Using Social Capital For Survival in War Torn Cyprus(2003)

Using Social Capital For Survival in War Torn Cyprus(2003)

Using Social Capital For Survival in War Torn Cyprus(2003)

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

________________________________________________________________________FOREWORDThe authors would like to thank Vamik Volkan, M. Tahiroglu, Jacquel<strong>in</strong>e and IsmaelTareq for comments on an earlier version of the paper. However, they alone areresponsible for all op<strong>in</strong>ions and statements.________________________________________________________________________iv

________________________________________________________________________1. IntroductionThe orig<strong>in</strong>al hypothesis beh<strong>in</strong>d this research was that <strong>in</strong> times of civil war,government services, such as education, health and welfare, become unavailable. It isthen that the family emerges as the lead<strong>in</strong>g support organization, to provide mutual aid toits members thus help<strong>in</strong>g them to survive <strong>in</strong> times of <strong>in</strong>security, trauma and deprivation.This hypothesis was to be applied <strong>in</strong> a study of Turkish Cypriot families dur<strong>in</strong>g the civilwar <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cyprus</strong> from 1963 to 1974, a subject that has received surpris<strong>in</strong>gly little attention(Volkan 1979, Oberl<strong>in</strong>g 1982). Hence the research aim was to determ<strong>in</strong>e, empirically onthe basis of fieldwork, the extent and nature of social capital (Coleman 1989, Putnam1993, Woolcock and Narayan 1999, Lesser, ed., 2000, Mehmet et al 2002) dur<strong>in</strong>g andafter the Greek-Turkish Cypriot ethnic conflict.This hypothesis had to be abandoned, or significantly modified, early <strong>in</strong> thefieldwork. The explanation had to do with the historical facts of the ethnic conflict thaterupted on Christmas Eve 1963. Turkish Cypriot survey <strong>in</strong>formants <strong>in</strong>dicated that <strong>in</strong> theaftermath of the conflict the post-colonial, bi-communal Republic <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cyprus</strong> as set upunder the 1960 Constitution ceased to exist. The Greek Cypriots, by violent means, hadousted the Turkish Cypriots from the Republic, and declared themselves as the“Government”, serv<strong>in</strong>g only themselves. The Turkish Cypriots, now concentrated <strong>in</strong>small enclaves surrounded by Greek Cypriot forces, were then placed under an economicand political embargo by this Greek Cypriot government. Under these circumstances, theCypriot Turks had to create their own government. As put by Oberl<strong>in</strong>g,“hav<strong>in</strong>g been reduced to the status of stateless persons dur<strong>in</strong>g 1963-64crisis, the Turkish Cypriots had had to organize themselves to survivethe economic blockade that followed. Thus, a patchwork governmenthad been set up. It consisted of the Vice-President of the Republic,members of the Turkish Cypriot Chamber of Commerce and a fewothers – all of whom formed a body known as the General Committee.”(Oberl<strong>in</strong>g 1982: 144)Through the period 1963/4 to 1974 ethnic conflict cont<strong>in</strong>ued <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cyprus</strong>sporadically. Dur<strong>in</strong>g this period, the creation of a Turkish Cypriot government becameessential for survival. The Turkish Cypriot government underwent stages of growth anddevelopment as cycles of ethnic conflict on the island cont<strong>in</strong>ued. Aga<strong>in</strong> it is <strong>in</strong>structive toquote from Oberl<strong>in</strong>g:“..when Grivas embarked upon his campaign to overrun Turkish Cypriotenclaves, the Turkish Cypriot leaders realized that a more efficientadm<strong>in</strong>istrative mach<strong>in</strong>ery was required. Thus, on December 28, 1967, a________________________________________________________________________1

________________________________________________________________________Provisional Turkish Cypriot Adm<strong>in</strong>istration … was established.” (Oberl<strong>in</strong>g1982: 144).Early <strong>in</strong> the conflict there was a total breakdown of adm<strong>in</strong>istration and theterm<strong>in</strong>ation of essential public services for the Turkish Cypriots. In response, a de factogovernment was set up for public adm<strong>in</strong>istration and f<strong>in</strong>ancial and food aid from Turkeybegan to arrive. These formal services were <strong>in</strong>adequate due to Greek Cypriot embargoesand limited public resources. It is these constra<strong>in</strong>ts that gave rise to social capitalamongst families, that vital element of trust and solidarity that brought beleagueredfamilies together to cooperate <strong>in</strong> the provision of collective security as well as to sharescarce food, shelter and other basic human needs. This social capital was non-formal, i.e.non-governmental, and it was supplemental to the formal distribution of public goods andservices.Therefore, the research hypothesis guid<strong>in</strong>g this paper was changed as follows:To determ<strong>in</strong>e from research on Turkish Cypriot families, the extent and type of nonformalsocial capital that can be engendered to protect aga<strong>in</strong>st the worst effects ofviolence and deprivation <strong>in</strong> times of ethnic conflict and safeguard survival. In thisalternative research agenda, the family and community of families become an importantsource of social capital, non-formal <strong>in</strong> nature, i.e. outside public services.The paper is organized <strong>in</strong> four Parts. Follow<strong>in</strong>g this Introduction, Part II willdiscuss the concept of social capital, <strong>in</strong> particular demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g its relevance <strong>in</strong> studiesof family <strong>in</strong> times of war and conflict when security and survival are uppermost <strong>in</strong> them<strong>in</strong>ds of <strong>in</strong>dividuals and families. Part III is concerned with field work designed todocument the bond<strong>in</strong>g and bridg<strong>in</strong>g forms of non-formal social capital used by theTurkish Cypriot family <strong>in</strong> times ethnic conflict dur<strong>in</strong>g 1963/4-74. The research is basedon fieldwork conducted <strong>in</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>g and summer 2002. The methodology used <strong>in</strong> thefieldwork is a 24-sample Key Informant Survey. The ma<strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of the fieldwork arealso discussed <strong>in</strong> this Part. F<strong>in</strong>ally, Part IV summarizes the general conclusions emerg<strong>in</strong>gfrom this study.2. Non-<strong>For</strong>mal <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong>: The Turkish Cypriot Family <strong>in</strong> <strong>War</strong> TimeWhat exactly is social capital? It is an abstract and elusive concept, centered onsocial relations rather than markets like human or physical capital, and therefore it is hardto def<strong>in</strong>e precisely or quantitatively. If we turn to literature for guidance, there is amultiplicity of concepts concern<strong>in</strong>g the def<strong>in</strong>ition and essential properties of socialcapital. One school of thought emphasizes social networks or “the connections that<strong>in</strong>dividual actors have with one another.” (Lesser, ed., 2000: 6). Accord<strong>in</strong>gly, it is thepositive <strong>in</strong>teraction that occurs between <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> the network that lead to theformation of social capital and its capacity for appropriation. In this context, issues such________________________________________________________________________2

