The structure and distribution of household wealth in Australia ...

The structure and distribution of household wealth in Australia ...

The structure and distribution of household wealth in Australia ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Social Policy Research Paper No. 33<strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong><strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>: cohort differences <strong>and</strong>retirement issuesBruce HeadeyDiana WarrenMark WoodenMelbourne Institute <strong>of</strong> Applied Economic <strong>and</strong> Social ResearchUniversity <strong>of</strong> MelbourneImprov<strong>in</strong>g the lives <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>ns

© Common<strong>wealth</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> 2008ISSN 1833-4369ISBN 978-1-921380-61-7This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may bereproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Common<strong>wealth</strong> available from theCommon<strong>wealth</strong> Copyright Adm<strong>in</strong>istration, Attorney-General’s Department. Requests <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>quiries concern<strong>in</strong>greproduction <strong>and</strong> rights should be addressed to the Common<strong>wealth</strong> Copyright Adm<strong>in</strong>istration,Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton, ACT 2600 or posted athttp://www.ag.gov.au/cca.<strong>The</strong> op<strong>in</strong>ions, comments <strong>and</strong>/or analysis expressed <strong>in</strong> this document are those <strong>of</strong> the authors <strong>and</strong> do notnecessarily represent the views <strong>of</strong> the M<strong>in</strong>ister for Families, Hous<strong>in</strong>g, Community Services <strong>and</strong> Indigenous Affairsor the <strong>Australia</strong>n Government Department <strong>of</strong> Families, Hous<strong>in</strong>g, Community Services <strong>and</strong> Indigenous Affairs(FaHCSIA), <strong>and</strong> cannot be taken <strong>in</strong> any way as expressions <strong>of</strong> Government policy.<strong>The</strong> study uses the confidentialised unit record file from the Household, Income <strong>and</strong> Labour Dynamics <strong>in</strong><strong>Australia</strong> (HILDA) survey. <strong>The</strong> HILDA Project was <strong>in</strong>itiated <strong>and</strong> is funded by FaHCSIA <strong>and</strong> is managed by theMelbourne Institute <strong>of</strong> Applied Economic <strong>and</strong> Social Research (MIAESR). <strong>The</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> views reported <strong>in</strong> thispaper are exclusively those <strong>of</strong> the authors <strong>and</strong> should not be attributed to the MIAESR.Refereed publicationSubmissions to the department’s Social Policy Research Paper series are subject to a bl<strong>in</strong>d peer review.Acknowledgements<strong>The</strong> research reported on <strong>in</strong> this paper was completed under FaHCSIA’s Social Policy Research Servicesagreement (2001–04) with the Melbourne Institute <strong>of</strong> Applied Economic <strong>and</strong> Social Research.Adm<strong>in</strong>istrative Arrangements Orders changesIn December 2007, Adm<strong>in</strong>istrative Arrangements Orders were announced that created a new Department <strong>of</strong>Families, Hous<strong>in</strong>g, Community Services <strong>and</strong> Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) to replace the former Department <strong>of</strong>Families, Community Services <strong>and</strong> Indigenous Affairs (FaCSIA). <strong>The</strong> former acronym (FaCSIA) has been usedwhere appropriate to refer to activities <strong>of</strong> the previous department.For more <strong>in</strong>formationResearch Publications UnitResearch <strong>and</strong> Analysis Branch<strong>Australia</strong>n Government Department <strong>of</strong> Families, Hous<strong>in</strong>g, Community Services <strong>and</strong> Indigenous AffairsBox 7788Canberra Mail Centre ACT 2610Phone: (02) 6244 5458Fax: (02) 6244 6589Email: publications.research@fahcsia.gov.au

CONTENTSContentsExecutive summaryv1 Introduction 11.1 Aims 11.2 Why <strong>wealth</strong> matters <strong>and</strong> why it makes sense to th<strong>in</strong>k <strong>of</strong> it as a long-term ‘stock’ 21.3 <strong>Australia</strong>n data <strong>and</strong> research on <strong>wealth</strong> prior to HILDA 22 Methods 52.1 <strong>The</strong> HILDA <strong>wealth</strong> module 2002 52.2 Measur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>wealth</strong> 52.3 Benchmark<strong>in</strong>g HILDA <strong>wealth</strong> estimates: comparisons with estimates <strong>in</strong> ABS <strong>and</strong> RBA publications 63 F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs 113.1 Introduction 113.2 <strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong>/composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> 113.3 <strong>The</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> 133.4 Retirement issues 163.5 Vulnerable groups <strong>in</strong> society 213.6 Determ<strong>in</strong>ants <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> 234 Conclusions <strong>and</strong> future research needs 29Appendix A: HILDA <strong>household</strong>-level <strong>wealth</strong> derived variables 31Appendix B: Assets <strong>and</strong> debts tables 33Endnotes 37References 39iii

<strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>List <strong>of</strong> tablesTable 1: Aggregate <strong>wealth</strong> sources, summary <strong>of</strong> differences <strong>in</strong> scope 6Table 2: Overview: assets, debts <strong>and</strong> net worth <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s <strong>in</strong> 2002, population weighted estimates 12Table 3: <strong>The</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>come, G<strong>in</strong>i coefficients 14Table 4: Shares <strong>of</strong> total <strong>wealth</strong> (net worth) by deciles 14Table 5: Age cohorts, net worth <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s at the cohort mean <strong>and</strong> at the 10th, 30th, median,70th <strong>and</strong> 90th percentiles 15Table 6: F<strong>in</strong>ancial assets <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>comes <strong>of</strong> retired couple home owners, cohorts aged 60–64, 65–69,70–74 <strong>and</strong> 75+, population weighted results 18Table 7: Projected f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>come, retirement at 60 or 65, population weighted results 19Table 8: F<strong>in</strong>ancial assets <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>comes <strong>of</strong> couple renter <strong>household</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>household</strong>s headedby non‐partnered people, population weighted results 20Table 9: Assets <strong>and</strong> debts <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>come support recipients, <strong>household</strong> reference person receiv<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>come support <strong>and</strong> not retired 22Table 10: <strong>The</strong> assets <strong>and</strong> debts <strong>of</strong> lone-parent <strong>household</strong>s 23Table 11: Households headed by persons aged 25 to 54, account<strong>in</strong>g for differences <strong>in</strong> net worth,OLS regressions 25Table 12: Households headed by persons aged 55 to 64 <strong>and</strong> not retired, account<strong>in</strong>g for differences<strong>in</strong> net worth, OLS regressions 26Table 13: Households headed by persons aged 55 to 64 <strong>and</strong> retired, account<strong>in</strong>g for differences<strong>in</strong> net worth, OLS regressions 27Table 14: Retirement age <strong>household</strong>s, account<strong>in</strong>g for differences <strong>in</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>, OLS regressions 28Appendix tablesTable B1: <strong>The</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>of</strong> cohorts, <strong>household</strong> reference person aged 15 to 24, population weighted estimates 33Table B2: <strong>The</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>of</strong> cohorts, <strong>household</strong> reference person aged 25 to 34, population weighted estimates 34Table B3: <strong>The</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>of</strong> cohorts, <strong>household</strong> reference person aged 35 to 44, population weighted estimates 35iv Social Policy Research Paper No. 33

