Dental Press International

Dental Press International

Dental Press International

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ISSN 2176-9451Volume 16, Number 3, May / June 2011<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> <strong>International</strong>

v. 16, no. 3 May/June 2011<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod. 2011 May-June;16(3):1-164ISSN 2176-9451

[abor abormgtwitter.com/abormgth8 CONGRESS OF THE BRAZILIAN ASSOCIATIONOF ORTHODONTICS AND DENTOFACIAL ORTHOPEDICSth12-15 october, 2011, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil6parallel events of ALADO, BBO, GRUPO, ENAP, ABOL e CFO.15 courses with the highlights of national and international speakers.50 hours of activities to broaden your knowledge.152 lectures forming a diversified scientific grid.10002m of trade show full of attractions.And a city fullof warmthand entertainmentto welcome you!<strong>International</strong> Speakers confirmedMcNamara Course Freefor members registered before June 30, 2011 ABOR.Take advantage of special conditions related to ABOR.James McNamaraUSAAlbino TriacaGermanyEustáquio AraújoUSAGiuseppe ScuzzoItalyLeena PalomoUSAMarco RosaItalyMartim PalomoUSARolf BehrentsUSAStephen YenUSA[Register now!Special conditions related to ABOR.Submit your Scientific Paper:FREE THEME, POSTERS, or CASE STUDY.Achievement Sponsorship Organization Agency OfficialSupport

Ertty

Uma programação científica voltadapara Uma a prática programação avançada científica da Ortodontia voltadae da para Ortopedia a prática Funcional avançada da dos Ortodontia Maxilares.e da Ortopedia Funcional dos Maxilares.A scientific agenda focused on the advancedpractice A scientific of Orthodontics agenda focused and on the the Functional advancedpractice Orthopedics of Orthodontics of the and Maxillaries. the FunctionalOrthopedics of the Maxillaries.15 a 17 de setembro • 2011 • Anhembi • São PauloSeptember 15 a 17 15 de thru setembro 17, Anhembi • 2011 Convention • Anhembi Center, • Sao São Paulo, PauloBrazilSeptember 15 thru 17, Anhembi Convention Center, Sao Paulo, BrazilMódulo/module 1: Finalização ortodôntica: estética e oclusão / Orthodontic completion: esthetics and occlusionMinistradores/lecturers: Módulo/module 1: Finalização Ana Carla Nahás; ortodôntica: Flávio estética Vellini e Ferreira; oclusão Weber / Orthodontic Ursi; Flavio completion: Cotrim-Ferreira esthetics and occlusionMinistradores/lecturers: Ana Carla Nahás; Flávio Vellini Ferreira; Weber Ursi; Flavio Cotrim-FerreiraMódulo/module 2: Tratamento ortodôntico de más-oclusões assimétricas / Orthodontic treatment of bad asymmetric occlusionsMinistradores/lecturers:Módulo/module 2: TratamentoArno Locks;ortodônticoMarcos Janson;de más-oclusõesMaurício Sakima;assimétricasGuilherme/ OrthodonticJansontreatment of bad asymmetric occlusionsMinistradores/lecturers: Arno Locks; Marcos Janson; Maurício Sakima; Guilherme JansonMódulo/module 3: O estado da arte na Ortodontia – filosofia de tratamento ortodôntico MBT – uma Ortodontia ao alcance de todos /Módulo/module 3: O estado da arte na Ortodontia – filosofia de tratamento ortodôntico MBT – uma Ortodontia ao alcance de todos /The state-of-the-artThe state-of-the-artin Orthodonticsin Orthodontics– philosophy– philosophyofofthetheMBTMBTorthodonticorthodontic treatmenttreatment––OrthodonticsOrthodonticsthatthateveryoneeveryonecancanaffordaffordMinistradores/lecturers: Ministradores/lecturers: Ricardo Ricardo Moresca; Moresca; Reginaldo Reginaldo Zanelato Zanelato Trevisi; Trevisi; Cristina Cristina Domingues; Domingues; Hugo Hugo Trevisi TrevisiMódulo/module Módulo/module 4: Disgenesias: 4: visão visão contemporânea do do diagnóstico; bases biológicas para para compreensão, orientação orientação e tratamento e tratamento / /Dysgenesis, Dysgenesis, contemporary vision vision of the of the diagnosis; biological bases for understanding, guidance and and treatmentMinistradores/lecturers: Alberto Consolaro; Daniela Garib; Maurício Cardoso; Leopoldino Capelozza Filho Filho700 places320 already completed700 places320 already completedUm encontro para quem Mais. Participe. Virada de preço em 3/6.Um encontro para quem é Mais. Participe. Virada de preço em 3/6.A meeting for someone who is More. Participate. Enrollment fee will change on June 3 rd .A meeting for someone who is More. Participate. Enrollment fee will change on June 3 rd .Programação científica completa e adesões on-line / Complete scientific agenda and on-line enrollmentsProgramação científica completa e www.ortociencia.com.br/ortonewsadesões on-line / Complete scientific agenda and on-line enrollmentsPromoçãoPromotionPromoçãoPromotionRealizaçãoRealizationRealizaçãoRealizationwww.ortociencia.com.br/ortonewsInformações adicionais e adesões / Additional information and enrollmentsInformações 55 11 adicionais 2168-3400 e (Camila adesões Adrieli) / Additional – ortonews@ortociencia.com.brinformation and enrollmentsApoio 55 11 2168-3400 (Camila Adrieli) – ortonews@ortociencia.com.brInstitutional SupportApoioInstitutional Support

James McNamaraEstados UnidosAlbino TriacaAlemanhaEustáquio AraújoEstados UnidosGiuseppe ScuzzoItáliaLeena PalomoEstados UnidosMarco RosaItáliaMartim PalomoEstados UnidosRolf BehrentsEstados UnidosStephen YenEstados UnidosE v e n t s C a l e n d a r2º Congresso Internacional MBTDate: August 25, 26 and 27, 2011Location: Abzil - São José do Rio Preto /SP, BrazilInformation: (55 18) 3222-4285cursos@trevisi.com.br15º Encontro AOA - “De Volta Para o Seu Futuro”Date: August 26 and 27, 2011Location: Hotel Fazenda Salto Grande - Araraquara / SP, BrazilInformation: (55 16) 3397-4924gestos@gestos.com.br2º CIOMT – Congresso Internacional de Odontologia de Mato GrossoDate: September 15, 16 and 17, 2011Location: Hotel Fazenda Mato Grosso - Cuiabá / MT, BrazilInformation: (55 65) 3321-4428 / 3624-5212www.ipeodonto.com.brabor abormgtwitter.com/abormg8º Congresso da Associação Brasileira de Ortodontia e Ortopedia FacialDate: October 12 to 15, 2011Location: Belo Horizonte / MG, BrazilInformation: www.congressoabor2011.com.br/10 | 11 | 12 | NOV | 2011 | CENTRO DE CONGRESSOS DE LISBOA | PORTUGALCongresso Internacional de Ortodontia, Implantodontia e Cirurgia OrtognáticaDate: November 4 and 5, 2011Location: Vale do Paraíba / SP, BrazilInformation: (55 11) 4368-5678[Inscreva seu Trabalho Científico:Realização Patrocínio Organização Agência OficialApoio[XX Congresso OMD (Ordem dos Médicos Dentistas)Date: November 10, 11 and 12, 2011Location: Centro de Congressos de Lisboa - PortugalInformation: www.omd.pt/congressoGOLD SPONSORSCONFERENCISTA CONVIDADOJORGE FABER | BRORTODONTIAPATROCINADORES OFICIAIS1º Congresso Internacional FASURGS - Cirurgia Bucomaxilofacial,Implantodontia e OrtodontiaDate: November 12, 13 and 14, 2011Location: FASURGS - Passo Fundo / RS, BrazilInformation: (55 54) 3312-4121www.fasurgs.edu.br/congresso<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 19 2011 May-June;16(3):19

