quadrangle - Emory College - Emory University

quadrangle - Emory College - Emory University

quadrangle - Emory College - Emory University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

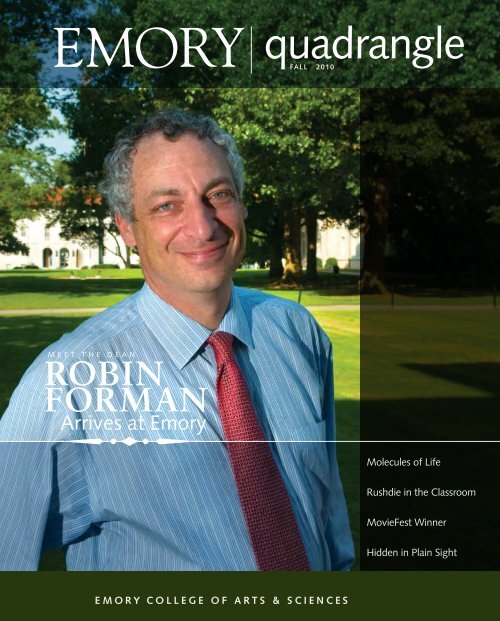

<strong>quadrangle</strong>fall 2010m e e t t h e d e a nr o b i nf o r m a nArrives at <strong>Emory</strong>Molecules of LifeRushdie in the ClassroomMovieFest WinnerHidden in Plain Sighte mor y college of arts & sciences

FeaturesHow Much Is That Molecule in the Window? 8–11<strong>Emory</strong> researchers in biology and chemistry push(and police) the boundaries of synthetic lifeOut of the Archive, Into the ClassroomSalman Rushdie on teaching, film, and saving his notes 12–15departments2-5 ProfilesRobin Forman provides new leadership in the<strong>College</strong>; Student filmmakers take Vegas—nextstop L.A.6-7 Q CornersLook closely: this trail is on campus but off the radarp a g e 4p a g e 6p a g e 216-17 Eagle Eye18-19 BookmarksMatthew Bernstein investigates the film and TVlegacy of a sensational murder trial; morefaculty books20-24 KudosDelores Aldridge and the rewards of sociology;more faculty accomplishments25-28 ImpactThe gift of travel; new <strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong> AlumniBoard membersp a g e 8p a g e 12Editor: d a v i d r a n e yArt Director: s t a n i s k o d m a nLead Photographer: k a y h i n t o nProduction Manager: s t u a r t t u r n e rContributing Writers: h a l j a c o b sm a r c s c h u l t zt i f f a n y w o r b o yContributing Photographers: a n n b o r d e nj o e b o r i sb r y a n m e l t zj o n r o ub re t t w e i n s t e i n

n e w d e a n i n t o w nr o b i n f o r m a n Arrives at <strong>Emory</strong>If <strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong>’s new dean were to fill out a Facebookprofile, he’d certainly include something about math—especially topology and combinatorial methods, his specialty—and about serving as Rice <strong>University</strong>’s dean of undergraduates. Hemight also save space for baseball, chess and stand-up comedy.Robin Forman accepted the position of dean of the <strong>College</strong>of Arts and Sciences this summer after a nationwide search.A professor and chair of math at Rice, he will also hold the AsaGriggs Candler Professorship in Mathematics.Dabbling in stand-up no doubt served Forman well inoverseeing both the academic and the social sides of Rice undergraduatelife. And a sense of humor couldn’t hurt in his new role.At <strong>Emory</strong> his responsibilities include strategic, academic andfinancial planning for nearly fifty departments and programs, aswell as promotion and tenure decisions.Chess, like comedy, is a longtime hobby. “I don’t get thechance to play in clubs or tournaments any longer,” Formansays, “but I still enjoy studying the game, keeping up with theprogress of the top grandmasters, and I’ll occasionally headto a chess website for a quick game over the Internet.” Whenhe’s at home, the dean also enjoys reading, with tastes that runtoward “literary fiction, with the occasional spy novel thrownin. But I’ve recently found myself drawn more to nonfiction.”And baseball? That’s a family affair. Dean Forman is joinedin Atlanta by his wife and son, Saul, age 13. “Saul is passionateabout baseball,” he says, “both as a fan and a player, andAnn and I have enthusiastically joined him on his journey. Weenjoy watching baseball at all levels—youth, college, minor andmajor leagues—and all our recent family vacations have beenbaseball-themed. Of course my most joyful and most stressfulbaseball moments involve watching Saul play. When we’re notcheering on his teams, we can often be found exploring the wonderfulrestaurant options in Atlanta. We’ve already learned thatthis is a great city for anyone who appreciates food.”No one who knows Forman will be surprised that he places astrong emphasis on the student experience at <strong>Emory</strong>. He servedas master of a residential college at Rice, and he remembers hisown undergraduate experience as “a thrilling intellectual journey,and great fun. I made some wonderful life-long friends,among both students and faculty. I also took full advantage ofthe opportunities to participate in extra-curricular activities:I played intramural sports, played in rock and roll bands, and,of course, joined the chess club.”At <strong>Emory</strong>, says Forman, “The aim of our undergraduateprogram is to take in high school students and graduate youngadults. This requires that they develop in many ways beyond theintellectual growth that forms the core of the <strong>College</strong> experience.We have to make use of the entire campus. I look forward toworking with the Campus Life team to create a student experience,in the classroom and out, that helps our remarkable studentsachieve their potential.”An important part of this, he says, is community service.“There’s a great passion for community service among thestudents here, and a wonderful collection of opportunitiesavailable to them—especially through the Office of <strong>University</strong>-Community Partnerships and Volunteer <strong>Emory</strong>. Our goal shouldbe to continually support opportunities that provide both benefitfor the community and educational value for our students.”Faculty play a crucial role in Forman’s view of a thriving<strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong>. As a veteran teacher and scholar, he calls thedual mission of teaching and research “one of the definingfeatures of the <strong>College</strong>,” adding, “I have had numerous opportunitiesto chat with <strong>Emory</strong> faculty, and many of them spoke oftheir passionate commitment to this ideal. Many in fact cameto <strong>Emory</strong> precisely because they believe in that mission. Andit’s been a wonderful experience to walk down the halls of thedepartments and see the spectacular work that’s taking placein every building on campus.“The university is at its best when these aspects overlap—when students have the opportunity to learn by participating inour research mission. The <strong>College</strong> does this very well,” he says.Forman notes too that he has been impressed by all the “ambitiousand creative approaches to interdisciplinary work” at <strong>Emory</strong>.Asked to pick the most pressing issue facing higher educationtoday, he answers, “The financial crisis. We had allgotten used to continuous expansion, and this was especiallytrue at <strong>Emory</strong>, which experienced three decades of quite dramaticgrowth. This was mission-driven growth, with excitingnew opportunities for scholarship and student programs. Butthe last two years required a pause, and even a slight contraction.The positive side is that it has given us a chance to regroup, andto build in new efficiencies.”Other effects of the recession ought to be resisted, Formansays. “In times of financial stress, there can be a tendency to lookat higher education in purely vocational terms. It becomes evenmore important to educate students, parents, employers, politicalleaders, and others about the value of a liberal arts education, therole it plays in preparing our students to be successful adults. I’mnot speaking just of professional success, but of success as happy,healthy, fulfilled adults.”“Our goal should be to continuallysupport opportunities that provideboth benefit for the community andeducational value for our students.”2 fall 2010 fall 2010 3

