pdf, 1597k - Marine Conservation Agreements

pdf, 1597k - Marine Conservation Agreements

pdf, 1597k - Marine Conservation Agreements

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Ecological modernization ofmarine conservationA case study of two entrepreneurial marineprotected areas in IndonesiaMariska BottemaMSc ThesisJuly 2010Wageningen University, Wageningen

The photograph on the front cover shows a Gili Trawangan dive boat taking touristsout to dive ‘Meno Wall’, a popular dive site at the neighboring island (source: author).2

Wageningen University – Department of Environmental SciencesEnvironmental Policy GroupEcological modernization of marineconservationA case study of two entrepreneurial marine protectedareas in IndonesiaMariska BottemaMSc thesisMaster Environmental SciencesSupervisor:Dr. Simon BushEnvironmental Policy (ENP)3

AcknowledgementsThere are quite a few people I need to thank for their contribution and help throughout theprocess of writing this thesis.I want to begin with mentioning a few people that were invaluable to me before and during myfield work in Indonesia. First of all a big thank you goes to Tom Goreau for his instantenthusiasm and for the initial introduction to the projects in Bali and Lombok. I want to thankNara for welcoming me to Pemuteran, helping me find a place to stay and making me feelright at home. A special thank you goes out to Komang who was kind and patient enough todrive me around on his scooter, introduce me to interviewees from the village, and even offerhis interpretation skills! Komang, Made and Putu gave me a sense of family in Pemuteran;they let me bother them every day at the Biorock Centre with questions and were happy tolend me snorkeling equipment for me to enjoy Pemuteran‟s reefs in my free time.I would like to thank Delphine in Gili Trawangan for being so open to a student like me, takingthe time to speak to me and leading me to the countless people in Trawangan who were kindenough to share their thoughts with me. Also, a thank you goes out to fellow researcher Edfor keeping me company between all the holiday-goers! Of course, I cannot forget to thankmy sister Tamar for patiently listening to my daily telephone reports on my adventures in thefield.Naturally I wish to thank Simon Bush, my supervisor at Wageningen University for hisvaluable advice and support throughout the entire research process. His lasting enthusiasmabout the topic was a prime motivator for me, especially during the last lap to shore.A final thank you goes to those people close to me, who have put up with me during thisentire process. I want to thank my parents who have been supportive and enthusiastic aboutmy thesis and Tamar for helping me out whenever I needed it. Lastly, a thank you goes out tomy friends in Wageningen and Den Haag, who have reminded me throughout the entireprocess how lucky I am for being able to go to some of the most beautiful places in the worldfor my master thesis!7

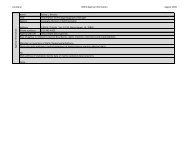

Table of Contents1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 131.1 Problem Statement........................................................................................................ 131.2 Objective ....................................................................................................................... 151.3 <strong>Marine</strong> conservation policy in Indonesia: the role of the state ...................................... 161.4 Private sector involvement in marine conservation: what is known? ............................ 191.5 Research methods and techniques............................................................................... 231.5.1 Case study ............................................................................................................. 231.5.2 Case selection: research sites ............................................................................... 241.5.3 Data collection: sources and methods ................................................................... 251.5.4 Limitations .............................................................................................................. 261.6 Outline of thesis............................................................................................................. 272 Theoretical Framework ......................................................................................................... 282.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 282.2 Ecological modernization .............................................................................................. 282.3 Shifts in ocean and coastal governance: increasing role of the private sector ............. 302.4 Entrepreneurship as a field of research ........................................................................ 332.5 Novel forms of entrepreneurship ................................................................................... 352.6 Social capital in entrepreneurship ................................................................................. 362.7 Institutionalization of entrepreneurship ......................................................................... 392.9 Framework for analysis ................................................................................................. 423 Pemuteran ............................................................................................................................ 433.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 433.2 History of fishing, tourism and marine conservation in Pemuteran ............................... 433.3 The „E‟ in the EMPA in Pemuteran................................................................................ 453.3.1 Opportunity 1: Developing tourism in Pemuteran .................................................. 453.3.2 Opportunity 2: Developing a sustainable diving industry in Pemuteran bay ......... 473.3.3 Opportunity 3: Adding value to the reef with Biorock ............................................. 493.3.4 Reflection ............................................................................................................... 513.4 Social capital of the entrepreneurs in Pemuteran ......................................................... 513.4.1 Interrelations in the private sector: dive operators and dive operators .................. 523.4.2 Private sector and local community ....................................................................... 533.4.3 Private sector and fishing community .................................................................... 553.4.4 Private sector and public sector ............................................................................. 573.4.4 Reflection ............................................................................................................... 573.5 Institutionalization of the EMPA .................................................................................... 583.5.1 Alteration of fishing industry norms: a ban and a No Take Zone .......................... 583.5.2 Privately funded enforcement: Pecalan Laut ......................................................... 603.5.3 Biorock ................................................................................................................... 623.5.4 Private sector projects ........................................................................................... 633.5.5 Reflection ............................................................................................................... 653.6 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 664 Gili Trawangan...................................................................................................................... 684.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 684.2 History of fishing, tourism and marine conservation in Gili Trawangan ........................ 684.3 The „E‟ in the EMPA in Gili Trawangan ......................................................................... 724.3.1 Opportunity 1: Developing tourism in Gili Trawangan ........................................... 724.3.2 Opportunity 2: Creating a collective dive industry to manage coral reefs ............. 734.3.3 Opportunity 3: Introduction of Biorock to Gili Trawangan ...................................... 744.3.4 Reflection ............................................................................................................... 769

4.4 Social capital of the entrepreneurs in Gili Trawangan .................................................. 764.4.1 Interrelations in the private sector: G.E.T .............................................................. 774.4.2 Private sector and local community ....................................................................... 784.4.3 Private sector and fishing community .................................................................... 804.4.4 Private sector and local security task force ........................................................... 814.4.5 Private sector and public sector ............................................................................. 824.4.6 Reflection ............................................................................................................... 834.5 Institutionalization of the EMPA .................................................................................... 844.5.1 Fishing agreement based on local ruling: Awig-awig ............................................ 844.5.2 Privately funded enforcement: SATGAS ............................................................... 854.5.3 Private sector alliance: Gili Eco Trust .................................................................... 874.5.4 Biorock ................................................................................................................... 894.5.7 Reflection ............................................................................................................... 914.6 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................... 925 Discussion ............................................................................................................................ 945.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 945.2 Entrepreneurship ........................................................................................................... 945.2.1 Exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities ......................................................... 945.2.2 Dependence on individuals in EMPAs ................................................................... 955.2.3 Evaluating the concept of entrepreneurship .......................................................... 955.3 Social Capital ................................................................................................................ 965.3.1 Competition and collectivity within the private sector ............................................ 965.3.2 Relations with initial resource owners .................................................................... 975.3.3 The social value of Biorock .................................................................................... 985.3.4 The role of funding in EMPAs ................................................................................ 985.3.5 Evaluating the concept of social capital ................................................................. 995.4 Institutionalization ........................................................................................................ 1005.4.1 Combining new institutions with existing traditional institutions .......................... 1005.4.2 State support: also important in EMPAs? ............................................................ 1005.4.3 The institutional role of Biorock ............................................................................ 1015.4.4 Territorialization of the coral reefs ....................................................................... 1025.4.5 Evaluating the concept of institutionalization ....................................................... 1035.5 Analyzing EMPAs through the eyes of ecological modernization ............................... 1036 Conclusions and Recommendations .................................................................................. 105References ............................................................................................................................ 109Appendix ................................................................................................................................ 115Appendix 1: Interview List ................................................................................................. 11510

