park management plan marakele park management plan - SANParks

park management plan marakele park management plan - SANParks

park management plan marakele park management plan - SANParks

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

This <strong>plan</strong> was prepared byDr Stefanie Freitag-Ronaldson, Charles Trenneryand Fhatuwani Hendrick Mugwabanawith significant inputs and help from Dr Harry Biggs, Dr Rina Grant Biggs,Llewellyn Foxcroft, Navashni Govender, Dr Holger Eckhardt, Jacques Venter, DrAndrew Deacon, Hendrik Sithole, Nick Zambatis, Dr Ian Whyte, Dr Mike Knight,Dr Stephen Holness, Antionet van Wyk, Edgar Nevuvhalani, Arrie Schreiber,Angela Gaylard, André Spies, Sibongile Masuku Van Damme.M A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N3

This <strong>management</strong> <strong>plan</strong> is hereby internally accepted and authorised as the legal requirement formanaging Marakele National Park as stated in the Protected Areas Act.DATE: 31 MARCH 2008AUTHORISATION______________________________Fhatuwani Hendrick MugwabanaPark Manager – Marakele National Park______________________________M MagakgalaRegional Manager – Northern Region______________________________Paul DaphneExecutive Director Parks______________________________Sydney SoundyChief Operating Officer______________________________Dr David MabundaChief ExecutiveRecommended to <strong>SANParks</strong> BoardName: _____________________________ Date: __________Ms Cheryl CaroulusChairperson – <strong>SANParks</strong> BoardRecommended to the Department of Environmental Affairs and TourismM A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A NName: _____________________________ Date: ___________Mr Marthinus van SchalkwykMinister – Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism4 5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYMarakele is one of the younger national <strong>park</strong>s in South Africa, initiated in 1986,proclaimed in 1994 as Kransberg National Park and expanded over the years fromthis core area to the current proclaimed area of some 90 000 ha and it is still in aphase of considerable expansion. The most important existing contractual agreementincludes Marakele Park (Pty) Ltd with respect to some 15 753 ha. FloristicallyMarakele is exceptionally rich, with representatives typical of fynbos, forest andKalahari systems. A rich diversity of <strong>plan</strong>t species as well as <strong>plan</strong>t communities andhabitats give Marakele a high conservation value and it lies on the edge of theSANBI delineated central bushveld biodiversity hotspot.The broad-level desired state of Marakele National Park has been set in conjunctionwith stakeholders in an explicit and focused way, highlighting key objectiveswhich need attention in the next 5 year <strong>management</strong> cycle. The desired state ofMarakele is based on a jointly agreed-upon vision and mission, vital attributes andhigh level objectives, developed in conjunction with stakeholders through theadaptive <strong>plan</strong>ning process. It is primarily set around biodiversity conservation andcooperative governance foci with a suite of thresholds, defining acceptable endpointsor envelopes around the biophysical desired state, for monitoring performancerelative to the desired state.Some aspects of the desired state are still open-ended, requiring longer-termstrategic decisions within the context of cooperative governance, as well as within<strong>SANParks</strong>’ core values, for example evaluation of alternative tourism and developmentmodels as well as boundary and large mammal herbivory scenarios.Gaining an understanding of vegetation communities, their interactions with herbivory,especially elephant utilisation, and ongoing baseline inventorisation andunderstanding of biodiversity heterogeneity patterns, processes and functions arepriorities. It is recognised that in this <strong>park</strong> it is essential to engage all partners andkey stakeholders and build the sustaining trusting cooperation that is so essentialfor the long-term success of Marakele.Park consolidation and expansion requires ongoingefforts backed by broad-scale constituency building andcooperative governance to enhance understanding andbuy-in for longer-term goals. This will be greatly facilitatedby making very explicit the variety of ecosystemgoods and services that the <strong>park</strong> can and will deliver tostakeholders. Hand-in-hand with these efforts are thereal need to address socio-political threats, especiallythrough ongoing conflict around elephant and predator<strong>management</strong> options. Additional threats requiringattention are the impacts of rampant development inthis region on the wilderness character and sense ofplace within and around the <strong>park</strong> as well as cultural heritageaspects.Given the desired state, the cross-links and priorities, thebroad costing for the five-year drive towards achievingthe desired state outlines both existing and projectedbudgets and costs. This costing includes all resources(but excludes research facilitation costs which are internalisedelsewhere in the organisation) believed to berequired to achieve realistic progress towards thedesired state. The fact that the resources required arehigher than historically allocated to Marakele NationalPark is the result of this report having made explicit whatis actually required to achieve that. Development of asmall but effective research facility will also greatlyenhance the potential of Marakele to attract muchneededresearch and monitoring partners.M A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N89