Unbeaten PathIt’s easy to miss. You’re headed for the <strong>College</strong> onAsbury Circle, the business school at your back andWoodruff Library towering on your left; you treadthe sidewalk thinking about work or classes or theweekend. Unless you glance to your left as youpass a grove of trees briefly obscuring the library,you won’t see the gap. Look, and you’ll spycraggy stone steps leading down toward asemi-lit space that’s half <strong>Emory</strong>, half older.Gary Hauk calls it “the grotto.” The vice president and deputy tothe president has been a member of the <strong>Emory</strong> community foryears, but even among longtime <strong>Emory</strong> staffers he’s in the minorityfor knowing this place. An informal, completely unscientific surveysuggests that most people on campus have no idea it’s there.Step through the gap and you descend toward Nettie’s Creek,which burbles out of one stone culvert and into another, disappearingunder the Center for Library and Information Resources(CLAIR), the Woodruff addition built in 1996-98. Sunlight filtersthrough the canopy and reflects off the windows of Jazzman’sCafé on the first floor. But even a distracted student in search ofdiversion at the café would be hard pressed to make out the walkwayfrom his seat.<strong>University</strong> architect Jen Fabrick knows the grotto. She arrived at<strong>Emory</strong> in early 1998 as the library addition was being completed,and remembers the ravine then as recently graded and planted.“I never did find out who laid out the path, but I’ve enjoyed itsoffered moments of peace at various times over the years. I’d beinterested to know.”Before 1996 there was a pedestrian bridge on this spot, spanningthe creek from one corner of the <strong>quadrangle</strong> to the libraryplaza entrance. Charles Forrest, Woodruff facilities director and projectmanager for CLAIR, says the path was “intended to be an amenityfor the community, to provide access to the remnant ravine onthe upstream side of the addition.” Though the new constructionbisected the ravine, Nettie’s Creek flowed on, as water will, fromthis upstream portion—now Asbury Ravine—beneath the libraryand into Baker Woodlands, passing under Mizell Bridge behind theCarlos Museum (see “Place Apart,” Spring 2006).by David RaneyThe walkway and plantings were an effort,says Hauk, to alleviate “some consternation” aboutthe construction “intruding into the greenery of thatpart of the ravine.” Forrest confirms this recollection. Tominimize the environmental impact on the green spacespanned by the pedestrian bridge, he says, “the projectteam committed resources to restore the area with nativeplantings appropriate for a piedmont ravine.”To do this, landscape architects conducted a pre-constructioninventory of species in the ravine, matched this to a list ofplants associated with piedmont forests, then planted accordingly.Today more than sixty species thrive here, including roughlyfifteen canopy or understory trees and dozens of flower, shrub,and herbaceous varieties.Let your eyes adjust, and look around. Familiar leaves of oak,maple, laurel and holly mix with a profusion of others with lesscommon names: doll’s eyes, trumpet flower, spangle grass, snowdroptree. Others are more fanciful still. Arrive armed with a plantguide and you might find dog hobble, cranesbill, wood vamp,creeping lilyturf, and the barely credible “heartleaf foamflower.”The path has no official name. Librarian Tim Bryson calls it “thetrail” and provides helpful information on its planning and design,as well as on subsequent plant inventories and tours. ChristopherBeck knows it too, though he wasn’t yet at <strong>Emory</strong> in 1998.A senior lecturer in biology, Beck was chair of the Committeeon the Environment from 2006-09 and considers the ravine planan upgrade. “My understanding is that the area the path cutsthrough was covered in English ivy at one point, and volunteersfrom the library removed it and native plants were restored to thearea.” Those ivy pulls continue periodically.Keep walking past more greenery and stacked stone, and witha few last steps you emerge on a cobbled terrace, a few feet fromthe statue of Robert Woodruff near the library’s entrance. Be preparedto startle anyone sitting on the benches there. Odds are theydon’t know the path exists; you might as well have walked out ofa wall.If landscaping, stonework, and a drop in noise and temperaturearen’t appealing enough, you’re also likely to be escorted on yourvisit by chipmunks rustling in the foliage and mockingbirds overhead.There’s plenty to see here, without looking all that hard.6 fall 2010

How Much Is That Molecule in the Window?The Science and Ethics of CreatingSynthetic Molecules by Hal Jacobsillustration by Mark McGinnisIn May, genetic pioneer and entrepreneur Craig Venter made headlines worldwide when he proclaimed(most scientists report, Venter proclaims) the existence of the “first self-replicating cellwe’ve had on the planet whose parent is a computer.”It’s “a new era in biology,” wrote the Wall Street Journal. “This invention and others like it in thefield of synthetic life could rival or surpass the invention of the internal combustion engine, or themicrochip,” said Fortune.A bioethicist in Nature said the discovery was “likely to prove asmomentous to our view of ourselves and our place in the universe asthe discoveries of Galileo, Copernicus, Darwin, and Einstein.”As a result of the attention, President Obama asked thePresidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, with<strong>Emory</strong> President James Wagner as vice chair, to focus on syntheticbiology. Among the first experts to speak at a commission hearingwas Paul Wolpe, director of the <strong>Emory</strong> Center for Ethics, who delivereda thoughtful talk on science, religion and the ways they informone another.It’s only fitting that <strong>Emory</strong> have a seat at the table for such animportant conversation.Chemists and biologists here are recognized nationally fortheir research and work with students. Informed by collaborationswith ethicists, social scientists, artists and others, <strong>Emory</strong> scientistsare at the forefront of a field that is rapidly making advances intouncharted territory.Not Your Grandfather’s MoleculesFrom where David Lynn sits, Venter’s discovery was more of a technologicalfeat than a major turning point in history. “The presspicked it up because it involved synthetic life,” says Lynn, AsaGriggs Candler Professor of Chemistry and Biology.“But scientists have been moving genes from one organism toanother for decades. What Venter did was make a whole genome,with all the components and all the information, and then moveit into an existing bacterium.” Lynn smiles. “It was a testosteronebasedshow of technology.”Because of the discovery and the work that Lynn and others aredoing, however, we can expect to see the pace of evolution accelerate.What might have taken thousands of years to change in theecosystem may take months in the laboratory.Lynn’s research group looks at the mechanics of how life works:the structures and forces that enable molecules to assemble, andhow chemical information can be stored and translated into newmolecular entities. His lab is one of fifteen sharing a $20 milliongrant from the National Science Foundation and the NationalAeronautics and Space Administration to see how the forces ofevolution can be harnessed to new structures and functions.Lynn collaborates with other leading researchers at <strong>Emory</strong>like Ichiro Matsuma, associate professor of biochemistry,whose group applies the new tools of synthetic biology tolongstanding questions about how complex systems such asproteins and cells originate and evolve.Thousands of years ago, humans selectively bred horses anddogs in order to benefit from certain traits they found useful.8 spring fall 2010fall 2010 9