List of tables and figuresTablesTable 1: Existing EMPAs p.21FiguresFigure 1: Coral Triangle Region p.24Figure 2: Map of case study sites p.25Figure 3: Framework for analysis p.33Figure 4: Map of Pemuteran p.43Figure 5: Map of „Kebun Chris‟ with marine area use rules for the public p.48Figure 6: Swimming and Snorkeling Rules p.50Figure 7: Network diagram displaying communicative relations in the EMPA p.52Figure 8: Biorock Centre and Karang Lestari Rules sign p.64Figure 9: Map of Gili Indah with dive sites p.68Figure 10: Zoning plan for muroami fishermen p.74Figure 11: Network diagram displaying communicative relations in the EMPA in 2001 and 2010 p.77Figure 12: Building a new Biorock structure p.77Figure 13: GET manager preparing sign p.8011

List of acronymsBKKPNBKSDABRFCTIEMPAEUGETGCRAHMMRKRISMONLBRGLMMAMFMFSOMTPMMAFMPAMCANCANGONTZSATGASTNCWWFBalai Kawasan Konservasi Perairan Nasional (National Institute for Aquatic<strong>Conservation</strong> Areas)Balai Konservasi Sumberdaya Alam (Agency for Natural Resources<strong>Conservation</strong>)Bali Rehabilitation FundCoral Triangle InitiativeEntrepreneurial <strong>Marine</strong> Protected AreaEuropean UnionGili Eco TrustGlobal Coral Reef AllianceHotel Managed <strong>Marine</strong> ResortKrisis Monitair (Asian economic crisis)Lombok Barat Regency GovernmentLocally Managed <strong>Marine</strong> AreaMinistry for Forestry<strong>Marine</strong> Fisheries Service Office<strong>Marine</strong> Tourism ParkMinistry for <strong>Marine</strong> Affairs and Fisheries<strong>Marine</strong> Protected Area<strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> AreaNatural <strong>Conservation</strong> AreaNon-Governmental OrganizationNo Take ZoneSatuan Tugas (security task force)The Nature ConservancyWorld Wildlife Fund12

1 Introduction1.1 Problem StatementCoral reef ecosystems are complex and diverse, and they have a number of very importantfunctions. They support an incredible diversity of marine life (Bell et al., 2006). Moreover, theyprovide ecological services in the form of storm and flood protection, but are also the sourceof many socio-economic benefits (Bell et al., 2006; Yeemin et al., 2006). Coral reefs arefundamental to the sustainable development of many coastal communities in tropicaldeveloping countries. They provide food and minerals to these communities, income to localfisheries, as well as income from tourism-related activities in and around these reefs (Bell etal., 2006; Svensson et al., 2009). Since in many cases a large percentage of the proteinintake of these coastal communities comes from fish, and many coastal communities dependon fishing and tourism for their livelihood, dependence on healthy reefs can be fairly high (Bellet al., 2006).Unfortunately surveys of the ecological status of coral reefs have indicated the ongoingdegradation of these ecosystems; they are highly threatened today and are in declineworldwide (Bell et al., 2006; Clifton, 2003). Many complex causes exist for what is sometimesreferred to as this „coral reef crisis‟ but there is a general consensus that there are two maincategories of pressure on these ecosystems; global-scale climatic change and local-scaleimpacts (Bell et al., 2006). Local impacts stem from natural phenomena such as storms, aswell as from human activity of the populations on these coasts (Bell et al., 2006).Geographical information systems mapping indicates that 60% of the world‟s reefs are at riskfrom pressure arising from human activity (Clifton, 2003). A number of the human impactswhich contribute to the destruction of reefs are deforestation as well as the use of fertilizers,herbicides and pesticides in agricultural practices which cause an increase in nutrient andsediment loads in the ocean; industrial effluents; modification of habitat through coastaldevelopment and tourism; destructive fishing practices; and overfishing (Bell et al., 2006;Goreau et al., 2005). These human-induced threats are particularly acute in South-East Asia,where 80% of the reefs have been found to be endangered by coastal development andfishing-related activities (Clifton, 2003).An important tool currently used in conventional marine biodiversity and fisheriesmanagement is conservation through <strong>Marine</strong> Protected Areas (MPAs) (WSSD, 2005). Theneed for more MPAs has been increasingly recognized in the past decade, and has been putforward in several international policy instruments and legislation (Bogaert et al., 2009;Svensson et al., 2009). However, in the last years there has also been an increasingperceived need and interest in coral reef restoration as a supplementary approach toconservation (Rinkevich, 2005; Spurgeon et al., 2000). The normative goal of MPAs isconservation, or the preservation, of original habitats. Hence, conservation biology places itsmain focus on „passive‟ measures, allowing natural processes to mitigate impacts, withminimal human interference (Rinkevich, 2005). However, many reefs are too degraded toallow the recovery of the coral, fish, and invertebrates to former levels due to the fact that thequality of the habitat is so badly degraded that reefs have lost most of their carrying capacityfor these species. Based on the severity and vast expanse of areas of coral degradation,there has been increasing discussion regarding the need for coral reef restoration as an„active‟ tool to supplement MPAs, illustrated by the recent development of an increasingnumber of coral restoration methods (Kojis et al., 2001). Until recently coral restoration wasnot widely accepted as a management option. The topic is a controversial one due to its highcost and the fact that is has yet to be proven to be effective on a large scale (Kojis et al, 2001;Spurgeon et al., 2000). However, during the past decade restoration projects have been morewidely employed on a small scale, with restoration ecology slowly developing into a newscientific discipline in environmental science (Rinkevich, 2005).As mentioned above, there are numerous approaches to coral restoration. Though directcoral transportation is still the most frequently applied method, other novel methods arecoming to the foreground (Rinkevich, 2005). Tom Goreau and Wolf Hilbertz of the GlobalCoral Reef Alliance (GCRA), strong proponents for using coral restoration as a tool to fight13

