The State of Basic Education in Pakistan - Sustainable Development ...

The State of Basic Education in Pakistan - Sustainable Development ...

The State of Basic Education in Pakistan - Sustainable Development ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong>:A Qualitative, Comparative InstitutionalAnalysisShahrukh Rafi Khan, Sajid Kazmi and Za<strong>in</strong>ab LatifWork<strong>in</strong>g Paper Series # 471999

All rights reserved. No part <strong>of</strong> this paper may be reproduced or transmitted <strong>in</strong> any form or by any means,electronic or mechanical, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g photocopy<strong>in</strong>g, record<strong>in</strong>g or <strong>in</strong>formation storage and retrieval system,without prior written permission <strong>of</strong> the publisher.A publication <strong>of</strong> the Susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>Development</strong> Policy Institute (SDPI).<strong>The</strong> op<strong>in</strong>ions expressed <strong>in</strong> the papers are solely those <strong>of</strong> the authors, and publish<strong>in</strong>g them does not <strong>in</strong> anyway constitute an endorsement <strong>of</strong> the op<strong>in</strong>ion by the SDPI.Susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>Development</strong> Policy Institute is an <strong>in</strong>dependent, non-pr<strong>of</strong>it research <strong>in</strong>stitute on susta<strong>in</strong>abledevelopment.WP- 047- 002- 095- 1999- 046© 1999 by the Susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>Development</strong> Policy InstituteMail<strong>in</strong>g Address: PO Box 2342, Islamabad, <strong>Pakistan</strong>.Telephone ++ (92-51) 278134, 278136, 277146, 270674-76Fax ++(92-51) 278135, URL:www.sdpi.org

Table <strong>of</strong> ContentsAbstract .................................................................................................................1Introduction ...........................................................................................................1Research Design, Sampl<strong>in</strong>g and Research Method..............................................2Conceptual Framework .........................................................................................3Field Report Evaluation .........................................................................................4Reform<strong>in</strong>g Government <strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> ............................................................15Conclud<strong>in</strong>g Remarks...........................................................................................16References..........................................................................................................19Appendixes .........................................................................................................20

<strong>The</strong> Susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>Development</strong> Policy Institute is an <strong>in</strong>dependent, non-pr<strong>of</strong>it, non-government policyresearch <strong>in</strong>stitute, meant to provide expert advice to the government (at all levels), public <strong>in</strong>terest andpolitical organizations, and the mass media. It is adm<strong>in</strong>istered by an <strong>in</strong>dependent Board <strong>of</strong> Governors.Board <strong>of</strong> Governors:Dr. Amir MuhammadChairman <strong>of</strong> the BoardMr. Hameed Haroon<strong>Pakistan</strong> Herald Publications (Pvt.) LimitedMr. Javed JabbarMNJ Communications (Pvt.) LimitedMr. Irtiza Husa<strong>in</strong>Director, <strong>Pakistan</strong> Petroleum LtdMs. Khawar MumtazShirkat GahMr. Shams ul MulkFormer Chairman, WAPDADr. Abdul Aleem ChaudhryDirector, Punjab Wildlife Research CentreMr. Malik Muhammad Saeed KhanMember, Plann<strong>in</strong>g CommissionMr. Mohammad RafiqHead <strong>of</strong> Programme, IUCN/<strong>Pakistan</strong>Dr. Zeba A. SatharDeputy Resident Representative, Population CouncilMs. Shahnaz Wazir Ali<strong>Education</strong> Specialist, MSUDr Shahrukh Rafi KhanExecutive Director, SDPIUnder the Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper Series, the SDPI publishes research papers written either by the regular staff <strong>of</strong>the Institute or affiliated researchers. <strong>The</strong>se papers present prelim<strong>in</strong>ary research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs either directlyrelated to susta<strong>in</strong>able development or connected with governance, policy–mak<strong>in</strong>g and other social scienceissues which affect susta<strong>in</strong>able and just development. <strong>The</strong>se tentative f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are meant to stimulatediscussion and critical comment.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong>:A Qualitative, Comparative Institutional Analysis 1Shahrukh Rafi Khan, Sajid Kazmi and Za<strong>in</strong>ab LatifAbstract<strong>The</strong> objective <strong>of</strong> the paper is to suggest ways to make government (by far the largest provider) rural primaryschool<strong>in</strong>g delivery more effective. We compared the <strong>in</strong>stitutional effectiveness <strong>of</strong> rural primary school<strong>in</strong>gdelivery <strong>of</strong> the government with the NGO and private sectors. Our ma<strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are first that the NGOschools were the most successful and second, that “good management” is the key <strong>in</strong>gredient for soundschool<strong>in</strong>g. Further, if mean<strong>in</strong>gful “participation” is to be achieved <strong>in</strong> government schools, the powerrelations <strong>of</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istrators, teachers and parents have to be changed.I. Introduction<strong>The</strong> objective <strong>of</strong> this research was to suggest ways to make government (by far the largest provider) ruralprimary school<strong>in</strong>g delivery more effective. We compared the <strong>in</strong>stitutional effectiveness <strong>of</strong> rural primaryschool<strong>in</strong>g delivery <strong>of</strong> the government with the NGO and private sectors. We identified processes push<strong>in</strong>g forimprovements <strong>in</strong> the NGO and private sectors and those result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> obvious failures <strong>in</strong> the governmentsectors. Our focus was on operational lessons derived from the NGO and private sector delivery that couldmake the government sector more effective.It is <strong>of</strong>ten stated that NGOs are more effective <strong>in</strong> the delivery <strong>of</strong> services than the government and, <strong>in</strong>deed, ourfield observations show that this was the case <strong>in</strong> the delivery <strong>of</strong> basic education. A critical research issue iswhether the community participation <strong>in</strong>duced or harnessed by development NGOs produces a higher qualityproduct and susta<strong>in</strong>able service delivery at a competitive price or are there other forces at play.Not much is known about rural private sector school<strong>in</strong>g. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this is a rapidlygrow<strong>in</strong>g sector. Some assert that such schools cheat gullible rural folk with a smatter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> English on thesyllabus and the status symbols represented by private sector uniforms. Others swear by the dedication <strong>of</strong>private sector teachers. Either way, it was also time to more systematically assess the contribution <strong>of</strong> suchschools, their potential for growth, the lessons derived from their practice and the social implications <strong>of</strong> theirpresence.In section II, we describe our research design, sampl<strong>in</strong>g and research method. In section III, we describe theconceptual framework, <strong>in</strong> section IV, we presents qualitative results primarily based on field evaluations, <strong>in</strong>section V we present recommendations for public sector school<strong>in</strong>g reform and we end with a conclud<strong>in</strong>gsection.1 Thanks are due to <strong>The</strong> Asia Foundation, <strong>Pakistan</strong> for support<strong>in</strong>g this research. Thanks are also due to HarisGazdar for useful comments.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong>: A Qualitative, Comparative Institutional AnalysisII.Research design, sampl<strong>in</strong>g and research methodData for the study was collected through extensive fieldwork carried out <strong>in</strong> the Punjab, S<strong>in</strong>dh,Balochistan, the NWFP and the Northern Areas between September and December 1999. To ensurethat we were compar<strong>in</strong>g the same level <strong>of</strong> school<strong>in</strong>g across NGO, private and government schools,many <strong>of</strong> the listed NGO schools were excluded s<strong>in</strong>ce they ran <strong>in</strong>formal schools while the governmentand private sector schools are mostly formal. Our <strong>in</strong>itial focus was on NGOs that ran a multipleschool program, s<strong>in</strong>ce they were the more important players <strong>in</strong> the provision <strong>of</strong> NGO school<strong>in</strong>g.We started with a Society for the Advancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>Education</strong> (SAHE) directory <strong>of</strong> NGOs <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong>education. 2 We soon realized this was not exhaustive, s<strong>in</strong>ce a number <strong>of</strong> organizations had not been<strong>in</strong>cluded. To supplement the SAHE directory, we obta<strong>in</strong>ed a copy <strong>of</strong> the Datal<strong>in</strong>e NGO directories(one each for the four prov<strong>in</strong>ces and the Capital) from the Trust for Volunteer Organizations (TVO). 3This directory had been compiled <strong>in</strong> 1991, and <strong>in</strong>cluded NGOs that had registered by the late 1980s.Those that stated that they were <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> education were sent questionnaires to gauge their currentstatus and <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> education. This process was time consum<strong>in</strong>g and the responsesdisappo<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g. However, we managed to complete this process for Balochistan, NWFP and S<strong>in</strong>dh.<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation sent back perta<strong>in</strong>ed mostly to the smaller NGOs and Community BasedOrganizations (CBOs). S<strong>in</strong>ce, we <strong>in</strong>itially planned to <strong>in</strong>clude only the larger NGOs <strong>in</strong> the sample,we began a fresh to compile a list <strong>of</strong> larger NGOs, on the basis <strong>of</strong> the SAHE directory and the NGOgrapev<strong>in</strong>e. Our selection criterion was that the NGO be runn<strong>in</strong>g formal primary schools (i.e. 5 years<strong>of</strong> school<strong>in</strong>g).Initially, for f<strong>in</strong>ancial and l<strong>in</strong>guistic reasons, the study was to be restricted to the Punjab. It wasthought that, as the largest prov<strong>in</strong>ce and with the largest number <strong>of</strong> NGO <strong>in</strong>terventions, the<strong>in</strong>stitutional f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from this prov<strong>in</strong>ce would be, by and large, relevant for the rest <strong>of</strong> the country.After much search<strong>in</strong>g, 50 NGO schools were selected from the Punjab. Because <strong>of</strong> the difficulty <strong>in</strong>f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g formal schools, even smaller NGOs were <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the sample. Once <strong>in</strong> the field, wediscovered that a substantial amount <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>formation reported was <strong>in</strong>accurate, even though it hadbeen given to us, <strong>in</strong> most cases, by the senior management <strong>of</strong> the organizations <strong>in</strong> question. <strong>The</strong>ma<strong>in</strong> problem was that many <strong>of</strong> the primary schools were not runn<strong>in</strong>g classes I-V as we required.Because we were not able to f<strong>in</strong>d 50 formal NGO schools <strong>in</strong> the Punjab, we had to expand the scope<strong>of</strong> the study to <strong>in</strong>clude the rest <strong>of</strong> the prov<strong>in</strong>ces. Much <strong>of</strong> the sampl<strong>in</strong>g work had to be carried out onthe basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation received on site, i.e. through various education-related pr<strong>of</strong>essionals andcommunities. Substitutions were made when those schools orig<strong>in</strong>ally <strong>in</strong> the sample could not besurveyed -- generally because the school did not run five classes, was closed due to W<strong>in</strong>ter break,was non-existent or too far away from a private school to justify a comparison between the two.<strong>The</strong> schools f<strong>in</strong>ally visited are listed <strong>in</strong> Appendix I, Table I-IV. As evident from this list, 7 out <strong>of</strong> the43 schools f<strong>in</strong>ally <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the sample were those <strong>of</strong> NGOs operat<strong>in</strong>g only one school. For themultiple school NGOs on the list, we randomly selected about 30 percent <strong>of</strong> the schools <strong>in</strong> thePunjab. When the fieldwork <strong>in</strong> the Punjab was complete, we cont<strong>in</strong>ued with random selection <strong>in</strong> theother Prov<strong>in</strong>ces to complete the target NGO selection. For the larger multi-school NGOs <strong>in</strong> the otherprov<strong>in</strong>ces, the selection ranged from 22 percent to 55 percent. Once the NGO school was selected,2 SAHE (1997).3 TVO (1994).2

