ITP in Children: Pathophysiology and Current Treatment Approaches

ITP in Children: Pathophysiology and Current Treatment Approaches

ITP in Children: Pathophysiology and Current Treatment Approaches

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

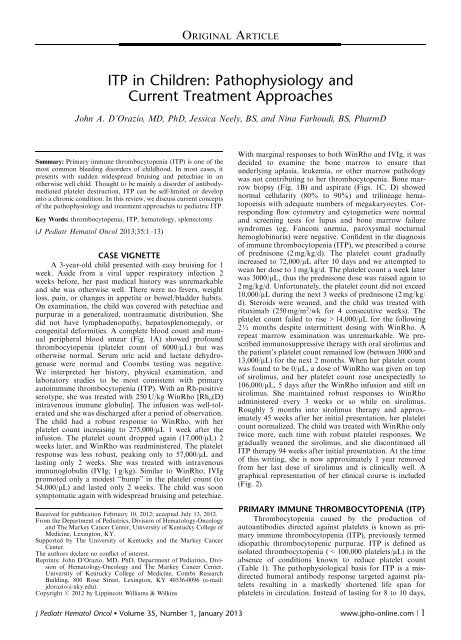

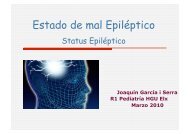

ORIGINAL ARTICLE<strong>ITP</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Children</strong>: <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>Current</strong> <strong>Treatment</strong> <strong>Approaches</strong>John A. D’Orazio, MD, PhD, Jessica Neely, BS, <strong>and</strong> N<strong>in</strong>a Farhoudi, BS, PharmDSummary: Primary immune thrombocytopenia (<strong>ITP</strong>) is one of themost common bleed<strong>in</strong>g disorders of childhood. In most cases, itpresents with sudden widespread bruis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> petechiae <strong>in</strong> anotherwise well child. Thought to be ma<strong>in</strong>ly a disorder of antibodymediatedplatelet destruction, <strong>ITP</strong> can be self-limited or develop<strong>in</strong>to a chronic condition. In this review, we discuss current conceptsof the pathophysiology <strong>and</strong> treatment approaches to pediatric <strong>ITP</strong>.Key Words: thrombocytopenia, <strong>ITP</strong>, hematology, splenectomy(J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35:1–13)CASE VIGNETTEA 3-year-old child presented with easy bruis<strong>in</strong>g for 1week. Aside from a viral upper respiratory <strong>in</strong>fection 2weeks before, her past medical history was unremarkable<strong>and</strong> she was otherwise well. There were no fevers, weightloss, pa<strong>in</strong>, or changes <strong>in</strong> appetite or bowel/bladder habits.On exam<strong>in</strong>ation, the child was covered with petechiae <strong>and</strong>purpurae <strong>in</strong> a generalized, nontraumatic distribution. Shedid not have lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, orcongenital deformities. A complete blood count <strong>and</strong> manualperipheral blood smear (Fig. 1A) showed profoundthrombocytopenia (platelet count of 6000/mL) but wasotherwise normal. Serum uric acid <strong>and</strong> lactate dehydrogenasewere normal <strong>and</strong> Coombs test<strong>in</strong>g was negative.We <strong>in</strong>terpreted her history, physical exam<strong>in</strong>ation, <strong>and</strong>laboratory studies to be most consistent with primaryautoimmune thrombocytopenia (<strong>ITP</strong>). With an Rh-positiveserotype, she was treated with 250 U/kg W<strong>in</strong>Rho [Rh o (D)<strong>in</strong>travenous immune globul<strong>in</strong>]. The <strong>in</strong>fusion was well-tolerated<strong>and</strong> she was discharged after a period of observation.The child had a robust response to W<strong>in</strong>Rho, with herplatelet count <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g to 275,000/mL 1 week after the<strong>in</strong>fusion. The platelet count dropped aga<strong>in</strong> (17,000/mL) 2weeks later, <strong>and</strong> W<strong>in</strong>Rho was readm<strong>in</strong>istered. The plateletresponse was less robust, peak<strong>in</strong>g only to 57,000/mL <strong>and</strong>last<strong>in</strong>g only 2 weeks. She was treated with <strong>in</strong>travenousimmunoglobul<strong>in</strong> (IVIg; 1 g/kg). Similar to W<strong>in</strong>Rho, IVIgpromoted only a modest “bump” <strong>in</strong> the platelet count (to54,000/mL) <strong>and</strong> lasted only 2 weeks. The child was soonsymptomatic aga<strong>in</strong> with widespread bruis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> petechiae.Received for publication February 10, 2012; accepted July 13, 2012.From the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Hematology-Oncology<strong>and</strong> The Markey Cancer Center, University of Kentucky College ofMedic<strong>in</strong>e, Lex<strong>in</strong>gton, KY.Supported by The University of Kentucky <strong>and</strong> the Markey CancerCenter.The authors declare no conflict of <strong>in</strong>terest.Repr<strong>in</strong>ts: John D’Orazio, MD, PhD, Department of Pediatrics, Divisionof Hematology-Oncology <strong>and</strong> The Markey Cancer Center,University of Kentucky College of Medic<strong>in</strong>e, Combs ResearchBuild<strong>in</strong>g, 800 Rose Street, Lex<strong>in</strong>gton, KY 40536-0096 (e-mail:jdorazio@uky.edu).Copyright r 2012 by Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>sWith marg<strong>in</strong>al responses to both W<strong>in</strong>Rho <strong>and</strong> IVIg, it wasdecided to exam<strong>in</strong>e the bone marrow to ensure thatunderly<strong>in</strong>g aplasia, leukemia, or other marrow pathologywas not contribut<strong>in</strong>g to her thrombocytopenia. Bone marrowbiopsy (Fig. 1B) <strong>and</strong> aspirate (Figs. 1C, D) showednormal cellularity (80% to 90%) <strong>and</strong> tril<strong>in</strong>eage hematopoeisiswith adequate numbers of megakaryocytes. Correspond<strong>in</strong>gflow cytometry <strong>and</strong> cytogenetics were normal<strong>and</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g tests for lupus <strong>and</strong> bone marrow failuresyndromes (eg, Fanconi anemia, paroxysmal nocturnalhemoglob<strong>in</strong>uria) were negative. Confident <strong>in</strong> the diagnosisof immune thrombocytopenia (<strong>ITP</strong>), we prescribed a courseof prednisone (2 mg/kg/d). The platelet count gradually<strong>in</strong>creased to 72,000/mL after 10 days <strong>and</strong> we attempted towean her dose to 1 mg/kg/d. The platelet count a week laterwas 3000/mL, thus the prednisone dose was raised aga<strong>in</strong> to2 mg/kg/d. Unfortunately, the platelet count did not exceed10,000/mL dur<strong>in</strong>g the next 3 weeks of prednisone (2 mg/kg/d). Steroids were weaned, <strong>and</strong> the child was treated withrituximab (250 mg/m 2 /wk for 4 consecutive weeks). Theplatelet count failed to rise >14,000/mL for the follow<strong>in</strong>g2½ months despite <strong>in</strong>termittent dos<strong>in</strong>g with W<strong>in</strong>Rho. Arepeat marrow exam<strong>in</strong>ation was unremarkable. We prescribedimmunosuppressive therapy with oral sirolimus <strong>and</strong>the patient’s platelet count rema<strong>in</strong>ed low (between 3000 <strong>and</strong>13,000/mL) for the next 2 months. When her platelet countwas found to be 0/mL, a dose of W<strong>in</strong>Rho was given on topof sirolimus, <strong>and</strong> her platelet count rose unexpectedly to106,000/mL, 5 days after the W<strong>in</strong>Rho <strong>in</strong>fusion <strong>and</strong> still onsirolimus. She ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed robust responses to W<strong>in</strong>Rhoadm<strong>in</strong>istered every 3 weeks or so while on sirolimus.Roughly 5 months <strong>in</strong>to sirolimus therapy <strong>and</strong> approximately45 weeks after her <strong>in</strong>itial presentation, her plateletcount normalized. The child was treated with W<strong>in</strong>Rho onlytwice more, each time with robust platelet responses. Wegradually weaned the sirolimus, <strong>and</strong> she discont<strong>in</strong>ued all<strong>ITP</strong> therapy 94 weeks after <strong>in</strong>itial presentation. At the timeof this writ<strong>in</strong>g, she is now approximately 1 year removedfrom her last dose of sirolimus <strong>and</strong> is cl<strong>in</strong>ically well. Agraphical representation of her cl<strong>in</strong>ical course is <strong>in</strong>cluded(Fig. 2).PRIMARY IMMUNE THROMBOCYTOPENIA (<strong>ITP</strong>)Thrombocytopenia caused by the production ofautoantibodies directed aga<strong>in</strong>st platelets is known as primaryimmune thrombocytopenia (<strong>ITP</strong>), previously termedidiopathic thrombocytopenic purpurae. <strong>ITP</strong> is def<strong>in</strong>ed asisolated thrombocytopenia (< 100,000 platelets/mL) <strong>in</strong> theabsence of conditions known to reduce platelet count(Table 1). The pathophysiological basis for <strong>ITP</strong> is a misdirectedhumoral antibody response targeted aga<strong>in</strong>st plateletsresult<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a markedly shortened life span forplatelets <strong>in</strong> circulation. Instead of last<strong>in</strong>g for 8 to 10 days,J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 2013 www.jpho-onl<strong>in</strong>e.com | 1