coral reef degradation, developed a new method of coral restoration referred to as Biorocktechnology; the GCRA‟s Biorock Ecosystem Restoration technology uses low voltagecurrents to grow limestone rock on steel structures in the sea (Goreau et al., 2005). Projectsusing Biorock have been set up in numerous locations, some more successfully than others.In this method coral is „created‟, thereby adding value in these reefs. What is evident aboutthis type of method is the dependency on initial investments in the materials needed for thistechnology. Without sufficient funding this technology cannot be implemented. Herein lies oneof the limiting factors of such a method; its inherent dependency on investment. Until now nogovernment or large funding agency has supported meaningful restoration efforts (Goreau etal., 2008). With governments‟ disinterest in investing in this type of reef restoration, and thelimitations in the capacity of local communities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs)in their ability to invest, who is going to pay? Furthermore, once this technology has beensuccessfully implemented, how will the healthy reef be maintained?The emergence of novel types of MPAs could potentially present part of the solution. Themajority of MPAs in South-East Asia, as well as the rest of the world, have been reported tofail in a number of different ways; the failure to meet objectives, being listed as a marinereserve but not succeeding in implementing management, or lying dormant at one of thedevelopment stages of an MPA. One of the major reasons for these failures has been arguedto be the lack of long-term funding for the management costs of these parks, which results inthe failure of legal enforcement of the protection of these parks (Svensson et al., 2009). Aspart of an attempt to approach this problem, there has recently been a transformationobservable in the governance of MPAs, with the increasing presence of actors from theprivate sector involved in the governance of MPAs. The private sector, supported throughtourism, can offer a source of revenue. Svensson et al. (2009) argue that this enables MPAsto become self-financing, establishing a „truly successful and economically sustainable MPA,especially in developing countries‟ (Svensson et al., 2009:72). These MPAs are believed tohave been formed due to government failure to satisfy public demand for nature conservation,growing societal interest in biodiversity conservation and the rapidly expanding ecotourismindustry. The Durban Action Plan from the World Parks Congress in 2003, called on theprivate sector to „financially support the strategic expansion of the global network of protectedareas‟ and goes further to state that tourism can provide economic benefits and opportunitiesfor communities and create awareness and greater knowledge the natural heritage of humankind (IUCN, 2003; Svensson, 2009).A particular form of these privately managed MPAs is Entrepreneurial <strong>Marine</strong> Protected Areas(EMPAs). These are commercially-supported MPAs where commercial entities, such as diveresorts for example, are acknowledged as full partners in the planning and management ofMPAs (Colwell, 1997). Hence they provide primary stewardship for these coral resources, aswell as economic benefits. A small number of existing examples can be found in which acombination of private actors, park authorities and NGOs have enclosed a marine area andchannel funding to run conservation activities; Van Phong Bay, Vietnam, which hosts a HotelManaged <strong>Marine</strong> Reserve; Chumbe Island Coral Park, a privately managed MPA inTanzania; Sugud Islands <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> Area in Malaysia managed by a privatemanagement company called Reef Guardian; and Bonaire <strong>Marine</strong> Park managed by an NGOauthority and dive operators in the Dutch Antilles (Dixon et al. 1993; Svensson et al., 2009;Teh et al, 2008; De Groot and Bush, 2010). Colwell (1999) suggests that many EMPAs willultimately evolve into some „form of hybrid MPA with increased partnership among privatestewards, NGOs and governments‟ (Colwell, 1999: 221).Currently the governance of privately managed MPAs, including EMPAs, is still widelyundocumented and insufficiently researched (Svensson et al., 2009). One of the main issuesfor effective MPA implementation is using appropriate governance arrangements to determinerules for the access and inclusion of certain actors (Pomeroy et al., 2010). MPAs come indifferent forms (such as closed areas, no-take reserves, multiple use, and zoning of oceans)and carry different names (such as parks, reserves and sanctuaries). MPAs can be formedthrough different processes; some are formed from the top down, thus by the state, andothers from the bottom up, i.e. by local communities. As a result, a number of differentgovernance modes for MPAs have been applied to date: centralized or decentralized, comanagementor community-based (Jentoft et al., 2007). In EMPA‟s a new group of actors are14

involved, namely entrepreneurs, and thus the governance modes of these types of MPAs willdiffer from those which involve other actors.According to Jameson et al. (2002: 1180) „the usefulness of appropriately sized, wellmanagedMPAs is not in question. What requires closer scrutiny is the institutional andcommunity capacity necessary for effective MPA management to occur‟. Hence, the successor failure of MPAs relies on their design as a governing system. In terms of the governance ofEMPAs, little attention has been given to the challenges associated with EMPA management,the forms of control that are necessary for these EMPAs to gain legitimacy and to functionsuccessfully, and to the different forms EMPAs may take in different settings (De Groot andBush, 2010). Colwell (1999) provides a general framework with the main functions of EMPAsbut he does not explore further into the characteristics of EMPAs, the perils and promiseswhich lie in EMPAs, nor does he provide a set of conditions under which EMPAs can function(De Groot, 2008). This brings forward the question of what the functions and characteristics ofthe entrepreneurs, which is what makes these MPAs different from generic MPAs, in theseEMPAs are, and how they are able to steer the development of EMPAs. How do these actorsgain legitimacy for themselves, and actually create new institutional arrangements to steermarine conservation?The Yayasasn Karang Lestari coral restoration project in Pemuteran, North Bali and themarine tourism park in Gili Trawangan, Lombok are two MPAs which are funded byindividuals from the private sector, and can therefore be presented as EMPAs. What isinteresting about these projects is that both EMPAs make use of Biorock technology and thusappear to be financing some degree of restoration and not just conservation, as would be thecase in an EMPA as defined by Colwell, thereby presenting a new approach to fighting thedegradation of coral reefs. The EMPAs control the access to the reefs through the formulationof guiding principles and the creation of institutions. Furthermore, these EMPAs include anumber of different actors making the governance of the area a complex process with a largespectrum of social interactions, negotiations, conflict and decision-making. Though it is knownthat it was entrepreneurs that initiated these projects, little is known about what makes ordefines an entrepreneurial approach to conservation and restoration, and the outcome of theinstitutional arrangements formed around these new access regimes and controlmechanisms.1.2 ObjectiveThis thesis aims to analyze the potential role of the private sector in creating durableconservation and restoration agreements to protect coral reefs, by investigating the socialprocesses which shaped the EMPA in Pemuteran, North Bali and the EMPA in GiliTrawangan, Lombok.In both cases an individual or group of individuals from the private sector initiated the creationof a MPA in the area in response to the destruction of the reefs, and continue to fund theEMPAs. The two cases also have in common the application of Biorock restorationtechnology which in both places was initially invested in by entrepreneurs. Hence, in bothareas entrepreneurs recognized the need to conserve the area which induced the creation ofNo Take Zones (NTZs), but they also recognized the opportunity to invest in technology torestore coral, thereby adding value to the existing reefs. In these projects entrepreneursvested their own resources into the protection of the coral reefs.What are unknown, with so little research conducted in EMPAs, are the social processeswhich shape EMPAs; the ways in which the private sector is able promote conservation andrestoration in their environment. The development of the EMPAs and the institutionalarrangements through which they are managed at present, are the result of a process ofinteractions between these entrepreneurs and their environments. This process is made evenmore complex with the presence of a large number of different stakeholders which are alsoinvolved in this process. Two „success stories‟ in the Indonesian archipelago will be comparedto analyze these processes. To reach this objective three main questions will be posed.15

A logical opening to the research process is to define what entrepreneurial opportunities werethe starting points for the development of marine conservation in these areas:(1) What were the entrepreneurial opportunities exploited in the two projects, which wererelevant to the development of marine conservation?This descriptive question aims to explore what types of opportunities were directly, orindirectly, responsible for the development of marine conservation and restoration in theseareas. The opportunities and how they contributed to the development of the EMPAs will bedescribed, but also the individuals involved in this process. Who was responsible fordiscovering, evaluating and exploiting these opportunities, and what were their motivations todo so? What is it that makes these individuals entrepreneurs? Why was it these individualswho exploited these opportunities, and not the initial resource owners? Did they have accessto information to identify the opportunity, and the cognitive properties necessary to evaluatethe opportunity? Did they recognize the value that protecting, and adding value to, the reefscould have to their livelihoods? What was their motivation in creating value in these reefs?Once a clear picture of these opportunities and entrepreneurs has been sketched, morespecific questions can be posed regarding how the entrepreneurs were able to exploit theseopportunities and influence their environment. Hence, the following question focuses on theprocess of how the private sector was able to exploit these opportunities, by looking at theinteractions between the private sector and their environment.(2) Through which types of processes were the entrepreneurs able to legitimizethemselves in the eyes of the other actors involved in these EMPAs?This analytical question takes a more critical look at the linkages or relations between theentrepreneurs and the other actors in the network which is the EMPA, and the way that theserelations have been established through the development of the EMPAs. It is important tobegin with indicating the most relevant actors involved in the EMPA and how theentrepreneurs communicate with these. What follows is the question of what interactionshave taken place between the entrepreneurs and their environment resulting in the legitimacyor lack thereof, of the entrepreneurs in the eyes of the other stakeholders: Is there equalparticipation in decision-making in the EMPA? What tools have the entrepreneurs used tobuild up trust amongst the other stakeholders? Are there conflicts between the entrepreneursand the other actors? This process of social negotiation has led to the establishment of acertain level of legitimacy for these entrepreneurs. This in turn has determined the level ofinstitutionalization of the EMPA, which leads to the last question.(3) To what extent has the private sector been able to alter or create institutions aroundmarine conservation in the two cases?This question explores a more material concept of the rules and steering mechanisms thatentrepreneurs have been able to develop through these EMPAs, as well as providing ameasure to determine to what extent they were actually successful in institutionalizing theEMPA: what institutional arrangements and organizations have formed, or altered aroundthese EMPAs? How is the management of the EMPA organized? How are other steeringmechanisms such as economic incentives organized? Are there conflicts or problems aroundgoals in terms of conflicting uses? Are these new arrangements legitimate in the eyes of theother stakeholders? How durable are they? Thus, the reader is left with a clear picture of thecurrent governance arrangements in the two areas, which has been a direct result of thepreviously mentioned social negotiation process.1.3 <strong>Marine</strong> conservation policy in Indonesia: the role of the stateDuring the New Order Period in Indonesia, the years between 1967 and 1998, naturalresource conservation and management was carried out using a centralized approach.National policy stated that all marine waters were state property to be managed centrally,through provincial, regency and village offices of the central government. Democracy wasabsent in Indonesia during this period, also in marine resource management. Accordingly, the16

local government and communities had no significant role in resource management, whilstthe central government had a very strong role (Satria et al., 2006a).At the time there were three main legal products which covered marine conservation policy,which are important to introduce as these laws still apply today, despite shifts inresponsibilities in marine conservation: the Fisheries Law, the Living Natural Resources<strong>Conservation</strong> Law and the Environmental Law. The Fisheries Law was characterized bystate-based fisheries conservation and management, and no articles in this lawacknowledged traditional fishing systems, though many existed. Under the Living NaturalResources <strong>Conservation</strong> Law, the central government could establish wildlife reserves andsanctuaries, and classified Natural <strong>Conservation</strong> Areas (NCAs) into three types: nationalparks, forest parks and natural tourism parks. Management of these areas was under controlof the central government, but could be delegated to individual states or privately controlledgroups. To implement NCA policy the government developed the Technical Executive Officeof the National Park Station and the Agency for Natural Resources <strong>Conservation</strong>, or BalaiKonservasi Sumberdaya Alam (BBKSDA), as a representative of the central government bothin province and regency areas. These agencies were linked to the Ministry of Forestry (MF)and were responsible for monitoring and controlling the NCAs. Finally, the Environmental Lawstated that natural resources, on the mainland as well as in the ocean, were under stateproperty rights and were to be utilized for the people‟s welfare. Article 12 of this law allowedthe central government to transfer some authority to the local government for theimplementation of environmental management, but this transfer of authority was identified asforms of delegation or deconcentration rather that devolution (Satria et al., 2006a).Natural resource management in Indonesia changed dramatically after the fall of presidentSoeharto‟s regime. Since the fall of his regime in 1998, Indonesia experienced a dramatictransferral of power from the central government to the provinces and regencies, oftencollectively referred to as „reformasi‟ (Clifton, 2003). These changes were led by theestablishment of the Local Autonomy Law which states that as far as 12 miles from theshoreline is under provincial government authority, and within those 12 miles the first fourmiles are under the authority of the local or district government. The powers of theseauthorities include (1) exploration, exploitation, conservation and marine resourcemanagement within the authorized marine area, (2) administrative management, (3) zonemanagement, and (4) law enforcement of local regulation and central government regulationsthat have been deconcentrated to the local government (Satria and Matsuda, 2004; Satria etal., 2006b).The second important change for marine conservation came forth in the establishment of theMinistry of <strong>Marine</strong> Affairs and Fisheries (MMAF). The main duty of the MMAF, as identified inthe Presidential Decree No.177/2000, is to assist the president in conducting somegovernmental tasks in the marine and fisheries field, and to handle certain functions such asthe establishment and monitoring of the local autonomy implementation plan in maritime andfisheries fields, and the management and implementation of plans for protection of naturalresources of the seas within the 12 miles (Satria and Matsuda, 2004).There were a number of factors which prevented the local autonomy law from ensuringdecentralization of marine conservation; there was considerable institutional conflict betweenthe MF and MMAF. The MF referred to the Living Natural Resources <strong>Conservation</strong> Law andNational Government Decree which mandated the MF to take responsibility over NCA‟s,whilst the MMAF, established in 1999 after these laws were enacted, claimed that authority ofNCAs in the marine environment should be given to them as marine marks are part of marineecosystems which is essentially their domain. This problem was intensified by the different,even conflicting, approaches the two ministries had toward conservation and preservation ofnatural resources (Satria et al., 2006a).Eventually a new Fisheries Law no. 31/2004 was issued entrusting the MMAF with theauthority to manage <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> Areas (MCAs), including marine reserve areas,marine national parks, marine tourism parks (MTPs) and fisheries sanctuaries, which werepreviously formally under the management of the MF. This change led to the revision of theLiving Natural Resources <strong>Conservation</strong> Law and the National Government Decree, now17

ecognizing the responsibility of the MMAF, removing some of the previously mentionedinstitutional conflicts (Satria et al., 2006a). The MMAF was given the responsibility forconservation of ecosystems, species, and genetic diversity of marine life, and this law hasdramatically accelerated the development of MPAs in Indonesia (Yusri et al., 2009).The transfer of authority over marine conservation areas from the MF to the MMAF hashowever been a lengthy and difficult process. Research presented at the World OceanCongress in 2009 showed that in 2008, the MMAF managed 53% of MPAs in Indonesia,whilst the MF still managed 39%. Furthermore, the MF managed almost twice the area of theMMAF, primarily because the former manages seven large national parks, and the lattermanages mostly small MPAs. The most common type of MPA in Indonesia, with 30 in total, isreferred to as the Locally Managed <strong>Marine</strong> Area (LMMA). The second and third mostcommon are Mangrove <strong>Conservation</strong> Areas, with 28 in total, and MTPs, of which there are18. The number of LMMUs has increased significantly since the issue of Law No. 27/2007which enables district authorities to develop and manage their own MPAs.Local governments have the authority to manage conservation areas in their territory. Thedetails on how a local government is to manage their conservation area is regulated throughthe MMAF. In an effort to accelerate the implementation of the local autonomy law in coastaland marine areas, the MMAF established a technical implementation unit, similar to the MF‟sBKSDA, for the management of coasts, marine areas and small islands: the Institute forAquatic <strong>Conservation</strong> Areas, or Balai Kawasan Konservasi Perairan Nasional (BBKPN),located in Kupang. This unit, inaugurated March 2008, is devoted to manage, utilize andsupervise MCAs in the east of Indonesia (Department of Fisheries Resource Allocation,2009).At the World Oceans Congress held in Manado, May 2009, Indonesia signed a declarationapproving the Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI). „The CTI represents a unique and innovativeinternational collaboration focusing on the conservation and sustainable use of marineresources‟ (Clifton, 2009: 91). Since its announcement in 2007 the CTI has received muchpolitical support and culminated in the Regional Action Plan agreed at the World OceansCongress. Central to this agreement is the establishment of a network of MPAs. TheIndonesian president declared that Indonesia would designate 10 million hectares of MPAsacross the archipelago by 2010 and 20 million hectares by 2020 (Wootliffe, 2009). At presentIndonesia has in fact already over met this commitment.Thus, in recent years there appears to have been significant government effort to increasemarine conservation in Indonesia. Though Indonesia has already designated more than 15million hectares of MPAs, the effectiveness of these is questionable. There are numerousMPAs with unclear boundaries, and even without management plans. Yusri et al. (2009)argue that these problems need to be addressed quickly, because without proper design andmanagement, MPAs cannot meet the marine and coastal conservation needs of Indonesia.Large NGOs like The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and World Wildlife Fund (WWF) have beenclosely involved in the CTI since 2003 and have been recognized as full partners in itsimplementation. Accordingly, the Indonesian government too is working with several of theseglobal NGOs to reach their 2020 CTI targets with effectively managed MPAs, and not just„paper parks‟, which are officially designated conservation parks but lack compliance by theresource users or enforcement by the management agencies (Jameson et al., 2002). TheTNC is currently working on designing an effective management protocol for MPAs. They areworking with the Indonesian government to design a system so that they can run a scorecardprocess to assess whether or not there is effective management in place in an MPA. Thescorecard will produce a level of effective management so that they will be able to map all theMPAs in Indonesia in terms of management effectiveness. This will help distinguish paperparks from ones with effective management systems in place.Furthermore, the TNC is trying to design this so that the system can be used to assess alltypes of conservation areas: „We have tried to design it to be used for any type of MPA, andnot just national parks‟ (personal communication: Senior Advisor Indonesia <strong>Marine</strong> Program:The Nature Conservancy 18/3/2010). TNC, as one of the major NGO collaborators with the18

Indonesian government in the area of marine conservation recognizes the potential for noveltypes of MPAs, including small-scale privately-led MPAs, and aims to design the scorecardsystem so that private actors „should be able to use the same protocol to assess what leveltheir MPA is at in terms of effective management‟ (personal communication: Senior AdvisorIndonesia <strong>Marine</strong> Program TNC 18/3/2010). TNC has already started mapping 9 or 10 placeswhere private actors have been exercising marine conservation, and even suggest that, ifdeemed affective, these should be included in the network of MPAs in Indonesia workingtoward reaching the 2020 CTI goals. Hence, recognition of the potential of these novel typesof MPAs to work toward Indonesia‟s larger goals in marine conservation is growing.This recognition is also visible globally, as research into private sector-led MPAs is slowlybeginning to appear in academic literature. The following section will discuss what has beendone so far in terms of research into these novel MPAs in which the private sector plays aleading role.1.4 Private sector involvement in marine conservation: what is known?Private terrestrial reserves have existed for centuries, but only in the last 50 years have theybeen accepted as a conservation tool (Svensson et al., 2009). There are numerous privatelyowned and managed terrestrial areas all over the world which protect biologically significanthabitat. In South Africa alone more than half of the protected areas are under private control.In the Netherlands, Stichting Natuurmonumenten, a large Dutch NGO, owns wetlands as wellas cultural heritage sites that it keeps under protected management and the TNC has boughtup large amounts of land in the United States with endangered resources and manages theseprivately (Riedmiller and Carter, 2000). Rocliffe (2010) argues that comparatively there hasbeen little interest in privately-led marine parks because it was always assumed that oceansare commons and can thus not be owned or leased the way terrestrial parks can.Interestingly, commercial enterprises have actually been acquiring rights to submerged landsfor many years. This submerged land is owned or leased for oil extraction, dock construction,marina construction, aquaculture and fisheries to name a few. However, leasing submergedlands as a tool for marine conservation has not been as common despite the fact that the costof leasing such areas is generally lower than for equivalent schemes on terrestrial land(Svensson et al., 2009). An increasing number of NGOs are interested in this idea, and TNCis currently looking at the conservation potential for attaining rights of submerged lands inIndonesia (personal communication: Leader Coral Triangle Program WWF 12/3/2010; personalcommunication: Senior Advisor Indonesia <strong>Marine</strong> Program TNC 18/3/2010).Currently a growing number of commercial enterprises such as hotels are also discoveringthe marine conservation potential of these legal mechanisms and are leasing or assumingquasi-tenure over coastal areas to protect these (Rocliffe, 2010). Svensson et al. (2009)present an example in Fiji where the Navina Island resort has taken advantage of thecustomary practice of owned limited access areas of the sea and its resources called „tabu‟areas. The sea around an island is leased up to a depth of 30m and a monthly fee is paid tothe owners who enforce fishing restrictions, and the resort follows the tabu rules whichprohibit damaging the coral reef or extracting resources.There are also an increasing number of cases in which hotels or dive operators which havethe financial backing, resources and economic incentive have taken over the day-to-daymanagement of MPAs from the government. These areas are usually officially designatedMPAs, but lack the resources to effectively manage the MPA. This handover can be done forpart of total management, such as day-to-day enforcement, but can also take shape in acomplete handover of responsibilities to private enterprises. Colwell (1999) reviewed anumber of cases of private initiatives in coral reef conservation in Honduras and thePhilippines and introduced the notion of entrepreneurial MPAs.Colwell (1997) argues that though EMPAs do not provide the large-scale protection neededglobally, EMPAs perform several valuable functions; they can protect discrete areas whichserve as a refuge for threatened marine life, they can build local capacity in MPAmanagement, build public awareness for marine conservation and support of MPAs, and19

provide the core areas for larger and slower developing MPAs. Though these MPAs maysuffer because they are created with less research and planning than is generallyrecommended for the more traditional NGO or state-led MPAs, the main advantage for theseMPAs is that they can use existing commercial infrastructure and management structures sothat these MPAs can be created more quickly and management regimes can be institutedmore easily than is possible with large-scale MPAs. The ultimate goal of Colwell‟s approach isto create a network of small locally-run MPAs which use tourism or other commercial supportto achieve long term economic and environmental sustainability - a situation whereeconomics and ecology are combined.Colwell (1999) provides a brief classification for EMPAs, outlining several criteria for success,as well as several limitations. He argues that EMPAs are most appropriate where thegovernment or local community is unable or chooses not to manage local marine resources.In their place hotels or dive operators act as the primary stewards of these areas.Furthermore, these private sector members must be able to enforce restrictions on resourceuse. This requires the delegation of marine tenure or the right to control resource byprevailing authorities to these non-state organizations (De Groot and Bush, 2010). At thesame time, Colwell illustrates some level of skepticism as to the role of private initiatives inconservation; he states that due to the nature of a commercial entity, with profit as theprimary motive and the fact that it does not answer to a public constituency, the potential forthe abuse of power is high. Thus, Colwell (1999) argues for the need for external reviews ofEMPA managers.Colwell (1999) also presents two conflicting contextual criteria for the success of EMPAs.EMPAs appear to work best in relatively isolated areas where there are fewer potentialconflicting uses of the marine resources by other stakeholders, and thus there is little existingenforcement of regulations or restrictions. This can be attributed to the fact that, similar totraditional MPAs, EMPAs are not likely to be sustainable without substantial input from all keystakeholders in defining issues, selecting management strategies and implementingmanagement measures. Thus, these private actors must acknowledge the rights of otherstakeholders and accommodate their needs (Colwell, 1999). With existing institutions aroundmarine conservation, the private sector must then also build consensus and gain the supportof local state and customary authorities. The second, somewhat conflicting criterion is thatEMPAs must be relatively accessible to attract the clientele necessary to offset the costs ofmanaging the EMPA. Revenues from in and around these areas may be used to fundEMPAs: user fees, accommodation charges, tour guide services, royalties, research charges,restaurant charges and private donations (Riedmiller and Carter, 2000).A last important point that Colwell brought forward is that the ongoing success of EMPAsrequires institutional protection for investors. He suggests that if management is taken overby the government or another body, the initial investors should be compensated somehow,and that without this institutional security the likelihood of investments in infrastructure will beminimal (Colwell, 1999). Traditionally this oversight has been provided by the state. However,as argued by De Groot and Bush (2010) as industries such as recreational diving havebecome global in nature, more networked forms of oversight and control have also becomepossible.Since Colwell‟s introduction to the concept of EMPAs, there have been numerous studies intothese novel MPAs. Some of these studies have brought forward several differentmanagement forms which these EMPAs can take on:20

Table 1: Existing EMPAsName Location Size (ha) Management/ownership structureChumbe Island Coral Tanzania 30 Private management authority; wholly private with a 10Parkyear renewable lease from the governmentSugud Islands <strong>Marine</strong><strong>Conservation</strong> AreaMalaysia 46,700 Private (non-profit) management authority; wholly ownedby Langkayan Island Dive ResortWakatobi Diver Resort Indonesia 200 with Private management authority: informal agreement with500 buffer governmentMisool Eco Resort NoTake ZoneIndonesia 20,000 Private management authority; wholly private with 25 yearlease from local land ownersWhale Island Bay Vietnam 16 Hotel managed marine reserve; wholly private with thearea leased from governmentBonaire National <strong>Marine</strong>ParkDutch Antilles 2,700 Private (non-profit) authority; national park status since1999(Source: Riedmiller and Carter, 2000; Svensson et al, 2009; Rocliffe, 2010; Heinrichs, 2008;Tel et al., 2008; Dixon etal., 1993; STINAPA, 2010)The majority of existing research into EMPAs has looked at the ecological impact of theseforms of protection, staying predominantly within the sphere of the natural environment.Svensson et al. (2009), in their study of Whale Island Resort in Vietnam, claim that theirfindings provide good evidence that Hotel Managed <strong>Marine</strong> Resorts (HMMRs), a specific formof EMPAs, can increase fish stocks rapidly, matching, or in some cases surpassing officiallyestablished MPAs of a similar size. Dixon et al. (1993) in their study of the Bonaire <strong>Marine</strong>Park bring economics into the discussion of EMPAs and assess the trade-offs betweenmarine protection and direct use of an EMPA for tourism. They find that proper EMPAmanagement can yield ecological as well as development benefits, but questions ofecosystem carrying capacity and government retention of revenues raise issues for long termsustainability.Teh et al. (2008) in their case study of Sugud Island <strong>Marine</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> Area in Malaysia,discuss the shortcomings and advantages of private management in operating an MPA tomeet conservation objectives. Though the research is ecologically-oriented, they concludesome success factors for effective EMPA management. Some of these are interesting in theirconformity to Colwell‟s contextual criteria for successful EMPAs. Like in traditional MPAs,buy-in and support from local inhabitants is essential to minimize the potential for socialconflict in these EMPAs. Particularly support from local fishing communities is key, and Teh etal. (2008) emphasize that alienation of fishing communities from marine parks has led toviolent confrontations between fishers and enforcement officials in the past. This strengthensColwell‟s claim that the fewer conflicting uses, the easier it is for an EMPA to develop andfunction. At the same time, the research supports Colwell‟s conflicting claim that EMPAsshould be located in areas which attract clientele to support the costs of management of theEMPA, as Teh et al. (2008) emphasize the importance of the availability of long term funding,the bulk of which comes from private sources.Another interesting point made by Teh et al. (2008), is their suggestion that „dive resorts thatengage in conservation should consider separating business from conservation to avoidpotential conflicts between differing interests‟ (Teh et al., 2008: 3075). In this particular EMPAconservation management is separate from the dive resort and it is argued that a distinctmanagement body is better able to exercise objective judgment in implementing conservationinterests. Furthermore, the management body is obliged to maintain environmental standardsaccording to measures enforced the state, and this body‟s accountability to the stategovernmentthus „acts as a check against situations where conservation objectives may becompromised for business interests‟ (Teh et al., 2008: 3073). This reflects Colwell‟spreviously mentioned skepticism of the ability of the private sector to exercise conservationdue to their overarching profit-seeking motives. This suggests that the inherent commercialnature of private sector may be a significant limitation to their involvement in MPAs.Riedmiller and Carter (2000) delve deeper into some social aspects of by privately-led MPAsin their research into the political challenges of private sector management of MPAs. Theypresent some very interesting conclusions in a study of Chumbe Island National Park,Tanzania. They suggest that the success of privately-led MPAs largely depends on theirpolitical environment. They argue that the definition of boundaries and the implementation of21