SDPI Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper Series # 47we then visited the nearest government and private schools that ran classes up to class 5.objective <strong>in</strong> pursu<strong>in</strong>g this method was to m<strong>in</strong>imize location <strong>in</strong>fluences when compar<strong>in</strong>g schools. 4Our<strong>The</strong> fieldwork <strong>in</strong>volved a total <strong>of</strong> ten questionnaires, the details <strong>of</strong> which are attached as AppendixIII. <strong>The</strong>se <strong>in</strong>cluded solicit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation from students, teachers, households and communities. Wealso adm<strong>in</strong>istered tests to assess class III and class V student cognitive skills <strong>in</strong> mathematics andcomprehension and also cognitive skills <strong>of</strong> class V teachers. F<strong>in</strong>ally, meet<strong>in</strong>gs were held with theadm<strong>in</strong>istrations <strong>in</strong> the sample areas, and their op<strong>in</strong>ions on NGO <strong>in</strong>terventions were gauged.III.Conceptual framework<strong>The</strong> conceptual framework we used for view<strong>in</strong>g the vast and rich observations that emerged from thefield reports is the “pr<strong>in</strong>cipal-agent model”. 5 In the “pr<strong>in</strong>cipal-agent” context, the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal relies onthe agent to execute the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal’s agenda. A good outcome is likely when the agent has appropriate<strong>in</strong>centives to carry out the agenda <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal rather then carry<strong>in</strong>g out an <strong>in</strong>dependent agenda.Thus the “pr<strong>in</strong>cipal agent” problem can be viewed as one <strong>of</strong> ensur<strong>in</strong>g that there is agendacompatibility.<strong>The</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>cipal-agent problem occurs <strong>in</strong> the theory <strong>of</strong> the firm when the <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> the stockownersand the <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> the hired managers do not co<strong>in</strong>cide. <strong>The</strong> challenge is to structure <strong>in</strong>centives <strong>in</strong> away so that the two <strong>in</strong>terests are merged. Stock-options, as part <strong>of</strong> the pay or as a bonus formanagers, could be a solution. Aga<strong>in</strong>, even if the owners and managers have unified objectives, the<strong>in</strong>terests <strong>of</strong> the managers and those <strong>of</strong> the workers may deviate. One solution to the latter problem isto make the returns to workers tied to the pr<strong>of</strong>it <strong>of</strong> the firm. In this way, a harmony <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests maybe achieved across the board by l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g all remuneration to pr<strong>of</strong>its.<strong>The</strong> consumers can be viewed as the co-pr<strong>in</strong>cipal, s<strong>in</strong>ce the stock-holders, managers and workersshare <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>its are cont<strong>in</strong>gent on the consumers buy<strong>in</strong>g the good or service. This is particularly thecase if there is competition <strong>in</strong> the market and the consumer has the option <strong>of</strong> buy<strong>in</strong>g from anotherfirm if not satisfied with the product.In the same way, <strong>in</strong> government school<strong>in</strong>g, the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal is the public that via a circular process hasto ensure good public service. In a practical sense, the public mandate is entrusted to the m<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong>education as the l<strong>in</strong>e agency <strong>of</strong> the prov<strong>in</strong>cial governments. Authority for management andenforcement devolves down the hierarchy to the district and assistant education <strong>of</strong>ficers (DEO/AEO)and the field supervisors who are entrusted to do the monitor<strong>in</strong>g and enforcement. One could viewthe school adm<strong>in</strong>istration, heads and teachers as agents for provid<strong>in</strong>g good school<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> public’sonly mechanism for enforcement is compla<strong>in</strong>ts (voice), if there is no alternative to public school<strong>in</strong>g(exit), 6 or ultimately not vot<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>in</strong>efficient government.Our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs show that the voice option has seriously weakened as the rich parents have abandonedpublic schools <strong>in</strong> favor <strong>of</strong> private or NGO schools. <strong>The</strong> rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g students are generally from the4 About three-fourths (96 <strong>of</strong> the 129) <strong>of</strong> the schools were mixed, 18 were all girl and 15 were all boy schools.5 For a concise description refer to Stiglitz (1998).6 Hirschman, (1970).3

<strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong>: A Qualitative, Comparative Institutional Analysislower <strong>in</strong>come households and therefore the exit option is not a possibility for them either. 7 F<strong>in</strong>ally the electoraloption is a weak and crude enforcement mechanism for several reasons. First, concerned m<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong>ficialsmay rema<strong>in</strong> completely unaffected by a change <strong>in</strong> government, particularly at the lower adm<strong>in</strong>istrative level.Second, even if poor performance was signaled by the public, tenure and seniority based pay protects civilservice employees, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g teachers who do not perform well. Third, <strong>in</strong> practice, elections are an unlikelytool for such signal<strong>in</strong>g. Vot<strong>in</strong>g behavior is complex and determ<strong>in</strong>ed by many <strong>in</strong>fluences and, even if failure <strong>in</strong>social sector delivery plays a part <strong>in</strong> it, the message is likely to get lost.In a pr<strong>in</strong>cipal agent framework, success would mean that the prov<strong>in</strong>cial and local governments <strong>in</strong>ternalizewhat the public <strong>in</strong>terest is and deliver on it. Given the diffuse signals and weak enforcement mechanismreferred to above, public spiritedness needs to be <strong>in</strong>ternalized by senior civil service <strong>of</strong>ficials <strong>in</strong>dependentlysuch that they become the "pr<strong>in</strong>cipals." We discuss under what circumstances this might be possible <strong>in</strong> thegovernment school<strong>in</strong>g reform section.In private schools, the “pr<strong>in</strong>cipal” is the owner with reference to pr<strong>of</strong>it maximization. <strong>The</strong> “pr<strong>in</strong>cipal” is <strong>of</strong>tenalso the school adm<strong>in</strong>istrator or school head. As <strong>in</strong> the case <strong>of</strong> other goods and services purchased on themarket, the parents could be viewed as co-pr<strong>in</strong>cipals. As long as there is competition, there is an identity <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>terests s<strong>in</strong>ce good school<strong>in</strong>g is what parents want and that is also what will produce demand and high pr<strong>of</strong>its.<strong>The</strong> parents seek<strong>in</strong>g alternative school<strong>in</strong>g for their children is the enforcement mechanism for good school<strong>in</strong>g.In the absence <strong>of</strong> competition, compla<strong>in</strong>ts (voice) are all parents can resort to and there is no guarantee that thiswill meet with a response.Assum<strong>in</strong>g there is competition, and therefore an identity <strong>of</strong> parent and owner <strong>in</strong>terests, good school<strong>in</strong>gdepends, among other th<strong>in</strong>gs, on how effectively the “pr<strong>in</strong>cipal” motivates the “agents” (teachers). Soundselection, good tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and appropriate remuneration are among the tools that can be used for motivat<strong>in</strong>gteachers. However, fear <strong>of</strong> term<strong>in</strong>ation is an alternative tool for motivat<strong>in</strong>g teachers, and this is the one that wefound was used more frequently.<strong>The</strong> “pr<strong>in</strong>cipals” <strong>in</strong> one-<strong>of</strong>f NGO schools may operate much like private sector schools. <strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals maybe driven by a mission rather than a pr<strong>of</strong>it and this could be another source <strong>of</strong> motivation for the teachers asagents if they identify with the mission. In multi-school NGOs, the “pr<strong>in</strong>cipal” and the guardians <strong>of</strong> themission and quality is the NGO. It is the larger organization rather than the school that plays the role <strong>of</strong>monitor and enforcer <strong>of</strong> standards. Teachers work<strong>in</strong>g conditions, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and motivation are all tools to turnthem <strong>in</strong>to effective agents. Sometimes, the NGOs also mobilize communities to become contributors andenforces <strong>of</strong> standards via <strong>in</strong>formal channels or, more formally, via a parent-teacher association. In this case,the NGO effectively <strong>in</strong>vites the community, <strong>in</strong> which the school is situated, to be a co-pr<strong>in</strong>cipal.IV. Field reports evaluationA. Criteria <strong>in</strong> assess<strong>in</strong>g success<strong>The</strong> criterion for assess<strong>in</strong>g success <strong>in</strong>cluded the performance <strong>of</strong> class 3 and class 5 students and class 5teachers on comprehension and math tests, the state <strong>of</strong> discipl<strong>in</strong>e and confidence <strong>of</strong> students, motivation,7 We constructed a wealth <strong>in</strong>dex based on durable goods and mode <strong>of</strong> transport possessed. By this criterion, 59percent <strong>of</strong> the children <strong>of</strong> government schools came from the most deprived households while this was true for38 percent <strong>of</strong> private and NGO schools. Aga<strong>in</strong>, while only 5 percent <strong>of</strong> the children from government schoolscame from the wealthiest households, this was true for 23 percent and 22 percent <strong>of</strong> private and NGO schoolchildren. Thus the household wealth pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> the NGO and private school children was virtually identical andmuch higher than that <strong>of</strong> government school children.4

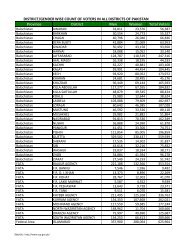

SDPI Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper Series # 47dedication, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and experience <strong>of</strong> teachers, whether students and/or teachers cheated <strong>in</strong> the tests, physicalfacilities <strong>of</strong> the school, availability <strong>of</strong> school supplies and the quality <strong>of</strong> school adm<strong>in</strong>istration andmanagement.B. Comparative overview <strong>of</strong> success<strong>The</strong> table below <strong>in</strong>dicates the evaluation <strong>of</strong> the field team concern<strong>in</strong>g the 43 sets <strong>of</strong> government, privateand NGO schools across the country. 8 As <strong>in</strong>dicated <strong>in</strong> the sampl<strong>in</strong>g section, the NGO schools wereselected first and the closest government and private schools subsequently selected for <strong>in</strong>vestigation. <strong>The</strong>table below <strong>in</strong>dicates how many <strong>of</strong> the schools <strong>in</strong> the sample were viewed as successful or not successfulby the field-teams based on the criteria described above.Table 1: A comparative tally <strong>of</strong> the success and failure <strong>of</strong> government, private, and NGO schoolsType <strong>of</strong> school/ Evaluation Successful Not successful In-betweenGovernment 5 32 6Private 19 17 7NGO 31 8 4Source: Survey field-team evaluation<strong>The</strong> table clearly <strong>in</strong>dicates that the NGO schools are the most likely to be successful followed by privateschools. That only 5 out <strong>of</strong> 43 government schools were viewed as successful confirms what is now wellknown i.e. that the state <strong>of</strong> government basic education is abysmal and urgently <strong>in</strong> need <strong>of</strong> reform.As mentioned earlier, one <strong>of</strong> the criteria <strong>of</strong> success was the performance <strong>of</strong> class 3 and class 5 studentsand class 5 teachers on comprehension and math tests. While we give more weight to the overallevaluation <strong>of</strong> the field-teams, it is nonetheless <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to observe the results on the tests adm<strong>in</strong>isteredby the field-teams that are reported below <strong>in</strong> Table 2.Table 2: Percentage marks on comprehension and math tests for teachers and class 3 and classType <strong>of</strong>Schools5 students by school type.Teacher Scores Students Scores,Class 3Student Scores,Class 5Math Comp. Math Comp. Math Comp.NGO 5.9(2.7)24.5(3.3)2.6(1.2)10.1(4.9)4.9(1.3)16.7(3.6)Private 6.1(3.0)23.1(5.3)2.4(1.2)7.1(3.7)4.5(1.7)13.6(4.4)Govt. 5.3(3.0)23.2(4.7)1.5(1.3)4.2(3.4)3.8(1.8)10.1(4.7)Notes: Comprehension and math tests for students were developed us<strong>in</strong>g the syllabi <strong>of</strong> class 3 andclass 5 <strong>of</strong> various textbook boards. Comprehension test for teachers was taken from an IFPRIproject on education <strong>in</strong> rural <strong>Pakistan</strong> [Alderman et. al., (1995)], whereas a math test from thesame project was adapted based on pre-tests.Figures <strong>in</strong> parenthesis are standard deviations on mean scores for teachers and mean <strong>of</strong>class mean scores for students across all 43 schools. <strong>The</strong> maximum scores on teacher testswere 10 and 30 and on student tests 20 and 25 for math and comprehension respectively.8 <strong>The</strong> fieldwork began on September 9, 1998 and cont<strong>in</strong>ued until December 28, 1998.5

<strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong>: A Qualitative, Comparative Institutional AnalysisSeveral po<strong>in</strong>ts are evident from Table 2. First, children <strong>in</strong> NGO schools had the best mean performance<strong>in</strong> both subjects and both classes. Second, while teacher comprehension scores were highest for NGOteachers, teacher math scores were highest for private school teachers. <strong>The</strong> performance <strong>of</strong> governmentteachers was the poorest <strong>in</strong> both subjects but not by much <strong>in</strong> the case <strong>of</strong> comprehension tests. However,this still rema<strong>in</strong>s a poor show<strong>in</strong>g s<strong>in</strong>ce government teachers have similar education qualifications to NGOand private school teachers and much higher pre-service tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. NGOs <strong>in</strong>vest the most <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>-servicetra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. 9 Third, on average, government school students had a much lower scale <strong>of</strong> academicachievement <strong>in</strong> class three and this rema<strong>in</strong>ed true on an absolute level by class five. However, the relativega<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> scores between class three and class five was much higher <strong>in</strong> government schools which issuggestive <strong>of</strong> the potential for improvement. Fourth, the variation <strong>in</strong> scores among students forgovernment schools was generally the highest or close to the highest and it was the lowest or close to thelowest for NGO schools. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> cheat<strong>in</strong>g among students and teachers was highest <strong>in</strong>government schools and lowest <strong>in</strong> NGO schools and so government school teacher and student scores are<strong>in</strong>flated.In the sections that follow, we <strong>in</strong>dicate what accounted for success and failure <strong>of</strong> the three different k<strong>in</strong>ds<strong>of</strong> schools and what reform lessons are evident.1. Government schoolsGovernment basic education is by far the most important school<strong>in</strong>g for us to focus on. This is partlybecause <strong>of</strong> its much larger scale but, more so, because, with the onset <strong>of</strong> private and NGO school<strong>in</strong>g, theclients <strong>of</strong> government school<strong>in</strong>g are now the most poor and deprived students. Any successful program<strong>of</strong> human development must address the needs and entitlements <strong>of</strong> this class. This sub-section conta<strong>in</strong>s ageneral discussion <strong>of</strong> government school<strong>in</strong>g followed by a discussion <strong>of</strong> issues based on specificobservations.a. General discussion<strong>The</strong> high failure rate <strong>of</strong> government schools is a serious cause <strong>of</strong> concern if we view “even<strong>in</strong>g the odds”<strong>in</strong> a class based society as a fundamental state responsibility. <strong>The</strong> clients <strong>of</strong> government schools aregenerally poor and illiterate. 10 <strong>The</strong> richer parents are abandon<strong>in</strong>g government schools <strong>in</strong> droves.Between 1991 and 1996-97, the growth <strong>of</strong> enrollment <strong>in</strong> non-government schools was 61 percent for boysand 131 percent for girls. 11 <strong>The</strong> better <strong>of</strong>f parents quite clearly <strong>in</strong>dicated to us that government schoolswere <strong>in</strong>capable <strong>of</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g a decent education. <strong>The</strong> poor parents were <strong>of</strong>ten aware <strong>of</strong> the poor standard<strong>of</strong> education be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>fered to their wards, but were unable to do much about this because <strong>of</strong> economiccircumstances. Even then, we noticed that many relatively poor parents stretched themselves to provide anon-government education to their children either out <strong>of</strong> genu<strong>in</strong>e concern for their children’s education,and sometimes because non-government education has also become a mark <strong>of</strong> status <strong>in</strong> rural society. 12Often, it was the bright children that parents removed from government schools.9 <strong>The</strong> mean years <strong>of</strong> education for government, private and NGO teachers were 12.9, 12.3 and 12.9 years, meanpre-service tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 1.05, 0.4 and 0.5 years and mean <strong>in</strong>-service tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g was 0.54, 0.2 and 1.3 monthsrespectively.10 Eleven percent <strong>of</strong> the fathers and 27 percent <strong>of</strong> the mothers <strong>of</strong> government school students were illiteratecompared to 5 percent and 5 percent for NGO schools and 16 percent and 18 percent respectively for privateschools respectively. <strong>The</strong>se numbers are way below the national average because they represent theresponses <strong>of</strong> parents <strong>of</strong> school children. For the wealth <strong>in</strong>dex see fn. 7.11 Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong> (1998, p. 23).12 Non-government refers to both private and NGO school<strong>in</strong>g. In this regard, NGO could probably be improvedupon as an acronym to suggest what they are rather than what they are not. Public Interest Organization (PIO)is ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g some currency <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong>.6

