Using Illness Scripts to Teach Clinical Reasoning Skills to ... - STFM

Using Illness Scripts to Teach Clinical Reasoning Skills to ... - STFM

Using Illness Scripts to Teach Clinical Reasoning Skills to ... - STFM

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Vol. 42, No. 4255Medical Student Education<strong>Using</strong> <strong>Illness</strong> <strong>Scripts</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Teach</strong> <strong>Clinical</strong> <strong>Reasoning</strong><strong>Skills</strong> <strong>to</strong> Medical StudentsAnna Lee, PhD; Gavin M. Joynt, MB, BCh; Alex K.T. Lee, MPhil;Anthony M.H. Ho, MD; Michele Groves, PhD; Alexander C. Vlantis, MB, BCh;Ronald C.W. Ma, MB, BChir; Colman S.C. Fung, MB,BS; Cindy S.T. Aun, MDBackground and Objectives: Most medical students learn clinical reasoning skills informally duringclinical rotations that have varying quality of supervision. We conducted a randomized controlledtrial <strong>to</strong> determine if a workshop that uses “illness scripts” could improve students’ clinical reasoningskills when making diagnoses of patients portrayed in written scenarios. Methods: In 2007–2008,53 fourth-year medical students were randomly assigned <strong>to</strong> either a family medicine (intervention)or psychiatry (control) clerkship at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Students in the interventiongroup participated in a 3-hour workshop on clinical reasoning that used illness scripts. Theworkshop was conducted with small-group teaching using a Web-based set of clinical reasoningproblems, individualized feedback, and demonstration of tu<strong>to</strong>rs’ reasoning aloud. The effectivenessof the intervention was assessed using the Diagnostic Thinking Inven<strong>to</strong>ry (DTI) and the measuremen<strong>to</strong>f individual students’ performance in solving clinical reasoning problems (CRP). Results: The postinterventionoverall DTI scores between groups were similar (mean difference 0, 95% confidenceinterval [CI]= -7.4 <strong>to</strong> 7.4). However, the <strong>to</strong>tal scores on the CRP assessment were 14% (95% CI=8%<strong>to</strong> 21%) higher in the intervention group than in controls. Conclusion: A workshop on illness scriptsmay have some benefit for improving diagnostic performance in clinical reasoning problems.(Fam Med 2010;42(4):255-61.)The ability <strong>to</strong> diagnose effectively and accuratelyrequires an appropriate clinical knowledge and soundclinical reasoning skills. Medical educa<strong>to</strong>rs agree thatclinical reasoning is a central component of physiciancompetence. 1 Currently, most students learn clinicalreasoning skills informally in clinical rotations withvarying quality of supervision.When making a diagnosis, students often reason byan iterative process of hypothesis generation and testingof one symp<strong>to</strong>m at a time. 2 Since they may be unable <strong>to</strong>synthesize clinical features in<strong>to</strong> meaningful clusters orsyndromes, their clinical reasoning styles are typicallycharacterized by poorly organized knowledge structure.In comparison, expert clinicians reason by organizingFrom the Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care (Dr Lee, Dr Joynt,Mr Lee, Dr Ho, Dr Aun), Department of O<strong>to</strong>rhinolaryngology, Head andNeck Surgery (Dr Vlantis), Department of Medicine and Therapeutics (DrMa), School of Public Health and Primary Care (Dr Fung), The ChineseUniversity of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong,China; and Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane,Queensland, Australia (Dr Groves).and prioritizing syndrome recognition through comparingand contrasting key clinical features in makinga diagnosis (“illness scripts”). 2 The illness scriptconcept 3 provides a theoretical framework <strong>to</strong> explainhow medical diagnostic knowledge can be organizedfor diagnostic problem solving.<strong>Illness</strong> scripts are a product of extensive experiencewith patients superimposed on a formal knowledgestructure. 4 Expert clinicians use illness scripts mos<strong>to</strong>f the time in their clinical reasoning since it involvesa knowledge-driven model of pattern recognition thatmay be more efficient than hypothetico-deductivereasoning used by students. 5The Chinese University of Hong Kong undergraduatemedical curriculum is a body-system-based modeltaught over 5 years. In response <strong>to</strong> faculty members’perception that our students had poor clinical reasoningskills when starting clinical rotations during their fifthand final year of medical school, we constructed a brief3-hour educational intervention <strong>to</strong> improve those skills.Our hypothesis was that an educational interventionwould promote and improve students’ competency in