News7 th Meeting Abzil/3M of Individualized OrthodonticsIt was held in Belém (PA, Brazil),between 26 and 28 of May, the 7 th Meeting of Individualized Orthodontics,with the presence of the speakers: Leopoldino Capelozza Filho, Laurindo Furquim, Jesus M. Pinheiro Jr.,Sílvia Braga Reis, Sérgio Luiz de Azevedo Silva, José Valladares Neto and David Normando. Prof. Capelozzapresented the book “Metas Terapêuticas Individualizadas (Individualized Therapeutic Goals)”, his secondpublication by the <strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> Publishing Co.Drs. Diana A. Athayde Fernandes and Dr. LeopoldinoCapelozza.Drs. Thiene Normando and Sílvia Reis.Event organizers and professors.Drs. Mielli Teixeira e Silva and Mara Sandra FerraisTobias.Drs. Eduardo Maranhão, Eurico Correia, JesusMaués P. Junior and Theodorico Neto.Drs. Adriana V. M. da Silva and Edilson da Silva.Drs. Hellen G. A. Santos and Lucyana Azevedo. Drs. Roberta F. Marbá and Renata B. Neri. Drs. Carolina Lima and Leopoldino Capelozza.Drs. Marília Guimarães and Fernanda Pinheiro. Drs. Murilo Neves and Rafael Simas. Drs. Iara Reis, Yuri Sasai, Laurindo Furquim andSocene Veloso.<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 21 2011 May-June;16(3):20-1

W h a t ´ s n e w i n D e n t i s t r yCephalometry is an important predictor ofsleep-related breathing disorders in childrenJorge Faber*, Flávia Velasque**Sleep-related breathing disorders (SBD) havebeen studied and treated for a long time in adults,but little attention has been given to children, forwhom SBD may be as serious as for adults. Parents,guardians and healthcare personnel should payclose attention to these problems, which may betreated during childhood. Their effects on everydaylife, such as hyperactivity and poor school achievement,may have a severe impact on the developmentof an individual and may clearly affect health.The relevance of this problem has motivated authorsto evaluate the cephalometric characteristicsof children with SBD. 1 Cephalometry is an importantfacial morphometry tool available practicallyall over the world. This study sample included 70children (34 boys; mean age = 7.3±1.72 years) whousually snored and had symptoms of sleep-relatedobstructive breathing disorders for over 6 months.Nocturnal polysomnography was used to dividechildren into 3 groups: 26 children with a diagnosisof obstructive sleep apnea (OSA); 17 with signs ofupper airway resistance syndrome (UARS), and 27snorers. The control group had 70 children with nobreathing obstructions paired for age and sex. Lateralhead radiographs were obtained, and cephalogramswere traced and measured.Children with SBD had a shorter mandible (P= 0.001) and a greater inclination in relation to thepalatal plane (P = 0.01). Anterior face height (P =0.01) and lower face height (P = 0.05) were greaterthan in control children. Their soft palate was longer(P = 0.018) and thicker (P = 0.002). Airwayshad a smaller diameter in the nasopharyngeal region,but the oropharynx had a greater diameter atthe base of the tongue (P = 0.01). The hyoid bonewas placed at a more inferior position (P < 0.01),and craniospinal angles were greater than thosefound in the control group, in which children hadno breathing obstruction.When divided in subgroups according to diseaseseverity, children with OSA had significantdifferences from children in the control group, particularlyfor the oropharyngeal variables. Childrenwith UARS and snoring also had differences fromthe control groups, but subgroups with obstructionwere not reliably distinguished from each otherby cephalometric measures. Logistic regression revealedthat UARS and OSA were associated witha decrease in pharyngeal diameter in the adenoidand uvula tip regions, an increase in its diameter inthe region of the base of the tongue, and a thick softpalate. In addition, their maxilla had a more anteriorposition in relation to the cranial base.This is an important study because it shows thatcephalometry may be an important predictor ofSBD in children. Special attention should be givento the pharyngeal measures. Children with SBDshould undergo systematic orthodontic evaluationsbecause of the effects of OSA on the developmentof craniofacial bones. The orthodontist is the specialistwith the best knowledge of the diagnostictools for these cases and may substantially contributeto improving health and quality of life of childrenwith SBD.* Associate Professor, Orthodontics, Universidade de Brasília, Brazil.** Private practice, Orthodontics and Pediatric Orthodontist.<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 22 2011 May-June;16(3):22-4

Faber J, Velasque FShould teeth be extracted at the beginning ofprosthetic treatment?The usual first option for dentists and laypeoplewhen a tooth has problems is to treat andpreserve it. However, clinical management oftenhas to be less conservative. Therefore, dentistsoften face the difficult task of deciding aboutthe effect and importance of the multiple riskfactors of periodontal, endodontic or prostheticorigin that may affect the prognosis of an abutment.The relevance of this topic and the changesin concepts due to the development of newtechniques in the different dental specialties ledthe authors to conduct a review whose purposewas to summarize the critical factors involvedin decisions about whether a problematic toothshould be treated and preserved or extracted andpossibly replaced with an implant. 2A literature search was conducted for peerreviewed studies published in English and foundin MEDLINE (PubMed) from 1966 to 2009.Different keyword combinations were used,such as treatment plan and decision making,periodontics, endodontics, dental implants orprosthesis. In addition, the reference lists of allrelevant studies and reviews were surveyed.The study concluded that tooth preservationand the acceptance of risks are properly definedfor several situations. At first, the tooth shouldbe preserved if not extensively damaged andwhen it has a strategic value, either esthetic orfunctional. This applies especially for patientswith implant contraindications. Moreover, preservationis further recommended in case thetooth is in an intact arch, and when the preservationof the gingival structures is fundamental.In contrast, when restorations are planned forall the mouth, the strategic use of tooth implantsis recommended. In addition, several smallerfixed prostheses, either implants or abutments,may be used. In this case, teeth whose long-termprognosis is excellent should be selected. Theseprocedures ensure that the risk of failure of allthe restorations will be reduced.<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 23 2011 May-June;16(3):22-4

What’s New in DentistryObesity is associated withperiodontal infectionA common observation made by clinicaldentists is that obese patients seem to havemore frequent periodontal infections than therest of the population. This possible association,relevant because additional care should be providedfor obese people, has been recently analyzedin an adult population. 3The study included 2,784 dentate, non-diabeticindividuals aged 30 to 49 years. Obesity wasassessed according to body mass index (BMI),body fat percentage (BF%) and waist circumference(WC). The extension of periodontal infectionwas assessed using the number of teeth withperiodontal pockets (whose depth was equal toor greater than 4 mm) and was classified intofour categories 0; 1-3; 4-6; 7 or more.The authors found a significant positive associationbetween the number of teeth withdeep periodontal pockets and BMI. The associationwas found among both men and women,and also among those who never smoked. Thenumber of teeth with deep periodontal pocketswas also associated with BF% and WC amongindividuals who never smoked.This study results suggest that periodontalinfection, measured according to the number ofteeth with deep periodontal pockets, seems to beassociated with obesity. However, no causal inferencemay be made, and further studies should elucidatethe role of periodontal infection in obesity.However, findings suggest that the periodontalhealth of obese patients deserves special attention.ReferEncEs1. Pirilä-Parkkinen K, Löppönen H, Nieminen P, Tolonen U, PirttiniemiP. Cephalometric evaluation of children with nocturnal sleepdisorderedbreathing. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32(6):662-71.2. Zitzmann NU, Krastl G, Hecker H, Walter C, Waltimo T, Weiger R.Strategic considerations in treatment planning: deciding when totreat, extract, or replace a questionable tooth. J Prosthet Dent.2010;104(2):80-91.3. Saxlin T, Ylöstalo P, Suominen-Taipale L, Männistö S, Knuuttila M.Association between periodontal infection and obesity: results ofthe Health 2000 Survey. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:236-42.Contact addressJorge FaberE-mail: faber@dentalpress.com.br<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 24 2011 May-June;16(3):22-4

