Geography of Evolution.pdf

Geography of Evolution.pdf

Geography of Evolution.pdf

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

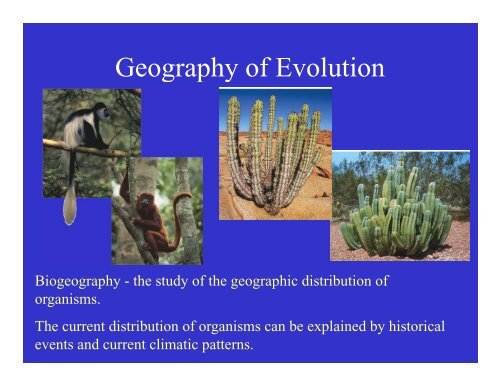

Darwin was the first to draw attention to the distribution <strong>of</strong>organisms and their implications for understandingevolution.• Neither the similarity or dissimilarity <strong>of</strong> the inhabitants<strong>of</strong> various regions can be wholly accounted for by climatalor other physical conditions.• Barriers <strong>of</strong> any kind, or obstacles to free migration, arerelated in a close and important manner to the differencesbetween the productions <strong>of</strong> various regions.• Inhabitants <strong>of</strong> the same continent or the same sea arerelated, although the species themselves differ from placeto place.

Darwin argued that the evidence against special creation wasapparent in biogeography.• Organisms found on oceanic islands are the kinds <strong>of</strong>organisms that have the capacity for long-distance dispersal.• Organisms without dispersal abilities <strong>of</strong>ten do well on islandswhen they are transported there by humans.• Most <strong>of</strong> the species on islands are clearly related to specieson the nearest mainland.• The proportion <strong>of</strong> endemic species on an island is particularlyhigh when the opportunity for dispersal to the island is low.• Island species <strong>of</strong>ten bear marks <strong>of</strong> their continental ancestry.

Biogeographic PatternsThe distribution <strong>of</strong> higher taxa allow the designation <strong>of</strong> several“biogeographic realms. ” The biogeographic realms are defined bygroups <strong>of</strong> organisms that are unique to or highly diverse withinthose regions.

Eachbiogeographicrealm has somespecies orhigher taxa thatare endemic -found nowhereelse.The pattern <strong>of</strong> endemism is repeatedin many groups within abiogeographic realmArmadillos, anteaters, antshrikes,Armadillos, anteaters, antshrikes,and armored catfishes are SouthAmerican endemics.

Biogeographic g realms are largely the product <strong>of</strong> geologic g history- the movement <strong>of</strong> continental landmasses.A single interconnected landmass - “Pangaea” was present inthe Triassic. The climate was warm and many organismswere widely distributed.

During the Jurassic the northern continents were largely separatedDuring the Jurassic the northern continents were largely separated,but a single large southern continent “Gondwana” remained.

At the end <strong>of</strong> the Mesozoic, the southern continents hadseparated. Shallow oceans covered the interior North Americaand Eurasia. Some landmasses were in very different positionsthan today. India was a large island <strong>of</strong>f the east coast <strong>of</strong> Africaand Australia was very close to Antarctica.

By the middle <strong>of</strong> the Tertiary the continents were positioned as weknow them today. India collided with Asia and the Himalayaswere built. Australia was isolated in the southern Indo-Pacific.North and South America were still separated by a seaway throughwhat is now Central America.

Within a biogeographic realm, the flora or fauna may be dividedinto provinces based on restricted distributions <strong>of</strong> species or groups<strong>of</strong> species.

The borders between adjoining realms and provinces are notabsolute because some are relatively recent and thus some taxa areshared between them due to having a once widespread ancestor.For example, some closely related species <strong>of</strong> animals and plantsare shared between Europe and North America. Each is likely tohave a common ancestor that existed on both continents beforetheir separation.North AmericandaceEuropeanSycamorePlanetree