D’Orazio et al J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 2013ABCDFIGURE 1. Representative hematologic images from the patient described <strong>in</strong> the cl<strong>in</strong>ical vignette. Shown are the peripheral bloodsmear (A), core bone marrow (BM) biopsy (B), <strong>and</strong> BM aspirates (C <strong>and</strong> D) from the patient 5 weeks <strong>in</strong>to her cl<strong>in</strong>ical course. Note thepaucity of platelets (white triangle <strong>in</strong> A) <strong>in</strong> the peripheral blood but adequate numbers of megakaryocytes (yellow triangles <strong>in</strong> B, C, <strong>and</strong>D) <strong>in</strong> a marrow of adequate cellularity <strong>and</strong> heterogeneity, consistent with peripheral destruction of mature platelets. All images are400 magnification.circulat<strong>in</strong>g platelets persist only for a few hours <strong>in</strong> patientswith <strong>ITP</strong> because they are rapidly cleared once coated withantibody. 6 Interference with production of platelets mayalso occur <strong>in</strong> <strong>ITP</strong> through suppression of megakaryocyteproduction <strong>in</strong> the marrow, 7 therefore, <strong>ITP</strong> is a mixed disorderof destruction <strong>and</strong> production. As new platelet300Platelet count (x10 3 ) per mL25020015010050BMPrednisoneRituximabBMSirolimus(1 mg/m 2 /d)0.5 mg/m 2 /dPatient asymptomatic1 year after sirolimus wean00 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95(1 yr later)W W I W W W W W W W WWWTime s<strong>in</strong>ce diagnosis (weeks)FIGURE 2. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical course of the patient <strong>in</strong> the vignette, shown as platelet count versus time s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong>itial presentation with thrombocytopenia.Shown are various diagnostic <strong>and</strong> therapeutic <strong>in</strong>terventions: bone marrow exam<strong>in</strong>ation (BM), prednisone (2 mg/kg/d withtaper), W<strong>in</strong>Rho (W) (250 U/kg/dose) <strong>in</strong>travenous immunoglobul<strong>in</strong> (IVIg; 1 g/kg/dose), rituximab (250 U/kg/wk 4 consecutive weeks).2 | www.jpho-onl<strong>in</strong>e.com r 2012 Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s

J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 2013<strong>ITP</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Children</strong>:<strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Current</strong> <strong>Treatment</strong> <strong>Approaches</strong>TABLE 1. Differential Diagnosis of Thrombocytopenia <strong>in</strong><strong>Children</strong>PseudothrombocytopeniaGestational/neonatalcausesCongenital or <strong>in</strong>heriteddisordersInfectious etiologiesImpaired thrombopoeisis(marrow failure)Giant platelet disordersMalignancyPlatelet sequestrationMedication-<strong>in</strong>ducedNutritional (folic aciddeficiency vitam<strong>in</strong> B 12deficiency)Consumptive processesEDTA-<strong>in</strong>duced platelet clump<strong>in</strong>gMaternal preeclampsia, HELLPsyndromeErythroblastosis fetalisMaternal drug <strong>in</strong>gestion (eg, thiazides)Neonatal alloimmunethrombocytopeniaThrombocytopenia absent radiussyndromeAmegakaryocytosis/congenitalthrombocytopeniaWiskott-Aldrich syndrome;May-Heggl<strong>in</strong> anomalySepsisCongenital TORCH <strong>in</strong>fection(especially rubella or CMV)Viral <strong>in</strong>fection (EBV, VZV, <strong>in</strong>fluenza,rubella, CMV, HIV, hepatitisviruses, others)Rickettsial diseasesToxic shock syndromeTuberculosisHelicobacter pylori [associated withimmune thrombocytopenia (<strong>ITP</strong>)]Histoplasmosis, toxoplasmosisAplastic anemiaFanconi anemiaMegakaryocytic aplasiaParoxysmal nocturnal hematuriaMyelofibrosisMyelodysplastic syndromesOsteopetrosisThrombocytopenia absent radiussyndromeWiskott-Aldrich syndromeIoniz<strong>in</strong>g radiation exposureCyclic thrombocytopeniaPoststem cell transplantationMay-Heggl<strong>in</strong> anomalyBernard-Soulier syndromeLeukemiasLymphoproliferative disordersMyelophthisis (marrow <strong>in</strong>filtration)Hypersplenism (eg, lysosomal storagediseases)SarcoidosisChemotherapy-<strong>in</strong>duced marrowsuppressionHepar<strong>in</strong>-<strong>in</strong>duced thrombocytopeniaDrug-<strong>in</strong>duced <strong>ITP</strong>—valproic acid,chloramphenicol, qu<strong>in</strong>id<strong>in</strong>e,sulfonamides, <strong>in</strong>domethac<strong>in</strong>,thiazides, rifamp<strong>in</strong>, estrogens,othersInadequate dietary <strong>in</strong>takeBacterial overgrowthSurgical resection of stomach or smallbowelShort gut syndromeCrohn diseasePernicious anemiaKassabach-Merritt syndrome (giantcavernous hemangioma)Dissem<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong>travascularcoagulationTABLE 1. (cont<strong>in</strong>ued)DilutionalCollagen VasculardisordersImmune-mediatedOtherThrombotic thrombocytopenicpurpurae (TTP)Hemolytic uremic syndromeVasculitisHemophagocytic syndromesEnvenomation—snake bite, spiderbite, scorpion st<strong>in</strong>g, etc.Severe burn (Z10% body surface area)Type 2B von Willebr<strong>and</strong> disease(mutant VWF with <strong>in</strong>creased aff<strong>in</strong>ityfor platelet glycoprote<strong>in</strong> Ib)Abnormal blood flow/shear(catheterization, prostheses,artificial valves)Purpura fulm<strong>in</strong>ansExtracorporeal circulationMassive red cell transfusionHemodialysisSystemic lupus erythematosusAntiphospholipid syndromeRheumatoid arthritisNeonatal alloimmunethrombocytopeniaMaternal <strong>ITP</strong> with trans-placentaltransfer of antiplatelet IgG to fetusPrimary auto-<strong>ITP</strong>: acute or chronicEvans syndrome (concomitant <strong>ITP</strong><strong>and</strong> autoimmunehemolytic anemia or autoimmuneneutropenia)Post-transfusion purpuraePost-vacc<strong>in</strong>ation (especially MMR)Common variable immune deficiencyTransfusion relatedLiver failure, thrombopoeit<strong>in</strong>deficiencyAlport syndromeHyperthermia, hypothermiaFor primary <strong>ITP</strong> to be diagnosed, disorders known to be associated withsecondary thrombocytopenia must first be reasonably excluded. Please notethat this is an <strong>in</strong>complete list <strong>and</strong> although diseases have been organized <strong>in</strong>tobroad categories, many can lower platelet count by Z1 mechanism. 1–5CMV <strong>in</strong>dicates cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epste<strong>in</strong>-Barr virus; EDTA, ethylenediam<strong>in</strong>etetraaceticacid; HELLP, hemolysis, elevated Liver enzymes<strong>and</strong> low platelet count; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; TORCH,toxoplasmosis, other, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus-2;VZV, varicella zoster virus.production cannot keep pace with peripheral clearance,total number of circulat<strong>in</strong>g platelets drops <strong>and</strong> symptomsof thrombocytopenia ensue. Circulat<strong>in</strong>g platelets <strong>in</strong> <strong>ITP</strong>patients, although few <strong>in</strong> number, tend to be particularlyeffective at hemostasis, perhaps because most will have beenrecently released from the marrow <strong>and</strong> are fresh, large, <strong>and</strong>granular. As a result, <strong>ITP</strong> patients are far less likely to haveserious bleed<strong>in</strong>g than patients with similarly low plateletcounts caused by other processes such as marrow failure.<strong>ITP</strong> can be diagnosed only when other causes of thrombocytopeniashave been considered <strong>and</strong> reasonablyexcluded (Table 1). The marrow is typically normal <strong>in</strong> <strong>ITP</strong>, 8re<strong>in</strong>forc<strong>in</strong>g the concept that <strong>ITP</strong> is primarily a process ofpremature platelet destruction rather than one of <strong>in</strong>sufficientor impaired platelet production. The American Societyof Hematology suggests, however, that a bone marrowexam<strong>in</strong>ation is not rout<strong>in</strong>ely <strong>in</strong>dicated to establish ther 2012 Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s www.jpho-onl<strong>in</strong>e.com | 3

