QOF Plus Year 1 - Imperial College London

QOF Plus Year 1 - Imperial College London

QOF Plus Year 1 - Imperial College London

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Towards world class healthcare for all

<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on alcohol ............................................................................................................ 27Proposed indicators ........................................................................................................................... 27Background ........................................................................................................................................ 27Priority and relevance to national policy ........................................................................................... 28Prevalence of condition ..................................................................................................................... 28Associated morbidity and mortality .................................................................................................. 28Local context ...................................................................................................................................... 29Review of evidence to support the proposed indicators ................................................................... 29Degree of perceived professional consensus .................................................................................... 30Degree of perceived support from patients and carers .................................................................... 30Impact on health inequalities ............................................................................................................ 30Health impact .................................................................................................................................... 30Workload and training implications .................................................................................................. 31References ......................................................................................................................................... 31<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on smoking .......................................................................................................... 33Proposed indicators ........................................................................................................................... 33Background ........................................................................................................................................ 33Priority and relevance to national policy ........................................................................................... 34Prevalence of condition ..................................................................................................................... 34Associated morbidity and mortality .................................................................................................. 34Local context ...................................................................................................................................... 35Review of evidence to support proposed indicators ......................................................................... 35Degree of perceived support from professionals .............................................................................. 35Degree of perceived support from patients and carers .................................................................... 35Impact on health inequalities ............................................................................................................ 35Health impact .................................................................................................................................... 36Workload and training implications .................................................................................................. 36References ......................................................................................................................................... 37<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on smoking in pregnancy .................................................................................... 39Proposed Indicators ........................................................................................................................... 39Background ........................................................................................................................................ 39Priority and relevance to national policy ........................................................................................... 39Prevalence of condition ..................................................................................................................... 40Associated morbidity and mortality .................................................................................................. 40Local context ...................................................................................................................................... 40Evidence to support the proposed indicators ................................................................................... 41Degree of perceived professional consensus .................................................................................... 41Degree of perceived support from patients and carers .................................................................... 41Impact on health inequalities ............................................................................................................ 41Health impact .................................................................................................................................... 42Workload and training implications .................................................................................................. 42References ......................................................................................................................................... 43

<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on breastfeeding ................................................................................................. 45Proposed Indicators ........................................................................................................................... 45Background ........................................................................................................................................ 45Priority and relevance to national policy ........................................................................................... 46Prevalence of condition ..................................................................................................................... 46Associated morbidity and mortality .................................................................................................. 46Local context ...................................................................................................................................... 47Review of evidence to support the proposed indicator .................................................................... 47Degree of perceived professional consensus .................................................................................... 49Degree of perceived support from patients and carers .................................................................... 49Impact on health inequalities ............................................................................................................ 49Health Impact .................................................................................................................................... 49Workload and training implications .................................................................................................. 49References ......................................................................................................................................... 50<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on ethnicity.......................................................................................................... 51Proposed Indicators ........................................................................................................................... 51Background ........................................................................................................................................ 51Priority and relevance to national policy ........................................................................................... 52Demography ...................................................................................................................................... 52Associated Morbidity and Mortality .................................................................................................. 53Local context ...................................................................................................................................... 53Review of evidence to support proposed indicators ......................................................................... 53Degree of perceived support from professionals .............................................................................. 54Degree of perceived support from patients and carers .................................................................... 54Impact on health inequalities ............................................................................................................ 54Health impact .................................................................................................................................... 54Workload and training implications .................................................................................................. 55References ......................................................................................................................................... 55<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on records ........................................................................................................... 57Proposed indicators ........................................................................................................................... 57Background ........................................................................................................................................ 57Priority and relevance to national policy ........................................................................................... 58Prevalence of conditions ................................................................................................................... 58Local context ...................................................................................................................................... 59Review of evidence to support the proposed indicators ................................................................... 60Degree of perceived professional consensus .................................................................................... 61Degree of perceived support from patients and carers .................................................................... 61Impact on health inequalities ............................................................................................................ 61Health impact .................................................................................................................................... 61Workload and training implications .................................................................................................. 62References ......................................................................................................................................... 63

<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on new patient screening .................................................................................... 65Proposed indicator ............................................................................................................................ 65Background ........................................................................................................................................ 65Priority and relevance to national policy ........................................................................................... 66Prevalence of condition ..................................................................................................................... 66Associated morbidity and mortality .................................................................................................. 66Local context ...................................................................................................................................... 66Review of evidence to support the proposed indicators ................................................................... 67Degree of perceived professional consensus .................................................................................... 67Degree of perceived support from patients and carers .................................................................... 67Impact on health inequalities ............................................................................................................ 67Health impact .................................................................................................................................... 67Workload and training implications .................................................................................................. 68References ......................................................................................................................................... 68<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on patient information ........................................................................................ 69Proposed indicators ........................................................................................................................... 69Background ........................................................................................................................................ 69Priority and relevance to national policy ........................................................................................... 71Local context ...................................................................................................................................... 71Review of evidence to support the proposed indicators ................................................................... 72Degree of perceived professional consensus .................................................................................... 72Degree of perceived support from patients and carers .................................................................... 73Impact on health inequalities ............................................................................................................ 73Health impact .................................................................................................................................... 73Workload and training implications .................................................................................................. 74References ......................................................................................................................................... 75<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on patient experience ......................................................................................... 77Proposed indicators ........................................................................................................................... 77Background ........................................................................................................................................ 78Priority and relevance to national policy ........................................................................................... 79Local context ...................................................................................................................................... 79Review of evidence to support the proposed indicators ................................................................... 80Degree of perceived professional consensus .................................................................................... 82Degree of perceived support from patients and carers .................................................................... 82Impact on health inequalities ............................................................................................................ 82Health impact .................................................................................................................................... 82Workload and training implications .................................................................................................. 82References ......................................................................................................................................... 83

<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on patient safety ................................................................................................. 85Proposed indicators ........................................................................................................................... 85Background ........................................................................................................................................ 86Priority and relevance to national policy ........................................................................................... 87Local context ...................................................................................................................................... 87Review of evidence to support the proposed indicators ................................................................... 88Degree of perceived professional consensus .................................................................................... 89Degree of perceived support from patients and carers .................................................................... 89Impact on health inequalities ............................................................................................................ 90Health impact .................................................................................................................................... 90Workload and training implications .................................................................................................. 90References ......................................................................................................................................... 90Training and support requirements for <strong>QOF</strong>+ .......................................................................... 91Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 91Training and support requirements for selected existing <strong>QOF</strong> indicators ......................................... 91Training and support requirements for new <strong>QOF</strong>+ indicators .......................................................... 92

