N OCIETY' - the Society for Reproductive Biology

N OCIETY' - the Society for Reproductive Biology

N OCIETY' - the Society for Reproductive Biology

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

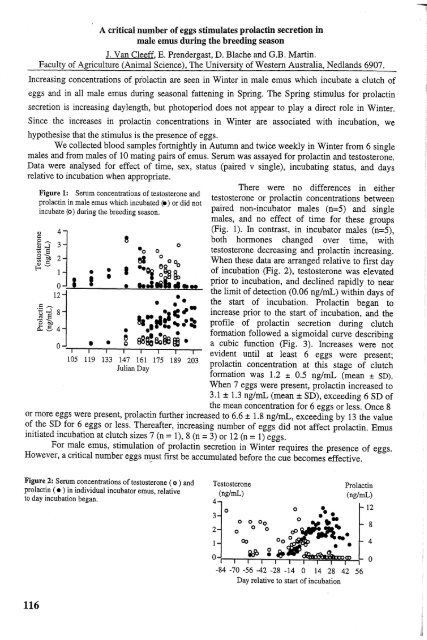

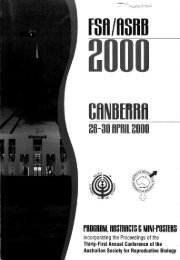

--o121:..- ....:l~ S 8o b.O~54oI•IA critical number ofeggs stimulates prolactin secretion inmale emus during <strong>the</strong> breeding seasonJ. Van eleeff, E. Prendergast, D. Blache and G.B. Martin.Faculty of Agriculture (Animal Science), The University of Westem Australia, Nedlands 6907.Increasing concentrations of prolactin are seen in Winter in male emus which incubate a clutch ofeggs and in all male emus during seasonal fattening in Spring. The Spring stimulus <strong>for</strong> prolactinsecretion is increasing daylength, but photoperiod does not appear to playa direct role in Winter.Since <strong>the</strong> increases in prolactin concentrations in Winter are associated with incubation, wehypo<strong>the</strong>sise that <strong>the</strong> stimulus is <strong>the</strong> presence of eggs.We collected blood samples <strong>for</strong>tnightly in Autumn and twice weekly in Winter from 6 singlemales and from males of 10 mating pairs of emus. Serum was assayed <strong>for</strong> prolactin and testosterone.Data were analysed <strong>for</strong> effect of time, sex, status (paired v single), incubating status, and daysrelative to incubation when appropriate.There were no differences in ei<strong>the</strong>rFigure 1: Serum concentrations of testosterone andtestosterone or prolactin concentrations betweenprolactin in male emus which incubated (.) or did notincubate (0) during <strong>the</strong> breeding season. paired non-incubator males (n=5) and singlemales, and no effect of time <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>se groups(Fig. 1). In contrast, in incubator males (n=5),•I••e• • o105 119 133 147 161 175 189 203Julian Dayoboth hormones changed over time, withtestosterone decreasing and prolactin increasing.When <strong>the</strong>se data are arranged relative to first dayof incubation (Fig. 2), testosterone was elevatedprior to incubation, and declined rapidly to near<strong>the</strong> limit of detection (0.06 ng/mL) within days of<strong>the</strong> start of incubation. Prolactin began toincrease prior to <strong>the</strong> start of incubation, and <strong>the</strong>profile of prolactin secretion during clutch<strong>for</strong>mation followed a sigmoidal curve describinga cubic function (Fig. 3). Increases were notevident until at least 6 eggs were present;prolactin concentration at this stage of clutch<strong>for</strong>mation was 1.2 ± 0.5 ng/mL (mean ± SD).When 7 eggs were present, prolactin increased to3.1 ± 1.3 ng/mL (mean ± SD), exceeding 6 SD of<strong>the</strong> mean concentration <strong>for</strong> 6 eggs or less. Once 8or more eggs were present, prolactin fur<strong>the</strong>r increased to 6.6 ± 1.8 ng/mL, exceeding by 13 <strong>the</strong> value?f. t?e SI? <strong>for</strong> 6.eggs or less. Thereafter, increasing number of eggs did not affect prolactin. EmusInItiated IncubatIon at clutch sizes 7 (n = 1), 8 (n = 3) or 12 (n = 1) eggs.For m~~ emus, stimulation of prolactin secretion in Winter requires <strong>the</strong> presence of eggs.However, a cntIcal number eggs m..ust fIrst ~e accumulated be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> cue becomes effective.Figure 2: Serum concentrations of testosterone ( 0 ) andprolactin (. ) in individual incubator emus, relativeto day incubation began.Testosterone(nglmL)4o 0 ••~ oo~ooooo oo~Jt""".• •Prolactin(ng/mL)o ~ i ~ ~'rrsr'Ofiii i-84 -70 -56 -42 -28 -14 0 14 28 42 56Day relative to start of incubation1284oEffects of levonorgestrel on fertility in <strong>the</strong> tammar wallaby, Macropus eugenii.C. Nave, G. Shaw, R.V. Short, and M.B. RenfreeDepartment of Zoology, Melbourne University, Parkville 3052. Australia.INTRODUCTIONLevonorgestrel is a syn<strong>the</strong>tic progestin, which provideseffective contraception in women. It has several modesof action but primarily it inhibits <strong>the</strong> hypothalamicpituitaryaxis, which in turn prevents ovulation.Macropodid marsupials are highly fecund, so <strong>the</strong>irnumbers are capable of increasing