D’Orazio et al J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 2013beyond then with or without anti-immune–directedtherapy. 33PATHOPHYSIOLOGYA groundbreak<strong>in</strong>g experiment performed <strong>in</strong> 1950proved beyond doubt that <strong>ITP</strong> is a humoral disease associatedwith premature destruction of circulat<strong>in</strong>g platelets.In a cl<strong>in</strong>ical trial that could never be carried out today, DrsWilliam Harr<strong>in</strong>gton <strong>and</strong> James Holl<strong>in</strong>gsworth, 2 medicalhematology fellows <strong>in</strong> St Louis, <strong>in</strong>jected healthy subjects(<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Harr<strong>in</strong>gton himself) with plasma derived frompatients suffer<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>ITP</strong>. In each of 35 separate trials,plasma from patients with <strong>ITP</strong> (but not from normal controls)profoundly lowered the recipient’s circulat<strong>in</strong>g plateletcount with<strong>in</strong> 30 to 60 m<strong>in</strong>utes with persistence for up to 7days. To be sure the humoral factor responsible for <strong>ITP</strong>caused destruction of platelets rather than <strong>in</strong>hibition oftheir formation, recipients also underwent bone marrowexam<strong>in</strong>ations—<strong>in</strong> each case no abnormalities <strong>in</strong> either thenumber or appearance of megakaryocytes was found. 34,35We now know that the circulat<strong>in</strong>g factor responsible for<strong>ITP</strong> is IgG that b<strong>in</strong>ds platelets <strong>and</strong> leads to their prematuredestruction. 36 Platelet antigens recognized <strong>in</strong> <strong>ITP</strong> <strong>in</strong>cludemembrane glycoprote<strong>in</strong>s Ia/IIa, IIIa, Ib, IIb, <strong>and</strong> IX. 37–39Regardless of the antigen targeted, b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g of IgG to theplatelets encourages opsonization <strong>and</strong> phagocytosis byreticuolendothelial cells primarily <strong>in</strong> the spleen. As a result,the life span of circulat<strong>in</strong>g platelets, normally 8 to 10 days,is profoundly reduced to a matter of a few hours. 35 Thus,<strong>ITP</strong> clearly is associated with premature clearance of platelets<strong>in</strong> the periphery. Recent evidence suggests that plateletunderproduction may also contribute to <strong>ITP</strong>. Autoantibodiesmay b<strong>in</strong>d megakaryocytes <strong>in</strong> the marrow <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>terfere with their survival or differentiation. 7,40 In addition,there is evidence that <strong>ITP</strong> is associated with impairedhepatic production of thrombopoeit<strong>in</strong>, the chief stimulantof megakaryocyte proliferation <strong>and</strong> platelet production. 41This basic underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of the various underly<strong>in</strong>g mechanismsof disease at play <strong>in</strong> <strong>ITP</strong> expla<strong>in</strong>s our currenttreatment approaches to <strong>ITP</strong>: (1) <strong>in</strong>terference with antibodyproduction; (2) <strong>in</strong>hibition of F c receptor-mediated opsonizationby splenic macrophages; (3) immunosuppression;<strong>and</strong> (4) stimulation of thrombopoeisis <strong>in</strong> the marrow.PSYCHOSOCIAL IMPACT OF THE DISEASEThe psychosocial burdens of <strong>ITP</strong> on patients <strong>and</strong> theirfamilies can be significant, especially when <strong>ITP</strong> is longlast<strong>in</strong>g.Parental concerns over serious bleed<strong>in</strong>g, frequentblood test<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>fusions, activity restrictions, <strong>and</strong> medicationside effects are major stressors that accompany thediagnosis. Prolonged restriction of normal activities ofchildhood can have significant impact study by Klaassenet al 42 found that treat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>ITP</strong> patients with romiplostim, athrombopoeit<strong>in</strong> agonist, significantly reduced parentalpsychological burden, presumably because parents wereless stressed about potential bleed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> their children afterplatelet counts were raised. In 1 analysis of over 1000 adult<strong>ITP</strong> patients <strong>and</strong> over 1000 non-<strong>ITP</strong> controls, <strong>ITP</strong> patientsscored significantly worse on a variety of lifestyle measures,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g 7 of 8 SF (short form)-36 quality of life assessmentdoma<strong>in</strong>s, the Physical <strong>and</strong> Mental Summary score,<strong>and</strong> the EQ (EuroQol)-5D visual analog scale. 43 Anotherstudy found that the health-related quality of life <strong>in</strong> <strong>ITP</strong>patients was even worse than patients with cancer. 44Therefore, although <strong>ITP</strong> can be considered to be a “benign”hematologic disorder, it is associated with significant psychologicalstress. To provide the most comprehensive careto children with <strong>ITP</strong> <strong>and</strong> their families, it is critical toexplore the psychosocial impacts of the diagnosis onpatients <strong>and</strong> their families.THROMBOCYTOPENIC ACTIVITY PRECAUTIONSOne of the most challeng<strong>in</strong>g aspects to the managementof a child with <strong>ITP</strong> is restrict<strong>in</strong>g participation <strong>in</strong>normal play <strong>and</strong> sports activities because of concerns overbleed<strong>in</strong>g risk. Incidence of severe hemorrhage is actuallyrare <strong>in</strong> uncomplicated childhood <strong>ITP</strong>, <strong>and</strong> few <strong>in</strong>ternalbleeds occur unless a significant trauma or <strong>in</strong>jury occurswhile the patient is severely thrombocytopenic. 45 Intracranialhemorrhage occurs <strong>in</strong> only 1 <strong>in</strong> a thous<strong>and</strong> childrendiagnosed with <strong>ITP</strong>. 12 Nonetheless, many practitioners feelthat a “common sense” approach should be adopted withregard to physical activities dur<strong>in</strong>g periods of thrombocytopenia.In cases where the <strong>ITP</strong> persists for many weeks ormonths, activity limitations must be balanced with anappreciation of the many consequences of “shelter<strong>in</strong>g” achild with chronic <strong>ITP</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g decondition<strong>in</strong>g, weightga<strong>in</strong>, <strong>and</strong> sick child syndrome. There is great variation <strong>in</strong>how patients with <strong>ITP</strong> are counseled with respect to activitylimitations. Some pediatric hematologists take the view thatalmost any supervised sports activity (with the possibleexception of box<strong>in</strong>g) can be undertaken safely as long asproper precautions are taken (eg, wear<strong>in</strong>g a helmet whenbatt<strong>in</strong>g or bicycl<strong>in</strong>g) <strong>and</strong> as long as the patient <strong>and</strong> parentsclearly underst<strong>and</strong> the risks of tak<strong>in</strong>g part <strong>in</strong> such activities.Other cl<strong>in</strong>icians advise aga<strong>in</strong>st participation <strong>in</strong> any activityassociated with a significant risk of trauma (especially head<strong>in</strong>jury) when platelet counts fall below 50,000 to 75,000/mL.For toddlers <strong>and</strong> preschool children, this might meanavoid<strong>in</strong>g stairs <strong>and</strong> other climb<strong>in</strong>g structures such as playgroundequipment or sleep<strong>in</strong>g on the top bunk bed, etc.).For older children <strong>and</strong> adolescents, thrombocytopeniarestrictions often <strong>in</strong>volve avoid<strong>in</strong>g certa<strong>in</strong> sports <strong>and</strong> leisureactivities (Table 3). Regardless of approach, medicationsthat <strong>in</strong>hibit platelet function, most notably nonsteroidalanti-<strong>in</strong>flammatory drugs <strong>and</strong> aspir<strong>in</strong>, should be avoidedwhile patients are thrombocytopenic.THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONSThe <strong>ITP</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g group of the American Society ofHematology recently published updated evidenced-basedpractice guidel<strong>in</strong>e for the management of <strong>ITP</strong>. Regard<strong>in</strong>gchildren, the committee suggested that observation alone isappropriate for pediatric <strong>ITP</strong> patients with sk<strong>in</strong> manifestations(bruis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> petechiae) only <strong>and</strong> no other bleed<strong>in</strong>g,regardless of platelet count. 1 Recent data <strong>in</strong>dicate that this“watch <strong>and</strong> wait” approach may be used <strong>in</strong> as many as 20%of children with <strong>ITP</strong>. 49 In practice, however, most hematologists<strong>and</strong> families opt to treat children with <strong>ITP</strong>, especially<strong>in</strong> the sett<strong>in</strong>g of a platelet count