ys[kk Lda/kfon`çfu dk ys[kk Lda/k çR;sd o"kZ ehfM;k laxBuksa] ftuesa lekpkj i=] Vh-oh- pSuy] jsfM;ks pSuy] ckg~; çpkj ,tsafl;ka'kkfey gSa] lfgr laxBu ds iSuy esa 'kkfey fuekZrkvksa rFkk fçafVax gkmlksa dks yxHkx 650 ls 700 djksM :i,+ dsHkqxrku dk fuiVkjk djrk gSA vij egkfuns'kd ¼ys[kk½ dh v/;{krk esa bl Lda/k esa funs'kd ¼ys[kk½] foÙkh; lykgdkjrFkk eq[; ys[kk vf/kdkjh] Ng ys[kk vf/kdkjh] rhu lgk- ys[kk vf/kdkjh rFkk ikap ys[kkdkj@d- ys[kkdkj 'kkfey gSaAfoKkiu ds çlkj.k vFkok çdk'ku dh tkap rFkk fon`çfu }kjk mUgsa fn, x, voekspu vkns'k esa nh xbZ 'krk±s ds vk/kkjij Hkqxrkuksa dk fuiVkjk fd;k tkrk gSAeq[; miyfC/k;ka% ys[kk Lda/k dh eq[; miyfC/k;ka fuEufyf[kr gSa1) vc lHkh futh ikfVZ;ksa dks yxHkx 100 çfr'kr Hkqxrku ;kaf=d fuf/k LFkkukarj.k ¼bySDVªkfud QaM~l VªkalQj½}kjk rRdky fd;k tkus yxk gS ftlls Mkd }kjk pSdksa ds ikjxeu esa nsjh rFkk [kksus dh vk'kadk [kRe gks xbZgSA2) fcyksa ds çØe.k dh vc osclkbV ij fuxjkuh dh tk ldrh gS ftlesa fcyksa dh fLFkfr ds ckjs esa ns[kk tkldrk gS [kklrkSj ls ;g ns[kk tk ldrk gS fd mUgs a fdlh dkj.k ls vLohd`r fd;k x;k ;k ikl fd;k x;kA3) fcyksa dh çLrqfr ds fy, le;&lhek dh Li"V vuqlwph dk dk;kZUo;u ¼JO;&n`'; fcyksa ds fy, ,d ekg]lekpkj i=ksa ds fcyksa ds fy, nks ekg½] ftlds i'pkr~ nkok dh xbZ jkf'k esa ls çLrqfr esa nsjh ds vk/kkj ijdVkSrh dh tk ldrh gSA4) lwpuk Hkou ds Hkwry ij fcy çkIr djus ds fy, ,d lqfo/kk d{k ¼QSflfyVs'ku lsy½ cuk;k x;k gS tgka fcyçkIr fd, tkrs gSa rFkk fnukafdr ikorh nh tkrh gSA5) laoh{kk ds nkSjku çR;sd vLohd`r fcy ds fy, funs'k ¼ys[kk½ dh vksj ls i= ftlesa vLohd`fr ds dkj.k dkLi"Vhdj.k gksrk gSApy jgh cM+h igy% ys[kk Lda/k esa py jgh cM+h igy fuEukuqlkj gS%1) ys[kk çØe.k ¼çkslsflax½ rFkk laoh{kk dh vkmVlksflZaxA2) ys[kk laca/kh f'kdk;rksa ds fy, ,d gSYi&ykbu rFkk dkWy lsaVj dk xBuA3) lHkh Hkqxrkuksa ds fy, ;kaf=d fuf/k LFkkukarj.k ¼bySDVªkfud QaM~l VªkalQj½ esa ifjorZu] ftlesa çn'kZfu;ksa rFkkosru dk Hkqxrku Hkh 'kkfey gSA4) lHkh deZpkkfj;ksa dks dEI;wVj miyC/k djkuk rFkk lHkh Hkqxrkuksa dk çØe.k ¼ çkslsflax½ mi;qDr lkWVos;j dsek/;e ls djuk pkgs og lekpkj i=ksa ds fy, gks ;k JO;&n`'; ds fy, gksAAR 2011

Some higher taxa have disjunct distributions. They have uniquespecies found in nonadjoining regions. Examples include thelungfishes, with a single species in South America, a singlespecies in Australia, and three species in Africa.The few remainingilungfish species areevolutionary“relicts” <strong>of</strong> a timewhen lungfish werebroadly distributed.

The distribution <strong>of</strong> organisms or higher taxa today can beinfluenced by ecological requirements <strong>of</strong> the species, ,geologicalgbarriers that haven’t been crossed (e.g. mountains, deserts), or byhistorical factors - Extinction, Dispersal, and Vicariance.Extinction removes a taxon from a region where it was formerlypresent. (e.g. horses and relatives in North America, elephantrelatives throughout North America, and Northern Europe).Dispersal by individuals <strong>of</strong> a species expand the range <strong>of</strong> a taxon.Range expansion is the movement <strong>of</strong> a species across a favorablehabitat. Jump dispersal is movement across a barrier.In both starlings andcattle egrets an initialjump was followed by acontinuing rangeexpansion.

Historical BiogeographyStrict vicariance produces completelyconsistent patterns <strong>of</strong> phylogeneticdivergence and geographic separation.

Dispersal can be inferred when geologicevents precede cladogenic events.Dispersal can be concluded only when thepattern can’t be explained by vicariance.