Out of the ArchiveInto the ClassroomSalman Rushdie at <strong>Emory</strong>Bestselling author and Booker Prize winner Salman Rushdie teaches at<strong>Emory</strong> each spring as the <strong>Emory</strong> Distinguished Writer in Residence. Hispapers became part of <strong>Emory</strong>’s Manuscript, Archives & Rare Book Library(MARBL) in 2007. He spoke about both with editor David Raney in March.Did you expect at some point to be asked foryour collected papers?No, I had truthfully never given a day’s thought to having thiswork [archived], and certainly not in my lifetime. I must havethought about it a bit, because I didn’t throw everything away.But the idea that I would do it while I was still a functioningindividual just had never crossed my mind.And of course collecting and note-taking aren’tthe same thing—you can be something of apackrat, without thinking of archives.No, it’s not the same thing. And certainly, I must say, even atthe point at which I agreed to do it, it still didn’t occur to methat there’d be an exhibition. It’d be an archive, and if peoplewanted to study stuff, they could come and study it in a kind ofbook-stack private way. Never occurred to me that it would beunder glass.I don’t know which would be more alarming tome, my own scribblings writ large, or my faceat six by six feet.Well the thing is, I’m used to seeing my face—the face doesn’tbother me—but I’m not used to seeing my scribblings. Theseother things were never supposed to be seen by anyone. Ofcourse what is even odder is that I have virtually no memoryof them.As you said at the archive’s opening, theywere “things on the way to other things.”You don’t remember your notes. In the Times article today, thejournalist quotes some passage and I have absolutely no memoryof writing that. People could tell me I said anything.I want to talk about teaching a bit. I saw youand Vice President Rosemary Magee talkingabout it during a “Creativity and the Arts”event a couple of years ago.That was very enjoyable.She asked you about teaching and what rulesyou had, and you said something along thelines of “Abandon all theory, ye who enterhere.”Well that’s the thing that I feel has happened in the teaching ofliterature, that a kind of pseudo-science of critical theory hasbeen imposed upon it. And it gets away from why people readbooks. We read books for joy. The old-fashioned idea of closereading is much closer to that. Really it’s just me saying there’sno point in my pretending to be a literature professor in theordinary way, because it’s not my training. And what I bring tothe reading of books has to do with the practice of writing andhow that makes me think about what other people do.Are the students surprised by this?Either they’ve gotten more used to me, or they’ve heard whatit’s like from each other, because the first year I did it, there wasa sort of genuine shock when I said that they ought to parktheir theory at the door. Then there was a sort of unburdening,and they seemed to enjoy it. The last couple of years that senseof shock hasn’t been there. So I think they’ve heard from otherpeople coming in that it’s going to be like this.Are you teaching graduate students as well asundergraduates?It’s been some of both. Contemporary World Literature is sortof a grand title for the seminars. And so far I’ve not repeatedmyself. The first year I took modern classic novels, includingGünter Grass and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and taught those.Last year I tried something that was so successful I think I mightdo it again next year, which was to talk about turning booksinto film. The conventional wisdom is that films are less goodthan the masterpieces they’re based on. And often very greatfilms are made out of second-rate books. But what I wanted tolook at was the phenomenon of the great book turning into agreat film—the sort of best-case scenario. And so we did a fewof those. We did Great Expectations, for example, the DavidLean film along with the novel.Did any work less well than you hoped?We also had Scorcese’s Age of Innocence with the Whartonnovel, and Lampedusa’s The Leopard along with Visconti’s film.The one that didn’t work was John Huston’s film of Wise Blood,which in my memory had been very good, but when we saw itagain we thought it was rather weak. It just misses it—missesthe darkness, with a lot of hillbilly music which makes it all seemjokey. It removes completely the essence of the book. A certainamount depends on what you can find good quality prints of.Still, it was clear that there were many more than one could do ina single seminar.So I think I might do it again next year with different movies.I think I want to do the first of Ray’s Apu Trilogy, Pather Panchali[Song of the Little Road], which is the film that I would choosewhen asked for the greatest film ever made. In my view CitizenKane would probably come second.12 fall 2010fall 2010 13