Executive summaryExecutive summaryIn 2002, the first large-scale survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce World War I was undertaken as part<strong>of</strong> Wave 2 <strong>of</strong> the Household, Income <strong>and</strong> Labour Dynamics <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> (HILDA) survey. <strong>The</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> data obta<strong>in</strong>ed<strong>in</strong> the survey (from 7,245 <strong>household</strong>s) covered all the ma<strong>in</strong> components <strong>of</strong> asset portfolios <strong>and</strong> debts. <strong>The</strong> datawere found to match satisfactorily with national aggregate statistics available from the <strong>Australia</strong>n Bureau <strong>of</strong>Statistics <strong>and</strong> the Reserve Bank <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>.<strong>The</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> this paper is to analyse the 2002 HILDA <strong>wealth</strong> module data under a number <strong>of</strong> head<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g:ªªªªªthe <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> debt <strong>and</strong> whether this has changed <strong>in</strong> recent yearsthe <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g among <strong>and</strong> with<strong>in</strong> age cohorts <strong>and</strong> the most <strong>and</strong> least <strong>wealth</strong>y cohortsretirement issues, focus<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> particular on the capacity <strong>of</strong> pre <strong>and</strong> post-retirement cohorts for self-fund<strong>in</strong>gdur<strong>in</strong>g retirementthe <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> debt levels <strong>of</strong> vulnerable groups <strong>in</strong> society, especially <strong>in</strong>come support recipients <strong>and</strong> loneparentsthe ma<strong>in</strong> factors (demographic, educational, <strong>in</strong>come related, <strong>and</strong> so on) which determ<strong>in</strong>e levels <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong>debt.Analysis <strong>of</strong> the HILDA data shows that asset hold<strong>in</strong>gs are heavily concentrated <strong>in</strong> the h<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> older<strong>household</strong>s—those with<strong>in</strong> 20 years <strong>of</strong> retirement <strong>and</strong> those 10 to 15 years post retirement. This <strong>distribution</strong> isdue ma<strong>in</strong>ly to the fact that asset levels depend on the length <strong>of</strong> time spent sav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> benefit<strong>in</strong>g from the effects<strong>of</strong> compound <strong>in</strong>terest. It is also a consequence <strong>of</strong> government policy <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiatives such as the SuperannuationGuarantee <strong>and</strong> generous tax concessions to encourage retirement sav<strong>in</strong>gs.Superannuation hold<strong>in</strong>gs are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g rapidly <strong>and</strong> are now more widely distributed than <strong>in</strong> the past. However,the evidence <strong>in</strong> this report shows that most <strong>household</strong>s with<strong>in</strong> 20 years <strong>of</strong> retirement are likely to be partlyreliant on the Age Pension for their retirement <strong>in</strong>come. Current government policy is tackl<strong>in</strong>g this problem bychang<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>centives affect<strong>in</strong>g both the age at which people choose to retire <strong>and</strong> their likelihood <strong>of</strong> do<strong>in</strong>g somepaid work dur<strong>in</strong>g retirement. It rema<strong>in</strong>s to be seen how effective these changes will be <strong>in</strong> counteract<strong>in</strong>g theevident desire <strong>of</strong> most <strong>Australia</strong>ns to retire before age 65. A serious underly<strong>in</strong>g problem is that most work<strong>in</strong>g-agepeople cont<strong>in</strong>ue to underestimate the sav<strong>in</strong>gs they will need to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> their current lifestyle <strong>in</strong> retirement.<strong>The</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> assets types <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>household</strong>s are hous<strong>in</strong>g, equities <strong>and</strong> superannuation. Given the volatility <strong>in</strong>the value <strong>of</strong> these assets <strong>in</strong> recent times, it is probably mistaken to believe that <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> is fairly stable.In the context <strong>of</strong> an age<strong>in</strong>g population, we need a better underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the dynamics <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>, particularlyfor those <strong>in</strong> the retirement <strong>and</strong> pre-retirement cohorts. This means it will be important to measure <strong>household</strong><strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> assess the causes <strong>and</strong> consequences <strong>of</strong> change more frequently than <strong>in</strong> the past.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>vi Social Policy Research Paper No. 33

INTRODUCTION1 Introduction1.1 AimsThis report is <strong>in</strong>tended to contribute to an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>.More particularly, it relates to the extent to which mature-age <strong>Australia</strong>ns now have, <strong>and</strong> may have <strong>in</strong> the future,a capacity for f<strong>in</strong>ancial self-reliance dur<strong>in</strong>g retirement.<strong>The</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> this report is to analyse the <strong>wealth</strong> module <strong>in</strong> the 2002 Household Income <strong>and</strong> Labour Dynamics <strong>in</strong><strong>Australia</strong> (HILDA) survey <strong>in</strong> order to address the follow<strong>in</strong>g issues.Structure/composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> debtIssue 1What are the ma<strong>in</strong> components <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> debt? What are the relative shares <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets <strong>and</strong>non‐f<strong>in</strong>ancial (particularly hous<strong>in</strong>g) assets?Issue 2Has the level <strong>and</strong> composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> changed <strong>in</strong> recent years? If so, to what extent have <strong>in</strong>creasesbeen due to possibly transient <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> hous<strong>in</strong>g values?<strong>The</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>Issue 3aWhat is the overall <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>?Issue 3bHow are <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>debtedness distributed among age cohorts? How wide is the gap between the most <strong>and</strong>least <strong>wealth</strong>y cohorts? How is <strong>wealth</strong> distributed with<strong>in</strong> cohorts?Retirement issuesIssue 4aRetirement—focus<strong>in</strong>g on the older age cohorts (those aged 45 years <strong>and</strong> over), what is their capacity forself‐fund<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> retirement?Issue 4bIs there a relationship between <strong>in</strong>tended age <strong>of</strong> retirement <strong>and</strong> levels <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> debt?Vulnerable groups <strong>in</strong> societyIssue 5How do vulnerable <strong>and</strong> ‘at risk’ groups fare <strong>in</strong> regard to <strong>wealth</strong>? In particular, what are the assets <strong>and</strong> debts <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>come support recipients? What is the <strong>wealth</strong> situation <strong>of</strong> lone parents?

<strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>Determ<strong>in</strong>ants <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>Issue 6What are the ma<strong>in</strong> factors (demographic, educational, <strong>in</strong>come related, <strong>and</strong> so on) which determ<strong>in</strong>e levels <strong>of</strong><strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> debt?1.2 Why <strong>wealth</strong> matters <strong>and</strong> why it makes sense to th<strong>in</strong>k <strong>of</strong> it as along-term ‘stock’Before address<strong>in</strong>g these issues directly, it may be useful to ask why <strong>wealth</strong> matters. How does it contribute to a<strong>household</strong>’s economy <strong>and</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> life <strong>and</strong> what are the implications <strong>of</strong> see<strong>in</strong>g <strong>wealth</strong> as a long-term ‘stock’?Wealth confers economic security, <strong>and</strong> this is a high priority for many people. It enables a <strong>household</strong> to tide overbad times due to, for example, unemployment or ill health, when the normal flow <strong>of</strong> earned <strong>in</strong>come is reduced orcut <strong>of</strong>f. Wealth also enables a <strong>household</strong> to ga<strong>in</strong> access to credit so it can borrow either to tide over bad times, or<strong>in</strong>vest for the future by, for example, pay<strong>in</strong>g for education, or buy<strong>in</strong>g property, shares or a bus<strong>in</strong>ess. Wealth alsodirectly generates <strong>in</strong>come both <strong>in</strong> cash <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d; for example, shares <strong>and</strong> superannuation hold<strong>in</strong>gs directlygenerate cash <strong>in</strong>come. Equally valuably, owner-occupied hous<strong>in</strong>g or art works or other collectibles <strong>in</strong> the homeprovide benefits <strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d. <strong>The</strong>y contribute to a <strong>household</strong>’s quality <strong>of</strong> life <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>of</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g broadly def<strong>in</strong>ed.In the context <strong>of</strong> this report, a key aspect <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> is that it can provide security <strong>and</strong> even comfort <strong>in</strong> one’sretirement years.It makes sense for <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>and</strong> <strong>household</strong>s to th<strong>in</strong>k about <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> the long term, not just the short term. Ineconomic or account<strong>in</strong>g terms <strong>wealth</strong> is a ‘stock’, whereas <strong>in</strong>come is a ‘flow’. Households act<strong>in</strong>g rationally th<strong>in</strong>kabout build<strong>in</strong>g up their <strong>wealth</strong> over members’ work<strong>in</strong>g lives. <strong>The</strong>n, <strong>in</strong> retirement, members use their accumulatedsav<strong>in</strong>gs to enjoy a satisfy<strong>in</strong>g st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>of</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> life.A corollary <strong>of</strong> the long-term nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g is that it is sometimes sensible for <strong>household</strong>s to <strong>in</strong>curdebts so they can <strong>in</strong>vest <strong>and</strong> build up their assets <strong>in</strong> the long term. In the short term, a <strong>household</strong> mightrationally choose to reduce its net worth (assets m<strong>in</strong>us debts) <strong>in</strong> order to achieve long-term ga<strong>in</strong>s. A <strong>household</strong>approach<strong>in</strong>g retirement may, for example, borrow aga<strong>in</strong>st the equity <strong>in</strong> its home to buy shares or managedfunds, know<strong>in</strong>g that it will consequently, for some years to come, have both high asset levels <strong>and</strong> high debts.We shall see throughout this report that high assets <strong>and</strong> high debts go together. <strong>The</strong> more assets you have, thebetter your credit rat<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>and</strong> the more you are likely to borrow. Debts <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>vestments are, <strong>of</strong> course, <strong>of</strong>ten thesame th<strong>in</strong>g.Partly because <strong>of</strong> these considerations, we use a range <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> measures <strong>in</strong> this report, rather than a s<strong>in</strong>glesummary measure. We consistently use net worth as a summary measure, but we also report <strong>household</strong> assets<strong>and</strong> debts separately <strong>in</strong> most tables, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten components <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets <strong>and</strong> non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets.F<strong>in</strong>ancial assets <strong>in</strong>clude superannuation, <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>in</strong> shares <strong>and</strong> other equities, cash-type <strong>in</strong>vestments <strong>and</strong>bank accounts. Non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets <strong>in</strong>clude hous<strong>in</strong>g, bus<strong>in</strong>esses <strong>and</strong> vehicles.1.3 <strong>Australia</strong>n data <strong>and</strong> research on <strong>wealth</strong> prior to HILDAIn 1915, faced with <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g wartime expenditure, the <strong>Australia</strong>n Government used the Census to measure the<strong>wealth</strong> <strong>of</strong> the five million or so <strong>Australia</strong>ns liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the country at the time. As it turned out, nearly 90 per cent <strong>of</strong>all <strong>wealth</strong> was owned by the richest 10 per cent <strong>of</strong> the population.<strong>The</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> module <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the second wave <strong>of</strong> HILDA <strong>in</strong> 2002 is the first large-scale survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong><strong>wealth</strong> (n=7,245 <strong>household</strong>s) conducted s<strong>in</strong>ce the 1915 Census. <strong>The</strong> module was designed jo<strong>in</strong>tly by the ReserveBank <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> (RBA) <strong>and</strong> the Melbourne Institute <strong>of</strong> Applied Economic <strong>and</strong> Social Research (MelbourneInstitute). <strong>The</strong> questions covered all ma<strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g bank accounts, superannuation <strong>and</strong> shares,<strong>and</strong> all ma<strong>in</strong> non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g hous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>esses, together with the ma<strong>in</strong> categories <strong>of</strong> debt. Social Policy Research Paper No. 33

<strong>in</strong>troductionBecause this was a <strong>household</strong> survey, rather than an estimate <strong>of</strong> national aggregate <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>of</strong> the k<strong>in</strong>d publishedregularly by the <strong>Australia</strong>n Bureau <strong>of</strong> Statistics (ABS), it enables us to focus on <strong>distribution</strong>al issues <strong>and</strong> cohortdifferences—that is, the differ<strong>in</strong>g asset portfolios <strong>of</strong> richer <strong>and</strong> poorer <strong>household</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> different age cohorts.<strong>The</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> data series available from the ABS do not deal with <strong>distribution</strong>al issues. <strong>The</strong>y provide quarterlyestimates <strong>of</strong> national aggregate <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> (ABS cat. no. 5232.0). 1 <strong>The</strong> value <strong>of</strong> some non-f<strong>in</strong>ancialassets, pr<strong>in</strong>cipally hous<strong>in</strong>g but not un<strong>in</strong>corporated bus<strong>in</strong>esses, are estimated <strong>in</strong> the National Accounts(ABS cat. no. 5204.0). In general terms, government agencies (such as the ABS <strong>and</strong> the RBA) do not measure<strong>household</strong> sector assets directly, but rather treat them as residuals after subtract<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess sector assets(about which much is known) from national estimates <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>. Even so, while exist<strong>in</strong>g sources probablyprovide accurate estimates <strong>of</strong> changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> over time, they tell us little about distributive issues.Most previous estimates <strong>of</strong> the <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> have been based on <strong>in</strong>ferr<strong>in</strong>g stocks (assets)from flows (<strong>in</strong>come). For example, <strong>in</strong>come from bus<strong>in</strong>ess ownership <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>come from share dividends haveto be declared on tax returns <strong>and</strong> can be used to estimate asset values. <strong>The</strong> National Centre for Social <strong>and</strong>Economic Modell<strong>in</strong>g (NATSEM) has used this approach to provide <strong>household</strong> estimates (Baekgaard 1998; Kelly2001, 2003), as has the ABS (Robertson, Gr<strong>and</strong>y & McEw<strong>in</strong> 2000; Northwood, Rawnsley & Chen 2002).Apart from the 1915 Census, there appears to have been just one small-scale <strong>Australia</strong>n survey <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong><strong>wealth</strong> conducted <strong>in</strong> 1967 (Podder & Kakwani 1976). This was valuable but it omitted farmers <strong>and</strong>, partly due tothis omission, may have understated <strong>in</strong>equality <strong>of</strong> net worth (Kelly 2001).<strong>The</strong> next chapter gives an overview <strong>of</strong> the HILDA <strong>wealth</strong> module <strong>and</strong> the ma<strong>in</strong> measures used. HILDA’s <strong>wealth</strong>estimates are compared with the ABS <strong>and</strong> RBA national aggregates.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> Social Policy Research Paper No. 33