certain legislation such as the prohibition of dynamite fishing go far beyond the capacity ofprivate owners, and require a committed governmental and institutional framework, therebyunderlining a limitation of the private sector in exercising marine conservation throughEMPAs. „There are subject matters where private owners (or conservation projects) shouldpursue their interests by lobbying for more favorable government policies that will safeguardtheir effective operation‟ (Riedmiller and Carter, 2000: 149). Furthermore, they argue it is upto the state to create appropriate institutional structures and appropriate legislation, and thatthere must be commitment between governments and private investors if privatemanagement of MPAs is to succeed. These findings are interesting as they underline theremaining important role of the state within these novel types of MPAs, as well as bringingforward the need for cooperation between the private sector and state.Alternatively, De Groot and Bush (2010), in a more recent investigation of EMPAestablishment by dive operators and resorts on Curacao, have shown that these privateactors are not necessarily dependent on state support or ownership of the reef to ensurecompliance to regulations. Their research shows that non-state market driven governancesystems have provided conditions to ensure compliance which is based on development ofcompany based standards.This research has also placed a new light on certain aspects of Colwell‟s classification ofEMPAs: De Groot and Bush (2010) introduce a regulatory function that EMPAs can perform,a function untouched in Colwell‟s classification. In the EMPA on Curacao, „regulations can beenforced through a system based on regulation of diver behavior where there are financialconsequences for violating the rules, and restriction of access‟ (De Groot, 2008). The twocases on Curacao show the potential for regulating diver behavior which opens up a new typeof EMPA management which moves beyond area-based control. „This shift to behavior-basedregulation extends the spatial extent of EMPA beyond house reefs to a wider coral reef area,because all dive sites that are visited also fall under some form of protection‟ (De Groot andBush, 2010: 8). This research introduces the notion that private sector involvement in marineconservation does not have to be highly areal in nature, as suggested in Colwell‟s initialclassification. This approach may develop into wider networks of protection which connect theconservation of coral reef dive sites and the authors argue that a focus on behavior thus maymake Colwell‟s approach more viable, and perhaps provide the basis for larger, slowerdeveloping MPAs in areas that have high tourism value and use.De Groot and Bush (2010) also present some potential limitations to the establishment ofEMPAs. On this island, particularly the risks of market competition within the dive industrylimit the development of EMPAs. Dive operators are on the one hand under pressure tomodulate their activities to ensure less damage to the reefs based on standards set by globaldiving governing bodies, and on the other hand face pressure from customers, who demand aspecific quality from their dive experiences. The market competition that dive consumersprovoke can potentially lead to situations in which operators maximize their returns onincreasingly marginal entrepreneurial conservation-based activities, which consequentiallydeters development of effective marine conservation (De Groot and Bush, 2010). In this caseconsumers play a primary role in granting market-based legitimacy, but the potentialunfavorable situations which could arise emphasize the need for external oversight on privatesector activities. Again, this brings in the seeming need, or dependence on outside, be it stateor non-state, actors within private sector management of MPAs.As mentioned previously, large NGOs have also started to show interest in this form of MPAs.TNC has been doing studies into private MPAs and marine conservation agreements, andhave found that the common thread of the successful ones they have encountered globally isthe individuals who are passionate about these projects and have the drive to work hard tomake them work. They suggest that it is those charismatic „mega individuals‟ who hold thesethings together and drive their developments (personal communication: Senior AdvisorIndonesia <strong>Marine</strong> Program TNC 18/3/2010).There has clearly been some movement in terms of research into the challenges andpossibilities posed by private sector management of MPAs in the last years. However theseresearch efforts remain relatively scarce and underdeveloped when compared to research22

feasible new strategies and institutions can be designed, which better protect theenvironment. Thus, this thesis aims to build on this theory by analyzing the transformationswhich took place in two distinct cases of sever coral degradation in Indonesia. Furthermore,recently the phenomenon of entrepreneurship has been observed in new contexts, andwriters have asserted how entrepreneurship can serve as a central force in the developmentof an ecologically sustainable society. This research aims to build on this by determining therole of these entrepreneurs in marine conservation by studying case studies whereentrepreneurs appeared to play an integral role in marine conservation.1.5.2 Case selection: research sitesAs mentioned previously, this research is site-specific. Hence, the selection of the cases isvery important for the validity of the research. The EMPAs selected are both located inIndonesia, one of the countries in the Coral Triangle. The first case is located in Pemuteran,North Bali, and the second in Gili Trawangan, Lombok.These two EMPAs were strategically selected for four main factors which they have incommon. First and foremost, they are both EMPAs, using Colwell‟s understanding of theconcept; they are exemplary cases of MPAs which have been initiated and are funded by theprivate sector, particularly the dive industry. Secondly, they are both located within the CoralTriangle, an area which has received increasing publicity in recent years and beenrecognized as a biodiversity „hotspot‟:Figure 1: Coral Triangle Region (source: http://www.worldwildlife.org)The perceived need for intensification of protection of this area has resulted in policiesfavoring the establishment of networks of MPAs (Clifton, 2009). This places the two cases ina very relevant area for studying the emergence of novel forms of MPAs. Furthermore, thetwo sites are both dive tourism destinations in Indonesia; the main industry practiced isidentical, and they are located in the same nation. Hence these private sector-led marineconservation initiatives are faced with similar national laws and regulations.24

Figure 2: Map of case study sites (source: http://maps.google.com/)Finally, both sites apply Biorock coral restoration technology within the EMPAs. Additionally, itis interesting that the EMPA in Gili Trawangan directly followed Pemuteran in its application ofBiorock technology.At the same time, it is important to note that the sites do display different socio-economic andecological features, which alters the context in which the EMPAs have been formed.Naturally, this amplifies the variation in the data obtained about the role of the private sectorin the two EMPAs. However, the fact that multiple cases are used does provide a „toughertest‟ in that it can help specify whether the role of private actors in EMPAs is similar despitethe existence of different conditions. Hence it can help specify the different conditions underwhich a theory may or may not hold (De Vaus, 2001).1.5.3 Data collection: sources and methodsThe research was carried out over a period of seven and a half months. The first two monthswere devoted to literature research and proposal writing. During this time, based on theinformation available in the literature and e-mail contact with the managers in the two casestudies, a rough estimate of the key stakeholder types which should be interviewed wasmade. The data collection process in Bali and Lombok took two months in total. Fortunatelythere was not much extra time needed for adjustment to the environment and so forth, sincethe researcher was familiar with the language and the areas of research. Roughly threeweeks were spent at each case study location. The two additional weeks in Southern Bali,were used to organize and conduct interviews with NGOs which were all located there. Thelast three and a half months of the thesis consisted of data analysis and writing.Interviews at both case study locations were sought with dive industry representatives, villagerepresentatives, fishermen representatives, Biorock representatives, governmentrepresentatives and representatives of NGOs working in the case study locations. Purposivesampling was initially used to approach the key stakeholders which were found beforehandmainly through previous reports and studies on the projects found on the internet, andthrough e-mail contact with the co-founder of the Yayasan Karang Lestari in Pemuteran andthe Gili Eco Trust (GET) manager in Gili Trawangan. However, the rest of the actors involvedin the EMPA were found through snowball sampling: the first interviewees were asked whoelse would provide useful sources of information. The larger NGOs which were interviewedlater in South Bali were also found through interviewees in Pemuteran and Gili Trawangan.A total of 17 interviews were carried out with stakeholders in the EMPA in Pemuteran, and 16in Gili Trawangan. After the case studies were concluded interviews were conducted withthree NGOs; representatives from Reef Check Indonesia, the WWF and TNC. Reef CheckIndonesia is national NGO, and independent from Reef Check International, but shares thesame vision and mission as its mother organization. This NGO has done a fair share ofresearch in North Bali and aims to create a network of LLMAs, which Pemuteran couldpotentially be in. TNC has recently done research in the marine conservation agreement25