SDPI Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper Series # 47This exodus <strong>of</strong> the richer children and the brighter poor children to non-government schools isaccentuat<strong>in</strong>g the crisis <strong>of</strong> government education. <strong>The</strong> wealthier parents are the most likely to compla<strong>in</strong>and play a pr<strong>in</strong>cipal’s role to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> standards. <strong>The</strong> brighter children are the most likely to raise thegeneral level <strong>of</strong> the class. With these sources <strong>of</strong> countervail<strong>in</strong>g pressure gone, rural public sectoreducation will deteriorate further. Thus the children <strong>of</strong> poor parents <strong>of</strong>ten don’t make it to school and,those that do, have little hope <strong>of</strong> gett<strong>in</strong>g very far <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly competitive world. 13Concerned and <strong>in</strong>terested parents <strong>of</strong> children <strong>in</strong> government schools were generally the exception ratherthan the rule. Thus teachers got away with educational murder. Not only did they wantonly neglect theirduties, they also used the students to do their chores and br<strong>in</strong>g gratuities. <strong>The</strong>y also charged specialillegal fees and run their own bus<strong>in</strong>esses on the side. Focus group meet<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong>ten showed illiterate andpoor parents satisfied because they did not know any better. Often they seemed content that their childrenwere <strong>in</strong> school and at other times they seemed to view the school as a convenient child sitt<strong>in</strong>garrangement. However, even this service was not reliable, s<strong>in</strong>ce many parents and communitiescompla<strong>in</strong>ed that students came and went as they pleased and this was confirmed by field observation.While government teachers were more highly paid than non-government teachers, some parents wereunder the impression that government teachers were very poorly paid and hence had no option but to run<strong>in</strong>dependent bus<strong>in</strong>esses on the side to supplement their meager <strong>in</strong>come. 14 Here it important toacknowledge that be<strong>in</strong>g paid more than private sector teachers does not constitute good pay. 15One issue that parents and the community dwelt on was whether or not the teachers were from the village.Teachers who did not reside <strong>in</strong> the village were <strong>of</strong>ten late and absent. However, they were less likely tobe harsh to children <strong>of</strong> a particular beradari (clan) and more receptive to compla<strong>in</strong>ts from the parentsabout the school<strong>in</strong>g. Thus overall, they were viewed as more effective.Currently, the surprise visitor to a government school is likely to confront very poor facilities, very highstudent and teacher absenteeism, gossip<strong>in</strong>g and dis<strong>in</strong>terested teachers and an unrestra<strong>in</strong>ed student bodyrunn<strong>in</strong>g wild. In one case, all the teachers were absent and class five students were manag<strong>in</strong>g the school.Teachers blame the parents for a lack <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest and the parents blame the teachers for a lack <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest.<strong>The</strong>re are elements <strong>of</strong> truth to both allegations. However, reform needs to start <strong>in</strong> the school and filter outto the home. An angry and accus<strong>in</strong>g household or a dis<strong>in</strong>terested household is not likely to be a veryreceptive one.<strong>The</strong> power <strong>of</strong> teachers, among other factors, underm<strong>in</strong>es public sector school<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong>re are at least fivesources <strong>of</strong> teacher power. First, the teachers as government servants have tenure and thus face little threat<strong>of</strong> los<strong>in</strong>g their job if they perform poorly. Second, there is very little oversight by education <strong>of</strong>ficers soteachers feel secure <strong>in</strong> their neglect. Third, even if they are caught out, they f<strong>in</strong>d political authorities tobat for them. Fourth, even if they don’t have political connections, they have a teacher’s association13 Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong> (1998, p. 33).14 <strong>The</strong> mean monthly salary <strong>of</strong> government teachers was Rs. 3,567 (Rs. 1537 standard deviation). <strong>The</strong> meanmonthly salary <strong>of</strong> private and NGO teachers was Rs. 1,800 (Rs. 2,379, sd) and Rs. 2,317 (Rs. 2,339)respectively.15 <strong>The</strong> mean salary <strong>of</strong> government school teachers <strong>of</strong> Rs. 3,567 is about equal to the mean monthly salary <strong>of</strong>unskilled workers (us<strong>in</strong>g a straight average <strong>of</strong> the daily wage for the national and four prov<strong>in</strong>cial capitals andmultiply<strong>in</strong>g by 30) and less than half the monthly salary <strong>of</strong> skilled workers like masons and carpenters[Government <strong>of</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong>, Economic Survey 1998-99, Statistical Supplement, (1999, p. 143)]. However,government teachers are entitled to benefits like a provident fund, health facilities and pension that are notaccessible to daily wage-workers.7

<strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong>: A Qualitative, Comparative Institutional Analysisbatt<strong>in</strong>g for them. Fifth, they face a very poor and uneducated constituency <strong>of</strong> parents, which provides nothreat or countervail<strong>in</strong>g power. Thus, under the current circumstances, public sector teachers are unlikelyto be good “agents.”b. Some notable specific practices or f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsi. Teachers and teacher practices: In one school, the field-team left and returned an hourlater for some follow-up questions. While the school should still have been <strong>in</strong> session, <strong>in</strong> fact it had beenlocked, and the teachers were play<strong>in</strong>g cricket. Parents <strong>in</strong> other schools also compla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>of</strong> teachers be<strong>in</strong>gmore <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> cricket than <strong>in</strong> the children. Some <strong>in</strong>stances <strong>of</strong> the lack <strong>of</strong> teacher awareness <strong>in</strong>cludethe <strong>in</strong>ability <strong>of</strong> a teacher to recall either the number or names <strong>of</strong> students <strong>in</strong> his classes. While thisforgetfulness could be forgiven, draw<strong>in</strong>g a complete blank on a maths test is less forgivable. Similarly, itwas shock<strong>in</strong>g to discover that the headmistress <strong>of</strong> a school <strong>in</strong> the Punjab was unaware <strong>of</strong> the capital city<strong>of</strong> the Prov<strong>in</strong>ce. It is not surpris<strong>in</strong>g then that class three students <strong>in</strong> one school were even unable to writetheir names. However, the fact that political appo<strong>in</strong>tments took place was obvious from the hir<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> aretarded person as a teacher <strong>in</strong> one <strong>of</strong> the school’s visited.Parents resented the wide practice <strong>of</strong> compell<strong>in</strong>g students to take tuition at the same time as they wastedteach<strong>in</strong>g time dur<strong>in</strong>g school hours. Of course, only the relatively more prosperous parents could affordthe tuition, so even with<strong>in</strong> government schools, their was a social divide. Beat<strong>in</strong>gs were also observed tobe a common practice, even <strong>in</strong> girls’ schools, as was compell<strong>in</strong>g students to do chores. In one school,even the district education <strong>of</strong>ficer (DEO) borrowed children for his errands.Parents also compla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>of</strong> the teacher’s be<strong>in</strong>g extractive. Students were pressured to br<strong>in</strong>g gifts <strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>dand pay special fees. At other times, teachers demanded money for rent even if the government allocationcovered rent. In one case, the parents po<strong>in</strong>ted out that the teachers demanded Rs. 50 per annum as fees(without a receipt) while they knew the fees were only Rs. 27.ii. School conditions and facilities: School facilities <strong>in</strong> general were abysmal. We notesome observations here to re<strong>in</strong>force the po<strong>in</strong>t. Children <strong>of</strong>ten sat on a mat and <strong>in</strong> one school they werefound sitt<strong>in</strong>g on the wet floor while <strong>in</strong> many they were required to br<strong>in</strong>g their own sack to sit on. Inseveral cases, teachers’ aids, kits and charts were available but locked away <strong>in</strong> the head’s <strong>of</strong>fice.Stationary was chronically <strong>in</strong> short supply. <strong>The</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> electricity due to the non-payment <strong>of</strong> a bill wasobserved to be a problem <strong>in</strong> more than one school. Schools were crowded with student-teacher ratios <strong>of</strong>50-60 per class and multi-grade teach<strong>in</strong>g was quite common due to short staff<strong>in</strong>g. Toilets were generallyfilthy and water <strong>of</strong>ten not <strong>in</strong> supply.iii. Absenteeism and teacher dis<strong>in</strong>terest: Absenteeism and the lack <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest wereserious problem among both teachers and students. Up to two-thirds to fifty percent <strong>of</strong> the students werefound to be absent on the day <strong>of</strong> the field-visit. 16 In some schools, even though students were absent(forty percent <strong>in</strong> one case), teachers marked them present anyway. In other schools, teachers did notbother to mark the attendance register. In one school, fifty percent <strong>of</strong> the students did not bother to returnafter the recess. Even if the teachers were present, they were <strong>of</strong>ten found chatt<strong>in</strong>g while the students ranwild. In one school, only one out <strong>of</strong> the six teachers present was actually found teach<strong>in</strong>g. In anotherschool, a peon was found teach<strong>in</strong>g classes and <strong>in</strong> another school, students were used to perform the duties16 Student absenteeism was the only statistic where the data did not confirm the impression formed by fieldobservation. <strong>The</strong> absentee rate, calculated as the total days absent as a percent <strong>of</strong> the total school days <strong>in</strong> theApril to June 1999 period, was 9.9, 15.6 and 10.7 percent for NGO, private and government schoolsrespectively. <strong>The</strong> higher absentee rate for private schools was a surprise.8