METHODS2 Methods2.1 <strong>The</strong> HILDA <strong>wealth</strong> module 2002A <strong>wealth</strong> module was <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the second wave <strong>of</strong> HILDA <strong>in</strong> 2002. Described <strong>in</strong> more detail <strong>in</strong> Watson <strong>and</strong>Wooden (2002), HILDA is a <strong>household</strong> panel survey conducted under contract to the <strong>Australia</strong>n GovernmentDepartment <strong>of</strong> Families, Community Services <strong>and</strong> Indigenous Affairs (FaCSIA) by the Melbourne Institute atthe University <strong>of</strong> Melbourne. It began <strong>in</strong> 2001 with a large, national, representative sample <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>volved personal <strong>in</strong>terviews with all <strong>household</strong> members aged 15 <strong>and</strong> over. In Wave 1, <strong>in</strong>terviews were obta<strong>in</strong>edfrom 7,682 <strong>household</strong>s, which represented 66 per cent <strong>of</strong> all <strong>household</strong>s identified as <strong>in</strong> scope. This <strong>in</strong> turngenerated a sample <strong>of</strong> 15,127 persons eligible for <strong>in</strong>terview, 13,969 <strong>of</strong> whom were successfully <strong>in</strong>terviewed.<strong>The</strong> survey’s coverage is extremely broad, but focuses on <strong>household</strong> <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> formation, <strong>in</strong>come <strong>and</strong>economic wellbe<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> employment <strong>and</strong> labour force participation. Each year a special module <strong>of</strong> non-corequestions is added. In Wave 1, it was appropriate to devote the module to personal <strong>and</strong> family history. In Wave 2,the topic was <strong>wealth</strong>, with the module be<strong>in</strong>g funded <strong>in</strong> large part by the RBA.In 2002 all respond<strong>in</strong>g <strong>household</strong>s from Wave 1 were re-contacted. Interviews were aga<strong>in</strong> sought with all<strong>household</strong> members aged 15 or over, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g persons who did not respond <strong>in</strong> Wave 1, as well as any new<strong>household</strong> members. In total, <strong>in</strong>terviews were completed with 13,041 persons from 7,245 <strong>household</strong>s. Of thisgroup, almost 12,000 were respondents from Wave 1, which represented almost 87 per cent <strong>of</strong> the Wave 1<strong>in</strong>dividual sample. Like all surveys, the HILDA survey has sampl<strong>in</strong>g errors—differences between the sample’scharacteristics <strong>and</strong> population Census characteristics. <strong>The</strong> data <strong>in</strong>clude weights to adjust for these biases.2.2 Measur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>wealth</strong><strong>The</strong> HILDA <strong>wealth</strong> module was designed jo<strong>in</strong>tly by the RBA <strong>and</strong> the Melbourne Institute. Most <strong>of</strong> the questionsabout assets <strong>and</strong> debts were asked at the <strong>household</strong> level <strong>and</strong> answered by one person on behalf <strong>of</strong> theentire <strong>household</strong>. <strong>The</strong> questions covered hous<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>and</strong> un<strong>in</strong>corporated bus<strong>in</strong>esses, equity-type<strong>in</strong>vestments (for example, shares, managed funds) <strong>and</strong> cash-type <strong>in</strong>vestments (for example, bonds, debentures),<strong>and</strong> vehicles <strong>and</strong> collectibles (for example, art works). However, <strong>in</strong>dividuals were asked some questions aboutassets <strong>and</strong> debts, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g superannuation, bank accounts, credit cards, student debt (Higher EducationContribution Scheme—HECS) <strong>and</strong> other personal debt. Respondents were asked to give exact dollar amountswhen answer<strong>in</strong>g all questions. However, b<strong>and</strong>s were <strong>of</strong>fered to those who could not provide an exact estimate <strong>of</strong>their superannuation hold<strong>in</strong>gs—a particularly difficult topic. (Appendix A presents a diagram show<strong>in</strong>g how thecomponents <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> measured <strong>in</strong> HILDA have been aggregated.)Wealth is not easy to measure <strong>in</strong> surveys <strong>and</strong>, when attempted overseas, has been associated with high itemnon-response rates <strong>and</strong> substantial underestimates <strong>in</strong> measur<strong>in</strong>g aggregate national <strong>wealth</strong>, if the NationalAccounts are taken as a benchmark (Juster, Smith & Stafford 1999). This last result is largely due to the fact thatthe <strong>wealth</strong>iest 2 per cent or so <strong>of</strong> the population, who own a vastly disproportionate share <strong>of</strong> the <strong>wealth</strong>, are<strong>in</strong>variably underrepresented <strong>in</strong> surveys.<strong>The</strong> HILDA survey was not immune from these difficulties. It achieved response rates <strong>of</strong> more than 90 per centfor almost all components <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>, but 39 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s could not provide <strong>in</strong>formation about atleast one component. Not surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, many could not specify their superannuation or bus<strong>in</strong>ess hold<strong>in</strong>gs.So we were only able to directly compute net <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> for 61 per cent <strong>of</strong> respond<strong>in</strong>g <strong>household</strong>s.Statistical imputations <strong>of</strong> miss<strong>in</strong>g data were undertaken by the RBA. This was essential, s<strong>in</strong>ce to omit caseswith miss<strong>in</strong>g data would have <strong>in</strong>troduced a bias aga<strong>in</strong>st larger <strong>household</strong>s <strong>in</strong> which it is harder to get everyeligible respondent to participate. So the HILDA files used <strong>in</strong> this report now conta<strong>in</strong> complete <strong>wealth</strong> data for all7,245 <strong>household</strong>s <strong>in</strong>terviewed at Wave 2, with flags to <strong>in</strong>dicate where imputations have been made.

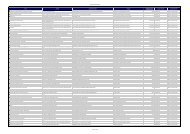

<strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>2.3 Benchmark<strong>in</strong>g HILDA <strong>wealth</strong> estimates: comparisons withestimates <strong>in</strong> ABS <strong>and</strong> RBA publicationsIn assess<strong>in</strong>g currently available data it is usually helpful to have <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d what an ideal data set would look like.In measur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>wealth</strong>, then, we ideally want to measure the market value <strong>of</strong> all assets <strong>and</strong> debts. This is whatHILDA tried to do. Alternative measures exist <strong>and</strong> are, <strong>in</strong> some cases, used by government agencies as proxiesfor market value. An example is use <strong>of</strong> the book (tangible assets) value <strong>of</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess assets. This measure has theadvantage <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g reliable <strong>in</strong> the sense that it is replicable with a low marg<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> error. But, if it is substantiallydifferent from market value (which it probably is—see below), then it is not a valid measure; that is, it is notmeasur<strong>in</strong>g the ‘right’ th<strong>in</strong>g, but someth<strong>in</strong>g else. Officials <strong>in</strong> government agencies who use proxy measures arepresumably aware <strong>of</strong> the validity limitations <strong>of</strong> such measures, but the measures are quite <strong>of</strong>ten cited by othersas if they were <strong>in</strong>disputably valid. A key po<strong>in</strong>t about measurement is that measures cannot be valid unless theyare reasonably reliable, but they can be totally reliable <strong>and</strong> have no validity at all.To benchmark the HILDA data we compare its estimates <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> assets, debts <strong>and</strong> net worth with thenational aggregates available from the ma<strong>in</strong> ABS <strong>and</strong> associated sources. <strong>The</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> published sources are:(1) the ABS <strong>Australia</strong>n System <strong>of</strong> National Accounts (cat. no. 5204.0), which needs to be read <strong>in</strong> conjunctionwith the ABS F<strong>in</strong>ancial Accounts (cat. no. 5232.0)(2) RBA Statement on Monetary Policy (various dates). 2As a first step <strong>in</strong> benchmark<strong>in</strong>g, Table 1 shows which components <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets, non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets <strong>and</strong>debts are reported <strong>in</strong> HILDA <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the government sources.Table 1:Aggregate <strong>wealth</strong> sources, summary <strong>of</strong> differences <strong>in</strong> scopeAsset type HILDA ABS RBAF<strong>in</strong>ancial assetsDeposits ¸ ¸ ¸Bonds etc. ¸ ¸ ¸Equities ¸ ¸ ¸Unfunded superannuation ¸ ¸ œPre-paid <strong>in</strong>surance premiums œ ¸ œNon-f<strong>in</strong>ancial assetsVehicles ¸ ¸ ¸Other consumer durables œ ¸ ¸Hous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> property ¸ ¸ ¸Bus<strong>in</strong>ess assets ¸ ¸ œCollectibles ¸ œ œDebtsHous<strong>in</strong>g debt ¸ ¸ ¸Bus<strong>in</strong>ess debt ¸ ¸ ¸Student debt (HECS) ¸ ¸ ¸Credit card debt ¸ ¸ ¸Other personal debt ¸ ¸ ¸Note: ¸ <strong>in</strong>dicates that the component is <strong>in</strong>cluded by HILDA, ABS or RBA, while œ <strong>in</strong>dicates it is not.Differences <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>and</strong> exclusion among the different sources mean that comparisons are notstraightforward. One immediate difference is that the ABS <strong>and</strong> RBA <strong>in</strong>clude the assets <strong>and</strong> liabilities <strong>of</strong>non‐pr<strong>of</strong>it organisations <strong>in</strong> the ‘<strong>household</strong> balance sheet’, whereas HILDA data relate strictly to <strong>household</strong>s. Social Policy Research Paper No. 33