I had a great desire to be outside the academy and in some other kind of world.And especially as I had already begun to harbor the dream of becoming a writer,I thought, you know, you’ve got to get into the world if you’re going to write about it.And in spite of all its eccentricities, I think Kubrick’s film ofLolita is wonderful. Even though he’s ridiculously too old, andso is the girl, nevertheless it has that astonishing performanceby Shelley Winters as Lolita’s mother, and Peter Sellers as ClareQuilty. Also John Huston’s film of Joyce’s The Dead. Much betterthan his film of Wise Blood.There’s also a very rare film that I’d be interested in teaching.It’s a Polish film by Wojciech Has called The SaragossaManuscript, which is based on an early-nineteenth-centuryPolish classic rather more wordily called The Manuscript Foundin Saragassa, by an eccentric nobleman called Jan Potocki. Sortof early magical realism, it’s about a traveler in a valley full ofghosts and monsters and the like, and hanged men who cometo life. Wonderfully zany book.How do you find students’ reactions to suchstories and films? Do they find them unsettlingat all, in not telling you what to thinkabout them, forcing you to make up your ownstory in a way?I don’t know whether it’s that the people selected to be in thisseminar are more sophisticated, but these kids all seemed toget it, easily. And certainly what I haven’t had is a desire forold-fashioned form. I’ve been teaching short stories this year,and it’s interesting how many of the best contemporary shortstories, if they’re not actually surrealist, go somewhere verynear that edge. It may have something to do with the intensificationof reality that happens in a story, that it pushes itselfnaturally toward something very strange. It’s been very interestingfor me, actually, to spend this time reading so many stories.Because what’s great about teaching stories is there’s suchdiversity there, all kinds of different ideas coming into my ownthoughts but also into the conversation. So it’s been fun; I’veenjoyed doing it.I realize this admits of a Marx Brothersanswer, but how have you found the<strong>Emory</strong> students?I’ve been very happy about it. Because, to be frank, if thestudents weren’t smart this would be a very bad gig. If you’reteaching students who can’t see what you’re trying to say, thenyou’d think: Well why am I doing this—I’ve already got a job.But it’s the opposite, really. Of course there are some who arebetter in their written work than in the classroom, and you haveto weigh that up as well. Because shyness is shyness.Is there an initial period in which students arescared or intimidated by you?The first fifteen minutes of the first class, yes. Perhaps even less.For me it’s strange because I don’t scare myself. It really doesn’toccur to me, walking into a room, that people are going to betongue-tied or awestruck or whatever it might be. I mean, it’sjust me. I’m a pretty informal person, and I think once they seethat . . . For instance, this year, as it happened, the first class wasjust before I had to go do some more formal event so I was quiteformally dressed. That created a kind of ice to break. The nextweek when I turned upwearing jeans, one ofthem said, “Oh I see,we’re very informal thisweek.” It just takes alittle moment to getthrough that.On paper or in person, they don’t evinceany fear of being in the presence of acapital-W Writer?No, they don’t seem to. Sometimes in the first week I have toencourage them to say and write more. But they do, and it’salways good.Did you ever want to be a teacher? Yourmother was a teacher, wasn’t she?She was, yes, before she was married. She taught muchyounger children, in primary school. No, I always thought thatmy failing would be that I am quite impatient. So I thought itwould become annoying and that I actually wouldn’t enjoy it.I just thought I wasn’t temperamentally suited for teaching.Also I remember in my final year at university, being really readyto leave. I didn’t stay on for graduate work. I remember thinking inmy final term that I’d had a really good time, and really liked beingat Cambridge, and found it very nourishing, and it has indeed leftme with a host of rich memories, and quite a few friends. So it wasa really positive experience in every way. Yet at the end of threeyears, I thought, I’m out of here. I had a great desire to be outsidethe academy and in some other kind of world. And especially asI had already begun to harbor the dream of becoming a writer,I thought, you know, you’ve got to get into the world if you’regoing to write about it.At Cambridge especially, more than at Oxford, you can liveinside that little enchanted bubble, and the real world is . . . overthere somewhere. And I loved being in the bubble. I thought it wasa beautiful place to be. It was impossible not to be stunned by thebeauty. I would wake up and look out my window and there wasKing’s Chapel, and I would think, what a thing it is to have that asyour view. And the great library at Trinity, and you could go to theroom where Isaac Newton discovered the theory of gravity.Since then, though, I never thought about teaching. Andthen in the five or six years before I started coming here,I started to do a bit of stuff on the lecture circuit, goingto universities just for a day or two, giving a set-piece lectureand then maybe teaching a smaller class of literaturestudents, and I discovered that it was quite enjoyable, andworthwhile. I still wondered whether I would be good at thedaily grind of it, because teaching of course is hard work. Butit was nourishing for me, also, to be in touch with these youngminds. And then this archive business happened, and only afterthat, President Wagner said, “Well, now that we’ve got all yourpapers, how would you feel about teaching a bit?”What were your first thoughts about that?Well, the problem of being a writer is, you have to becomevery good at protecting your time. Because there are endless—often very interesting—offers being made to come here, dothis, go there, and nobody ever says to you: Stay at home fortwo months and work. You have to be the person saying thatto yourself. And so I was concerned that it might just preventme from working for a while. One of the most pleasurablediscoveries of the first year was that the opposite was the case.There was the teaching, and that took up part of my week, butI found that I actually did a lot of writing. Fifty or sixty pages ofThe Enchantress of Florence got done while I was here, and lastyear when I was writing Luka and the Fire of Life, I did quite abig chunk of it while I was here.Then I thought, well those are the two worries I had, thatthe students wouldn’t be good and that I wouldn’t be able todo any of my own work. And the opposite turned out to betrue, in both cases. At that point I thought, Hang on to this.14 fall 2010fall 2010 15

The Class of 2014 does it bythe numbers on the quad16 fall 2010 fall 2010 17

Why do filmmakers return to this ground?Has the passing of decades done anything torewrite the moral ledger recording victims andperpetrators? The fullest answer resides in thecase itself.Featured TitleScreening a Lynching:The Leo Frank Case on Film and Televisionby Matthew Bernstein<strong>University</strong> of Georgia Press, 2009Matthew Bernstein is professor and chair of filmstudies. He joined the <strong>Emory</strong> faculty in 1989.were on the horizon. On Thanksgiving Day 1915, just threemonths after Frank’s lynching, an estimated fifteen “Knights ofMary Phagan” joined traveling Methodist minister Colonel WilliamJ. Simmons in a ceremony at Stone Mountain, ten miles east ofAtlanta, to revive the Ku Klux Klan (KKK); the burning cross theylit on the mountainside was visible for miles in every direction.These men anointed Atlanta the national capital of the InvisibleEmpire—a designation that would endure for decades. . . .These four visualizations of the case show how the veryelements that made the Phagan-Frank story irresistible tovisual storytellers often proved too complex, contradictory,or ambiguous to be given their due. The case was a traumaticevent in American history, and this is another reasonstorytellers keep returning to it. Any representation of trauma—and of history more generally—is an attempt to process andcomprehend what is disturbing in human experience. The mostrecent and dramatic example of this dynamic is the appearanceof television and theatrical films such as United 93 four yearsafter the terrorist attacks on America of September 11, 2001.Yet whether the trauma in question is personal or national inscale, its representation is informed by ruptures and gaps inthe telling; its depiction always pushes against the limits ofwhat can be represented—as critics and theorists of traumaticrepresentation would have it, the portrayal of trauma involvesdramatizing what cannot be expressed.Excerpt:Recent <strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong> Faculty BooksIn August 1915, in the woods outside Marietta, Georgia,a mob of angry white southerners lynched a man forrape and murder. Neither the event—a well-planned act ofvigilante violence—nor the inspiration—the alleged violationand murder of a white woman—was particularly unusual atthat time and place in American history. What was unusualwas the race of the man at the end of the rope. He was white.Stranger still, his fate was sealed not by his crime but by hisreligion. He was Jewish.The victims—I overtly use the plural here—were Leo Frankand Mary Phagan. As the title of Mervin LeRoy’s 1937 film aboutthe matter prophesied of all those who learn of the case, “Theywon’t forget.” And indeed, few have. In some ways, though,the better question is: Why do so many still remember? MaryPhagan’s murder was one of thousands of crimes committed in1913, and the lynching of Leo Frank in 1915 was just one of anestimated 288 such acts perpetrated against white Americansbetween 1882 and 1930. And this number pales in comparisonwith the estimated 2,500 black lynchings between 1880 and1930—nearly one per week during a fifty-year span, all withoutthe benefit of a trial and “at the hands of persons unknown.”For many Americans, the Phagan-Frank case has been anobsession out of proportion to its status as a discrete historicalevent in a rough-and-tumble time. All manner of artists—songwriters,novelists, journalists, playwrights, and filmmakers—have considered it worthy subject matter. This volume looksat the two surviving theatrical films and the two televisionprograms (shot on 35 mm film) depicting what befell Phaganand Frank. Why do filmmakers return to this ground? Has thepassing of decades done anything to rewrite the moral ledgerrecording victims and perpetrators? The fullest answer residesin the case itself. . . .The Phagan-Frank case reflected and was shaped by manyinterlocking cultural tensions of the period. Mary Phagan camefrom a family of tenant farmers forced to move into the cityto seek factory and mill work. The working conditions she andothers found were what we today would call sweatshops. Suchcircumstances inflamed southern populists’ resentment ofindustrialization, modernization, and child labor. . . .Gender played a role as well. The unfounded charge thatFrank had attempted to rape Phagan played on commonly heldfears about what vulnerable daughters faced when they left thesafety of the family for the viper’s nest of the city and factory. . . .What befell Atlanta’s Jews in the trial’s aftermath is certainlynot in doubt. Jewish schoolchildren were cursed and stoned asthey walked to school, and stores owned by Jews were vandalized.Acting on their horror at what some called an “AmericanDreyfus case,” Jewish leaders of B’nai B’rith—the Jewish fraternalorganization whose Atlanta chapter Frank had led—formed theAnti-Defamation League in 1913 to combat anti-Semitism andprejudice of all kinds. . . . If the Frank case gave Atlanta’s Jewsreason enough to be fearful, equally ominous developmentsAlan Abramowitz. The Disappearing Center.Geoffrey Bennington, ed. The Beast and the Sovereign.----, ed. Not Half No End: Militantly Melancholic Essays inMemory of Jacques Derrida.Julia Bullock. The Other Women’s Lib.Erik Butler. Metamorphoses of the Vampire in Literatureand Film.Lilia Coropceanu. Faber Suae Fortunae.Kevin Corrigan. Evagrius and Gregory: Mind Soul and Bodyin the 4th Century.Lisa Dillman, trans. Op Oloop.Mikhail Epstein. Encyclopaedia of Youth.Shoshana Felman. Theaters of Justice: Oscar Wilde Revisited.Skip Garibaldi. Cohomological Invariants.Sander Gilman. Obesity: The Biography.Anna Grimshaw. Observational Cinema: Anthropology,Film and the Exploration of Social Life.William Gruber. Offstage Space, Narrative, and the Theatreof the Imagination.Fraser Harbutt. Yalta 1945: Europe and America atthe Crossroads.Dalia Judowitz. Drawing on Art: Duchamp and Company.Kevin Karnes. Baltic Musics/Baltic Musicologies.Harvey Klehr. The Communist Experience in America.Melvin Konner. The Evolution of Childhood: Relationships,Emotions, Mind.Ruby Lal. Domesticity and Power in the Early Mughal World.Tong Soon Lee. Chinese Street Opera in Singapore.Jeffrey Lesser. Kasato Maru.Anthony Martin. The Dinosaur That Dug Its Burrow.Richard Martin, co-ed. Islamism: Contested Perspectiveson Political Islam.Michael McCormick. Organic Chemistry Laboratory Manual.Claire Nouvet. Enfances Narcisse.----. Abelard et Heloise: La passion de la maitrise.Stephen Nowicki. Starting Your Kids Off Right.Karla Oeler. A Grammar of Murder: Violent Scenes andFilm Form.Jeffrey Staton. Judicial Power and Strategic Communicationin Mexico.Kenneth Stein. History, Politics and Diplomacy of the Arab-Israeli Conflict.Natasha Trethewey. Beyond Katrina.Kristin Wendland. Fundamentals of Tonal Music forAnalysis and Composition.Maisha Winn. Black Literate Lives.Kevin Young. Breviary.18 fall 2010fall 2010 19

