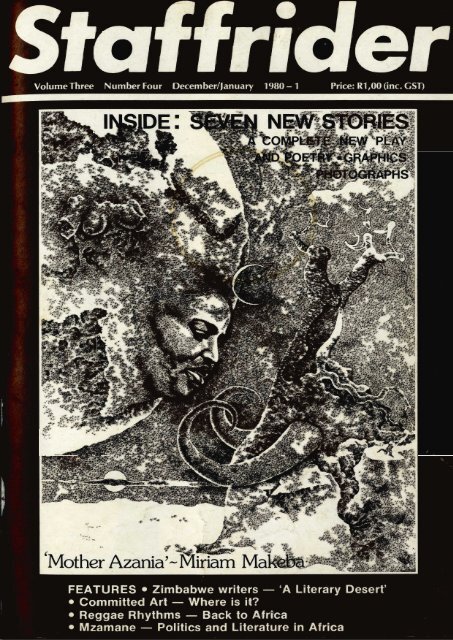

Staffrider Vol.3 No.4 Dec-Jan 1980 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.3 No.4 Dec-Jan 1980 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.3 No.4 Dec-Jan 1980 - DISA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Introducing theSTAFFRIDERPOSTER SERIESStaff riderintroduces a powerful new seriesof posters of peoples' heroes — leadingfigures in black cultural and political life —drawn by Nkoana Moyaga and representingthrough these portraits key elements of ourhistory, our present, and our future.The posters are 50 cm x 70 cm wide andprinted in the sepia of the origionals.ON SALE NOW ARE <strong>Staffrider</strong> PosterSeries No 1 (Bantu Steve Biko) and No 2(Miriam 'Mother Africa' Makeba, reproducedon the cover of this issue) at R2,00 each.New Titles in the<strong>Staffrider</strong> SeriesMZALA, Mbulelo Mzamane,<strong>Staffrider</strong> Series No 5 - R3.50AMANDLA, Miriam Tlali,<strong>Staffrider</strong> Series No 6 - R3,957VS4&*The Stories ofMBULELO MZAMANE

PoetryNjabulo Simakahle Ndebele, Amelia House, Nkathazo kaMnyayiza.THE REVOLUTION OF THE AGEDmy voice is the measure of my lifeit cannot travel far now,small mounds of earth already bead my open grave,so come closelest you miss the dream.grey hair has placed on my browthe verdict of wisdomand the skin-folds of agebear tales wooled in the truth of proverbs:if you cannot master the wind,flow with itletting know all the time that you are resisting.that is how i have livedquietlyswallowing both the fresh and foulfrom the mouth of my masters;yet i watched and listened.i have listened tooto the condemnations of the youngwho burned with scornloaded with revolutionary maximshot for quick results.they did not knowthat their angerwas born in the meeknesswith which i whipped my self:it is a blind progenythat acts without indebtedness to the past.listen now,the dream:i was playing music on my flutewhen a man came and asked to see my fluteand i gave it to him,but he took my flute and walked away.i followed this man, asking for my flute;he would not give it back to me.how i planted vegetables in his garden!cooked his food!how i cleaned his house!how i washed his clothesand polished his shoes!but he would not give me back my flute,yet in my humiliationi felt the growth of strength in mefor i had a goalas firm as life is endless,while he lived in the darkness of his wrongnow he has grown hollow from the grin of his crueltyhe hisses death through my flutewhich has grown heavy, too heavyfor his withered hands,and now i should smite him:in my hand is the weapon of youth.do not eat an unripe appleits bitterness is a tingling knife.suffer yourself to waitand the ripeness will comeand the apple will fall down at your feet.now is the timepluck the appleand feed the future with its ripeness.Njabulo Simakahle NdebeleMR WHITE DISCOVERERto cover your shameyou tiedmy sunkissed breaststiedimprisonedmy swinging breastsnowwhenearthlightmerges intomy black bodythenphantom loveryoucomeunleashmy breastswhite feetdancingout of stepwraptrapmy legsimmoralityactssucksmy milkButMr Whiteyno bloodfeversthrough myuntuned bodyNo moreno moretonight'slastmoonkisses on breaststomorrowmy beadstuneto sunkissedswinging breastsMr White discoverercoveryour shameAmelia Housedear siryou came to megun on hipto ask me aboutmy political beliefsmind your sondoesn't come to minebomb in pocketto ask himabout his political beliefsIT WILL BLOW HIM TOPIECES!nkathazo kaMnyayiza2 STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 198

Voices from the GhettoMrs T H, anoffice cleaner inJohannesburg,went to talk toMiriam Tlaliabout survival inthe dark hoursbefore THEFIRST TRAINFROM FARADAYMrs T.H. has had two previous jobs as acleaner. Now she's started a new one atRanleigh House, working for BCS, oneof the cleaning companies. She toldMiriam Tlali that it was . . .. . . the same old story. When we knockoff at 2.30 a.m., we have to go. There'sno mercy. Many* people in many placeshave been assaulted, people who workat night, meeting with ducktails andtsotsis — many, many people. I don'tknow about Ranleigh House becausewe've only just started there. But in allthe other places, we have been hearingof many of God's people who have beeninjured. Others we see passing nearwhere we work on their way out, goingto ... we don't know where. Now, oneasks oneself, just what happens to thesepeople? We can't go to Park Station; wemay not sleep on the benches. We maynot sit in the waiting-rooms. We muststand outside. Even when there's a trainon the platform, we may not board it.Now we wonder where we must go becausein the locations at that time it isrough. Even then, where will you go atthat time? Most of the time you are theonly one in that neighbourhood whereyou stay. It is like that too in RanleighHouse.At 2 a.m. what happens; do theycome and sign you off?Yes. Someone gives us the order toleave. We have a white woman supervisor.When we go, she comes and lets usoff.Now the cleaners; is it only womenthat they employ?Yes. It's only women who are cleaners.Some come from Diepkloof;others from Naledi, from everywhere.The supervisor is also a woman. But shehas a car, you see.There are companies of cleaners.Many firms. These have different names.One is called National, another is BCSand so on. You work until a certaintime. It matters not whether it's rainingor icy cold, there's no shelter for us.photo, Lesley LawsonIt is they who must provide shelter,isn't it?Yes. How we get home, they are notbothered about. That is none of theirconcern. You must see what to do.Whether you are assaulted or not, isnone of their business. At one time, I'veforgotten what year it was, a cousin ofmine was working at this Braamfontein'thing'(She raised her arms and pointedupwards with her palms clasped together).Which thing? The Hertzog Tower?Yes. The tower. She was just leavingthat place, early, when she was molested.It was only after they learnt that shewas seriously ill and in hospital with badwounds that the whites there said: 'Allright, you cleaners can wait on thepremises until it is safe to go home.'Those are the difficulties under whichwe work during the night.Now this cleaning you do. When doyou do it — during their absence?Yes. We clean after the officeworkershave left. Only the 'securities'are present./ thought it was the black male workerswho do the cleaning.No. It's we, the women, who do it.When do you start?Six.How do you do it; do you usemachines?Yes. We use Hoovers.Now, what happened to you oncewhen you alighted from the bus?When I got off the bus I met tsotsis.It was my usual practice to run veryfast, as fast as I could, in the directionof where I live. On this occasion, by thetime they caught up with me, I wasalready near my house. The bus driverdidn't stop at the official bus stop butinstead, he used to drop me at the cornerof the street where I live. They musthave noticed that. They hid and waitedat the house near the corner. One ofthem tried to reach for me and pull metowards them. Fortunately at that timeI had armed myself with . . . you know,these spiked iron flower holders . . . (Inodded) . . . Yes, the steel ones. I hadone of those, and I implanted it into hisforearm (She indicated the spot on herown arm.) . . . and when he withdrewand yelled, 'Ichu-u-u!' I got the chanceto run for safety. Then I realised that inspite of being clever, I'll get hurt seriously.It was after that incident that Idecided to stay at Park Station . . . Outside.Then I used to take the first trainfrom Faraday to Naledi and stay insideit. It would travel up and down, to andfro like that with me, until it was safe toget off at Nancefield and go home.(We both laughed softly and shookour heads.)We are laughing, but this matter isnot amusing at all. It's very sad indeed.Yes, but what can we do? Thenyou'd hear passengers say to me: 'You'llget hurt in the trains here; going up anddown alone, and a woman for thatmatter.' They were male passengers asusual at that time. Then I wouldanswer: 'What can I do? I've got to tryand save my life as I work. I have towork; I have no husband.'What about children? Haven't yougot a son to fetch you from the busstop? But then he, too, could easily oversleep and not fetch you . . .No; not that. He, too, can beassaulted while coming to fetch me. For

