Staffrider Vol.3 No.4 Dec-Jan 1980 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.3 No.4 Dec-Jan 1980 - DISA Staffrider Vol.3 No.4 Dec-Jan 1980 - DISA

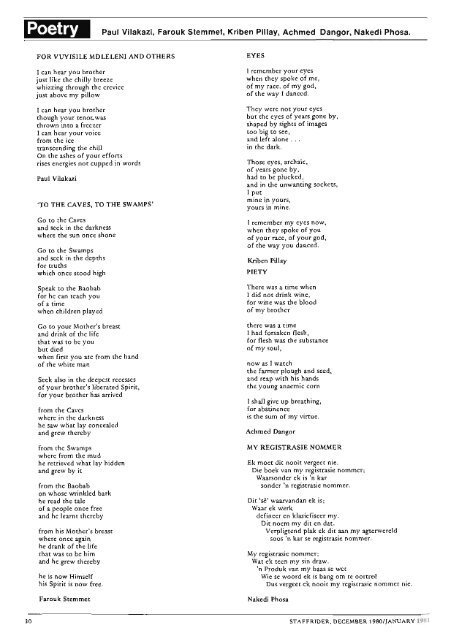

PoetryPaul Vilakazi, Farouk Stemmet, Kriben Pillay, Achmed Dangor, Nakedi Phosa.FOR VUYISILE MDLELENI AND OTHERSI can hear you brotherjust like the chilly breezewhizzing through the crevicejust above my pillowI can hear you brotherthough your tenor, wasthrown into a freezerI can hear your voicefrom the icetranscending the chillOn the ashes of your effortsrises energies not cupped in wordsPaul Vilakazi'TO THE CAVES, TO THE SWAMPS'Go to the Cavesand seek in the darknesswhere the sun once shoneGo to the Swampsand seek in the depthsfor truthswhich once stood highSpeak to the Baobabfor he can teach youof a timewhen children playedGo to your Mother's breastand drink of the lifethat was to be youbut diedwhen first you ate from the handof the white manSeek also in the deepest recessesof your brother's liberated Spirit,for your brother has arrivedfrom the Caveswhere in the darknesshe saw what lay concealedand grew therebyfrom the Swampswhere from the mudhe retrieved what lay hiddenand grew by itfrom the Baobabon whose wrinkled barkhe read the taleof a people once freeand he learnt therebyfrom his Mother's breastwhere once againhe drank of the lifethat was to be himand he grew therebyhe is now Himselfhis Spirit is now free.Farouk StemmetEYESI remember your eyeswhen they spoke of me,of my race, of my god,of the way I danced.They were not your eyesbut the eyes of years gone by,shaped by sights of imagestoo big to see,and left alone . . .in the dark.Those eyes, archaic,of years gone by,had to be plucked,and in the unwanting sockets,I putmine in yours,yours in mine.I remember my eyes now,when they spoke of youof your race, of your god,of the way you danced.Kriben PillayPIETYThere was a time whenI did not drink wine,for wine was the bloodof my brotherthere was a timeI had forsaken flesh,for flesh was the substanceof my soul,now as I watchthe farmer plough and seed,and reap with his handsthe young anaemic cornI shall give up breathing,for abstinenceis the sum of my virtue.Achmed DangorMY REGISTRASIE NOMMEREk moet dit nooit vergeet nie.Die boek van my registrasie nommer;Waarsonder ek is 'n karsonder 'n registrasie nommer.Dit 'se' waarvandan ek is;Waar ek werkdefineer en klasiefiseer my.Dit noem my dit en dat.Verpligtend plak ek dit aan my agterwereldsoos 'n kar se registrasie nommer.My registrasie nommer;Wat ek teen my sin draw,'n Produk van my baas se wetWie se woord ek is bang om te oortreeDus vergeet ek nooit my registrasie nommer nie.Nakedi Phosa30 STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER 1980/JANUARY 19^ i