Delores AldridgeNotable Faculty AchievementsIn the midst of two weeklong, back-to-back sociology conferences,Dr. Delores Aldridge has just a brief moment ather desk to discuss her latest honors, but she speaks with agrace that belies her jam-packed schedule. The Grace TownsHamilton Professor of Sociology and African American Studies,Dr. Aldridge was, in 1971, the first female African Americanfaculty member hired by <strong>Emory</strong>; since then, she’s conductedresearch and led initiatives involving everything from betteringconditions for African American communities to helping endapartheid to supporting sustainable development projects inWest Africa. Along the way, she’s earned dozens of awards—three in 2010 alone.After more than four decades of work in sociology and socialjustice, including civil rights–era demonstrations that landed herin jail, Dr. Aldridge considers the present moment the “apexof my career.” That judgment was certified by her most recenthonor, the Cox-Johnson-Frazier Lifetime Achievement Award,presented by the American Sociological Association at its conferenceon August 15. Presenting the award, selection committeechair Mary Johnson Osirim called Aldridge a pioneer exemplifyingthe tradition of the sociologists for whom the award is named,“a scholar-activist [who] makes us truly proud to be sociologists.”“It is just so special to be recognized by folk who have doneso much themselves,” Dr. Aldridge says, noting that the attendanceof thousands of fellow sociologists, including a number ofher previous doctoral students, made winning the Cox-Johnson-Frazier an especially meaningful experience.In March, Dr. Aldridge received the Trailblazer Award (for“pioneering personal achievements, outstanding leadership,contribution and continued support to the organization”)from the Association of Social and Behavioral Scientists whereshe has served as president and continues to sit on the W.E.B.DuBois Award selection committee. Her accomplishments atthe <strong>University</strong> have been equally trailblazing, having foundedthe first degree-granting African American Studies program inthe south and led it for twenty years. Besides being a dedicatedteacher and mentor at <strong>Emory</strong>, she has served on the board oftrustees at Clark Atlanta <strong>University</strong>, one of her alma maters,and funded scholarships and university development in Ghanathrough her Kess Nsona Foundation.Dr. Aldridge has worked, in fact, with more than 90 foreigngovernments, federal and local agencies and non-governmentinstitutions, and has held political appointments in DeKalb Countyand served two terms as president of the National Council forBlack Studies. She’s also published widely on her core concernsof race, gender, social justice and human rights, making her ahighly visible and sought-after scholar—as further evidenced bythe National Black Herstory Task Force, which in March inauguratedan honor in her name: the Delores P. Aldridge AcademicAchievement Award. That namesake honor joins <strong>Emory</strong>’s ownDelores P. Aldridge Excellence Awards, established in 2003, andClark Atlanta <strong>University</strong>’s Aldridge-McMillan Faculty and StaffAchievement Award.Even after earning so many accolades for her work and service,Dr. Aldridge maintains a sense of indebtedness to the scholarlycommunity in which she has flourished. “Receiving the AmericanSociological Association lifetime achievement award was a hugehonor,” she says. “I have many awards, but with each one I get,I become more humbled.”—Marc SchultzGeorge Armelagos, Goodrich C. White Professor ofAnthropology, delivered the twenty-ninth Journal of AnthropologicalResearch Distinguished Lecture in September 2009.Jose Boigues-Lopez, senior lecturer in Spanish, received theWinship Award for Senior Lecturers.Herbert Bonario, Professor Emeritus of Classics, received aSpecial Service Award from the Classical Association of the MiddleWest and South.Joel Bowman, professor of chemistry, was a Visiting Fellowat Magdalen <strong>College</strong>, Oxford <strong>University</strong>.Patricia Brennan, professor of psychology, was made a fellowof the Association for Psychological Science.Rudolph Byrd, Goodrich C. White Professor of AmericanStudies, received the 2010 Governor’s Award in the Humanities,<strong>Emory</strong>’s Thomas Jefferson Award recognizing service to the<strong>University</strong>, and the Dick Bathrick Award from the group MenStopping Violence against Women.Ronald Calabrese, Samuel C. Dobbs Professor of Biology,and Paul Lennard, director of the Neuroscience and BehavioralBiology program, received “Courage to Inspire” awards from theNeuroscience Initiative.Monica Capra, assistant professor of economics, received thePhi Beta Kappa Award for excellence in teaching.Cathy Caruth was named Samuel C. Dobbs Professor ofComparative Literature and English and appointed M. H. AbramsDistinguished Visiting Professor at Cornell <strong>University</strong>.Tom Clark, assistant professor of political science, won theBest Paper Congressional Quarterly Press Award, an EmergingScholar Award from the Midwest Political Science Association,and the Carl Albert Dissertation Award from the AmericanPolitical Science Association.Vincent Conticello, professsor of chemistry, CarlaFreeman, Winship Distinguished Professor of Anthropology andWomen’s Studies, Skip Garibaldi, associate professor of mathematicsand computer science, and Alexander Hicks, WinshipDistinguished Professor of Sociology, have received the WinshipDistinguished Research Award.Frans B. M. de Waal, C. H. Candler Professor of PrimateBehavior, received an honorary degree from the <strong>University</strong> ofHumanistics, Utrecht, the Netherlands, a medal from the Societyof Medicine and Natural Science, Parma, Italy, and the C. U. AriensKappers Award from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences.William Dillingham, Professor Emeritus of English, had hisbook Being Kipling named an “Outstanding Academic Title for2009” by Choice.Richard Doner, professor of political science, James Nagy,professor of mathematics and computer science, and DeborahElise White, associate professor of English and comparativeliterature, received the 2010 <strong>Emory</strong> Williams Award forDistinguished Teaching.Timothy Dowd, associate professor of sociology, was namedco-editor of Poetics: Journal of Empirical Research on Culture,the Media and the Arts.Astrid Eckert, assistant professor of history, won the BerlinPrize of the American Academy in Berlin, where she will be afellow in spring 2011.George Engelhard, professor of educational measurement,became a fellow of the American Educational Research Associationand associate editor of Applied Measurement in Education.Yayoi Uno Everett, associate professor of music theory, wasnamed a senior fellow at the Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiryfor 2010-11.Shoshana Felman, Robert Woodruff Distinguished Professorof Comparative Literature and French, has been elected a fellowof the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.Robyn Fivush, Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor and chair ofpsychology, was elected to the American Psychological AssociationBoard of Scientific Affairs.James Flannery, Winship Professor of Arts and Humanitiesand director of the Yeats Foundation, was named an InternationalAssociate Artist at the Abbey Theatre and a visiting professor at<strong>University</strong> <strong>College</strong>, Dublin.Tyrone Forman, associate professor of sociology, has beenawarded an Alphonse Fletcher Sr. Fellowship.20 fall 2010fall 2010 21