'•We have to pay for thetrain and bus fares andalso the meals we eatfrom the R34,00 perfortnight that we get ...There's not much we cando with that R34.00."photo, Ralph Ndawoinstance, there's another man whosename is Ngubeni. We attend the samechurch. He stays in Mofolo Village. Hisdaughter works for a bakery. She goesto work late at night and knocks off atnight. This poor man made it a point totake her to Ikwezi Station. Every nightat 8.30 p.m. he fetches her from thestation. One night, two months back,after he had taken her to the station. . . you know it was very dark as it waswinter ... on his way back, he met the'boys'. There were eight. What did theydo to him? If it were not for the factthat God gave him power . . . then Idon't know. With the stick he was carrying,he summoned all his courage andfought like mad. He fought for his life;for 'final'! When these boys realised thatthis old man had beaten them, one ofthem tripped him. That was when theygot the chance to overpower him. Theytripped him and dropped him onto theground. But he fought them even as hewas lying on the ground. One of themproduced a knife and tried to stab him,but he had seen him already and hegrabbed the knife. They then clubbedhis head and he sustained serious headinjuries. It all happened because he triedto save his daughter's life. There aremany more people who have beenstabbed or killed because they have tocome from work too early or too late atnight.Obviously this kind of work hasmany risks. How much money are youpaid for it?BCS only pays us R34.00.Per week ?No, every two weeks. We are holdingon because . . . What shall we do? Wehave children and grand-children. Wehave to send them to school. How arewe to feed them? There's not much wecan do with that R34,00. We complainbut it does not help. How much have webeen 'crying'? It's long but (she shrugsher shoulders) how do we pay rent? Themoney only pays the rent and for a fewbags of coal. We just go on. There'snothing we can do with it.It's good you spoke about this.It's no good keeping quiet. I've realisedit. It's these people who speak lies,telling strangers to Soweto that we livevery happily; we eat and drink, andthere is nothing we lack. They are theones who are sell-outs. They tell thewhites all sorts of untruths about ourlives here. You can see. Here in WhiteCity Jabavu, they paint the outsidewalls of the houses, the houses along themain roads, so that when the very 'big'ones come, they can deceive them andsay: 'Can you see that? We are paintingthe houses for them. You can see thatthere's nothing they want that theydon't get.' They only clean those housesalong the roads instead of letting themcome right inside and see the filth allaround.You know, I never thought of thismatter of office-cleaning. At first, itused to be men who were doing thework, wasn't it? I was aware of nurseshaving to do night duty, but notcleaners. What has happened to the menwho used to do it?You know, the men and women whodo the cleaning of the flats and so on dothe work during the daytime. It is theoffices which have to be cleaned atnight because during the day, they arebeing used./ see. What about your train and busfares; do they pay for those?No. We have to pay it from theR34,00 per fortnight that we get. . . It'sfor the train and bus fares and also themeals we eat.Mind you, even Carlton Centre, bigas it is, the people who clean it also haveto go out of there at that awkward time,in the night, at two o'clock. They haveno shelter for the cleaners.Just reckon how far Ranleigh Houseis from the station. At times we movethere and come across 'ducktails'; whitemen looking for black prostitutes. Theymistake us for street-walkers. They tooare an additional menace. They drivealong the streets next to the pavements,following us and making advances;enticing us to go into their cars. Younever know what the real intention is.As soon as one disappears round thecorner, another one appears. •PoetryPASSION OF A MAN IN LOVEhe is a man of the bushput there between loveand deaththe son to a heart-ached motherhe likes to smile at photographers(to prove he is alive and fit)smiling as i dowhen my gal says we belong to theworldhe is the man of the nighthe walks in the darkin ice-cold alleysof man's freedom roadhe does wish to be presentwhen mother calls us for supperhe is the man of the bushput between dark and lightby passionthe passion of a man in lovein lovewith mankindP.S.how many suppers do i enjoywith my mind on the meal?Senzo Malingafrom THE FORGED NEGATIONtheycame at nightunending marathonof nightmaresthe moon pale substitutefor the blazingtorchthe babiesgrow knowingblind faithwon't bringbackour godsonlybrave untremblingwarriorswill bringbackour godsNkos'omzi NgcukanaII

THE CANE IS SINGINGBY NARAIN AIYERThe cane is singing. All along it issinging: to the left, from where I am sittingin this train on my way to the bigcity to visit my children, to the rollingland where the sea begins, and to myright, into the interior where the sunsets. The cane is singing, but it is a sadrefrain that the cane is singing.They first landed on these shores in1860. Some were eager to come. Otherswere eagerly brought. That is why thecane is singing now. The mills are grindingand the sugar is pouring down thechutes, the quotas are increasing and onil return from Durban this train willhave many men from the Transkei in itsmany bellies, coming to this singingsugar-cane land. The chairman of theBoard reports a net profit, after tax, oftwo comma five. Sweet melody to theshareholders. No shares for me, for myfa her and his father before him and mychildren and their children after them.I-or us only the bitter notes of this sadsong, this soul-searing song that the caneis singing.Some were indentured. Others werepassenger immigrants. They came andthey worked. Nay, they toiled and theyslaved till their loin cloths were meltedoff their sweaty, swarthy backs. Theholes in which they lived were theirhomes but there was ample space in thecorners, if there were corners, to storemaster's ration of dholl, wood and coal.They awoke in the morning and raisedtheir hands to the rising sun — the sunlose from the East. That is where theycame from. Would they go back there?Mo, they must pick up the hoe, thesickle and the cane knife and go to themaster's farm. They must cut and thrustand dig and trench and rake and ploughand fetch and carry and bend and breakso that the cane may grow and sing asweet song for the master. Melodious:two comma five after tax.Black they were and some were fairwhen they came. Complexioned by theblood of their forbears from differentparts of their mother country butmostly from the South. But now theywere blackened even more as the sun'srays flame-seared across their bendedbacks. The heat can be as intense here asit was there. So many laws, regulations,conditions. Amendments to laws, regulations,conditions. Interpreters. Thumbprints.They just called the wholebloody thing 'GRIMIT. And so manysirdirs to see that their backs werebended, men, women and children. Yes,children of the children of our motherIllustration: Gamakhulu Dinisoland. And a hard time they had of it.But their spirit of the Upanishads andthe Bhagvad Gitas and the Pooranas andthe Shivas, and the Argunas and theSaraswatis prevailed. The invocationsand the incantations.The holy pilgrimages to holy shrines.And they remembered, too, the defeatof Ravana and they told their childrenthe story of Rama and Sita. The ritualsand the ragas of their ancient land theybrought with them and they sang anddanced in honour of their deities.They taught their children never toforget the golden languages of their owncultures but with equal fervour theyfinancially assisted the masters of theirnew country to teach their children thethree r's in the English language, thatthey might earn a living. So many'Government-Aided Indian Schools'.And only the other day, someone saidthat they do more to preserve and promotethe English language, the highideals and the noble values of the Englishtradition, than their Englishspeakingcompatriots themselves.Gradually, so gradually, some menwere taken off the fields and put intothe mills. The women and the childrentoiled on in the fields. Designation —'field workers'.The water place was the meetingplace. Communal taps, they calledthem. They met and they married. Thelavatories were communal too. You satSTAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981 5