METHODSNow consider the treatment <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets. We see that the ABS <strong>and</strong> the RBA only differ <strong>in</strong> how they treatunfunded superannuation <strong>and</strong> pre-paid <strong>in</strong>surance premiums—the RBA excludes them whereas the ABS doesnot. Conceptually the HILDA survey falls between the two, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g unfunded superannuation but exclud<strong>in</strong>gpre-paid <strong>in</strong>surance premiums. (It should be noted that the sums <strong>in</strong>volved here are quite small.) Turn<strong>in</strong>g tonon-f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets, Table 1 <strong>in</strong>dicates that HILDA measures collectibles whereas the government sources donot. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, HILDA does not measure the value <strong>of</strong> consumer durables (except vehicles), whereasthe government sources do. Both HILDA <strong>and</strong> the ABS value the assets <strong>of</strong> un<strong>in</strong>corporated bus<strong>in</strong>esses owned by<strong>household</strong>s, but the RBA leaves them out.Let us now compare dollar amounts for assets <strong>and</strong> debts estimated by HILDA <strong>and</strong> the government sources.Estimates for HILDA <strong>and</strong> the ABS relate to an average <strong>of</strong> the September 2002 <strong>and</strong> December 2002 quarters,which is when most <strong>of</strong> the HILDA <strong>in</strong>terview<strong>in</strong>g was conducted. <strong>The</strong> RBA data are for the December quarter.Note that the HILDA estimates <strong>of</strong> mean asset <strong>and</strong> debt values, which were obta<strong>in</strong>ed on a <strong>household</strong> basis, weremultiplied by the number <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the country to obta<strong>in</strong> comparisons with the national aggregatesprovided by the government sources.F<strong>in</strong>ancial assetsFirst, we consider f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets. As noted above, conceptually HILDA falls between the two governmentsources by <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g unfunded superannuation but exclud<strong>in</strong>g pre-paid <strong>in</strong>surance premiums. It transpires that,empirically, the HILDA estimate also lies between the government estimates:HILDA: $1,125 billionABS:RBA:$1,237 billion$1,084 billionIf we adjust the HILDA data by add<strong>in</strong>g the ABS estimate <strong>of</strong> pre-paid <strong>in</strong>surance premiums—just over $28 billion—we f<strong>in</strong>d that the HILDA estimate is about 93 per cent <strong>of</strong> the ABS estimate. Thus, as expected, HILDA understatesthe volume <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets. <strong>The</strong> size <strong>of</strong> that understatement, however, is relatively modest.Non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial assetsNext, we consider non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets, the area <strong>in</strong> which it is most difficult to make well-matched comparisons.Hous<strong>in</strong>g is by far the biggest component, followed by bus<strong>in</strong>ess assets. At first exam<strong>in</strong>ation, the three sourcesseem far apart on hous<strong>in</strong>g:HILDA: $1,932 billionABS:RBA:$1,597 billion$2,252 billionIn large part the explanation for these discrepancies lies <strong>in</strong> different methods <strong>of</strong> measurement/estimation. <strong>The</strong>HILDA survey asked respondents who completed the Household Questionnaire (nearly always the <strong>household</strong>reference person or his/her partner) to estimate the market value <strong>of</strong> their property if sold today. <strong>The</strong>re is strong<strong>Australia</strong>n evidence that <strong>household</strong>ers can estimate their own property values with reasonable accuracy—onaverage they get with<strong>in</strong> 3 per cent <strong>of</strong> the ‘correct’ valuation as determ<strong>in</strong>ed by pr<strong>of</strong>essional real estate valuers(Yates 1991). <strong>The</strong> ABS adopts a quite different approach. A perpetual <strong>in</strong>ventory model is used to estimatethe dwell<strong>in</strong>g stock, allowance is made for new build<strong>in</strong>g activity, <strong>and</strong> values are obta<strong>in</strong>ed from the Hous<strong>in</strong>gIndustry Association (HIA)/Common<strong>wealth</strong> Bank <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> (CBA) house price series (Northwood, Rawnsley& Chen 2002). <strong>The</strong> RBA does th<strong>in</strong>gs somewhat differently: it ‘… splices together the quarterly HIA/CBA medianprice series <strong>and</strong> the Real Estate Institute <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> (REIA) median price series for each state’ (Northwood,Rawnsley & Chen 2002, p. 53). <strong>The</strong> different methods used by the two government organisations produce widelydivergent results <strong>and</strong> there is some evidence that, over time, the gap is gett<strong>in</strong>g wider. Northwood, Rawnsley <strong>and</strong>

METHODSOn this basis it appears that the HILDA estimate is 98 per cent <strong>of</strong> the RBA figure <strong>and</strong> 134 per cent <strong>of</strong> the ABSfigure. <strong>The</strong> differences, as expla<strong>in</strong>ed above, are primarily due to the use <strong>of</strong> different methods <strong>of</strong> valu<strong>in</strong>g bothhous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>esses.Overall, <strong>in</strong> estimat<strong>in</strong>g total assets (f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>and</strong> non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial comb<strong>in</strong>ed), we are pleasantly surprised thatHILDA appears not to be substantially under the mark. While gratify<strong>in</strong>g, this is someth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> a puzzle giventhe more‐or‐less unavoidable underrepresentation <strong>of</strong> the very <strong>wealth</strong>y. <strong>The</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>iest <strong>household</strong> <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong>the HILDA sample, for example, had a reported net worth <strong>of</strong> $22 million, well below the levels recorded for<strong>in</strong>dividuals listed <strong>in</strong> the Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Review Weekly’s list <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>’s 200 <strong>wealth</strong>iest people (Bus<strong>in</strong>ess ReviewWeekly 2004).Debts<strong>The</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al comparisons we discuss <strong>in</strong> this chapter relate to debts. Comparability among the three data sets hereis much greater, so we can reasonably just review total debt estimates rather than discuss each componentseparately.HILDA: $517 billionABS:RBA:$631 billionsame data as ABSHere the HILDA estimate is only 82 per cent <strong>of</strong> the ABS figure. In retrospect, we suspect the HILDA questionnairemay not have <strong>in</strong>cluded enough questions on separate types <strong>of</strong> debt. As noted above <strong>in</strong> Table 1, HILDA split<strong>household</strong> debt <strong>in</strong>to five categories: hous<strong>in</strong>g debt, bus<strong>in</strong>ess debt, student debt (HECS), credit card debt <strong>and</strong>‘other’ personal debt. It might have been preferable to ask specifically about overdrafts (exclud<strong>in</strong>g hous<strong>in</strong>g),vehicle debt, hire purchase, gambl<strong>in</strong>g debts <strong>and</strong> so on (see Juster, Smith & Stafford 1999). Even so, there may besome irreducible tendency for respondents to underreport debt, partly for social desirability reasons. We alsobelieve that, relative to <strong>of</strong>ficial sources, credit card debt will be understated <strong>in</strong> HILDA. Those respondents whosaid they rout<strong>in</strong>ely paid up <strong>in</strong> the first month <strong>and</strong> so <strong>in</strong>curred no <strong>in</strong>terest charges were recorded as hav<strong>in</strong>g nocredit card debt. By contrast, the <strong>of</strong>ficial sources record credit card liabilities owed by the nation’s <strong>household</strong>s atone moment <strong>in</strong> time.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>10 Social Policy Research Paper No. 33

