AACN Synergy Model for Patient Care - American Association of ...

AACN Synergy Model for Patient Care - American Association of ...

AACN Synergy Model for Patient Care - American Association of ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Usingthe<strong>AACN</strong><strong>Synergy</strong><strong>Model</strong><strong>AACN</strong> <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong><strong>for</strong> <strong>Patient</strong> <strong>Care</strong>Case Study <strong>of</strong> a CHF <strong>Patient</strong>Sonya Hardin, RN, PhD, CCRN, CSLeslie Hussey, RN, PhDrole as a clinical nurse specialist(CNS)/adult nurse practitioner(ANP). The advanced practice nursewith a CNS/ANP degree can have asignificant impact on healthcare bypreventing chronic illness and promotinghealthy lifestyles and influencethe delivery, cost, and quality<strong>of</strong> healthcare to persons withchronic illness. 2The <strong>AACN</strong> <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong> <strong>for</strong><strong>Patient</strong> <strong>Care</strong> describes a framework<strong>for</strong> nursing practice. The key to thismodel is the linkage <strong>of</strong> patient characteristicswith nurse competenciesto achieve optimal patient outcomes.1 The <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong> is readilyadaptable to the acute care or criticalcare setting when the patient is criticallyill and the intensive care nurselinks his or her own competencies tothe patient’s characteristics. However,not all acute care is conductedAuthorsSonya Hardin is an assistant pr<strong>of</strong>essorand coordinator <strong>of</strong> the MSN/MHA programat the School <strong>of</strong> Nursing, University<strong>of</strong> NC at Charlotte, NC.Leslie Hussey is an associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor atthe School <strong>of</strong> Nursing, Chair Adult HealthNursing Department, University <strong>of</strong> NC atCharlotte.To purchase reprints, contact The InnoVisionGroup, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656.Phone, (800) 809-2273 or (949) 362-2050 (ext532); fax, (949) 362-2049; e-mail,reprints@aacn.org.within the walls <strong>of</strong> the hospital setting.Today’s healthcare environmentmandates that patients with seriousdiseases live in their homes, causingthe need <strong>for</strong> acute and critical caresettings to reach out to their patientsnot only to assist them in maintaininga quality <strong>of</strong> life but also todecrease costs <strong>of</strong> hospital readmissions.This situation is especially true<strong>for</strong> patients with chronic heart failure(CHF). In the United States, manypatients with CHF regularly visit CHFclinics that are run by advanced practicenurses; these clinics assistpatients with maintaining and <strong>of</strong>tenimproving their state <strong>of</strong> heart failure,while also proving cost-effective.The <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong> provides theframework <strong>for</strong> nurses to managecomplex clients experiencing acuteexasperation <strong>of</strong> their illness and towork toward reducing the trajectory<strong>of</strong> the illness. The purpose <strong>of</strong> thisarticle is to discuss the application <strong>of</strong>The <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong> to an ambulatoryCHF clinic. We will discuss thecharacteristics <strong>of</strong> a patient whovisited a local clinic, with theadvanced practice nurse holding aBackground <strong>of</strong> CHFCHF is a major public healthproblem; it is the most commondiagnosis <strong>for</strong> people older than 65years <strong>of</strong> age who are dischargedfrom hospitals. CHF is a progressiveand chronic disease that limitspatients’ functional status andseverely lowers their quality <strong>of</strong> life.Currently, CHF is the number onediagnosis <strong>of</strong> Medicare beneficiaries,costing $10 to $30 billion annually. 3Although significant advances havebeen made in determining both thepathophysiology and therapy <strong>for</strong>CHF, there has been surprisingly littlechange in mortality rates over thepast 4 decades. 