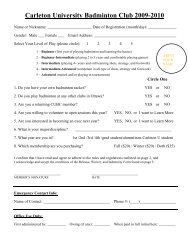

________________________________________________________________________Key Informant GroupsNo. of RespondentsAdults born before 1955 13Pile residents 3Young respondents and University students8under 30 yearsTOTAL SAMPLE 24Source: Authors’ <strong>in</strong>terviewsA pre-determ<strong>in</strong>ed Questionnaire was used <strong>in</strong> these <strong>in</strong>terviews. However, dur<strong>in</strong>gthe actual <strong>in</strong>terviews the order of questions, as well as the questions and answers, werevaried to accommodate age or unique situational traits of respondents. <strong>For</strong> <strong>in</strong>stance, <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>terviews conducted <strong>in</strong> the mixed village of Pile, located <strong>in</strong> the buffer zone under UNadm<strong>in</strong>istration and next to a British military base, respondents were asked additionalquestions to elicit <strong>in</strong>formation on liv<strong>in</strong>g conditions <strong>in</strong> Pile, generally but mistakenlyperceived as a model of Greek-Turkish co-existence 1 .Younger respondents, such as university students, represented a significant subsample.As these students grew up <strong>in</strong> a purely Turkish environment with no experience ofbi-communal liv<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>terviews with them excluded questions about socializ<strong>in</strong>g andfriendship <strong>in</strong> mixed neighborhoods, issues that were vital <strong>in</strong> the case of olderrespondents. Though ideas of their past are fundamentally those of the family elders,these younger respondents expressed their own op<strong>in</strong>ions not only about today’s islandreality, but most emphatically about future prospects.3) Analysis of F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs: Turkish Cypriot Family as the Spr<strong>in</strong>ghead of <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong>Traditionally the family unit is the most important social group <strong>in</strong> North <strong>Cyprus</strong>,more important than the <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong> terms of identity, status and <strong>in</strong>ter-personalrelationships. While <strong>in</strong>tra-family occasional conflicts may generate perverse socialcapital (e.g. conflicts over <strong>in</strong>heritance), a Turkish Cypriot family is a close, cohesive unittypically generat<strong>in</strong>g net positive social capital.As mentioned before, there are few studies of Turkish Cypriot family. Oneimportant exception is Vamik Volkan’s psychoanalytical study (1979) of war andadaptation. He notes: “The need of the <strong>in</strong>dividual to assert himself is secondary to themutual identification with<strong>in</strong> the family.” (Volkan 1979: 54). Volkan identifies several________________________________________________________________________5

________________________________________________________________________Volkan notes that similar practices can be observed <strong>in</strong> other societies. Moreover,it is also to be acknowledged that with modernization, and the pass<strong>in</strong>g of traditionalsociety, the Turkish Cypriot family is far from static, and cont<strong>in</strong>ues to be greatly affectedby historical and political circumstances. It should be noted <strong>in</strong> particular that Britishcolonialism and relations with the Greek Cypriots have had significant impacts on theTurkish Cypriot family. Thus, with the establishment of the Kemalist Republic <strong>in</strong> Turkey<strong>in</strong> 1923 and with the onset of the secularist reforms, Turkish Cypriots sought to abandonthe Islamic Sharia system of polygamy and arbitrary divorce by husbands <strong>in</strong> favor ofmodern Civil Code of family law. However, the British colonial authorities resisted thisreform. It was not until 1950’s, and after a bitter struggle, that the civil family law wasadopted (Tahiroglu 2002). Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, the same was not true <strong>in</strong> the case of seculariz<strong>in</strong>gTurkish Cypriot education. Tahiroglu <strong>in</strong>dicates that the colonial adm<strong>in</strong>istrators did not, orcould not, prevent the Turkish Cypriots who, <strong>in</strong> fact, adopted the Lat<strong>in</strong> alphabet andKemalist secular curriculum <strong>in</strong> schools even ahead of Turkey itself.As for the Greek Cypriot <strong>in</strong>fluences on Turkish Cypriot values and attitudes, thes<strong>in</strong>gle most significant impact has been the growth of Turkish Cypriot nationalism. Fromthe beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of Megali Idea (the idea of Greater Greece, <strong>in</strong>clusive of <strong>Cyprus</strong>, Istanbuland parts of Turkey) soon after the creation of Modern Greece <strong>in</strong> early 19 th century(Oberl<strong>in</strong>g 1982: Chap. II), but especially after the transfer of <strong>Cyprus</strong> from the Ottomansto the British <strong>in</strong> 1878, the Greek Cypriots, under the leadership of the Church, haveaspired to ENOSIS (union of the island with Greece). The Cypriot Turks resisted culturaland political dom<strong>in</strong>ation by Greeks. This has given rise to an extensive literature thatseeks to def<strong>in</strong>e their historical orig<strong>in</strong>s (Gazioglu 1992), to consolidate and enhance theirculture (Dogramaci et al., eds. 1996), and to analyze Greek-Turkish relations (Bahcheli1990, Volkan and Itzkowitz 1994). In recent years, there have also been some <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>gstudies <strong>in</strong> contrast by Greek Cypriots (Mavratsas <strong>in</strong> Kerides and Triantaphyllou, eds.,2001: Chap. 8).***The Turkish Cypriot family, with<strong>in</strong> the broader context of the evolv<strong>in</strong>g TurkishCypriot identity and solidarity, has been strengthened as a result of the shared trauma andstress experienced <strong>in</strong> the war period 1963/4-74. Child-parent l<strong>in</strong>ks, traditionally strong,were cemented by shared experience of sacrifice: Thus, when markets suddenly ceased toprovide food, shelter and other basic human needs, aid channels through the familybecame the means of support. Similarly, when the labor market disappeared as a sourceof <strong>in</strong>come, the family emerged as the next best alternative of <strong>in</strong>come support. Overall,survival of the Turkish Cypriot families dur<strong>in</strong>g 1963/4 – 1974 depended, <strong>in</strong> a largemeasure, on the stock of bond<strong>in</strong>g and bridg<strong>in</strong>g social capital embedded with<strong>in</strong> thecommunity. Much of this stock was non-formal especially <strong>in</strong> the early stages of the civilwar when Turkish Cypriots were, as stated by Oberl<strong>in</strong>g, became “stateless” <strong>in</strong> their own________________________________________________________________________7

