Lutyens Garden Bench, The - Fine Woodworking

Lutyens Garden Bench, The - Fine Woodworking

Lutyens Garden Bench, The - Fine Woodworking

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

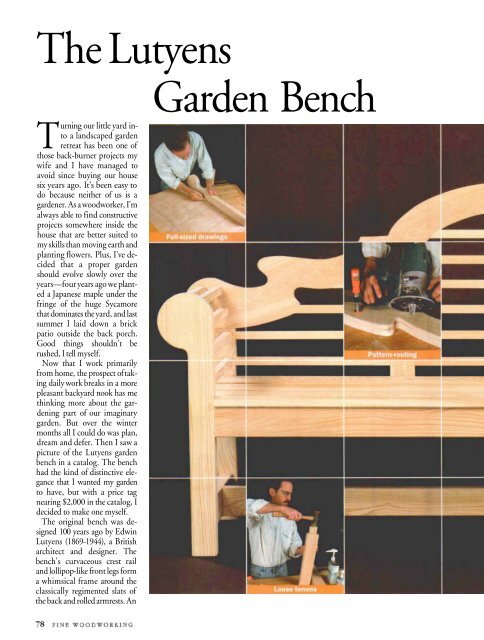

<strong>The</strong><strong>Lutyens</strong><strong>Garden</strong> <strong>Bench</strong>Turning our little yard intoa landscaped gardenretreat has been one ofthose back-burner projects mywife and I have managed toavoid since buying our housesix years ago. It's been easy todo because neither of us is agardener. As a woodworker, I'malways able to find constructiveprojects somewhere inside thehouse that are better suited tomy skills than moving earth andplanting flowers. Plus, I've decidedthat a proper gardenshould evolve slowly over theyears—four years ago we planteda Japanese maple under thefringe of the huge Sycamorethat dominates the yard, and lastsummer I laid down a brickpatio outside the back porch.Good things shouldn't berushed, I tell myself.Now that I work primarilyfrom home, the prospect of takingdaily work breaks in a morepleasant backyard nook has methinking more about the gardeningpart of our imaginarygarden. But over the wintermonths all I could do was plan,dream and defer. <strong>The</strong>n I saw apicture of the <strong>Lutyens</strong> gardenbench in a catalog. <strong>The</strong> benchhad the kind of distinctive elegancethat I wanted my gardento have, but with a price tagnearing $2,000 in the catalog, Idecided to make one myself.<strong>The</strong> original bench was designed100 years ago by Edwin<strong>Lutyens</strong> (1869-1944), a Britisharchitect and designer. <strong>The</strong>bench's curvaceous crest railand lollipop-like front legs forma whimsical frame around theclassically regimented slats ofthe back and rolled armrests. An

Full-sized drawings and accurate templateshelp break a classic design into manageable partsBY TONYO'MALLEYeye-catching and comfortablethree-seater, it's no wonder the<strong>Lutyens</strong> bench is still copied bydozens of outdoor furnituremanufacturers.Some reproductions I've seenhave no bottom stretcher at thefront or back, and others haveboth. As I sketched and workedthrough drawings, I began tonotice that a bottom stretchereven with the front legs wouldrestrict a sitter's feet from goingwhere they naturally want togo—under the seat a few inches.As a compromise, I positioneda stretcher under themiddle of the seat, tenoned intothe bottom side stretchers.I worked out the details of theentire bench using full-sizeddrawings. I drew the bench, atvarious views, directly onto-in. plywood. Because of themyriad joints, angles and curvesin this design, full-sized drawingswere crucial to making theproject run smoothly. <strong>The</strong> drawingshelped me not only to refinethe design of the benchbefore committing any cuts tolumber but also to figure out theconstruction and necessary orderof assembly.Choose an appropriate woodfor outdoor useReproductions of the <strong>Lutyens</strong>garden bench are typically,made of teak, but I ruled thatout immediately due to the cost.My bench would sit outsidepermanently because I didn'thave a place to store it indoorsover the winter, so weather resistancewas a main requirement.Spanish cedar is a goodmahogany-colored wood thatweathers better than real ma-