rapidly, causingconsiderable management problems in public parks andwildlife sanctuaries. In <strong>the</strong>se semi-urban areas alternatemanagement techniques to culling and baiting aredesirable.The aims of this study are to test <strong>the</strong> efficacy oflevonorgestrel as a possible anti-fertility agent <strong>for</strong>macropodid marsupials, using tammar wallabies as amodel species.MATERIALS AND METHODSFemale tammar wallabies carrying pouch young (n=12)received a single - levonorgestrel implant (Leiras,Finland). Implants composed of thin-walled siliconetubing, sealed at each end with silastic adhesive were2.5mm in diameter, 4.3cm in length and contained75mg of levonorgestrel. Control implants consisting ofa hollow silicone tubing of <strong>the</strong> same length anddiameter as <strong>the</strong> levonorgestrel implants were placed infemale tammar wallabies carrying pouch young (n=12).Implants were inserted subcutaneously into <strong>the</strong> medialsubdermal connective tissue, between <strong>the</strong> shoulderblades. Pouch young were removed (RPY) 3 days afterinsertion, and <strong>the</strong> adult females given bromocriptine(25mg)(im) to synchronize reactivation of <strong>the</strong>irdiapausing blastocysts and initiate <strong>the</strong> 1 st cycle.Wallabies were checked daily 25-31 days followingpouch young removal, <strong>for</strong> birth and/or a mating plug.The new pouch young were removed 3-5 days postpartumto initiate <strong>the</strong> second cycle and bromocriptinewas given again to <strong>the</strong> adult females (25mg) (im).Blood samples (5m1) were collected from <strong>the</strong> lateral tailvein at specific times throughout pregnancy from 4levonorgestrel and 4 control implanted tammars.Plasma progesterone was measured using aradioimmunoassay validated <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> tammar.Levonorgestrel implants were removed from anadditional 6 tammar wallabies one-month after <strong>the</strong>initial implantation during <strong>the</strong> seasonal quiescenceperiod, reproduction in <strong>the</strong>se animals was monitored <strong>for</strong><strong>the</strong> subsequent 9 months.RESULTSEleven of <strong>the</strong> twelve control implanted tammars gavebirth at <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> frrst cycle and eight of <strong>the</strong>seanimals gave birth at <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> second cycle (table1).~ 20e~~ 15e c-o~ 10Il..50Table 1: Birth in <strong>the</strong> tammar after treatment withcontrol or levonorgestrel implant.Control Levonorgestrel1 st Cycle 11/12 9/112 nd Cycle 8/11 0/8Nine of <strong>the</strong> twelve levonorgestrel treated animals gavebirth during <strong>the</strong> first pregnancy cycle, but none gavebirth at <strong>the</strong> end of<strong>the</strong> second pregnancy cycle (table 1).Birth was observed in 4 out of <strong>the</strong> 6 tammars that hadlevonorgestrel implants removed at <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong>breeding season.Radioimmunoassay of progesterone showed nosignificant difference in circulating levels duringpregnancy <strong>for</strong> both control and experimental tammars(fig. 1).o--- Control-+-Levonorgestret5 10 15 20 25Days since pouch young removal30Fig 1: Plasma progesterone levels throughoutpregnancy in one control and one levonorgestrel treatedtammar.DISCUSSIONLevonorgestrel does not interfere with a pregnancyfollowing diapause in <strong>the</strong> tammar. Normal progesteronelevels were observed throughout pregnancy inlevonorgestrel treated animals. Levonorgestrelsuccessfully inhibits conception at <strong>the</strong> post-partumoestrus in <strong>the</strong> tammar wallaby. The lack of a postpartummating at <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> frrst cycle inexperimental tammars suggests that levonorgestrel issuppressing ovulation, but this is still to be confirmed.The contraceptive effects of levonorgestrel arereversible in <strong>the</strong> tammar upon implant removal.Levonorgestrel could provide an alternative method <strong>for</strong>population control of o<strong>the</strong>r macropodid marsupials, like<strong>the</strong> eastern grey kangaroo, Macropus giganteus, insmall, selected wildlife parks and sanctuaries.116 117