarious plans. Perhaps a further parallel can be drawn <strong>in</strong> the tendencyto characterize the decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g process of the current Iranianleadership aga<strong>in</strong> as fraught with irrationality, ulterior motives <strong>and</strong> lack ofpolitical vision, <strong>in</strong> other words, as overly personal <strong>in</strong> nature <strong>in</strong> contrast tothe “impersonal, rational, objective” way by which Iran’s rivals <strong>in</strong> the region<strong>and</strong> beyond are thought to come to their decisions.Not least among the difficulties faced by the US <strong>and</strong> its partners <strong>in</strong>the current crisis is the question of borders, particularly along the Shatt-alArab (although the Kurdish regions to the north, <strong>and</strong> the eastern border ofBaluchistan are not altogether immune). Despite the Algiers Agreement of1975, the southwestern border rema<strong>in</strong>s an ambiguous area of shift<strong>in</strong>g tribes,active gun-runn<strong>in</strong>g, multiple power sources <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent militias, manyof which are l<strong>in</strong>ked to the holy cities that l<strong>in</strong>e the divide between Iran <strong>and</strong>Iraq. As noted earlier, Williamson draws a similar picture as exist<strong>in</strong>g dur<strong>in</strong>gthe early n<strong>in</strong>eteenth century, suggest<strong>in</strong>g a pattern along a geopoliticaldivide of longue durée. The parallels with the later Treaty of Erzerum, <strong>and</strong>the contests it left <strong>in</strong> its wake, need not be further emphasized.

12 Roxane FarmanfarmaianIranian geopolitics is significant to another Great Power relationshipalong its borders, that of the US <strong>and</strong> Russia, which, like Brita<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Russiadur<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Qajar</strong> period, appear deeply distrustful of each other’s motives<strong>in</strong> their approach to the Iranian plateau. For Russia today, as <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Qajar</strong>past, Iran is its “near abroad”, a country with which it shares a long border<strong>and</strong> with which it has extensive trade agreements. To underst<strong>and</strong> the tensionsbetween the United States <strong>and</strong> Russia today, an analysis of the uncerta<strong>in</strong>relationship between Russia <strong>and</strong> Brita<strong>in</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Qajar</strong> period mayoffer useful <strong>in</strong>sights as, like the US today, Brita<strong>in</strong> then was the non-residentpower, its greatest engagement <strong>in</strong> the region based on economic <strong>and</strong> strategic<strong>in</strong>terests rather than geopolitical imperative. Brita<strong>in</strong>’s commitment to Indiacan be seen to have its echoes <strong>in</strong> the US commitment to the oil-rich Gulfstates, <strong>in</strong> both cases mark<strong>in</strong>g a course that conta<strong>in</strong>s with<strong>in</strong> it both a fear ofexp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g Russian <strong>in</strong>fluence though Iran <strong>in</strong>to the south, <strong>and</strong> a not-so-cloakedthreat aga<strong>in</strong>st Russian adventurism – expressed perhaps most strongly todayaga<strong>in</strong>st its support of the Iranian nuclear energy project. Iran, because of itsgeopolitical location, appears aga<strong>in</strong> at the centre of this maelstrom of powerpolitics.The issue of resources likewise f<strong>in</strong>ds thematic cont<strong>in</strong>uity. For the <strong>Qajar</strong>s,the silver basis of the currency proved by the end of their reign to be adevastat<strong>in</strong>g h<strong>in</strong>drance which severely weakened the state. For modern Iran,although oil has been <strong>in</strong> many ways a boon, it has also been a curse, expos<strong>in</strong>gthe country to the vulnerabilities of price changes on the <strong>in</strong>ternationalmarket – a situation not dissimilar to the price fluctuations of silver acentury earlier.The studies <strong>in</strong> this collection are a contribution to a deeper underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gof an era important <strong>in</strong> its own right <strong>in</strong> the progress of history. Yet, their<strong>in</strong>sights beckon toward a more cohesive approach to comprehend<strong>in</strong>g howthe present is rooted <strong>in</strong> the past, <strong>and</strong> how responses can more usefully beanalyzed <strong>in</strong> relation to circumstances, rather than specific events.Notes* Special appreciation for his <strong>in</strong>put <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>sight on this <strong>in</strong>troduction goes toProfessor George E. Joffé of the Centre of International Studies, CambridgeUniversity.1 Naval Intelligence Division of HM Admiralty, <strong>Persia</strong>: Geographical H<strong>and</strong>book Seriesfor Official Use Only, B.R. 525 (Restricted), (Oxford: Oxford University Press),September 1945, p. 291.2 Stephanie Cron<strong>in</strong>, The Politics of Debt: “The Anglo-<strong>Persia</strong>n Oil Company <strong>and</strong> theBakhtiyari Khans”, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 40, No. 4, July 2004, pp. 1–31.