Appendix 1 – Background to the <strong>QOF</strong>+ development process ..................................................... 100Composition of the <strong>QOF</strong>+ development group ............................................................................... 100Process employed by the <strong>QOF</strong>+ development group ...................................................................... 100Approach to development of the scheme ....................................................................................... 100Appendix 2 – Methodology for the extension of existing clinical <strong>QOF</strong> targets .............................. 102Selection of candidate existing indicators for revised upper thresholds ......................................... 102Methodology for revised target setting for existing clinical indicators ........................................... 103Methodology for point allocation for existing clinical indicators .................................................... 106Minimum attainment thresholds .................................................................................................... 109Exception reporting ......................................................................................................................... 110List turnover ..................................................................................................................................... 115References ....................................................................................................................................... 115Appendix 3 – Current levels of attainment and exception reporting for existing clinical indicators 116Purpose of these data ...................................................................................................................... 116Data sources .................................................................................................................................... 116Using the graphs .............................................................................................................................. 117Asthma 6 .......................................................................................................................................... 118BP 5 .................................................................................................................................................. 119CHD 6 ............................................................................................................................................... 120CHD 8 ............................................................................................................................................... 121CHD 10 ............................................................................................................................................. 122CS 1 .................................................................................................................................................. 123DM 12 .............................................................................................................................................. 124DM 17 .............................................................................................................................................. 125DM 20 .............................................................................................................................................. 126MH 6 ................................................................................................................................................ 127Stroke 6 ............................................................................................................................................ 128Stroke 8 ............................................................................................................................................ 129Appendix 4 – Methodology for the design and development of the new indicators for <strong>QOF</strong>+ ...... 130Methodology for the creation of new indicator areas long list ....................................................... 130Consultation with local stakeholders to select priority areas for the development of <strong>QOF</strong>+indicators ......................................................................................................................................... 132Methodology for the development of new indicators .................................................................... 134Consultation with local practices ..................................................................................................... 135Assessment of new indicators ......................................................................................................... 135Response to feedback on proposed new indicators ........................................................................ 136Final consultation with local practices ............................................................................................. 137Methodology for point allocation for the new <strong>QOF</strong>+ indicators ..................................................... 137Communication with the PCT’s health informatics team ................................................................ 138Appendix 5 – Methodology for the development of the training and support package ................. 140Development of the training and support package ......................................................................... 140Results of data analysis of practice achievement for selected existing <strong>QOF</strong> indicators .................. 141Results of practice training and support needs assessment ........................................................... 141Appendix 6 – Summary of the <strong>QOF</strong>+ scheme ............................................................................. 142

CreditsProject boardJosip CarMiles FreemanYvonne OdegbamiAzeem MajeedArti MainiBecky WellburnChristopher HuckvaleSian ClaptonHakan AkozekXavier YiboweiProject Executive, Academic & Clinical leadjosip.car@hf-pct.nhs.ukProject Executive, Management leadmiles.freeman@hf-pct.nhs.ukProject ManagerAcademic and Clinical AdvisorClinical <strong>QOF</strong>+ CoordinatorNon-clinical <strong>QOF</strong>+ Coordinator<strong>QOF</strong>+ AnalyticsProject Finance OfficerChief Information OfficerHead of InformaticsProject governanceHakan AkozekJosip CarFrances DonellyMiles FreemanChristopher MillettAlison WilliamsDagmar ZeunerDeputy Director of Informatics and QualityPEC Chair & Medical DirectorProject Director for Primary Care QualityDirector of Primary Care and CommissioningConsultant in Public HealthDirector of FinanceDirector of Public HealthContributorsRiyadh Alshamsan (Doctoral researcher in health economics)Josip Car (PEC Chair & Medical Director, GP and Director of e·Health Unit)Miles Freeman (Interim Director of Primary Care)Christopher Huckvale (Honorary research associate in e·Health)Elizabeth Koshy (Academic GP & honorary clinical research fellow)Arti Maini (Academic GP & honorary clinical research fellow)Azeem Majeed (Head of Department and Professor of Primary Care)Christopher Millett (Academic Consultant in Public Health)David Morley (Health informatics team)Sam Nemonique (GP on clinical leadership training)Shanker Vijayadeva (GP & honorary clinical research fellow)Jill Waddingham (<strong>QOF</strong>+ Resource Pack Co-ordinator)Becky Wellburn (Head of Primary Care Commissioning)Xavier Yibowei (Health informatics team)Dominik Zenner (GP and Specialist Registrar in Public Health)Dagmar Zeuner (Director of Public Health)

Delphi local stakeholder consultation groupJosip Car, Miles Freeman, Sheraz Khan, Paul Skinner, Tony Willis, Dagmar ZeunerHealth informatics teamHakan Akozek, Christopher Huckvale, David Morley, Richard McSharry, Xavier Yibowei

AcknowledgementsWe are indebted to the valuable contribution made by the following individuals and groups.Dr Ike AnyaDr Mark AshworthProfessor Richard BakerPatricia CaddenChristopher CorfieldGloria-Anne CoxDr Tim DoranProfessor Colin DrummondRachel HaffendenLynne JonesProfessor Helen LesterChristine McCruddenProfessor Martin RolandProfessor Aziz SheikhDr Michael SoljakTom StevensonDr Richard WilliamsConsultant in Public Health, NHS Hammersmith and FulhamKings <strong>College</strong> <strong>London</strong>University of LeicesterSenior Substance Misuse Commissioning Manager<strong>London</strong> Borough of Hammersmith and FulhamChief Pharmacist, NHS Hammersmith and FulhamHammersmith and Fulham TB Action GroupUniversity of ManchesterKings <strong>College</strong> <strong>London</strong>Hammersmith and Fulham TB Action GroupDesignated Nurse for Child ProtectionHammersmith and FulhamUniversity of ManchesterHammersmith and Fulham TB Action GroupUniversity of ManchesterUniversity of Edinburgh<strong>Imperial</strong> <strong>College</strong>, <strong>London</strong>Head of Communications, NHS Hammersmith and FulhamLambeth PCTThe NHS Information CentreGPRD Group, Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory AgencyProfessional Executive Committee (PEC), NHS Hammersmith and FulhamPlanning and Strategy Group, NHS Hammersmith and FulhamWe would like to thank all the general practices of Hammersmith and Fulham who participated in the<strong>QOF</strong>+ consultation process.In addition, we would like to acknowledge the work of the <strong>QOF</strong> Review; a collaboration between theUniversities of Birmingham and Manchester, the Society of Academic Primary Care and the Royal <strong>College</strong>of General Practitioners which is led by co-directors Professors Richard Hobbs (UoB) and Helen Lester(UoM). We based the structure of the <strong>QOF</strong>+ reports on that used in the reports produced through the<strong>QOF</strong> Review.