________________________________________________________________________land.Below are some sketches of this experience emerg<strong>in</strong>g from the key <strong>in</strong>formant<strong>in</strong>terviews, start<strong>in</strong>g with a picture of life <strong>in</strong> a mixed village before December 1963 when<strong>in</strong>ter-communal fight<strong>in</strong>g broke out on the island on Christmas Eve (Stephens 1966,Clerides 1989).a) Life <strong>in</strong> a Mixed Village before and after December 1963 2E. was born <strong>in</strong> 1931 <strong>in</strong> the Turkish quarter of the mixed village of Istavrogonno <strong>in</strong> thePaphos District, now <strong>in</strong> South <strong>Cyprus</strong> He married M., also of the same village, <strong>in</strong> 1949.E. grew up <strong>in</strong> a Turkish Cypriot enclave surrounded by several large Greek Cypriotvillages. School<strong>in</strong>g was separated along ethnic and religious l<strong>in</strong>es, as were all other social<strong>in</strong>stitutions from cooperatives to football clubs. The couple, who both learnt good Greek,remembered only one case of <strong>in</strong>termarriage <strong>in</strong> the region: a case of elopement whichterm<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong> 1975 when Turkish Cypriots from the South were moved, en mass, to theNorth 3 ,and the Greek Cypriot wife <strong>in</strong> this marriage decided to stay beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> the South.As an adult E. became a shepherd while also engaged <strong>in</strong> mixed farm<strong>in</strong>g, grow<strong>in</strong>gwheat, barley and grapev<strong>in</strong>e on his 20-donum land. He learnt Greek <strong>in</strong> order to carry outbus<strong>in</strong>ess deal<strong>in</strong>gs. Prior to 1955, there was lots of <strong>in</strong>teraction with Greek Cypriots and heremembered play<strong>in</strong>g cards <strong>in</strong> coffee shops, attend<strong>in</strong>g wedd<strong>in</strong>gs and tak<strong>in</strong>g part <strong>in</strong> allk<strong>in</strong>ds of mixed social relations. “Kids played together <strong>in</strong> the village and there were nopolitics” E. recalled. His wife M., who learnt Greek to socialize with Greek Cypriotneighbors, had one close Greek Cypriot friend who spoke good Turkish. As late asDecember 1963, the two would meet <strong>in</strong> secret <strong>in</strong> the fields to chat and exchange news.The reason for secrecy <strong>in</strong> these meet<strong>in</strong>gs was that <strong>in</strong>ter-ethnic relations <strong>in</strong> the village hadbegun to deteriorate from 1955 onwards. On April 1, 1955 Grivas, backed byArchbishop/President Makarios, launched his EOKA campaign of violence first directedaga<strong>in</strong>st British colonialism but fundamentally represent<strong>in</strong>g the onset of revolutionarystruggle for ENOSIS to unite <strong>Cyprus</strong> with Greece.In August 1958 E. jo<strong>in</strong>ed the Turkish Cypriot resistance movement, TMT, which hadestablished a secret cell <strong>in</strong> the village. Aga<strong>in</strong>st a backdrop of EOKA violence, theTurkish Cypriots <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly feared for their security, expect<strong>in</strong>g an attack anytime. “Therope broke” at about this time when Greek Cypriot police arrested some Turkish Cypriotvillagers for gun possession. The tense climate <strong>in</strong> the village lasted until December 1963when <strong>in</strong>ter-communal fight<strong>in</strong>g on the island erupted. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the civil war period fromDecember 1963 until the Turkish military <strong>in</strong>tervention <strong>in</strong> July 1974, life <strong>in</strong> the villagewas one of siege. Families survived by shar<strong>in</strong>g food and other resources while the menshared duty as soldiers to defend themselves. Insecurity was the biggest and constantthreat: E. and M. recalled several <strong>in</strong>cidents of Greek Cypriot attacks, which were always________________________________________________________________________8