J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 2013<strong>ITP</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Children</strong>:<strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Current</strong> <strong>Treatment</strong> <strong>Approaches</strong>TABLE 3. Profile of Physical Activities <strong>and</strong> Their Risk of Trauma toParticipantsFull contactsportsLimitedcontactsportsNoncontactsportsPhysical activities <strong>in</strong>which eitherdeliberate or<strong>in</strong>cidentalsignificant physicalimpact between oron participants isallowed for with<strong>in</strong>the rules of the game<strong>and</strong> therefore can beexpected to occurMost care providerswould advise thatthrombocytopenicpatients avoid suchactivitiesActivities <strong>in</strong> which therules are specificallydesigned to prevent<strong>in</strong>tentional orun<strong>in</strong>tentionalcontact betweenparticipants,however, significantcontact betweenplayers or betweena player <strong>and</strong>sport<strong>in</strong>g equipmentcan still occurdur<strong>in</strong>g participationMany care providerswould advise thattheir thrombocytopenicpatientstake precautions orabsta<strong>in</strong> fromparticipation tom<strong>in</strong>imize risk oftrauma <strong>and</strong> head<strong>in</strong>jurySports that limit thechances for traumaby separat<strong>in</strong>gparticipantsSuch activities <strong>in</strong>clude<strong>and</strong> are usuallydeemed as safe forthrombocytopenicpatientsAmerican footballAll-terra<strong>in</strong> vehicle ormotorcycle rac<strong>in</strong>gBox<strong>in</strong>gDiv<strong>in</strong>g (competitiveor high)Extreme sportsHang glid<strong>in</strong>g or skydiv<strong>in</strong>gHockey (either ice,field, or street)Horseback rid<strong>in</strong>gKickbox<strong>in</strong>gLacrosseMartial arts, karate,tae kwondoRock climb<strong>in</strong>gRugbyWater poloWrestl<strong>in</strong>gBaseballBasketballCheerlead<strong>in</strong>gCycl<strong>in</strong>gDanc<strong>in</strong>gGymnasticsRacquetballRollerblad<strong>in</strong>gRunn<strong>in</strong>gSki<strong>in</strong>gSnowboard<strong>in</strong>gSoccerSoftballSquashSurf<strong>in</strong>gUltimate frisbeeAerobicsBowl<strong>in</strong>gCricketCurl<strong>in</strong>gGolfJogg<strong>in</strong>gRow<strong>in</strong>gRunn<strong>in</strong>gSwimm<strong>in</strong>gTennisVolleyballWalk<strong>in</strong>gYogaPhysical activities can be divided <strong>in</strong>to 3 groups based on the degree of<strong>in</strong>terpersonal contact <strong>and</strong>/or risk of trauma <strong>in</strong>volved. In general, thrombocytopenicpatients should probably avoid those activities with significant riskof trauma. 18,46–48as transfused platelets are usually rapidly cleared from thecirculation <strong>and</strong> autoantibodies rapidly reappear <strong>in</strong> theserum after plasmapheresis. 51–53MEDICAL MANAGEMENTIn general, therapy for children with chronic <strong>ITP</strong> tendsto be <strong>in</strong>dividualized accord<strong>in</strong>g to a variety of factors<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g efficacy, schedul<strong>in</strong>g, toxicity, cost, <strong>and</strong> preferencesof the patient, parents, <strong>and</strong> hematologist. Therapeutic<strong>in</strong>terventions for <strong>ITP</strong> can be conceptualized as “front-l<strong>in</strong>e”or “second-l<strong>in</strong>e” approaches (Table 4). Each patient’s <strong>ITP</strong>course is unique, <strong>and</strong> once therapy has begun, plateletcounts are generally monitored overtime to assess response.Therapeutic response criteria have been st<strong>and</strong>ardized(Table 5). For some patients, only 1 treatment will berequired before their <strong>ITP</strong> resolves, whereas for others (likeour patient), repeated treatments may be needed over time.Presumably, the severity <strong>and</strong> course of thrombocytopeniawill be determ<strong>in</strong>ed by the strength <strong>and</strong> longevity of theantiplatelet immune response. In practice, practitionersmust be somewhat flexible <strong>in</strong> their approach, <strong>and</strong> may turnfrom one therapy to another to optimize treatment for theirparticular patient. If platelets do not <strong>in</strong>crease after an<strong>in</strong>tervention, then either further therapy may be required(eg, a second dose of IVIg), or the diagnosis of <strong>ITP</strong> shouldbe reevaluated. For the typical child who presents withacute <strong>ITP</strong>, front-l<strong>in</strong>e management <strong>in</strong>cludes IVIg, a shortcourse of corticosteroids or W<strong>in</strong>Rho (Anti-D) therapy <strong>in</strong>Rh-positive nonanemic children. 1 Each of these approaches<strong>in</strong>terferes with antibody-mediated clearance of platelets,<strong>and</strong> most patients will respond to any of these treatmentswith<strong>in</strong> days of adm<strong>in</strong>istration. Although the <strong>in</strong>fusiontherapies (W<strong>in</strong>Rho or IVIg) are more expensive, these aregenerally the preferred <strong>in</strong>itial approach because of toxicityof glucocorticoids <strong>and</strong> theoretical concerns over partiallytreat<strong>in</strong>g unrecognized acute lymphoblastic leukemia. 25Response to W<strong>in</strong>Rho or IVIg can also help confirm thediagnosis of <strong>ITP</strong>. Antibody-based approaches such as IVIgor W<strong>in</strong>Rho have a typical therapeutic w<strong>in</strong>dow of roughly 3weeks, co<strong>in</strong>cid<strong>in</strong>g with the normal half-life of IgG. Theneed for additional doses of IVIg or W<strong>in</strong>Rho will be dictatedby platelet count <strong>and</strong> how well the patient toleratedprior treatments. It should be noted that <strong>in</strong> 2010, the Food<strong>and</strong> Drug Adm<strong>in</strong>istration issued a black box warn<strong>in</strong>gregard<strong>in</strong>g W<strong>in</strong>Rho <strong>and</strong> the potential for significant <strong>in</strong>travascularhemolysis <strong>and</strong> resultant severe anemia <strong>and</strong> multisystemorgan failure. Risk seems highest <strong>in</strong> patients withpreexist<strong>in</strong>g hemolysis (eg, Evans syndrome), thereforescreen<strong>in</strong>g with Coombs test<strong>in</strong>g or reticulocyte count beforeW<strong>in</strong>Rho adm<strong>in</strong>istration seems reasonable. However, manychildren have been successfully treated with W<strong>in</strong>Rho <strong>and</strong>severe hemolysis is a very rare adverse event. 54 <strong>Current</strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es for W<strong>in</strong>Rho adm<strong>in</strong>istration call for close monitor<strong>in</strong>gof patients for at least 8 hours after <strong>in</strong>fusion, withdipstick ur<strong>in</strong>alysis checks for hematuria <strong>and</strong> hemoglob<strong>in</strong>uria.Glucocorticoids, the third recommended front-l<strong>in</strong>etherapy have long been used for <strong>ITP</strong>, 55 <strong>and</strong> platelet countsusually respond well to oral or <strong>in</strong>travenous steroids. Typically,steroids are prescribed at higher doses <strong>in</strong>itially <strong>and</strong>then weaned as tolerated. Length of steroid therapy istypically for 1 to 2 weeks, but duration is often determ<strong>in</strong>edby platelet response. If steroids must be used chronically,then efforts should be made to f<strong>in</strong>d the lowest therapeuticdose to m<strong>in</strong>imize toxicity.Similar to acute <strong>ITP</strong>, children with chronic <strong>ITP</strong> may notrequire therapy <strong>in</strong> the absence of bleed<strong>in</strong>g symptoms. However,<strong>in</strong> practice, be<strong>in</strong>g able to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a child’s plateletcount >40,000 to 50,000/mL allows significant liberalizationof the patient’s activities. It is estimated that

D’Orazio et al J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 2013TABLE 4. Management Options for Immune Thrombocytopenia<strong>Treatment</strong> Dose Mechanism of Action Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Response ToxicitiesFront-l<strong>in</strong>e therapiesObservation onlywiththrombocytopenicprecautionsIntravenousimmunoglobul<strong>in</strong>(IVIg)W<strong>in</strong>Rho (anti-D)(only for use <strong>in</strong>Rh + patients)GlucocorticoidsSecond-l<strong>in</strong>e approachesObservation onlywiththrombocytopenicprecautionsRituximab (anti-CD20)N/A N/A Symptoms <strong>and</strong> plateletcounts can beexpected to resolvespontaneously <strong>in</strong> mostchildren with<strong>in</strong> weeksto months0.8-1 g/kg, IV over 4-6 h,may repeat dose if noresponse, considerpremedication withdiphenhydram<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong>acetam<strong>in</strong>ophen250 U/kg (50-75 mg/kg),IV over 30 m<strong>in</strong> (withpost<strong>in</strong>fusionmonitor<strong>in</strong>g (8 h) forhemolysis)Pred<strong>in</strong>isone 1-2 mg/kg/ddivided <strong>in</strong>to biddos<strong>in</strong>g for at least1-2 wk, followed byslow taper<strong>in</strong>g weanHigh-dosedexamethasone pulses(20 mg/m 2 /d <strong>in</strong>children or 40 mg/d <strong>in</strong>adults for 4 sequentialdays every 28 dtypically through 6cycles total) may beused for chronic orrefractory immunethrombocytopenia(<strong>ITP</strong>)Antibody excess <strong>and</strong> F creceptor competitionF c receptordownregulation onreticuolendothelialcellsInduction of subcl<strong>in</strong>icalimmune-mediatedhemolytic anemia <strong>and</strong>F c receptorcompetitionF c receptordownregulation onreticuolendothelialcellsImmunosuppressive;<strong>in</strong>terference withantibody productionimpairment ofantibody-coatedplatelet clearance bymacrophagesimpairment of splenicfunctionPlatelet count typicallybeg<strong>in</strong>s to rise <strong>in</strong> aslittle as 24 hPeak responses with<strong>in</strong> aweekEffect typically lastsroughly 3 wkPlatelet count typicallyrich <strong>in</strong> 24-48 hPeak responses with<strong>in</strong> aweekEffect typically lastsroughly 3 wkMany cl<strong>in</strong>icians preferto perform a bonemarrow aspiratebefore start of steroidtherapy due tosteroids efficacy <strong>in</strong>suppress<strong>in</strong>g leukemiccells, <strong>and</strong> potentiallymask<strong>in</strong>g a leukemiapresent<strong>in</strong>g with anisolatedthrombocytopeniaN/A N/A Once <strong>ITP</strong> has persistedfor 6-12 mo, it is likelyto cont<strong>in</strong>ue for sometimeWeekly <strong>in</strong>fusionaltherapy (375 mg/m 2 )for 4 consecutiveweeksChimeric monoclonalantibody that targetsmature B cells thatmanufactureimmunoglobul<strong>in</strong>Goal is to eradicate theplasma cell clonemak<strong>in</strong>g antiplateletantibody.Variable responsivenessOften a very delayedeffect (weeks tomonths)Persistence of symptoms(petechiae, purpurae,mucocutaneousbleed<strong>in</strong>g)Headaches, abdom<strong>in</strong>alpa<strong>in</strong> not <strong>in</strong>frequent(lead<strong>in</strong>g to radiologicimag<strong>in</strong>g)FeverNausea/vomit<strong>in</strong>gInfusion-related chillsHypersensitivityAnaphylaxis(particularly <strong>in</strong> IgAdeficientpatients)Theoretical risk of<strong>in</strong>fectious exposure(pooled plasmaproduct)HeadachesFever, chills,Nausea/vomit<strong>in</strong>gmyalgiaRisk of <strong>in</strong>travascularhemolysis, renalfailure, multiorganfailureDo not use <strong>in</strong> patientswith concurrentautoimmune hemolyticanemia, Evanssyndrome or anemiaHypertensionMood disturbancesHyperphagiaWeight ga<strong>in</strong>, Cush<strong>in</strong>goidhabitusInsul<strong>in</strong> resistance,hyperglycemiaOsteoporosisCataractsCutaneous striaeProlonged activityrestrictionPersistence of symptoms(petechiae, purpurae,mucocutaneousbleed<strong>in</strong>g)HypersensitivityreactionsInfusion reactionsHepatitis B reactivationProgressive multifocalleukoencephalopathyPulmonary toxicity8 | www.jpho-onl<strong>in</strong>e.com r 2012 Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s