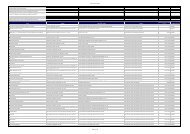

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs3 F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs3.1 IntroductionAll results are weighted to adjust for differences between sample <strong>and</strong> population characteristics. <strong>The</strong> resultscan thus be treated as population estimates, or as be<strong>in</strong>g weighted up from a sample size <strong>of</strong> 7,245 <strong>household</strong>sto a population size <strong>of</strong> 7,540,411 <strong>household</strong>s. Because this is a large sample the confidence <strong>in</strong>tervals for mostestimates given <strong>in</strong> this report are with<strong>in</strong> plus or m<strong>in</strong>us 3.5 per cent at a confidence level <strong>of</strong> 95 per cent. Ofcourse, where estimates <strong>of</strong> the <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>of</strong> smaller subsets <strong>of</strong> the population are given, they are less reliable.Estimates which would be too unreliable for most practical purposes because they have a st<strong>and</strong>ard error <strong>of</strong> morethan 50 per cent <strong>of</strong> the estimate have been marked ‘nr’ <strong>in</strong> the tables that follow.3.2 <strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong>/composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>Issue 1:What are the ma<strong>in</strong> components <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> debt? What are the relative shares <strong>of</strong>f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>and</strong> non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial (particularly hous<strong>in</strong>g) assets?Table 2 gives an overview <strong>of</strong> the <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>household</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the last quarter <strong>of</strong> 2002. 4 It gives mean <strong>and</strong>median assets <strong>and</strong> debts, <strong>and</strong> hence net worth, <strong>and</strong> also the percentage contribution which each type <strong>of</strong> asset<strong>and</strong> debt makes to total hold<strong>in</strong>gs. 5It should be noted that the medians reported <strong>in</strong> Table 2 (but not later tables) are somewhat unusual. <strong>The</strong> aimis to describe the <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>of</strong> the typical <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>household</strong>. So we report the median assets <strong>and</strong> debts <strong>of</strong><strong>household</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the 50 th (median) percentile <strong>of</strong> net worth. In other words, we take <strong>household</strong>s with overall <strong>wealth</strong>(net worth) that is ‘typical’ <strong>and</strong> then show their asset <strong>and</strong> debt levels. Because the <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> ishighly skewed, medians give a better idea <strong>of</strong> the typical <strong>household</strong>’s <strong>wealth</strong> than do means.In the last quarter <strong>of</strong> 2002, the average <strong>household</strong> had an estimated net worth <strong>of</strong> approximately $404,800($473,300 <strong>of</strong> assets <strong>and</strong> $68,500 <strong>of</strong> debts). However, these mean estimates are skewed upwards by <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>of</strong>the rich. <strong>The</strong> median <strong>household</strong> had assets <strong>of</strong> only about $288,000 <strong>and</strong> a net worth <strong>of</strong> about $218,600.As is well known, <strong>Australia</strong>ns’ asset portfolios are dom<strong>in</strong>ated by hous<strong>in</strong>g. Hous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> other property constitutemore than 50 per cent <strong>of</strong> all <strong>household</strong> assets <strong>and</strong> more than 60 per cent <strong>of</strong> the assets <strong>of</strong> the median <strong>household</strong>.Over two-thirds <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s—67.8 per cent—owned or were buy<strong>in</strong>g their own home. Quite a high proportion<strong>of</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>household</strong>s—16.7 per cent—had <strong>in</strong>vested <strong>in</strong> other property as well (a holiday home or <strong>in</strong>vestmentproperty).<strong>The</strong> second largest asset <strong>of</strong> most <strong>household</strong>s is superannuation, which has become much more widely held<strong>and</strong> somewhat more equally distributed <strong>in</strong> the last 15 years (Kelly 2001). Even so, the median <strong>household</strong>holds superannuation worth only about $17,000. Other hold<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> considerable value to some <strong>household</strong>sare bus<strong>in</strong>ess assets <strong>and</strong> equity <strong>in</strong>vestments (for example, shares, managed funds, listed property trusts). <strong>The</strong>median <strong>household</strong> holds no equities <strong>and</strong> does not own a bus<strong>in</strong>ess. However, the 41 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s thatdo own equities average about $70,000 worth (median=$15,000), <strong>and</strong> the average value <strong>of</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>esses (ownedby 13 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s) was about $291,000 (median=$80,000). It should be noted, however, that equity<strong>in</strong>vestments are understated here s<strong>in</strong>ce, <strong>in</strong> order to avoid double count<strong>in</strong>g, HILDA respondents were asked notto <strong>in</strong>clude superannuation <strong>in</strong> their calculation <strong>of</strong> equity hold<strong>in</strong>gs; <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> course some superannuation was held<strong>in</strong> equities. Mov<strong>in</strong>g then towards the bottom <strong>of</strong> the list <strong>of</strong> assets, the median <strong>household</strong> had vehicles worthabout $12,000 <strong>and</strong> $4,700 <strong>in</strong> the bank.Household debt is ma<strong>in</strong>ly mortgages. <strong>The</strong> average property debt is about $51,000. Most <strong>household</strong>s have littleor zero <strong>in</strong> other forms <strong>of</strong> debt.11

<strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>Table 2:Overview: assets, debts <strong>and</strong> net worth <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s <strong>in</strong> 2002, population weighted estimatesn=7,245 <strong>household</strong>sMean($’000)Median($’000)% total assetsor debts% <strong>household</strong>shold<strong>in</strong>gassets/debtsOverall assets <strong>and</strong> debtsTotal assets 473.3 288.0Total debts 68.5 10.0Net worth (assets m<strong>in</strong>us debts) 404.8 218.6Assets <strong>in</strong> order <strong>of</strong> valueHous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> other property 255.0 180.0 53.9 71.0 (a)Pensions/superannuation 75.2 17.0 15.9 77.0Bus<strong>in</strong>esses <strong>and</strong> farms 44.4 0 9.4 13.1Equity <strong>in</strong>vestments (shares, managed 31.3 0 6.6 41.4funds)Bank accounts 21.4 4.7 4.5 97.3Cars <strong>and</strong> other vehicles 19.0 12.0 4.0 87.9Other assets (b) (c) 27.9 0 5.9 47.4(100.0)Non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets 315.4 204.5 66.6 93.6F<strong>in</strong>ancial assets (c) 157.9 49.5 33.4 99.3(473.3) (100.0)Debts <strong>in</strong> order <strong>of</strong> valueHous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> other property 51.4 0 75.0 38.7Bus<strong>in</strong>esses <strong>and</strong> farms 6.8 0 9.9 5.2HECS (student) debt 1.3 0 1.9 12.7Credit (<strong>and</strong> similar) cards 1.1 0 1.6 39.5Other debts (cars, hire purchase etc.) (c) 7.9 0 11.5 36.7(68.5) (100.0)(a) 71.0 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s owned property; 67.7 per cent owned the home they were liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>.(b) Other assets <strong>in</strong>clude cash <strong>in</strong>vestments, trust funds, the cash-<strong>in</strong> value <strong>of</strong> life <strong>in</strong>surance <strong>and</strong> collectibles.(c) Small adjustments have been made to these three items <strong>in</strong> order for totals to balance. <strong>The</strong> reason for what wouldotherwise be small discrepancies is that the imputations <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> undertaken by the RBA omitted five componentsasked on the Person Questionnaire: bank accounts, superannuation, credit card debt, HECS debt <strong>and</strong> other personaldebt. <strong>The</strong> authors imputed these items but did not constra<strong>in</strong> the imputation to force the total <strong>of</strong> all components toequal the previously imputed total asset <strong>and</strong> total debt values. Our <strong>in</strong>tention is to revise the imputation to address thisproblem.Note: All results are weighted up to population size. <strong>The</strong> national population <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s was 7,540,411.Overall, non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets dwarf f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets. Most <strong>household</strong>s lack liquidity. <strong>The</strong>y have little cash <strong>and</strong>little that they can easily cash up if normal sources <strong>of</strong> market <strong>in</strong>come are temporarily or permanently cut <strong>of</strong>f or ifemergency expenditures are required. This means they must rely primarily on pension <strong>and</strong> benefit entitlements.This is especially clear when one remembers that, until one retires, superannuation is not available <strong>and</strong> so, whileclassified as a f<strong>in</strong>ancial asset, it is not liquid. Some could perhaps obta<strong>in</strong> loans <strong>in</strong> an emergency, although, asnoted above, it is difficult for low-<strong>in</strong>come <strong>household</strong>s to obta<strong>in</strong> credit at reasonable <strong>in</strong>terest rates.12 Social Policy Research Paper No. 33