4 The 5-year mortalityrate <strong>for</strong> patients with symptomaticheart failure is almost 50%, and upto 40% <strong>of</strong> these deaths are sudden. 5CHF not only increases mortalitybut also has a dramatic effect onpatients’ functional ability and quality<strong>of</strong> life. Nearly 1 million patientswith CHF cannot live their liveswithout some restriction on activitybecause <strong>of</strong> the signs and symptoms<strong>of</strong> heart failure. 6Data indicate that between onethird and one half <strong>of</strong> heart failurereadmissions, particularly thoseCRITICALCARENURSE Vol 23, No. 1, FEBRUARY 2003 73

Usingthe<strong>AACN</strong><strong>Synergy</strong><strong>Model</strong>occurring within 90 days, are preventable.7 Factors that contribute topreventable hospitalizations areinadequate patient and caregivereducation, poor symptom control,insufficient social support, andinadequate discharge planning. 8Successful management <strong>of</strong> peoplewith CHF <strong>of</strong>ten includes long-termlifestyle adjustments by patients andfamilies. Lifestyle adjustments focuson modifications in diet and activities,adherence to a complex medicationregimen, and the need tomonitor symptoms. The success <strong>of</strong>lifestyle adjustments depends notonly on the person with CHF butalso on his or her social support. 8In the early stages, patients withheart failure may have minimalphysical limitations and symptoms.In later stages, ordinary daily activitiesbecome difficult, even at rest.Typically, the first key indicator <strong>of</strong>transition from early- to late-stageCHF is hospital admission.Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, both physical andpsychosocial interventions typicallybecome aggressive only during thelate stages <strong>of</strong> heart failure, which isusually too late to significantly affectmortality. This delay <strong>of</strong> interventionis partly due to the fact that patientsin early stages <strong>of</strong> CHF do not seekmedical treatment until their conditionrequires hospitalization.Because <strong>of</strong> the incidence and cost<strong>of</strong> CHF, many organizations havedeveloped innovative specializedclinics managed by advance practicenurses to provide intensive outpatientambulatory care <strong>for</strong> the CHFpopulation. These clinics were<strong>for</strong>med to enhance the appropriateuse <strong>of</strong> therapies and to bring aboutdesired health maintenance anddecreased rehospitalization. Suchclinics typically provide primarycare, counseling, education, andintensive follow-up. Numerous studiesshow that improved outcomescan be obtained through such nursemanagedclinics. 9,10Most CHF clinics operate withinthe outpatient setting, near a hospital.Criteria <strong>for</strong> admission to suchclinics include but are not limited to:ejection fraction <strong>of</strong> 0.40 or less, NewYork Heart <strong>Association</strong> class II to IVas determined by a physician, readmissionto the hospital 1 or moretimes in the past year, and a history<strong>of</strong> CHF. These clinics are managedby advanced practice nurses who areeither CNSs or ANPs and who arethe primary providers <strong>of</strong> care in consultationwith the medical director<strong>of</strong> the clinic.<strong>Patient</strong>s attend the clinic fromtwice a week to once a month; theyare reassessed at each visit and evaluated<strong>for</strong> continued therapies andeducation. Advanced practice nursesare excellent candidates to managethis complex population. Theirinterventions can result in adecrease in the readmission rate andan improved quality <strong>of</strong> life. Throughtheir education, nurses learn toapproach a patient holistically, integratingmany aspects <strong>of</strong> care. Thisintegration is key to the success <strong>of</strong>patient management and leads topositive outcomes. Readmission <strong>of</strong>CHF, along with resultant costs <strong>of</strong>hospitalization is decreased. <strong>Patient</strong>involvement in treatment demandsthe skill, expertise, and education <strong>of</strong>the nurse, not only in the initialassessment, but also in the