Foreword<strong>QOF</strong> <strong>Plus</strong> has high ambition - to deliver world class healthcare. It focuses on helping peoplelive healthier and longer lives, and above all aims to dramatically reduce health inequalities.To achieve this vision of better care for all <strong>QOF</strong> <strong>Plus</strong> builds on existing systems for quality in primary careand uses the best international evidence to extend these. We know that improving quality is not easy. Yetwe also know that it is possible when priorities and the approach to change are right. With <strong>QOF</strong> <strong>Plus</strong> wehave focused on what matters and makes a difference for both patients and clinicians. We have built intothe implementation the best evidence on support for quality improvement. In particular, we want toensure that individual practices and clinicians are enabled in transforming their clinical practice to make itof consistently high quality.This publication is accompanied by a support resource pack, guidance on business and financial rules,EMIS and Vision templates for health monitoring, details of a series of training events, visits andworkshops. Most importantly, <strong>QOF</strong> <strong>Plus</strong> is supported by a committed clinical, academic and managementteam which aims to provide a range of multimodal supportive strategies to address, in real time, areas ofchallenge. This is the most significant investment into quality improvement in primary care since theintroduction of <strong>QOF</strong>.This innovative scheme, developed jointly with experts in our local Department of Primary Care and SocialMedicine at <strong>Imperial</strong> <strong>College</strong>, combines a strong evidence-based approach with meaningful engagementand consultation with local practices and stakeholders. <strong>QOF</strong> <strong>Plus</strong> has been designed in line with nationalguidance and addresses a range of important national and local health service priorities. It builds on theanalysis of the public health needs of Hammersmith and Fulham, and on what local people have told usthey want.Advice offered by national and international experts in health care quality improvement has played asignificant role in helping determine the vision and implementation strategy for <strong>QOF</strong> <strong>Plus</strong>, ensuring thatwe learn from past experience in the field. The key individuals involved in designing and developing <strong>QOF</strong><strong>Plus</strong> believe passionately in – and are fully committed to – the principles embodied by the scheme,namely achieving excellence in healthcare for all people and reducing health inequalities; ensuring thehealthcare needs of those most vulnerable are addressed. This team is championing the scheme and will,in partnership with patients and colleagues in primary care, work to make it a success.I am sincerely grateful to all that have contributed to this important project that brings new dynamism toprimary care embodying some of the key principles of Lord Darzi’s Next Stage Review. I believe <strong>QOF</strong> <strong>Plus</strong>will make a real difference to the people of Hammersmith and Fulham. I also hope that this work willmake a valuable contribution to the current national debate about the future direction of <strong>QOF</strong>, and serveas a model for other PCTs wishing to initiate similar schemes.Sarah WhitingCEO, NHS Hammersmith and Fulham, December 2008

Executive summaryIntroductionPrevious work has highlighted several limitations of the national Quality and Outcomes Framework (<strong>QOF</strong>)including insufficient focus on health outcomes, primary prevention, prioritised local health needs andbenefits. <strong>QOF</strong> may not encourage practices in reaching the more challenging patients, as practices do notreceive further incentives once they have received the upper payment threshold. It is anticipated thatintroduction of a local <strong>QOF</strong> will help address these limitations.AimsThis document describes a joint venture by NHS Hammersmith and Fulham and the Department ofPrimary Care and Social Medicine at <strong>Imperial</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>London</strong> to design and develop a local <strong>QOF</strong> forHammersmith and Fulham (<strong>QOF</strong>+) which is in line with current national guidance, developed through theprocess of effective clinical engagement and which aims to have a greater emphasis on prevention,address local needs, accelerate improvement and reduce inequity.MethodologyEngagement with local practices and other local provider services, feedback from patients and discussionswith national and international experts in health care quality improvement provided insights whichinformed the development of the scheme.A number of existing <strong>QOF</strong> indicators were identified as candidates that might benefit from additionalincentivisation through the provision of revised upper targets. Indicator selection was weighted towardsthose whose attainment confers significant potential health benefits at a population level and wherecurrent attainment in Hammersmith and Fulham is below that seen nationally.Potential sources for new indicator areas were identified and prioritised on the basis of being both localand national priorities. These were subjected to a structured consultation with local stakeholders to selectareas for indicator development for the first year of the scheme through a consensus process.Literature reviews of the evidence base were undertaken for each selected indicator area to informdevelopment of indicators.Proposed new indicators were assessed using the Organisation for Economic Cooperation andDevelopment (OECD) criteria of importance, scientific soundness and feasibility. Each indicator was alsoassessed for clarity. This assessment was informed by the views of local practices, a local stakeholderpanel (through a structured consultation with the aim of achieving consensus for the clinical and recordsdomains), local provider services and national and international experts in the proposed indicator areas.

Like <strong>QOF</strong>, <strong>QOF</strong>+ includes a combination of all-or-northing and payment stage indicators, re-uses theconcept of exception reporting and determines remuneration using a system of population andprevalence-weighted point allocation. The PCT Health Informatics Team was consulted to ensure thatproposed indicators would work within primary care IT systems.The development of a training and support package to support <strong>QOF</strong>+ was informed by consultation withlocal and national experts, analysis of data on achievement for existing <strong>QOF</strong> for individual practices, and atraining and support needs assessment conducted among all local practices.OutcomesThrough <strong>QOF</strong>+, practices will be rewarded with <strong>QOF</strong>+ points for achievement of higher thresholds for aselected number of existing national <strong>QOF</strong> indicators including the following:Asthma 6, BP 5, CHD 6, CHD 8, CHD 10, CS 1, DM 12, DM 17, DM 20, MH 6, Stroke 6, Stroke 8.Additionally, practices will be rewarded for achievement of new <strong>QOF</strong>+ indicators which have beendeveloped in clinical and non-clinical domains covering the following areas: Cardiovascular DiseasePrimary Prevention, Alcohol, Smoking Cessation (including Smoking in Pregnancy) Breastfeeding,Ethnicity, Records, New Entrant Screening (for Tuberculosis), Patient Information, Patient Experience andPatient Safety.Anonymised medical records of all registered patients will be stored centrally by the PCT through the useof the APOLLO IT system by practices. This will enable analysis of performance, improved practiceprofiling, equity assessment using patient-level data, and provision of monthly feedback of performanceto practices, as part of a wider training and support package which has been developed to support <strong>QOF</strong>+.© Copyright NHS Hammersmith and Fulham 2008© Copyright eHealth unit, Department of Primary Care and Social Medicine, <strong>Imperial</strong> <strong>College</strong> 2008

Support with <strong>QOF</strong>+If you have a problem with any of the IT aspects of <strong>QOF</strong>+, please contact:This service is available to NHS Hammersmith and Fulham practices only.Additional <strong>QOF</strong>+ resources and content are available to download from:requires N3 connectionFor all other enquiries:For general help and support with any aspect of <strong>QOF</strong>+, there is a dedicated email address:Hammersmith and Fulham practices can also contact their commissioning manager.