J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 2013<strong>ITP</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Children</strong>:<strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Current</strong> <strong>Treatment</strong> <strong>Approaches</strong>TABLE 4. (cont<strong>in</strong>ued)<strong>Treatment</strong> Dose Mechanism of Action Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Response ToxicitiesGood second-l<strong>in</strong>etreatment of refractoryor chronic <strong>ITP</strong>Other agentsImmunosuppressiveagents (tacrolimus,sirolimus,cyclospor<strong>in</strong>e)Chemotherapy(cyclophosphamide,mercaptopur<strong>in</strong>e,v<strong>in</strong>crist<strong>in</strong>e, others)Thrombopoeit<strong>in</strong>agonists(eltrombopag,romiplostim)Immunosuppression orstimulation of marrowplatelet productionVariable responsesThrombopoeit<strong>in</strong>agonists be<strong>in</strong>g tested<strong>in</strong> childrenSee <strong>in</strong>dividual agenttoxicitiesSplenectomyComplete removal ofthe spleen, usuallywith antecedentmedical therapy toraise the platelet countpreoperativelyFront-l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> second-l<strong>in</strong>e approaches are described. 1Surgical removal of theorgan responsible forthe majority ofclearance of antibodyboundplatelets <strong>in</strong> <strong>ITP</strong>Usually associated withrapid platelet<strong>in</strong>creasesSplenectomy restoresadequate plateletcounts <strong>in</strong> the majorityof patientsRelapses ofthrombocytopeniapossible aftersplenectomy <strong>in</strong> somepatientsChronic risk of <strong>in</strong>fection(particularlyencapsulated bacteriasuch asPneumococcus,Neisseria, <strong>and</strong>Haemophilus(immunization,prophylacticantibiotics, fevermanagement allcritical)Chronic risk ofthrombosis <strong>and</strong>pulmonary embolismchildren with <strong>ITP</strong> will require regular platelet-enhanc<strong>in</strong>gtherapy 1 year after diagnosis. 56 For those children whose<strong>ITP</strong> endures for many months or is refractory to treatmentTABLE 5. Immune Thrombocytopenia <strong>Treatment</strong> Responses, asDef<strong>in</strong>ed by the International Work<strong>in</strong>g Group 26CompleteresponseResponseNo responseLoss of completeresponseLoss of responseNo bleed<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong>Platelet count Z100,000/mL measured twiceZ7 d apartNo bleed<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong>Platelet count Z30,000/mL <strong>and</strong> Z2-fold<strong>in</strong>crease from basel<strong>in</strong>e measured twice Z7dapartCont<strong>in</strong>ued bleed<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong>/orPlatelet count

D’Orazio et al J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 2013the antibodies that perpetrate <strong>ITP</strong>. Anti-CD20 therapy,which has been used for over a decade, is generally welltoleratedwith few side effects. 59–61 Although rituximabtherapy can cause generalized decreases <strong>in</strong> antibodyproduction, serious <strong>in</strong>fections are rare after rituximabtreatment. 62 For this reason, rituximab has emerged as awidespread therapy for chronic <strong>ITP</strong> either alone or <strong>in</strong>comb<strong>in</strong>ation with other approaches. 63–67 However, rituximabproduces durable treatment responses <strong>in</strong> only somepatients, with response rates rang<strong>in</strong>g from a less than athird of patients to just over three quarters of patients. 67–69One recent large pediatric collaborative study found anassociation between steroid responsiveness <strong>and</strong> rituximabefficacy, with 87.5% of steroid-responsive chronic <strong>ITP</strong>patients hav<strong>in</strong>g good therapeutic responses to rituximab. 70High-dose dexamethasone—typically 40 mg/d <strong>in</strong>adults (20 mg/m 2 <strong>in</strong> children) for 4 sequential days every 28days—has been used with mixed success for chronic orrefractory <strong>ITP</strong>. Although some studies reported good efficacy<strong>and</strong> low toxicity, 71,72 others found mixed responses<strong>and</strong> significant toxicity (such as hypertension with stroke or<strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>-dependent diabetes). 73 More recent studies suggestthat high-dose dexamethasone may be more useful as afront-l<strong>in</strong>e agent for <strong>ITP</strong> rather than second-l<strong>in</strong>e therapy 74,75<strong>and</strong> that it may be worth try<strong>in</strong>g before splenectomy <strong>in</strong>severe symptomatic chronic childhood <strong>ITP</strong>. 76,77Thrombopoeit<strong>in</strong> agonists are a novel class of <strong>ITP</strong>selectivedrugs may decrease the need for immunosuppressiveor cytotoxic therapies. Eltrombopag (an oral smallmolecule agonist) <strong>and</strong> romiplostim (an Fc-peptide fusionprote<strong>in</strong>) both target <strong>and</strong> activate the thrombopoeit<strong>in</strong>receptor on megakaryocytes. Each serves as a positive signalto stimulate marrow production of platelets. 78 OneFrench study of adult <strong>ITP</strong> patients found that romiplostimcaused platelet counts to rise to at least 50,000/mL <strong>in</strong> 74%of patients <strong>and</strong> that long-term responses of at least 2 yearswere observed <strong>in</strong> 65% of patients. 79 In general, thrombopoeit<strong>in</strong>agonists seem to be well tolerated <strong>in</strong> adults, buttheir safety <strong>in</strong> children has not yet been established. Theseagents are now be<strong>in</strong>g studied <strong>in</strong> children with <strong>ITP</strong>. 42,78SURGICAL MANAGEMENT—SPLENECTOMYSplenectomy has been recognized for nearly a centuryas be<strong>in</strong>g effective treatment for <strong>ITP</strong>. 80 As a reticuloendothelialorgan rich with Fc receptor–express<strong>in</strong>gphagocytes, the spleen is the major site where<strong>in</strong> antibodycoated(opsonized) platelets are actively removed from thecirculation. 81 Thus, removal of the spleen leads to prolongedsurvival of opsonized platelets <strong>in</strong> the circulation.The spleen may also house plasma cells that produce antiplateletantibodies, therefore, splenectomy may help elim<strong>in</strong>atethe source of the errant autoantibodies that cause <strong>ITP</strong>.Although safer today because of better surgical (laparoscopicvs. open) <strong>and</strong> medical care, splenectomy is notwithout risk. 82,83 Splenectomized patients have life-longenhanced risk of thrombosis 84 <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fection. 85,86 The spleenseems especially critical to the clearance of encapsulatedorganisms, therefore, asplenic patients are at risk of Haemophilus,Neisseria, <strong>and</strong> Pneumococcus sepsis 87–90 <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>cidence of overwhelm<strong>in</strong>g sepsis postsplenectomy is on theorder of 1% to 2%. 91 Asplenic patients are also at heightenedrisk of certa<strong>in</strong> protozoal <strong>in</strong>fections, especially malaria<strong>and</strong> babesiosis. 92,93 As <strong>in</strong>fectious risk is particularly highamong very young children, 94 many practitioners defersplenectomy until a m<strong>in</strong>imum of 5 years of age. Immunizationaga<strong>in</strong>st Haemophilus <strong>in</strong>fluenza type B, Men<strong>in</strong>gococcus,<strong>and</strong> Pneumococcus is recommended preoperatively,<strong>and</strong> oral prophylactic antibiotic therapy (typically penicill<strong>in</strong>)is recommended postoperatively, as is appropriatesepsis evaluation for fever. 90,95 Splenectomy is def<strong>in</strong>itivetreatment for most children with <strong>ITP</strong>, rais<strong>in</strong>g their plateletcounts to normal or at least to levels that support liberalizationof physical activities. In one pediatric study, splenectomyresulted <strong>in</strong> significant platelet <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> 85% ofpatients with chronic <strong>ITP</strong>. 83 In comparison, 50% to 60% ofadults with chronic <strong>ITP</strong> respond to splenectomy. 96 Nonetheless,some patients will fail to respond, <strong>and</strong> some <strong>in</strong>itialresponders may have recurrence of thrombocytopenia aftersplenectomy. In a retrospective analysis of over 400 patientswith <strong>ITP</strong>, 23% of splenectomy-responsive patients relapsed,<strong>in</strong> most cases (80%) with<strong>in</strong> 2 years of the procedure. 82Some <strong>ITP</strong> relapses have correlated with the presence ofaccessory spleens. 97 Patients <strong>and</strong> their families mustunderst<strong>and</strong> the unpredictable effectiveness <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>herentrisks of splenectomy for <strong>ITP</strong>. The American Society ofHematology suggests that splenectomy should be consideredfor patients with chronic or persistent <strong>ITP</strong> who havesignificant bleed<strong>in</strong>g symptoms, <strong>in</strong>tolerance of medicaltherapy, or the need for improved quality of life. 1MANAGEMENT OF SERIOUS BLEEDINGThe presence of significant hemorrhage <strong>in</strong> the sett<strong>in</strong>gof <strong>ITP</strong> is a true medical emergency <strong>and</strong> life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g orlimb-threaten<strong>in</strong>g bleed<strong>in</strong>g is an <strong>in</strong>dication for <strong>in</strong>terventionsaimed at quickly rais<strong>in</strong>g platelet count <strong>and</strong> achiev<strong>in</strong>ghemostasis. Intracranial hemorrhage, for example, carries amortality rate of nearly 50% <strong>in</strong> <strong>ITP</strong> patients. 12,98 Medicalmanagement of serious bleed<strong>in</strong>g will be dictated by cl<strong>in</strong>icalcircumstances <strong>and</strong> may <strong>in</strong>volve a variety of medical <strong>and</strong>surgical <strong>in</strong>terventions tried alone or <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation. Massiveor successive platelet transfusions, <strong>in</strong>travenous highdosecorticosteroids, IVIg/W<strong>in</strong>Rho, <strong>and</strong> plasmapheresishave all been described. 99–101 Efforts aimed to <strong>in</strong>terferedirectly with splenic function may also be useful. Thus,emergency splenectomies under “cover” of serial platelettransfusion or medical therapies such as high-dose steroidor IVIg treatment have been described. 102,103 There is atleast 1 case report of comb<strong>in</strong>ation immunosuppressivetherapy (cyclophosphamide, v<strong>in</strong>crist<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>and</strong> corticosteroids)<strong>in</strong> conjunction with frequent transfusions of plateletsbe<strong>in</strong>g used for life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g bleed<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a child with<strong>ITP</strong>. 104 Ligat<strong>in</strong>g or emboliz<strong>in</strong>g the splenic artery usuallyleads to profound <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> the circulat<strong>in</strong>g plateletcounts, <strong>and</strong> may be performed before splenectomy to makeresection of the spleen safer. 105 Fortunately, life-threaten<strong>in</strong>gbleed<strong>in</strong>g is exceed<strong>in</strong>gly rare <strong>in</strong> childhood <strong>ITP</strong>.CONCLUSIONS<strong>ITP</strong> is one of the most common hematologic disordersof childhood <strong>and</strong> adolescence. It is an autoimmune processcharacterized by the <strong>in</strong>appropriate production of antibodiesdirected aga<strong>in</strong>st normal platelets <strong>and</strong> megakaryocytes. As aresult of antibody b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g, platelets <strong>and</strong> their precursors aredestroyed, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> dramatic reductions <strong>in</strong> the numbersof circulat<strong>in</strong>g platelets. Cl<strong>in</strong>ically, this manifests as widespreadappearance of cutaneous <strong>and</strong> mucosal petechiae <strong>and</strong>purpurae. A diagnosis of exclusion, most cases of <strong>ITP</strong> canbe identified by a careful history, physical exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong>10 | www.jpho-onl<strong>in</strong>e.com r 2012 Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s

