Life-Cycle Management - Army Logistics University - U.S. Army

Life-Cycle Management - Army Logistics University - U.S. Army

Life-Cycle Management - Army Logistics University - U.S. Army

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

pump wear, and no<br />

measured differences<br />

in engine<br />

operating temperatures<br />

were noted,<br />

which dispelled the<br />

fears of engines<br />

overheating because<br />

of supposedly hotter<br />

burning fuels.<br />

One of the more<br />

significant and comprehensive<br />

tests of<br />

JP8 was a field demonstrationconducted<br />

at Fort Bliss,<br />

Texas, from October<br />

1988 through July<br />

1991. This field<br />

demonstration involved<br />

about 2,800<br />

diesel-powered<br />

vehicles and pieces<br />

of equipment that<br />

consumed over 4.7<br />

million gallons of<br />

JP8. The demonstration<br />

proved successful: no catastrophic failures<br />

were attributed to JP8. In fact, no major differences in<br />

procurement costs, fuel consumption, oil change intervals,<br />

or component replacements were identified when<br />

compared to historical data for the same fleet of vehicles<br />

and equipment using diesel fuel.<br />

Implementation of the SFC Since 1990<br />

When approved by the combatant commander, the<br />

primary fuel support for air and ground forces in overseas<br />

theaters will be a single, kerosene-based fuel. The<br />

SFC was first implemented in December 1989, when<br />

JP5 was used as the single fuel during Operation Just<br />

Cause in Panama.<br />

In August 1990, DOD implemented the SFC by<br />

providing Jet A1 (JP8 without its three mandatory<br />

additives) for U.S. forces in Operations Desert Shield<br />

and Desert Storm. During those operations, some Air<br />

Force units were located on bases where only JP4,<br />

which could not be used in ground vehicles and equipment,<br />

was available. Some <strong>Army</strong> units requested<br />

diesel fuel instead of JP8 because JP8 did not make<br />

acceptable smoke in the M1 Abrams’ exhaust-system<br />

smoke generators. Further compounding the problems<br />

was the lack of training of ground units, which would<br />

have reduced their initial concerns about using aviation<br />

fuels in ground vehicles and equipment. Despite<br />

these problems, the SFC was considered a success.<br />

The SFC was implemented<br />

next for<br />

combat operations in<br />

Somalia, Haiti, and<br />

the eastern Balkans<br />

with the same success<br />

that it had achieved<br />

during Operations<br />

Desert Shield and<br />

Desert Storm.<br />

Minor Problems<br />

During Operations<br />

Desert Shield and<br />

Desert Storm, certain<br />

families of engines that<br />

used fuel-lubricated,<br />

rotary-distribution,<br />

fuel-injection pumps<br />

experienced some operational<br />

problems<br />

that resulted in hotstarting<br />

difficulty and<br />

gradual loss of power.<br />

(Hot starting refers to<br />

restarting a vehicle<br />

while its engine is<br />

still hot.) Usually, the engines that experienced the<br />

most problems were the General Motors 6.2-liter and<br />

6.5-liter engines, which use the commercially manufactured<br />

Stanadyne fuel-injection pump. These<br />

engines power smaller tactical wheeled vehicles, such<br />

as CUCVs and high-mobility, multipurpose, wheeled<br />

vehicles (HMMWVs). The Stanadyne fuel-injection<br />

pump is used on a variety of other engine systems that<br />

provide power to combat support and combat service<br />

support equipment.<br />

Causes of the problems with the engines included—<br />

• Sustained operation during high temperatures.<br />

• Failure to retrofit the Stanadyne fuel-injection<br />

pump with elastomer insert drive governor weight<br />

retainer assemblies.<br />

• Improperly manufactured replacement parts.<br />

• Corrosion.<br />

• Unauthorized oils and fluids added to Jet A1 fuel.<br />

• Use of Jet A1 that did not contain corrosion<br />

inhibitor and lubrication-enhancing additives.<br />

The viscosity of the Jet A1 fuel being supplied by<br />

Saudi Arabia under a host nation support agreement<br />

was very low, as was the sulfur content, which further<br />

compounded the hot-starting problems.<br />

Ironically, none of these problems occurred during<br />

the extensive testing at Fort Bliss. In hindsight, the test<br />

at Fort Bliss used JP8, which has a higher viscosity<br />

than the Jet A1 fuel typically refined in the Middle<br />

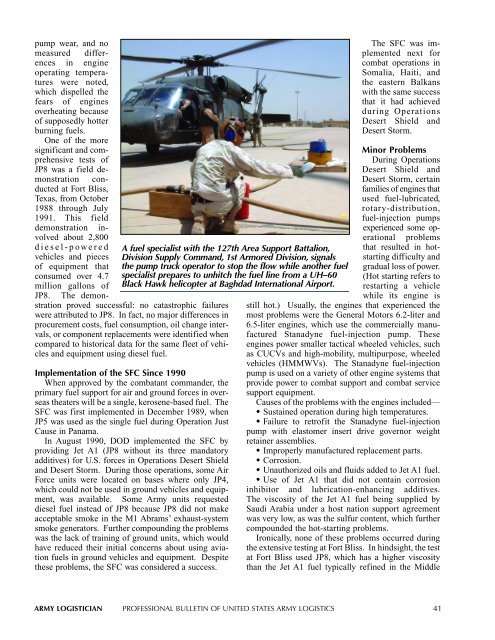

A fuel specialist with the 127th Area Support Battalion,<br />

Division Supply Command, 1st Armored Division, signals<br />

the pump truck operator to stop the flow while another fuel<br />

specialist prepares to unhitch the fuel line from a UH–60<br />

Black Hawk helicopter at Baghdad International Airport.<br />

ARMY LOGISTICIAN PROFESSIONAL BULLETIN OF UNITED STATES ARMY LOGISTICS<br />

41