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsIssue 2:Has the level <strong>and</strong> composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> changed <strong>in</strong> recent years? If so, towhat extent have <strong>in</strong>creases been due to possibly transient <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> hous<strong>in</strong>g values?To date, the HILDA survey has only asked about <strong>wealth</strong> once—<strong>in</strong> 2002. So from HILDA we cannot directly answerquestions about trends <strong>in</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>. However, all published estimates, both from the <strong>Australia</strong>n Government(ABS, cat. nos 5232.0 & 5204.0) <strong>and</strong> from academic sources (Kelly 2001, 2003) show total <strong>household</strong> assets <strong>and</strong>net worth <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g faster than the rate <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>flation <strong>in</strong> recent years. For most <strong>of</strong> the 1990s, stock market <strong>and</strong>property prices grew strongly. However, stock market values grew more rapidly than property prices. <strong>The</strong>n <strong>in</strong> theperiod 2000 to 2003, world stock market values fell sharply, although the <strong>Australia</strong>n market fell much less, <strong>and</strong>property prices rose rapidly <strong>in</strong> all capital cities. So <strong>in</strong> this latter period the rise <strong>in</strong> non-f<strong>in</strong>ancial asset values farexceeded the rise <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets (which barely kept up with <strong>in</strong>flation).Another key po<strong>in</strong>t is that <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>household</strong>s are chang<strong>in</strong>g their asset portfolios. Property still dom<strong>in</strong>ates,but f<strong>in</strong>ancial assets <strong>in</strong> the form <strong>of</strong> shares <strong>and</strong> superannuation are becom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly significant (Kelly 2001,2003). (Trends <strong>in</strong> superannuation are discussed <strong>in</strong> some detail under Issue 4.1.)<strong>The</strong> question as to whether recent <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> are likely to prove transient because they aredue to hous<strong>in</strong>g price <strong>in</strong>creases is thus hard to answer. On the one h<strong>and</strong>, it may well be that <strong>in</strong> most future yearseither the stock market or the hous<strong>in</strong>g market will do well <strong>and</strong> that most <strong>household</strong>s will be positioned to ga<strong>in</strong>some advantage from either development. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, it rema<strong>in</strong>s true that most <strong>household</strong>s still st<strong>and</strong> toprosper more from hous<strong>in</strong>g market ga<strong>in</strong>s than stock market ga<strong>in</strong>s.3.3 <strong>The</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>Issue 3a: What is the overall <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>?In <strong>Australia</strong>, as <strong>in</strong> other Western countries, <strong>wealth</strong> is much more unequally distributed than <strong>in</strong>come (Atk<strong>in</strong>son,Ra<strong>in</strong>water & Smeed<strong>in</strong>g 1995). <strong>The</strong> most commonly used measure <strong>of</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> is the G<strong>in</strong>i coefficient whichranges between 1 (all <strong>wealth</strong> is held by one <strong>household</strong>) <strong>and</strong> 0 (every <strong>household</strong> has the same <strong>wealth</strong>). In 2002the G<strong>in</strong>i coefficient <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> net worth was 0.624. This can be compared with a G<strong>in</strong>i coefficient <strong>of</strong> 0.422 for<strong>household</strong> gross <strong>in</strong>comes <strong>and</strong> 0.382 for <strong>household</strong> disposable <strong>in</strong>comes (see Table 3).It should be noted that only moderate correlations are found between <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>come. In HILDA, thecorrelation <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> net worth with <strong>household</strong> gross <strong>in</strong>come was 0.35, <strong>and</strong> with net <strong>in</strong>come it was0.34. 6 Such correlations may seem surpris<strong>in</strong>gly low, but similar results are found <strong>in</strong> other Western countries(Klevmarken, Lupton & Stafford 2003). If analysis is restricted to <strong>household</strong>s headed by prime‐age men <strong>and</strong>women (aged 25 to 55), the correlations are somewhat higher at 0.40 for gross <strong>in</strong>come <strong>and</strong> 0.39 for net <strong>in</strong>come.<strong>The</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs that <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>come are not highly correlated <strong>and</strong> that <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong>equality is greater than <strong>in</strong>come<strong>in</strong>equality are both primarily due to the greater dependence <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> on age, or rather on sav<strong>in</strong>g as one ages.Wealth also depends somewhat on <strong>in</strong>heritance although, contrary to widespread impressions, most <strong>wealth</strong>ypeople are ‘self-made’ rather than be<strong>in</strong>g beneficiaries <strong>of</strong> large <strong>in</strong>heritances—see, for example, the list <strong>of</strong><strong>Australia</strong>’s 200 <strong>wealth</strong>iest people (Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Review Weekly 2004). So <strong>wealth</strong> accumulates primarily throughboth voluntary sav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> compulsory superannuation, <strong>and</strong> these sav<strong>in</strong>gs compound as people age. 7 Incomealso <strong>in</strong>creases with age but the gradient is not as steep as <strong>wealth</strong>’s compound<strong>in</strong>g gradient.Table 3 presents summary data on the <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> assets, debts, net worth <strong>and</strong> their ma<strong>in</strong> components. Also<strong>in</strong>cluded for comparison are measures <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>come <strong>distribution</strong>.13