________________________________________________________________________repelled. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the entire village was relocated to the town of Akdogan <strong>in</strong> North<strong>Cyprus</strong> <strong>in</strong> 1975, the year follow<strong>in</strong>g the Turkish military <strong>in</strong>tervention.b) Student, Soldier, Bus<strong>in</strong>essmanN. is a successful bus<strong>in</strong>essman <strong>in</strong> Nicosia, active <strong>in</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess organizations and aregular participant <strong>in</strong> peace-mak<strong>in</strong>g workshops organized by Americans, Nordiccountries and other third parties sponsored by the Americans and Europeans. He wasborn <strong>in</strong> 1941 <strong>in</strong> the mixed neighborhood of Arpalik <strong>in</strong> Nicosia District. He was educated<strong>in</strong> the English School, and then at the Political Science Faculty of Ankara University. Heand his elder brother were members of the University student cont<strong>in</strong>gent that was secretlysent to Erenkoy <strong>in</strong> North-West <strong>Cyprus</strong> <strong>in</strong> 1964 to establish a military beachhead aga<strong>in</strong>stGreek and Greek Cypriot attacks <strong>in</strong> the area. N. served at Erenkoy for almost two years.It was a terrify<strong>in</strong>g experience, as they had to fight off successive rounds of attacks byGreeks. He lost his elder brother <strong>in</strong> one of these attacks. His eldest son was named afterhis lost brother both as a symbol of respect and of cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g solidarity. The surviv<strong>in</strong>gstudent soldiers were f<strong>in</strong>ally pulled out and returned to Turkey but the experience has lefta deep traumatic impact on several participants <strong>in</strong> this campaign <strong>in</strong> some cases result<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> permanent psychological damage.Surpris<strong>in</strong>gly however, N. is neither bitter nor dysfunctional as a result of hisErenkoy experience. He has become a successful bus<strong>in</strong>essman, emerged as a leader <strong>in</strong> thebus<strong>in</strong>ess community, and is an articulate voice of Greek-Turkish reconciliation based onequal partnership between two states <strong>in</strong> <strong>Cyprus</strong>, liv<strong>in</strong>g side and side <strong>in</strong> peace. Heremembers that <strong>in</strong> his childhood his grandparents, landowners <strong>in</strong> the village of Bodamya,did a lot of socializ<strong>in</strong>g with Greek clients. Prior to 1955, <strong>in</strong>ter-communal relations werenormal and peaceful, but after 1955 (when EOKA violence began) N. noticed for the firsttime that “Greeks were different” from Cypriot Turks. <strong>For</strong> the latter “ENOSIS meantleav<strong>in</strong>g one colonial rule for another.” <strong>For</strong> N. conditions became worse after theChristmas 1963 general attack by Greek militia on the Turkish Cypriot community. Hisfather, a senior police officer <strong>in</strong> the mixed Republic, <strong>in</strong> 1965 had his life threatened byhis Greek Cypriot counterparts, an event that caused him to jo<strong>in</strong> the national movement<strong>in</strong> defense of Turkish Cypriot community. This event also demonstrated for N. that thelast shred of trust was f<strong>in</strong>ally broken between the two ethnic groups on the island.c) Trust and Solidarity <strong>in</strong> <strong>Social</strong> RelationsTrust was one of the recurrent responses <strong>in</strong> the Key Informant Survey. Trust wasused consistently used <strong>in</strong> the tw<strong>in</strong> theme of (1) “broken trust” between the Greek andTurkish Cypriots <strong>in</strong> contrast to (2) <strong>in</strong>tra-group trust amongst Turkish Cypriots under acommon external threat to survival. Typical of these sentiments was the case of A. Agedover 60, A. was born <strong>in</strong> Turkish Cypriot village of Yayla, near the Greek Cypriot town of________________________________________________________________________9

________________________________________________________________________Polis <strong>in</strong> the North-West of the island. Her family was relatively well-to-do withsignificant ownership of land and real estate <strong>in</strong> the village. In 1952 when she married, shemoved to Kucuk Kaymakli, the scene of some of the heaviest fight<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> December 1963.She and her family became refugees. While none of her parents or sibl<strong>in</strong>gs died <strong>in</strong> thefight<strong>in</strong>g, she lost a nephew. As a result of the ethnic divide along the Green L<strong>in</strong>e whichthe UN then created, A.’s family suffered a big f<strong>in</strong>ancial loss <strong>in</strong> the form of some 100donums of prime land, water rights, and several houses left beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>in</strong> Yayla after theywere removed to the North.The follow<strong>in</strong>g exchange took place dur<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>terview with her, first withregard to <strong>in</strong>ter-ethnic trust, and secondly <strong>in</strong>tra-group trust with<strong>in</strong> Turkish Cypriots:d) On <strong>in</strong>ter-ethnic trust:Question: When you th<strong>in</strong>k of Greek Cypriots, what are your first feel<strong>in</strong>gs?Anwer: Hate because I suffered a lot.Question: Would you be will<strong>in</strong>g to live <strong>in</strong> a mixed village aga<strong>in</strong>?Answer: No, not after all the past hostility. Not even for economic reasons. Peaceof m<strong>in</strong>d is more important.Question: How many cases of Greek and Turkish Cypriot cases of <strong>in</strong>ter-marriagedo you know? Answer: Are you crazy? None.e) On <strong>in</strong>tra-group Trust:When asked to rank trust <strong>in</strong> an ascend<strong>in</strong>g order with<strong>in</strong> the Turkish Cypriotcommunity itself, A. stated that she trusted first her parents, grandparents second,brothers and sisters third, extended family members next, and neighbor last. By trust <strong>in</strong>this case what A. meant was that if her parents needed help, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>ancial aid, whowould they turn to? She stated that unlike family members, help provided by neighborswould always have to be repaid, <strong>in</strong> contrast to reciprocal exchanges <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tra-familyobligations.f) Family Investment <strong>in</strong> EducationE. is a retired school teacher, born <strong>in</strong> 1944 <strong>in</strong> the mixed village of M<strong>in</strong>arelikoy, ashort distance north-west of Nicosia on the slopes of Five F<strong>in</strong>ger Mounta<strong>in</strong>s. Althoughnever a refugee, E. was forced to evacuate his village <strong>in</strong> January 1964, along with otherTurkish Cypriot villagers, at the outset of ethnic violence. He relocated to Meric, anothervillage not far from his, <strong>in</strong> the Turkish Cypriot controlled area and became a commander<strong>in</strong> the Turkish Cypriot militia hav<strong>in</strong>g taken part <strong>in</strong> several military operations. The years________________________________________________________________________10