SDPI Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper Series # 47<strong>of</strong> peons and chowkidars (guards). Many community <strong>in</strong>terviews <strong>in</strong>dicated that teachers never botheredgiv<strong>in</strong>g homework.iv. Quality: Perhaps there was no greater <strong>in</strong>dictment <strong>of</strong> government school<strong>in</strong>g than the factthat the government teachers were enroll<strong>in</strong>g their own children <strong>in</strong> private schools. Another perspective onthis was <strong>of</strong>ten provided by parents who had actually attended a particular school themselves and hencefelt very committed to it. Invariably, their recollections were a confirmation <strong>of</strong> decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g standards and<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g teacher dis<strong>in</strong>terest over time.v. Management: <strong>The</strong>re is little one could expect by way <strong>of</strong> good management given the dis<strong>in</strong>terest<strong>of</strong> the head and other teachers. <strong>The</strong> head teacher <strong>in</strong> one case was runn<strong>in</strong>g her own private school on theside and <strong>in</strong> another case ran a build<strong>in</strong>g material bus<strong>in</strong>ess. <strong>The</strong> head teachers rout<strong>in</strong>ely came late.Some <strong>of</strong> the worst travesties <strong>in</strong>cluded a school that was used as a gambl<strong>in</strong>g den where addicts hung outand another school <strong>in</strong> which the last DEO visit took place three years ago. In this regard, schools closerto district headquarters had better oversight. However, by the same token, the second shift <strong>in</strong> a doubleshift school went from bad to worse s<strong>in</strong>ce they had less fear <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g observed after regular hours.2. Private schoolsAs <strong>in</strong>dicated <strong>in</strong> Table 1, private schools presented the greatest contrast <strong>in</strong> performance. <strong>The</strong> worst oneswere <strong>of</strong>ten run as a family bus<strong>in</strong>ess with rented build<strong>in</strong>gs that were completely <strong>in</strong>adequate for school<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>The</strong>se build<strong>in</strong>gs were crowded, poorly ventilated, poorly lit, hot, short <strong>of</strong> even poor quality furniture, haddirty bathrooms, no clean dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water and no play area. 17 In one school, the children were foundplay<strong>in</strong>g on the ro<strong>of</strong>. Several <strong>of</strong> the schools practiced multi-grade teach<strong>in</strong>g or otherwise had a distract<strong>in</strong>gteach<strong>in</strong>g environment. In one case, the teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the veranda was too close to the teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> thecourtyard and <strong>in</strong> another the converted warehouse produced too much echo. By contrast, some schoolseven had well stocked libraries that they encouraged students to use and computers that they utilized toprovide <strong>in</strong>struction to the higher grades. One school even had a tuck-shop that operated on a self-serviceself-pay<strong>in</strong>g basis.<strong>The</strong> teachers were <strong>of</strong>ten paid poorly, not tra<strong>in</strong>ed and made to work hard. 18 Several teachers compla<strong>in</strong>edabout their poor pay. <strong>The</strong> turnover rate was stated to be high. <strong>The</strong> higher paid, much more laid back andtenured government teach<strong>in</strong>g positions were obviously very attractive. A year or two <strong>of</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>private schools was viewed as enough to establish credentials for a more secure government job.Yet despite this, teachers were very <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>in</strong>dustrious, discipl<strong>in</strong>ed and motivated. <strong>The</strong> threat <strong>of</strong> job loss nodoubt had someth<strong>in</strong>g to do with this. Students were also generally discipl<strong>in</strong>ed, confident and well turnedout, even if the performance on the tests was not good. Homework was <strong>in</strong> general regularly assigned andcorrected, someth<strong>in</strong>g the parents noted and greatly appreciated. Teachers <strong>in</strong> one school stayed severalhours after school to both grade homework and prepare the next day class plans.Parent teacher contact was much higher and the school adm<strong>in</strong>istration much more responsive to parentalconcerns. However, except for an <strong>in</strong>novative “mother’s day” featur<strong>in</strong>g student performances that was17 We generated a physical quality <strong>in</strong>dex based on the availability <strong>of</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g: boundary wall, desks, chairs, taats(mats), <strong>in</strong>door teach<strong>in</strong>g, electricity, fans, dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water, washrooms (both availability and quality) and library.Based on this, the quality score ranged from 0 to a maximum <strong>of</strong> 12. <strong>The</strong> mean score on this <strong>in</strong>dex forgovernment, private and NGO schools was 5.2 (sd., 2.71), 9.0 (sd., 1.49) and 10.1(sd., 1.16) respectively.18 See fns. 9 and 14.9

<strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong>: A Qualitative, Comparative Institutional Analysisdevised by one school to get the mother’s more <strong>in</strong>volved, parent teacher contact was generally not<strong>in</strong>stitutionalized. 19 But teachers <strong>in</strong> general made more effort to apprise parents <strong>of</strong> the child’sperformance. High absenteeism was the exception rather than the rule.While fees were <strong>in</strong> general much higher than <strong>in</strong> government schools and too high for the poor, severalschools ran scholarship programs for the able poor students and had concession based fee structures. 20One school even had the rich parents contribute to the fees <strong>of</strong> the poor ones.<strong>The</strong> curse <strong>of</strong> private tuition was still present with many <strong>of</strong> the richer parents buy<strong>in</strong>g this for their children,perhaps as a substitute to giv<strong>in</strong>g their own time, and many teachers supplemented their <strong>in</strong>come with it.Private schools were <strong>of</strong>ten able to get away with poor performance because relatively uneducated parentshad only abysmal government school<strong>in</strong>g to compare private school<strong>in</strong>g with. Indeed, much <strong>of</strong> thediscussion <strong>of</strong> focus group meet<strong>in</strong>gs with parents whose children were <strong>in</strong> NGO and private schoolscentered on the disastrous state <strong>of</strong> government school<strong>in</strong>g. Many put their children <strong>in</strong> the private school asmuch from a vague sense <strong>of</strong> do<strong>in</strong>g best by their child as for the status symbol this has come to represent.Parents took great pride <strong>in</strong> Oxford University Press books on the syllabus – referred to as an “OxfordSyllabus.” More disturb<strong>in</strong>g, poor parents sometimes judged quality by the fee they were pay<strong>in</strong>g. In acouple <strong>of</strong> community focus group meet<strong>in</strong>gs, parents suggested that government school<strong>in</strong>g should beabolished and subsidies provided to non-government schools to make them more affordable. 21<strong>The</strong> more educated parents were <strong>of</strong>ten more vocal, expected more and compla<strong>in</strong>ed hard s<strong>in</strong>ce they werepay<strong>in</strong>g what they perceived to be a high price. Thus they exercised their right as co-pr<strong>in</strong>cipals to demandstandards. In some cases, even illiterate parents who were pay<strong>in</strong>g what they viewed as very high fees hadhigh expectations and were vocal about what they perceived as an <strong>in</strong>adequate service. 22 SMCs werelargely irrelevant for private schools. Parents felt they were pay<strong>in</strong>g a good price and that is where theirresponsibility ended. In turn, they expected the school to deliver the education. This was true across theboard <strong>in</strong> a majority <strong>of</strong> schools surveyed, but not surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, was more the case with private sectorschools. Several educated and discern<strong>in</strong>g parents who had removed they children from governmentschools claimed that there was a noticeable improvement <strong>in</strong> the level their children had atta<strong>in</strong>ed and theprogress the children were mak<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>The</strong> field team found cheat<strong>in</strong>g by students and even teachers (tak<strong>in</strong>g help from colleagues) much moreprevalent <strong>in</strong> government and private schools. Private school teachers operat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a “for pr<strong>of</strong>it”environment probably felt under pressure to be able to show good results. <strong>The</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess motivationproduced some positive results such as educational awareness campaigns. One school run by a group <strong>of</strong>friends started music classes, computer classes and street assemblies to attract parent attention and raiseenrollments. This motivation could also <strong>in</strong>duce negative behavior and one dissatisfied community allegedthat the zero failure rate achieved by the school <strong>in</strong> grade exams resulted from the bribes given by the19 Only 4 out <strong>of</strong> the 43 private schools had a PTA (parent teacher association) or SMC (school managementcommittee) while this was the case for 29 government schools (mandatory) and 23 NGO schools (optional).20 <strong>The</strong> mean fees monthly fee was Rs. 3 (sd., Rs. 4) for government schools, Rs. 108 (sd., Rs. 49) for privateschools and Rs. 121 (sd., Rs. 73) for NGO schools.21 While it may be difficult to justify subsidiz<strong>in</strong>g a commercial activity, the government could ensure that taxauthorities do not harass private schools as seems to be happen<strong>in</strong>g accord<strong>in</strong>g to press reports.22 It was difficult to f<strong>in</strong>d a completely consistent pattern for parental <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> school<strong>in</strong>g across the threetypes <strong>of</strong> schools. Sometimes, very educated parents were complaisant about very poor private sector school<strong>in</strong>gas though they had done the best by their children and need not worry further. While the poor and illiterate weregenerally unaware and dis<strong>in</strong>terested, they sometimes compla<strong>in</strong>ed vociferously about the poor service delivery <strong>of</strong>government schools.10