<strong>The</strong> <strong>structure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>Table 3:<strong>The</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>come, G<strong>in</strong>i coefficientsAssets/debts/<strong>in</strong>comeTotal assetsTotal debtsNet worthGross <strong>in</strong>comeNet <strong>in</strong>comeSpecific types <strong>of</strong> assets/debtsProperty assetsSuperannuationVehiclesBank accountsProperty debtG<strong>in</strong>i0.5900.7570.6240.4220.382G<strong>in</strong>i0.5880.7510.5630.7720.791Table 3 gives G<strong>in</strong>i coefficients for the types <strong>of</strong> assets <strong>and</strong> debts held by most <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>household</strong>s. It can beseen that, relatively speak<strong>in</strong>g, hous<strong>in</strong>g assets <strong>and</strong> vehicle values are somewhat less unequally distributed thantotal assets, while superannuation <strong>and</strong> bank sav<strong>in</strong>gs are more unequally distributed. Debts show even greaterdispersion than assets—the G<strong>in</strong>i <strong>of</strong> total <strong>household</strong> liabilities be<strong>in</strong>g 0.757, with the G<strong>in</strong>i for property debt at0.791. In expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g these differences, a key po<strong>in</strong>t is that assets <strong>and</strong> debts are positively correlated (r=0.45).<strong>The</strong> reason for this <strong>in</strong>itially surpris<strong>in</strong>g correlation is that the more you own, the more you can borrow. Well-<strong>of</strong>f<strong>household</strong>s can readily obta<strong>in</strong> loans at reasonable rates <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest, whereas poor <strong>household</strong>s cannot. A similarpo<strong>in</strong>t applies to sav<strong>in</strong>gs. Households with high <strong>in</strong>comes f<strong>in</strong>d it much easier to save, <strong>and</strong> once a reasonable level<strong>of</strong> assets has accumulated, they are more likely to seek higher risk–return ratios <strong>and</strong> will therefore, <strong>in</strong> general,tend to accumulate sav<strong>in</strong>gs more rapidly than less well-<strong>of</strong>f <strong>household</strong>s. Hence the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Table 3 that banksav<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> superannuation sav<strong>in</strong>gs are highly concentrated.<strong>The</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> among older <strong>household</strong>s (reference person aged 65 <strong>and</strong> over) is a little less unequalthan it is <strong>in</strong> the total population. <strong>The</strong> G<strong>in</strong>i <strong>of</strong> net worth for this group is 0.563 <strong>and</strong> for assets it is 0.560.Another method <strong>of</strong> summaris<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> is to show the shares owned by various quantiles.Table 4 gives the shares <strong>of</strong> total net worth owned by each decile <strong>and</strong> by the <strong>wealth</strong>iest 5 per cent.Table 4:Shares <strong>of</strong> total <strong>wealth</strong> (net worth) by decilesn=7,245 <strong>household</strong>s Share (%) Median ($’000)Wealthiest decile 44.9 1,394.3(<strong>wealth</strong>iest 5%) (31.0) (2,511.8)9th decile 18.2 727.28th decile 12.4 498.97th decile 9.0 364.76th decile 6.5 262.15th decile 4.5 181.84th decile 2.8 113.63rd decile 1.3 54.52nd decile 0.4 14.0Least <strong>wealth</strong>y decile negative 014 Social Policy Research Paper No. 33

f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs<strong>The</strong> HILDA data <strong>in</strong>dicate that, <strong>in</strong> 2002, the <strong>wealth</strong>iest decile owned 44.9 per cent <strong>of</strong> total <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>(median hold<strong>in</strong>gs=$1,394,400) <strong>and</strong> the <strong>wealth</strong>iest 5 per cent owned 31.0 per cent (median=$2,511,800). Forreasons outl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Section 2, it is likely that we somewhat underestimated the assets <strong>and</strong> national share <strong>of</strong> therichest <strong>household</strong>s.Surpris<strong>in</strong>gly, then, our estimates for the ‘top end <strong>of</strong> town’ are <strong>in</strong> fact a little higher than recent imputed estimatesderived ma<strong>in</strong>ly from ABS national aggregate measures. Kelly (2001) estimated that the top 5 per cent held30 per cent <strong>of</strong> net worth <strong>in</strong> 1998 <strong>and</strong> Northwood, Rawnsley <strong>and</strong> Chen (2002) estimated that, <strong>in</strong> 2000, the topdecile held 43 per cent, with the top qu<strong>in</strong>tile hold<strong>in</strong>g 61 per cent. If it is true that the share <strong>of</strong> the top end has<strong>in</strong>creased <strong>in</strong> the few years s<strong>in</strong>ce these imputed estimates were made, it is likely to be due to rapid house price<strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> all the ma<strong>in</strong> capital cities.HILDA <strong>in</strong>dicates that, by 2002, 8.8 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s had a net worth over $1 million, with 11.2 per centhold<strong>in</strong>g assets over the million dollars mark. So, <strong>in</strong> a sense, about 1.8 million people liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 638,000 <strong>Australia</strong>n<strong>household</strong>s could be described as millionaires.At the lower end <strong>of</strong> the <strong>distribution</strong>, the poorest decile <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s on average have debts exceed<strong>in</strong>g theirassets (negative net worth), with median net worth be<strong>in</strong>g just $24. In all, the least <strong>wealth</strong>y half <strong>of</strong> the populationowns only 9 per cent <strong>of</strong> total <strong>household</strong> net worth.Issue 3b: How are <strong>wealth</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>debtedness distributed among age cohorts? How wide is the gapbetween the most <strong>and</strong> least <strong>wealth</strong>y cohorts? How is <strong>wealth</strong> distributed with<strong>in</strong> cohorts?In this sub-section we review cohort differences <strong>in</strong> <strong>household</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>. As is already clear, <strong>wealth</strong> is heavilyaffected by age. From a public policy st<strong>and</strong>po<strong>in</strong>t the key issue is whether cohorts approach<strong>in</strong>g retirement <strong>and</strong>those recently retired have adequate assets to enjoy a reasonable lifestyle after they f<strong>in</strong>ish paid work.In Table 5 <strong>and</strong> subsequent tables, ‘couple <strong>household</strong>s’ are classified by the age <strong>of</strong> the male partner. 8 Inlone‐parent <strong>household</strong>s the ‘reference person’ is the lone parent <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle person <strong>household</strong>s it is thatperson. 9 Similarly to many <strong>Australia</strong>n Government publications, we have divided <strong>household</strong>s <strong>in</strong>to those withreference persons <strong>in</strong> the 15 to 24 years cohort, then 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54 <strong>and</strong> so on.Table 5 gives an overview <strong>of</strong> the differences between <strong>and</strong> with<strong>in</strong> cohorts by focus<strong>in</strong>g just on net worth. It showsthe mean (average) net worth <strong>of</strong> each cohort <strong>and</strong> then the net worth at the midpo<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> each qu<strong>in</strong>tile—that is, atthe 10 th , 30 th , median, 70 th <strong>and</strong> 90 th percentiles <strong>of</strong> the <strong>distribution</strong>.Table 5:Age cohorts, net worth <strong>of</strong> <strong>household</strong>s at the cohort mean <strong>and</strong> at the 10th, 30th, median, 70th <strong>and</strong>90th percentilesHouseholdreferenceperson’s ageMean($’000)10thpercentile($’000)30thpercentile($’000)Net worthMedian($’000)70thpercentile($’000)90thpercentile($’000)15–24 28.3 –8.5 0.2 5.0 17.0 89.025–34 162.6 0.8 24.3 74.6 159.7 385.035–44 340.9 7.0 83.9 204.8 381.0 727.745–54 521.3 29.5 183.5 361.7 580.0 1,130.155–64 671.8 17.1 216.0 422.1 741.5 1,508.865–74 530.3 19.9 181.0 318.0 538.0 1,127.075+ 348.8 15.3 138.0 244.5 361.3 768.0All 404.8 4.2 83.0 218.6 428.0 934.2Two contrast<strong>in</strong>g results show through clearly <strong>in</strong> this table. <strong>The</strong> first is the strong dependence <strong>of</strong> <strong>wealth</strong> onage or, really, time spent sav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>vest<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> second which, while not contradictory, po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> a differentdirection—that is, even with<strong>in</strong> age cohorts there are great disparities <strong>in</strong> <strong>wealth</strong>.15