256 April 2010 Family Medicineclinical reasoning in a systematic manner. The objectiveof our study was <strong>to</strong> determine if a brief workshop<strong>to</strong> teach students <strong>to</strong> refine their knowledge organizationthrough the use of illness scripts could improvestudents’ clinical reasoning skills for diagnosis.MethodsThe workshop started with a 20-minute lecture <strong>to</strong> allstudents. It introduced the key elements of the clinicaldiagnostic process. 6 This was followed by a 1-1/4 hoursmall-group tu<strong>to</strong>rial on problem representation and developingan illness script and a final tu<strong>to</strong>rial, also 1-1/4hours long, in the computing labora<strong>to</strong>ry on developingand selecting an appropriate illness script. A manualfor teachers wishing <strong>to</strong> conduct a similar workshop isavailable from the authors by request.Problem Representation and Developingan <strong>Illness</strong> ScriptThe objective in the workshop was for students <strong>to</strong>acquire the skill of articulating the patient’s problemand <strong>to</strong> develop an illness script based on two clinicalscenario articles from the New England Journalof Medicine’s <strong>Clinical</strong> Problem-solving series. 7,8 Thepurpose was <strong>to</strong> help students develop a succinct andcoherent case presentation from the clinical problempresented in the journal article and <strong>to</strong> organize pertinentclinical data in<strong>to</strong> a structured template (illness script) <strong>to</strong>formulate the basis of reaching a diagnosis. We chosethe articles based on the complexity of the scenario andthe perceived interest <strong>to</strong> students.A PowerPoint presentation of the clinical scenarioswas prepared by one faculty member before the workshop.Three other physicians from the Faculty of Medicineacted as tu<strong>to</strong>rs for the interactive sessions.The students were given the details of the clinicalpresentation, his<strong>to</strong>ry, and examination results duringthe workshop. The tu<strong>to</strong>r’s task was <strong>to</strong> guide the students<strong>to</strong> identify the important findings and <strong>to</strong> help themdevelop a presentation of the patients’ problems usingthe teaching strategies described by Bowen. 6 Studentswere expected <strong>to</strong> characterize the clinical problempresented in the two articles as “an elderly man with apersistent cough” 7 and “a middle-aged woman with anacute swollen and painful left leg.” 8The tu<strong>to</strong>r then reasoned aloud <strong>to</strong> compare and contrasthis expert problem representation with those ofthe students. Students then developed an illness scriptby listing the enabling (predisposing conditions or riskfac<strong>to</strong>rs), fault (pathophysiological insult), and clinicalconsequences (key signs, symp<strong>to</strong>ms, complaints) withfeedback from the tu<strong>to</strong>r. A sample problem illnessscript for pertussis in “an elderly man with a persistentcough” 7 is shown in Appendix 1.Developing and Selecting an Appropriate<strong>Illness</strong> ScriptThe objective of this session was for students <strong>to</strong>acquire the skill of developing and selecting an appropriateillness script in formulating the most probablediagnosis for a given clinical problem. The purposewas <strong>to</strong> help students prioritize multiple diagnoses byidentifying discriminating features for each diagnosticconsideration. We developed a Web-based program thatwas comprised of a set of 20 clinical reasoning problems(CRPs) for teaching, combined with a scoring systemfor assessment. Our Web-based program was based onpreviously validated paper-based CRPs developed byGroves et al in conjunction with 22 family medicinephysicians at the University of Queensland. 9 Details ofthe scoring system for CRP are described elsewhere. 9The reliability of the paper-based CRP for medicalstudents ranged from 0.61 <strong>to</strong> 0.83. 9Prior <strong>to</strong> the implementation of the workshop, wetested the Web-based program on eight final-year studentswho were not involved in the study, <strong>to</strong> identifycomputing errors in the program and scoring system.The Web-based CRPs for post-workshop assessmenthad acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=0.80).For each CRP, students had <strong>to</strong> nominate the two mostlikely diagnoses, list the clinical features that supportedor opposed each diagnosis, and weigh each of the clinicalfeatures (slightly relevant, somewhat relevant, veryrelevant) from a series of drop-down menus. For thefirst CRP, two tu<strong>to</strong>rs interacted with students by askingthem <strong>to</strong> list all important findings from the case, createa problem representation based on those findings,generate and prioritize diagnostic considerations thatidentify discriminating features for each consideration,identify findings from the case <strong>to</strong> support the diagnosis,and lastly <strong>to</strong> identify and compare alternative diagnoses.6 Students were assisted if necessary at each step<strong>to</strong> reach reasonable conclusions and, when appropriate,positive feedback for correct responses was provided.This was then supplemented by a tu<strong>to</strong>r reasoning aloud<strong>to</strong> summarize the process and illustrate key componentssuch as the relevance of supporting clinical featuresassociated with the correct diagnoses.Students were encouraged <strong>to</strong> gradually work onfour other CRPs individually during the session, withindividual feedback from the tu<strong>to</strong>rs as they reasonedaloud. Thus, students were developing their own illnessscripts for each CRP attempted. At the end of eachcompleted CRP, the student was given an au<strong>to</strong>matedscore by the program that gave immediate quantitativefeedback on their clinical reasoning skills. Toward theend of the session, the tu<strong>to</strong>rs reasoned aloud for theselected CRPs <strong>to</strong> illustrate the gap between actual anddesired expert performance. A sample CRP is shownin Appendix 2. The overall score for CRPs from theresponses shown in the tables was 28/37, as visceral