Notable Faculty Achievements (continued)Frances Smith Foster, Charles Howard Candler Professor ofEnglish and women’s studies, received the Jay B. Hubbell Medal foreminence in American literary scholarship, the Francis Andrew MarchAward for contributions to the profession of English, the <strong>College</strong>Language Association Creative Scholarship Award, and an honorarydegree from the State <strong>University</strong> of New York–Geneseo, where shedelivered the commencement address.Justin Gallivan, associate professor of chemistry, was madea Kavli Frontiers of Science Fellow by the National Academyof Sciences.Jennifer Gandhi, associate professor of political science, receivedthe Award for Conceptual Innovation in Comparative Politics from theInternational Political Science Association.Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, professor of women’s studies,received the Senior Scholar Award from the Society forDisability Studies.Andra Gillespie, assistant professor of political science, receivedthe Norton Long Scholar Award from the American Political ScienceAssociation and was Martin Luther King Visiting Professor at MIT.Sander Gilman, Distinguished Professor of the Liberal Arts andSciences, served as Distinguished Visitor at Ben Gurion <strong>University</strong>,Cecil Green Visiting Professor at the <strong>University</strong> of British Columbia,and Visiting Professor at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London.Eric Goldstein, associate professor of history, was named a fellowof the Sami Rohr Institute for Jewish Literature and a DistinguishedLecturer by the Organization of American Historians.Sherryl Goodman, professor of psychology, has been appointededitor of the Journal of Abnormal Psychology.Carole Hahn, Charles Howard Candler Professor of EducationalStudies, received a Leverhulme Fellowship.Karen Hegtvedt, professor of sociology, and CathrynJohnson, associate professor of sociology, have been namedco-editors of Social Psychology Quarterly.George Hentschel, professor of physics, was named anOutstanding Referee by the American Physical Society.Craig Hill, Goodrich C. White Professor of Chemistry, wasinvited to speak on green energy and to lead discussion withpresidents of 130 U.S. scientific societies and the Undersecretaryof Energy in May.Kevin Karnes, associate professor of music history, receivedthe Vilis Vitols Prize in Baltic Studies from the Association for theAdvancement of Baltic Studies.Diane Kempler, senior lecturer in visual arts, was awardeda residency at the International Ceramic Center in Denmark.Gary Laderman, professor of religion, has received the WinshipDistinguished Research Award.Thomas Lancaster, professor of political science, was named<strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong>’s Distinguished Scholar-Teacher of the Year.Steven L’Hernault, professor and chair of biology, was appointedVisiting Professor at Northwest A&F <strong>University</strong>, People’s Republicof China.Deborah Lipstadt, Dorot Professor of Modern Jewish Historyand Holocaust Studies, was made a Resnick Fellow at the UnitedStates Holocaust Museum and a fellow of the American Academyof Jewish Research.Peter Little, professor of anthropology, was elected a fellow ofthe Society for Applied Anthropology.Valerie Loichot, associate professor of French and Italian, was asenior fellow at the Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry for 2009-10.Timothy McDonough, associate professor of theater studies,won the Suzi Bass Award for Outstanding Featured Actor.Walter Melion, Asa G. Candler Professor of Art History, has beenelected to the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.Andrew Mitchell, assistant professor of philosophy, has beenawarded a fellowship from the National Endowment for theHumanities for a pilot course, following a 2009 NEH fellowship totranslate Heidegger.Tracy Morkin, lecturer in chemistry, won the William Fox CrystalApple Award for Emerging Excellence.Laura Namy, associate professor of psychology, became editorof the Journal of Cognition and Development.Laura Otis, professor of English, was cited for Outstanding Bookon the History of the Neurosciences for Müller’s Lab.Albert Padwa, William P. Timme Professor of Chemistry,became a fellow of the American Association for Advancementof Science and was #5 on the Journal of Organic Chemistry’s listof most prolific authors.Bobbi Patterson, senior lecturer in religion, receivedthe 2010 Excellence in Teaching Award from the AmericanAcademy of Religion.Beth Reingold, associate professor of political science, receiveda fellowship to the Hoover Institution at Stanford <strong>University</strong> and aBest Paper Award from the American Political Science Association.Michael Rich, associate professor of political science, receivedthe Presidential Award from the U.S. President’s Higher EducationCommunity Service Council.James Rilling, associate professor of anthropology, was aVisiting Senior Research Fellow at Oxford <strong>University</strong>.Khalid Salaita, assistant professor of chemistry, has receiveda 2010 Cancer Research award.Don Seeman, associate professor of religion, was madea Hartman Fellow at the Kogod Center for ContemporaryJewish Thought.Vanessa Siddle Walker, professor of educational studies,was made a fellow of the American Educational ResearchAssociation, received a W.E.B. DuBois Distinguished LecturerAward, and was invited to the Stanford Center for AdvancedStudy in the Behavioral Sciences.Natasha Trethewey, Phillis Wheatley Distinguished Chair ofCreative Writing, was inducted into the Fellowship of SouthernWriters and the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame, recognized foroutstanding achievement by the Georgia state legislature, andreceived a James Weldon Johnson Fellowship from the BeineckeLibrary and the Richard Wright Award for Literary Excellence.Irwin Waldman, associate professor of psychology, is president-electof the Behavior Genetics Association.Elaine Walker, Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Psychologyand Neuroscience, received the Joseph Zubin Award from theSociety for Research in Psychopathology.Kristin Wendland, senior lecturer in music theory, was nameda Community-Engaged Learning Faculty Fellow by <strong>Emory</strong>’s Officeof <strong>University</strong>-Community Partnerships.Regina Werum, associate professor of sociology, was FoxCenter for Humanistic Inquiry Senior Fellow for 2009-10 and hasaccepted a two-year appointment as Sociology Program Directorat the National Science Foundation.Li Xiong, assistant professor of mathematics and computerscience, was awarded a Women’s Institute Summer EnrichmentFellowship, one of twenty nationally.Kevin Young, Atticus Haygood Professor of English andCreative Writing, was a James Baldwin Fellow for 2009, won theGraywolf Nonfiction Prize for 2010, and had his poem “LimeLight Blues” selected for Best American Poetry 2010.Kathryn Yount, associate professor of sociology, was a<strong>University</strong> Research Board Visiting Scholar at the American<strong>University</strong> in Beirut.22 fall 2010fall 2010 23