SDPI Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper Series # 47school adm<strong>in</strong>istration. In another school where test results were poor, the field-team observed thatteachers were giv<strong>in</strong>g very high marks to the students <strong>in</strong> a cynical attempt to impress uneducated parents.<strong>The</strong> bottom l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> good performance was good management and, more <strong>of</strong>ten than not, this h<strong>in</strong>ged on anexceptional and dedicated pr<strong>in</strong>cipal or adm<strong>in</strong>istrator who exercised oversight and led by example. Such<strong>in</strong>dividuals were <strong>of</strong>ten concerned with <strong>in</strong>fus<strong>in</strong>g a high moral character <strong>in</strong> the children, someth<strong>in</strong>g thecommunity focus group was highly appreciative <strong>of</strong>. Staff that taught <strong>in</strong> schools that they had themselvesattended, whether <strong>in</strong> the private or government sectors, <strong>of</strong>ten developed an emotional attachment andworked hard. One school re<strong>in</strong>forced such efforts by giv<strong>in</strong>g bonuses to devoted teachers.3. NGO schools 23NGO school<strong>in</strong>g was easily the most successful. However, not all NGO schools visited were a success.We classified NGO schools <strong>in</strong> our sample based on whether they were one-<strong>of</strong>f NGO schools or part <strong>of</strong> amulti-school program with a support system. <strong>The</strong> latter <strong>of</strong>ten resulted <strong>in</strong> better management. With<strong>in</strong>these categories, we found schools that had a secular or a religious or ideological orientation. <strong>The</strong>ideological orientation was important <strong>in</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g NGO motivation and this dist<strong>in</strong>guished theprom<strong>in</strong>ent multi-school NGO programs from the for pr<strong>of</strong>it private school <strong>in</strong> most cases.NGO schools were viewed as private schools <strong>in</strong> the public perception and educat<strong>in</strong>g a child <strong>in</strong> an NGOschool also represented a “status symbol.” 24 However, while those NGOs that charged a fee had higherfees (fn. 20), 77 percent <strong>of</strong> the NGOs reported charg<strong>in</strong>g no fee. Thus there was a real dist<strong>in</strong>ction betweenschools run for pr<strong>of</strong>it and those operat<strong>in</strong>g on a non-pr<strong>of</strong>it basis.a. <strong>The</strong> one-<strong>of</strong>f unsuccessful NGO schools<strong>The</strong>se schools had practices similar to the unsuccessful private schools. <strong>The</strong> schools were <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>in</strong> rentedbuild<strong>in</strong>gs that were crowded and totally <strong>in</strong>appropriate for school<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> notorious practice <strong>of</strong> giv<strong>in</strong>gchildren tuition was witnessed <strong>in</strong> such NGO schools as <strong>in</strong> private schools.For one school, the positive response elicited from the community <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancially sound farmers aga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>dicated how easy it sometimes is to fool parents. <strong>The</strong> latter were impressed with the small classes,discipl<strong>in</strong>e and extra-curricula activities. However, the focus group meet<strong>in</strong>g revealed that the teacherssolicited the assistance <strong>of</strong> shop-keepers near the school to keep an eye on students bunk<strong>in</strong>g classes.b. <strong>The</strong> one-<strong>of</strong>f successful NGO schools<strong>The</strong>re were several examples <strong>of</strong> successful one-<strong>of</strong>f NGO schools where practices differed from thosementioned <strong>in</strong> sub-section a) above. <strong>The</strong> Anjuman-e-Asatasa only hired teachers that had earned an<strong>in</strong>termediate degree (A level or high school equivalent) as a m<strong>in</strong>imum qualification and had been tra<strong>in</strong>edas teachers. Discipl<strong>in</strong>e was good and the students were well behaved and enthusiastic. <strong>The</strong> studentteacherrapport was notable and this was probably facilitated by the jo<strong>in</strong>t projects that they engaged <strong>in</strong>.<strong>The</strong> So<strong>of</strong>i Foundation school stood out because <strong>of</strong> it’s highly equipped large build<strong>in</strong>g, impressive libraryand very qualified teachers. In both schools, the poor parents felt burdened by the fees and the very poorregretted be<strong>in</strong>g excluded.23 For an account <strong>of</strong> NGO school<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> general refer to Baqir (1998) and for a specific example <strong>of</strong> communitybased school<strong>in</strong>g to Khan (1998).24 <strong>The</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ction between an NGO and private school is <strong>of</strong>ten nom<strong>in</strong>al. <strong>The</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istrations <strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong>private schools we visited stated that the schools had been created by an NGO merely for registration with theeducation authorities. <strong>The</strong>se NGOs had no say or <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> the function<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the school and, <strong>in</strong> fact, <strong>in</strong>many cases, they ceased to exist as soon as the registration had been completed.11