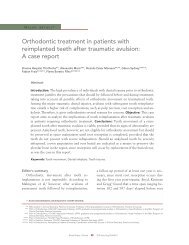

O r t h o d o n t i c I n s i g h tIndirect bone resorption in orthodonticmovement: when does periodontalreorganization begin and how does it occur?Alberto Consolaro*, Lysete Berriel Cardoso**, Angela Mitie Otta Kinoshita***, Leda Aparecida Francischone***,Milton Santamaria Jr****, Ana Carolina Cuzuol Fracalossi*****, Vanessa Bernardini Maldonado******Tooth movement induced by orthodontic appliancesis one of the most frequent therapeuticprocedures in clinical dental practice. The searchfor esthetics and functionality, both oral and dental,demands orthodontic treatments, which areoften associated with root resorptions that may,in extreme cases, lead to tooth loss, periodontaldamage, or both.The knowledge of induced tooth movementbiology, based on tissue, cell and molecularphenomena that take place on each day duringmovement progression, enable us to act safelyand consciously when using drugs, proceduresand interventions to optimize orthodontic treatmentand patient comfort, to reduce or avoidroot resorptions and to treat systemically compromisedpatients.The experimental model of induced toothmovement described by Heller and Nanda 5 hasbeen widely adopted 3,10 because results can be extrapolatedto orthodontic clinical practice (Fig 1).Standardization and detailed descriptions of thisexperimental model ensure greater applicabilityand easier result extrapolations. The improvementof this model may provide further knowledgeabout the biology of induced tooth movement. 3,10In general, experimental times were 5 to 7 daysin the first studies. 7,8,9,13 However, it remains unclearwhat tissue phenomena take place in murinemaxillary first molar roots that received intenseforces and produce indirect bone resorption. Severalquestions raised in previous studies 4,6,10,11 usingthis model have not been answered to this date:» Is the root resorption associated with experimentalinduced tooth movement moreclosely related with frontal or underminingbone resorption?» How long does it take to eliminate the hyalineareas, and when does the periodontalligament begin its reorganization?» When and how is the reabsorbed corticalbone replaced to reinsert the periodontalligament?» Do the hyalinized areas of connective tissueundergo phagocytosis, resorption or circumscription?» Where does root resorption occur, immediatelynext to or away from hyaline areas?» When indirect bone resorption is suspected,do microscopic data suggest the adoption ofa greater interval for the reactivation of theorthodontic appliance?How to cite this article: Consolaro A, Cardoso LB, Kinoshita AMO, Francischone LA, Santamaria Jr M, Fracalossi ACC, Maldonado VB. Indirect bone resorptionin orthodontic movement: when does periodontal reorganization begin and how does it occur? <strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod. 2011 May-June;16(3):25-31.* Head Professor, School of Dentistry of Bauru (FOB) and Graduate Program of School of Dentistry of Ribeirão Preto (FORP), University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil.** Professor, Histology, Anhanguera School, Bauru, Brazil.*** Professor, Oral Biology Program, Sagrado Coração University, Bauru, Brazil.**** Professor, Orthodontics Program, Araras University, Araras, Brazil.***** MSc in Oral Pathology from FOB. PhD from Federal University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.****** MSc in Pediatric Dentistry from FORP-USP.<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 25 2011 May-June;16(3):25-31

Indirect bone resorption in orthodontic movement: when does periodontal reorganization begin and how does it occur?ICM1 st MABFIGURE 1 - Murine skull where molars and incisors (IC) are seen, particularly maxillary first molar (M1 st M) after movement by appliance designed by Hellerand Nanda. 5 Microscopic cross-section (B) shows tooth roots, particularly M1 st M, in cervical plane.<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 26 2011 May-June;16(3):25-31

Consolaro A, Cardoso LB, Kinoshita AMO, Francischone LA, Santamaria Jr M, Fracalossi ACC, Maldonado VBABCDBDLITMLMBFIGURE 2 - In A, murine first molar and its five roots. In the mesiobuccal(MB) root, forces dissipate along its larger and longer structure.In other roots (distobuccal, intermediate, distolingual and mesiolingual),delicate structures clearly show effects of forces onperiodontal tissues. In B, red lines show cross-sections at cervicallevel in schematic drawing of a longitudinal section of murine firstmolar. In C, red lines correspond to longitudinal views in crosssectionof murine maxillary first molar (A: modified from Alatli-Kutet al.1; B and C: of Fracalossi 4 ).» When palatal expansion is used, applianceanchorage in maxillary premolars promoteshyalinization of the periodontal ligamenton the buccal face. Forces dissipate and theprocess ends when the midpalatal sutureis separated. Does indirect bone resorptionbegin long before that? When does it actuallybegin, at 3, 5, 7 or 9 days?Few studies investigated the chronology andsequential events of indirect bone resorptionand the consequent periodontal reorganizationresulting from it. Microscopic analyses of theevents induced by intense forces on teeth thatundergo experimentally induced movement inmurine models contributed to answer some ofthe questions raised, such as in the study conductedby Cardoso, 2 together with Consolaro,Kinoshita, Francischone, Santamaria Jr., Fracalossiand Maldonado. Their most interesting findingswere the late results, when the periodontalligament is reorganized and root resorptions aremore active and intense (Figs 6, 7 and 8).In patients, delayed events and periodontalreorganization occur at each activation time,between 15 and 21 days. At the end of six totwelve years, the resulting sum of the severalorthodontic appliance activation times may bedemonstrated by radiographic and CT imagesof periodontal tissues and tooth roots. Knowingeach activation time and its beginning, middleand end substantially increases our chances ofacting to reduce unwanted consequences.Some of the interventions that orthodonticspecialists may choose, based on results of experimentalstudies, are:1) Defining plans to prevent root resorptionand bone loss.2) Distributing the application of forces ontooth structure to reduce patient pain and discomfort.Ligament hyalinization reduces or blockstooth movement and may also be associatedwith root resorption. Knowledge about tissue,<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 27 2011 May-June;16(3):25-31

Indirect bone resorption in orthodontic movement: when does periodontal reorganization begin and how does it occur?vBvPLCECMCbObvHBCHHDPLDFIGURE 3 - Normal periodontal structures on the mesial face of murineM1 st M distobuccal root, which received intense forces in the experimentalmodel designed by Heller and Nanda. 5 B = alveolar bone; PL = periodontalligament; C = cement; D = dentine; P = tooth pulp; V = vessels; Cb= cementoblasts; Ob = osteoblasts; ECM = extracellular matrix. (HE;10X).PPFIGURE 4 - Incipient indirect bone resorption on mesial face of murineM1 st M distobuccal root after application of intense forces for 3 days.Hyalinized periodontal ligament (H) and initial clastic activity (circle)surround it. B = alveolar bone; PL = periodontal ligament; C = cement;D = dentine; P = tooth pulp. (HE; 10X).MSMSMSMSBHHHPLCDPFIGURE 5 - Indirect bone resorption on mesial face of murine M1 st M distobuccal root after application of intense forces for 5 days. Hyalinized periodontalligament (H) and clastic activity (circle) surround it. B = alveolar bone; PL = periodontal ligament; C = cement; D = dentine; P = tooth pulp; MS = marrowspace. (HE; 10X).<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 28 2011 May-June;16(3):25-31

Consolaro A, Cardoso LB, Kinoshita AMO, Francischone LA, Santamaria Jr M, Fracalossi ACC, Maldonado VBMSMSMSMSHBCHPLDPPLFIGURE 6 - Indirect bone resorption (arrows) on mesial face of murine M1 st M distobuccal root after application ofintense forces for 7 days. Hyalinized periodontal ligament (H) and clastic interaction with hyalinized areas surroundit. Root surface exposure due to root resorption induced by death of cementoblasts; several associated bone remodelingunits (circles). B = alveolar bone; PL = periodontal ligament; C = cement; D = dentine; P = tooth pulp; MS= marrow space. (HE; 10X).MSMSBPLHCHHRRDRRFIGURE 7 - Indirect bone resorption (arrows) on mesial face of murine M1 st M distobuccal root after application of intenseforces for 9 days. Ligament is reorganizing and frontal bone resorption is already visible on periodontal surfaceof cortical plate (circle). Hyaline areas remaining from previously hyalinized periodontal segment (H) are associatedwith clastic activity. Root resorption (RR) is seen in cement and dentine, together with active bone remodeling units.B = alveolar bone; PL = periodontal ligament; C = cement; D = dentine; MS = marrow space. (HE;10X).<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 29 2011 May-June;16(3):25-31

Indirect bone resorption in orthodontic movement: when does periodontal reorganization begin and how does it occur?cell and molecular phenomena involved in inducedtooth movement may provide a basis forclinical procedures.Murine molars have 5 roots, 3,5,12 and the experimentalorthodontic appliance (Fig 1) designedby Heller and Nanda 5 applies intenseforces on four roots: distobuccal, intermediate,distolingual and mesiolingual (Fig 2). In the mesialor mesiobuccal root, the forces applied bythe appliance dissipate along larger and longerroot structures, which affect periodontal tissuessimilarly to the application of slight or moderateforces. Because of these characteristics, in theexperimental model the effects of two types offorces may be analyzed at the same time accordingto their intensity: mild/moderate or intense.The distolingual root, according to the studyby Cardoso, 2 may show morphological changesassociated with indirect buccolingual bone resorptionin cross-sections of the cervical regionof the root and the alveolar bone process, as illustratedin Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8.MSMSMSPLHCBPLDFIGURE 8 - Indirect or undermining bone resorption (arrows) on mesial face of murine M1 st M distobuccal root after application of intense forces for 9 days,and more advanced reorganization than in Figure 7. Periodontal ligament is reorganizing together with remnants of cortical bone. Hyaline areas remainingfrom previously hyalinized periodontal segment (H) are associated with clastic activity. B = alveolar bone; PL = periodontal ligament; C = cement; D = dentine;P = tooth pulp; MS = marrow space. (HE;10X).P<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 30 2011 May-June;16(3):25-31