Introduction to <strong>QOF</strong>+Improving the quality of primary care services inHammersmith and FulhamContextThe purpose of this paper is to provide the rationale and describe the process for implementing amajor quality improvement initiative for primary care services in Hammersmith and Fulham,called <strong>QOF</strong>+. The initiative has been developed by NHS Hammersmith and Fulham in partnershipwith the eHealth unit of the Department of Primary Care & Social Medicine at <strong>Imperial</strong> <strong>College</strong><strong>London</strong>.NHS Hammersmith and Fulham has identified quality improvement in primary care as a key localpriority. The PCT has earmarked over £2 million annual funding to implement a comprehensivelocal financial incentive scheme (<strong>QOF</strong>+) over the next three years (2008/09, 2009/10, 2010/11).The aims of this scheme are to achieve a step-change in quality and address local priorities.Subject to a positive evaluation, this funding is likely to be extended beyond this period.Defining and measuring the quality of healthcareThere are currently no internationally agreed definitions of healthcare quality. Maxwell (1983)offers six dimensions of quality in healthcare including appropriateness, equity, accessibility,effectiveness, acceptability and efficiency. One of the most widely adopted definitions of qualityis provided by the Institute of Medicine: "The degree to which health services for individuals andpopulations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with currentprofessional knowledge” (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Performance indicators are designed tomeasure the extent to which health services meet this goal (Majeed, 1995).There has been an increased interest in measuring the quality of care over the past decade. Inparallel, there have been significant developments in databases, both administrative and clinical,which have enabled collection of routine information on quality. These factors have significantlyinfluenced the development and implementation of performance indicators (Majeed et al., 2007).International evidence underlines the importance of high quality primary care in achieving aneffective and efficient health care system and in improving population health (Starfield, 2001).Whilst recent investment in quality initiatives in the UK has led to considerable improvements inprimary care, the quality of service provision remains variable in many areas (Gray et al., 2007;Hippisley-Cox et al., 2004).1

The quality and outcomes framework (<strong>QOF</strong>)April 2004 saw the introduction of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (<strong>QOF</strong>) as part of theNew Contract for General Practitioners where pay was linked to performance with the purpose ofdriving up standards for primary care. The framework includes quality and performanceindicators in a number of domains, including clinical, organisational and patient experience, aswell as additional areas such as cervical screening (Roland et al., 2004). The quality measures in2004 were largely drawn from existing national guidelines, and were designed to reflect widelyaccepted standards of clinical care. The contract was significantly revised in 2006 following arenegotiation, with the addition of nine areas, changes in indicators and increased thresholds forpayment.Impact of the quality and outcomes frameworkGPs have achieved high scores in the <strong>QOF</strong> in each of the first three years of the scheme. In 2006-07 practices in England achieved an average of 954.5 points, (95.5 percent of the 1,000 available).This compares with an average achievement of 96.2 per cent in 2005-06 and 91.3 percent in2004-05 against the 1,050 points then available (National Audit Office, 2008).Early data suggests the introduction of the <strong>QOF</strong> has shown moderate improvements in outcomesfor patient care in some long term conditions such as asthma and diabetes, but not for otherssuch as coronary heart disease (Campbell et al., 2007).Future changes to the quality and outcomes frameworkBuilt into the new GMS contract is the expectation that <strong>QOF</strong> will evolve over time. The focus inthe first few years of <strong>QOF</strong> has been on process measures as a first step towards achieving goodoutcomes. Lester (2008) further comments that “In future, perhaps pay for performance schemesshould be actively designed with health inequalities in mind.”As part of the NHS Next Stage Review, the Department of Health announced proposals for furtherdeveloping the Quality and Outcomes Framework (<strong>QOF</strong>) including an independent andtransparent process for developing and reviewing indicators. The Review outlined plans to discusswith the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and with professional andpatient groups how this new process should work, and to explore the possibility of allowing PCTsgreater flexibility to select indicators (from a national menu) that reflect local healthimprovement priorities (Darzi, 2008).The National Audit Office (NAO) report on GP contract modernisation (National Audit Office2008) recommended that the Department of Health should:develop a long term strategy to support yearly negotiations on <strong>QOF</strong>, anddevelop <strong>QOF</strong> based on patients’ needs and in a transparent way,base the strategy more on outcomes and cost effectiveness, andagree to allocate a proportion of <strong>QOF</strong> indicators for local negotiation at Strategic HealthAuthority (SHA) or PCT level.2

The Department of Health is currently consulting on the proposal to ask NICE to oversee a newindependent, transparent and objective process for developing and reviewing <strong>QOF</strong> clinical andhealth Improvement indicators for England from 1 April 2009 (DoH, 2008).The Department of Health is also consulting on the proposal that Primary Care Trusts (PCTs)should have flexibility to select additional indicators from the NICE menu to reflect localpriorities.The Royal <strong>College</strong> of General Practitioners is planning to develop and roll out nationally by 2010an accreditation scheme for GP practices. It is proposed that this scheme will serve as a vehicle todrive organisational quality improvement, and this is likely to have a significant impact on thearrangements for incentivising organisational quality through the Quality and OutcomesFramework (National Primary Care Research and Development Centre, 2008).Limitations of the quality and outcomes frameworkThe National Audit Office (2008) and Fleetcroft el al. (2006) have highlighted a number oflimitations of the national <strong>QOF</strong>: incentivised clinical areas in <strong>QOF</strong> may not reflect local populationhealth needs, indicators are insufficiently focused on health outcomes, and rewards areinsufficiently aligned with prioritised health need or health benefit.Payment thresholds have arguably been set too low, so that standards recommended in nationalclinical guidelines are not being achieved for most patients (Fleetcroft et al., 2008). There is someevidence that improvements in care associated with <strong>QOF</strong> have not occurred in all groups, e.g.ethnic minorities, thereby potentially worsening health inequalities (Gray et al., 2007). Qualityindicators in <strong>QOF</strong> have not been sufficiently weighted towards primary prevention (Darzi, 2008).In addition, Short (2007) notes discrepancies between <strong>QOF</strong> and NICE guidance in certain areasand comments that “there needs to be some clarity and stream-lining of guidance betweenprimary care and major clinical governing bodies.” NICE is currently examining the fit between<strong>QOF</strong> and the evidence-based NICE guidelines (Leech, 2008).The role of healthcare in addressing health inequalitiesThe principle of social justice incorporated into the Physician’s Charter (Medical ProfessionalismProject: ABIM Foundation 2002) states that “the medical profession must promote justice in thehealthcare system” and that physicians should “work actively to eliminate discrimination inhealthcare, whether based on race, gender, socio-economic status, ethnicity, religion or anyother social category.” One of the professional responsibilities included in the Physician’s Charterinvolves improving access to care. This requires that physicians must “individually and collectivelystrive to reduce barriers to equitable health care.”3