next to your neighbour in the lavatory— there are still such ones to this day —you saw his private parts and he yours,and you discussed the prospects of yourson marrying his daughter. There wassome talk about caste. You farted outthe aches of yesterday's toil and heemptied his bowels and thought ofgoing to collect rations from master tofill the bowel again. Such were thegoings and comings of those times.Their numbers grew. Their problemstoo. Some bought, others sold out.Some lived in the quarters provided forthem, dingy holes with a few puny slitsfor ventilation, dunged floor, meagrerough furniture, brassware and the holylamp, faithfully and regularly polished.Their problems — working conditions,their options if any, their housing, theirwages, their right to buy, own and till apiece of land, their right to travel —received a wider and wider audience andthey became a problem, the 'IndianProblem' for debate at national and internationalforums. A Mahatma wasborn on a station platform in Pietermaritzburgand years later 'The IndianProblem' was a perennial item on theUnited Nations Agenda.As the train passes yet another sugarmill, I begin to think of the many youngmen and women from this particularindustry who had gone on to the outsideworld, to new fields, to new pastures,to find for themselves new comfortsand new glories.From the sugar fields some went intothe black mines further North. Othersbecame known throughout the distantworld as growers and exporters of bananaspar excellence. Master and hisMissus had a regular supply of the finestvegetables and fruit for the dinner table.Market gardeners. Pineapples. Tobacco.Some went fishing and master's piscatorytastes were nourished. A few tastedthe sweetness of growing their ownsugar on a piece of their own land.Some went to work in factories ofanother kind — some worked on therailways, others on the roads. Manyothers went to work in the hotel toserve master with the fish, the pineappleand banana and the tomato and lettuceand lit his pipe for him and carried theportmanteau upstairs for missus. Tenshillings a month, then. Now onehundred rand. 'They also serve whostand and wait.' Others answered thecall of <strong>Jan</strong> Christiaan Smuts to fightagainst Hitler and save democracy andthose who returned were thanked bythe Oubaas and given a bicycle to ride intheir twilight years. May their souls restin peace.'Government-Aided Indian Schools.'With the passage of time, hundreds ofthem. Thousands of young men andwomen responded to the call of theprofessions, commerce and industry.Into the wards as doctors, as nurses, aslaboratory assistants. Into the trainingcolleges and the universities. Teacherslawyers, clerks, factory hands, shopassistants. Transport and trade. Dauntingodds. Priceless talent. The skilledand the semi-skilled. Doors open anddoors shut. Many of them are now indifferent parts of the world, their trueworth recognized, their human dignityrespected. Sons of their land, Ons SuidAfrika! And now some of them arebeing recruited for the country's navy.'Duke et <strong>Dec</strong>orum est pro patria mori'?Their fathers queue for jobs and a fortunatefew are at the Ocean Terminal ontheir way to the land of their forbears —a holiday — a cherished dream cometrue. Into banking, insurance and thehotel industry. They make their mark.The Minister of Indian Affairs says at apublic function they are a pricelessasset, an integral part of the South Africannation but must develop separately.Garland please.What do I think as the train rumbleson towards the big city and we pass thismill and that siding, this village and thatsugar baron's estate. The rivers flowhere as they do there. There the Ganges,the Indus, the Brahamaputra, theGodaveri and the Kaveri. Here theTugela, the Umvoti, the Umgeni, theUmkomaas and the Umzimkulu. Somuch water has flown under the bridge.That's what I think. And the canegoes on singing. A compassionatepeople. A religious people. A law abidingpeople. Infinite capacity for suffering;unquenchable thirst for knowledge;stoical acceptance of iniquities; doneout of house and hearth; uprooted; brokenhomes, suicides; limited travelrights; limited jobs; cannot bring bridefrom land of their forbears; cannotenter this university, that theatre;cannot grow bananas — land requiredfor housing: Chatsworth for Indians; noelectricity for the people in that barracksin this sugar mill; no monetaryassistance for widow of man that gavethirty seven years of his life to make thecane sing; no passport for that man whodefends the highest ideals and thenoblest virtues of Western Christiancivilization; the temple and the marketto make way for new roadways; fromthe city to Chatsworth to maintain ourrevered land, sacred and dignifiedseparateness; do not visit your friendKhumalo in Umlazi without a permitand your friend Dirk in Vryheid withouta permit, for the law respects yourseparateness; Tin Town and poverty onthe banks of the Umgeni; overcrowding,malnutrition, shebeens andknifing in Chatsworth township.The glossy magazine carries a pictureof a beautiful house, a beautiful spouse.The Minister of Economic Affairs saysat a public function that as a communitythey are second to none when itcomes to self help — Garland please!The train rumbles on towards the bigcity and the cane sings on. Here andthere I pick up a sweet note or two butmost of the notes are sour, bitter. Howlush and green is the cane, mile uponmile in this fertile land bordering theIndian Ocean. They worked there beforethe turn of the century, theirgrandchildren and great grandchildrenstill work there. Vast hectares of sweetgreen monument to their monumentalefforts. Occasionally I pick up a wordfrom the song which says 'voteless' andagain a prickly 'voiceless'. My gnarledhands, my aching back; I feel the weightof it all on my shrinking shoulders, forin the furrow where the cane grows, ranthe blood and the sweat of my forbears,my blood and sweat and the sweat andblood of my children.This morning's newspaper headlinereads 'Sugar pact is worth R300 millionto Republic' I too should like to rejoicebut I cannot, for the song of the sugarcane is a sad refrain for me.Footnote:'Sirdar' means a foreman or supervisor.'Grimit' refers to Immigration lawsand conditions attaching to the employmentof Indian immigrants in thesugar belt of Natal.Garlanding is a traditional Indiancustom. Usually reserved for reveredpeople of the high office, symbol ofreverence and honour. •BCSftKVISITBOOKWISEin Commissioner Street(Shakespeare House)8347206/7/8for their wide rangeof African Literatureincluding allRavan Press publications.6 STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 198

PoetryThabo Mooke, Kedisaletse Mashishi, Bika, Leonard Koza.NOWHERE TO HIDEGirl wake up,The morning sun has caught us napping.We came out here, sneaking to this place last nightTo quench our desires — and it was wrong, we bothknew.He was out of town, you said,Visiting his old folks down in Giyane.We could not go to your home'Cause the curious eyes of your neighbourhood wouldspy on us,Neither could we go sneaking into my bungalow:Jabu, Ntombi, Sipho and Zodwa would see us.It is wrong, they all know.Wake up girl,The little birds are singing up in the trees,The morning sun has caught us nappingAnd we have nowhere to hide.The world is waiting outside.Thabo MookeMALARIA FEVERMosquitosStingingHelicoptersUsingExpensiveFuelMyBloodHelicoptersGunDownA TenYearAtMeadowlandsYou chose not to believeI stingWhen I told you I willStingBikaINFERNOPlease clarify to meAm I not seeing miraclesWhat is all this aboutThe sophisticated highly strung babiesWe the youth of this generationCan set a volcano aflameWhere are those innocent daysof clay oxen and mud housesThe days of waltzing in rainPlaying games with trainsCould someone please help usAre we not confused, misledBlind wanderers without destinationWe the generation of nuclear bombsKnow all beyond the sunAs if in control of the worldEverything impossible for usReally this is heartbreakingMust you be innocent bystandersTo witness us so confusedWe, the irresponsible future leadersAs if we are intelligent enoughGuide us to righteousnessTake us back to our AfricaAway from BotsotsosBack to our traditionAway from skyscrapersFar from temptationsDetentionsVolcanoes of the northUnsteady moody climate of the southBack to our AfricaDivorce not your traditionSell not your black soulCling to yourselfBe yourselfAccept changes wiselyKedisaletse MashishiINITIATIONThe barrel of responsibility is pointing at usLet us go to the mountainAnd sit down in bandsSinging of war and loveApartheidWe will come back equal to youTo stone youA stone for each reincarnationYou will never everBreathe againLet us go to the bushBikaUNDER THE BRIDGESandwiched between camouflagingroad bushes.Radio glued to ears.Eyes magnetically stuck on unawareroaring engines passing.He reads for trespassing traffic.Book in hand he stops the overloadedon the separate route to location.Unlicensed pilot ticketed,half-a-dozen migrants martially offloadedto walk to Langa Township.Walk to a portable homehalf perched in Transkei —A home swinging like a nest on a branch.A home exposed to raids by cruel men and weather.A home so temporarythat with a drop of inkit can be drowned in exile.A home where father has been cultivatedby white prerogatives into wild fruitemerging only at season time.Leonard Koza^TAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981