I n t e r v i e wAn interview withJames A.McNamara Jr.• Degree in Dentistry and Orthodontics, University of California, San Francisco.• PhD in Anatomy from the University of Michigan.• Professor of Thomas M. and Doris Graber Chair, Department of Orthodonticsand Pediatric Dentistry - University of Michigan.• Professor of Cell Biology and Development - University of Michigan.• Research Professor at the Center for Human Growth and Development at theUniversity of Michigan.• Author of the book “Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics.”• Milo Hellman Research Award (AAO - 1973).• Lecturer Sheldon E. Friel (European Society of Orthodontics -1979).• Award Jacob A. Salzmann (AAO - 1994).• Award James E. Brophy (AAO - 2001).• Lecturer Valentine Mershon (AAO - 2002).• Award Albert H. Ketcham (AAO - 2008).• Graduate of the American Board of Orthodontics - ABO.• Fellow of the American College of Dentists.• Former President of Edward H. Angle Society of Orthodontists - Midwest.• Editor of series “Craniofacial Growth Monograph” - published by University of Michigan.• Over 250 published articles.• Wrote, edited or contributed to more than 68 books.• Taught courses and conferences in 37 countries.I met James A. McNamara Jr. in the late 70’s when we both became full members of the Edward H. Angle Society ofOrthodontists - Midwest. Jim is one of the most active members, always looking on to break boundaries with new works.During over 30 years, I saw him being presented with all the existing awards and honors in the field of orthodontics.Knowing his ability and persistence, I’m sure that if in the future other awards are instituted, Jim will be there to, with allmerits, conquer them. It is fortunate to have a family that supports and encourages: his wife Charlene, who accompanieshim on every trip, and Laurie, his daughter and colleague, now a partner in his clinic. In addition to Orthodontics, he ispassionate about golf and photography.My sincere thanks to colleagues Bernardo Quiroga Souki, José Maurício Vieira de Barros, Roberto Mario Amaral LimaFilho, Weber Ursi, and Carlos Alexandre Câmara, who accepted the invitation to prepare questions that facilitated thedevelopment of the script of this interview. I hope that readers will experience the same pleasure and satisfaction I felt,when reading the answers. Jim was able to show growth and maturity of his clinical career, based on scientific evidence,with a clarity and simplicity that makes him, besides clinician and researcher emeritus, one of the best speakers of our time.I thank the <strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> for the opportunity to conduct this interview and wish you all a good reading.Carlos Jorge Vogel<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 32 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

McNamara JA Jr1) May I begin by asking you to tell us aboutyour general educational background andyour education in orthodontics?I began my collegiate education at the Universityof California Berkeley, where I majoredin Speech (today called Forensics), not scienceor biology. I then attended the School of Dentistryat the University of California San Francisco,where I received my dental degree and myspecialty education in orthodontics. In 1968, Itraveled 2000 miles east to Ann Arbor and beganmy doctoral studies in the Department of Anatomyat the University of Michigan. I also becameaffiliated with the Center for Human Growthand Development, an interdisciplinary researchunit on the Ann Arbor campus that was headedby Dr. Robert Moyers. I had many wonderfulmentors during my PhD years, including bonebiologist Donald Enlow as well as orthodontistsFrans van der Linden from the Netherlands, KaleviKoski from Finland, Takayuki Kuroda fromJapan and José Carlos Elgoyhen from Argentina.It was an exciting time for a young man like meto conduct research at the University of Michigan.My dissertation concerned the adaptationof the temporomandibular joints in rhesus monkeys,a study completed in 1972. 1,2 I then wasappointed to the University of Michigan faculty.I have been at Michigan ever since.In addition to my current appointments inthe School of Dentistry, the School of Medicine,and the Center for Human Growth and Development,I have maintained a part-time privatepractice in Ann Arbor, now sharing the practicewith my daughter and partner Laurie McNamaraMcClatchey. Given my 40 years experience inprivate practice (with my partners and I sharingthe same patients) as well as through my clinicalsupervision at the University of Michigan(and for eight years at the University of DetroitMercy), I estimate that I have participated in thetreatment of over 9,000 orthodontic patients.Thus, I have both academic and clinical perspectivesconcerning orthodontics and dentofacialorthopedics. Maintaining a private practicewhile being on the Michigan faculty has hadmany advantages.In addition, our research group, which includesTiziano Baccetti and Lorenzo Franchifrom the University of Florence, has addressedmany orthodontic conditions from a clinical perspective,providing data on treatment outcomes.In this interview, I will be referring primarily toclinical investigations conducted by our groupbecause the protocols used in our research effortsare consistent across studies.2) You have been in private practice for along time and have been an innovator ofmany orthodontic and dentofacial orthopedicstreatments. How has your practiceevolved over the years?If anything, my practice philosophy has becomesimpler as the years have passed. I was welleducated at UCSF in fixed appliance treatmentand even used some preadjusted appliances duringmy residency in the mid 1960s. Beginning inthe early 1970s, I began working with a varietyof appliances aimed at modifying craniofacialgrowth, including functional jaw orthopedics(FJO), rapid maxillary expansion (RME) andfacial mask therapy.In 1980, I began formulating and testingprotocols in the early mixed dentition for thecorrection of crossbites and of tooth-size/archsizediscrepancies, first with a bonded expanderand later adding a removable lower Schwarzexpansion appliance. As time passed, I beganto realize how important it is for the orthodontistto have patience during treatment, lettingnormal growth and development of the patienttake place after early intervention (for example,we will talk about creating an environment allowing“spontaneous improvement” in Class IImalocclusion later in this discussion).Today our treatment protocols are far less<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 33 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

Interviewcomplex that they were 20 years ago. Our regimensare clearly defined and standardized forthe most part, 3 as they had to become when Ibegan sharing patient treatment with partnersin my practice beginning in 1989. We also haveplaced significant emphasis on using those protocolsthat are not dependant on required highlevels of patient compliance.3) You thus have been an advocate of earlyorthodontic and orthopedic treatment formuch of your professional career. Today,what are the most important issues relatedto early treatment?In my opinion, perhaps the critical issuetoday is treatment timing. 3 With the recentemphasis on “evidence-based” therapies in bothmedicine and dentistry, we now are gainingan appreciation concerning the nature of thetreatment effects produced by specific protocolsin patients of varying maturational levels.We are moving toward a better understandingconcerning the optimal timing of orthodonticand orthopedic intervention, depending on theclinical condition.In recent years, there has been considerablediscussion among clinicians and researchers alikeconcerning the appropriate timing of interventionin patients who have Class II malocclusions,as has been evidenced by the ongoing discussionsconcerning the randomized clinical trials ofClass II patients funded by the US National Institutesof Health (e.g., North Carolina, Florida).But the issue of “early treatment” is far broaderthan simply arguing about whether a Class IIpatient is better treated in one or two phases.A variety of other malocclusions also mustbe considered within this topic, including themanagement of individuals with Class III malocclusions,those with open and deep bites, and themany patients with discrepancies between thesize of the teeth and size of the bony bases (thelatter comprise about 60% of the patients in ourprivate practice in Ann Arbor). The managementof digital habits also falls within this discussion.4) What are your views about the extentto which a clinician can alter the growth ofthe face?In general, the easiest way for a clinicianto alter the growth of the face is in the transversedimension, orthopedically in the maxilla,orthodontically in the mandible. 4 Rapid maxillaryexpansion (Fig 1) has been shown to be anextremely efficient and effective way of wideningthe maxillary bony base. In the lower arch,however, there is no mid-mandibular suture—soit is virtually impossible to produce orthopedicchange in the mandible other than in combinationwith surgical distraction osteogenesisat the midline. The changes in the lower archessentially are dentoalveolar in nature, such asthose resulting from the use of a removablelower Schwarz appliance (Fig 2).5) How about the correction of Class II andClass III problems?As far as sagittal change is concerned, I thinkthere is a substantial amount of experimental 5,6and clinical evidence 7-10 that mandibular lengthcan be increased over the short-term in comparisonto untreated Class II controls, using a varietyof functional orthopedic appliances. It should benoted, however, that not all investigators havecome to this conclusion. The long-term effectof bringing the mandible forward functionallyis much more uncertain at this time; mostrecent research has shown that the long-termmandibular skeletal effect may be limited to 1-2mm over what would have occurred withouttreatment. 11,12The best data that I have seen that considersthe question of how much mandibular growthcan be influenced over the long term has beenderived from our recent study of Class II patientstreated with the Fränkel appliance. In this<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 34 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