ongoingcoaching process. Advanced practicenurses today, and increasingly in thefuture, will become primary careproviders <strong>for</strong> this important group<strong>of</strong> patients. Nurse-based models <strong>of</strong>care must be tested to determinetheir effectiveness and generalizabilityto recipients <strong>of</strong> healthcare.Sophie’s StorySophie, an 82-year-old African<strong>American</strong> woman, had New YorkHeart <strong>Association</strong> class III CHF. Shewas a widow, lived alone, and hersole financial support was SocialSecurity. She had been hospitalizedtwice in the past 18 months <strong>for</strong> exacerbations<strong>of</strong> CHF. She had had astroke, which had left her dependenton a cane <strong>for</strong> ambulation. She hadhypertension, osteoporosis, atrial fibrillation,and diabetes mellitus type2, which was controlled with diet;also, she took oral hypoglycemics.Sophie had a daughter who caredabout her but was unable to provideany supplemental financial support.Sophie took the following medications:an angiotensin-convertingenzyme inhibitor, digoxin, potassium,fosinopril sodium, coumadin,and furosemide. Her medicationscost her approximately $350 permonth. Because she did not have anyother insurance except Medicare,Sophie payed <strong>for</strong> medications herself.She did not drive but used publictransportation to travel to the clinicand <strong>for</strong> other trips such as going tothe grocery store and church. Sophiecame to the CHF clinic every 2 weeks.On the morning <strong>of</strong> one visit,Sophie was complaining <strong>of</strong> slightshortness <strong>of</strong> breath. She had gained3 lb since her last visit. Her bloodpressure was elevated to 176/94 mmHg—it was normally around 130/80mm Hg. Her pulse was 106beats/min and irregular, and shestated that her shoes did not fit soshe had to wear her slippers. Her74 CRITICALCARENURSE Vol 23, No. 1, FEBRUARY 2003

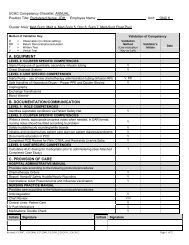

Usingthe<strong>AACN</strong><strong>Synergy</strong><strong>Model</strong>Table 2 The competencies needed by Sophie’s nurseClinical judgementAdvocacy and moralagencyCaring practicesFacilitation <strong>of</strong> learningCollaborationSystems thinkingResponse to diversityClinical inquiryAnalyze assessment data and make decisions based upon theneeds <strong>of</strong> the clientSupport patient in her decisions to remain independentImplement a process to ensure that resources are obtained <strong>for</strong>the patientEnsure that Sophie understand her disease process,medications and results <strong>of</strong> choices in relation to her healthUtilize resources in the community to meet the needs <strong>of</strong> thepatientAnticipate possible strategies to ensure compliance withinterventionsRespect the clients values and beliefsQuestion the client to analyze which innovative strategieswould be most successful with the client.ConclusionThe <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong> is applicableto a variety <strong>of</strong> settings. Specifically,the use <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong> in anambulatory setting is an example <strong>of</strong>the flexibility <strong>of</strong> the model. Theadvanced practice nurse in anambulatory clinic uses the competencesdescribed in the model toensure optimal outcomes <strong>for</strong> thepatient. The <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong> can beapplied in numerous settings andcan guide the practice <strong>of</strong> advancedpractice nurses.The nurse had to develop, integrate,apply, and evaluate a variety <strong>of</strong>strategies to meet the needs <strong>of</strong> thepatient. 12 The strength <strong>of</strong> an ambulatorysetting is that protocols arein place to do follow-up phone callswith patients to ensure continuedprogress and answer questions thatcan occur after the visit. Typically, anadvanced practice nurse would usesystems thinking to develop proactivestrategies that could ensure improvedutilization <strong>of</strong> services through theCHF clinic <strong>for</strong> Sophie. These strategiescould include sample medicationsto be given during the last week<strong>of</strong> each month or to investigate thepotential <strong>for</strong> Sophie to be involved inindigent programs sponsored bypharmaceutical companies.Lastly, the nurses must respondto the diversity presented by eachpatient. In Sophie’s situation, thenurse must respect the client’s wishesto maintain her value <strong>of</strong> independenceand pride in not accepting charity.Also, the nurse must supportSophie in her preference <strong>for</strong> foodchoices. A response to diversitymeans recognizing cultural or ethnicdifferences in the provision <strong>of</strong> care. 13All the nurse competencies withinthe <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong> were importantin the care <strong>of</strong> Sophie.OutcomesThe advanced practice nurse inthis situation utilized the competenciesin the model to meet the needs<strong>of</strong> the patient. Sophie was connectedwith the local Meals on Wheels program,which agreed to provide 1 hotmeal per day. In a follow-up phonecall, Sophie reported that enoughfood was delivered every day so thatshe could actually save some <strong>of</strong> it tohave with dinner. The CNS/ANPadjusted Sophie’s medicationregime, followed up with phone callsto her home on day 3 and 5 to ensurecompliance and to answer questions.A decision was made by the patientto allow the advanced practice nurseto seek in<strong>for</strong>mation regarding indigentprograms <strong>for</strong> several <strong>of</strong> thedrugs and to utilize drug samples atthe end <strong>of</strong> each month until a programcould be obtained <strong>for</strong> theclient. The client also acknowledgedher understanding <strong>of</strong> following aprotocol to weigh herself daily and tocall into the clinic <strong>for</strong> a weight gain<strong>of</strong> greater than 1 lb <strong>for</strong> possible fluidrestrictions and drug adjustments.References1. Curley MAQ. <strong>Patient</strong>-nurse synergy: optimizingpatients’ outcomes. Am J Crit <strong>Care</strong>.1998;7:64-72.2. UNC Charlotte Web site. Available at:http://www.uncc.edu/colleges/health/depfacstaff_frame.htm. Accessed October2002.3. Lenfent C. Cardiovascular research: an NIHperspective. Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;4:4-5.4. Ho KKL, Anderson KM, Kannel WB,Grossman W, Levy D. Survival after theonset <strong>of</strong> congestive heart failure inFramingham Heart Study Subjects.Circulation. 1993;88:107-115.5. Singh SN. CHF and arrhythmias: treatmentmodalities. J Cardiovasc Eletrophysiol.1996;89:89-97.6. Konstam M, Dracup K, Baker D, et al. HeartFailure: Evaluation and <strong>Care</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Patient</strong>s WithLeft-Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction. ClinicalPractice Guideline No.11. Rockville, Md:Agency <strong>for</strong> Health <strong>Care</strong> Policy andResearch; 1994. Publication No. 94-0612.7. Shah NB, Der E, Ruggerio C, Heidenreich P,Massie B. Prevention <strong>of</strong> hospitalizations <strong>for</strong>heart failure with an interactive home monitoringprogram. Am Heart J. 1998;135:373-378.8. Wehby D, Brenner PS. Perceived learningneeds <strong>of</strong> patients with heart failure. HeartLung. 1999;28:31-40.9. McAlister FA, Keo KT, Taher M, et al.Insights into the contemporary epidemiologyand outpatient management <strong>of</strong> congestiveheart failure. Am Heart J.1999;138:87-94.10. Hendrick A. Cost-effective outpatient management<strong>of</strong> persons with heart failure. ProgCardiovasc Nurs. 2001;16(2):50-56.11. Hardin S, Hussey L. The <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong> inpractice: clinical inquiry. Crit <strong>Care</strong> Nurse.April 2001;21:88-91.12. Moloney-Harmon PA. The <strong>Synergy</strong> <strong>Model</strong>:contemporary practice <strong>of</strong> the clinical specialist.Crit <strong>Care</strong> Nurse. April 1999;19:101-104.13. Doble RK, Curley MAQ, Hession-Labard E,Marino BL, Shaw SM. Using the <strong>Synergy</strong><strong>Model</strong> to link nursing care to diagnosisrelatied groups. Crit <strong>Care</strong> Nurse. June2000;20:86-92.76 CRITICALCARENURSE Vol 23, No. 1, FEBRUARY 2003