National DecisionMaking ContextPark DecisionMaking ContextStrategic ReviewMonitorProcess overviewNational & International Legislation<strong>SANParks</strong> Strategic FrameworkVision, Policies, Values, Objectives, Norms,Standards, IndicatorsProtected Area PolicyFrameworkPark Desired State5-Year CycleAdaptiveManagement ReviewSouth African National Parks (<strong>SANParks</strong>) has adopted an overarching <strong>park</strong> <strong>management</strong>strategy that focuses on developing, together with stakeholders, andthen managing towards a ‘desired state’ for a National Park. The setting of a <strong>park</strong>desired state is done through the adaptive <strong>plan</strong>ning process (Rogers 2003). Theterm ‘desired state’ is now entrenched in the literature, but it is important to notethat this rather refers to a ‘desired set of varying conditions’ rather than a staticstate. This is reinforced in the <strong>SANParks</strong> biodiversity values (<strong>SANParks</strong> 2006) whichaccept that change in a system is ongoing and desirable. Importantly, a desiredstate for a <strong>park</strong> is also not based on a static vision, but rather seeks refinementthough ongoing learning and continuous reflection and appropriate adaptationthrough explicit adoption of the Strategic Adaptive Management approach.The ‘desired state’ of a <strong>park</strong> is the <strong>park</strong>s’ longer-term vision (30-50 years) translatedinto sensible and appropriate objectives though broad statements of desiredoutcomes. These objectives areAnnual CycleImplementationand OperationsOVERVIEW OF THE SANPARKSMANAGEMENT PLANNING PROCESSPark Management PlanAnnual Operations Planderived from a <strong>park</strong>’s keyattributes, opportunities andthreats and are informed by thecontext (international, nationaland local) which jointly determineand inform <strong>management</strong>strategies, programmes andprojects. Objectives for national<strong>park</strong>s were further developedby aligning with<strong>SANParks</strong> corporate strategicobjectives, but defining themin a local context in conjunctionwith key stakeholders. Theseobjectives are clustered orgrouped into an objectiveshierarchy that provides theframework for the ParkManagement Plan. Within thisdocument only the higher levelobjectives are presented.However, more detailed objectives,down to the level ofoperational goals, have been(or where necessary are currently being) further developedin conjunction with key stakeholders and specialists.This approach to the <strong>management</strong> of a National Park isin line with the requirements of the NationalEnvironment Management: Protected Areas Act No. 57of 2003 (NEM: PAA). Overall the Park Management Planforms part of a National Planning framework for protectedareas as outlined in the figure on the left.Park Management Plans were not formulated in isolationof National legislation and policies. Management <strong>plan</strong>scomply with related national legislation such as theNational Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act,national <strong>SANParks</strong> policy and international conventionsthat have been signed and ratified by the South AfricanGovernment.Coordinated Policy Framework Governing ParkManagement PlansThe <strong>SANParks</strong> Coordinated Policy Framework providesthe overall framework to which all Park ManagementPlans align. This policy sets out the ecological, economic,technological, social and political environments ofnational <strong>park</strong>s at the highest level. In accordance withthe NEM: Protected Areas Act, the Coordinated PolicyFramework is open to regular review by the public toensure that it continues to reflect the organisation’s mandate,current societal values and new scientific knowledgewith respect to protected area <strong>management</strong>. Thisdocument is available on the <strong>SANParks</strong> website.Key functions of Park Management PlansThe key functions of this <strong>management</strong> <strong>plan</strong> are to:• ensure that the Park is managed according to thereason it was declared.• be a tool to guide <strong>management</strong> of a protected areaat all levels, from the basic operational level to theMinister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism;• be a tool which enables the evaluation of progressagainst set objectives.• be a document which can be used to set up key performanceindicators for Park staff.• set the intent of the Park, and provide explicit evidencefor the financial support required for the Park.This Management Plan for Marakele National Parkcomprises four broad sections1. The background to and outline of the desired state ofthe Park and how this was determined.2. A summary of the <strong>management</strong> strategies, programmesand projects that are required to movetowards achieving the desired state (obviously thesestrategies, programmes and projects can extend overmany years but here we present the <strong>management</strong>focus until 2010).3. An outline of the Strategic Adaptive Managementmethodology and strategies that will ensure that thePark undertakes an adaptive approach to <strong>management</strong>.It focuses <strong>park</strong> <strong>management</strong> on those criticalstrategic issues, their prioritisation, operationalisationand integration, and reflection on achievementsto ensure that the longer-term desired state isreached.4. Presentation of a high level budget.M A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A NFigure 1: Protected Areas <strong>plan</strong>ning framework1011