McNamara JA JrFIGURE 1 - The bonded acrylic splint type of rapid maxillary expander thatis used primarily in patients in the mixed dentition is representative of theorthopedic expansion appliances used during treatment. The acrylic portionof the appliance is made from 3 mm thick splint Biocryl. 3FIGURE 2 - The removable lower Schwarz appliance 3 can be usedprior to RME to upright the lower posterior teeth and gain a modestincrease in arch perimeter anteriorly. It produces orthodontic tippingof the teeth only.investigation by Freeman and co-workers, 13 weevaluated patients treated with the FR-2 applianceby Rolf Fränkel of the former GermanDemocratic Republic. Based on my experiencewith a variety of FJO appliances, I considerthe function regulator (FR-2) the best of thefunctional appliances in that it addresses neuromuscularproblems directly as well as skeletaland dental problems. A sample of 30 FR-2patients was compared to a matched group ofuntreated Class II patients. Over the long-term,the increase in mandibular growth in the treatedsample was 3 mm in comparison to controls.6) If mandibular growth can be increasedin length only by 1-2 mm with functionaljaw orthopedics under most circumstances,why use it?Hans Pancherz answered that question eloquentlyduring a seminar at the University ofMichigan when asked the same questions byour residents. 14 He stated simply that “you getthe growth when you need it.” Most studiesof the Herbst appliance have shown that thetreatment effect produced by this tooth-bornetype of FJO appliance is 50% dental and 50%skeletal. 8,15 In comparison to untreated Class IIcontrols, Herbst treatment produces about 2.5to 3.0 mm increased mandibular length duringthe first phase of treatment; our investigationof Twin Block therapy has shown even largershort-term gains in mandibular length. 9,16Normally Herbst or Twin Block wear resultsin the Class II patient having a Class I or super-Class I molar and canine relationship at theend of the first phase of treatment. Full fixedappliances then are used to align and detail thedentition. If the overall treatment outcomeis evaluated, some of the gains in mandibularlength observed during Phase I treatment maydisappear by the end of fixed appliance therapy.11,12 Thus, FJO helps the clinician correct theunderlying Class II malocclusion in a relativelyshort (9-12 months) and predictable manner.Some Class II patients with particularly favourablecraniofacial features before treatment (arelatively closed gonial angle, for instance) maypresent an appreciable improvement in their<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 35 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

Interviewfacial profile due to mandibular advancementfollowing FJO. If a substantial change in theposition of the chin is the primary focus of thetreatment protocol, however, then correctivejaw surgery might be indicated, be it a mandibularadvancement or a simple advancementby genioplasty.Attempting to restrict the growth of themandible presents a significant clinical challenge,particularly in the management of ClassIII malocclusion. One such appliance is the chincup. I have not had extensive first-hand experiencewith the chin cup clinically, although atany given time we usually have one or two chincup patients in our practice or in the universityclinic, with the chin cup used primarily as along-term retention device following facial masktherapy. The chin cup is indicated in patientswho have mandibular prognathism and in whoman increase in lower anterior facial height is notdesirable. A chin cup is not indicated in a patientwho has maxillary retrusion.There have been many studies, especially inAsian populations such as the Chinese, Koreanand Japanese, that have shown over the shorttermthat there can be a restriction in mandibularprojection in comparison to untreated ClassIII individuals. 17,18 As of now, however, there islittle evidence to support the premise that thegrowth of the mandible can be restricted overthe long term (unless the patient wears the chincup continuously from age 6 to age 18, a levelof compliance that is difficult to attain).7) You said earlier that the midface is responsiveto treatment in the transverse dimension.How responsive is the maxilla tosagittal forces?The growth of the midface seems to beinfluenced more readily by treatment than isthe mandible. In the midface, restriction of theforward movement of the maxilla and maxillarydentition in Class II patients has been welldocumentedfor over 60 years, beginning withthe work of Silas Kloehn, 19 among others. Givengood cooperation in a growing patient, thereis no question that extraoral traction is effectivein changing the occlusal relationship fromClass II toward Class I. However our researchon the components of Class II malocclusion hasshown that true maxillary skeletal protrusion isrelatively rare in a Caucasian population. 20,21 Inaddition, good patient compliance is an essentialcomponent of this type of treatment.Regarding protraction of the maxilla with anorthopedic facial mask (Fig 3) in Class III patients,most clinical studies have shown that theamount of true maxillary skeletal protractionis only 1-2 mm over what would occur duringgrowth in untreated Class III subjects. 22,23 ClassIII correction still can occur as a consequenceof facial mask wear due mainly to mandibularmodifications, especially because of favorablechanges in the direction of condylar growth,also in relation to appropriate early treatmenttiming. Increased forward protraction amountsmay be produced if the facial mask is attachedto dental implants or if microimplants or boneanchors are used for skeletal anchorage. 24-268) What changes can be produced in thevertical dimension of the face of a growingpatient?Most orthodontists have found that thevertical dimension is the dimension that is themost difficult to correct therapeutically, andthat observation certainly has been substantiatedby my clinical experience. In a growingpatient, increasing a short lower facial heightis accomplished most effectively with a FJOappliance such as the Twin Block 9,27 or the FR-2of Fränkel, 7 less so with the Herbst appliance.In the long-face patient, controlling thevertical dimension has been particularly challenging.For example, a study by our groupevaluated modification in growth following the<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 36 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

McNamara JA JrFIGURE 3 - The orthopedic facial mask of Petit. 3FIGURE 4 - The vertical-pull chin cup typically is used in combinationwith an acrylic splint expander. 3use of a bonded rapid maxillary expander andvertical-pull chin cup 28 (Fig 4). The effect of thevertical-pull chin cup was evident only in themixed dentition, with little effect noted in thepermanent dentition even though the appliancewas worn at night for 5.5 years on average.9) In Class III cases in the deciduous or earlymixed dentition, what cephalometric parametersdo you use to differentiate amonga true Class III, true developing Class III,and a dentoalveolar Class III malocclusion?I typically do not perform a detailed cephalometricanalysis on a young patient with thosequestions in mind. Our approach to Class IIItreatment primarily is through the use of abonded acrylic splint expander to which havebeen attached hooks for elastics (Fig 5) and anorthopedic facial mask (Fig 3). Typically, thefirst appliance that we use is the bonded expander.29 In many patients (perhaps one-third ofmixed dentition Class III patients), we observea spontaneous improvement of the Class IIIor Class III tendency toward Class I simply byexpanding the maxilla. This favorable changeoccurs almost immediately after maxillary expansion.If further intervention is necessary, thenwe will incorporate an orthopedic facial maskinto the treatment protocol.Any time a patient has a Class III molarrelationship and we use this protocol, first anyCO-CR discrepancy is eliminated just by placingthe facial mask; so we do not try to make thedifferentiation between those three conditionsyou asked about, in that all three conditions aremanaged by the same treatment regimen.10) Do you still use the FR-3 Fränkel appliance?You previously have recommendedthe use of the FR-3, especially in maxillaryretrognathic cases. What are your contemporaryviews on its use?Currently, I actually use more FR-3 appliances30 (Fig 6) than I do FR-2s. Today, the FR-3<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 37 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

InterviewFIGURE 5 - The acrylic splint expander to which have been attachedfacial mask hooks. 3FIGURE 6 - The Fränkel FR-3 appliance. 3 Fränkel 62 states that the distractingforces of the upper lip are removed from the maxilla by theupper labial pads. The force of the upper lip is transmitted through theappliance to the mandible because of the close fit of the appliance tothat arch.usually serves as a retainer, rather than as aprimary treatment appliance. The FR-3 is anappliance that has vestibular shields and alsoupper labial pads that free the maxilla fromthe forces of the associated musculature. 31 TheFR-3 produced similar treatment effects as doesa facial mask-expander combination, but the effectstake much longer to occur in FR-3 therapy. 3In the patient about whom we are suspiciousof a strong tendency for relapse toward aClass III malocclusion after facial mask therapy,we will use the FR-3 as a retainer to be wornat night and around the house during the day.This approach of using the FR-3 as a retainerafter successful facial mask therapy seems tobe a reasonable way of incorporating this typeof Fränkel appliance into our overall treatmentscheme. We do not use the FR-3 often, but itsuse is essential in patients with difficult ClassIII problems.11) Tell us more about the acrylic splint expanderused in combination with the orthopedicfacial mask. Can you elaborate on theuse of this treatment protocol in dentoalveolarClass III or mandibular prognathismcases?As stated before, we use the same basic protocolregardless of the etiology of the Class IIIproblem. When I first heard Henri Petit (then ofBaylor University in Dallas, Texas) speak aboutfacial mask therapy in 1981, I was somewhatcritical of his presentation because he did notdifferentiate among the various types of ClassIII malocclusions according to their etiology.I soon realized that the facial mask-expandercombination is effective regardless of the underlyingetiology of the Class III problem. I haveused essentially the same protocol for the last30 years, starting with the bonded expander.Typically we will deliver the expander and havethe patient expand the appliance 28 times. Ifwe need more turns, the patient is instructedto do so at the next appointment; then we willdeliver the face mask if the underlying Class IIImalocclusion has not corrected spontaneously.We usually recommend that the timing of facialmask therapy correspond to the eruption ofthe maxillary permanent central incisors. 29 I donot like to start much earlier than that because I<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 38 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

McNamara JA Jrwant to make sure that there is maximum verticaloverlap of the permanent upper and lowercentral incisors at the end of facial mask treatment.The establishment of substantial verticaloverlap of the incisors is critical in maintainingthe corrected Class III malocclusion during thetransition to the permanent dentition.12) Do you use as a rule the maxillary expansionappliance with a facial mask, irrespectiveof the transverse width of themaxilla?We use the bonded expander regardless ofwhether or not expansion is required. If thepatient would benefit from widening of themaxilla, we have them expand the appropriatenumber of times. If there is no need to expand,we still have the patient expand 8-10 times toloosen the circummaxillary sutural system. 29 Weand others have found that by mobilizing thesutures of the midface, we presumably affect thecircummaxillary sutural system and facilitatethe forward movement of the maxilla. 3,3213) In the RME/FM appliance, where do youplace the hooks for elastic attachment? Isit at the deciduous canines or deciduousfirst molars?We typically use hooks that extend abovethe upper first deciduous molars. A downwardand forward pull on the maxilla produced bythe elastics counteracts the reverse autorotationof the maxilla that might occur becauseof the direction of pull on the teeth, resultingin a counterclockwise rotation of maxillarystructures.14) What are the force levels of the elasticsthat you prefer?Three different elastics, the same elastics asoriginally recommended by Petit, 33 are used.The first elastic is 3/8” in length and is rated at8 ounces (e.g., Tiger elastics from Ormco Corp.).These elastic generate about 200 grams of forceagainst the maxillary RME appliance. After aweek or so, we switch to heavier elastics (1/2”,14 oz; Whale) that generate about 350 g of force.The final elastic is 5/16” and is rated at 14 oz(Walrus). These elastics generate about 600 gof force, so that by the time we use the thirdtype of elastics, there is a considerable amountof force generated against the maxillary andmandibular structures.15) Is there any particular method you recommendto remove the bonded expander?The debonding procedure is relativelystraightforward. First, one of my chairside assistantsapplies a topical anesthetic gel abovethe appliance in the region of the first andsecond deciduous molars bilaterally. We let thegel activate for a few minutes, and then I willuse a pair of ETM 349 pliers to remove thebonded expander. The ETM 349 plier actuallyis an anterior bond remover that has a sharpedge on one side and a Teflon cap on the other.The Teflon cap is placed on the occlusal surfaceof the appliance, and the sharp edge is insertedunder the gingival margin of the appliance betweenthe first and second deciduous molars.I then use a single strong pulling motion thattakes about half a second, debonding the leftand then the right side of the appliance in onecontinuous motion. Very little or no discomfortis felt by the patient.Obviously the ease of removal of the applianceis dependent on a number of technicalfactors. One of these factors is making sure thatthe proper material is used for the acrylic. I donot recommend the “salt and pepper” type ofcold cure acrylic application for expander constructionbecause the resulting type of acrylicis too rigid; rather, I strongly recommend theuse of 3 mm thick splint Biocryl (Great LakesOrthodontic Products) applied over the wireframework in a thermal pressure machine such<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 39 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

Interviewas a Biostar. By using the latter material, theexpander is somewhat flexible; it then becomesvery easy to break the seal of the adhesive tothe teeth.I also recommend that the chemical cureadhesive Excel (Reliance Orthodontics) isused for the bonding procedure. This adhesiveis made specifically for the bonding of largeacrylic appliances. In addition, a sealer shouldbe placed on the teeth, and “plastic bracketprimer” should be painted inside the expanderprior to the bonding procedure. This primeractually is methyl methacrylate liquid; it softensthe inside of the expander so that it can acceptthe bonding agent. So when we remove theappliance, all the bonding agent comes out inthe appliance and none remains on the teeth,making clean-up easy.16) Do you favor the use of slow expansionor rapid expansion?I have not had much experience in dealingwith protocols that deliver so-called “slow expansion.”34 By that, I mean having the expanderturned every other day or every third day (asmight be used in some young adult patients). Inour practice, we use a one turn-per-day protocolin growing patients, which is not as rapid as theoriginal protocol of two turns-per-day advocatedby Andrew Haas. 35There are two distinct reasons why I havetaken the one-turn-per-day approach, one practicaland one based on long clinical experience.From a practice management standpoint, havinga patient activate the expander twice per daysimply means that I have to see the patient twiceas frequently. We now have almost all patientsactivate the expander once a day for 28 days,which means that I only need to see the patientevery four weeks, a more practical interval thanonce each week or once every two weeks.The second reason has to do with the speedof expansion. Orthodontists across the UnitedStates often contact me concerning problemsthey are experiencing that are associated withRME. One such problem is “saddle nose deformity,”a condition characterized by a loss ofheight of the nose because of the collapse of thebridge. This clinical problem can occur in youngchildren undergoing rapid maxillary expansion(if the expander is removed immediately theunwanted deformity usually resolves withouttreatment). I have heard of 10 instances of thisdeformity over the years. In each instance, theorthodontist was using a protocol of twice-perdayexpansion, a protocol that I do not recommend.It should be noted, of course, that thisclinical recommendation is based purely onanecdotal information and clinical intuition,not hard science.17) You have advocated expanding themaxilla using RME to alleviate moderatecrowding. What is the basis of this approach?This topic has been of great interest to mefor over 3 decades. I received my orthodonticeducation during a time that the extraction ofpermanent teeth was a common occurrence inorthodontics, with a national extraction rate of40% or greater observed during the 1960s and1970s. 36 Since then, the rate of extraction graduallyhas decreased in the United States today toabout 25% nationally. In our practice we extractabout 12-15% of the time in Caucasian patients;however, the extraction rate is substantiallyhigher in patients of Pacific Rim ancestry.In 2003, our research group published apaper in the Angle Orthodontist 37 that dealtwith an analysis of 112 individuals treatedwith a Haas-type expander (Fig 7) combinedwith fixed appliance therapy in the permanentdentition. We found that by using this treatmentprotocol, in comparison to a control samplefrom the University of Michigan Growth Studyand University of Groningen Growth Study, a<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 40 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