THE SUNAn extract from a novelby Mongane Seroteillustrated by Mpikayiphelii-oli...ilil,.The sun, its rays clinging to the trees, the branches andleaves, was rising up, over Jukskei river. The sky was yellowwhere the sun was peeping, and becoming silver as the raysmoved and moved, spreading further into the vast sky. Thesky is an empty hole? That is disappointing! I walked on.Somewhere a dog was barking, dogs were barking. I thoughtthey may be chasing a horse, a donkey or a cow. I could alsohear drums and whistles. I walked on, down Vasco da GamaStreet; past 17th Avenue. The heat of the sun hit me straighton the forehead. An old lady wearing a sombrero whichalmost obscured her view passed, carrying a spade and abucket. Her legs carried her as if they were creaking. She wasbent forward, miraculously managing not to crash down onher face. Slowly she trod on, and this took her away on herjourney, away from the dead.I went through the gate. Ah, if graves could talk! Therethey were, spread throughout this vast field, their numberplatessticking up in the air, as if they were hands wavingbye-bye. The tombstones looked like miniature sky-scrapers.Some tombstones said something about wealth, others wereordinary, and some graves had no tombstones at all. Birdswere singing. A cow mooed. Cars roared. But, the silence wasstubborn. It stuck in the air, looming over the heaps of soiland those who could still walk. Somewhere in an emptypatch, a car without wheels, if we still call it a car, hadturned colourless: its seats were ashes, smoke still rosefrom somewhere around its bowels. The car stood there,proclaiming its death too. As I approached it, I realised it wasthat year's Valiant. They took what they wanted from it, andleft it there. The owner, probably white, will talk to the deadabout it. I went along the road.There are always many people, children, women, men,families, widows, widowers, all of them busy, busy with thegraves, silent, weeding, putting fresh flowers into vases, manypeople, scattered throughout the cemetery, early on aSunday morning. The silence here is graceful. The silencesounds like the song of the birds, of the trees, of the wind;something about the silence of this place suggests, makes onesuspect that God, or maybe the dead, are looking at one,listening to one, about to talk to one, just about to do it —but they never do. Women, some in fresh black mourningclothes; all of us, for some reason, wearing casual clothes —men trying to walk straight, holding spades and rakes;children, forever children, now and then playing, nowhaving to follow the elders, now being scolded; families,holding to each other by freshening the graves of their beloved,weeding the sides of the graves; a hymn, a desperateprayer, whispers, the wind, the silence of the dead.I was sitting on the grave of my grandfather. I fought thethought that nagged me, which wanted to know whether heheard me when I asked about Fix; and also, when I told himthat I was getting tired of going to the shebeen; and that Iwouldn't go to church. I fought this thought. I will fightfight it forever. By coming here, every Sunday, I will fight it;I know he is listening, and asking whether I was willing tochange. That is where the trouble started — was I willing tochange?I stood up to go.I was washing my hands near the gate, when I saw him.|!§§i ; :-; : .The water wet my trousers. I thought shit, people willthink I peed on my trousers. Where had I seen this old man?He was walking slowly towards the gate. His backside swungleft-right-left-right, and now and then he stood to look at thefield of tombstones and number plates. It was as I got closerthat I recognised him.'I see you, Father,' I said.'Yes.' He stopped and looked at me. He was breathingheavily. His eyes were fixed on me, searching. His hat,flipped over to the back of his head, revealed white, whitehair, which in turn joined the white, white beard. His eyeswere wet and grey. They sure revealed how weary he was. Icould not tell whether he was frowning or whether thosewere permanent old-age folds on his face. He kept staring atme, in silence, then he looked away.'You boys have no sense,' he said. He looked away andwith his stick pointed at the car, which was still smoking.'Why don't you throw that thing in the street? We want torest here, not to be burdened with your foolishness. Look atthat!' He looked at me.'Huh?' I was still trying to search for something to say.'They burn the grass when they clean the rest place, andthen you come and throw stolen cars here? What a curse!'He began to walk. I walked next to him, slowly. He stopped.'You see that tall tombstone?''Yes,' I said.'Nkabinde is resting there.' He began to walk again. 'Youknow Nkabinde? He used to own a shop near Eighth Avenue,he died last year, they say he had bad lungs or something. Hehad a big funeral. Yes, he was a good man, a man of thepeople.' He stopped to take a look again. 'I never used tounderstand why he said we should buy properties fromthe old ladies and from anyone else who wanted to selltheirs. You know, I used to think he was greedy, but no, hehad a head. If we did that time, these Boers would not havetaken our place so easily, like they have. Look at all that!'He pointed with his stick towards Alexandra. For somereason or another, every time I looked at Alexandra fromSTAFFRIDER, DECEMBER 1980/JANUARY 1981 31