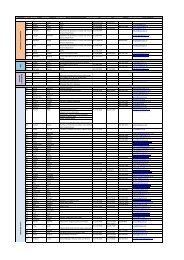

1. BACKGROUND TO AND FORMULATION OF THE DESIRED STATE FOR THE PARKThis section deals with the setting of a <strong>park</strong> desired state through the adaptive<strong>plan</strong>ning process (Rogers 2003), from the general to the specific, focusing onunique attributes of Marakele National Park. In the case of Marakele National Park,this was done entirely in conjunction with stakeholders and contractual partners.Invitation letters were sent to all major stakeholders and there were advertisementsin the local newspapers. The turnout was very good with representationfrom the Farmers Association, surrounding lodges, The Department of Agriculture,Economic Development & Environment as well as District and Local Municipalitiesthroughout the process.The term ‘desired state’ is now entrenched in the literature, but it is important tonote that this rather refers to a ‘desired set of varying conditions’ rather than astatic state. This is reinforced in the <strong>SANParks</strong> biodiversity values (<strong>SANParks</strong> 2006)which accept that change in a system is ongoing and desirable.1.1 The fundamental decision-making environmentThe three pillars of the decision-making environment are seen as the vision statement,the context, and thirdly, the values and operating principles. Althoughderived through a process, the mission is stated upfront, but much of the supportingmaterial which helped form it is captured under other headings further downthe document. As mentioned above, much of sections 1.1 and 1.2 were derivedthrough stakeholder engagement using the adaptive <strong>plan</strong>ning approach, and thusreflect a shared desired state derived jointly by integrating stakeholders’ desiresand <strong>SANParks</strong>’ mandate. This has resulted in a change in the vision for the <strong>park</strong>(from that historically derived by <strong>SANParks</strong>) and a suite of jointly agreed-upon highlevel objectives for this <strong>park</strong>. The expansion of these high level ideas were presentedas part of an integrated proposal of a <strong>management</strong> <strong>plan</strong> at a public meetingheld in terms of the NEM: Protected Areas Act on 4 September 2006.1.1.1 MissionINTRODUCTIONThe concept of an overarching vision for the broad cooperative governance spectrum(predominantly within the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve) emerged throughthe stakeholder workshops as one which will be crucial for the success of MarakeleNational Park within this regional context. Jointly, it was agreed that “we are proudstakeholders in the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve, with Marakele National Park asa “jewel in the crown”. The Waterberg Biosphere Reserve is a preferred adventureeco-tourism destination rooted in inclusive and honourable public/private partnerships.As partners we promote community participation and empowerment to bal-ance economic and social development with conservationof our ecological and cultural heritage”.Nestled within this broad context, the mission forMarakele National Park (<strong>SANParks</strong>) in the partnership isarticulated as “we promote the wise, efficient and integrated<strong>management</strong> of the biodiversity « of Marakele tomaintain, or repair, a wilderness character, and associatedbenefits to regional economic, social and educationaldevelopment.”<strong>SANParks</strong> recognises the need to balance the biodiversityand wilderness aspects of this <strong>park</strong> with the opportunitiesthat it presents for stimulating regional developmentand that this must all be effected through inclusive andhonourable cooperative governance approaches.« Biodiversity refers to the species diversity, habitat (structural)diversity and diversity of ecosystem processes.1.1.2 ContextThe range of values as well as social, technological ecological,economic, legal and political facts, conditions,causes and surroundings that define the circumstancesrelevant to Marakele National Park provide the “context”for decisions and are therefore important elements of anydecision making environment. These contextual issues arebroadly outlined below.1.1.2.1 Location and BoundariesTable 1: Private land included, by proclamation, into the national <strong>park</strong> by written permission of the landownerMarakele National Park is situated in the LimpopoProvince, roughly 15 km northeast of Thabazimbibetween latitudes 24 o 15’ and 24 o 32’ south and longitudes27 o 30’ and 27 o 40’ east. The <strong>park</strong> lies on theextreme south-western quadrant of the Waterberg massifand its adjoining lowlands to the west ((Map 1 – presentedin Appendix of Maps). The Kwaggasvlakte section ofthe <strong>park</strong> is currently disconnected from the main area ofthe <strong>park</strong> by the provincial Hoopdal road. Marakele is situatedin an area made famous by the works of poet andauthor Eugene Marais. There are a number of contractuallyincluded parcels of land which contribute to achievingthe vision and overall desired state of this national <strong>park</strong> asoutlined in Table 1 below.Marakele National Park falls under the Waterberg DistrictMunicipality and covers three local municipalities, namelyThabazimbi, Lephalale and Modimolle Municipalities.Marakele National Park is linked to the Waterberg DistrictMunicipality’s integrated development <strong>plan</strong> and all projectsare submitted to the municipality.The <strong>park</strong>’s airspace is regulated by Section 47 of theProtected Areas Act as 2500 ft (762 meters) above thehighest point (1800 meters on Marakele). Currently thereis only 1 helicopter landing pad available and in use onZandspruit.TITLE DEED FARM PORTION EXTENT OWNER SECTION GG PROCLA PERIOD RESTRICTIONSNODATET21440/2001 Remainder Portion 0 67.9290 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29of Hoopdaal 96T21441/2001 Hoopdaal 96 Portion 6 42.8266 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29T21441/2001 Hoopdaal 96 Portion 7 192.2528 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29T21440/2001 Hoopdaal 96 Portion 11 222.6003 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29T96214/1999 Diamant 228 Portion 19 1284.7980 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29T4635/2001 Klipdrift 231 Portion 2 873.6626 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29T96214/1999 Klipdrift 231 Portion 3 873.6626 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29T96214/1999 Klipdrift 231 Portion 4 873.6626 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29T96214/1999 Klipdrift 231 Portion 5 873.6626 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29T4806/2001 Retseh 594 Portion 0 878.9510 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29T3295/2001 Remainder Portion 0 1708.0761 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22335 2001/05/29of Waterval 267T30444/2001 Remainder of Portion 0 1997.5010 CCG108 2B(1)(b) 22492 2001/07/27 30 yearsBuffelspoort 265T41029/1994 Vygeboom- Portion 4 534.4720 Aapiesrivier- 2B(1)(b) 16527 1995/07/14fontein 239<strong>park</strong> CCT74496/1991 Waterval 267 Portion 1 1713.0640 NPT of SA 2B(1)(b) 25562 2003/10/17T74496/1991 Jagtersrus 418 Portion 0 1000.0000 NPT of SA 2B(1)(b) 25562 2003/10/1750 years from14 July 1995and shall contimuethereafteruntil terminatedby 6months notice99 years from17 October2003 with anoption torenew for further25 yearDevelopmentby the ownerNoneM A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N1213