J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 2013<strong>ITP</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Children</strong>:<strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Current</strong> <strong>Treatment</strong> <strong>Approaches</strong>limited blood work. Although classified as a benign process,<strong>ITP</strong> can have a profound on quality of life <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terferewith normal childhood. Our cl<strong>in</strong>ical case demonstrates thecourse of 1 particular patient with <strong>ITP</strong> whose disease <strong>in</strong>itiallyresponded to therapy but then became therapyrefractory<strong>and</strong> chronic. A variety of medical approacheswere tested until 1 comb<strong>in</strong>ation (sirolumus with <strong>in</strong>termittentW<strong>in</strong>Rho adm<strong>in</strong>istration) was found that ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>edthe platelet count at a reasonable level. This case alsodemonstrates the fact that <strong>ITP</strong> can resolve <strong>in</strong> children evenwhen has persisted for a long time. The <strong>ITP</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g groupof the American Society of Hematology suggests that frontl<strong>in</strong>emanagement for children with <strong>ITP</strong> <strong>in</strong>cludes IVIg, ashort course of corticosteroids or W<strong>in</strong>Rho (Anti-D) therapy<strong>in</strong> Rh-positive non-anemic children. Preferred secondl<strong>in</strong>emedical approaches are rituximab or high-dose dexamethasone.Splenectomy is a very effective therapy formost patients, but because of life-long risks of <strong>in</strong>fection <strong>and</strong>thrombosis, should generally be considered only aftermedical <strong>in</strong>terventions have proven <strong>in</strong>adequate.REFERENCES1. Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, et al. The American Societyof Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guidel<strong>in</strong>e forimmune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2011;117:4190–4207.2. Blanchette V, Bolton-Maggs P. Childhood immune thrombocytopenicpurpura: diagnosis <strong>and</strong> management. PediatrCl<strong>in</strong> North Am. 2008;55:393–420.3. Geddis AE, Baldu<strong>in</strong>i CL. Diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenicpurpura <strong>in</strong> children. Curr Op<strong>in</strong> Hematol. 2007;14:520–525.4. Bryant N, Watts R. Thrombocytopenic syndromes masquerad<strong>in</strong>gas childhood immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Cl<strong>in</strong>Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50:225–230.5. Silverman MA. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. eMedic<strong>in</strong>eMedscape Series. 2011. Available at: http://emedic<strong>in</strong>e.medscape.com/article/779545-overview.6. Branehog I, Kutti J, We<strong>in</strong>feld A. Platelet survival <strong>and</strong> plateletproduction <strong>in</strong> idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (<strong>ITP</strong>). BrJ Haematol. 1974;27:127–143.7. McMillan R, Wang L, Tomer A, et al. Suppression of <strong>in</strong> vitromegakaryocyte production by antiplatelet autoantibodiesfrom adult patients with chronic <strong>ITP</strong>. Blood. 2004;103:1364–1369.8. Diggs LW, Hewlett JS. A study of the bone marrow from 36patients with idiopathic hemorrhagic, thrombopenic purpura.Blood. 1948;3:1090–1104.9. Yong M, Schoonen WM, Li L, et al. Epidemiology ofpaediatric immune thrombocytopenia <strong>in</strong> the General PracticeResearch Database. Br J Haematol. 2010. [Epub 2010/04/10]ISSN: 1365-2141 (electronic).10. Terrell DR, Beebe LA, Vesely SK, et al. The <strong>in</strong>cidence ofimmune thrombocytopenic purpura <strong>in</strong> children <strong>and</strong> adults: acritical review of published reports. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:174–180.11. Wilson DB. Acquired Platelet Defects. In: Ork<strong>in</strong> SH, et al, ed.Hematology of Infancy <strong>and</strong> Childhood. Philadelphia, PA:Saunders Elsevier; 2009:1553–1590.12. Kuhne T, Imbach P, Bolton-Maggs PH, et al. Newlydiagnosed idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura <strong>in</strong> childhood:an observational study. Lancet. 2001;358:2122–2125.13. Kamphuis MM, Oepkes D. Fetal <strong>and</strong> neonatal alloimmunethrombocytopenia: prenatal <strong>in</strong>terventions. Prenat Diagn.2011;31:712–719.14. Skogen B, Killie MK, Kjeldsen-Kragh J, et al. Reconsider<strong>in</strong>gfetal <strong>and</strong> neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia with a focus onscreen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> prevention. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3:559–566.15. Salama A. <strong>Current</strong> treatment options for primary immunethrombocytopenia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2011;4:107–118.16. Pels SG. <strong>Current</strong> therapies <strong>in</strong> primary immune thrombocytopenia.Sem<strong>in</strong> Thromb Hemost. 2011;37:621–630.17. McCrae K. Immune thrombocytopenia: no longer ‘idiopathic’.Cleve Cl<strong>in</strong> J Med. 2011;78:358–373.18. De Mattia D, Del Pr<strong>in</strong>cipe D, Del Vecchio GC, et al.Management of chronic childhood immune thrombocytopenicpurpura: AIEOP consensus guidel<strong>in</strong>es. Acta Haematol.2010;123:96–109.19. Blanchette V, Bolton-Maggs P. Childhood immune thrombocytopenicpurpura: diagnosis <strong>and</strong> management. HematolOncol Cl<strong>in</strong> North Am. 2010;24:249–273.20. Imbach P, Kuhne T, Muller D, et al. Childhood <strong>ITP</strong>: 12months follow-up data from the prospective registry I of theIntercont<strong>in</strong>ental Childhood <strong>ITP</strong> Study Group (ICIS). PediatrBlood Cancer. 2006;46:351–356.21. Kuhne T, Buchanan GR, Zimmerman S, et al. A prospectivecomparative study of 2540 <strong>in</strong>fants <strong>and</strong> children with newlydiagnosed idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (<strong>ITP</strong>) fromthe Intercont<strong>in</strong>ental Childhood <strong>ITP</strong> Study Group. J Pediatr.2003;143:605–608.22. Halper<strong>in</strong> DS, Doyle JJ. Is bone marrow exam<strong>in</strong>ation justified<strong>in</strong> idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura? Am J Dis Child.1988;142:508–511.23. Calp<strong>in</strong> C, Dick P, Poon A, et al. Is bone marrow aspirationneeded <strong>in</strong> acute childhood idiopathic thrombocytopenicpurpura to rule out leukemia? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.1998;152:345–347.24. Ahmad Z, Durrani NU, Hazir T. Bone marrow exam<strong>in</strong>ation<strong>in</strong> <strong>ITP</strong> <strong>in</strong> children: is it m<strong>and</strong>atory? J Coll Physicians SurgPak. 2007;17:347–349.25. Naithani R, Kumar R, Mahapatra M, et al. Is it safe to avoidbone marrow exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> suspected itp? Pediatr HematolOncol. 2007;24:205–207.26. Rodeghiero F, et al. St<strong>and</strong>ardization of term<strong>in</strong>ology, def<strong>in</strong>itions<strong>and</strong> outcome criteria <strong>in</strong> immune thrombocytopenicpurpura of adults <strong>and</strong> children: report from an <strong>in</strong>ternationalwork<strong>in</strong>g group. Blood. 2009;113:2386–2393.27. Garnock-Jones KP, Keam SJ. Eltrombopag. Drugs. 2009;69:567–576.28. Fasola G, Fan<strong>in</strong> R, Masotti A, et al. Long term observationof children with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.Haematologica. 1985;70:419–423.29. George JN, Woolf SH, Raskob GE. Idiopathic thrombocytopenicpurpura: a guidel<strong>in</strong>e for diagnosis <strong>and</strong> management ofchildren <strong>and</strong> adults. American Society of Hematology. AnnMed. 1998;30:38–44.30. Nugent DJ. Childhood immune thrombocytopenic purpura.Blood Rev. 2002;16:27–29.31. Zeller B, Rajantie J, Hedlund-Treutiger I, et al. Childhoodidiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura <strong>in</strong> the Nordic countries:epidemiology <strong>and</strong> predictors of chronic disease. ActaPaediatr. 2005;94:178–184.32. Medeiros D, Buchanan GR. Idiopathic thrombocytopenicpurpura: beyond consensus. Curr Op<strong>in</strong> Pediatr. 2000;12:4–9.33. Bansal D, Bhamare TA, Trehan A, et al. Outcome of chronicidiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura <strong>in</strong> children. PediatrBlood Cancer. 2010;54:403–407.34. Harr<strong>in</strong>gton WJ, M<strong>in</strong>nich V, Holl<strong>in</strong>gsworth JW, et al.Demonstration of a thrombocytopenic factor <strong>in</strong> the bloodof patients with thrombocytopenic purpura. J Lab Cl<strong>in</strong> Med.1951;38:1–10.35. Schwartz RS. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura—fromagony to agonist. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2299–2301.36. Tomer A, Koziol J, McMillan R. Autoimmune thrombocytopenia:flow cytometric determ<strong>in</strong>ation of platelet-associatedautoantibodies aga<strong>in</strong>st platelet-specific receptors. J ThrombHaemost. 2005;3:74–78.37. Beardsley DS, Spiegel JE, Jacobs MM, et al. Plateletmembrane glycoprote<strong>in</strong> IIIa conta<strong>in</strong>s target antigens thatb<strong>in</strong>d anti-platelet antibodies <strong>in</strong> immune thrombocytopenias.J Cl<strong>in</strong> Invest. 1984;74:1701–1707.r 2012 Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s www.jpho-onl<strong>in</strong>e.com | 11