________________________________________________________________________from 1964-74 were a period of hardship: “no food, bread, just bullets and a nationalcause” he recalls. E’s. wife, A*., is also a school teacher, and they have two daughters.N., the eldest recently qualified as a neurologist after some 10 years of medical studies <strong>in</strong>Ukra<strong>in</strong>e, while her younger sister, also highly educated, is a fitness <strong>in</strong>structor runn<strong>in</strong>g herown small bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong> Istanbul.The E.-A*. family has modest means, now liv<strong>in</strong>g on pension. The education oftheir two daughters is a good demonstration of the Turkish Cypriot households’ toppriority placed on education as a jo<strong>in</strong>t family <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> children and as a pathway tofamily-sponsored career development. Families cut down on other expenses, often sellland and real estate, <strong>in</strong> order to <strong>in</strong>vest <strong>in</strong> children’s school<strong>in</strong>g. Even though education <strong>in</strong>North <strong>Cyprus</strong> is free and compulsory from primary to secondary level, families spendlarge amounts on private pre-school and after-hours coach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> order to prepare theirchildren for competitive exam<strong>in</strong>ations.N., now 30, is aware of her families sacrifice and <strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> her and hercareer; she lives at home with her parents even though she now has a secure governmentjob and a professional practice. The bonds between daughter and parent <strong>in</strong> the E.-A*.family is liv<strong>in</strong>g testimony to the social capital formation <strong>in</strong> Turkish Cypriot families.g) The Special Case of PileInterviews with three families <strong>in</strong> the unique village of Pile <strong>in</strong> the buffer zone (seeabove) strongly re<strong>in</strong>forced A.’s views and attitudes (see above). Pile has the uniquedist<strong>in</strong>ction of be<strong>in</strong>g the only bi-communal village with mixed neighborhoods. In theory,it is adm<strong>in</strong>istered cooperatively by Greek and Turkish Cypriots mayors under the aegis ofthe UN garrison there.X was born <strong>in</strong> Pile <strong>in</strong> 1944, subsequently migrated to England where he madesome money and returned to his village <strong>in</strong> 1988, built a house and earns his liv<strong>in</strong>g do<strong>in</strong>godd jobs <strong>in</strong> the service sector. Thanks to his fluency <strong>in</strong> English, he has participated <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ter-communal projects, sponsored by the United Nations such as street improvement. Xhas stated that life <strong>in</strong> Pile is very <strong>in</strong>secure because the Greek and Turkish Cypriotneighbors do not trust each other whatsoever. Even a small <strong>in</strong>cident, such a park<strong>in</strong>gviolation, is capable of br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g to a halt the social and economic life of the village thatshares physical space but <strong>in</strong> no sense shares <strong>in</strong>ter-communal solidarity.M., another respondent from Pile, elaborated on the economic and trade embargounder which the Turkish Cypriot families <strong>in</strong> the village have to live. Some 10 years agoeconomic welfare of these families was much better because there were some 43 thriv<strong>in</strong>gTurkish Cypriot shops, restaurants and bus<strong>in</strong>esses, sell<strong>in</strong>g goods and services fromTurkey and North <strong>Cyprus</strong> at competitive prices to tourists from the South. Then, theGreek Cypriot authorities suddenly term<strong>in</strong>ated the tourism from the South, upon________________________________________________________________________11

________________________________________________________________________compla<strong>in</strong>ts from traders and hotel owners <strong>in</strong> the South. The Greek Cypriot police<strong>in</strong>stalled a Police checkpo<strong>in</strong>t on their side of the border to prevent shoppers import<strong>in</strong>gTurkish goods. Overnight Turkish Cypriot economy of Pile took a nose-dive. As M. putit: “Greek Cypriots only want Turkish Cypriots work<strong>in</strong>g as (cheap) laborers.”O*, M.’s brother and neighbor <strong>in</strong> Pile, stressed that although this is a mixedvillage, there is no cross-ethnic socializ<strong>in</strong>g, and that the atmosphere is always tense,ready to explode. He shares his brother’s perception that “the heart of the (<strong>Cyprus</strong>problem) is that the Greeks swore to make the island their own.”The picture that emerged from <strong>in</strong>terviews <strong>in</strong> Pile was most surpris<strong>in</strong>g. The<strong>in</strong>formants there demonstrated the greatest <strong>in</strong>security and pessimism of all <strong>in</strong>terviewees.In actuality it is by no means the model of a future reunited <strong>Cyprus</strong>, as some have argued.In the light of our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from Pile and elsewhere, we now exam<strong>in</strong>e theimportant subject of security and the role of family as the provider of protection <strong>in</strong> timesof war.h) Security as <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong>In the <strong>Cyprus</strong> civil war period between 1963/4 and 1974 there was no <strong>in</strong>ter-communalpolice and security forces. Movement of persons on the island was dangerous because ofthe absence of rule of law, and constant threat of ethnic fight<strong>in</strong>g. Arbitrary searches bymilitia, arrests and disappearance of persons on highways were common occurrences. Inthis environment the solidarity of Turkish Cypriot families emerged as the primarysource of protection. They organized defensive networks, tak<strong>in</strong>g arms <strong>in</strong> defense of lifeand property. Households banded together <strong>in</strong> voluntary and ad hoc networks to becomedefenders of homes and villages under attack. The social solidarity displayed hereconfirmed exist<strong>in</strong>g social capital and <strong>in</strong>creased it <strong>in</strong> the process of defense cooperation.In these defensive roles, a fledgl<strong>in</strong>g Turkish Cypriot militia and the underground TMTsupplemented voluntary family soldiers. The <strong>in</strong>formal security and protection emerged asa vital form of social capital. To this day, some 40 years later, family security and peaceof m<strong>in</strong>d constitute the foremost need <strong>in</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>ds of Turkish Cypriots. This security needis so compell<strong>in</strong>g it shapes visions of discussions about the future of the island.The emotional scars of the Cypriot conflict are also reflected <strong>in</strong> the respondents’obsession with security. Volkan (1979: 81) notes that “it would appear that a fifth ofthose liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> enclaves were refugees, survivors of overwhelm<strong>in</strong>g stress and change,victims of massive psychic trauma of expulsion from their homes, the loss of many dearto them, and constant fear. Statistics verify the degree of uproot<strong>in</strong>g and change theysuffered.” It should be noted that very few of these survivors received professionalcounsel<strong>in</strong>g due lack of such professionals. It was up to the families and communitymembers to help each other emotionally as well as materially.________________________________________________________________________12

________________________________________________________________________i) Food, Shelter and ServicesWith the imposition of an economic embargo by the Makarios regime <strong>in</strong> early1964, Turkish Cypriots were cut off from normal trade and market networks. Civilservants lost their pay and position. Their economic livelihood, as well as that of bicommunalbus<strong>in</strong>ess and trade people, was suddenly term<strong>in</strong>ated.The civil war created refugees as exemplified by the case of A. Thus, familieswere obliged to share food, shelter and other basic needs with refugees and displacedpersons 4 . In time, the Turkish Red Crescent began to supply food aid from Turkey andgradually this supply was regularized through official Turkish Cypriot authorities, ma<strong>in</strong>lymilitary channels. Similarly, schools and hospitals resumed and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed operationsunder difficult circumstances. Transportation <strong>in</strong> the island was always dangerous right upto the Turkish military <strong>in</strong>tervention <strong>in</strong> the summer of 1974. Many families reportedmiss<strong>in</strong>g relatives due to arbitrary arrests or executions dur<strong>in</strong>g this period.j) Identity TransformationIn the period 1963/4-74, a new community identity emerged out of the commonthreat fac<strong>in</strong>g the Turkish Cypriot. It is dur<strong>in</strong>g this period that “Divided <strong>Cyprus</strong>”(Stavr<strong>in</strong>ides 1975: 109) became a reality, and two national identities evolved on eitherside of the UN Green L<strong>in</strong>e, Cypriot Turks and Cypriot Greeks 5 . The former were forciblyherded <strong>in</strong>to enclaves add<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> toto to about 3% of the island’s territory. <strong>For</strong> over adecade, the community was cut off and isolated from the rest of the world. No one wasexempt from the loss of liberty and freedom, economic hardship and denial of humanrights. From that time on, for island Turks the Cypriot identity is utterly dead, hav<strong>in</strong>gbeen replaced by a national Turkish Cypriot identity. In our survey we have not found asurvivor of this generation who will forget the past enough to consent to live with GreekCypriots ever aga<strong>in</strong> under one government.The younger generation of Turkish Cypriots, born after 1974 have no directexperience of these tragic memories, although they are relived through parentalrem<strong>in</strong>isc<strong>in</strong>g. Young people generally share their parents’ and elders’ mistrust of theGreek Cypriots, and though there is support for reunification of the island, thepreponderant expectation is that of physical separation, or two ethnic identities liv<strong>in</strong>gside by side. It is fair to say that the youth’s political vision of the future tends to be lessnationalistic, and generally more pessimistic due, largely, to economic factors such ashigh unemployment among the young.Typical of this younger generation is H. who was born <strong>in</strong> 1977, is currently agraduate student at university, and has never met a Greek Cypriot. He is worried about________________________________________________________________________13

________________________________________________________________________employment prospects for young persons. He is especially worried about the highunemployment rate among the youth, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g university graduates. H. is alsoconcerned about the large military presence <strong>in</strong> the North. He is rather pessimistic aboutfuture prospects, believes a lot of young Turkish Cypriots will leave the island whilemore settlers will arrive from Turkey. He expects that, for strategic reasons Turkey willnever give up <strong>Cyprus</strong>, and North <strong>Cyprus</strong> will ultimately be united with Turkey, which isnot, <strong>in</strong> his op<strong>in</strong>ion, the best solution.A radically different vision is reflected by A**, a female university student born<strong>in</strong> 1982. Her grandfather spoke Greek and recalls hav<strong>in</strong>g Greek friends with whom heworked or met <strong>in</strong> coffee shops shar<strong>in</strong>g a table. A** is also pessimistic, fear<strong>in</strong>g that<strong>Cyprus</strong> will ultimately be re-united because Greek Cypriots have economic power. “Theywill kill us slowly, not by war, but through their economic power. If they like this area,they won’t let us live here.”4) ConclusionTwo major conclusions emerge from the empirical results of this study of theexperience of the Turkish Cypriot family <strong>in</strong> the war time period 1963/4 - 1974. First isthe vital role which non-formal social capital played <strong>in</strong> the survival of the communitywhen it was under violent attack by the numerically superior Greek Cypriots <strong>in</strong> pursuit ofpolitical aims. Although resources and aid from formal government channelssupplemented it, <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itial period of the civil war non-formal social capital wasdecisive for survival. The Turkish Cypriot family proved critical for ethnic survival.Family social capital nourished a new national identity amongst Turkish Cypriots, f<strong>in</strong>allylead<strong>in</strong>g to the establishment <strong>in</strong> 1983 of the Turkish Republic of Northern <strong>Cyprus</strong>.Secondly, protection and security is a critical cause and effect of non-formalsocial capital <strong>in</strong> times of ethnic conflict. Turkish Cypriot families <strong>in</strong> villages and urbanmahalles (quarters), when suddenly confronted with a Greek Cypriot onslaught onChristmas Eve 1963, voluntarily took up arms <strong>in</strong> defense of their families and theircommunities. As noted above, the bond<strong>in</strong>g of these family soldiers created a largelyvolunteer army utiliz<strong>in</strong>g non-formal social capital. A fundamental theme reiteratedconstantly <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terviews was the need for security and peace of m<strong>in</strong>d. In wartime thefundamental need for security was realized through social capital epitomized by trust andsocial solidarity and manifested by mutual cooperation <strong>in</strong> defense. Equally emphatically,for the future security was stressed <strong>in</strong> order to avoid the trauma and tragic experiences ofthe past. Vamik observers 6 : “Dur<strong>in</strong>g 1963-74 when state-provided security was lost, theCypriot Turks also symbolically created a condition <strong>in</strong> order to feel secure: Theydisplaced their own images to caged birds (parakeets) and then took care of the birds(hundreds and hundreds of them <strong>in</strong> houses, coffee shops and stores). As long as the birdssang and rema<strong>in</strong>ed fertile, the Cypriot Turks could ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> their illusion of security.”________________________________________________________________________14