He woke to a day without promises,without hope, what could be called ...A NORMAL DAYA STORY BY KENNY T. HURTZHe woke to a day that would havebeen better left unseen. The weatherwas bright and hot, the air still, the time11:37 by the digital clock, that excellentmachine that woke you with ashrill ring, or with soft music if desired.Or didn't wake you at all, if such wasyour choice, but left you to growslowly conscious without persuasion,sick with sleep, eyes gummed andbreath foul. And the clock, if not soinstructed, would also make no fuss ifyou never woke again at all, would humuntil its mechanism wore with age, orthe electricity was cut off. Really, theunderstanding of the simple machinewas amazing.He woke also to a day without promise,without hope, what could becalled a normal day, normal indeed, formost. The movements could be preciselyplotted: Wake, dress, eat; go to work,work, eat; work some more; then gohome, eat; and in the evening thedesperate search for distraction wouldfill the hours before sleep, and the cyclewould begin afresh the next day. Thisrepeated from birth to death, withminor variations, for most. And menspent all their time bound into thecircle, and that was called life. Formost.The blankets had become disarrayedin the night, which was unusual, he didnot as a rule sleep violently, and mostmornings found the bed as neat as whenit had been gratefully entered the previousnight. Perhaps a nightmare? But heremembered nothing, and he felt rested,as if his sleep had been sound and still.Yet maybe it was not so, for whoremembers the morning after, theterrors of the previous night? A movementof his legs sent the blankets, sheetsand everything else sighing to the carpet.He sat up, now noticing that he hada violent headache, situated, so it felt, inthe centre of his brain, a pinpoint focusof pain that pulsed quietly and rhythmically.He could hear, distantly beyondthe muffling curtains, the insanetwittering of mossies, what he believedwere called Cape sparrows, this item ofuseless information having remainedwith him in spite of all; and why Cape,he was nowhere near the Cape? Withoutopening the curtains he stood up andslipped on a robe, the sole aim in hismind being the seeking out and findingof the morning newspaper with its dailycrossword puzzle, which he normallyattempted over his first cup of coffee,and sometimes his second, although bythen his room had normally been madeup and he would return to its comfort,its calming neatness.' ... To clean it up! She refused! Ican't. . . ' The voice trained off as heentered the bathroom, so painfullysterile, and closed the door. Hismother's voice, strident and excited.Now what, he wondered. Had therebeen a fight, had some trivial crisisoccurred? What the hell . . . the thingssome people find to occupy their time,it was pathetic. As far as he was concerned,the public raising of a voicecould be considered positively indecent.After all (he thought sarcastically) whatwould the girl (she was about twentyfive,as near as he could guess) think?She had certainly been rather withdrawnsince she had joined them somemonths ago, she went about her workwith what appeared to be suppressedmelancholy. Her name was Rosina,though Rosina who was anybody'sguess. They were all called Rosina, thator Mary, it suddenly occurred to him.The high incidence of these names intheir community must be beyondcoincidence, or perhaps they weresimply pseudonyms chosen to beappealing to white employers. And shecan't do anything, his mother had toldhim once, she doesn't even cook! Sowhat, nor did he . . .He swallowed four aspirins withoutrecourse to water. The toothpaste wasfinished.He scowled at the crumpledtube for a moment, as if to discover thereason, as if it could tell him. Halfheartedlyhe splashed water in his face,throwing most of it over his shoulder,dripping on the polished floor as hegroped for a towel. Couldn't cook! Justimagine! The headache, locked in conflictwith the aspirin, quickened itsrhythm. ' . . . expect me to do it?' saidthe voice as he stumbled from the bathroomwith thoughts of hot coffee, andthat too would have to be delayed, ifthe jar was not empty as well, until hehad secured the paper and checked thathis brother had not beaten him to thecrossword, which sometimes happenedand left his remaining day with a tint,albeit subtle, of incompleteness.Somewhere in the house a doorslammed. The cat on the landing regardedhim with silent amusement. ''Hello, Jean, how've you been?' he saidin a pitched falsetto, one part of hismind recoiling under the absurdity, anotherexulting in the sheer idiocy of thegreeting. The cat broadened its smile,but otherwise ignored him.In his mother's room she was inexplicablyabsent. He found the paper,the crossword half done, the scrawl belongingto his brother. The price onepays for sleeping late! He decided itdidn't matter, scarcely convincing hirrself.'Hi,' said his mother, coming into the |room, And then almost as an afterthought,'I've dismissed Rosina.' She satdown on the bed. Beyond the glass therooftops gleamed in the sun, red, pink,grey. He could make out a garish bussliding from its terminus and slippinginto the angry stream. The cat glidedthrough the door and flopped to thefloor at his feet, rolling over onto herback. He stretched a foot to her. 'Hi,' hesaid, wondering at the suppleness of thecat, 'what happened?''I asked her to clean the dog's messin the kitchen. It was my fault, ]suppose, I fed them late, but do youknow what she said?' He confirmed thathe did not. Still gazing out of the windowas though it might have killed himto move, he saw three birds bank togetherand land smoothly, one after another,in a tree of repulsive aspect in thenext garden.'She said, "I don't clean the dogmess." ' Perhaps his mother expectedconcordant outrage, but when none wasforthcoming she added 'The cheek!'He turned the page, reflecting: Whowould make his bed today? and more,so she was gone, well, she had not beermuch good anyway, her loss would beeasily enough tolerated. KILLERSTORMS BATTERED HOUSES, readheadline. What, he wondered was a killerdoing storming battered houses? Thewhole idea seemed preposterous. Hecould scarcely believe it. Perhaps theymeant that killer storm had batteredpreviously unbattered houses, housesthat were as neat and trim as his ownbefore this battering took place. He feltthat the effort needed to clear hproblem up would have to be tremendous.He threw the newspaper at thecat, who stalked off indignantly. I hatemaking beds, he thought, what a bloody8 STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981

mess. His mind clouded for a moment:What did it all have to do with himanyway? But he could feel that it did, ina manner as yet unclear, one that wouldshortly unfold to the form of its finalconsequence. 'So I told her she couldleave,' said his mother, her tone slightlyexasperated. He began to sweat lightlyand shifted uncomfortably. His mothercontinued ' . . . but I owe her threeeks pay, and she still has the twooveralls I bought for her.' She took aplain envelope from the shelf behind heri handed it to him without a word,n turned and left the room. The cat: ted the window sill in one smoothtion, and settled down on its sto-, ch.He * picked up the paper and tried toconcentrate. If that's seven down theneleven across must start with a j, andt mty-two with an s. It still made nos ise. The envelope he had stuffed intoh pocket, and now he took it out andc nted the money. Dirty work again,s ; cifically made for him, as usual.I tered houses, battered houses. Whatg lewspaper. What a world! The dayhad taken on an unpleasant metallictang, everything was too hard, toot rtle, as though the slightest wrongmove would cause the entire future tos cter irreparably. The thought of movi:appalled him, as did the thought ofg ng back to bed. He felt hopelesslys dwiched between two equally unpasant alternatives. He threw ther ^spaper down again in despair and,v h a violent effort, made his way toi kitchen.There the too-clean fittings gleamed! ^fully, throwing the shards of theirJ ections about the room wantonly,t scene again one of oppressiveI ghtness and order. What would shec he wondered as he filled the gleam-photo, Biddy Crewei kettle, what would he, for thatmatter, do in the same position? Evictedc a moment's notice, if this really waseviction. Yes it was. But why had shebeen so sullen, he asked the rising steamand, now that he thought of it, why hadnever spoken to him without he firstspeaking to her, and why then had heri ponse always been flat, spoken in thevoice of one fatalistically resigned to anawful, irrevocable fate? God! But perhapsthat was going too far, after all,what did she have to complain about?r lot was not too bad, it certainly< ald've been worse. She had her ownroom, food, clothing supplied, and lightwork to fill the daytime hours constructively,and the nights were her own, pluswhat amounted to plenty of free time.1fist, she even got paid for it! Funnilycough her situation was not so differentfrom his own, he too had a roomand food, and from the same people,a 1 the difference was this, that hereceived no payment for the work hedid around the house, the small tasksthat were all he seemed fit for since hisrapid decline of a few months ago. Yes,upon final reflection what exactly washer problem? He himself would gladlyhave done what she refused to do,without even a thought of payment. Hefought down a rising feeling of selfrighteousness.After all, what exactlydid she expect? And even . . .A key sounded in the door and thegirl came in quickly, shutting the doorbehind her, dressed no longer in heroveralls but now in a smart skirt andblouse, red and yellow respectively, andhigh-heeled black shoes of delicate design.She turned hurriedly from thedoor and saw him standing at the cupboard,frozen in the act of reaching fora cup. The expression on her face didnot change, but as their eyes met, thesmartly dressed woman dissolved andthe attitude of urgency faded completely.Far away the barking of manydogs could be heard, the very hounds ofhell themselves perhaps. She droppedher eyes instantly and her postureslumped slightly. Then she turned to thedoor and was silently gone, the sound ofthe latch locking before he quiterealised what was happening.For some reason he felt offended,even hurt that this had happened. Andfor some reason even less clear thekitchen suddenly seemed intolerable, asthough it were an area that had beenhurriedly evacuated after contaminationby some malignant entity. He sensedthat he was being absurd, over-sentitiveat best, but why did he feel that it mustbe he who was the malignance, and thatit was due to him that the room nowheld an air of blighted desolation?The coffee he sipped on his way upthe stairs was too hot, far too hot, andSTAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981 9

made by one who did things with suchmaniacal precision that there was noroom for error. And when he enteredhis bedroom, the sight of the naked,rumpled bed and the caliginous illuminationshocked him once more. Why didit look so unbearably squalid, so nauseating?He threw the curtains asunder ina frenzy, the coffee forgotten, anddressed rapidly, jeans, shirt, sandals.Outside, as if by deliberate contrast,everything was razor-sharp, the blue ofthe sky was so blue that it scarcelyseemed real, the green of the small suburbanlawn blasted forth with almosttangible force, the house, glaring whitein the sunlight, was actually painful tolook at. The vividness of these impressionsbattered his senses brutally. Hehad stumbled, almost fallen down thestairs on his way here, and now heglanced back into the gloom of the opendoorway, hoping perhaps for thestrength to go back inside and forgetabout all this that he had suddenlycome to. The headache thundered androared inside him and he felt close tofainting, indeed he stretched out hishand and leaned against the wall, hisbreath rough and quick. After a momenthe pulled himself together withwhat he considered a heroic effort, andwalked in the direction of the servants'quarters, what had been called 'theback' for as long as he could remember.'The back' was situated behind thegarage, and a sort of alley led down tothe three small rooms that the domesticscalled home. Home, he thought, foras long as it lasted, and who can reallybe held responsible for the incontinenceof the family dog? Or was that anexcuse? A vine had been allowed togrow unchecked along the right boundaryof the narrow passage in which henow found himself, and choked offmost of the little walking space. Abovehis head it curled wildly, as if in delightat its own freedom, completely engulfingwhat formed the boundary to theneighbours' own 'back'.Turning left at the end of the alleyhe met a scene of such astounding uglinessthat he physically recoiled: thesame vine, pompous and tyrannical,covered almost everything in sight; itsleaves, sickly green in the bright sunlight,had infested all but the mostfrequently used areas in the tiny courtyard,growing like a gangrenous slimeover the small, disused coal-pit (sincetheirs had become a smokeless zoneelectric water heating had been installed),through discarded pieces of pipingand lumber and the rotted skeletonof an old water tank, and emerging inrampant triumph through an enormousand inscrutable tangle of metal that layat the far end of the space, against acrumbling brick wall. From one end ofthe yard to the other stretched a destroyedwashing line, one of its originalfour strands miraculously intact, the uprightsdeviating ridiculously from theperpendicular (and even here the hideousvine scaled upward to the sun).Brickwork showed where patches ofplaster had fallen from the walls to theground, which seemed in compositionto be a sea of mud, where it was visibleat all, and pools of dirty water reflectedthe sky with mirror-like competence.The smell hit him simultaneously, a sourmixture of humanity and wet coal andsomething else that he could not identify.The walls of the building that stoodon his left were streaked with dirt andthe gutters above hung sadly from theirmountings, their once-yellow paint flakingin obscene curls. None of thewindows were broken; this amazed himfor a moment.And then, from one of the threedoorways that opened onto this awfulyard, the girl emerged, and he was againstruck by her neatness, which seemedabsurdly out of place here. He wonderedwhether she would disappear again,but no, she stood on the thresholdwithout moving.'Rosina —' he took a step forward,narrowly avoiding a large puddle. Shelooked at him with the same emptyexpression that he remembered, anexpression that could have belongedequally to one either profoundlyshocked or extremely bored. ' . . . Themadam wants her keys and overalls,please.' He wanted to say 'I'm sorry',but he didn't. The words had becomestuck somewhere. His voice soundeddisembodied, as though someone behindhim had spoken, and he had afleeting impression that the entire buildingwas somehow shifting.The woman pointed, without speaking,into the room, where two neatlyfolded overalls lay on the truly nakedbed, it had not even a mattress. Apartfrom this and two small packing boxes,the room was bare. She handed him asmall keyring (Enrolls Datsun, Phone23-4965) with three keys, then turnedand dragged the boxes from the dimroom. When she had done this sheclosed the door and the Yale lockclicked shut. He began to feel intenselyuncomfortable, as though it were hewho was at fault, as though it were behindhim that the door had closed, forthe last time.'The madam owes you some money,'he said stupidly. He couldn't understandwhat he was doing there anymore.'Yes,' she said. He saw the sadness inher eyes as she glanced up.'Do you know how much?' he asked.'No.''Here.' He thrust the envelope at herand she timidly took it and pocketed itwithout counting, standing small andalone before him, eyes downcast. A feelingof immense sadness suddenly seizedhim, constricting his throat and flingingto the winds the logic that had helpedhim endure all up to now. The girl hadseen the inside of that room for the lasttime, and the pathos of the scene wasnow stamped with an awful seal of finality.And still she stood there, as thoughawaiting his permission to move, tothink, to live.At once he felt the desire to run, toget away, far away, anywhere. A faintbuzzing began in his ears. No, it was anaeroplane, a distant silver speck. Heturned on his heel and walked offswiftly, through the tangled passage andinto the house, his house, his for as longas he desired.From his bedroom window helooked down and saw a small figure,laden with two boxes, her entire worldlypossessions, dragging her way up thedrive towards the street where, as far ashe could see only emptiness awaitedher. He watched her slow encumberedwalk to the gates, the final boundaries,with a feeling of immense desolationand almost anguish. The whole affairseemed to him dreadful and unnecessary,and what had been gained anyway?And what lost. . . ? And then,with a final backward glance, she wasgone, not only from the house and hissight but also from the consciousness ofthose who could do without her, whowanted no part of her, those for whomlife went on with barely a skip in thecontinuity.He gazed from the window long aftershe had gone, seeing nothing, thenturned back to the room. The unmadebed awaited him, and the cat now snuggledinto the disarray of last night'ssheets. Faintly now, far away (or was itafter all in his head?) he heard the wildbarking of a thousand dogs. •10 STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981

'My Dear Madam...by Nokugcina SigwiliThe full text of this story will be publishednext year in 'Reconstruction', edited by• thobi Mutloatse.On 24 February <strong>1980</strong> I was employedas a domestic servant. I had totart work at 7.30 a.m. which meantt I had to wake up at 5 a.m. everyday to catch the bus. We agreed that Iuld work a five day week. My madamwas an English woman who lived in amall house by herself. Her childrenwere in England and she was divorcedfrom her husband. She sounded veryexcited about having me as her servant.I ould see this because she was consitly on the phone, telling her friendsabout her 'new girl'. She told them:Phis one is exceptional because she canspeak English without any problems andshe is very clean and moreover, polite!'Within a week I had met most of herf -nds because they could not resist thetemptation to come and see this exceptional'new girl'. Of course I could notb me them: my madam was rathere iggerating things. All the same I didnot want to disappoint her by misbehaving.I was very polite and each time herf! nds came in I would quickly askthem if they would like tea or coffee— before she could get a chance to doso, As I had expected, this won meappreciation from her friends.The first two weeks with my madamwere very happy ones. We were alwaystalking about this and that in the world,about our likes and dislikes. Sometimessi would tell me about her previousgirls, who could not behave themselves.'What did they do?' I asked.'They would steal my clothes, mymoney and even pinch my powderedsoap.''Mh, that was bad of them.''Yes, yes, that's true. I remember onegirl stole my bra, a memento from onefriend of mine.'I said, 'She must have been a fat girlthat one,' and she replied: 'Yes she wasand very cheeky too.'I could not help liking her because' was somewhat childish, but ourfriendship did not last long.The thing started one day when I wasking coffee for two of her menfriends. My madam came in and told methat I should call those two guys 'Baas'!I was caught off guard this time.'What! You must be joking!' Thesewords escaped my lips before I couldthink of preserving my 'title'. I wassimply baffled.What now, my dear madam was at aloss for words. She simply frowned atme. It was hard to believe that thesewords had come from her exceptionallygood girl who always said: 'Yes Madam.'These guys I had to call 'Baas' weremore or less my own age and they startedlaughing, asking her why I had to callthem 'Baas' instead of using their ownnames. My madam decided we shoulddrop the subject there.When everybody was gone and wewere left alone she sent me to a hardwarenearby to buy some Bostik for hershoes. I was not served when my turncame.'Can I have Bostik glue, please!' Isaid this several times without anyattention being paid to me. 'Bostikplease.''I want a big broom to sweep outside,have you got one?' one lady said,and she was served immediately. Theymade it a point that every white wasserved before they half-heartedly askedme: 'What do you want?''Bostik,' I said.'What for?' he asked — as if he didnot know.'For shoes.' I was annoyed at such aquestion. This was after a long time ofimpatient waiting.When I got back I told my madamthat I would appreciate it if she went tothat hardware herself if she wanted anything.'I think they will serve you quickly,'I went on.'Why?' she asked.'You are white and it is one of therules of that hardware to serve whitesfirst, no matter who came first,' I explained.'Who said that?' she wanted to know.'Their reaction did.''You must forget that you are blackand life will not be so difficult.' She saidthis smiling and went on before I couldeven say anything: 'Maybe the way outis to call them "Baas".'This word again! Things were turningsour for me. This word was becoming anightmare or rather a 'daymare' becausethis all happened during the day.'I am very sorry if that is the case,because I never call anybody "Baas"whether he is white, red or yellow.''I am warning you about your behaviour,my girl. You must be carefulabout what you are saying, I am tellingyou. South Africa is not a very lovelycountry for a black person if you do notlearn to be respectful.'I did not ask her what respect meantbut I was soon to find out.Do you know what happened thefollowing morning? A handful of herfriends came round to talk to me!'About what?' I wanted to know andthe answer I got was, 'Just about life ingeneral.'I felt honoured. I was about to sitand talk to the 'witmense' about life ingeneral!'How old are you?' One good lookingand tall lady started the talk about lifein general.'I am twenty-one.''Where do you stay?' Walk-Tall wenton.'In Alexandra,' I said.'Do you like it there?' This camefrom one stout guy with a beard; theSTAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981 11

hair on his head was shiny black and sowas his beard, except that it was bushy.'Yes, I do like it there,' I said.'How do you find your madam?'Mr Black Beard went on.'I think she is kind,' I said.(At that moment my madam wasvisiting the loo.)'And she thinks you are a good girl,'he smiled.'I'm glad.' I sort of blushed. I wasnot very sure where this interrogationwas leading.'She tells me you are interested injournalism,' an elderly lady said smiling.'That's true.' I smiled too, not becauseI felt like smiling but becauseeveryone in the lounge wore a smile.'How would you feel if you couldbecome a famous journalist?' she wenton.'I don't know.'This called for a good laugh fromeveryone in the house. Some had to drytheir eyes, which were laughing too.Walk-tall was the first to recover becauseshe did not laugh much. Apparentlyshe was the kind of person whowould like to keep her teeth inside if itwere not for her upper lip that wasshort and acted against her. She wascollected and her face was expressionlesswhen she asked me this question:'How do you feel about politics?'My! The change in the talk about lifein general was noticeable, to me inparticular . . .'Where were you during the 1976students' riot?''Would you rather the blacks ruledthis country?'What a lot of questions! I did notknow which one to consider first, so Idecided, 'I do not know much aboutpolitics,' was the right answer.Then Granny said, 'Do you knowanything about the Azapo?''I know the name of the organisationand that's all,' I replied. I was notpleased at all. We were not talking freely.I was being interrogated and thatmade me feel bad, because I was notvery sure about how to tackle this and Iwas getting restless.'What do you think of Mugabe?'came another bullet from Black Beard.This put everybody on the alert, searchingfor something in my face.'I do not understand' — and I meantjust that.'I mean, do you think he is suitablefor his position?' explained Black Beard,but I was more surprised than before.'Yes, do you think otherwise?'Granny had something to say beforehe could answer me: 'I think he is goingto make people starve to death! All hewants to do is get rich, famous andhappy with his family.' She said thiswith her chin high in the air.One man, who had been quiet allalong, had something to say too: 'Heenjoys sitting down and talking nonsenseon the television.' He wore amocking smile on his face.'Making many promises he will neverfulfill,' Black Beard put in.'Black South Africans think he isgreat,' said Walk-tall, and they all burstout laughing.'You people are still going to suffer.'This one was directed at me by Granny,who went on to say. 'People who wantto help you, people who understand thesituation in this country, you call "sellouts".''Yes, this is strange,' said Walk-Tall.'These words "sell-out" and "puppet"are in the air and they are directed atthe wrong people.''You never know how these peoplesee things,' added Black Beard.My madam had been very quiet, shehad been nodding her head in agreementand laughing. Now she decided to saysomething: 'It is not a matter of seeingthings, they are just narrow-minded . . .'Up to now they had been talkingamong themselves, not to me, but I hada question and so I voiced it: 'Who arethese people who are wrongly calledsell-outs and puppets?'I was answered almost immediatelyby Walk-Tall: 'Gatsha Buthelezi, Matanzima. . . 'My madam felt she had not finishedand so she helped her: 'Mangope.''Sebe.' So the quiet guy had a namein mind too. 'I do not know muchabout Mphephu, but he is not a bad guyeither,' he said. 'Do you also think theyare "sell-outs"?'Before I could say anything, BlackBeard came to my aid: 'That is obvious,all girls of her age think so.'But I still had something to say: 'Ihappen to have lived in the Transkeiwhich means that I know more aboutthe conditions there than you do.''We do not have to stay there toknow how happy people are there.'That was my madam.'It is so unfortunate for Matanzima,who does his best just for them, thatthey do not see things his way,' saidWalk-Tall. 'It is always the case, theblack people do not know who theirtrue leaders are.''Because they are narrow-minded,their minds are just like this,' said mymadam, using her forefingers to showhow narrow our minds are. 'All theywant is communism!' she went on.'That's one thing I hate!' Granny saidnervously.'I don't care what they do withthemselves. The moment they bringcommunists into this country we won'thave the smallest worry. We'll just flyback to Europe,' the quiet man said andI could see that he really did not care.Walk-Tall felt he had not finished hisspeech and she did the job for him: 'Wewill leave them crying for our returnjust like the people in Mozambique.''They are too narrow-minded to seethat — just bloody stupid,' my madamagreed.'These people do not know how tolive in the first place,' Granny retortedand this made me feel kind of mischievousso I said, 'Maybe they will knowhow to live in the second place.'Some were amused and some wereannoyed at such a foolish comment.'This girl of yours couldn't live in Irelandnor in Switzerland.''She could not afford to go thereanyway.'I sat there looking from speaker tospeaker and smiling from time to time. Iwas not given a chance to say anythingand so I just pushed my speech in anywherewhen I felt like it.'How are things up there?' I askedBlack Beard.'In Ireland? Dear God! Things arejust fine there ... I mean everybodyrespects each other. People are kind andsensible. It's not like this mad country.''That's true, people are mad in thiscountry, I'm telling you.' That wasGranny. 'I remember at my home, wewould leave the windows wide open andno one would come in to steal ourthings,' she went on.And this made my madam remembersomething too.'That's true, look at what Tshaka andother fools like him did to the people.''That's true, look at what Hitler andother fools like him did to the people.' Isimply had to say this, even if my opinionwas not asked for. The effect wastremendous.'This girl is mad. By God she is!' thequiet guy shouted, standing up and sittingdown again almost immediately.He was not the quiet guy anymore. Ilater learned that he was German.'I'm sorry, I did not mean to bemad.' I had to make my apologies;seeing the cloudy expression on his face.'My dear girl, if I were you I wouldthank God that I had lovely clothes likethese and a necklace like the one youhave on.'(My madam had no overall for me soI was working in my own clothes).'Her belly is full and there is a roofover her head, that's all that counts,'Granny said, and Black Beard felt that Ididn't know life yet — that I had neversuffered.'Yes, she cannot believe it when Isay I came from a very poor family. Iremember once when we lived on potatoesday in and day out for a wholeContinued on page 1412 STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981

Poor Business for the ArtistBy Nangirayi MajoTembo sat down beside his visitor who was going throughhis pictures with a surprised look.'I didn't expect you to succeed to this extent. Is there awhite behind this?' Godfrey asked, tapping on one of thepictures. 'You should be getting somewhere at least.'Tembo snorted, 'This is this country and you don't getanywhere.''Why?' Godfrey was surprised. 'You have got your brushesand paint — and loads of talent. What else do you want?'Tembo did not answer. He went to a chest of drawers andbrought back some copper engravings which he laid out onthe table.'These are fantastic! Did you do these too?' Godfrey waswide eyed.Tembo did not answer him. He felt a little sorry for hisfriend. He thought him a little too naive — or pitifully misinformed.Godfrey had just come back home from six years'exile overseas.'I told you nothing has changed,' Tembo tried to explainto him, knowing it was useless. 'Don't take in everything thepapers tell you.''Come on. You must be making loads of money with thiskind of work.' Godfrey thought Tembo was unforgivablybelittling his own talent. 'How much is this one?''That's an order the boss gave me to do this weekend.Some rich tourist wants it on Wednesday. I'll probably get$60 commission on it.''You must be joking! How much are they paying you permonth?'Tembo thought of going into detail, to give his friend thetrue picture, but how could he do it to someone who hadcome back full of hopes about the changes for the better thathe had read about miles and miles away from home, dreamingof dovi and sadza? How could he explain to him thatmost of the time he had not even a cent in his pocket? Thathe didn't even have a savings account? The little he earned hespent on beer. That was his only source of happiness, he toldhimself, and as for the material things — he would just forgetthat.'Thirty dollars per week is what's mine,' he-finally said.'For -this, this - ?''I can't force you to believe me.'Godfrey looked at his friend for some time, his head in hishands, then he straightened up and said, 'Look, why don'tyou drop the job and do your own thing? I see no reasonwhy you should work yourself to pieces for somebody else'sbelly.''Give me the money and the market,' Tembo said sarcastically.Godfrey seemed to digest this. He was beginning to understand.He said, 'But there are some blacks who are living inquite a style. Where do they get the money from? They can'tbe all that fortunate if what you are saying is true.''In hard times like these people become prostitutes.''Come on — they can't all be crooks.'Tembo looked at Godfrey sadly. 'You have been away along time. I can't even begin to tell you how many thingshave taken place.''Things like what?''There are more slums now than when you left.''But there are also rich blacks living in once-white-onlyhouses. Have you tried selling your work to them?''And listen to them telling me to find a better job? Somedon't even know how to look at a picture. Money is for living— property and big names, not art.'Godfrey looked at his friend gravely. When he spoke hisvoice was low. 'There are many people I know — acquaintances,schoolmates — influential people who really thinkyour work is great. They tell me the only trouble with you ispride. I hear that you have even turned down some ordersthey gave you.''Lies,' Tembo said weakly.He stood up and went to the window. What Godfrey hadsaid was partly true. There were some patronising blacks whohad approached him for portraits or other such sentimentalthings and he had told them he had no time. How could hetell Godfrey that what these people wanted wasn't his paintingsbut big names for themselves? Something to show off totheir white friends over Sunday teas and sundowners? Theywere afraid to be embarrassed by their white friends whoreally knew what art was all about. Wasn't it strange thatthose blacks who now praised him for his work had beenintroduced to it by some whites who lived miles and worldsaway from them?However badly he needed money, Tembo felt he hadsome rights to his own self. He would do what he wanted inhis own way. He knew they knew he was great and he woulddo his best to keep them aware of it. It gave him a beautifulfeeling inside, although most of the time he felt bad whenless artistic friends of his exchanged their works for Mustangs,Alfa Romeos, Datsuns and posh houses in the suburbs.Even those he had taught to put brush to canvas simply tookwhat they wanted from him, learned a few tricks, sold two orthree portraits of some big politician, then bought a car and aTV set, became screaming successes overnight — and left him.He liked it least when he felt like a cheap, fraudulentfame-monger, blaming his failure on the situation of thecountry, stealing little artefacts behind his boss's back andselling them in the beerhalls and the streets for a mug ofbeer. And he would feel even worse when all the beer hadbeen drunk and he would start telling his drunken friendswhat a great artist he was.'And I know another great weakness of yours.' Godfreystood beside him at the window. He didn't wait for Temboto ask him what he meant. 'Drink. Nothing comes to anyoneon a platter and I might as well tell you right now, as afriend, that if you don't pull yourself together, do somehonest work and stop feeling all-important, self-pitying andignored, you might yet do something people will rememberyou by.'Tembo didn't answer.'Look, Tembo. Do me a favour. Just let me have one ortwo of your paintings. I have some friends overseas whomight be interested to know that you exist.'Tembo took a long time to answer. When he did, he wasstill looking out of the window. 'They won't sell.''Never mind whether they will sell or not. Just leave thatto me.' Godfrey was quiet for some time. 'Will you do thatfor me?''If you insist.''Good.When Godfrey left, Tembo thought about a painting hewas doing. It had taken him over a month now but hecouldn't get it right. He looked at it for a long time. Hewanted it to carry a lot of things, this face of his grandmother;all the things that he had felt and she had felt and allthose people who mattered to him had felt. But he couldn'tSTAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981 13

get it right; it eluded him. He forced hismind back to the painting each time hefound it, drinking a bottle of kachasuor undressing a woman or telling somevote-monger for some political party togo to hell. He gritted his teeth andbrought it back when he found it,wandering in some overseas citieshe didn't know, telling the native whitesthat he didn't need their help whilewishing they would buy up all hispaintings.All through the remaining hours ofthat afternoon until duskfall he foughthard to clear the crowds off the avenuesof his mind, trying hard to leave itdeserted, empty, so that whateverwould finally come would not be of hisown making. It was hard, but when hewent to bed at eight, after turning thepainting to the wall, he knew it was halfcomplete and the tears that filled hiseyes were not for anything that hedesired in life nor of anything that heregretted. •DearMadamContinued from page 12mon the one hand, or sloganizing on heother.IA STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY l? 81

<strong>Staffrider</strong> Gallery Goodman Mabote,Shadrack HIaleleGoodman Mabote, Untitled, DrawingShadrack HIalele, Untitled, Lino-cutSTAFFRIDER, DECKMKiiR <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981 15

<strong>Staffrider</strong> Gallery Mphathi Gocini, Radinyeka MosakaIRadinyeka Mosaka, 'Dancing Starvation Away', DrawingMphathi Gocini, 'African Wedding', Lino-cut16 STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981

D.John Simon.IN MEMORIAM-BERNARD FORTUINSHOOT TO KILL(In memoriam Bernard Fortuin - 28 May <strong>1980</strong>)They killed you, poor boy,Before you could speak,Gunned you downWould not listenBefore they firedAnd left you to sink.No aid allowed, poor boy,No aid allowed,Instead loud curses in taalFor a mother's soft armsTo give you rest.Paul Sibisi, 'Unrest IF (colour)SOUTH AFRICAN PARALLELSqueezing the trigger, cold goldeases through the lobeand dangles like a tearimpaled on a young cheek.The ears are puncturedfor the sake of vanity.In Elsies River, where windsheap Cape dust on dustin desolate places,two mothers had their childrenpierced, in the nameof peace and sanity.Shari RobinsonBALLAD OF BERNARD FORTUINElsie's River in the afternoon:Kids throwing stones, car windows splinterIn Halt Road, where the mob grows,Lame and blind governors, cause of the fury,Sit, eating beefsteak in Parliament House,While cold sunlight strikes on the hard stones —Clenched hard, hate-hard, white hate . . .Bernard Fortuin, sent to buy bread;His mother waits, and waits;And jungle green, brown outfits of policemen,Brown to be inconspicuous — in Elsie's River . . .A Blue Kombi receives the onslaught,Black stones batter its body;It spits deathAnd Bernard Fortuin receives the poison . . .Crowd kept back — blood liquid from his throat'Laat die donner Vrek,' says a cop.Mother waits for the son and the bread,And the snake recoils,Waits for the nextBernard Fortuin.Steve JacobsThey killed you, poor boy,Before you could shout,Gunned you downWould not hearBefore their fireTook you for night.No aid allowed, poor boy.For those felledLike trees,Instead loud curses in taalFor a mother's grief.They killed you, poor boy,Before you could speak,Before you could shout,Before you could scream.They blew your lifeAnd cursed in taal.To what end,Fifteen years old,Have you been spent?To what endHas your being gone,From us been sent?To what endHas your blood been spilt?To what endIs buried a nation's guilt?A mother's tears,A people's grief,A nation's conscience:We lay flowersThis June dayBreak petalsAnd wonderWhy things are soBeneath our sun,Forever changed,Poor boy,By you.D. John Simon(Written 31 May <strong>1980</strong>, 'Republic'Day,Lansdowne, Cape Town)STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981 17

Staff rider ProfileCharles MungoshiZimbabwe WritersTwo interviews by Jaki SerokeArmed struggle in Zimbabwe began in 1966. The climate of repressionduring the next fourteen years did not encourage the growth of theliterary arts. In that period some writers succumbed to censorship,others took the road of direct political involvement. There were alsothose who persevered and continued to write.On a recent trip to Zimbabwe we discussed the writers' struggle with twoZimbabweans, and also with research workers at the National Universitywho are concentrating on the history and continuity of Southern Africanwriting. Throughout our discussions the emphasis was on the solidarityof writers working in the Southern cone of the continent.^We were brought up inA Literary Desert"We grew up in a literary desert. There was not much to readabout ourselves, historically speaking, and everything weclung to was from 'down south'. We read writers like ThomasMokopu Mofolo, Ezekiel Mphahlele, Alex La Guma and soon at the time when we were at high school. These were thewriters who communicated best with us. At this stage, by theway, I performed very poorly in my formal scholarlyendeavours.I took an interest in writing, putting out a few poems hereand there. Writing soon overtook my studies. Lookingaround at my school-mates, I saw that no-one was satisfiedwith conventional reading which did not really relate to ourimmediate experience.I knew little about Zimbabwean literature until I cameacross Ndabaningi Sithole's The Polygamist. He had alsowritten African Nationalism. Lawrence Vambe had writtenAn Ill-fated People. These books were factual and could notbe measured in the creative sphere. The censors banned themat first sight. I grew worried, because at that stage one couldnot single out one novel proper by a Zimbabwean which wasenjoyable.There is a tendency among many young writers to fall forpoetry. Apparently they think it is easier. Until OrdinaryLevel at school, poetry is taken very naively. The things thatcome out of this naive source are not really poetry as such.It is a bit hard to say what Zimbabwe literature will belike now that we are independent. After so much human lossand suffering, we are most probably facing the theme ofreconstruction. The damage done to human minds has to betaken care of.I think that writing, at any time and in any place, shouldlook into the problems a society is facing. It should dig downinto other people's private affairs — trying to find the meaningof our communal experiences.We have come to realise that any writing in time of war isaffected by the confusion of such a situation. Our writingscarry within themselves a certain related feeling. There is atendency to try and play down what you are putting across.Charles Mungoshi is based in Harare. His novelWaiting for the Rain (Heinemann's African WritersSeries) won the 1976 Rhodesian PEN Prize and hisShona play has recently been published in Salisbury.He is currently employed on the editorialstaff of the Literature Bureau.Most of the time you feel you haven't really come out withwhat's happening.We never had a creative magazine in which we could pourout our feelings. Most commercial magazines were terriblyretrogressive: accepting only 'love' stories. So, our workswere stifled in a way. Most of us rejected the temptation towrite such things. For honesty's sake, you had to write and'snug' your manuscript away safely somewhere.Not until towards the end of last year when ZimbabweArtists and Writers Association was formed did writers cometogether. Under the old government it was difficult to grouptogether as artists. Unfortunately ZAWA disintegrated afterit was formed. As was the norm, those who held office werenot even writers.In this country there has been a kind of complacencyamong black artists. It has been really difficult to come togetheras artists. I think this is one of the reasons why mostwriters resorted to a political platform pure and simple.In 1969 we formed a Drama Society which I chaired forthree years. The problems we faced then are still aroundtoday. We worked with frustrated school-leavers who werestarry-eyed and thought of making a big name for themselvesin the theatre. But once they had learnt that the dirt roadhas many twists and turns in store, they shied away. Weplayed to near-empty houses. Following this, our actors didnot attend rehearsals. The group would disintegrate. Lack offinance and ramshackle venues was the last straw.On the other hand, white theatre was thriving and exploitingthis situation.But we still have some playwrights who write in Shonaand isiNdebele. Thompson Tshodzo is the most prominent.Most of the productions are in the format of townshipmusicals.I was once called upon to tighten up the plot of acommercially-inclined play for an established theatre company.The problem with these musicals is that in mostcases the lyrics do not follow the pattern of the content.STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981

Charles Rukuni64 We are up againstCharles Rukuniworks as a foreigncorrespondentand is alsoattached to ablack weeklynewspaper, Nioto— owned byMambo Press. Hisshort story 'Whostarted the War?'was published inForced Landing.Relevant theatre could not emerge and boldly be part ofcurrent culture. The situation was meant to squeeze out anyform of popular creativity.We wrote basically about social problems. There was amarked tendency among writers to shy away from politicalissues. Most of the publishing outlets were government-run.At the Literature Bureau where I am working it was unpopularto write against the government. Many of the blackwriters resorted to things like traditional life — witchcraft,broken family life, old society versus modern lifestyle. In asense, traditional writing became the norm.I published a sixty-page collection of short stories entitledComing of the Dry Season. Some of these stories I hadwritten while still at high school. The book was published in1972 and was later banned in 1974. Four years after thebanning, the censors decided to lift the ban.Every two years the Rhodesian censorship board used toreview bans on creative literature, apart from works whichcirculated as underground writings. If the reasons no longerapplied the book would be unbanned.So, in my case a big argument arose between a leadingacademic and his English Literature staff and the Censors. Hewas Irish and knew a lot about that country's protest literature.He made the point that the book was not even in thetradition of protest literature. His major point was that thereis a difference between literature and propaganda. Thoughnot articulate enough, the book did at least pinpoint wheresome of the problems lay.Among the reasons for the banning was this: a characterwitnesses a harrowing scene where somebody is knockeddown by a car. Some blacks converge and ask the eye-witnesswho's done it. Without wasting time he says, 'That boer overthere.'Because of that line, the censors thought the book wouldcause racial friction.Professor McLachlan at the Zimbabwe University andother people at the teaching colleges came out boiling againstthe censors. Funnily enough, it was two years after the bookwas published that they first noticed it. In fact someonebumped into it while doing a thesis on Zimbabwe/Rhodesialiterature since 1900. This was how they first noticed Comingof the Dry Season. The book was published by OxfordUniversity Press — their branch in Nairobi, Kenya. Casualreaders were also in the dark about it until ProfessorMcLachlan decided to set it for his first year students.*Colonial Hangovers"We are up against 'colonial' hangovers. The free flow of creativeactivity was checked when we were a subjected people.Relevant drama does not attract much interest from showlovers. It complicates matters. If, for instance, your play isdramatized at a hall next to a cinema, even if you advertise itas a free show, people will flock into the cinema. I'm notsaying that films wouldn't have a large following anyway, ofcourse. They would, even when what we had on the screenwas first censored by the Publications Board in Johannesburgand then the local censors, here. Films distributed by Ster-Kinekor arrived here 'third-hand'.The Literature Bureau under the aegis of the governmentused to keep manuscripts for, say, three years before decidinganything. Most of the writers were discouraged. TheBureau was interested only in Shona and Ndebele writings.Most of the contributors were prominent people who hadreceived their education in British countries. For them writingwas only a show and they felt obliged to pass on theiracquired knowledge. An ordinary person might have hadmore to say, but lacked the necessary expertise.Peasants in the rural areas received more political education.They endured hostilities from both the white armyand the black reactionaries. But they fought back, and cameto know their history far better than any of us here in thecities. They fought to abolish the Tribal Trust Lands. Theyhad finger-tip contact with vakomana. They came to know alot about the liberation struggle. They were better off thanblacks who went to work at 8.30 a.m., had a big lunch,knocked off at 5.00 p.m. and after that went to a pub. Thenthe same thing the following day, forever.Did Rhodesian P.E.N, help?The Rhodesian P.E.N, did not create opportunities fornew writers. Instead they acknowledged works which werealready published: be it in the country or abroad. In theirliterary contests, the judges seemed prejudiced in favour ofworks which were not banned in Zimbabwe then. They alsoseemed to me to be influenced by what was currently doingwell on the book market.Were the writers able to find a way of getting their workspublished?Not many came out. There was a problem from thefinancial aspect. I don't know what happened to an artassociation which was meant to take a constructive line onthis issue. Most people preferred to stand by without reactingwhile the national leaders were still in prison. You shouldhave seen the way university students reacted when they readabout the resurgence of writing by blacks in your owncountry.Then there was censorship, too. The result is that writerslike Dambuzo Marechera of The House of Hunger fame arenot even known in their own country. They are established'outside' rather than 'inside'. Internally, there are a few likePatrick Chakaipa who are most popular. Thompson Tshodzois well-known as a Shona playwright. Their works get airedon the radio — sponsored by business concerns like theColgate-Palmolive firm.Cultural resistance under the Rhodesian regime was in apassive phase. The trash that was put out during those days isstill with us.aSTAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981 19

Poetry786/Monnapule Lebakeng, Senzo Malinga, James Matthews.THE DYING GROUND . . .The elephants cameand brought with thema crookery of Godand brotherhood,took our verdant landwith gunpowder and psalmsand proclaimed a covenantin his name.Today, the fetters bite deepercruelty is resolute,genocide defined.Beyond Azania,black children eat manhoodfrom bloody potsand freedom is sownwith the seeds of valiant menThe harvest is bitter for the settlers and now,the last exodus gathers frenzy.The trail points Southwardto the last outpost(a haven to their whiteness).And like elephants,sensing the final hourthey hurry to the sacred sand(our conquered land)But let them comeO let the white elephants draw near!Illustration,MogorosiMotshumiWhat would be their refugeWill yet becomeTheir Dying Ground . . .786/Monnapule Lebakeng(It is known that elephants, when sensing that deathis near, walk for thousands of miles to a special 'dyingground' where they lay themselves down withoutfood or drink until they die . . . )AT WAR WITH THE PREACHERMANMy armful of goat skinsCaptures the eyes of the preacherman;I meet him on the shop verandah.He tells me I have to changemy evil ways;I go home curisng,<strong>Dec</strong>laring war against the preacherman.Later he comes to my placeAccuses me of deflecting peoplefrom the right way to Heaven;I in turn call on my godsTo deliver their godly angerupon this insolent preacherman;For I do not liveThat I may go to Heaven,But that I may have supper tonight.Senzo MalingaTRIP TO BOTSWANAi had a tasteof freedomthe first cautious sipcausingan unexperienced delight ofsensesmy soul outpaced the girdedwingstransporting me from forcedconfinementmy soul welcomed myarrivalit stilled my tremblingfleshas a woman and man embracedthough their colours were incontrastno hostile hand ripped themapartlove blossoming on theirfacesmy eyes became an eagerspectatorto the manifestations offreedomwhere within my captivity i wasdeniedfilled with the fruit offreedommy return holds nofearof the horror of myslaughterhouseJames Matthews20 STAFFRIDER, DECEMBER <strong>1980</strong>/JANUARY 1981