McNamara JA Jrresidual increase of about 6 mm in maxillaryarch perimeter and about 4.5 mm in mandibulararch perimeter was observed at age 21 years,value that are highly significant clinically. Thesedata are the “best” data that I have seen withregard to increasing arch perimeter expansionin adolescent patients over the long term.Subsequently, we have conducted many studiesof patients treated initially in the early mixeddentition, two of which I will highlight: one thatdealt with the bonded expander used alone 38 andone in which a mandibular Schwarz expansionappliance 39 that is intended to decompensate thelower arch and gain a modest amount of archperimeter anteriorly was used prior to expansion.In general, the difference in arch perimeterin these two studies over the long term (patientswere ~20 years of age) was slightly less than 4mm in the maxilla and 2.5-3.7 mm in mandiblein comparison to matched untreated controlgroups. Our investigations have shown thatin a borderline case of crowding (i.e., 3-5 mmmandibular tooth-size/arch-size discrepancy)these early expansion protocols are reasonableapproaches to treatment. On the other hand, ifa patient has 7-10 mm or more of crowding inthe mandible, an extraction approach (serial orotherwise) may be in order.18) Tell me about serial extraction as usedin your private practice? Do you advocateany particular sequence?In our private practice my daughter and Icurrently have about 800 active patients, about10 of whom are going through a protocol involvingserial extraction. We use the size ofthe teeth as a guide to patient who requiresserial extractions as the appropriate treatment.In a serial extraction protocol, extractions areindicated when there is at least 7 mm of archlength deficiency in the mandible; usually thisprotocol is undertaken in patients who have wellbalanced faces. If a patient has a severe man-FIGURE 7 - The Haas-type rapid maxillary expander that has both metaland acrylic components. 3dibular skeletal retrusion or severe mandibularprognathism, it is not a good idea to use a serialextraction approach.Our studies of the subjects in the Universityof Michigan Growth Study have shown that thesize of the maxillary permanent central incisorin males of European ancestry is about 8.9 mmand in females about 8.7 mm, with a standarddeviation of 0.6 mm for both sexes. 40 So, as aguideline, if we have a patient whose centralincisor is 10 mm or greater in mesiodistal diameter,he or she would be a potential candidatefor a serial extraction protocol. Obviously, theclinician has to take into account the size of allthe teeth as well as the size of the bony bases.But generally a serial extraction protocol isperformed in patients who have large tooth size(maxillary incisor ≥10 mm). In some instances,expansion of the maxilla followed by a serialextraction procedure ultimately is the treatmentof choice.Typically we order the extraction of all fourdeciduous canines, followed 6-12 months laterby all deciduous first molars. This protocolhopefully encourages the first premolars toerupt before the canines, so that they can be<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 41 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

Interviewremoved easily, later permitting the caninesto erupt into the available arch space. In ourserial extraction protocol, ultimately four firstpremolars almost always are removed.19) Let’s move on to the treatment of ClassII malocclusion. If you have a choice as tothe optimal timing of Class II intervention,at what stage is the best treatment outcomesachieved?Today, evidence seems to indicate that themost effective time in the maturation sequence ofthe “generic” Class II patient who does not have asevere skeletal problem is during the circumpubertalgrowth period. The maturational stage can bedetermined best by the level of cervical vertebramaturation 41 (CVM) (Fig 8), as observed routinelyin the lateral headfilm. This method originally wasdeveloped by Don Lamparski 42,43 when he was anorthodontic resident at the University of Pittsburgh.This system was not used widely for the next 25years. We discovered a copy of the Lamparskithesis serendipitously in the late 1990s and havebeen refining the CVM method ever since. 41,44,45Dentitional stage, meaning the late mixed or earlypermanent dentition, also can be used to determinethe best time to initiate definitive Class II therapy.So in most such individuals, if it is reasonable wewill defer any type of Class II correction until thecircumpubertal growth period.If a patient has a “socially debilitating” ClassII malocclusion, however, then I would not hesitateto intervene in a 7-9 year old child, eitherwith a functional appliance such as the TwinBlock (Fig 9), the MARA appliance (Fig 10) orperhaps the cantilever version of the Herbst appliance.I would not expect, however, to have anabundant increase in mandibular growth duringthat early developmental stage. Rather, I wouldbe attempting to make the patient socially acceptablefrom a psychological standpoint, hopefullyleading to an improvement in his or heroverall self image.FIGURE 8 - CVM maturational stages. The six stages in cervicalvertebrae maturation. Stage 1 (CS-1): The inferior borders of thebodies of all cervical vertebrae are flat. The superior borders aretapered from posterior to anterior. Stage 2 (CS-2): A concavity developsin the inferior border of the second vertebra. The anteriorvertical height of the bodies increases. Stage 3 (CS-3): A concavitydevelops in the inferior border of the fourth vertebra. One vertebralbody has a wedge or trapezoidal shape. Stage 4 (CS-4): A concavitydevelops in the inferior border of the fourth vertebra. Concavities inthe lower borders of the fifth and sixth vertebrae are beginning toform. The bodies of all cervical vertebrae are rectangular in shape.Stage 5 (CS-5): Concavities are well defined in the lower bordersof the bodies of all six cervical vertebrae. The bodies are nearlysquare and the spaces between the bodies are reduced. Stage 6(CS-6): All concavities have deepened. The vertebral bodies arenow higher than they are wide. The largest amount of mandibularlengthening normally occurs between CS-3 and CS-4. 4120) In your publications over the last 15years, little emphasis has been assignedto the use of the Fränkel devices, in contrastto your earlier studies. What broughtabout this change to favor the use of TwinBlock and Herbst appliances?As I said earlier in the interview, I still considerthe functional appliance system developedby Rolf Fränkel to be the most biologically basedof any fixed or removable appliance. However,the technical manipulation of the appliance andthe difficulties in having the function regulatorFR-2 appliance (Fig 11) constructed properlystill are daunting. In addition, appliance breakageand problems with patient compliance havecaused the FR-2 to not be used often by mostorthodontists in North America.A few years ago, I polled six of the majororthodontic laboratories in the United Statesabout FJO appliance fabrication. The resultswere startling—more Herbst appliances (Fig12) are made today than all other functional<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 42 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

McNamara JA Jrappliances combined. Most popular among theother FJO devices are the Twin Block (Fig 9) andthe MARA (Fig 10) appliance and the bionator.About as many Fränkel appliances are made asbionators, but both are made less frequentlythan are the other appliances already mentioned.FIGURE 9 - The Twin Block appliance 3 shown here is the modifiedversion of the appliance that has a lower labial bow with acrylic toincrease the stability of the appliance during the transition to the permanentdentition.FIGURE 10 - The Mandibular Anterior Repositioning appliance (MARA). 63This appliance has stainless steel crowns on the first permanent molars.The attachments cause the patient to bite in a forward position.FIGURE 11 - The Fränkel Function Regulator FR-2. 3 This appliance ischaracterized by buccal shields that are connected by a series of wires.The lower labial pads are used to retrain the mentalis muscle in patientswith weak perioral musculature.21) For the last 20 or so years, you havetalked about the “spontaneous improvement”in Class II malocclusion followingmaxillary expansion in the mixed dentition.A study from the University of Illinois byTonya Volk et al, 54 published in 2010 in theAJO-DO, concluded that rapid maxillaryexpansion for spontaneous Class II correctiondoes not support “the foot in the shoetheory”. According to this study, improvementin Class II malocclusions occur inabout 50% of cases. What is your positiontoday in respect of the concept that whenthe mandible is free to move forward, positiveconditions are created for the mandibleto grow to its full extent?I have evaluated many treatments availablefor Class II malocclusion for over the last 40years and have participated in the evolution ofmany types of functional appliances includingthe FR-2 of Fränkel as well as the Bionator,Herbst and Twin Block appliances. In addition,my education at the University of California SanFrancisco was strong concerning the use of extraoraltraction. So I have substantial experiencewith different ways of correcting the sagittalposition of the maxillary and mandibular bonybases. I certainly did not anticipate finding thatClass II malocclusion improved spontaneouslyin many patients following expansion. A littlepersonal history is in order.We began using an acrylic splint expanderin 1981 (actually our protocol today remainsessentially unchanged from our early beginnings).We started by expanding the maxilla andplacing four brackets on the maxillary incisors,<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 43 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

InterviewAFIGURE 12 - The Stainless Steel Crown Herbst appliance. 3 This design is used most commonly in our practice. A rapid maxillary expansion appliance always isadded to the design not only to allow for expansion of the maxilla but also to stabilize the appliance. A) Maxillary view. B) Mandibular view.Bif needed, to eliminate rotations and spacing.Treatment was completed and a removablemaintenance plate (Fig 13) was delivered at thestart of the retention period; some remarkablepositive changes were noted post-treatment.Remember that at the end of active treatment,the maxillary dental arch intentionally had beenoverexpanded relative to the mandibular dentalarch. This relationship encouraged the patientto posture his or her jaw forward in order toocclude in the most functionally efficient way.After 6-12 months when follow-up records weretaken, many patients had substantial improvementin their sagittal occlusal relationship. Itshould be noted that discrepancies betweencentric occlusion and centric relation typicallywere not observed in the long-term.Even though I thought that I had uncovereda previously unrecognized phenomenon, I laterdiscovered that the spontaneous improvementin Class II relationship in fact had been noted inthe German literature since the early 1900s byKörbitz, 46 who originally postulated the “footin-shoe”theory 47 mentioned in your question(Fig 14). Even Norman Kingsley, considered bymany the “grandfather” of modern orthodontics,alluded to the expansion of the maxilla as a wayof correcting an excessive overjet as far back at1880. 48 But until recently, no clinical studies hadbeen carried out that addressed the “spontaneousimprovement” issue.In your question, you mentioned the work ofVolk and co-workers on this topic, published in2010. 54 Regardless of the findings of their study,the sample size was unacceptably small (N=13)and no control group was included. The questionunder consideration had to be addressed by amuch larger prospective clinical study (as wasstated in the last sentence of the Volk article),which we completed and just recently published.49 We have gathered prospectively cephalometricand dental cast data on every patientin our practice who underwent an early expansionprotocol, beginning in 1981. We stoppedcounting at 1,135 patients, a group that servedas the original sample. We then applied severalexclusionary rules to make sure that the patientswere at the same stage of dental developmentand did not have any additional appliances used(e.g., FJO, lip bumper). The final sample size(by chance) was precisely 500 patients who hadlateral cephalograms prior to treatment (about<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 44 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