Extinction complicates interpretations <strong>of</strong>vicariance and dispersal.

The Hawaiian Islands have formed from a series <strong>of</strong>volcanic eruptions on the submerged Pacific plate as itmoved over a “hot spot.” Islands are progressivelyyounger to south and east. Islands were colonized byspecies from nearby islands as they formed.A phylogenetic analysis <strong>of</strong> cricketssuggests that the oldest species arefound on the oldest islands.

Several groups <strong>of</strong>organisms are distributedfrom Africa toMadagascar, and toIndia. The distributionib ti<strong>of</strong> those organisms todaymay be explained bystrict vicariance - due towidespread distributionamong the southerncontinents beforeseparation.

Some groups have distributions consistent with an ancestralSome groups have distributions consistent with an ancestralGondwanan distribution with diversification after continentalseparation – a vicariant pattern.

The prosimians in Madgascar and Africa appear to havediverged long after the breakup <strong>of</strong> Gondwana. A pattern thatcan only be accounted for by dispersal.

The pattern <strong>of</strong> distribution amongspecies <strong>of</strong> chameleons is notconsistent with the breakup <strong>of</strong> thesouthern continents. It is bestexplained by origination inMadagascar (M) and dispersal toAfrica (A), the Seychelles Islands(SE) and to India (I).

Phylogeography is the description andanalysis <strong>of</strong> the processes that govern thedistribution <strong>of</strong> genetic lineages. Geneticanalysis is used to construct a geneticphylogeny and then the phylogeny is mappedonto geography.Classically there have been two hypothesesfor the evolution <strong>of</strong> humans, the multiregionalhypothesis - modern Homo sapiens evolvedsimultaneously throughout the old world fromarchaic Homo sapiens with exchange <strong>of</strong>genetic information by gene flow - and theout-<strong>of</strong>-Africa hypothesis - modern humansevolved in Africa and moved out replacingpreviously widely dispersed archaic humans.

Mitochondrial DNA analysis <strong>of</strong> modernhumans suggests that Asian, European,Australian and Indonesian populationsall share a common ancestor thatdispersed sed from Africa about 50,000years ago. Multiple dispersals out <strong>of</strong>central Asia appear to account forEuropean populations.

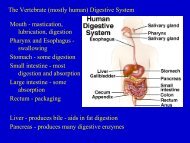

Ecological BiogeographyThe current distribution <strong>of</strong> a species over broad geographic areasmay be the product <strong>of</strong> past dispersal or vicariance, but the localdistribution ib ti <strong>of</strong> a species may be better explained by its tolerance <strong>of</strong>physical variables (soil pH, salinity), its requirements forsustaining a population (oxygen concentration, soil nutrients), itscompetitors for resources, or factors that reduce its ability to livein an area (predators, parasites, disease).Ecologists ask what factors limit the distribution <strong>of</strong> a species: Whydoes a species live in one area but not another?

Ecologists and evolutionary biologists are both interested inexplanations for broad patterns <strong>of</strong> species diversity.iCommonly, within any group <strong>of</strong> organisms there are morespecies in the tropics than at higher latitudes.

There are several possible explanations for this pattern:• Time hypothesis: tropical regions have remained largelyundisturbed since the K/T boundary while temperate zones haveundergone repeated glaciations i recently. The tropics have hadmore time for the evolution <strong>of</strong> more species.• Niche partitioning hypothesis: species in the tropics have more• Niche partitioning hypothesis: species in the tropics have morespecialized life-styles. Thus, more species can exist with a givenrange <strong>of</strong> resources.

• Resource hypothesis: the greater productivity in the tropicsallows a greater range <strong>of</strong> resources for species to exploit. Thusallowing more species to coexist.• Predation hypothesis: greater rates <strong>of</strong> predation, parasitism,and disease in the tropics results in less competition forresources and thus more overlap in resource use.Each hypothesis hasEach hypothesis hassome evidence tosupport it.

How many species can an area support? On islands, there is ageneral relationship between species diversity i and total area.This suggests there many be a maximum number <strong>of</strong> speciesthat an area can support - an equilibrium number.

MacArthur and Wilson have proposed that the species diversity<strong>of</strong> an area is determined by a balance between rates <strong>of</strong> speciesimmigration from other areas and rates <strong>of</strong> extinction.Small islands are lesslikely to receive randomimmigrants from amainland sourcepopulation. Populationson small islands are alsomore likely to go extinctdue to chance events.Thus large islands close to the mainland should have the mostspecies and small islands far from the mainland should have thefewest species. This idea has been broadly supported and isknown as the Island Biogeographic Theory.