________________________________________________________________________The caged birds still exist, though <strong>in</strong> much fewer numbers. This can be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as acont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g expression of hope and optimism.In sum, the conclusion emerg<strong>in</strong>g from this study is reconfirmation that socialcapital, especially non-formal, is a critical resource, essential for group survival. Ourf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs suggest that <strong>in</strong> groups such as the Turkish Cypriots with high levels of socialcapital (i.e. manifested <strong>in</strong> group solidarity, mutual trust and read<strong>in</strong>ess of families tocooperate <strong>in</strong> war and peace), survival is more likely, and hope is high. The corollaryimplied is that for those groups with low levels of social capital (i.e. when families aredisunited and there is no trust <strong>in</strong> relationships), survival <strong>in</strong> the face of external threat ishighly doubtful.In war and conflict all groups suffer loss, trauma and experience the need to heal. Thispaper focussed as it is on Turkish Cypriots, <strong>in</strong> no way is <strong>in</strong>tended to m<strong>in</strong>imize the GreekCypriot suffer<strong>in</strong>g and need to heal.________________________________________________________________________15

________________________________________________________________________ENDNOTES1 See, for example, the website: www.cs.ucy.ac.cy/~ank/pyla.html where it is claimed that Pile (Pyla <strong>in</strong>Greek) “is the only place where Greek and Turkish Cypriots live together. They have been liv<strong>in</strong>gpeacefully for as long as our memory can account.” Accessed on 8/11/2002 2.23pm2 Respondents will be identified only by a letter to protect <strong>in</strong>dividual identity. * signifies differentiation.3 This was part of a population exchange agreement between Turkish and Greek Cypriot leadership,negotiated under UN auspices, whereby Greek Cypriots moved to the South.4 Turkish Cypriots abroad, especially <strong>in</strong> England and Australia, also provided significant f<strong>in</strong>ancial supporttypically through family networks.5 Vamik Volkan, <strong>in</strong> a personal communication, has cogently <strong>in</strong>quired that “s<strong>in</strong>ce their primary identityrefers to their ethnicity” might the islanders be labeled as either Cypriot Turks or Cypriot Greeks? Weagree with Volkan, but s<strong>in</strong>ce the conventional usage <strong>in</strong> the literature is Turkish or Greek Cypriot, wehave reta<strong>in</strong>ed this usage.6 In private communication.________________________________________________________________________16

________________________________________________________________________BIBLIOGRAPHYT. Bahcheli, 1990, Greek-Turkish Relations S<strong>in</strong>ce 1955, Westview Press, Boulder,ColoradoG. Clerides, 1989, <strong>Cyprus</strong>: My Deposition, vol. 1, Alithia Publish<strong>in</strong>g, NicosiaJ.S. Coleman, 1988, “<strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Creation of Human <strong>Capital</strong>” repr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong>Lesser, op. cit., pp. 17 - 42E. Dogramaci, et al, editors, 1996, Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs of the First International Congress onCypriot Studies, Eastern Mediterranean University, GazimagosaF. Fukuyama, 1995, Trust: The <strong>Social</strong> Virtue and the Creation of Prosperity, Free Press,New YorkA. Gazioglu, 1990, The Turks of <strong>Cyprus</strong>, A Prov<strong>in</strong>ce of the Ottoman Empire, K. Rustemand Brother, LondonD. Keridis and D. Triantaphyllou, eds, 2001, Greek-Turkish Relations <strong>in</strong> the Age ofGlobalization, Vol. 1, Brassy’s Inc., Herndon, Virg<strong>in</strong>iaK. Kumar, 1993, Rapid Appraisal Methods, World Bank, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C.E.L. Lesser, ed., 2000, Knowledge and <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong>, Resources for the KnowledgeBased Economy, Butterworth He<strong>in</strong>emann, BostonC. Mavratsas, 2001, “Greek Cypriot Identity and Conflict<strong>in</strong>g Interpretations of the<strong>Cyprus</strong> Problem” <strong>in</strong> Kerides and TriantaphyllouO. Mehmet, M. Tahiroglu, E. Lee, 2002, “<strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong> <strong>For</strong>mation <strong>in</strong> Large-ScaleDevelopment Projects” Canadian Journal of Development Studies, Vol. XXII, No.2, pp.335-357P. Oberl<strong>in</strong>g, 1982, The Road to Bellapais, the Turkish Cypriot Exodus to Northern<strong>Cyprus</strong>, Columbia University Press, New YorkA. Portes, 1998, “<strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong>: Its Orig<strong>in</strong>s and Applications <strong>in</strong> Modern Sociology”repr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> Lesser, op. cit., pp. 43-68R. Putnam, 1993, “The Prosperous Community: <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong> and Public Life” TheAmerican Prospect, Vol. 13, pp. 35-42______________________________________________________________________17

________________________________________________________________________-----------, 1993a, Mak<strong>in</strong>g Democracy Work: Civic Traditions <strong>in</strong> Modern Italy, Pr<strong>in</strong>cetonUniversity Press, Pr<strong>in</strong>ceton NJ-----------, 1995, “Bowl<strong>in</strong>g alone: America’s decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g social capital” Journal ofDemocracy, Vol. 6, pp. 65-78G. Ranis, F. Stewart and A. Ramirez, 2000, “Economic Growth and HumanDevelopment” World Development, Vol. 28, No. 2M. Rubio, 1997, “Perverse <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong>: Some Evidence from Colombia” Journal ofEconomic Issues, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 805-816Z. Stavr<strong>in</strong>ides, 1975, The <strong>Cyprus</strong> Conflict, National Identity and Statehood, NicosiaR. Stephens, 1966, <strong>Cyprus</strong>, A Place of Arms, Pall Mall Press, LondonM. Tahiroglu, 2002, “Kemalist Reforms <strong>in</strong> Colonial <strong>Cyprus</strong>” Paper presented to theConference on International Terrorism: Turkish Model for Civil Society <strong>in</strong> IslamicCountries, Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada, March 30V. Volkan, 1979, <strong>Cyprus</strong> – <strong>War</strong> and Adaptation, a Psychoanalytical History of TwoEthnic Groups <strong>in</strong> Conflict, University Press of Virg<strong>in</strong>ia, CharlottesvilleV.Volkan and N. Itzkowitz, 1994, Turks and Greeks, Neighbours <strong>in</strong> Conflict, EothenPress, Hunt<strong>in</strong>gdon, CambridgeshireM. Woolcock and D. Narayan, 2000, “<strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong>: Implications for DevelopmentTheory, Research and Policy” The World Bank Research Observer, Vol. 15, No. 2,August______________________________________________________________________18

