Spring 2007 - Milton Academy

Spring 2007 - Milton Academy

Spring 2007 - Milton Academy

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

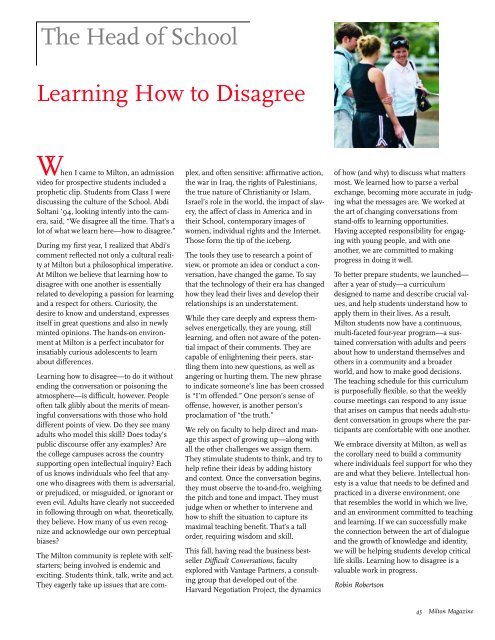

The Head of SchoolLearning How to DisagreeWhen I came to <strong>Milton</strong>, an admissionvideo for prospective students included aprophetic clip. Students from Class I werediscussing the culture of the School. AbdiSoltani ’94, looking intently into the camera,said, “We disagree all the time. That’s alot of what we learn here—how to disagree.”During my first year, I realized that Abdi’scomment reflected not only a cultural realityat <strong>Milton</strong> but a philosophical imperative.At <strong>Milton</strong> we believe that learning how todisagree with one another is essentiallyrelated to developing a passion for learningand a respect for others. Curiosity, thedesire to know and understand, expressesitself in great questions and also in newlyminted opinions. The hands-on environmentat <strong>Milton</strong> is a perfect incubator forinsatiably curious adolescents to learnabout differences.Learning how to disagree—to do it withoutending the conversation or poisoning theatmosphere—is difficult, however. Peopleoften talk glibly about the merits of meaningfulconversations with those who holddifferent points of view. Do they see manyadults who model this skill? Does today’spublic discourse offer any examples? Arethe college campuses across the countrysupporting open intellectual inquiry? Eachof us knows individuals who feel that anyonewho disagrees with them is adversarial,or prejudiced, or misguided, or ignorant oreven evil. Adults have clearly not succeededin following through on what, theoretically,they believe. How many of us even recognizeand acknowledge our own perceptualbiases?The <strong>Milton</strong> community is replete with selfstarters;being involved is endemic andexciting. Students think, talk, write and act.They eagerly take up issues that are complex,and often sensitive: affirmative action,the war in Iraq, the rights of Palestinians,the true nature of Christianity or Islam,Israel’s role in the world, the impact of slavery,the affect of class in America and intheir School, contemporary images ofwomen, individual rights and the Internet.Those form the tip of the iceberg.The tools they use to research a point ofview, or promote an idea or conduct a conversation,have changed the game. To saythat the technology of their era has changedhow they lead their lives and develop theirrelationships is an understatement.While they care deeply and express themselvesenergetically, they are young, stilllearning, and often not aware of the potentialimpact of their comments. They arecapable of enlightening their peers, startlingthem into new questions, as well asangering or hurting them. The new phraseto indicate someone’s line has been crossedis “I’m offended.” One person’s sense ofoffense, however, is another person’sproclamation of “the truth.”We rely on faculty to help direct and managethis aspect of growing up—along withall the other challenges we assign them.They stimulate students to think, and try tohelp refine their ideas by adding historyand context. Once the conversation begins,they must observe the to-and-fro, weighingthe pitch and tone and impact. They mustjudge when or whether to intervene andhow to shift the situation to capture itsmaximal teaching benefit. That’s a tallorder, requiring wisdom and skill.This fall, having read the business bestsellerDifficult Conversations, facultyexplored with Vantage Partners, a consultinggroup that developed out of theHarvard Negotiation Project, the dynamicsof how (and why) to discuss what mattersmost. We learned how to parse a verbalexchange, becoming more accurate in judgingwhat the messages are. We worked atthe art of changing conversations fromstand-offs to learning opportunities.Having accepted responsibility for engagingwith young people, and with oneanother, we are committed to makingprogress in doing it well.To better prepare students, we launched—after a year of study—a curriculumdesigned to name and describe crucial values,and help students understand how toapply them in their lives. As a result,<strong>Milton</strong> students now have a continuous,multi-faceted four-year program—a sustainedconversation with adults and peersabout how to understand themselves andothers in a community and a broaderworld, and how to make good decisions.The teaching schedule for this curriculumis purposefully flexible, so that the weeklycourse meetings can respond to any issuethat arises on campus that needs adult-studentconversation in groups where the participantsare comfortable with one another.We embrace diversity at <strong>Milton</strong>, as well asthe corollary need to build a communitywhere individuals feel support for who theyare and what they believe. Intellectual honestyis a value that needs to be defined andpracticed in a diverse environment, onethat resembles the world in which we live,and an environment committed to teachingand learning. If we can successfully makethe connection between the art of dialogueand the growth of knowledge and identity,we will be helping students develop criticallife skills. Learning how to disagree is avaluable work in progress.Robin Robertson45 <strong>Milton</strong> Magazine