D’Orazio et al J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 201338. Curtis BR, McFarl<strong>and</strong> JG, Wu GG, et al. Antibodies <strong>in</strong>sulfonamide-<strong>in</strong>duced immune thrombocytopenia recognizecalcium-dependent epitopes on the glycoprote<strong>in</strong> IIb/IIIacomplex. Blood. 1994;84:176–183.39. Ho WL, Lee CC, Chen CJ, et al. Cl<strong>in</strong>ical features, prognosticfactors, <strong>and</strong> their relationship with antiplatelet antibodies <strong>in</strong>children with immune thrombocytopenia. J Pediatr HematolOncol. 2012;34:6–12.40. Houwerzijl EJ, Blom NR, van der Want JJ, et al. Ultrastructuralstudy shows morphologic features of apoptosis <strong>and</strong>para-apoptosis <strong>in</strong> megakaryocytes from patients with idiopathicthrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2004;103:500–506.41. Emmons RV, Reid DM, Cohen RL, et al. Human thrombopoiet<strong>in</strong>levels are high when thrombocytopenia is due tomegakaryocyte deficiency <strong>and</strong> low when due to <strong>in</strong>creasedplatelet destruction. Blood. 1996;87:4068–4071.42. Klaassen RJ, Mathias SD, Buchanan G, et al. Pilot study ofthe effect of romiplostim on child health-related quality of life(HRQoL) <strong>and</strong> parental burden <strong>in</strong> immune thrombocytopenia(<strong>ITP</strong>). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:395–398.43. Snyder CF, Mathias SD, Cella D, et al. Health-related qualityof life of immune thrombocytopenic purpura patients: resultsfrom a web-based survey. Curr Med Res Op<strong>in</strong>. 2008;24:2767–2776.44. McMillan R, Bussel JB, George JN, et al. Self-reportedhealth-related quality of life <strong>in</strong> adults with chronic immunethrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:150–154.45. Psaila B, Petrovic A, Page LK, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage(ICH) <strong>in</strong> children with immune thrombocytopenia (<strong>ITP</strong>):study of 40 cases. Blood. 2009;114:4777–4783.46. Daneshvar DH, Now<strong>in</strong>ski CJ, McKee AC, et al. Theepidemiology of sport-related concussion. Cl<strong>in</strong> Sports Med.2011;30:1–17.47. L<strong>in</strong>coln AE, Caswell SV, Almquist JL, et al. Trends <strong>in</strong>concussion <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>in</strong> high school sports: a prospective 11-year study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:958–963.48. Marar M, McIlva<strong>in</strong> NM, Fields SK, et al. Epidemiologyof concussions among United States high school athletes<strong>in</strong> 20 sports. Am J Sports Med. 2012, ISSN: 1552-3365(electronic).49. Kuhne T, Berchtold W, Michaels LA, et al. Newly diagnosedimmune thrombocytopenia <strong>in</strong> children <strong>and</strong> adults: a comparativeprospective observational registry of the Intercont<strong>in</strong>entalCooperative Immune Thrombocytopenia StudyGroup. Haematologica. 2011;96:1831–1837.50. Vesely S, Buchanan GR, Cohen A, et al. Self-reporteddiagnostic <strong>and</strong> management strategies <strong>in</strong> childhood idiopathicthrombocytopenic purpura: results of a survey of practic<strong>in</strong>gpediatric hematology/oncology specialists. J Pediatr HematolOncol. 2000;22:55–61.51. Blanchette VS, Hogan VA, McCombie NE, et al. Intensiveplasma exchange therapy <strong>in</strong> ten patients with idiopathicthrombocytopenic purpura. Transfusion. 1984;24:388–394.52. Hoemberg M, Stahl D, Schlenke P, et al. The isotype ofautoantibodies <strong>in</strong>fluences the phagocytosis of antibodycoatedplatelets <strong>in</strong> autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura.Sc<strong>and</strong> J Immunol. 2011;74:489–495.53. Stasi R. <strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> therapeutic options <strong>in</strong>primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Transfus. 2011;9:262–273.54. Despotovic JM, Lambert MP, Herman JH, et al. RhIG forthe treatment of immune thrombocytopenia: consensus <strong>and</strong>controversy. Transfusion. 2011, ISSN: 1537-2995 (electronic).55. Stefan<strong>in</strong>i M, Perez Santiago E, Chatterjea JB, et al. Corticotrop<strong>in</strong><strong>and</strong> cortisone <strong>in</strong> idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.J Am Med Assoc. 1952;149:647–653.56. Breakey VR, Blanchette VS. Childhood immune thrombocytopenia:a chang<strong>in</strong>g therapeutic l<strong>and</strong>scape. Sem<strong>in</strong> ThrombHemost. 2011;37:745–755.57. Bader-Meunier B, Proulle V, Trichet C, et al. Misdiagnosis ofchronic thrombocytopenia <strong>in</strong> childhood. J Pediatr HematolOncol. 2003;25:548–552.58. Bredlau AL, Semple JW, Segel GB. Management of immunethrombocytopenic purpura <strong>in</strong> children: potential role of novelagents. Paediatr Drugs. 2011;13:213–223.59. Patel K, Berman J, Ferber A, et al. Refractory autoimmunethrombocytopenic purpura treatment with rituximab. AmJ Hematol. 2001;67:59–60.60. Saleh MN, Gutheil J, Moore M, et al. A pilot study of theanti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab <strong>in</strong> patients withrefractory immune thrombocytopenia. Sem<strong>in</strong> Oncol. 2000;27(6 suppl 12):99–103.61. Bussel JB. Overview of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura:new approach to refractory patients. Sem<strong>in</strong> Oncol. 2000;27(6suppl 12):91–98.62. Kumar S, Benseler SM, Kirby-Allen M, et al. B-cell depletionfor autoimmune thrombocytopenia <strong>and</strong> autoimmune hemolyticanemia <strong>in</strong> pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus.Pediatrics. 2009;123:e159–e163.63. Cooper N, Evangelista ML, Amadori S, et al. Shouldrituximab be used before or after splenectomy <strong>in</strong> patientswith immune thrombocytopenic purpura? Curr Op<strong>in</strong> Hematol.2007;14:642–646.64. Zhou Z, Yang R. Rituximab treatment for chronic refractoryidiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.2008;65:21–31.65. Heidel F, Lipka DB, von Auer C, et al. Addition of rituximabto st<strong>and</strong>ard therapy improves response rate <strong>and</strong> progressionfreesurvival <strong>in</strong> relapsed or refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenicpurpura <strong>and</strong> autoimmune haemolytic anaemia.Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:228–233.66. Parodi E, Nobili B, Perrotta S, et al. Rituximab (anti-CD20monoclonal antibody) <strong>in</strong> children with chronic refractorysymptomatic immune thrombocytopenic purpura: efficacy<strong>and</strong> safety of treatment. Int J Hematol. 2006;84:48–53.67. Bennett CM, Rogers ZR, K<strong>in</strong>namon DD, et al. Prospectivephase 1/2 study of rituximab <strong>in</strong> childhood <strong>and</strong> adolescentchronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2006;107:2639–2642.68. Parodi E, Rivetti E, Amendola G, et al. Long-term follow-upanalysis after rituximab therapy <strong>in</strong> children with refractorysymptomatic <strong>ITP</strong>: identification of factors predictive of asusta<strong>in</strong>ed response. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:552–558.69. Brah S, Chiche L, Fanciull<strong>in</strong>o R, et al. Efficacy of rituximab<strong>in</strong> immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a retrospective survey.Ann Hematol. 2012;91:279–285.70. Grace RF, Bennett CM, Ritchey AK, et al. Response to steroidspredicts response to rituximab <strong>in</strong> pediatric chronic immunethrombocytopenia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:221–225.71. Andersen JC. Response of resistant idiopathic thrombocytopenicpurpura to pulsed high-dose dexamethasone therapy. NEngl J Med. 1994;330:1560–1564.72. Adams DM, K<strong>in</strong>ney TR, O’Branski-Rupp E, et al. High-doseoral dexamethasone therapy for chronic childhood idiopathicthrombocytopenic purpura. J Pediatr. 1996;128:281–283.73. Caulier MT, Rose C, Roussel MT, et al. Pulsed highdosedexamethasone <strong>in</strong> refractory chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenicpurpura: a report on 10 cases. Br J Haematol.1995;91:477–479.74. Cheng Y, Wong RS, Soo YO, et al. Initial treatment ofimmune thrombocytopenic purpura with high-dose dexamethasone.N Engl J Med. 2003;349:831–836.75. Borst F, Keun<strong>in</strong>g JJ, van Hulsteijn H, et al. High-dosedexamethasone as a first- <strong>and</strong> second-l<strong>in</strong>e treatment ofidiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura <strong>in</strong> adults. Ann Hematol.2004;83:764–768.76. Wali YA, Al Lamki Z, Shah W, et al. Pulsed high-dosedexamethasone therapy <strong>in</strong> children with chronic idiopathicthrombocytopenic purpura. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;19:329–335.77. Hedlund-Treutiger I, Henter JI, El<strong>in</strong>der G. R<strong>and</strong>omizedstudy of IVIg <strong>and</strong> high-dose dexamethasone therapy forchildren with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. JPediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:139–144.12 | www.jpho-onl<strong>in</strong>e.com r 2012 Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s