________________________________________________________________________ABOUT THE AUTHORKaren A. Mehmet is an Assistant Lecturer <strong>in</strong> the Department of InternationalRelations at the Eastern Mediterranean University <strong>in</strong> Gazimagosa, Turkish Republic ofNorthern <strong>Cyprus</strong>.Ozay Mehmet is a Professor of International Affairs at Carleton University,Ottawa, Canada and Visit<strong>in</strong>g Professor of Economics, EMU.______________________________________________________________________19

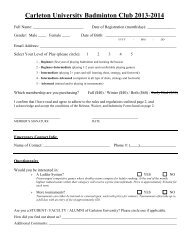

________________________________________________________________________LIST OF OCCASIONAL PAPERS1) Aliya and the Demographic Balance <strong>in</strong> Israel and the Occupied TerritoriesJames W. Moore2) A New Germany <strong>in</strong> a New EuropeJohn Halstead3) Does the Blue Helmut Fit? The Canadian <strong>For</strong>ces and Peacekeep<strong>in</strong>gIan Malcolm4) Yugoslavia - What Went Wrong?John M. Fraser5) The Orig<strong>in</strong>s and Future Demise of the Democratic People’s Republic of KoreaCharles K. Armstrong6) Contest<strong>in</strong>g an Essential Concept: Dilemmas <strong>in</strong> Contemporary Security DiscourseSimon Dalby7) Ethnic Conflict and Third Party Intervention: Risk<strong>in</strong>ess, Rationality andCommitmentDavid Carment, Dane Rowlands and Patrick James8) Conflict Prevention and Internal Conflict: Theory and Policy, A WorkshopSummary9) David Mitrany, the Functional Approach and International Conflict MangementLucian Ashworth and David Long10) Deal<strong>in</strong>g with Domestic Economic Instability: U.S. <strong>For</strong>eign Policy and the RallyEffect, 1948-1994Athanasios Hristoulas11) Modell<strong>in</strong>g Multilateral Intervention <strong>in</strong> Ethnic Conflict: A Game TheoreticApproachDavid Carment and Dane Rowlands12) The Interstate Dimensions of Secession and Irredenta: A Crisis-Based ApproachDavid Carment13) The Functional Approach, Organization Theory and Conflict ResolutionCraig N. Murphy______________________________________________________________________20

________________________________________________________________________14) <strong>Us<strong>in</strong>g</strong> a Culturally-Specific Process of Mediation and Dispute Resolution toPromote International SecurityRoger Hill15) Explor<strong>in</strong>g Canada’s Options on ‘Global’ IssuesEvan H. Potter and David Carment16) Canadian <strong>For</strong>eign Policy: From Internationalism to Isolationism?Jean-François Rioux and Rob<strong>in</strong> Hay17) Mak<strong>in</strong>g the Impossible Possible: The PLA’s Cross-Strait Operations <strong>in</strong> the 21 stCenturyJianxiang Bi18) Water Balances <strong>in</strong> the Eastern Mediterranean: A Workshop SummaryOzay Mehmet19) Conditions of Influence: A Canadian Case Study <strong>in</strong> the Diplomacy of InterventionJohn B. Hay20) Information <strong>War</strong>fare: Media-Military Relations <strong>in</strong> CanadaMichael Croft, Sharon Hobson, and Dean Oliver21) Twist<strong>in</strong>g Arms and Flex<strong>in</strong>g Muscles: Perspectives on Military <strong>For</strong>ce,Humanitarian Intervention and Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g – Report on a WorkshopNatalie Mychajlyszyn22) Canada’s Communication Security Establishment: From Cold <strong>War</strong> toGlobalizationMart<strong>in</strong> Rudner23) From Rhetoric to Policy: Towards Workable Conflict Prevention at the Regionaland Global Level – Report on a WorkshopDavid Carment, Abdul- Rasheed Draman and Albrecht Schnabel24) Intelligence and Information Superiority <strong>in</strong> the Future of Canadian DefencePolicyMart<strong>in</strong> Rudner25) The Future of the Canadian Armed <strong>For</strong>ces – Report on a WorkshopNatalie Mychajlyszyn26) Manag<strong>in</strong>g Global Chaos <strong>in</strong> the West African Sub-Region: Assess<strong>in</strong>g the Role ofECOMOG <strong>in</strong> Liberia______________________________________________________________________21

________________________________________________________________________Abdul-Rasheed Draman and David Carment27) Russia’s Policies and Military Actions Towards Tajikistan: Are there Lessons and<strong>War</strong>n<strong>in</strong>gs for America’s Involvement <strong>in</strong> Afghanistan?Nicole J. Jackson28) Family <strong>in</strong> <strong>War</strong> and Conflict: <strong>Us<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Capital</strong> for <strong>Survival</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>War</strong> <strong>Torn</strong><strong>Cyprus</strong>Karen A. Mehmet and Ozay MehmetOrder<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation:Please send a cheque or money order for $12 to (made out to The NormanPaterson School of International Affairs) to Vivian Cumm<strong>in</strong>s, NPSIA, CarletonUniversity, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, ON, K1S 5B6. If the item is to bepicked up <strong>in</strong> person, the cost is $10.00______________________________________________________________________22