Obstetric Fistula and Inequities in Maternal Health - UNFPA

Obstetric Fistula and Inequities in Maternal Health - UNFPA

Obstetric Fistula and Inequities in Maternal Health - UNFPA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

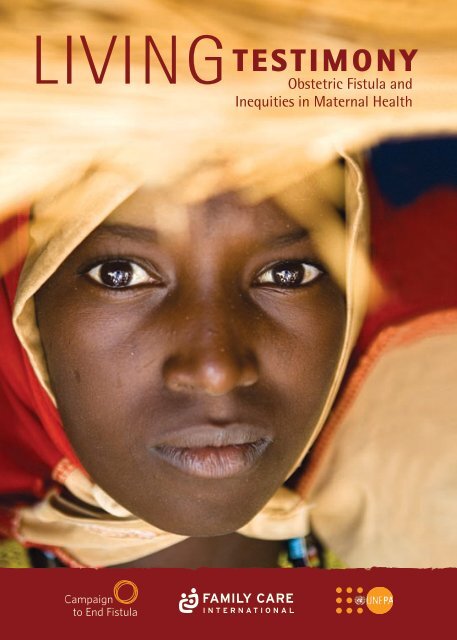

Liv<strong>in</strong>g T e s t i m o n y<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong>

L i v i n g T e s t i m o n y<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong>Photo credit: Lucian Read/WpN/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong>

AcknowledgementsThis publication was prepared by Family Care International (FCI) <strong>in</strong> collaboration withthe United Nations Population Fund (<strong>UNFPA</strong>).The contributions of the follow<strong>in</strong>g are gratefully acknowledged:Author: Debra A. Jones, FCIFCI Contributors: Ellen Brazier, Shafia Rashid, Ann Starrs, <strong>and</strong> Elizabeth Westley<strong>UNFPA</strong> Contributors: Kate Ramsey, Yahya Kane, Ann Pettigrew Nunes, Arletty P<strong>in</strong>el,Anjali Kaur, Saira Stewart, Julie Weber, Lydiah Kemunto Bosire,<strong>and</strong> Larisa JacobsonOther Contributors: Petr<strong>in</strong>a Lee PoyProduction Management: Adrienne Atiles, Luz Barbosa <strong>and</strong> Virg<strong>in</strong>ia TaddoniDesign <strong>and</strong> Layout: Green Communication Design <strong>in</strong>c., Montreal, CanadaProofread<strong>in</strong>g: Adrienne Atiles, Brian Jones, <strong>and</strong> Séver<strong>in</strong>e Origny-FleishmanTranslation: Antler Translation Services, Inc., <strong>and</strong> Séver<strong>in</strong>e Origny-FleishmanPhotographs: <strong>UNFPA</strong> <strong>and</strong> Campaign to End <strong>Fistula</strong>S<strong>in</strong>cere gratitude also goes to the numerous <strong>UNFPA</strong> colleagues <strong>in</strong> the Country Offices,Country Support Teams <strong>and</strong> Technical Staff at <strong>UNFPA</strong> Headquarters, <strong>Fistula</strong> Work<strong>in</strong>gGroup, TSD Publication Review Committee, <strong>and</strong> <strong>UNFPA</strong> partners for country assessmentsfrom Bangladesh, Ben<strong>in</strong>, Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic,Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>ea, Eritrea,Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Rw<strong>and</strong>a,Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, Timor Leste, Ug<strong>and</strong>a, <strong>and</strong> Zambia.© 2007 <strong>UNFPA</strong> <strong>and</strong> Family Care International, Inc.To order additional copies or to convey questions or comments, please contact:publications@fcimail.org or fistulacampaign@unfpa.orgFor further <strong>in</strong>formation, please visit the follow<strong>in</strong>g Websites:www.familycare<strong>in</strong>tl.orgwww.unfpa.orgwww.End<strong>Fistula</strong>.org

Table of ContentsForeWORDExecutive Summary 1Introduction 3<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> 6Perspectives on <strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong> 7Life with <strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> 7Life after <strong>Fistula</strong> Treatment 8Family Members of Women Liv<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> 9Voices from the Community 11Traditional Birth Attendants 12<strong>Health</strong> Care Providers 13The Context <strong>in</strong> Which <strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> Occurs 14Social <strong>and</strong> Cultural Context 14Political <strong>and</strong> Economic Situation 15Select Country Assessments: Key F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs 17Bangladesh 17Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso 18Cameroon 20Democratic Republic of Congo 21Eritrea 22Sudan 23Promis<strong>in</strong>g Practices 26Eritrea: Re<strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>and</strong> Counsell<strong>in</strong>g 26Ethiopia: Model <strong>Fistula</strong> Hospital 26Malawi: Community Empowerment to Strengthen <strong>Health</strong> Care Provision 26Niger: Social Rehabilitation <strong>and</strong> Re<strong>in</strong>tegration 27Sudan: Midwifery School System 27<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong>: Strategic Recommendations 28Conclusions 31Endnotes 32Needs Assessment ReportsFigures <strong>and</strong> SidebarsIv<strong>in</strong>side back coverGlobal Advocacy for Safe Motherhood<strong>in</strong>side front coverMap of Campaign to End <strong>Fistula</strong> 3Illustration of <strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> 6Three Delays 8Female Genital Mutilation/Cutt<strong>in</strong>g 12

ForewordWomen who have endured an obstetric fistula are liv<strong>in</strong>g testimony to the challenges of maternal health.Hear<strong>in</strong>g their stories helps us to underst<strong>and</strong> how to address these challenges more effectively.The persistence of fistula is an unacceptable rem<strong>in</strong>der of the enormous <strong>in</strong>equities between rich <strong>and</strong> poornations, <strong>and</strong> between rich <strong>and</strong> poor women with<strong>in</strong> nations, <strong>in</strong> access to <strong>and</strong> quality of reproductive healthcare. <strong>Fistula</strong> reveals how poverty <strong>and</strong> gender <strong>in</strong>equality limit women’s exercise of their reproductive rights.Complications related to pregnancy <strong>and</strong> childbirth are among the lead<strong>in</strong>g causes of death <strong>and</strong> disability forwomen of reproductive age <strong>in</strong> many parts of the develop<strong>in</strong>g world. More than half a million women diefrom pregnancy-related complications each year. Furthermore, an estimated 210 million women are leftwith disabilities, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g obstetric fistula—perhaps the most severe childbirth-related <strong>in</strong>jury due to itsdevastat<strong>in</strong>g mix of medical, social, <strong>and</strong> psychological consequences.This publication explores knowledge, attitudes, <strong>and</strong> perspectives on pregnancy, delivery, <strong>and</strong> fistula from31 country-level needs assessments conducted <strong>in</strong> 29 countries <strong>in</strong> the Campaign to End <strong>Fistula</strong> (see <strong>in</strong>sideback cover for the complete list). Experiences of women liv<strong>in</strong>g with obstetric fistula, their families, communitymembers, <strong>and</strong> health care providers are brought to light. This <strong>in</strong>formation represents important research onthe social, cultural, political, <strong>and</strong> economic dimensions of obstetric fistula, draw<strong>in</strong>g attention to the factorsunderly<strong>in</strong>g maternal death <strong>and</strong> disability.We hope this publication will serve as an advocacy tool to strengthen exist<strong>in</strong>g programmes <strong>and</strong> encouragefurther research on how to <strong>in</strong>crease access to vital maternal health services, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g fistula prevention <strong>and</strong>treatment. We implore policy makers, programmers, <strong>and</strong> researchers to listen to these women’s voices <strong>and</strong>consider the promis<strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>and</strong> strategic recommendations described here<strong>in</strong>.What we have learned so far can help po<strong>in</strong>t the way, but much more still needs to be done. We cannotafford to wait—the costs to women, communities, <strong>and</strong> health systems are simply too great to delay action.Too many of the world’s most disadvantaged <strong>and</strong> vulnerable women have suffered this preventable <strong>and</strong>treatable condition <strong>in</strong> silence. Too many women are dy<strong>in</strong>g unnecessarily <strong>in</strong> childbirth. It is time to put anend to the <strong>in</strong>justice of fistula <strong>and</strong> maternal death.Thoraya Ahmed ObaidExecutive DirectorUnited Nations Population Fund <strong>UNFPA</strong>, theUnited Nations Population Fund, is an <strong>in</strong>ternationaldevelopment agency that promotes the right of everywoman, man, <strong>and</strong> child to enjoy a life of health <strong>and</strong>equal opportunity. <strong>UNFPA</strong> supports countries <strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>gpopulation data for policies <strong>and</strong> programmes to reducepoverty <strong>and</strong> to ensure that every pregnancy is wanted,every birth is safe, every young person is free of HIV/AIDS,<strong>and</strong> every girl <strong>and</strong> woman is treated with dignity <strong>and</strong>respect. <strong>UNFPA</strong> <strong>and</strong> its partners launched the globalCampaign to End <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2003.Jill W. SheffieldPresidentFamily Care International The mission of Family CareInternational (FCI) is to ensure that women <strong>and</strong>adolescents have access to the high-quality <strong>in</strong>formation<strong>and</strong> services they need to improve their sexual <strong>and</strong>reproductive health, experience safe pregnancy <strong>and</strong>childbirth, <strong>and</strong> avoid unwanted pregnancy <strong>and</strong> HIV<strong>in</strong>fection. For more than 16 years, FCI served as thesecretariat of the Safe Motherhood Inter-Agency Group<strong>and</strong> currently serves as co-chair of the Partnership for<strong>Maternal</strong>, Newborn <strong>and</strong> Child <strong>Health</strong>.IVLiv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony

Executive SummaryHere I am sitt<strong>in</strong>g wait<strong>in</strong>g for God to dowhatever he wants to do with me.…I stay quiet <strong>and</strong> do not say anyth<strong>in</strong>g.People offered to lend my husb<strong>and</strong>money so that I could get treated. Herefused, say<strong>in</strong>g that he has other wives.Inspired by the many dedicated <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>stitutions work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> this area, the Campaignseeks to elim<strong>in</strong>ate obstetric fistula while rais<strong>in</strong>gawareness about gaps <strong>in</strong> maternal health services<strong>and</strong> gender <strong>in</strong>equities that <strong>in</strong>hibit the exercise ofwomen’s rights. By late 2006, more than 40 countries<strong>in</strong> Africa, the Arab states, <strong>and</strong> Asia were part of theCampaign to prevent fistula, treat affected women,<strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>tegrate women post-surgery.40-year-old Bissa woman,Burk<strong>in</strong>a FasoThe death or disability of a girl or woman due tocomplications dur<strong>in</strong>g childbirth is avoidable <strong>and</strong>unjust. More than 2 million women liv<strong>in</strong>g withobstetric fistula provide liv<strong>in</strong>g testimony to this<strong>in</strong>justice. The existence of this condition revealssocietal <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional neglect of women. 2Women liv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula are the survivors, yettheir lives are devastated <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> most cases theirvoices have been silenced.Caused by obstructed or prolonged labour withoutskilled medical care, obstetric fistula results <strong>in</strong>serious physical as well as psychological effects.The newborn usually does not survive the trauma.Despite its devastat<strong>in</strong>g medical <strong>and</strong> social impact,obstetric fistula is not a public health priority.Women cont<strong>in</strong>ue to suffer <strong>in</strong> silence <strong>and</strong> isolationeven though obstetric fistula is preventable <strong>and</strong>treatable, even <strong>in</strong> resource-poor sett<strong>in</strong>gs. Stateshave an obligation to provide adequate preventivecare dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy <strong>and</strong> childbirth, fistulatreatment, <strong>and</strong> rehabilitative support.In 2002, <strong>UNFPA</strong> <strong>and</strong> Engender<strong>Health</strong> gatheredgroundbreak<strong>in</strong>g data on obstetric fistula <strong>in</strong> n<strong>in</strong>ecountries <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa. These <strong>in</strong>itialf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs highlighted critical areas of need to lowerthe <strong>in</strong>cidence of fistula <strong>and</strong> treat exist<strong>in</strong>g cases. 3In response, <strong>UNFPA</strong> <strong>and</strong> partners launched theCampaign to End <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2003.Photo credit: GMB Akash/Panos Pictures/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong><strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong>

Photo credit: Micol Zarb/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong>To date, 31 country-level needs assessments havebeen conducted <strong>in</strong> 29 countries 4 <strong>and</strong> many providenew <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to the social, cultural, <strong>and</strong> economicaspects of obstetric fistula. This publication aims toraise awareness about the underly<strong>in</strong>g dimensions ofmaternal mortality <strong>and</strong> morbidity by review<strong>in</strong>g thef<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of the 31 country-level assessments onobstetric fistula. Specifically, this publication:Highlights how perceptions, knowledge, <strong>and</strong>attitudes related to pregnancy <strong>and</strong> deliveryaffect maternal mortality <strong>and</strong> morbidity,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g obstetric fistula;Emphasises how social norms <strong>and</strong> culturalpractices impede or facilitate access to sexual<strong>and</strong> reproductive health care services; <strong>and</strong>Provides policy, programm<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> researchguidance to promote safe motherhood whileaddress<strong>in</strong>g obstetric fistula.Across country assessments, the typical fistula patientwas young, developed the fistula dur<strong>in</strong>g her firstpregnancy, <strong>and</strong> lived <strong>in</strong> a rural area. Additionally,obstetric fistula was observed among women whohad delivered four or more children. Many adolescentgirls <strong>and</strong> women liv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula did not utilisehealth services because of their limited decisionmak<strong>in</strong>gpower <strong>and</strong> attitudes <strong>and</strong> misperceptionsabout pregnancy <strong>and</strong> childbirth. Furthermore,political <strong>in</strong>security <strong>and</strong> economic <strong>in</strong>stability impededtransportation <strong>and</strong> access to maternal health careservices. F<strong>in</strong>ally, <strong>in</strong> most regions where women livedwith fistula, treatment services were m<strong>in</strong>imal tononexistent.This publication <strong>in</strong>cludes strategic recommendationsfor policy makers, programmers, <strong>and</strong> researchers onthe social, cultural, political, <strong>and</strong> economic dimensionsof maternal health, as seen through the lens ofobstetric fistula. Recommendations to improvematernal health care <strong>in</strong>clude:Promote legislation <strong>and</strong> policies to reducematernal mortality <strong>and</strong> morbidity, <strong>and</strong> toaddress underly<strong>in</strong>g sociocultural factors;Strengthen health system capacity to provideskilled maternity care that is accessible,affordable, <strong>and</strong> culturally acceptable;Strengthen health system capacity to manageobstetric fistula sensitively, ensur<strong>in</strong>g that care<strong>and</strong> treatment are subsidised <strong>and</strong> accessible;Raise awareness on sexual <strong>and</strong> reproductivehealth <strong>and</strong> reproductive rights to addressobstetric fistula;Promote the empowerment <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>tegrationof women <strong>in</strong>to communities post-surgery;Involve women who have lived with fistula asequal participants <strong>in</strong> maternal health programmeplann<strong>in</strong>g, implementation, <strong>and</strong> evaluation;Promote partnerships to share key lessons<strong>and</strong> to catalyse collective action; <strong>and</strong>Support research on obstetric fistula to improveunderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of the impact of maternalmorbidity <strong>and</strong> barriers to access<strong>in</strong>g vitalreproductive health services.Liv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony

Introduction[<strong>Obstetric</strong> fistula] is a terrible problem.The behaviour of a community variesfrom one area to another, from oneethnic group to another. In some cases,the victims are obliged to isolatethemselves, deserted by their husb<strong>and</strong>s.In other cases, they are accepted.Dr. El-Hadji Ousseynou Faye,Head of <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong>,SenegalGlobally, the burden of death <strong>and</strong> illness due topregnancy- <strong>and</strong> childbirth-related complications ismassive. Every m<strong>in</strong>ute one woman dies <strong>and</strong> another20 suffer from a devastat<strong>in</strong>g disability, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gobstetric fistula. <strong>Fistula</strong> is prevalent where maternalmortality is highest, especially where emergencyobstetric care, referral systems, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>frastructure arepoor. Exact prevalence rates are unknown, 5 yet it isgenerally accepted that a m<strong>in</strong>imum of 2 million girls<strong>and</strong> women live with untreated obstetric fistula, 6<strong>and</strong> at least 75,000 new cases occur each year. 7Moreover, estimates <strong>in</strong>dicate that up to 90% or moreof the babies do not survive the traumatic labour.The last decade has seen some progress <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>gmaternal mortality <strong>in</strong> Asia, Lat<strong>in</strong> America, <strong>and</strong>northern Africa. However, there was little or noimprovement <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa, where riskswere greatest for maternal death <strong>and</strong> illness <strong>and</strong>neonatal mortality. 8 A recent review of more than2,250 published studies on maternal mortalityrevealed a lack of research on obstructed labour,unsafe abortion, <strong>and</strong> haemorrhage <strong>in</strong> view of theirburden on maternal health. Furthermore, researchon the cultural <strong>and</strong> political determ<strong>in</strong>ants ofmaternal mortality was limited, 9 highlight<strong>in</strong>g theneed to better underst<strong>and</strong> critical underly<strong>in</strong>g riskfactors for maternal mortality <strong>and</strong> morbidity—<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gobstetric fistula—such as a girl’s or woman’s lowsocial status, limited access to health care,knowledge <strong>and</strong> perceptions about maternal health,sociopolitical context, cultural norms, <strong>and</strong> poverty. 10AFGHANISTANPAKISTANNEPALBANGLADESHINDIAMAURITANIAMALINIGERSENEGALCHADGAMBIABURKINASUDANFASOGUINEABENINTOGONIGERIASIERRA CÔTE GHANACENTRALLEONE D’IVOIREAFRICAN REPUBLICLIBERIACAMEROONEQUATORIALGUINEACONGODEMOCRATICREPUBLICOF CONGOERITREAETHIOPIAUGANDAKENYARWANDABURUNDIUNITEDREPUBLIC OFTANZANIADJIBOUTISOMALIAYEMENANGOLAZAMBIAMALAWIMOZAMBIQUEDEMOCRATICREPUBLIC OFTIMOR-LESTECaribbeanSOUTHAFRICACampaign to End <strong>Fistula</strong> CountriesHAITI<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong>

S<strong>in</strong>ce 2003, the global Campaign to End <strong>Fistula</strong> hasworked to reduce the <strong>in</strong>cidence of obstetric fistulathrough advocacy, research, <strong>and</strong> programme<strong>in</strong>terventions, <strong>and</strong> to improve <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease access totreatment services for women with obstetric fistula.The Campaign’s exploratory needs assessments shedlight on social, cultural, political, <strong>and</strong> economiccontexts <strong>in</strong> which fistula occurs <strong>and</strong> contribute to ourunderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of maternal mortality <strong>and</strong> morbidity.Data was gathered from key <strong>in</strong>formants, serviceproviders, girls <strong>and</strong> women liv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula, <strong>and</strong>community members through <strong>in</strong>terviews, surveys,focus groups, <strong>and</strong> document reviews.The assessments highlighted unique countryexperiences, common challenges, <strong>and</strong> successfulapproaches. However, more data needs to begathered regard<strong>in</strong>g women whose fistulas havebeen treated, models of re<strong>in</strong>tegration, health careprovider attitudes, <strong>and</strong> costs of fistula to families<strong>and</strong> the health care system. This data can help showthe role of provider attitudes <strong>in</strong> adolescent girls’<strong>and</strong> women’s access to vital maternal healthservices, determ<strong>in</strong>ants <strong>in</strong> the affordability of fistulatreatment, opportunities <strong>and</strong> challenges <strong>in</strong> life afterfistula treatment, <strong>and</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>ants of maternalhealth <strong>and</strong> economic well-be<strong>in</strong>g.This advocacy publication <strong>in</strong>cludes:An overview of the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from 31 countrylevelneeds assessments conducted <strong>in</strong> Africa,Asia, <strong>and</strong> the Arab states from 2001 to 2006on the cultural, social, economic, <strong>and</strong> politicaldeterm<strong>in</strong>ants of fistula;Detailed f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from six select countries:Bangladesh, Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso, Cameroon,Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea,<strong>and</strong> Sudan;Promis<strong>in</strong>g practices; <strong>and</strong>Strategic recommendations for policy makers,programmers, <strong>and</strong> researchers as they relate tothe social, economic, <strong>and</strong> political contexts <strong>in</strong>which obstetric fistula occurs.Photo credit: GMB Akash/Panos Pictures/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong>Liv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony

Photo Credit: GMB Akash/Panos Pictures/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong><strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong>

<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong>I endured 5 days with delivery pa<strong>in</strong>s.I was f<strong>in</strong>ally transferred to the hospital<strong>and</strong> the foetus was dead. After 3 weeks,I started to feel constant flows <strong>in</strong> myvag<strong>in</strong>a, <strong>and</strong> the odour was very bad. Thesituation has persisted for 10 years.Leak<strong>in</strong>g ur<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> faeces can lead to other medicalcomplications, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g genital sores/ulcerations,dehydration, frequent <strong>in</strong>fection, <strong>and</strong> kidney disease.Social isolation <strong>and</strong> stigma often lead to psychologicaltrauma, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g depression, anxiety, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> somecases suicide. S<strong>in</strong>ce the effects of the fistula may result<strong>in</strong> loss of f<strong>in</strong>ancial support or <strong>in</strong>ability to work, manywomen are pushed further <strong>in</strong>to poverty. Ensur<strong>in</strong>gfistula treatment services <strong>and</strong> psychosocial support forre<strong>in</strong>tegration post-surgery is therefore imperative.26-year-old woman,Equatorial Gu<strong>in</strong>eaProlonged labour <strong>and</strong> obstructed labour are majorcauses of maternal mortality <strong>and</strong> morbidity such asobstetric fistula. They occur <strong>in</strong> approximately 5%of births, caus<strong>in</strong>g 8% of maternal deaths. Often,labour is prolonged when the mother’s pelvis is toosmall or the baby is too large for a vag<strong>in</strong>al delivery.Adolescent girls may be especially at risk forobstructed labour, as their pelvises may not befully developed. 11When adolescent girls <strong>and</strong> women experienceprolonged labour for as short as 24 hours <strong>and</strong> areunable to travel to a health facility for a Caesareansection, the compression of tissues between thebaby’s head <strong>and</strong> the woman’s pelvis cuts off bloodflow to the bladder <strong>and</strong> rectum. The tissue dieswith<strong>in</strong> 3–10 days, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> an open<strong>in</strong>g, or fistula,between the vag<strong>in</strong>a <strong>and</strong> the bladder <strong>and</strong>/or rectum<strong>and</strong> chronic <strong>in</strong>cont<strong>in</strong>ence for the woman. Severenerve damage often affects a woman’s ability towalk. 12,13 In up to 90% of cases, the baby is stillbornor dies with<strong>in</strong> weeks.Other types of gynaecological fistula do exist <strong>and</strong>are usually the result of cervical cancer, radiationtherapy, or <strong>in</strong>juries result<strong>in</strong>g from surgery. <strong>Fistula</strong>may also result from sexual violence, more often<strong>in</strong> conflict <strong>and</strong> post-conflict sett<strong>in</strong>gs. 14 However,the vast majority of fistula globally are due toobstetric causes.The fact that obstetric fistula has been virtuallyelim<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong> the developed world is a clear rem<strong>in</strong>derthat the problem can be prevented through improvedaccess to high-quality maternal health services,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g family plann<strong>in</strong>g, skilled delivery care,emergency obstetric care, <strong>and</strong> postnatal care.Moreover, the fact that the majority of cases occuramong young women <strong>and</strong> adolescent girls meansthat we need to help them to delay pregnancy <strong>and</strong>have greater access to maternal health care.<strong>Fistula</strong> prevention, treatment, <strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>tegrationrequire consideration of the broader socioculturalfactors, such as low status of women, lack ofdecision-mak<strong>in</strong>g autonomy, marriage <strong>and</strong> pregnancyat a young age, lack of knowledge about labourcomplications, <strong>and</strong> a culture of home birth<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>Health</strong> system factors <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong>sufficientemergency obstetric care <strong>and</strong> skilled attendants,<strong>and</strong> delayed or unavailable Caesarean sections.Liv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony

Perspectives on <strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong>There is no joy anymore <strong>in</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g withothers, lonel<strong>in</strong>ess takes over. You loseyour habits for cook<strong>in</strong>g, visit<strong>in</strong>g others -<strong>and</strong> all this makes me sad.Woman,Burk<strong>in</strong>a FasoThis section presents the voices of adolescent girls<strong>and</strong> women liv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula, <strong>and</strong> their familymembers, communities, <strong>and</strong> health care providers.Information was gathered through <strong>in</strong>terviews,focus groups, hospital chart reviews, <strong>and</strong> surveys.Respondents shared their perspectives on maternalhealth, life with obstetric fistula, the causes offistula, the context <strong>in</strong> which it occurred, treatment,<strong>and</strong> re<strong>in</strong>tegration.Life with<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong>Nobody wants to stay with me due to thesmell of ur<strong>in</strong>e. Even my husb<strong>and</strong> sometimesblames me for my condition.22-year-old woman,BangladeshAcross the country assessments, the majority ofwomen <strong>in</strong>terviewed had married young, lived <strong>in</strong>remote <strong>and</strong> low-resource areas, <strong>and</strong> had limitedaccess to obstetric care services. Most developedobstetric fistula dur<strong>in</strong>g their first pregnancy, buta significant number, experienced fistula later <strong>in</strong>life after previous vag<strong>in</strong>al deliveries. Some women,especially those liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> remote areas, had nohealth care dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy <strong>and</strong> had laboured athome. Distance, poor roads, <strong>and</strong> cost were notedas barriers to maternal health care <strong>in</strong> many ofthe assessments.Home deliveries with elder female relatives ortraditional birth attendants were a commontradition across countries. Family pressure washighlighted, especially <strong>in</strong> Kenya, Bangladesh, <strong>and</strong>Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso, as limit<strong>in</strong>g utilisation of health services.In many countries, use of antenatal care wasassociated with bad luck <strong>and</strong> difficult deliverieswere l<strong>in</strong>ked with <strong>in</strong>fidelity <strong>and</strong> witchcraft.Reactions <strong>and</strong> levels of support from family members<strong>and</strong> husb<strong>and</strong>s varied across the assessments. Women<strong>and</strong> adolescents liv<strong>in</strong>g with obstetric fistulafrequently described rejection by husb<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong>family members. Women reported be<strong>in</strong>g physicallyisolated from their families <strong>in</strong> West Darfur <strong>and</strong>mistreated by <strong>in</strong>-laws <strong>in</strong> Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso. In contrast,husb<strong>and</strong>s cont<strong>in</strong>ued to support their wives <strong>in</strong>some cases. For example, more than half of the71 women liv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula <strong>in</strong>terviewed <strong>in</strong> theCentral African Republic <strong>in</strong>dicated that theirhusb<strong>and</strong>s provided moral <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial support.I am distasteful <strong>in</strong> theeyes of others. It is God’s will.48-year-old woman,MaliAcross country assessments, many women liv<strong>in</strong>gwith fistula viewed their condition as the will ofGod or even a punishment from God. Women toldof liv<strong>in</strong>g on the marg<strong>in</strong>s of society due to theirown self-imposed isolation because of the smell,embarrassment, <strong>and</strong> fear of ostracism from thecommunity. Women also spoke of their <strong>in</strong>ability topractice any type of economic activity <strong>and</strong> hencetheir f<strong>in</strong>ancial dependence on others. Some women<strong>in</strong> Mali were excluded from religious activities asthey were perceived as unclean. <strong>Fistula</strong> patients <strong>in</strong>Bangladesh described be<strong>in</strong>g given less priority foradmission due to limited beds <strong>and</strong> reproach relatedto the smell of ur<strong>in</strong>e.<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong>

Everyone has rejected me.Cure me or kill me!Woman,BangladeshAccess to treatment was closely tied to affordabilityof surgery, f<strong>in</strong>ancial means, geographic access, <strong>and</strong>knowledge on treatment. Obstacles to treatment<strong>in</strong>cluded the cost of surgery (rang<strong>in</strong>g from US$20to US$400) plus transport <strong>and</strong> lodg<strong>in</strong>g. Treatmentwas not affordable for numerous women <strong>in</strong> allcountries. Many accepted their condition as a curse.Conversely, some women received f<strong>in</strong>ancial assistancefrom their biological family <strong>and</strong> friends. In Tanzania,women reported travell<strong>in</strong>g 500 kilometres or more toreach a major fistula centre. Distances were probablytoo great f<strong>in</strong>ancially <strong>and</strong> socially for many others.Three Delays Dur<strong>in</strong>g aProlonged Labour thatImpede Women’s Accessto Quality Care:• Decision to seek care from a skilledattendant: Cultural preference forhome delivery, limited knowledgeof maternal health, <strong>and</strong> limitedtransport delayed decisions to seekcare. Frequently, family membersdeterm<strong>in</strong>ed when <strong>and</strong> where to seekcare, often <strong>in</strong> conflict with the needs<strong>and</strong> wishes of the woman.• Reach<strong>in</strong>g a health care facility:Even when a decision to seek carehad been made, poor roads, the highcost of transportation, <strong>and</strong> longdistances delayed women’s access tohealth facilities <strong>and</strong> emergency care.• Receiv<strong>in</strong>g emergency obstetric careat the facility: Once some womenreached a health facility, skilledpersonnel <strong>and</strong>/or supplies werelack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> emergency obstetriccare was delayed.The assessments highlighted the need for moreadvocacy <strong>and</strong> education regard<strong>in</strong>g treatment <strong>and</strong>re<strong>in</strong>tegration programmes. A 26-year-old Sudanesewoman was study<strong>in</strong>g midwifery “<strong>in</strong> order to assistwomen <strong>in</strong> rural areas not to go through [her]personal experience”. She gives testimony to how awoman who has lived with fistula can beempowered to be a catalyst for social change.Thanks to a scholarship from the Gene<strong>in</strong>a MidwiferySchool <strong>in</strong> the Sudan, she is embark<strong>in</strong>g on a careerto promote maternal health <strong>and</strong> to fight aga<strong>in</strong>stobstetric fistula.Life after <strong>Fistula</strong> TreatmentWhen I returned to the village, thosewho did not believe that I was healedwere embarrassed when I saw them.I have become a person aga<strong>in</strong>.48-year-old woman,MaliLimited <strong>in</strong>formation is available on women’s lives afterfistula treatment. Women <strong>in</strong> Mozambique spoke ofgreat pressure to become pregnant aga<strong>in</strong> after surgicaltreatment. More than half of the 568 women seek<strong>in</strong>gtreatment at two national hospitals <strong>in</strong> Mali from 2000to 2002 were no longer sexually active. In Eritrea,women who had undergone surgical treatmentdescribed sex as improved but still pa<strong>in</strong>ful. Those whohad refra<strong>in</strong>ed from sexual <strong>in</strong>tercourse lacked thedesire or <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> sex. Six women <strong>in</strong> Eritrea stillexperienced leakage after surgery <strong>and</strong> felt isolated.I did not know that one dayI would be like other women,because the problem was big.48-year-old woman,TanzaniaRe<strong>in</strong>tegration care was not commonly availableat health facilities provid<strong>in</strong>g fistula treatment.Assessments recommended skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> thecreation of job opportunities for fistula patients aftera successful treatment to facilitate re<strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>in</strong>tosociety <strong>and</strong> a productive <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent life.Liv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony

Photo credit: Sven Torf<strong>in</strong>n/Panos Pictures/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong>In some sett<strong>in</strong>gs, women had experienced suchsevere stigma that they were reluctant to returnhome <strong>and</strong> were liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> or near the hospital wherethey received treatment. But successful treatmentdrastically changed the lives of many women aswell. In a study conducted by the Women’s DignityProject <strong>in</strong> Tanzania, nearly all women who hadundergone successful fistula treatment <strong>in</strong>dicated thatthey no longer felt isolated from the community.Many described feel<strong>in</strong>g like a “normal humanbe<strong>in</strong>g”, <strong>and</strong> were able to return to their ord<strong>in</strong>ary lives.The majority <strong>in</strong>dicated that they were able to engage<strong>in</strong> economic activities <strong>and</strong> perform daily chores withlittle difficulty. Self-esteem improved markedly formany women after treatment because they couldnow attend community <strong>and</strong> family gather<strong>in</strong>gs.I want to start a new life.I want to have friends.I want to share my story.32-year-old woman,EritreaIn many studies, treated fistula patients <strong>and</strong>their families were highlighted as potentialcommunity-level educators for the prevention<strong>and</strong> treatment of obstetric fistula <strong>and</strong> promotersof maternal health <strong>and</strong> safe delivery. For example,after receiv<strong>in</strong>g treatment, four Eritrean womenreported advis<strong>in</strong>g community members on safemotherhood practices <strong>and</strong> prevention of obstetriccomplications. A 19-year-old Eritrean woman washappy with the outcome of her fistula operation<strong>and</strong> noted that she would recommend the surgeryto other women <strong>in</strong> her village, advis<strong>in</strong>g them notto delay treatment.Family Members of WomenLiv<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong>If people are aware, they can preventfistula <strong>and</strong> solve this problem. Be<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>formed, they have better self-esteem.Father of an 18-year-old womanliv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula,EritreaAcross most countries reviewed, family membersplayed a critical role <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g access toessential obstetric care—<strong>in</strong> some cases elder women,<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> other cases husb<strong>and</strong>s. In many situations,family members described delivery as a privateaffair for only close female relatives. Cultural norms<strong>and</strong> a lack of confidence <strong>in</strong> the health sector keptmany women from receiv<strong>in</strong>g care before, dur<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>and</strong> after birth. Strong preference for home deliveryfor first births was cited across many of the countries.Decisions about when <strong>and</strong> where to seek care weremade by male elders <strong>in</strong> Malawi, by female elders <strong>in</strong>Eritrea, <strong>and</strong> by mothers-<strong>in</strong>-law, husb<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> otherfamily members <strong>in</strong> Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso, Bangladesh, <strong>and</strong>Ghana. Such family decisions were often <strong>in</strong> conflictwith the pregnant woman’s wishes <strong>and</strong> health needs.A woman’s primary doctor is first <strong>and</strong>foremost her husb<strong>and</strong>. It is necessarythat the husb<strong>and</strong> support his wife beforeor after awareness of the condition.Man,Côte d’Ivoire<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong>

Family consultations often created long delays <strong>in</strong>seek<strong>in</strong>g assistance from a health facility whenbirth<strong>in</strong>g complications arose. In many countries,a woman’s unfaithfulness to her husb<strong>and</strong> wasconsidered the cause of a difficult labour, thus<strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g decisions to transport her to emergencyobstetric care. Nigerian men <strong>in</strong>terviewed did notwant women to have antenatal care for fear ofHIV test<strong>in</strong>g. In Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso, men stated that theywere not <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> pregnancy <strong>and</strong> childbirth<strong>and</strong> admitted to hav<strong>in</strong>g no knowledge of maternalhealth, but were responsible for mak<strong>in</strong>g decisionswhen there was a complication.Most husb<strong>and</strong>s <strong>in</strong>terviewed <strong>in</strong> Bangladesh <strong>in</strong>dicatedthat their wives no longer had <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> sexual<strong>in</strong>tercourse after the fistula occurred. In Bangladesh,Mozambique, <strong>and</strong> the Central African Republic, somehusb<strong>and</strong>s had remarried after the fistula occurred<strong>and</strong> the wives affected by fistula rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> thehousehold as servants. Some women said that theyhad failed <strong>in</strong> their duties as sexual partners.I am embarrassed when my friendscome by. If she passes next to them,I can tell that they are upset by theodour. I am really tired by all of this.54-year-old man, MaliA 52-year-old husb<strong>and</strong> described his hopes for hiswife’s fistula treatment by say<strong>in</strong>g, “I will be born fora second time. She will be born for a second time.She will socialise. She will go to town. She will visither brother.”Photo credit: Lucian Read/WpN/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong>10Liv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony

Voices from the CommunityUsually the woman provokes this.When she leaves her husb<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> hassexual relations with another man, ithappens that her husb<strong>and</strong> will cast aspell on her <strong>and</strong> she will have a fistula.Elderly woman,Burk<strong>in</strong>a FasoThe causes <strong>and</strong> treatment of obstetric fistulawere not well known with<strong>in</strong> most communities,especially given its hidden nature, <strong>and</strong> thecondition was shrouded <strong>in</strong> a complex web ofmisperceptions. Across country assessments, manycommunity members l<strong>in</strong>ked difficult labour <strong>and</strong>fistula to a spell cast by someone offended bythe woman or as a punishment for the woman’s<strong>in</strong>fidelity. In Côte d’Ivoire, community membersbelieved that obstetric fistula was due tosupernatural causes or promiscuity. Interviewees<strong>in</strong> Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso l<strong>in</strong>ked obstetric fistula to adultery<strong>and</strong> to the “evil eye”.<strong>Fistula</strong> occurs when the woman eatsfood that is not good for her when sheis pregnant. Dur<strong>in</strong>g delivery, the childis so big that it tears the mother.Woman,CameroonFocus group participants <strong>in</strong> Côte d’Ivoire displayedattitudes of rejection <strong>and</strong> discrim<strong>in</strong>ation towardswomen liv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula. Community assessments<strong>in</strong> Kenya <strong>and</strong> Tanzania <strong>in</strong>dicated that women whogave birth by Caesarean section or had obstetricfistula were not womanly. Sometimes the veryidioms used to describe this condition revealprejudices <strong>and</strong> misunderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g. For example,<strong>in</strong> Mali obstetric fistula was described as “a womanwho becomes silent when the ur<strong>in</strong>e starts to flow”<strong>and</strong> “a wish come true from a co-wife <strong>in</strong> apolygamous marriage”. In Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso, womenliv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula were described as “the womanru<strong>in</strong>ed by birth” <strong>and</strong> punished by the fistula.In contrast, <strong>in</strong> select communities <strong>in</strong> Kenya<strong>and</strong> Cameroon, assessments showed higher levelsof community support <strong>and</strong> sympathy for thiscondition. In other countries, a number ofcommunity-based organisations were develop<strong>in</strong>gre<strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>and</strong> counsell<strong>in</strong>g programmes withlimited resources. In West Darfur, these <strong>in</strong>cludedsocial <strong>and</strong> psychological support as part of thetreatment process.<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong> 11

Traditional Birth AttendantsThis is not a good illness.It is a shameful illness… it ismore than AIDS. It is death.Traditional birth attendant,Côte d’IvoireLike other community members, some traditionalbirth attendants <strong>in</strong>dicated that difficult labour iscaused by conjugal <strong>in</strong>fidelity or do<strong>in</strong>g someth<strong>in</strong>gthat is prohibited. They believed that if a womanadmits the “truth”, her labour will be eased. Healers<strong>in</strong> Ben<strong>in</strong> described help<strong>in</strong>g women liv<strong>in</strong>g withfistula to overcome their “curse”. In Mali, traditionalFemale Genital Mutilation/Cutt<strong>in</strong>g (FGM/FGC)Various forms of FGM/FGC arepracticed <strong>in</strong> many of the countrieshighlighted <strong>in</strong> this report, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gEritrea, Mali, Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan,<strong>and</strong> others. FGM/FGC consists ofcutt<strong>in</strong>g away part or all of the femaleclitoris, labia majora, <strong>and</strong> labia m<strong>in</strong>ora.With <strong>in</strong>fibulation, the clitoris <strong>and</strong> partof the labia majora <strong>and</strong> m<strong>in</strong>ora areexcised. The rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g parts of thevulva are sewn or p<strong>in</strong>ned together,leav<strong>in</strong>g only a small open<strong>in</strong>g for thepassage of ur<strong>in</strong>e, menstrual flow, <strong>and</strong>sexual <strong>in</strong>tercourse.Some types of FGM/FGC, particularly<strong>in</strong>fibulation, may be correlated withprolonged, obstructed labour, which<strong>in</strong> cases where timely obstetric careis not provided could result <strong>in</strong> obstetricfistula. A 2006 WHO study found<strong>in</strong>creased risk of obstetric complicationswith certa<strong>in</strong> types of FGM/FGC. 15birth attendants believed that fistula occurs when apregnant woman consumes sweet foods or certa<strong>in</strong>gra<strong>in</strong>s such as rice or small millet. In other countries,traditional healers cited cervical cancer or a tearcaused by the baby’s hair as possible causes ofobstetric fistula.Community members <strong>in</strong> Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso <strong>in</strong>dicated thattraditional birth attendants often prolonged labour<strong>and</strong> delayed access to a health facility by try<strong>in</strong>g toextract the baby or shift its position. Communitymembers <strong>in</strong> Niger described how traditional birthattendants dangerously pressed their elbows orknees on a woman’s belly, try<strong>in</strong>g to speed updelivery. Additionally, community membersdescribed how traditional birth attendants helda pregnant woman upside down precariously<strong>and</strong> shook her <strong>in</strong> the hope of reposition<strong>in</strong>g abreech presentation.The results of [pregnancy] management byTBAs are disastrous due to the delays.They [wait] too long, do not know where tostart, <strong>and</strong> do not even know where to stop.<strong>Health</strong> care provider,KenyaTraditional birth attendants <strong>in</strong> Bangladesh <strong>and</strong>Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso revealed limited knowledge of fistula<strong>and</strong> admitted that they were not capable of treat<strong>in</strong>gfistula. In several country studies, women <strong>and</strong> theirfamilies were stripped of their assets by traditionalhealers who had promised to cure the fistula butwere not able to do so.When asked what steps are needed to solve thefistula problem, one traditional birth attendant <strong>in</strong>Côte d’Ivoire stated, “You have to create awareness,you have to tell everybody.”12Liv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony

<strong>Health</strong> Care ProvidersThe existence of fistula is the barometerof maternal health <strong>in</strong> the country. If yearby year fistula decreases, we know thatmaternal health is improv<strong>in</strong>g.Dr. Kalilou Ouattara,fistula surgeon, Mali<strong>Health</strong> care providers <strong>in</strong> general noted a lack ofawareness among community members on thecauses <strong>and</strong> consequences of obstetric fistula. Inparticular, providers noted contribut<strong>in</strong>g factors suchas the low status of women, limited knowledgeof the consequences of prolonged labour, earlychildbear<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> few female health care providers.Accord<strong>in</strong>g to health professionals <strong>in</strong>terviewed <strong>in</strong>Côte D’Ivoire <strong>and</strong> Sudan, fistula occurs almostexclusively <strong>in</strong> women deliver<strong>in</strong>g at home with atraditional birth attendant.The reluctance to seek out a health care providerdur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy <strong>and</strong> labour was frequently due tothe lack of obstetric services <strong>in</strong> the regions wherewomen lived. Appropriate medical attention wasoften lack<strong>in</strong>g at facilities, <strong>and</strong> women did not getthe quality care they needed, especially <strong>in</strong> cases ofemergency. For example, health care providersacross countries <strong>and</strong> regions noted an <strong>in</strong>sufficientnumber of qualified personnel attend<strong>in</strong>g deliveries.OB/GYNs have shown little <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g how to perform fistularepairs. Even providers who havethe skills to do simple repairs refuse.One probable reason is stigma.<strong>Health</strong> care provider,MozambiqueFew specialist surgeons or obstetric gynaecologistswere identified to be tra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> fistula surgery <strong>in</strong>most countries. Many delivery personnel <strong>in</strong>terviewedhad no knowledge of obstetric fistula. Limitedopportunities <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>centives existed for tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>fistula detection <strong>and</strong> treatment. Few local physiciansor visit<strong>in</strong>g expatriate doctors performed fistulasurgeries, <strong>and</strong> most treatment facilities lackedbasic equipment.Photo credit: Lucian/WpN/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong>Information about fistula <strong>and</strong> timely referrals werefound to be lack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> health facilities <strong>in</strong> manycountries. Women <strong>in</strong> Eritrea noticed the fistulaproblem while still <strong>in</strong> the hospital, but received no<strong>in</strong>formation about treatment. In Zambia, womenliv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula were referred to hospitals that didnot offer treatment. <strong>Health</strong> providers <strong>in</strong> Bangladeshsaid that patients lacked <strong>in</strong>formation on theavailability of fistula treatment services. Even freeservices were not sufficient for the poorest patients<strong>in</strong> Bangladesh, as they could not afford medic<strong>in</strong>e,transportation, food, <strong>and</strong> accommodations.Some women travelled great distances <strong>and</strong> evenacross national borders to receive treatment.District adm<strong>in</strong>istrators <strong>in</strong> Ben<strong>in</strong> noted that womenseek treatment <strong>in</strong> Niger, Nigeria, or Togo toma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> their anonymity. In Ben<strong>in</strong>, fistula carewas described as a luxury surgery for a social crisis.Hospital providers <strong>in</strong> Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso <strong>in</strong>dicated thatwomen delayed seek<strong>in</strong>g treatment with a healthprofessional or even go<strong>in</strong>g to a health facility dueto a lack of f<strong>in</strong>ancial resources. Few telephones<strong>and</strong> limited ambulance service made referrals fortreatment difficult <strong>in</strong> many countries.<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong> 13

The Context <strong>in</strong> Which <strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> OccursBecause of the cultural requirement todeliver the first baby at home, Chepchumba…aged 14 laboured at home with thetraditional birth attendant [for] 2 days.…They walked … another 2 days to thehospital … <strong>and</strong> delivered a stillbirth <strong>and</strong> …developed sepsis <strong>and</strong> [fistula].<strong>Health</strong> care provider,KenyaThis overview exam<strong>in</strong>es the context <strong>in</strong> which fistulaoccurs, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g social <strong>and</strong> cultural norms, thepolitical sett<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> the economic situation thatoften def<strong>in</strong>e women’s lives. A girl’s or woman’sbackground <strong>and</strong> her role <strong>in</strong> her environment<strong>in</strong>fluence her sexual <strong>and</strong> reproductive healthoutcomes, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g her risk for obstetric fistula.Photo credit: Lucian Read/WpN/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong>Social <strong>and</strong> Cultural ContextCultural beliefs <strong>and</strong> social values preventedadolescent girls <strong>and</strong> women from mak<strong>in</strong>g decisionsabout their own bodies as well as their health <strong>in</strong> allcountries. Generally, women liv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula hadlow literacy skills, low status <strong>in</strong> the family, <strong>and</strong> fewyears of school<strong>in</strong>g. Knowledge regard<strong>in</strong>g familyplann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> safe motherhood was often limited<strong>and</strong> access to contraceptives restricted.I married when I was 14 years old.My family did not discuss with me the agewhen I marry <strong>and</strong> who I marry because awoman has no op<strong>in</strong>ion <strong>in</strong> such matters.26-year-old woman,SudanAcross assessments, large proportions of womendelivered at home with extremely low rates ofCaesarean births <strong>in</strong> rural areas. Among the womenwho gave birth at home, many were assisted byfemale family members or traditional birth attendantswith no formal tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. When complications arosedur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy, access to necessary obstetric carewas often avoided or delayed due to family pressuresfor home deliveries <strong>and</strong> misperceptions of thecauses of complications.In many assessments, child marriage <strong>and</strong> earlychildbear<strong>in</strong>g were the norm <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creasedvulnerability by contribut<strong>in</strong>g to gender <strong>in</strong>equities<strong>in</strong> education, work, <strong>and</strong> decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g. Girls weremarried at their first menstrual flow (10 to 15 yearsold) <strong>in</strong> numerous countries, <strong>and</strong> as young as age 9<strong>in</strong> Nigeria. These adolescent girls often had lessaccess to reproductive health <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>and</strong>services, as well as contraceptives. Conversely, wherecases of fistula were noted among older womenwith children, pregnancies were not well spaced<strong>and</strong> high fertility rates were prevalent.14Liv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony

Political <strong>and</strong> EconomicSituationThe doctors [told] my husb<strong>and</strong> totake me to Ouagadougou. Therewas no money. That is why thisth<strong>in</strong>g dragged on for 21 years.50-year-old woman,Burk<strong>in</strong>a FasoPoverty <strong>and</strong> gender <strong>in</strong>equality were evidentthroughout the assessments. The data illum<strong>in</strong>atedgrave disparities <strong>in</strong> the quality of life betweenpoorer <strong>and</strong> wealthier women. Poverty <strong>and</strong>women’s status had a negative impact on accessto family plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> skilled care, as well asmaternal health outcomes. Research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsshowed that most women who developed fistulatended to live <strong>in</strong> rural, low-resource areas withlimited access to health facilities that might offerhigh-quality antenatal <strong>and</strong> delivery care. Longdistances to health facilities <strong>and</strong> a lack ofresources added to delays <strong>in</strong> gett<strong>in</strong>g quality care<strong>in</strong> the case of complications dur<strong>in</strong>g labour.The security situation affected themovements of vehicles to <strong>and</strong> fromlocalities <strong>and</strong> thus affected thetraditional referral help forclients of obstructed labour.Dr. Salih, fistula surgeon,West Darfur, SudanSeveral countries were <strong>in</strong> conflict or post-conflictsituations or had been affected by civil war <strong>in</strong>neighbour<strong>in</strong>g countries, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Central AfricanRepublic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, Somalia,Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, <strong>and</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>a.A country’s political <strong>in</strong>stability contributed to theprecarious health of its population. Political unrestreduced f<strong>in</strong>ancial resources for health services,destroyed the health <strong>in</strong>frastructure, <strong>and</strong> contributedPhoto Credit: GMB Akash/Panos/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong>to high maternal <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant mortality <strong>and</strong>morbidity. Insecurity <strong>in</strong> conflict zones madetransportation to health facilities difficult.Destruction of roads impeded the distribution offood, medic<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>and</strong> supplies. In some cases heavyfight<strong>in</strong>g had destroyed cl<strong>in</strong>ics <strong>and</strong> electrical <strong>and</strong>water systems.<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong> 15

16Photo Credit: GMB Akash/Panos Pictures//On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong>Liv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony

Select Country Assessments: Key F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsIf my three girls were boys … theywould carry me to Ouagadougouso that I could get treated.40-year-old woman,Burk<strong>in</strong>a FasoCountry-level needs assessments provide importantlessons learned <strong>and</strong> strategic recommendations forfuture policy, programm<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> research. This sectionhighlights the methodologies utilised <strong>and</strong> the majorf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from six select countries: Bangladesh,Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso, Cameroon, Democratic Republic ofCongo, Eritrea, <strong>and</strong> Sudan.BangladeshIt is difficult to cont<strong>in</strong>ue work <strong>and</strong>do other th<strong>in</strong>gs. White discharge,blisters, <strong>and</strong> itch<strong>in</strong>g are all disturb<strong>in</strong>g.22-year-old woman,BangladeshIn Bangladesh, more than 40% of people live <strong>in</strong>poverty <strong>and</strong> the status of women is low. Theaverage age of marriage is 15 years old, <strong>and</strong>motherhood <strong>and</strong> early childbirth are consideredextremely important cultural obligations. Mostpregnant women do not receive antenatal care(63%) <strong>and</strong> most births occur at home (92%),primarily with the assistance of untra<strong>in</strong>edtraditional birth attendants, relatives,or friends. In this context, the underly<strong>in</strong>g factorsmake the likelihood of fistula high. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to anational study, it is estimated that more than416,000 women live with fistula. 16From July to September 2003, Engender<strong>Health</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>UNFPA</strong> conducted an analysis of obstetric fistula<strong>in</strong> Bangladesh, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a literature review <strong>and</strong>qualitative research. In-depth <strong>in</strong>terviews wereconducted with fistula patients (132), relatives/caregivers (72), service providers (30), <strong>and</strong> policymakers to assess the overall situation of fistula <strong>in</strong>Bangladesh. The study exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>dividual, familial,<strong>and</strong> socioeconomic risk factors of obstetric fistula,<strong>and</strong> challenges <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g care <strong>and</strong> rehabilitation.Researchers highlighted the grave need for rais<strong>in</strong>gawareness at the community level on potentiallabour complications <strong>and</strong> emergencies.Furthermore, the study revealed that significantnumbers of women are unaware of fistula treatmentpossibilities.More than half of the fistula patients <strong>in</strong>terviewed <strong>in</strong>Bangladesh had developed obstetric fistula as anoutcome of their first pregnancy (54%). The majorityexperienced prolonged labour (72%) dur<strong>in</strong>g a homedelivery (68%). All had knowledge of antenatal care,but more than half were not comfortable us<strong>in</strong>g thehealth facility due to family objections, lack of privacy,<strong>and</strong> discomfort with male practitioners. Most of thefistula patients <strong>in</strong>terviewed were illiterate (68%),likely contribut<strong>in</strong>g to misconceptions <strong>and</strong>superstitions about pregnancy <strong>and</strong> birth.Prevention <strong>and</strong> managementof fistula casesService providers remarked that it is critical that“the [health] care system be more responsive to theprevention <strong>and</strong> management of fistula cases.” Theutilisation of antenatal care was very low acrossBangladesh. Most fistula patients had limitedunderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of potential labour complications<strong>and</strong> obstetric emergencies. Researchers <strong>in</strong>dicatedthat safe delivery would require that doctors atlocal <strong>and</strong> district levels have appropriate knowledge<strong>and</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the management of deliverycomplications, the early management of obstetricfistula, <strong>and</strong> the capacity to refer fistula cases todistrict or university hospitals that providetreatment. F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs emphasised the need to addressstigma <strong>and</strong> discrim<strong>in</strong>ation because health facilitiesgave low priority for admission to fistula patients.<strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong> 17

Barriers to <strong>and</strong> facilitatorsof treatmentTwelve out of 27 women had lived with fistula formore than 10 years, largely due to challenges <strong>in</strong>overcom<strong>in</strong>g barriers to access <strong>and</strong> treatment.Interviewees described embarrassment <strong>in</strong> discuss<strong>in</strong>gthe topic, lack of funds, no caregiver, distance fromthe health facility, <strong>and</strong> lack of knowledge on fistula<strong>and</strong> treatment. Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, hav<strong>in</strong>g lived withfistula for years, several women f<strong>in</strong>ally had soughttreatment because the constant ur<strong>in</strong>ation hadworsened <strong>and</strong> they were uncomfortable attend<strong>in</strong>greligious gather<strong>in</strong>gs.Underly<strong>in</strong>g factorsThe role of gender affects decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g power<strong>and</strong> health choices for women. Men who areeducated regard<strong>in</strong>g reproductive health issuesare more likely to be supportive dur<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy<strong>and</strong> make better health decisions. Researchersrecommended sensitis<strong>in</strong>g men on reproductivehealth <strong>and</strong> the importance of supportive,responsible behaviour among men—even fromadolescence when adult behaviour patterns areformed. Researchers noted that women were notrecognised as equal partners <strong>in</strong> relationships <strong>and</strong>marriage <strong>in</strong> Bangladeshi society. Husb<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong>female elders were primary decision makersregard<strong>in</strong>g access to health facilities <strong>and</strong> emergencyobstetric care, often restrict<strong>in</strong>g women’s access.<strong>Health</strong> providers described how the prevail<strong>in</strong>g cultureattributed difficult labour to a woman’s unfaithfulness.Women liv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula experienced disregard <strong>and</strong>mistreatment from husb<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>-laws dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>after a problematic delivery. One doctor noted that <strong>in</strong> a30-year practice only one husb<strong>and</strong> had accompaniedhis wife for the treatment of fistula. In contrast tothe health providers, the women themselves did notmention social isolation or mistreatment by theirhusb<strong>and</strong>s, despite more than half be<strong>in</strong>g separated,divorced, or widowed. Women <strong>in</strong>terviewees <strong>in</strong>dicatedthat they were no longer of use to their husb<strong>and</strong>sas a sexual partner. In fact, many accepted a shiftwith<strong>in</strong> the household from wife to maid as theirhusb<strong>and</strong>s took on another spouse.Burk<strong>in</strong>a FasoEverybody says it is because I committedadultery that I have fistula. Some makefun of me. In this type of situation, canI cont<strong>in</strong>ue to go anywhere?46-year-old woman,Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso<strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>and</strong> child mortality rates <strong>in</strong> Burk<strong>in</strong>a Fasoare among the highest globally. Estimates of maternaldeaths range from 484 to 1,400 deaths per 100,000live births accord<strong>in</strong>g to the Demographic <strong>and</strong><strong>Health</strong> Surveys from 1998/1999. The same datashows that 39% of pregnant women receive noantenatal care, <strong>and</strong> births are attended primarilyby traditional birth attendants (42%), healthpersonnel (31%), <strong>and</strong> family members (19.8%).Two qualitative research assessments wereconducted <strong>in</strong> three health regions <strong>in</strong> Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso<strong>in</strong> 2004. Twenty health agents, 24 key stakeholders/community leaders, <strong>and</strong> 4 fistula survivors <strong>in</strong>each of three districts (12 women total) were<strong>in</strong>terviewed. Twelve focus group discussions wereheld <strong>in</strong> each district with men, young women, <strong>and</strong>older women. In addition, a retrospective reviewof hospital registers was carried out <strong>in</strong> 2004 <strong>in</strong> allhospital facilities <strong>in</strong> Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso (n = 347). Theaverage age of fistula patients was 28 <strong>and</strong> almosthalf (49%) of patients sought treatment with<strong>in</strong> ayear. Among those with children, the mediannumber of live births before the fistula occurredwas two. Patients were <strong>in</strong> monogamous (47%)<strong>and</strong> polygamous (37%) marriages.Perceptions of the causesof fistulaGenerally, the respondents attributed fistulaoccurrence to punishment for bad behaviour. Inaddition, antenatal care is believed to br<strong>in</strong>g oncomplications dur<strong>in</strong>g delivery. However, those whol<strong>in</strong>ked fistula with pregnancy often mentioned culturalfactors, such as early marriage, early sexual activity<strong>and</strong> early pregnancy, female genital mutilation/cutt<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> traditional birth attendants’ practices.18Liv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony

Intergenerational differences <strong>in</strong> knowledgeregard<strong>in</strong>g causes of prolonged labour <strong>and</strong> risks offistula were evident. Young women had greaterawareness of fistula than older women. Youngerwomen made a l<strong>in</strong>k between childbirth <strong>and</strong> theonset of the fistula. Some said that fistula was dueto a tear dur<strong>in</strong>g childbirth, the duration of labour,<strong>and</strong> the size of the baby. Older women <strong>in</strong>terviewedsaid that a woman with fistula provoked her situation.Only one-third of the n<strong>in</strong>ety men <strong>in</strong>terviewed atthe community level knew about fistula.professionals was the only way to resolve theproblem. Even with this confession, none of thetraditional healers would admit to the women thatthey were <strong>in</strong>capable of deal<strong>in</strong>g with their condition.Traditional versus moderntreatmentMost women liv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula, follow<strong>in</strong>gcommunity customs, first sought treatment with atraditional healer. This was due <strong>in</strong> part to limitedf<strong>in</strong>ancial resources <strong>and</strong> women’s dependence ontheir husb<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> mothers-<strong>in</strong>-law. Thesetreatments, albeit quite costly, never produced thedesired results. Many women declared that theyreceived traditional treatments <strong>in</strong> va<strong>in</strong> for manyyears. After these unsuccessful attempts, somesought modern treatment.Researchers noted that younger women <strong>and</strong> somemen had greater confidence <strong>in</strong> professional healthcare providers. Seek<strong>in</strong>g professional treatment wasl<strong>in</strong>ked to f<strong>in</strong>ancial autonomy, accessibility oftreatment, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation about treatmentpossibilities. Only a t<strong>in</strong>y proportion of women liv<strong>in</strong>gwith fistula had access to <strong>in</strong>formation concern<strong>in</strong>gtreatment. Overall, women who had undergonesurgery for fistula constituted a very small m<strong>in</strong>ority<strong>in</strong> Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso. The community had littleknowledge <strong>and</strong> lacked the means to take care offistula cases. Sadly, many women were ab<strong>and</strong>oned<strong>and</strong> left to their own means.Over half of the 24 traditional healers <strong>in</strong>terviewedmistook fistula for ur<strong>in</strong>ary <strong>in</strong>cont<strong>in</strong>ence. Thehealers admitted that they were not capable oftreat<strong>in</strong>g fistula with their potions, nor with theirphysical treatments. They considered the illness tobe l<strong>in</strong>ked to a trauma, a tear, which could only behealed by suture. Almost all healers affirmed thatsurgery performed <strong>in</strong> a health facility by healthPhoto credit: Lucian Read/WpN/On behalf of <strong>UNFPA</strong><strong>Obstetric</strong> <strong>Fistula</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Inequities</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Maternal</strong> <strong>Health</strong> 19

CameroonThe traditional birth attendants say to becalm <strong>and</strong> wait it out … <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the meantime,a complication can develop. But at thehospital … well, they know better.Woman,CameroonCameroon’s population is 16.3 million <strong>and</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g.Seven percent of women of reproductive age usemodern contraceptives, <strong>and</strong> women have an averageof five children. Slightly more than half (54%)of deliveries occur <strong>in</strong> a health facility. Amongthose women who give birth at home, most areassisted by a traditional birth attendant. Theestimated maternal mortality ratio ranges from430 to 1,100 deaths per 100,000 live births.In 2004, a descriptive exploratory survey wasconducted on obstetric fistula <strong>in</strong> 50 health facilities<strong>in</strong> two prov<strong>in</strong>ces of northern Cameroon. Womenliv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula (63) <strong>and</strong> traditional birthattendants (101) were <strong>in</strong>terviewed, <strong>and</strong> focusgroups (22) were conducted with men <strong>and</strong> womenof reproductive age. Most women who developedfistula had been <strong>in</strong> labour, at home, for more than24 hours with only a traditional birth attendant.Reluctance to seek health careAmong women who were liv<strong>in</strong>g with or had livedwith fistula, use of antenatal care was limited.Reluctance to seek out health care services was dueto lack of money, distance from the health facility,<strong>and</strong> refusal of the husb<strong>and</strong>. In general, womenliv<strong>in</strong>g with fistula <strong>and</strong> community members notedthat emergency obstetric services were not available<strong>in</strong> their region. Community members felt that healthfacilities offered limited emergency services <strong>and</strong> didnot have proper equipment or adequate care formothers <strong>and</strong> newborns. Women relied on traditionalbirth attendants dur<strong>in</strong>g delivery <strong>and</strong> sought outprofessional maternity care only for complications.Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, health facilities had greater resourcesthan was perceived by the community. A review ofhealth facilities found that district <strong>and</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>cialhospitals had functional operat<strong>in</strong>g theatres with thenecessary equipment to h<strong>and</strong>le surgery, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gCaesarean-sections. The majority of health facilities(78%) had a referral system with appropriatelogistics <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g either a vehicle or easy accessto hired transportation.Use of traditional birthattendantsMost traditional birth attendants were elder womenwho had resided <strong>in</strong> the community for at least20 years. In general, these women were illiterate,<strong>and</strong> only half had received any type of formaltra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. The traditional birth attendants<strong>in</strong>terviewed believed that they were highly soliciteddue to their quality services, their good childbirthskills, <strong>and</strong> their low-cost or free services. Dur<strong>in</strong>gthe course of discussion with the traditional birthattendants, nearly all affirmed that they referredtheir patients to a health facility, be it a healthcentre or a district hospital, if they wereexperienc<strong>in</strong>g a difficult labour. When questionedabout the nature of a difficult labour, thetraditional birth attendants cited prolonged labour,maternal exhaustion, <strong>and</strong> abnormal presentationof the foetus.Community members highlighted reasons for us<strong>in</strong>ga traditional birth attendant. Lack of money <strong>and</strong>the long distance made health facility accessdifficult. The traditional birth attendant was oftenknown to the family. Some community membersstated that health facilities did not have properequipment for women <strong>in</strong> labour <strong>and</strong> that healthproviders needed improved communication skills.Some husb<strong>and</strong>s objected to male health providerssee<strong>in</strong>g their spouses unclothed.Conversely, some community members accused thetraditional birth attendants of be<strong>in</strong>g responsiblefor certa<strong>in</strong> avoidable complications. Interviewees<strong>in</strong>dicated that traditional birth attendants did noteasily accept that a labour complication mightneed professional assistance. Nevertheless,traditional birth attendants hold a place ofprom<strong>in</strong>ence <strong>in</strong> the community with regard topregnancy <strong>and</strong> childbirth.20Liv<strong>in</strong>g Testimony