<strong>The</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Basic</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pakistan</strong>: A Qualitative, Comparative Institutional Analysis<strong>The</strong> Mithi <strong>Education</strong>al Society ran a successful school <strong>in</strong> Mithi, Tharparker cater<strong>in</strong>g ma<strong>in</strong>ly to a H<strong>in</strong>ducommunity. <strong>The</strong> NGO had to work very hard to conv<strong>in</strong>ce the community to allow females to teach <strong>in</strong> theschool. However, they were successful and managed to get together a team <strong>of</strong> qualified, well-tra<strong>in</strong>ed andcommitted teachers. <strong>The</strong> proud parents felt that, as a result, their <strong>of</strong>fspr<strong>in</strong>g were gett<strong>in</strong>g an education thatwould make them capable <strong>of</strong> even compet<strong>in</strong>g with students from Karachi.<strong>The</strong> English Grammar School Swabi was impressive. <strong>The</strong> school build<strong>in</strong>g and classes were good andstudents were <strong>in</strong> clean uniforms and well discipl<strong>in</strong>ed. All students on the register were present on the day<strong>of</strong> the field visit. Another surprise for the field team was that the toilets even had soap and towels. Most<strong>of</strong> the teachers had earned a Masters’ degree and were dedicated and competent. <strong>The</strong> team sprit observedamong teachers was commendable and the student-teacher relations were friendly. <strong>The</strong> school providedfree education to thirty students and had plans to start computer classes. <strong>The</strong> parents participated <strong>in</strong>school activities and the school adm<strong>in</strong>istration was responsive to parents’ suggestions. <strong>The</strong> parents werevery satisfied and mentioned that their children seemed dull before they started attend<strong>in</strong>g this school.Due to the higher standard, the school <strong>of</strong>ten made children transferr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> from government schools stayback <strong>in</strong> the same class.<strong>The</strong> Sunsh<strong>in</strong>e Public School was partially funded by the Swabi Women’s Welfare Organization andhence, compared to the private sector schools, charged more modest fees. While the rented apartmentbuild<strong>in</strong>g was not completely adequate and the teachers were not tra<strong>in</strong>ed, both students and teachers didvery well <strong>in</strong> the tests. <strong>The</strong> teachers also tried to <strong>in</strong>culcate good habits like manners, punctuality andcleanl<strong>in</strong>ess. A surprise for one field-team member was witness<strong>in</strong>g a student carry a piece <strong>of</strong> torn paper tothe dustb<strong>in</strong>. <strong>The</strong> parents attributed success to the oversight <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal.c. <strong>The</strong> badly managed multi-school NGO programsOne Anjuman (association) had adopted 13 primary schools at the time <strong>of</strong> the field visit, but most werenew and only one <strong>of</strong> these had students <strong>in</strong> class five. <strong>The</strong> student-teacher rapport seemed good, but thecommunity was quite negative about the casual attitude <strong>of</strong> the school adm<strong>in</strong>istration. No one seemedaware <strong>of</strong> the role <strong>of</strong> the Anjuman <strong>in</strong> manag<strong>in</strong>g the school. One community member thought that theschool was just a tax break for the owner <strong>of</strong> the nearby Fruit Farm. Parents thought the fee was too highfor the product delivered, and some mentioned they would transfer their child, even if to a governmentschool.Five out <strong>of</strong> the six Hira schools, founded by the Anjuman-e-Asataza (Association <strong>of</strong> Teachers), <strong>in</strong> oursample were successful. <strong>The</strong> sixth was like the typical unsuccessful private sector school. <strong>The</strong> classroomswere narrow and dark and multi-grade teach<strong>in</strong>g was be<strong>in</strong>g practiced. Students lacked discipl<strong>in</strong>eand the teachers seemed dis<strong>in</strong>terested. Parents were not literate and seemed unable to discern whatrepresented educational quality. <strong>The</strong> religious affiliation <strong>of</strong> the school was however a source <strong>of</strong> comfortfor parents, and they therefore will<strong>in</strong>gly sent their daughters to the school.Two <strong>of</strong> the four schools run by an old and well-established NGO <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>dh prov<strong>in</strong>ce were no differentfrom the shoddy private sector schools. In one <strong>of</strong> the two schools, the teacher tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g was poor and thestudents were found giv<strong>in</strong>g tuition. While there was a general body (twenty-six NGO and communitymembers) to run the school, it made little difference to the school’s function<strong>in</strong>g. In the other school,management by the NGO was very lax. No attendance register was ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed and teachers rout<strong>in</strong>elycame late. Four <strong>of</strong> the classes were be<strong>in</strong>g held <strong>in</strong> a veranda, which made concentration difficult forteachers and students. Class 3 students were unable to read the math. and comprehension tests <strong>in</strong> S<strong>in</strong>dhi,even though that was the medium <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>struction. While ten percent <strong>of</strong> the students were supposed to be12

SDPI Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper Series # 47allowed to attend free, students had dropped out because they could not afford the fee. <strong>The</strong> communityhad been mobilized and was fully <strong>in</strong>volved, <strong>in</strong>terested and active and represented on the PTA. <strong>The</strong>y hadcontributed the land and towards the cost <strong>of</strong> the build<strong>in</strong>g and, despite the poor performance <strong>of</strong> the school,were will<strong>in</strong>g to cont<strong>in</strong>ue contribut<strong>in</strong>g.d. <strong>The</strong> well managed multi-school religious NGO programs<strong>The</strong>re were two Asgharia <strong>Education</strong>al & Welfare Society (AEWS) Schools <strong>in</strong> the sample and it was clearthat the NGO management was sound. <strong>The</strong> teachers were very pr<strong>of</strong>essional and committed even thoughnot highly qualified. <strong>The</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>cipal was also very dedicated and pr<strong>of</strong>essional and tra<strong>in</strong>ed teachers on hisown accord. <strong>The</strong> fee structure was perceived by the community to be reasonable. <strong>The</strong>y also appreciatedthe well-equipped computer lab. <strong>The</strong> Sunni households noted the sectarian (Shia) orientation <strong>of</strong> theschools (parents asked to sign release forms), but they were content with the education and satisfied withcounter<strong>in</strong>g the sectarian <strong>in</strong>fluence via religious education at home. <strong>The</strong> NGO exercised good oversight,although excess demand had started result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> over-crowd<strong>in</strong>g. Nonetheless, the parents noted thetremendous progress made by their children s<strong>in</strong>ce they had been shifted to this school.<strong>The</strong> five successful Hira schools run by the Tanzeem-e-Asatza, were <strong>in</strong>dividualized. <strong>The</strong>re seemed to beno overarch<strong>in</strong>g organizational presence <strong>of</strong> the parent NGO perform<strong>in</strong>g the supervisory role. <strong>The</strong> teachers<strong>in</strong> some schools were not highly qualified but were dedicated and managed to <strong>in</strong>fuse confidence <strong>in</strong> thestudents who were well dressed and well behaved. By contrast to the crowded rented build<strong>in</strong>gs and poorlyqualified teachers <strong>of</strong> some schools, others had spacious and well-equipped classes and highly qualifiedand hard work<strong>in</strong>g teachers.<strong>The</strong> poor parents felt p<strong>in</strong>ched by the fees that the school adm<strong>in</strong>istration said was necessary to recoverrecurrent expenditures. In one school, poor students were allowed to attend free and the communitycontributed for scholarships for very poor deserv<strong>in</strong>g students. In another, an elaborate fee structure wasadopted to accommodate the poor students. Some parents nonetheless compla<strong>in</strong>ed about the high fees.Two <strong>of</strong> the three partners runn<strong>in</strong>g one school, orig<strong>in</strong>ally started as a “for pr<strong>of</strong>it” school, showed concernthat the school was not recover<strong>in</strong>g costs.<strong>The</strong> parents across the board were very supportive <strong>of</strong> the religious orientation <strong>of</strong> the schools. In thisregard, the schools could get away with poor delivery as <strong>in</strong>dicated by one Hira School described <strong>in</strong> thelast sub-section. Tameer-i-Millat (TM) is probably one <strong>of</strong> the best examples <strong>of</strong> such multi-schoolprograms that consistently produce good results. <strong>The</strong> parents supported this orientation, the religiouseducation and the efforts <strong>of</strong> the school to <strong>in</strong>culcate a moral outlook among the students.TM schools were well managed with the NGO play<strong>in</strong>g the role <strong>of</strong> a monitor and enforcer <strong>of</strong> standards.<strong>The</strong> schools build<strong>in</strong>gs were purpose built and hence had all the facilities necessary for good school<strong>in</strong>g.Compared to government schools, this meant that they were well lit, properly ventilated, had appropriatefurniture for the students and teachers and that the classes were <strong>of</strong> a comfortable size and not crowded.One comment about the students was that they were discipl<strong>in</strong>ed, self-confident and had a spark rare <strong>in</strong>rural schools. <strong>The</strong> teachers were motivated, aware, <strong>in</strong>volved, knew the parents and put <strong>in</strong> a great deal <strong>of</strong>effort.A systematic policy to curb absenteeism was observed. <strong>The</strong> students were admonished twice and, if thisdid not work, a letter was written to the parents to discuss the issue. Expulsion was ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed as the lastoption. <strong>The</strong>re was regular test<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> students to keep them <strong>in</strong>volved and alert. Extra periods wereobserved after school to provide special assistance for weak students.13