J Pediatr Hematol Oncol Volume 35, Number 1, January 2013<strong>ITP</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Children</strong>:<strong>Pathophysiology</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Current</strong> <strong>Treatment</strong> <strong>Approaches</strong>78. Bussel JB, P<strong>in</strong>heiro MP. Eltrombopag. Cancer Treat Res.2011;157:289–303.79. Khellaf M, Michel M, Quittet P, et al. Romiplostim safety<strong>and</strong> efficacy for immune thrombocytopenia <strong>in</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical practice:2-year results of 72 adults <strong>in</strong> a romiplostim compassionate-useprogram. Blood. 2011;118:4338–4345.80. Kaznelson P. Disappearance of hemorrhagic diathesis of“essential thrombocytopenia” after splenectomy: splenogenicthrombolytic purpura. Wien Kl<strong>in</strong> Wochenschr. 1916;29:1451–1454. [German].81. S<strong>and</strong>ler SG. The spleen <strong>and</strong> splenectomy <strong>in</strong> immune(idiopathic) thrombocytopenic purpura. Sem<strong>in</strong> Hematol.2000;37(1 suppl 1):10–12.82. Vianelli N, Galli M, de Vivo A, et al. Efficacy <strong>and</strong> safety ofsplenectomy <strong>in</strong> immune thrombocytopenic purpura: longtermresults of 402 cases. Haematologica. 2005;90:72–77.83. Aronis S, Platokouki H, Avgeri M, et al. Retrospectiveevaluation of long-term efficacy <strong>and</strong> safety of splenectomy <strong>in</strong>chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura <strong>in</strong> children.Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:638–642.84. Mohren M, Markmann I, Dworschak U, et al. Thromboemboliccomplications after splenectomy for hematologic diseases.Am J Hematol. 2004;76:143–147.85. Zarrabi MH, Rosner F. Serious <strong>in</strong>fections <strong>in</strong> adults follow<strong>in</strong>gsplenectomy for trauma. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1421–1424.86. Rodeghiero F, Frezzato M, Schiavotto C, et al. Fulm<strong>in</strong>antsepsis <strong>in</strong> adults splenectomized for idiopathic thrombocytopenicpurpura. Haematologica. 1992;77:253–256.87. Ramsay LE. Letter: <strong>in</strong>fections <strong>in</strong> asplenic adults. Br Med J.1974;3:254–255.88. Hosea SW. Role of the spleen <strong>in</strong> pneumococcal <strong>in</strong>fection.Lymphology. 1983;16:115–120.89. Malangoni MA, Dillon LD, Klamer TW, et al. Factors<strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g the risk of early <strong>and</strong> late serious <strong>in</strong>fection <strong>in</strong> adultsafter splenectomy for trauma. Surgery. 1984;96:775–783.90. Castagnola E, Fioredda F. Prevention of life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>fectionsdue to encapsulated bacteria <strong>in</strong> children with hypospleniaor asplenia: a brief review of current recommendations forpractical purposes. Eur J Haematol. 2003;71:319–326.91. Kessler C, S<strong>and</strong>ler SG, Bhanji R. Immune thrombocytopeniapurpura. eMedic<strong>in</strong>e Medscape Series. 2012, Available at:http://emedic<strong>in</strong>e.medscape.com/article/202158-overview.92. Chotivanich K, Udomsangpetch R, McGready R, et al.Central role of the spleen <strong>in</strong> malaria parasite clearance.J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1538–1541.93. Slovut DP, Benedetti E, Matas AJ. Babesiosis <strong>and</strong> hemophagocyticsyndrome <strong>in</strong> an asplenic renal transplant recipient.Transplantation. 1996;62:537–539.94. E<strong>in</strong> SH, Sh<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>g B, Simpson JS, et al. The morbidity <strong>and</strong>mortality of splenectomy <strong>in</strong> childhood. Ann Surg. 1977;185:307–310.95. Jones P, Leder K, Woolley I, et al. Postsplenectomy<strong>in</strong>fection—strategies for prevention <strong>in</strong> general practice. AustFam Physician. 2010;39:383–386.96. Bell WR Jr. Long-term outcome of splenectomy for idiopathicthrombocytopenic purpura. Sem<strong>in</strong> Hematol. 2000;37(1 suppl 1):22–25.97. Rudowski WJ. Accessory spleens: cl<strong>in</strong>ical significance withparticular reference to the recurrence of idiopathic thrombocytopenicpurpura. World J Surg. 1985;9:422–430.98. Woerner SJ, Abildgaard CF, French BN. Intracranialhemorrhage <strong>in</strong> children with idiopathic thrombocytopenicpurpura. Pediatrics. 1981;67:453–460.99. Hoots WK, Hunt<strong>in</strong>gton D, Dev<strong>in</strong>e D, et al. Aggressivecomb<strong>in</strong>ation therapy <strong>in</strong> the successful management of lifethreaten<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>tracranial hemorrhage <strong>in</strong> a patient withidiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Pediatr HematolOncol. 1986;8:225–230.100. Spahr JE, Rodgers GM. <strong>Treatment</strong> of immune-mediatedthrombocytopenia purpura with concurrent <strong>in</strong>travenousimmunoglobul<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> platelet transfusion: a retrospectivereview of 40 patients. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:122–125.101. Salama A, Kiesewetter H, Kalus U, et al. Massive platelettransfusion is a rapidly effective emergency treatment <strong>in</strong>patients with refractory autoimmune thrombocytopenia.Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:762–765.102. Wanachiwanaw<strong>in</strong> W, Piankijagum A, S<strong>in</strong>dhvan<strong>and</strong>a K, et al.Emergency splenectomy <strong>in</strong> adult idiopathic thrombocytopenicpurpura. A report of seven cases. Arch Intern Med.1989;149:217–219.103. Zerella JT, Mart<strong>in</strong> LW, Lampk<strong>in</strong> BC. Emergency splenectomyfor idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura <strong>in</strong> children.J Pediatr Surg. 1978;13:243–246.104. Lightsey AL Jr, McMillan R, Koenig HM. Childhoodidiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Aggressive managementof life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g complications. JAMA. 1975;232:734–736.105. Puapong D, Terasaki K, Lacerna M, et al. Splenic arteryembolization <strong>in</strong> the management of an acute immunethrombocytopenic purpura-related <strong>in</strong>tracranial hemorrhage.J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:869–871.r 2012 Lipp<strong>in</strong>cott Williams & Wilk<strong>in</strong>s www.jpho-onl<strong>in</strong>e.com | 13