This classic bench design was built fromcypress to endure all four seasons. Loosetenons and dowel joints were all joined with aslow-setting, waterproof epoxy so that theentire bench could be assembled at once.hogany, but I couldn't find anylocally. I looked at several importedhardwoods being marketedfor deck building—ipefrom South America and jarrahfrom Australia among them—but these woods are very heavy,quite abrasive to tools and generallyhard to work. Highweight also helped me rule outlocally grown woods like whiteoak and locust.I settled on cypress for its lightweight, good moisture resistanceand moderate hardness. Itwas also available from a localsupplier at a good price and inthicknesses that would work—Iused 8/4 material for the benchframe and 4/4 material for theseat boards, arm slats and backslats. If you want to avoid planingrough lumber, cypress isavailable as dimensional lumberfrom many suppliers ofdeck-building materials.Start with the seat frame<strong>The</strong>re's no better motivatorwhen making furniture than actualprogress, so I like to startwith the easier parts of a projectand work my way up to themore difficult ones. In this casethe back of the bench was byfar the hardest part to make, so Idecided to build the rest of thebench first.For each back leg, I facegluedtwo pieces of 8/4 stock. I

FULL-SIZED DRAWINGS AID LAYOUTFRONT LEGREAR LEGFull-sized drawingslead to accuratetemplates.<strong>The</strong>drawings makeit easy to checkmeasurementsand make a templatefor thelegs. Simplymark out theprofile on theblank (left), thenbandsaw the legto shape (right).Mark legs at intersectionpoints. With thefront leg cut toshape, use aside-view drawingto mark outthe positionof the rail andstretcher (left).All frame mortisesare centeredon the stock andare in. thick(right).planed down the stock to in.thick (the actual thickness is notcrucial; just keep it as thick aspossible). I ripped the stockslightly oversized to 3 in., thenglued the slabs together. <strong>The</strong>seam is visible only from theside, not from the front or back.Structurally, either approachwould be sound, but my approachmade the front view alittle cleaner. I planed the rest ofthe 8/4 stock down to its final-in. thickness.I transferred the profile of theback legs from my full-sizedside-view drawing and cut themout on the bandsaw (see thephotos above). I sanded thebandsawn surfaces on my 6-in.edge sander, but a block planeand some hand-scraping wouldwork just as well.Both front legs can be cutfrom a single piece of stock,6 in. or wider, with the straightpart of the legs overlapping. Irough-cut the legs first, thenripped the inside edge of eachone on the tablesaw, stoppingshort of the top circle. <strong>The</strong>n Ibandsawed the final shape ofthe circle and the transition intothe straight inside edge.With all of the seat-frame partscut to size, it was time to cut themortises. Years ago, when I firstlearned woodworking, therewas a horizontal mortiser in theshop where I worked. With onesetup, this machine cuts mortisesin both parts that form a joint;a separate piece of wood isused for the tenon (called aloose tenon). In most cases it's alot easier than cutting a tenonand routing a mortise, and theresulting joint is just as strong.Since then, the idea of cuttingmortises with a plunge routerhas never caught on for me, andI now use the mortiser on myRobland combination machine(see the photo below) for al-DO COMBINATION MACHINES MAKE SENSE?<strong>The</strong> deal I got on my used Robland X31 combination machine seven years ago wastoo good to pass up. <strong>The</strong> Robland combines five tools: tablesaw with sliding table,jointer, planer, spindle shaper and horizontal mortiser. Moving from one task toanother can be time-consuming, but the tool is heavy duty and high quality. For mysmall shop and tight budget, the machine definitely has been worth the money.

most all joinery work, includingdoweling.I centered the mortises in the-in.-thick rails and stretchersand in the faces of the legs. Aftershaping the tenon stock andcutting the separate tenons tolength, I glued them into theends of all the rails and stretcherswith epoxy. One caution,however: Before gluing thetenons into the seat rails, dry-assemblethe legs and side rails. Ifthe complementary anglesformed by the back-leg cantand the rails are off, the jointsOne tenon fits all. <strong>The</strong> authormills tenon stock to thickness,rips it to width, then rounds overthe corners. By trimming them toshort lengths, he can make manytenons from one piece of stock.won't close perfectly. To solvethe problem, simply scribe anew cut line and recut the backends of the side rails and sidestretchers for a perfect fit. (Besure to recut the two intermediateseat rails at the same time.)Also, because the tenons onthe front, rear and side seat railsintersect, I mitered them so thateach is as long as possible. I cutthe curve in the seat rails on thebandsaw and—at long last, itseemed—dry-assembled thebench frame, less its back.<strong>The</strong> back is the mostdifficult section to makeGood design often leads to constructionand assembly conundrums,and it's certainly truewith the back of this bench. <strong>The</strong>visual centerpiece aroundwhich the bench is designed,the back is deceptively well integratedinto the rest of thebench's structure (see the drawingsabove). But the requiredassembly sequence was not immediatelyobvious to me. Lookingat the sturdy bench framedry-assembled, I wanted to gluesomething up. But each assemblysequence I considered ledto a dead end involving theback of the bench.After scratching my head fora long while, it became clearthat the entire bench, startingwith the back, would have to beglued up in one continuous assembly.It also would have beenpossible to glue up the backfirst and then the rest of thebench frame, but I opted for asingle glue-up. I chose anepoxy from West Systems andused a hardener with a slightlylonger open time than the company'sstandard hardener (seethe box on the facing page).First I made a full-sized drawingof the entire back. <strong>The</strong>n Imade a template for shaping thecrest rail, which is made of twopieces connected at the center-