Effect of measurement on health inequalityMant (2008) comments that “in everyday clinical practice, variability in usual care matters mostat the tail-end of the distribution where poor care can lead to adverse outcomes includingavoidable death.” Evidence from epidemiological studies suggest that while effective regularmechanisms for dealing with poor care are essential, a more effective approach is to developstrategies for raising average performance, and therefore shifting the whole distribution (Rose etal., 1990). An example of this is the introduction of cervical smear targets for UK general practicesin 1990. The highest targets were achieved rapidly by practices in affluent areas, and this resultedin an initial widening of the health inequality gap. However, practices in more deprived areascaught up over the next few years, thereby reducing inequality (Baker et al., 2003; Middleton etal., 2003). This phenomenon has been termed the inverse equity hypothesis (Victora et al., 2000).This hypothesis predicts that the benefits of new public health interventions are initiallyexperienced by the wealthier sector of the population and later by the poor, increasing theinequity ratio. However, once the poor have experienced benefits and a ceiling effect is reachedin the richer population, the inequity ratio which initially increases, then decreases.Although the Quality and Outcomes Framework was not designed to tackle health inequalities(Roland, 2004), there is evidence of the inverse equity hypothesis being relevant to <strong>QOF</strong>. Data isnow emerging which suggests that from a longer term perspective, more equitable healthcare isbeing generated following the introduction of <strong>QOF</strong> (Lester, 2008). Ashworth et al. (2008) assessedthe effects of social deprivation on levels of BP monitoring and control using data from over 97%of practices in England over the first three years of the <strong>QOF</strong>. They found that:“Since the reporting of performance indicators for primary care and the incorporation ofpay for performance in 2004, blood pressure monitoring and control have improvedsubstantially. Improvements in achievement have been accompanied by the neardisappearance of the achievement gap between least and most deprived areas.”Doran et al. (2008) looked at overall achievement in 48 of the clinical indicators in <strong>QOF</strong> and foundthat median achievement score increased across the board, with the gap in median achievementbetween practices in the most and least deprived areas reducing considerably.The evidence suggests that “low scoring practices in deprived areas also seem just as able toimprove the quality of their care (as measured by the Framework) as low scoring practices inmore affluent areas” (Lester, 2008). Lester (2008) further comments that:“Overall, the financial incentives seem to have reached areas of high need relativelyeffectively for most targets. An important subsidiary message is the need to take a longterm view when interpreting the effects of quality measures on health inequalities.”However, there remains concern that <strong>QOF</strong> may not encourage practices in reaching the morechallenging, hard-to-reach patients, as practices do not receive further incentives once they haveachieved the 90% upper threshold for payment (National Audit Office, 2008). This meanspractices can receive maximum points and payment for every clinical indicator before all eligiblepatients receive indicated care. Fleetcroft et al. (2008) comment that this can result in an‘incentive ceiling effect’ with associated reductions in health gains, and state that “there may beno rationale for maximum target thresholds to be set below 100% as there are comprehensivereasons for exception reporting any patient who would not theoretically benefit from theindicated care”. Setting and rewarding achievement of higher thresholds for selected existing4

<strong>QOF</strong> indicators may therefore help to address this issue, with the aim of achieving additionalhealth gains in a more challenging group of patients.Why have a local <strong>QOF</strong>?Local Enhanced Services (LES) already provide scope for local development within the GMScontract. The purpose of these is to allow PCTs to tackle local problems not addressed in thenational <strong>QOF</strong>. These may include a greater emphasis on prevention and strategies designed toreduce inequity. It is anticipated that introduction of a local <strong>QOF</strong> would confer a number ofadvantages, including more robust performance reporting, mainstreaming quality throughtemplates and coverage of a greater number of areas.The concept of developing a local <strong>QOF</strong> has recently received backing from the National AuditOffice (2008) and the NHS Next Stage Review (Darzi, 2008).Development and implementation of a local <strong>QOF</strong> may also contribute to PCTs fulfilling theirfunctions as World Class Commissioners. The Department of Health describes World ClassCommissioners as being “central to a self-improving NHS. They will operate as learningorganisations, seeking and sharing knowledge and skills. World class commissioners will also bestimulating provider and clinical innovation through improvements in experienced quality, accessand outcomes” (DoH, 2008). As part of this commissioning process, PCTs are required to “investlocally to achieve the greatest health gains and reductions in health inequalities, at best value forcurrent and future service users”.The World Class Commissioning programme (DoH, 2008) outlines a series of competencies whichcommissioners will need to reach world class status. These are:locally lead the NHSwork with community partnersengage with public and patientscollaborate with cliniciansmanage knowledge and assess needsprioritise investmentstimulate the marketpromote improvement and innovationsecure procurement skillsmanage the local health systemmake sound financial investments5

How might a local <strong>QOF</strong> operate in practice?There is ongoing debate about how a local <strong>QOF</strong> could work in practice. The Department of Healthhas proposed that to help address local health needs more effectively, PCTs should be able toselect local indicators from a national menu of indicators, for use in local voluntary incentiveschemes (DoH, 2008).An alternative is for indicators to be developed locally by PCTs. However, there are practicallimitations associated with this approach including:the need for technical expertise in the development of evidence-based indicators andbusiness rules for extraction of clinical data from GP systems;the IM&T support required to extract data from clinical systems and to link this withpayment calculations (DoH, 2008).Why have a local <strong>QOF</strong> for Hammersmith and Fulham?Evaluations of recently introduced LES and local Shared Care schemes (including CVD PrimaryPrevention, Smoking Cessation and Alcohol) in Hammersmith and Fulham highlighted a numberof problems with these schemes, in terms of their complexity and design and the level of uptakeby practices. These highlight a need for widespread implementation in a way that is easilyunderstood. There is also a need to reduce health inequalities and recognition that <strong>QOF</strong> may be avehicle to achieve this. Although it has been proposed that PCTs should have flexibility to selectlocal indicators from a national menu published by NICE, the infrastructure required to supportdevelopment of local <strong>QOF</strong>s through this approach is not anticipated to be in place until 2011/12at the earliest (DoH, 2008). It was therefore proposed that NHS Hammersmith and Fulham woulddevelop a local <strong>QOF</strong> scheme to run initially for 3 years from 2008/9-2010/11, with technicalexpertise in indicator development being provided by the Department of Primary Care and SocialMedicine at <strong>Imperial</strong> <strong>College</strong> <strong>London</strong> in conjunction with national and international experts in thisfield, and IM&T support being provided by the PCT’s Health Informatics Team.The need for clinical engagementEffective local clinical engagement is crucial to the success of service improvement initiatives andits integral role has been highlighted in the competencies of World Class Commissioning (DoH,2008) and by The NHS Alliance (2003) which states that “front-line clinical staff should beeffectively involved in redesign, service provision and in ensuring services are used costeffectively.”The NHS Alliance further highlights that the engagement of front-line professionalsat a strategic level would allow PCTs to draw on a bank of untapped knowledge resulting from thewider experiences of primary care. The involvement of local practices in helping shape <strong>QOF</strong>+ wastherefore seen as a central element of the design and development of the scheme.6