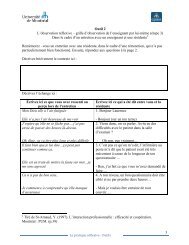

260 April 2010 Family MedicineConclusionsThe key elements in the intervention involved theuse of integrated small-group teaching, individual feedback<strong>to</strong> students when developing appropriate illnessscripts, highly motivated tu<strong>to</strong>rs who reasoned aloud <strong>to</strong>students <strong>to</strong> highlight the desired performance, and thedevelopment of a Web-based set of clinical reasoningproblems for teaching and assessments. Our initialresults are encouraging. They can serve as a rationalefor implementation of a one-morning clinical reasoningmodule <strong>to</strong> improving clinical diagnostic skills ofmedical students.Acknowledgments: The work described in this paper is supported by a grantfrom the University Grants Committee <strong>Teach</strong>ing Development TrienniumGrant of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (ProjectNo. 4170255).This work was presented at The Chinese University of Hong Kong,Faculty of Medicine Curriculum Day meeting in September 2008 in HongKong.Corresponding Author: Address correspondence <strong>to</strong> Dr Lee, The ChineseUniversity of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Department of Anaesthesiaand Intensive Care, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong, China. +852-2632-2735.Fax: +852-2637-2422. annalee@cuhk.edu.hk.Re f e r e n c e s1. Norman G. Research in clinical reasoning: past his<strong>to</strong>ry and currenttrends. Med Educ 2005;39(4):418-27.2. Schmidt HG, Norman GR, Boshuizen HP. A cognitive perspectiveon medical expertise: theory and implication. Acad Med1990;65(10):611-21.3. Barrows HS, Fel<strong>to</strong>vich PJ. The clinical reasoning process. Med Educ1987;21(2):86-91.4. Norman G. Building on experience—the development of clinical reasoning.N Engl J Med 2006;355(21):2251-2.5. Charlin B, Tardif J, Boshuizen HP. <strong>Scripts</strong> and medical diagnosticknowledge: theory and applications for clinical reasoning instructionand research. Acad Med 2000;75(2):182-90.6. Bowen JL. Educational strategies <strong>to</strong> promote clinical diagnostic reasoning.N Engl J Med 2006;355(21):2217-25.7. Cornia PB, Lipsky BA, Saint S, Gonzales R. <strong>Clinical</strong> problem-solving.Nothing <strong>to</strong> cough at—a 73-year-old man presented <strong>to</strong> the emergencydepartment with a 4-day his<strong>to</strong>ry of nonproductive cough that worsenedat night. N Engl J Med 2007;357(14):1432-7.8. Fazel R, Froehlich JB, Williams DM, Saint S, Nallamothu BK. <strong>Clinical</strong>problem-solving. A sinister development—a 35-year-old woman presented<strong>to</strong> the emergency department with a 2-day his<strong>to</strong>ry of progressiveswelling and pain in her left leg, without antecedent trauma. N Engl JMed 2007;357(1):53-9.9. Groves M, Scott I, Alexander H. Assessing clinical reasoning: amethod <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r its development in a PBL curriculum. Med <strong>Teach</strong>2002;24(5):507-15.10. Bordage G, Grant J, Marsden P. Quantitative assessment of diagnosticability. Med Educ 1990;24(5):413-25.11. Beullens J, Struyf E, Van DB. Diagnostic ability in relation <strong>to</strong> clinicalseminars and extended matching questions examinations. Med Educ2006;40(12):1173-9.Appendix 1Sample Problem <strong>Illness</strong> Script for Pertussis in “An Elderly Man With a Persistent Cough” 7 ** The illness script forms the logical construct underlying the symp<strong>to</strong>ms and signs making up the recognizable patterns for making a diagnosis.

Medical Student EducationVol. 42, No. 4261Appendix 2Sample <strong>Clinical</strong> <strong>Reasoning</strong> Problem From the Web-based Program