ing the crest rail down ontothe stiles and also engage thedowels in the back slats at thesame time.I'm sure there are other solutions,but I decided that all ofthe slats attaching to the crestrail would be butt-joined andreinforced with countersunkscrews from underneath. Additionally,the slats under the centerarch would have to beadded after the main assemblyby half-lapping them over thecenter stile. Between epoxy'sgood gap-filling ability andcarefully predrilled holes for thescrews, these butt joints shouldhold up just fine.I cut all of the slats to fit withinthe assembled back frame. Toget the curved ends of the upperslats, I held them in positionand marked right off the crestrail where they intersect. I bandsawedand sanded the ends tofit snugly, After cutting the halflaps in the center stile and thetwo top slats, I used the sameprocess to fit these last two slats.I drilled the dowel holes for allof the slats on my horizontalmortiser.Build the rolled armsand attach the seatOnce the components of theback had been cut and the joineryfitted, I reassembled the entirebench dry (see the rightphoto below), then cut the armslats to fit. First I laid out the positionof each slat on the frontand back legs, then cut the slatssquare at the front and with a 6°angle at the back to correspondto the angle of the back (see thedrawings at left). I drilled anddoweled the ends of the armslats on my mortiser, thendrilled the corresponding holesin the back legs and crest railwith a hand drill using a bevelgauge as a guide (see the leftphoto below).After all that, the most essentialpart of the bench—theseat—still remained undone.<strong>The</strong> back edge of the rear-mostseat board is angled at 18° sothat it can snug up against theback legs and stiles. <strong>The</strong> frontHAND-DRILLED MORTISESRolled arms are attached with dowels.With the back dry-fitted tightly into place, youstill have to drill dowel holes for the slats thatmake up the rolled arms. To make sure theangle is correct, use a bevel gauge canted to6° to guide a handheld drill.

ATTACHING THE SHAPED SLATSFinishing the back. After themain components of the benchhave been glued up, the smallerslats can be set into place.A smooth fit. Using a dado set onthe tablesaw, the two top slats arenotched to fit over the center stile.Scribing the back slats. <strong>The</strong> upper slats on the back are scribed for atight fit. A bandsaw is used to cut them to shape, but final shaping isdone with rasps and sanding machines. <strong>The</strong> shaped ends of the slats arescrewed into place from underneath.seat board is narrower and sitsflat on the square edge of thefront seat rail. <strong>The</strong> four middleseat boards are identical. Topromote rain runoff from theseat and reduce the likelihoodof splinters, I rounded over thetop edges of the seat boardswith a -in. roundover bit.Using exposed screws in thetop of the seat boards woulddetract from the refined look ofthis bench and give water aplace to pool. And screwing upthrough the curved rails wouldrequire different-sized screwsor counterboring a differentdepth for each board. So I attachedthe seat boards to theframe from above with galvanizeddeck screws. <strong>The</strong> holeswere counterbored, and I gluedplugs in them for a clean look.Before the final glue-up, Isanded all of the bench parts,keeping the joined areas goodand flat. I went over all fouredges of the arms slats with an-in. roundover bit. I used a-in. roundover bit to soften theexposed parts of the curvedcrest rail and the front legs, beingcareful to stop at the jointseams. After sanding, I assembledthe bench with epoxy anda lot of clamps.Well, my garden retreat is stillcomposed of a brick patio, aJapanese maple and a fewpotted plants. Only now it'salso graced by a quite comfortableand distinctive bench. ButI'm afraid it will take some inspiredlandscaping and probablymore than a few years todevelop a garden that's worthyof the bench.Tony O'Malley is an editor, writer andwoodworker in Emmaus, Pa.<strong>The</strong> last touch.Working from theback toward thefront, the authoruses spacers andscrews down theseat. Once inplace, bungs areepoxied intoplace over thecountersunkscrews.