AimsThis paper describes the design and development of a local <strong>QOF</strong> for Hammersmith and Fulhamwhich is in line with current national guidance, developed through the process of effective clinicalengagement and which aims to have a greater emphasis on prevention, address local needs,accelerate improvement and reduce inequity.ReferencesAshworth M, Medina J, Morgan M (2008). Effect of social deprivation on blood pressure monitoringand control in England: a survey of data from the "quality and outcomes framework." British MedicalJournal 337:a2030Baker D, Middleton E (2003) Cervical screening and health inequality in England in the 1990s.Epidemiological Community Health 57:417-23.Campbell S, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Middleton E, Sibbald B, Roland M. Quality of Primary Care inEngland with the Introduction of Pay for Performance (2007). New England Journal of Medicine357:181-90.Darzi A (2008) High Quality Care for All, the final report of the NHS Next Stage Review Final Report byLord Darzi The Stationary Office. <strong>London</strong>Department of Health (2008) Developing the Quality and Outcomes Framework: Proposals for a new,independent process. [Online, Accessed November 03 2008] Available at:http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Consultations/Liveconsultations/DH_089778Department of Health (2008) World Class Commissioning. [Online, Accessed August 10 2008] Availableat:http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Managingyourorganisation/Commissioning/Worldclasscommissioning/index.htm7

Doran T, Fullwood C, Kontopantelis E, Reeves D (2008). Effect of financial incentives on inequalities inthe delivery of primary clinical care in England: analysis of clinical activity indicators for the quality andoutcomes framework. Lancet 372:728-36Fleetcroft, R and Cookson, R (2006) Do the incentive payments in the new NHS contract for primarycare reflect likely population health gains? Journal of Health Care Research and Policy 11:27–31.Fleetcroft R, Steel N, Cookson R, Howe A (2008) “Mind the gap!" Evaluation of the performance gapattributable to exception reporting and target thresholds in the new GMS contract: National databaseanalysis. BMC Health Services Research 8: 131Gray J, Millett C, Saxena S, Netuveli G, Khunti K, Majeed A (2007) Ethnicity and Quality of DiabetesCare in a Health System with Universal Coverage: Population-Based Cross-sectional Survey in PrimaryCare. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22:1317-20.Hippisley-Cox J, O'Hanlon S, Coupland C (2004). Association of deprivation, ethnicity, and sex withquality indicators for diabetes: population based survey of 53 000 patients in primary care. BritishMedical Journal 329:1267-9.Institute of Medicine (2001). Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.Washington, DC: National Academy PressLeech P (2008) <strong>QOF</strong>; Key benefits and challenges in long term conditions management.[Online, Accessed August 10 2008] Available at:www.pcc.nhs.uk/events/uploads/dr_philip_leech_17th_october.pptLester H (2008) The UK Quality and outcomes framework. British Medical Journal 337:a2095Mant D (2008) The problem with usual care. British Journal of General Practice 58:755-6Majeed FA, Voss S (1995). Performance indicators for general practice. British Medical Journal311:209-10Majeed FA, Lester H, Bindman AB (2007) Measuring Quality through Performance: Improving thequality of care with performance indicators. British Medical Journal 335: 916-8Maxwell R (1983) Seeking quality. Lancet 8314-5:45–8Medical Professionalism Project: ABIM Foundation (2002): Medical Professionalism in the NewMillennium: A Physician Charter. Annals of Internal Medicine 136:243-46Middleton E, Baker J (2003) Comparison of social distribution of immunisation with measles, mumps,and rubella vaccine, England, 1991-2001. British Medical Journal 326:854National Audit Office (2008) NHS Pay Modernisation: New Contracts for General Practice Services inEngland. The Stationary Office. <strong>London</strong>Roland M (2004). Linking physician pay to quality of care—a major experiment in the United Kingdom.New England Journal of Medicine 351:1448-54Rose G, Day S (1990). The population mean predicts the number of deviant individuals. British MedicalJournal 301:1031–34.Short K (2007) <strong>QOF</strong> vs NICE. British Journal of General Practice 57:748Starfield B (2001). New paradigms for quality in primary care. British Journal of General Practice51:303-9.Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Barros FC, Silva AC, Tomasi E (2000). Explaining trends in inequities: evidencefrom Brazilian child health studies. Lancet 356:1093-88

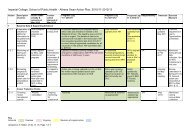

Summary of indicatorsHigher thresholds for existing Clinical <strong>QOF</strong> indicatorsPractices will receive a fixed number of <strong>QOF</strong>+ points for reaching or exceeding a revised upperthreshold for the indicators detailed below. Point awards will be in addition to those allocatedunder <strong>QOF</strong> and based on attainment at close of business on March 31 2010.<strong>QOF</strong><strong>QOF</strong>+IndicatorUpperThresholdThreshold& (Tolerance) †PointsASTHMA 6. The percentage of patients withasthma who have had an asthma review in theprevious 15mthsBP 5. The percentage of patients withhypertension in whom the last blood pressure(measured in the previous 9 months) is ≤150/90CHD 6. The percentage of patients withcoronary heart disease in whom the last bloodpressure reading (measured in the previous 15months) is ≤150/90CHD 8. The percentage of patients withcoronary heart disease whose last measuredtotal cholesterol (measured in the previous 15months) is ≤5mmol/lCHD 10. The percentage of patients withcoronary heart disease who are currentlytreated with a beta blocker (unless acontraindication or side-effects are recorded)CS 1. The percentage of patients aged from 25to 64 whose notes record that a cervical smearhas been performed in the last five yearsDM 12. The percentage of patients withdiabetes in whom the last blood pressure is≤145/8570% 95% (3%) 1070% 90% (2%) 2970% 98% (1%) 670% 87% (2%) 760% 87% (1%) 1480% 88% (7%) 3560% 86% (1%) 5Continues overleaf9