McNamara JA JrFIGURE 13 - A removable maintenance plate with ball clasps on either sideof the second deciduous molars is used to stabilize the treated occlusion. 3FIGURE 14 - Maxillomandibular relationship as indicated by the “footand shoe” analogy of Körbitz. 46 A) The foot (mandible) is unable to bemoved forward in the shoe (maxilla) due to transverse constriction.B) A wider shoe will allow the foot to assume its normal relationship.After Reichenbach et al. 478.5 years old) and prior to Phase II treatment(about 12.5 years of age). We then gathereddata on 188 untreated subjects at the same twotime intervals. Both the treated and untreatedgroups were separated into a Class II group, anend-to-end group, and a Class I group.The results of our research are most easilyunderstandable by looking at a more detailedanalysis of a subset of individuals 50 that focusedon 50 Class II and end-to-end patients who werematched to 50 untreated subjects. The findingsof the latter study are presented in Figure 15.Positive skeletal and dentoalveolar treatmenteffects of RME were observed routinely; theseeffects are important in the serendipitoussagittal improvement of a Class II malocclusionafter therapy. Forty-six of the 50 patientsshowed positive molar changes equal to orgreater than 1 mm, compared to only 10 of 50in the control group. On the other hand, 40 ofthe control subjects had neutral or unfavorablemolar changes (less than +1 mm) between themixed and permanent dentitions, comparedto only 4 in the treated group. In other words,92% of the treated group spontaneously improvedtheir Class II molar relationship by onemillimeter or more, and almost 50% of treatedpatients presented with improvement in molarrelationship of 2 mm or greater, without anydefinitive Class II mechanics incorporated intothe protocol except for the transpalatal archworn during the transition to the permanentdentition. There also were significant skeletalimprovements from RME treatment includingan increase in mandibular length, pogonion advancement,and a reduction in the ANB angleand the Wits appraisal value three and half yearsafter active expansion therapy was completed.Observations in the control group in thisstudy confirm previously published data onlongitudinal observations of untreated subjectswith Class II malocclusions. 51-53 Arya and coworkers,52 for example, observed that all patientspresenting with a distal-step relationship of thesecond deciduous molars ultimately demonstrateda Class II relationship of the permanentmolars. In the current study, only 20% of thecontrol subjects improved their molar relationshipby 1 mm or 1.5 mm, which indicatesthat once a subject has a Class II malocclusion,without treatment they likely will remain witha Class II malocclusion in subsequent years.<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 45 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

InterviewThe favorable effects of RME therapy on anteroposteriorrelationships occur both in full-cusp ClassII and half-cusp Class II subjects. This expansionprotocol originally was recommended from clinicalanecdotal observations only in half-cusp ClassII subjects; 3 the results of the study by Guest andco-workers 50 indicate that spontaneous improvementof Class II malocclusion occurs equally in bothhalf-cusp and full-cusp Class II relationships. EvenVolk and co-workers 54 found improvement in ClassII relationship in 7 of their 13 subjects.The treatment protocol described above includesa Schwarz appliance (if needed), followed by anacrylic splint expander, and four brackets to align themaxillary incisors (if needed). The patient is given asimple maintenance plate (Fig 13) to maintain theachieved result. The lower arch is not maintainedfollowing the removal of the Schwarz appliance, butthe patient is evaluated for a lower lingual arch (Fig16) prior to the loss of the second deciduous molarsif an arch length deficiency is anticipated. The laststep in the protocol is the delivery of a transpalatalarch — TPA (Fig 17) — to maintain the leeway spaceduring the transition to the permanent dentition.22) Do you believe that the use of TPA inyour sample had an important role for thepositive outcome?Each component of this protocol serves a significantrole in improving the transverse and occlusalrelationships during the transition to the permanentdentition. Obviously the rotation of the uppermolars around the palatal root has a positive effect.23) What happen in those patients in whoman early expansion protocol is undertakenand spontaneous correction of the underlyingTotal molar change161412108642031516Untreated Control GroupRME Treated Group-4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4Increments of Molar Change (mm)FIGURE 15 - Spontaneous improvement in Class II molar relationshipfollowing rapid maxillary expansion in the early mixed dentition. Comparisonof amount of molar change from T2 - T1 for both groups. Ascore of “0” means that there was no change (i.e., 0 mm) in sagittalrelationship of the maxillary and mandibular first permanent molarsfrom the first to the second observation, a period of about 4 years.From Guest et al, 2010. 50315109 9131132711FIGURE 16 - The lower lingual arch is used during the late mixed dentitionto maintain the “leeway” space in the region of the erupting secondpremolar. 3 It also can be used during any stage of orthodontic treatmentto help in transverse arch coordination, especially in patients who haveundergone rapid maxillary expansion.FIGURE 17 - The transpalatal arch is used not only to maintain leewayspace, but also to rotate the maxillary first molars around their palatalroots and apply buccal root torque to these teeth. 3<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 46 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53

McNamara JA JrClass II molar relationship does not occur?Then what do you do?All patients receive comprehensive edgewisetreatment in the early permanent dentition. If apatient reaches the end of the mixed dentition orthe early permanent dentition and still has a Class IImalocclusion, a decision is made. If the patient hasa reasonable growth potential and the canine relationshipsare within 1-3 mm of Class I, then routinefixed appliance treatment is undertaken includingaggressive Class II elastic (¼”, 6 oz.) use. On theother hand, if the patient still has an end-to-end orworse Class II relationship, a stainless steel crownHerbst appliance (Fig 12) is used if mandibularskeletal retrusion is present. If the anteroposteriorposition of the mandible is within normal limits,then a Pendulum 55,56 (Fig 18) or Pendex (Fig 19)appliance may be recommended. In a few instances,the extraction of 2 maxillary first premolars maybe indicated. In any event, full fixed appliances areused to align the permanent dentition.It seems that the use of a Herbst appliance tobring the mandible forward would be in sharpcontrast to the approach taken by distalizing themaxillary dentition with a Pendex or Pendulumappliance; presumably these seemingly oppositetreatment approaches would result in very differenttreatment outcomes. A study by our groupthat compared the Pendex appliance to 2 types ofHerbst appliances 10 showed that even though theexpected differences in response in mandibulargrowth were noted during Phase I, the overalllength of the mandible was not statistically differentamong groups at the end of treatment; aslightly greater increase in lower anterior facialheight, however, did result after Pendex therapycombined with fixed appliances. Thus the presumeddifferences in treatment approach do notappear to be a great as assumed as before theresults were made available, again showing theimportance of evidence based treatment.24) What are your views on the use of functionalappliances in patients with verticalproblems?Functional appliance therapy in a high angleClass II patient is something I consider. My currenttreatment of choice is the stainless steelcrown Herbst appliance (Fig 12), which I haveused fairly routinely since the early 1990s. 10 Wealso have had good success when using the acrylicsplint variety of the Herbst appliance. 30 I see nosignificant contraindication to using either typeof appliance in a high angle patient.FIGURE 18 - The Pendulum appliance is used to distalize the maxillaryfirst molars, typically one side at a time. 3 This treatment is followed by theplacement of a Nance holding arch that is left in place until the premolarsand canines are distalized.FIGURE 19 - The Pendex appliance incorporates an expansion screwinto the palatal acrylic that is activated as necessary prior to molardistalization. 3<strong>Dental</strong> <strong>Press</strong> J Orthod 47 2011 May-June;16(3):32-53