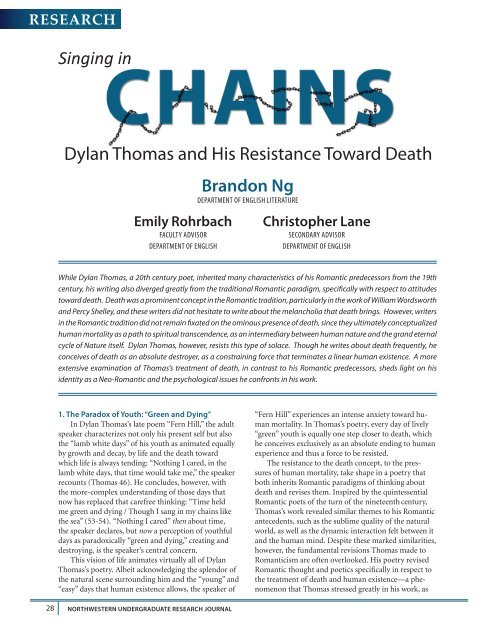

RESEARCHSinging inDylan Thomas and His Resistance Toward DeathEmily RohrbachFACULTY ADVISORDEPARTMENT OF ENGLISHBrandon NgDEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATUREChristopher LaneSECONDARY ADVISORDEPARTMENT OF ENGLISHWhile Dylan Thomas, a 20th century poet, inherited many characteristics of his Romantic predecessors from the 19thcentury, his writing also diverged greatly from the traditional Romantic paradigm, specifically with respect to attitudestoward death. Death was a prominent concept in the Romantic tradition, particularly in the work of William Wordsworthand Percy Shelley, and these writers did not hesitate to write about the melancholia that death brings. However, writersin the Romantic tradition did not remain fixated on the ominous presence of death, since they ultimately conceptualizedhuman mortality as a path to spiritual transcendence, as an intermediary between human nature and the grand eternalcycle of Nature itself. Dylan Thomas, however, resists this type of solace. Though he writes about death frequently, heconceives of death as an absolute destroyer, as a constraining force that terminates a linear human existence. A moreextensive examination of Thomas’s treatment of death, in contrast to his Romantic predecessors, sheds light on hisidentity as a Neo-Romantic and the psychological issues he confronts in his work.1. The Paradox of Youth: “Green and Dying”In Dylan Thomas’s late poem “Fern Hill,” the adultspeaker characterizes not only his present self but alsothe “lamb white days” of his youth as animated equallyby growth and decay, by life and the death towardwhich life is always tending: “Nothing I cared, in thelamb white days, that time would take me,” the speakerrecounts (Thomas 46). He concludes, however, withthe more-complex understanding of those days thatnow has replaced that carefree thinking: “Time heldme green and dying / Though I sang in my chains likethe sea” (53-54). “Nothing I cared” then about time,the speaker declares, but now a perception of youthfuldays as paradoxically “green and dying,” creating anddestroying, is the speaker’s central concern.This vision of life animates virtually all of DylanThomas’s poetry. Albeit acknowledging the splendor ofthe natural scene surrounding him and the “young” and“easy” days that human existence allows, the speaker of“Fern Hill” experiences an intense anxiety toward humanmortality. In Thomas’s poetry, every day of lively“green” youth is equally one step closer to death, whichhe conceives exclusively as an absolute ending to humanexperience and thus a force to be resisted.The resistance to the death concept, to the pressuresof human mortality, take shape in a poetry thatboth inherits Romantic paradigms of thinking aboutdeath and revises them. Inspired by the quintessentialRomantic poets of the turn of the nineteenth century,Thomas’s work revealed similar themes to his Romanticantecedents, such as the sublime quality of the naturalworld, as well as the dynamic interaction felt between itand the human mind. Despite these marked similarities,however, the fundamental revisions Thomas made toRomanticism are often overlooked. His poetry revisedRomantic thought and poetics specifically in respect tothe treatment of death and human existence—a phenomenonthat Thomas stressed greatly in his work, as28 NORTHWESTERN UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL

RESEARCHwell as a topic about which Wordsworth and Shelley,in particular, wrote extensively. Although each of thesepoets initially expressed melancholia about the prospectof death, in the poetry of Wordsworth and Shelley thespeakers ultimately assuage their feelings of lament byreinterpreting death as a path to spiritual transcendence.Thomas, on the other hand, refuses this type of solace.Instead, he conceptualized death exclusively as an evil,constraining force that ultimately does nothing morethan reduce human beings to their material existence.Moreover, Thomas conceived of human existence in alinear fashion, beginning with birth and ending withdeath, from which no transcendence can evade. It isthis attitude toward human mortality that constitutes akey divergence from the Romantic paradigm.2. Establishing the Romantic ParadigmM. H. Abrams summarizes the Romantic explorationof the relationship between the human mind andnature in Natural Supernaturalism, in the context ofdiscussing Wordsworth’s The Prelude and Milton’s ParadiseLost: “The vision is that of the awesome depths andheight of the human mind, and of the power of thatmind as in itself adequate, by consummating a holymarriage