Continued…<strong>QOF</strong><strong>QOF</strong>+IndicatorUpperThresholdThreshold& (Tolerance) †PointsDM 17. The percentage of patients withdiabetes whose last measured total cholesterolwithin the previous 15 months is ≤5mmol/lDM 20. The percentage of patients withdiabetes in whom the last HBA1c is 7.5 or less inthe previous 15 monthsMH 6. The percentage of patients on theregister who have a comprehensive care plandocumented in the records agreed betweenindividuals, their family and/or carers asappropriateSTROKE 6. The percentage of patients with ahistory of TIA or stroke in whom the last bloodpressure reading (measured in the previous 15months) is ≤150/90 in the previous 15 monthsSTROKE 8. The percentage of patients with ahistory of TIA or stroke in whom the last totalcholesterol (measured in the previous 15months) is 5 mmol/l or less70% 88% (1%) 950% 77% (1%) 2050% 97% (1%) 370% 96% (1%) 660% 85% (1%) 5Under the current <strong>QOF</strong> 2009/10 proposal, DM20 will be replaced by DM23, which lowersthe target for HbA1c to ≤7.0. We recognise that attaining this more aggressive target willrequire significant effort involving potentially large numbers of patients. To rewardpractices as they progress towards the revised goal, we propose to retain DM20 within<strong>QOF</strong>+ until the end of March 2010. Since DM20 attainment status will no longer beavailable through QMAS, feedback will instead be provided through the same mechanismof monthly reporting used for the new <strong>QOF</strong>+ clinical indicators.† During consultation with practices concern was raised about the possibility, with an ‘allor-nothing’payment mechanism, of receiving no remuneration where the revised targetwas missed through accidental failures involving small numbers of patients. A range ofsolutions were considered to address this – including the use of payment ranges, similarto those of <strong>QOF</strong> – but all were felt to distract from a key aim of the revised targets, whichis to drive performance towards the best seen at a national level. It was decided to retainthe single upper threshold but to introduce a tolerance (bracketed figures in the tableabove) which lowers the threshold by the specified amount. Attainment lying at or abovethis lower figure will be remunerated by receiving half the available points. Where thepoint number is odd, the points will be divided unequally with the balance in favour ofthe tolerance payment. The existing 3-month exemption for newly registered patientswill be respected across these and the newly introduced indicators.10

New clinical <strong>QOF</strong>+ indicatorsNew indicators are distinguished from existing <strong>QOF</strong> targets by the plus (+) prefix. Blanketminimum attainment thresholds will no longer be included in year 1 of the <strong>QOF</strong>+ scheme (for more information see Appendix 2, Section A2.4). Point awards will be based on attainment atclose of business on November 30 2009.Cardiovascular disease prevention Chapter 3 (p19)Indicator<strong>QOF</strong>+pointsPaymentstages+ CVD PREVENT 1. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register whose notes have a Blood Pressurerecorded in the previous 17 months+ CVD PREVENT 2. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register whose notes have a record of BMImeasured in the previous 17 months+ CVD PREVENT 3. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register whose notes have a baseline record oftotal and HDL cholesterol recorded in the previous 17 months+ CVD PREVENT 4. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register for whom there is a record of a fastingblood glucose in the previous 17 months+ CVD PREVENT 5. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register whose notes have a record of familyhistory of CHD in first degree relatives (parents, brothers,sisters, or children of a patient)+ CVD PREVENT 6. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register whose notes have a record of familyhistory of diabetes in first degree relatives (parents, siblings,or children of a patient)+ CVD PREVENT 7. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register who have been offered lifestyle advice onexercise, and appropriate dietary changes within the previous17 months+ CVD PREVENT 8. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register who have been offered statin therapy (inline with 2008 NICE guidance on Lipid Modification) as part oftheir primary prevention management strategy8 40-90%8 40-90%8 40-90%8 40-90%8 40-90%8 40-90%10 40-90%10 40-90%It is prerequisite that in order to receive payment for + CVD PREVENT 1, practices have achievedthe existing <strong>QOF</strong> RECORDS 11 Indicator (The BP of patients aged 45 and over is recorded in thepreceding 5 years for at least 65% of patients.)11

Alcohol Chapter 4 (p27)Indicator<strong>QOF</strong>+pointsPaymentstages+ ALCOHOL 1. The percentage of patients on one or morepractice registers for CVD At-Risk, Diabetes, Stroke and TIA,Hypertension and CHD who have had AUDIT-C or FASTrecorded on the practice system within the previous 17months+ ALCOHOL 2. The proportion of patients who screen positiveusing either AUDIT-C or FAST within the previous 17 monthswho are subsequently recorded as having a brief interventionfor alcohol misuse15 20-70%30 40-90%It is prerequisite that in order to receive payment for + ALCOHOL 2, practices shall have reachedthe lower threshold for + ALCOHOL 1.Smoking Chapter 5 (p33)Indicator<strong>QOF</strong>+pointsPaymentstages+ SMOKING 1. The percentage of patients aged 15 years orolder whose notes record smoking status in the past 17months, or whose most recent recorded smoking status,recorded over the age of 25, indicates that they had neversmoked+ SMOKING 2. The percentage of patients aged 15 years orolder who smoke whose notes contain a record that smokingcessation advice or referral to a local smoking cessationservice has been offered within the previous 17 months20 40-90%10 40-90%Smoking in pregnancy Chapter 6 (p39)Indicator<strong>QOF</strong>+pointsPaymentstages+ SMOKING IN PREG 1. The percentage of pregnant womenwhose notes record their smoking status at the time of theirfirst booking appointment in primary care+ SMOKING IN PREG 2. The percentage of pregnant womenwho smoke whose notes contain a record that at the time oftheir first antenatal booking appointment in primary care theyhave been given smoking cessation advice and details of thelocal NHS Stop Smoking Services and the NHS pregnancysmoking helpline (0800 169 9 169)3 70-90%5 70-90%12

BreastfeedingIndicator+ BREASTFEEDING 1. The percentage of women who arerecorded as being pregnant on or after December 01 2008,and who at their antenatal booking appointment in primarycare have been given specific information on breastfeeding,including information on breastfeeding workshops+ BREASTFEEDING 2. The percentage of babies born on orafter December 01 2008 and breast fed at 6-8 weeks whoserecord indicates that breastfeeding support contact has beenoffered to the babies’ mother at the time of the 6-8 weekcheck+ BREASTFEEDING 3. At least 80% of babies born on or afterDecember 01 2008 have a record of feeding method at thetime of the 6-8 week check<strong>QOF</strong>+points Chapter 7 (p45)Paymentstages4 70-90%6 70-90%3 -EthnicityIndicator+ ETHNICITY 1. The percentage of patients on one or morepractice registers for: CVD At-Risk, Hypertension, CHD,Diabetes, Mental Health and Stroke and TIA whose notesrecord their ethnicity and first language+ ETHNICITY 2. The percentage of patients who have newlyregistered with the practice on or after December 01 2008whose notes record their ethnicity and first language<strong>QOF</strong>+points Chapter 8 (p51)Paymentstages30 60-90%20 90-100%13

RecordsIndicator+ PRESCRIPTION 1. The percentage of individual repeatmedications issued which have a diagnosis or symptom in theelectronic medical record relating to that medication+ REFERRALS 1. The percentage of outpatient referrals madeon or after December 01 2008 where both the referred-tospeciality and diagnosis/symptom triggering referral are codedon the clinical system+ CARERS 1. Carer status is recorded for 100% of individualsnewly registered on or after December 01 2008+ OSTEOARTHRITIS 1. The practice is able to produce aregister of patients who have osteoarthritis+ RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS 1. The practice is able to producea register of patients who have rheumatoid arthritis+ ECZEMA 1. The practice is able to produce a register ofpatients who have eczema+ PSORIASIS 1. The practice is able to produce a register ofpatients who have psoriasis<strong>QOF</strong>+points Chapter 9 (p57)Paymentstages45 40-90%50 70-90%6 -1 -1 -1 -1 -14

New non-clinical <strong>QOF</strong>+ indicatorsNew indicators are distinguished from existing <strong>QOF</strong> targets by the plus (+) prefix.New patient screening Chapter 10 (p65)Indicator+ PATIENT REGISTRATION 1. The practice is trained in and implements thePCT TB Early Referral Protocol to identify and refer patients who are newlyregistered at the Practice and who are new entrants to the UK fromcountries with a high TB prevalence<strong>QOF</strong>+points5Patient information Chapter 11 (p69)Indicator+ PATIENT INFORMATION 1. The practice uses the PCT practice informationleaflet template for patients which is designed to include information onthe following: Preventative services such as stop smoking, immunization andscreening Choice / Choose & Book PCT’s Patient Advice & Liaison Service and complaints team Walk-in and urgent care centres Practice opening times including extended hours Information for patients in a range of languages informing them oftheir right to interpreting services during appointments+ PATIENT INFORMATION 2. The practice takes responsibility for regularlyupdating practice information on the NHS choices website+ PATIENT INFORMATION 3. The practice has up to date patientinformation about local training and support for self-management (in theform of posters and leaflets) and that these are clearly displayed forpatients in waiting areas.<strong>QOF</strong>+points37315

Patient experience Chapter 12 (p77)Indicator+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 1. The practice takes part in a PCT-led local versionof the Picker Institute patient satisfaction survey+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 2. The practice takes part in a PCT-led feedbacksession based on the results of the local version of the Picker Institutepatient satisfaction survey and agrees an action plan including explicit andappropriate targets that can be used in the following 2 years to assess theextent to which the action plan is implemented+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 3. The practice shares with patients the results andaction plan from the local version of the Picker Institute patient satisfactionsurvey. This should be through information leaflets and poster(s) in thepractice’s waiting and reception area, and through the Practice’s PatientParticipation Group where this exists+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 4. The practice can show satisfactory objectiveevidence of implementing and achieving the action plan agreed with thePCT following the PCT-led feedback session based on the results of the localversion of the Picker Institute patient satisfaction survey. Deviations fromthe action plan must be described and explained+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 5. The practice has a register of patients who needsigning and interpreting support for appointments, including a record offirst language spoken+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 6. The practice offers double length appointmentsto patients identified as needing interpreting and signing support and to allpatients on the learning disabilities register+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 7. 100% of carers who are newly registered with thePractice on or after December 01 2008 have a record of being advised bythe Practice that they can ask Social Services for an assessment of their ownneeds+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 8. The practice has a system in place for taking thespecial needs of carers into account, including when allocatingappointments and issuing prescriptions+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 9. A named carer is recorded for at least 90% ofpatients on the learning disability register+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 10. The practice scores better than the nationalaverage on the local Picker survey response to the statement “I waitedmore than 2 working days for a GP appointment”+ PATIENT EXPERIENCE 11. The practice scores better than the nationalaverage on the local Picker survey response to the question “Have you hada problem getting through to your GP practice/health centre on thephone?”<strong>QOF</strong>+points35103057555202016

Patient safety Chapter 13 (p85)Indicator+ PATIENT SAFETY 1. The practice submits significant event analysis (SEA)summaries to an annual PCT audit+ PATIENT SAFETY 2. The practice can show evidence of reporting incidentsor near misses involving harm/potential harm to patients via the nationalreporting and learning system (NRLS) using the standard e-reporting form+ PATIENT SAFETY 3. The practice has a system for ensuring that all practicestaff have had CRB checks within the last three years+ PATIENT SAFETY 4. The practice has a system in place to assist, whereappropriate, with the multi-agency referral process for investigationsrelating to the protection of children and vulnerable adults, includingacknowledging any referrals or requests for information within 2 workingdays+ PATIENT SAFETY 5. The practice has a system in place for identifyingvulnerable children, and this includes cases where a parent is known to be asubstance misuser, has a severe mental health problem, or where there isdomestic violence+ PATIENT SAFETY 6. The case conference notes of all children who are thesubject of a Child Protection Plan are scanned into the child’s medicalrecords+ PATIENT SAFETY 7. The practice has a system in place for ensuring thatwhere a child has been the subject of a child protection plan, this isrecorded as a Significant Active problem in the records of the child, theparents and other members of the household, and that this leads toeffective flagging of records<strong>QOF</strong>+points445785517

C3<strong>QOF</strong>+ report on cardiovasculardisease preventionProposed indicatorsIndicator<strong>QOF</strong>+pointsPaymentstages+ CVD PREVENT 1. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register whose notes have a Blood Pressurerecorded in the previous 17 months+ CVD PREVENT 2. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register whose notes have a record of BMImeasured in the previous 17 months+ CVD PREVENT 3. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register whose notes have a baseline record oftotal and HDL cholesterol recorded in the previous 17 months+ CVD PREVENT 4. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register for whom there is a record of a fastingblood glucose in the previous 17 months+ CVD PREVENT 5. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register whose notes have a record of familyhistory of CHD in first degree relatives (parents, brothers,sisters, or children of a patient)+ CVD PREVENT 6. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register whose notes have a record of familyhistory of diabetes in first degree relatives (parents, siblings,or children of a patient)+ CVD PREVENT 7. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register who have been offered lifestyle advice onexercise, and appropriate dietary changes within the previous17 months+ CVD PREVENT 8. The percentage of patients on the PracticeCVD At-Risk Register who have been offered statin therapy (inline with 2008 NICE guidance on Lipid Modification) as part oftheir primary prevention management strategy8 40-90%8 40-90%8 40-90%8 40-90%8 40-90%8 40-90%10 40-90%10 40-90%The proposed indicators are in line with the recently published NICE Guidance on LipidModification (2008) and derived from NHS Hammersmith and Fulham’s LES on CVD PrimaryPrevention.19