which exists in Gili Trawangan. The interviewee from the WWF did not have any experienceor direct connection to the two case studies, but as the leader for the Coral Triangle Programshe was expected to have an interesting take on EMPAs.All the interviews with the stakeholders in the case studies were semi-structured. A fixed setof topics was addressed for every stakeholder, which lead into different directions, and wentinto differing levels of depth, depending on the interviewee. Questions were prepared, butonly used when interviewees needed encouragement. The general topics covered were: (1)the origins of the EMPA and the role of the entrepreneurs in this (2) the rules around fishingand how these changed (3) their opinion on the value of Biorock for the area (4)communication and relations the interviewed stakeholder had with the other actors,particularly the private actors, and (5) support for the EMPA from the different stakeholders.All the interviews were carried out face-to-face. Two-thirds of the interviews were carried outin English, with the remaining 12 carried out in Indonesian. The first three interviews inIndonesian were carried with the Biorock manager in Pemuteran functioning as theinterpreter. The remaining interviews were conducted without a translator. The majority,namely 95%, of the interviews were recorded, with only two actors objecting to this.Transcripts were made within a day or two after each interview. One of the key stakeholdersin Gili Trawangan, namely a representative for the fishing community could not beinterviewed, so transcripts from a previously held interview conducted by a student from theUniversity of Sydney was used to gain the perspective of this particular stakeholder group.Although the interviews were the main data collection tool for the research, participantobservation was important to complement the interviews to study the social and physicalsetting of the environment, and internalized notions of norms, traditions, roles and values.The researcher spent roughly three weeks at each case study location making field notes ofevents and interesting behaviors which were thought relevant to the research and interactingwith the research population provided a large amount of data. In Pemuteran the researcherspent most of the time aside from the interviews at the Biorock Centre on the beach,observing the interaction of all the different actors set at the beach, spending time with theoperators whilst they carried out their day-to-day jobs, and studying the Biorock structures.Furthermore, a glass-bottom boat tour for a tourist who joined the “Adopt a Baby Coral”program was joined, to gain a sense of how the Biorock Centre provides for tourists. In GiliTrawangan a GET meeting was attended, and the researcher joined the GET manager insome informal meetings with different stakeholders in the EMPA. Furthermore, the researcherhelped out with the building and consequent sinking of a Biorock structure which provided apoignant example of how the dive community interacts.Lastly, the review of documents provided some supporting information, particularly detailswhich were overseen or unknown by the interviewees. Documentaries, newspaper articles,student reports, pamphlets, and contracts were reviewed for details which were not obtainedin the interviews. Secondary literature in the form of previous case studies of the areas andliterature reviews on marine conservation policy in Indonesia were particularly useful increating a history of the development of the EMPAs.1.5.4 LimitationsThis method of research displayed some limitations and challenges. Firstly, it must be notedthat three weeks is quite a short period of time to conduct a case study, and it is difficult todetermine whether more in-depth information would have been collected had the researcherstayed longer. Furthermore, longer time in the field may have enabled the researcher to buildup more trust amongst the interviewees, thereby increasing the information they may haveshared.Carrying out research in Indonesia provided a large challenge for the researcher, despitebeing familiar with the culture and language. Initially the interviews in Indonesian were carriedout with an interpreter, through which some information is likely to have been lost intranslation. Later the Indonesian language interviews were carried out by myself, but becauseI speak the language at a moderate level, it is likely that much information was lost in this waytoo. Aside from the language, conducting research in a particularly bureaucratic country likeIndonesia made it very difficult to make contact with government representatives.26

Unfortunately, no regional level government representatives could be interviewed, inducingthe need to obtain information on government involvement from other sources.Furthermore, being a foreigner made it difficult at times to establish trust and gain thecooperation of some of the locals, particularly in a place like Gili Trawangan where the localstakeholders have become quite used to being interviewed and may suffer from researchfatigue. As mentioned previously, one of the critical stakeholders in Gili Trawangan could notbe interviewed, and a different researcher‟s information had to be used to fill the gap in theresearch. Another large challenge as a foreigner research in terms of internal validity lies intrying to obtain open responses to overt sociological research such as this where therespondents may have a vested interest in directing their answers in certain directions.Despite these challenges, a large amount and variety of empirical data was obtained duringthe two case studies, with perspectives from all the important stakeholder groups covered.This was used to form a picture of the role of the private sector in the development of theEMPA in Pemuteran and Gili Trawangan, which will be presented in chapters 3 and 4respectively.1.6 Outline of thesisThis thesis aims to analyze the role of the private sector in creating durable conservation andrestoration agreements for the protection of coral reefs. Chapter two presents the analyticalframework, with a description of supporting theories, which will be used to carry out thisanalysis. Chapter three and four form the centre of the thesis. These chapters presentanalyses of the role of the private sector in the two cases; Pemuteran in chapter three, andGili Trawangan in chapter 4. These case studies will be analyzed using the three mainconcepts comprising the analytical framework. In chapter five the two cases will then becompared, and the role of the potential role of private sector in creating durable agreementsin EMPAs, and consequentially their role in the bigger movement of marine conservation willbe discussed, as well as the value of the analytical framework used. Finally, chapter six willdraw the thesis to a close by answering the research questions with some conclusivestatements and recommendations brought forward by the research.27

2 Theoretical Framework2.1 IntroductionThe objective of this chapter is to build an analytical framework capable of analyzing the roleof the private sector in marine governance, particularly through creating conservation andrestoration agreements to protect coral reefs in EMPAs. An ecological modernizationapproach is proposed to meet this objective. This theory addresses how ecological rationalityhas been brought into the economic process, which has led to new institutionalarrangements. Furthermore, environmental problems are seen as manageable issues, to bemanaged by not only the state, but by a wide range of non-state stakeholders. Thus, itprovides an ideal basis for sociological analysis of the phenomena studied in this thesis,where a novel set of private actors is approaching an environmental problem which has notyet been solved by the state. First ecological modernization theory will briefly be described inits broader context, pointing out the themes most relevant to this analysis. The next stepnarrows down the scope of analysis, using ecological and political modernization theory topresent a description of shifts in ocean and coastal governance and how this is relevant tomarine conservation in Indonesia, underlining the emergence of the private sector, orentrepreneurs, in ocean and coastal governance. This is followed by an overview ofentrepreneurialism as an emerging field of research, highlighting what concepts exist whichcould be used to assess the nature of entrepreneurship in EMPAs. Theory on social capitalwill then be explored, underlining how entrepreneurs can use this concept to overcomeproblems of collective action. As a last component of the framework some basic theory oninstitutionalization will be discussed to determine how to analyze the extent to which theprivate sector was able to institutionalize their ecological aims in economic practices. Finally,an analytical framework using the relevant concepts from the theory explored will be defined.2.2 Ecological modernizationFrom the mid 1980s onward several lines of sociological and political science analyses onenvironmental problems and reforms converged into a more or less coherent perspectivecommonly known as ecological modernization. This perspective was originally developed inorder to understand the changes that were taking place at the time in the institutions andsocial practices involved in environmental deterioration and reform in Germany, theNetherlands and Denmark. This perspective recognizes that modern institutions and practicescould no longer be viewed solely in terms of their detrimental, all pervasive influence on theenvironment, which was the dominant view in most sociological analyses of the 1970s and1980s. Instead, the ecological modernization perspective looks at how environmentalinterests and considerations are starting to make a difference with respect to the organizationof modern society (Mol and Spaargaren, 2002).The process of environmental reform is given shape by the actions undertaken by varioussocietal actors, and ecological modernization theory contributes to the understanding of theseactions and processes by providing concepts which aid in understanding these developments(Van Den Burg, 2006). Mol and Spaargaren (2002) summarize: through all kinds ofmechanisms, interest groups and social processes and dynamics, environmentalconsiderations are beginning to transform the processes of production and consumption, andthe institutions which are linked to that. Hence, modern society is experiencing shiftingrationalities, which lead to societal action, which consequentially result in environmentalreform. Furthermore, ecological modernization recognizes existing realities and furtherpossibilities to transform the current institutional order into one that takes environmentalconsiderations into account. Thus ecological modernization focuses on relative innovations,as opposed to revolutionary change, and sees merit in working within the system. Byanalyzing contemporary transformations feasible new strategies and institutions can bedesigned in the future, which better protect the environment.This thesis contributes to this by analyzing private sector involvement in marine governancethrough a new emerging governance arrangement, namely EMPAs. The environmental28