with the external universe, to create out of theworld of all of us, in a quotidian and recurrent miracle,a new world which is the equivalent of paradise” (28).In this sense, the intercourse between human beings andthe natural world is the path through which the mindattains “awesome depths and height.” As Abrams asserts,through this “holy marriage,” Wordsworth envisionsthat a sense of “paradise” will ensue in which mankindis capable of reaching its full potential, its full capacityfor thought and feeling. Abrams writes that throughthe “culminating and procreative marriage betweenmind and nature,” humans attain a more transcendentexistence. Marriage, or “the song,” as Wordsworth callsit, “will be an evangel to effect a spiritual resurrectionamong mankind—it will ‘arouse the sensual from theirsleep / Of death’—merely by showing what lies withinany man’s power to accomplish, as he is here and now”(qtd. in Abrams 27). In this sense, Abrams avers thatthrough merging with the natural world, which is somuch greater than one man, humankind can triumphover death and achieve a sense of rebirth and eternal life.Romantic preoccupation with the relationshipbetween humanity and the natural world resurfacedin the twentieth century, as a new generation of writersbecame interested once more in the concerns ofRomanticism. In fact, the central themes of Romanticismhave recurred over and again, as Jonathan Batepoignantly summarizes: “Romanticism has remained aliving legacy because, like a fit Darwinian organism, ithas proved singularly adaptable to a succession of newenvironments, whether Victorian medievalism […] orthe counter-reading of 1980s ideologism” (Bate 436).VOLUME 7, 2011-2012The rebirth of Romanticism in the twentieth century,which critics often call “Neo-Romanticism,” representsthis newfound inheritance of the Romantic tradition,but also reflects the changing, modern social and intellectualcontext in which this new generation of writersfound itself. As Abrams asserts, though works may offera “drastically altered perspective on man and natureand human life,” it is through this exploration that they“continue to embody Romantic innovations in ideasand design” (Abrams 32; see Ramazani 1-2). In thissense, Neo-Romanticism is a useful term for conceptualizingsome twentieth century-writers’ shared fascinationwith the human mind and its relationship to thenatural world.Thomas inherited his fascination with nature fromhis Romantic precursors, for through his poetry he freelyelaborates on the complex relationship between humanexistence and the natural world. But even so, though heworks within the paradigm of pondering the relationbetween human nature and nature, he also distinguisheshimself from the Romantics by conceiving of death notas a threshold to eternity, but as the decisive endpointof a linear human trajectory, a viewpoint embraced verymuch by classicism. T. E. Hulme, a twentieth-centurymodernist, in his 1911 essay “Romanticism and Classicism,”remarks on the fundamental difference betweenthe two schools of thought, albeit harshly denouncingRomanticism in the process: “Here is the root of allRomanticism: that man, the individual, is an infinitereservoir of possibilities […] One can define the classicalquite clearly as the exact opposite of this. Man is anextraordinarily fixed and limited animal whose nature isabsolutely constant” (115).Arguably in few places is the manifestation of man’srestrictive and bounded existence more pronouncedthan in Thomas’s poetry, which attributes the “fixed”and “limited” nature of human existence to the formidableforce of death that all humans must face.Although the speaker in “Fern Hill” tries to break theinescapable cycle of human life by reminiscing on thebeautiful “green” and “golden” days of his youth thatleave him singing at the end of the poem, ultimately heis unable to escape his pending fate—the force of deaththat leaves him in chains.To Hulme, it is precisely this inescapability, thisinevitability of man’s limitations that characterizes aclassical conception of human nature. Although humanbeings may see glimpses of a transcendent path to breakfree from their bounded existence, he argues that classicistsaccept that this path does not—and never will—exist. He remarks, “What I mean by classical in verse,then, is this. That even in the most imaginative flightsthere is always a holding back, a reservation. The classicalpoet never forgets this finiteness, this limit of man[…] He may jump, but he always returns back; he neverflies away into the circumambient gas” (119). Through-NORTHWESTERN UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL29