18 Children in Western pennsylvania and around the ... - Pitt Med

18 Children in Western pennsylvania and around the ... - Pitt Med

18 Children in Western pennsylvania and around the ... - Pitt Med

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

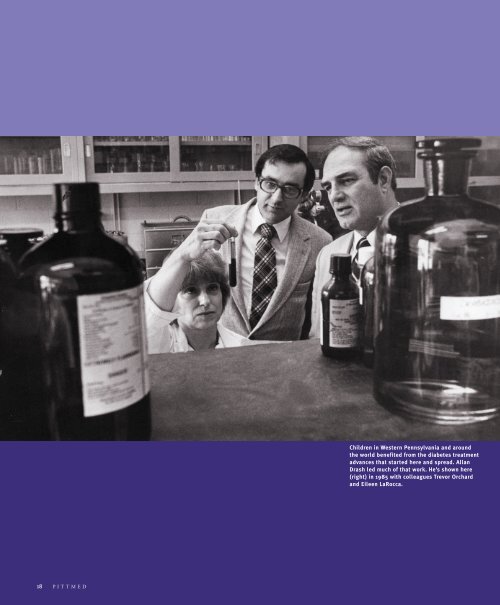

<strong>18</strong> P I T T M E D<strong>Children</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Western</strong> Pennsylvania <strong>and</strong> <strong>around</strong><strong>the</strong> world benefited from <strong>the</strong> diabetes treatmentadvances that started here <strong>and</strong> spread. AllanDrash led much of that work. He’s shown here(right) <strong>in</strong> 1985 with colleagues Trevor Orchard<strong>and</strong> Eileen LaRocca.

f e a t u r et h e d o c w h o b u i l t a d i a b e t e st r e a t m e n t a n d r e s e a r c h c e n t e rw i t h o u t p e e r | b y C h u c k S t a r e s i n i c“We HadDr. Drash”© <strong>Pitt</strong>sburg h Post-Gazette, All rig hts r e se rved. R e pri nted with pe rm ission. Photo by Harry Coug hanou r 1985.Aslight 6-year-old girl from <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh’s North Side becameill with a virus one day. Her sickness was not all thatunusual—she developed a fever <strong>and</strong> was vomit<strong>in</strong>g. Butwhen she failed to bounce back after several days, her parents took herto <strong>the</strong> pediatrician, who said, “She has a virus,” <strong>and</strong> sent her home with<strong>in</strong>structions to rest <strong>and</strong> wait it out.This was <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early 1970s. She may have had a run-of-<strong>the</strong>-millviral <strong>in</strong>fection <strong>in</strong>itially, but someth<strong>in</strong>g else was happen<strong>in</strong>g now. Shelost weight. She ur<strong>in</strong>ated a lot, <strong>and</strong> she was always thirsty. The parentsbypassed <strong>the</strong>ir pediatrician <strong>and</strong> brought her straight to <strong>Children</strong>’sHospital of <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh. It seemed like <strong>the</strong>y had been <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> hospital onlymoments when someone said, “This looks like diabetes.”Those were scary words. Diabetes may be manageable, but much lesswas known about how to manage it back <strong>the</strong>n. All <strong>the</strong> parents knew wasthat <strong>the</strong>ir child was no longer just sick; she had an <strong>in</strong>curable disease. Somechildren entered <strong>the</strong> hospital <strong>in</strong> her state, cont<strong>in</strong>ued to deteriorate, <strong>and</strong>died. Some came home less than whole. They were frail or had damagedm<strong>in</strong>ds. O<strong>the</strong>rs survived but lost someth<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong>ir childhood.At <strong>Children</strong>’s, <strong>the</strong> physicians <strong>and</strong> nurses saw it a bit differently. Therewas an acute crisis to overcome <strong>in</strong> that <strong>the</strong> girl’s blood was becom<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly acidic. This was life-threaten<strong>in</strong>g, but if she overcame it, <strong>the</strong>family could manage her disease.S P R I N G 2 0 1 0 19

Ketoacidosis, as <strong>the</strong> condition is called, is<strong>the</strong> most common, acute, <strong>and</strong> serious complicationresult<strong>in</strong>g from diabetes <strong>in</strong> childhood.The crisis often leads to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial diagnosis.The problem beg<strong>in</strong>s, many experts believe,when <strong>the</strong> immune system reacts to a commonvirus <strong>in</strong> an uncommon way. Ra<strong>the</strong>r thanfight<strong>in</strong>g off <strong>the</strong> virus, <strong>the</strong>n ramp<strong>in</strong>g down<strong>the</strong> attack, <strong>the</strong> immune system cont<strong>in</strong>ues itsassault, attack<strong>in</strong>g cells <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreas.Tucked <strong>in</strong>to pearly clusters <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> pancreascalled islets of Langerhans, <strong>the</strong>se cells produce<strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>, a hormone that metabolizes glucoseto fuel <strong>the</strong> body. When <strong>the</strong> body experiencesa glucose shortage, it beg<strong>in</strong>s to metabolizefat <strong>in</strong>stead, caus<strong>in</strong>g sudden weight loss <strong>and</strong>a buildup of acidic byproducts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bloodcalled ketones. Uncontrolled, it can lead toswell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bra<strong>in</strong>, kidney failure, death ofbowel tissue, <strong>and</strong> heart attack.Through happenstance, <strong>the</strong> girl’s familyhad arrived at what was arguably <strong>the</strong> best place<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world for a diabetic child to go. Whatis now <strong>Children</strong>’s Hospital of <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh ofUPMC <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> University of <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh werebuild<strong>in</strong>g a diabetes research center withoutpeer. <strong>Children</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Western</strong> Pennsylvania benefitedfrom <strong>the</strong> treatment advances that startedhere <strong>and</strong> spread <strong>around</strong> <strong>the</strong> world.The physician who walked <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> roomthat day <strong>and</strong> talked with <strong>the</strong> family about<strong>the</strong>ir daughter’s diagnosis was <strong>the</strong> one mostresponsible for <strong>the</strong> bustl<strong>in</strong>g hive of diabetesrelatedresearch <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh: Allan Drash,a pediatric endocr<strong>in</strong>ologist <strong>and</strong> professor ofpediatrics <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> University of <strong>Pitt</strong>sburghSchool of <strong>Med</strong>ic<strong>in</strong>e. He <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs had createda multifaceted center that simultaneouslyadvanced <strong>the</strong> treatment of diabetic patients<strong>and</strong> probed <strong>the</strong> underly<strong>in</strong>g epidemiology—who gets <strong>the</strong> disease, <strong>and</strong> why?The girl <strong>in</strong> our story not only recoveredfrom her bout with ketoacidosis, but she alsowent on to become a nurse <strong>and</strong> a diabeteseducator. For decades afterward, she <strong>and</strong> herparents remembered <strong>the</strong> words of Dr. Drash.He told <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> disease could be managed.“Diabetes will become a part of yourlife,” he said, “but do not give up on yourdreams for your child. She can achieve anyth<strong>in</strong>gshe puts her m<strong>in</strong>d to.”Allan Drash was a Tennessee nativewho stayed close to home for college(V<strong>and</strong>erbilt University), <strong>the</strong>n went tomedical school at <strong>the</strong> University of Virg<strong>in</strong>ia,tra<strong>in</strong>ed at Johns Hopk<strong>in</strong>s Hospital, <strong>and</strong> lateraccepted a position with <strong>Children</strong>’s Hospitalof <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh. He was a pediatric endocr<strong>in</strong>ologistwho set about perfect<strong>in</strong>g a cl<strong>in</strong>ic totreat children suffer<strong>in</strong>g from diabetes.The year was 1966, <strong>and</strong>, compared to whatwe know now, physicians had an <strong>in</strong>completeunderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> disease. They knew thatmany people experienced adult-onset diabetes<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir 40s or later. These people showed<strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong> resistance, mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong> didn’tprocess glucose as well as it should have. O<strong>the</strong>rpeople developed diabetes <strong>in</strong> childhood orearly adulthood. Both of <strong>the</strong>se groups experiencedhyperglycemia—excess sugar <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>blood. But it wasn’t clear whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>re weremajor differences between <strong>the</strong> two types ofdiabetes aside from <strong>the</strong> age of onset.“Diabetes will become part of your life,” he said,“but do not give up on your dreams for your child.”In 1967, one year after arriv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh, Drash published a study confirm<strong>in</strong>gthat most children with diabetes were not<strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong> resistant like most adults with diabetes.The children were <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong> deficient. They hadno <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>, or <strong>the</strong>y had not nearly enough.The study contributed to a new underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gthat <strong>the</strong>re were two types of diabetes: Type1 usually came to light <strong>in</strong> childhood <strong>and</strong> wasmarked by a deficiency of <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>. Type 2 usuallyappeared <strong>in</strong> adulthood <strong>and</strong> was marked by<strong>the</strong> body’s resistance to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong> it produced.Drash’s motivation was to f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> besttreatment for diabetic children. Aggressivetreatment with <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>jections eventuallybecame <strong>the</strong> unquestioned st<strong>and</strong>ard of care fortype 1—hence <strong>the</strong> moniker <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>-dependentdiabetes. Drash was <strong>in</strong>strumental <strong>in</strong> push<strong>in</strong>gfor federal fund<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> Diabetes Control<strong>and</strong> Complication Trial, which eventuallygrew to 29 sites. It demonstrated that metaboliccontrol was critically important <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>development <strong>and</strong> rate of progression of vascularcomplications <strong>in</strong> people with diabetes.And it showed that an aggressive regimen that<strong>in</strong>cluded multiple daily <strong>in</strong>jections of <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>was <strong>the</strong> most important element of treatment.He quietly fomented a revolution <strong>in</strong> endocr<strong>in</strong>ologyat a time when pediatric endocr<strong>in</strong>ologywas a ra<strong>the</strong>r neglected field. Atprofessional conferences, he <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r endocr<strong>in</strong>ologistswho treated children typically hada session or two devoted to <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>terests. Hiswork on diabetes illustrated his po<strong>in</strong>t thatchildren were not just smaller <strong>in</strong> size thanadult patients: Diabetes, like many o<strong>the</strong>rendocr<strong>in</strong>e disorders, was fundamentally different<strong>in</strong> children than it was <strong>in</strong> adults. Drashlobbied for pediatric endocr<strong>in</strong>ology to betaken more seriously. And, over <strong>the</strong> course ofhis career, it was.In <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh, Drash employed a uniqueteam approach to treat<strong>in</strong>g diabetes. Hebelieved <strong>in</strong> treat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> family, not just<strong>the</strong> child. He enlisted nutritionists, nurses,social workers, educators, <strong>and</strong> psychologists.Physicians <strong>in</strong> his cl<strong>in</strong>ic were just one part ofa team that strived to educate <strong>the</strong> family <strong>and</strong>manage <strong>the</strong> disease with aggressive monitor<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervention.With philanthropic help, <strong>Children</strong>’sHospital provided fund<strong>in</strong>g so that familieswho could not o<strong>the</strong>rwise afford care couldreceive <strong>the</strong> same treatment.The epidemiology of diabetes <strong>in</strong>triguedDrash. There were h<strong>in</strong>ts that genetics playeda role—sibl<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r relatives of diabeticchildren seemed to be at higher risk of develop<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> disease. Because early diagnosis <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>tervention were important elements of successfultreatment, Drash believed that epidemiologywas a natural extension of <strong>the</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ic.In <strong>the</strong> early 1970s, Drash <strong>and</strong> epidemiologistLewis Kuller developed a registry that aimedto <strong>in</strong>clude every child <strong>in</strong> Allegheny Countydiagnosed with type 1 diabetes.“Allan focused very much on develop<strong>in</strong>gan unusual, multidiscipl<strong>in</strong>ary cl<strong>in</strong>ic that gavequality care for children,” says Kuller, whois now a Dist<strong>in</strong>guished Professor of PublicHealth at <strong>Pitt</strong>. “And that helped <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> registry <strong>and</strong> gett<strong>in</strong>g families <strong>and</strong>patients <strong>in</strong>to research programs. The researchprogram just blossomed dramatically.”Epidemiologists who tra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh<strong>in</strong>clude Ronald LaPorte, a <strong>Pitt</strong> professor ofepidemiology who led <strong>the</strong> diabetes projectfor years, <strong>and</strong> Trevor Orchard, currently <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>terim chair of epidemiology at <strong>Pitt</strong>.The diabetes epidemiology group <strong>in</strong><strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh exported <strong>the</strong> model worldwide,with Drash as its pr<strong>in</strong>cipal ambassador. In1990, Drash calculated that he had averaged100 days of travel per year for <strong>the</strong> preced<strong>in</strong>geight years. “We were married 38 years,” saysDiane Drash. “There were no real holidays.20 P I T T M E D

We would travel for meet<strong>in</strong>gs, or when hewould lecture or give a keynote address at aconference.”She recalls her husb<strong>and</strong>, who died onAugust 3, 2009, visit<strong>in</strong>g cl<strong>in</strong>ics <strong>around</strong> <strong>the</strong>world: “I loved to watch him <strong>in</strong>teract withparents <strong>and</strong> children. His whole life was built<strong>around</strong> try<strong>in</strong>g to help children with diabetes<strong>and</strong> to reassure parents.”His travel <strong>and</strong> years of professional dutiesled to one memorable argument with his<strong>the</strong>n-teenage daughter, one of two Drashchildren. A few days later, Drash wrote a long,thoughtful letter to his daughter about hisreasons for be<strong>in</strong>g dedicated to his profession<strong>and</strong> his love for her.He wrote, “There is noth<strong>in</strong>g more importantthan to be consumed by a sense ofdedication <strong>and</strong> responsibility to a profession,a call<strong>in</strong>g, that takes one out of one’s own self<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> service of o<strong>the</strong>rs. It is not <strong>the</strong> jobof medic<strong>in</strong>e that is dem<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g, but that weare dem<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of ourselves.”About his dreams for her, he wrote,“Despite what <strong>the</strong> U.S. Constitution says…Happ<strong>in</strong>ess should not be pursued. It is <strong>the</strong>byproduct of a mean<strong>in</strong>gful, contribut<strong>in</strong>g life.I hope for you such a life.”At <strong>Children</strong>’s Hospital of <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh,Drash tra<strong>in</strong>ed a long l<strong>in</strong>e of stellarpediatric endocr<strong>in</strong>ologists. DorothyBecker is a <strong>Pitt</strong> professor of pediatrics whonow occupies Drash’s former position as chiefof pediatric endocr<strong>in</strong>ology <strong>and</strong> diabetes. Shealso is <strong>the</strong> director of <strong>the</strong> diabetes programat <strong>Children</strong>’s <strong>and</strong> is pr<strong>in</strong>cipal <strong>in</strong>vestigatoron a multicenter trial funded by <strong>the</strong> NIH todeterm<strong>in</strong>e whe<strong>the</strong>r a cow’s-milk <strong>in</strong>fant formulacan keep children from later develop<strong>in</strong>gtype 2 diabetes. She “cont<strong>in</strong>ues to carry forward[Drash’s] <strong>in</strong>vestigative prowess,” notesOrchard. Ingrid Libman is ano<strong>the</strong>r Drashtra<strong>in</strong>ee, an MD/PhD assistant professor ofpediatrics who works <strong>in</strong> prevention <strong>and</strong> treatmentof type 2 diabetes <strong>in</strong> children. SilvaArslanian, <strong>the</strong> Richard L. Day Professor ofPediatrics, is an <strong>in</strong>ternationally recognizedendocr<strong>in</strong>ologist <strong>and</strong> authority on <strong>the</strong> longtermconsequences of type 2 diabetes <strong>and</strong>racial disparities <strong>in</strong> its prevalence.<strong>Pitt</strong>’s diabetes epidemiology project wasprobably <strong>the</strong> largest such project <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> world,Kuller says. “In our <strong>in</strong>ternational project, wehad 155 centers <strong>in</strong> 70 countries across <strong>the</strong>world. For a while, we were publish<strong>in</strong>g 35to 40 papers a year at a time when we wereprobably responsible for 20 to 30 percent of<strong>the</strong> world’s literature <strong>in</strong> that area.” To offerevidence, Kuller walks to a bookshelf across<strong>the</strong> hall from his office. He pulls down a fewbound sets of scientific papers, each roughly asthick as <strong>the</strong> <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh telephone book.“This is [from] <strong>the</strong> early days,” he says,pag<strong>in</strong>g through <strong>the</strong> bibliography <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> frontof one volume. “It’s almost all Drash. It’sDrash <strong>and</strong> epidemiology group. It was a broadproject, from <strong>the</strong> basic immunology all <strong>the</strong>way up to <strong>the</strong> global work.”<strong>Pitt</strong>’s reputation has attracted expertisethroughout <strong>the</strong> health sciences schools.L<strong>in</strong>da Sim<strong>in</strong>erio—a diabetes educator, facultymember <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> schools of medic<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong>nurs<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> executive director of <strong>the</strong>University of <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh Diabetes Institute—was <strong>the</strong> national spokesperson for WorldDiabetes Day <strong>in</strong> 2009.Andrew Stewart, <strong>Pitt</strong> professor of medic<strong>in</strong>e<strong>and</strong> chief of <strong>the</strong> Division of Endocr<strong>in</strong>ology<strong>and</strong> Metabolism, left Yale University to jo<strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>Pitt</strong> faculty <strong>in</strong> 1997. Stewart’s lab hasidentified <strong>the</strong> genes <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> creation of new <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>-produc<strong>in</strong>g cells.Stewart is explor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> possibility that wemight stimulate <strong>the</strong> production of new cells <strong>in</strong>patients with diabetes, restor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir abilityto manufacture <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>.In <strong>the</strong> mid-’80s, Drash <strong>and</strong> his colleaguesrecruited Massimo Trucco, an MD immunologist<strong>and</strong> geneticist who was prepared to take<strong>the</strong> expertise <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh <strong>and</strong> build on it tocreate a new underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> basic immunology<strong>and</strong> genetics beh<strong>in</strong>d type 1 diabetes.Today, <strong>Pitt</strong>’s Trucco is <strong>the</strong> Hillman Professor ofPediatric Immunology, a professor of pathology,human genetics, <strong>and</strong> epidemiology, as wellas director of <strong>the</strong> Division of Immunogenetics.Simply put, Trucco is on <strong>the</strong> trail of a curefor diabetes. He has uncovered genes thatconfer susceptibility to type 1 diabetes <strong>and</strong>described some of <strong>the</strong> molecular activities <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> immune system that cause <strong>the</strong> destructionof <strong>in</strong>sul<strong>in</strong>-produc<strong>in</strong>g cells. Trucco <strong>and</strong> hiscolleagues—notably Nick Giannoukakis, anassociate professor of pathology <strong>and</strong> immunology—havedeveloped cell <strong>and</strong> microparticlevacc<strong>in</strong>es that reverse or prevent type 1diabetes <strong>in</strong> mice. The group is wrapp<strong>in</strong>g up asafety trial of a vacc<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> recently diagnosedchildren.