Recent Faculty GrantsWorking with a development team, the Laynes established a unique“Adopt-a-Traveler” scholarship for undergraduates at <strong>Emory</strong>.The Gift of Travel: Jonathan and Sheryl LayneGeoffrey Bennington, French and Italian—<strong>University</strong> ofSouthern California, National Endowment for the HumanitiesAviad Brisman, Peter Brown, Craig Hadley, DavidNugent and Lesley Weaver, anthropology; ToddSchlenke and Neil Milan, biology; Joel Bowman,Huw Davies, Michael Heaven, Craig Hill, JamesKindt, Dennis Liotta, David Lynn, Keiji Morokuma,Djamaladdin Musaev and James Snyder, chemistry;Keith Berland, Kurt Warncke and Eric Weeks,physics; Thomas Clark, political science—NationalScience FoundationGray Crouse and Yun Tao, biology; Timothy Acker andDennis Liotta, chemistry; Uriel Kitron, environmentalstudies; Donna Maney and Widaad Zaman, psychology—National Institutes of HealthCraig Hill, chemistry—TDA Research, HDTRAHarvey Klehr, political science—Apgar FoundationBruce Levin, biology—Procter & GambleTianquan Lian and Stefan Lutz, chemistry—LonzaStella Lourenco, psychology—John Merck FoundationCarol Herron Lustig—Public Broadcasting FoundationStefan Lutz, chemistry—Research Corporation forScience AdvancementPatricia Marsteller, Center for Science Education—Arthur M. Blank Family FoundationWhile Jonathan and Sheryl Layne wereequally committed to establishing theAdopt-a-Traveler program, they haddifferent reasons. For Sheryl, the fundwas another way to “pay it forward.”She and her family had been fortunateenough to travel extensively, and shesaw the program as a way to help giveamazing opportunities to deservingstudents. Sheryl’s participation in theprogram reflected her belief that travellinghelps students grow and enhancestheir educational experience beyondclassroom walls.For Jonathan, the value of studyingabroad was something he understoodfirsthand. As an undergraduate he spenta year studying abroad at universities inEngland and Poland. The experience, hesays, was deep, meaningful, and nothingshort of “life-altering.” Knowing howHuw Davies and Dennis Liotta, chemistry—GeorgiaResearch AllianceAndrew Mitchell, philosophy—National Endowmentfor the HumanitiesCharles Downey and Robert Jensen, educationalstudies—National Academy of EducationDeboleena Roy, women’s studies and NBB—NationalAcademies Keck Futures InitiativeMichael Elliott, senior associate dean of faculty—AmericanCouncil of Learned SocietiesThomas Gillespie, environmental studies—<strong>University</strong> ofOxford, Lincoln Park ZooThomas Gillespie and Michele Parsons, environmentalstudies—Morris Animal FoundationSwargajyoti Gohain and Bruce Knauft, anthropology—Wenner Gren FoundationJames Taylor, biology—Pennsylvania State <strong>University</strong>Eddy Von Mueller, film studies; Judy Raggi Moore,French and Italian; Peter Höyng, German studies; AngelikaBammer and Anna Grimshaw, ILA; Sissel McCarthyand Sheila Tefft, journalism; Susan Tomasi, linguistics;Amy Aidman, MARIAL; Vincent Cornell, MESAS;Kevin Karnes, music; Robert McCauley, philosophy;Wan-Li Ho and Yu Li, REALC; Eric Reinders, religion;Michael Evenden, theater studies—<strong>Emory</strong> Fund forInnovative TeachingLance Gunderson, environmental studies—BattelleElaine Walker, psychology—<strong>University</strong> of California–Los Angeles24 fall 2010fall 2010 25