- Page 2: Introducing theSTAFFRIDERPOSTER SER

- Page 5 and 6: Voices from the GhettoMrs T H, anof

- Page 7 and 8: THE CANE IS SINGINGBY NARAIN AIYERT

- Page 9 and 10: PoetryThabo Mooke, Kedisaletse Mash

- Page 11 and 12: mess. His mind clouded for a moment

- Page 13 and 14: 'My Dear Madam...by Nokugcina Sigwi

- Page 15 and 16: Poor Business for the ArtistBy Nang

- Page 17 and 18: Staffrider Gallery Goodman Mabote,S

- Page 19 and 20: D.John Simon.IN MEMORIAM-BERNARD FO

- Page 21 and 22: Charles Rukuni64 We are up againstC

- Page 23 and 24: DramaThe Ikwezi PlayersJob MavaA wo

- Page 25 and 26: JOB: And anyone would think this wa

- Page 27 and 28: Tribute to Ralph Ndawo

- Page 29 and 30: slowly.My wife, Noamen, was at home

- Page 31: ZIZAMELE:That's what I'm asking you

- Page 35 and 36: they fight/ he said, wiping his for

- Page 37 and 38: 6JT/WEST\ Story by Ahmed Essop Illu

- Page 39 and 40: landish appearance of the man — h

- Page 41 and 42: Mhalamliala1981By Mothobi Mutloatse

- Page 43 and 44: the man in question was really his

- Page 45 and 46: Staff rider WorkshopPOLITICS AND LI

- Page 47 and 48: IN THE SUNContinued from page 34bus

- Page 49 and 50: • Bob Marley is theblack prince o

- Page 51 and 52: BACKHOMEMIRIAM MAKEBAHUGH MASEKELAA

PoetryPaul Vilakazi, Farouk Stemmet, Kriben Pillay, Achmed Dangor, Nakedi Phosa.FOR VUYISILE MDLELENI AND OTHERSI can hear you brotherjust like the chilly breezewhizzing through the crevicejust above my pillowI can hear you brotherthough your tenor, wasthrown into a freezerI can hear your voicefrom the icetranscending the chillOn the ashes of your effortsrises energies not cupped in wordsPaul Vilakazi'TO THE CAVES, TO THE SWAMPS'Go to the Cavesand seek in the darknesswhere the sun once shoneGo to the Swampsand seek in the depthsfor truthswhich once stood highSpeak to the Baobabfor he can teach youof a timewhen children playedGo to your Mother's breastand drink of the lifethat was to be youbut diedwhen first you ate from the handof the white manSeek also in the deepest recessesof your brother's liberated Spirit,for your brother has arrivedfrom the Caveswhere in the darknesshe saw what lay concealedand grew therebyfrom the Swampswhere from the mudhe retrieved what lay hiddenand grew by itfrom the Baobabon whose wrinkled barkhe read the taleof a people once freeand he learnt therebyfrom his Mother's breastwhere once againhe drank of the lifethat was to be himand he grew therebyhe is now Himselfhis Spirit is now free.Farouk StemmetEYESI remember your eyeswhen they spoke of me,of my race, of my god,of the way I danced.They were not your eyesbut the eyes of years gone by,shaped by sights of imagestoo big to see,and left alone . . .in the dark.Those eyes, archaic,of years gone by,had to be plucked,and in the unwanting sockets,I putmine in yours,yours in mine.I remember my eyes now,when they spoke of youof your race, of your god,of the way you danced.Kriben PillayPIETYThere was a time whenI did not drink wine,for wine was the bloodof my brotherthere was a timeI had forsaken flesh,for flesh was the substanceof my soul,now as I watchthe farmer plough and seed,and reap with his handsthe young anaemic cornI shall give up breathing,for abstinenceis the sum of my virtue.Achmed DangorMY REGISTRASIE NOMMEREk moet dit nooit vergeet nie.Die boek van my registrasie nommer;Waarsonder ek is 'n karsonder 'n registrasie nommer.Dit 'se' waarvandan ek is;Waar ek werkdefineer en klasiefiseer my.Dit noem my dit en dat.Verpligtend plak ek dit aan my agterwereldsoos 'n kar se registrasie nommer.My registrasie nommer;Wat ek teen my sin draw,'n Produk van my baas se wetWie se woord ek is bang om te oortreeDus vergeet ek nooit my registrasie nommer nie.Nakedi Phosa30 STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 19^ i