‘‘D I A B E T E S I N V E S T M E N T SAllan had this phenomenal commitmentto tak<strong>in</strong>g care of <strong>the</strong> people,”says Kuller. “It wasn’t just screen<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong>se kids to do an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g genetic study.He was actually say<strong>in</strong>g, ‘Hey, what are wego<strong>in</strong>g to do about it?’”For much of four decades, until his deathlast year, Drash was <strong>the</strong> doctor lead<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> wayfor families <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh with diabetic children.One former patient says it’s impossibleto overstate <strong>the</strong> significance of his words <strong>and</strong>actions on her family. Drash told her parentsnot to let <strong>the</strong>ir child be def<strong>in</strong>ed by a diagnosis:“We all know what that diagnosis means.It’s this overwhelm<strong>in</strong>g shadow of darkness.But we never had that. We had Dr. Drash.” n<strong>Children</strong>’s Hospital is establish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> AllanDrash Diabetes Scholarship to fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>careers of pediatric diabetes tra<strong>in</strong>ees <strong>and</strong>perpetuate Dr. Drash’s work. To contributecontact Chip Eagle, 412-586-6317chip.eagle@chp.eduTo protect patient privacy, some details werechanged <strong>in</strong> this story.When he was 35 years old, Allan Drash received an offer to relocate fromJohns Hopk<strong>in</strong>s University to <strong>Children</strong>’s Hospital of <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>University of <strong>Pitt</strong>sburgh. One of <strong>the</strong> attractions for Drash was that, at<strong>Children</strong>’s, <strong>the</strong> diabetes cl<strong>in</strong>ic had long been a priority. A $1 million fundhad been established <strong>in</strong> 1937 by Emilie Renziehausen to support <strong>the</strong> care ofdiabetic children <strong>and</strong> honor <strong>the</strong> memory of her two bro<strong>the</strong>rs, one of whomhad diabetes. The <strong>in</strong>terest from that fund has contributed to cl<strong>in</strong>ical care at<strong>Children</strong>’s for more than 70 years. The fund allows for aggressive outreach tofamilies cop<strong>in</strong>g with diabetes, regardless of <strong>the</strong> family’s f<strong>in</strong>ancial situation.Additional gifts from <strong>the</strong> Renziehausen family through <strong>the</strong> years have createdan additional trust fund at <strong>Children</strong>’s to support laboratory research <strong>and</strong> education.These deep roots have nourished an extraord<strong>in</strong>ary breadth <strong>and</strong> depthof diabetes research at <strong>Pitt</strong>. —CSS P R I N G 2 0 1 0 21

![entire issue [pdf 2.79 mb] - Pitt Med - University of Pittsburgh](https://img.yumpu.com/50435398/1/190x231/entire-issue-pdf-279-mb-pitt-med-university-of-pittsburgh.jpg?quality=85)

![entire issue [pdf 6.47 mb] - Pitt Med - University of Pittsburgh](https://img.yumpu.com/50360689/1/190x231/entire-issue-pdf-647-mb-pitt-med-university-of-pittsburgh.jpg?quality=85)

![entire issue [pdf 12.7 mb] - Pitt Med - University of Pittsburgh](https://img.yumpu.com/49831615/1/190x231/entire-issue-pdf-127-mb-pitt-med-university-of-pittsburgh.jpg?quality=85)

![entire issue [pdf 11.3 mb] - Pitt Med - University of Pittsburgh](https://img.yumpu.com/46685830/1/190x231/entire-issue-pdf-113-mb-pitt-med-university-of-pittsburgh.jpg?quality=85)

![entire issue [pdf 12.7 mb] - Pitt Med - University of Pittsburgh](https://img.yumpu.com/44997419/1/190x231/entire-issue-pdf-127-mb-pitt-med-university-of-pittsburgh.jpg?quality=85)