To the Laynes, giving back was not a form of reimbursement but an opportunityto convey a real thank you—to a place that had made a difference in their livesand was making a difference in the world.The Gift of Travel: Jonathan and Sheryl Layne (continued)Darcy Levit 90CPresident, <strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong> Alumni Boardmany worthy and exceptional studentswere at <strong>Emory</strong>, Jonathan wanted to providesupport for those whose own goalsmight take them to distant surroundingsin search of new perspectives.The Laynes met at <strong>Emory</strong>. Over timethey embarked upon life’s adventurestogether and supported one other’sstudies and pursuits; they traveled, gotmarried, had a family. They had barelyleft campus before they began makingfinancial contributions to the <strong>University</strong>,as a way to give thanks for the supportand positive experiences they felt <strong>Emory</strong>had provided them. When the opportunityarose years later to design a givingprogram, the Laynes wanted their gift toinclude one essential component: travelabroadopportunities for students.Working with a developmentteam, the Laynes established a unique“Adopt-a-Traveler” scholarship forundergraduates at <strong>Emory</strong>. The new programcreated a mechanism to supportstudents who want to study outsideof the United States during the summer,but who otherwise might not be able todo so for financial reasons. To assist suchstudents, the Laynes bestowed a multiyeargift to sponsor one student’s travelexpenses each summer.To the Laynes, giving back was nota form of reimbursement but an opportunityto convey a real thank you—toa place that had made a difference intheir lives and was making a differencein the world.Like its sister program Adopt-a-Scholar, Adopt-a-Traveler pairs a generousbenefactor with an academicallygifted student and sends the donor aprofile of the scholar. As is often trueof these types of programs, strongbonds are forged between recipientsand donors. In the case of the Laynes’gift, the impact—and the experience ofstudying abroad—went far beyond eitherside’s expectations.Victoria Bell was the student withwhom the Laynes were paired. A doublemajor in biology and environmentalstudies with an impressive record of<strong>University</strong> service and extracurricularactivities, Victoria was the type ofengaged scholar that <strong>Emory</strong> is proud toeducate. The support provided by theLaynes enabled Victoria to backpackthrough Namibia and Botswana, trackingthe desert elephants of Africa fora research project. She had dreams ofa career in medicine and wrote to theLaynes about her work in a geneticslaboratory at <strong>Emory</strong> and her interest inresource management.To thank the Laynes, Victoria createda scrapbook of her experiences duringher summer abroad. She wanted herphotos and correspondence to showthem that they were, in fact, right therewith her as trekked through the Africancountryside. In her initial letter, shewrote: “Hopefully, this scrapbook canbe a window into what I experiencedand learned while I was abroad—andreassure you that your donation. . . willmake a difference for one lucky studentlike myself, just dying to have a life-alteringexperience.”As seasoned philanthropists, theLaynes had committed resources to<strong>Emory</strong> and other community organizationsfor years. But the experience offunding students through the Adopt-a-Traveler program brought unexpectedlevels of satisfaction. As Sheryl explains,“I just don’t think I realized the extentto which this would change a life—andhow happy it makes John and me toknow that. You have touched someone’slife in a meaningful way. Youhave made an impact on her, but you’rechanged too. She is one of the studentsat <strong>Emory</strong> who want to go out there andchange the world. And I am convincedthat they will.”Gratitude for opportunities extendedthirty years ago is benefitting students at<strong>Emory</strong> today, thanks to alumni like Sheryland Jonathan Layne. Through this programthe Laynes are not only thanking aninstitution but investing in students whowant to do good and to make a differencein the world.—Tiffany WorboyFor more information about how youcan help provide life-altering experiencesfor exceptional students like VictoriaBell, please contact the <strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong>Development Office at artsandsciences@emory.edu or 866-MY-EMORY.Darcy Levit is the newly elected president of the <strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong> AlumniBoard. With more than twenty years of experience coordinating volunteers andworking in nonprofit organizations, Darcy believes in the impact of volunteerand philanthropic leadership. She served as president of Volunteer <strong>Emory</strong> duringher senior year at <strong>Emory</strong> and earned an MS in policy studies from GeorgiaState <strong>University</strong>, positioning her for a career in the nonprofit arena.Most recently, Darcy has served as director of development at the PotomacConservancy and executive director of the Audubon Society of NorthernVirginia. Before that she was chief development officer at the NationalMuseum of Women in the Arts. Darcy has also volunteered in fundraising andcorporate development for Zoo Atlanta and the Atlanta Humane Society.Darcy lives in Northern Virginia, where with her children and standardpoodle she frequents local parks to hike, bike and observe the natural beautyof the area. She enjoys meeting <strong>Emory</strong> alumni in Washington, D.C., for visitsto art museums, theaters, live music and ballet performances. Her localvolunteer commitments have included park clean-up initiatives and hungerpreventionprograms.We’re excited to welcome seven newAlumni Board members in 2010-11Natascha French 02C (right) received a BA in journalism and internationalstudies from <strong>Emory</strong> and is the president and co-founder of the company “envy2the 9.” She has been very involved in professional and student committeesand as a member of the <strong>Emory</strong> Alumni in Washington, D.C., Chicago and LosAngeles. She lives in Beverly Hills.Leigh Friedman 05C graduated with a BA in journalism and theater studies.She was a member of several <strong>Emory</strong> honor societies and was president ofAlpha Delta Pi executive editor of the Wheel. A regional marketing managerfor ESPN, she resides in Baltimore and volunteers with numerous local charitiesand groups.Carlos Gonzalez 97C (right) received his BA in political science and NearEastern studies before graduating from Northwestern <strong>University</strong> School of Law.He is a partner in the firm Diaz, Reus & Targ with a specialty in litigation andinternational law. While at <strong>Emory</strong>, Carlos was honored with awards for debateand academic excellence. A member of the British American Business Counciland the Greater Miami Chamber of Commerce, he lives in Miami.26 fall 2010fall 2010 27

Have a plan.We’re excited to welcome seven new Alumni Boardmembers in 2010-11 (continued)Theron Jones 94C (left) received his BA in chemistry from <strong>Emory</strong> in 1994,a master’s of public policy from UCLA in 2000 and his doctorate of dentalmedicine in 2004 from the Medical <strong>College</strong> of Georgia. The owner ofSandtown Family Dentistry in Atlanta, Dr. Jones has volunteered with theAtlanta Youth Council, the American Cancer Society, Leadership in DiverseCommunities, The Carter Center, the Voting Rights Institute, and UCLA’sMinority Outreach Program.Jane Goodman Preiser 81C graduated with a BA in psychology from<strong>Emory</strong> and received a master’s of health services administration from GeorgeWashington <strong>University</strong>. Her community involvement includes fundraising forGreens Farms Academy, the Westport Playhouse, a Near and Far outreach forthe homeless, and the United Way Campaign. Her daughter Alexandra isa freshman at <strong>Emory</strong>. Jane lives in Westport, Connecticut.Sanjiv Reej 95C earned his BA in English from <strong>Emory</strong> and a master’s ofhealthcare administration and MBA from Georgia State <strong>University</strong>. He currentlyworks in sales and marketing for Pfizer Pharmaceuticals. A member ofthe <strong>Emory</strong> Wind Ensemble, Sanjiv has participated in <strong>Emory</strong> Career Network,Boston <strong>Emory</strong> Cares, and resides in Longmeadow, Maryland.Joshua Teplitzky 82C 86B 86L received his BA in political science, as well asbusiness and law degrees, from <strong>Emory</strong>. He is an attorney with Teplitzky andCompany specializing in tax law. Joshua is a member of the <strong>Emory</strong> ParentAssociation and the New York/Connecticut Alumni Association, and is vicepresident of the Hygeia Foundation. His daughter Taylor is a student at <strong>Emory</strong>.Joshua resides in Woodbridge, Connecticut.GrowinG up in the small-town South,Jane Gatewood 98C set her sights on theworld. As a high school student in phenixCity, Alabama, she served as a summerambassador to russia. At <strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong>,she thrived among the diverse student bodyand studied abroad at oxford universityin England.That way, no matter where life takes her, she’llbe able to strengthen the college she loves.Learn how you can support <strong>Emory</strong> with aplanned gift, which offers tax and incomebenefits. Visit www.emory.edu/giftplanningor call 404.727.8875.28 fall 2010now she travels the globe for the office ofinternational Education at the universityof Georgia. Grateful to <strong>Emory</strong> for helpingprepare the way, she has designated apercentage of her estate to <strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong>.fall 2010 29Plan to share your journey.

<strong>Emory</strong> <strong>University</strong><strong>Emory</strong> <strong>College</strong> of arts and sciences400 Candler Library550 Asbury CircleAtlanta GA 30322