this is reflected in the regional Integrated Development Plan that is focussed ontourism, agriculture and mining. The levels of unemployment within the urbanisedcommunities in the Thabazimbi Municipal Area are relatively high (Table 1).Particularly high unemployment and low income levels are found in Regorogile,with many of the youth not attending school. There are also a number of farmbasedworkers with varying levels of employment and literacy. This poor previouslydisadvantaged community contrasts sharply with other stakeholders.The mining sector plays a major role in job creation and has been the major economicengine of this region. Much hope is centred on the emerging biospherereserve concept (the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve is registered with UNESCO)and recent developments and upswings in nature-based tourism opportunities(including ecotourism and hunting) as an alternate long-term socio-economic driverwithin the region. This is evidenced by both the many and varied existing agreementsbetween parties as well as by the diversity of tourism infrastructure externalto the <strong>park</strong> which caters for the upper and lower income eco-tourist market,although there is much less available for middle income tourists.1.1.2.6 International and national contextAs in all <strong>park</strong>s, a wide range of national legislation is relevant to Marakele NationalPark. Areas of high relevance in the case of Marakele include biodiversity and culturalheritage legislation. Marakele’s situation and contribution to the UNESCOregisteredWaterberg Biosphere Reserve forms an important component of theinternational context for this <strong>park</strong>.Table 2: Immediate Community Analysis (taken from STATS SA data from the last national census)Community Population No of households % households % female headed % unemployed personswith income households with over the age of 18 years< R600 p/m income < R600 p/mThabazimbi 4 416 1 323 29,2% 15,3% 23,6%Regorogile 7 605 2 299 45,5% 21,4% 33,8%1.1.3 Values and Operating PrinciplesOur values are the principles we use to evaluate the consequencesof actions (or inaction), to propose and choosebetween alternative options and decisions. Values maybe held by individuals, communities, organisations oreven society and the values articulated below reflect thevalues of the individuals in the Marakele stakeholdergroup, including <strong>SANParks</strong> and the contractual partners.• We have mutual respect for cultural, economic andenvironmental differences within and across theregional spectrum of cooperation and agreements.• Recognising that ecosystems and biodiversity arecomplex, and that we will seldom have all the informationwe want to make decisions, we adopt a ‘learningby doing’ approach to their <strong>management</strong>.• We have a culture of honesty, cooperative sharing ofexpertise, and of empowerment and advancement ofall parties.• Clear definition of each stakeholder group’s expectations,and how we balance the distribution of costsand benefits, helps us avoid conflict.• We keep our expectations and the distribution ofcosts and benefits within the cooperative governancerelationships explicit, transparent and within biodiversityconstraints.These should be read in conjunction with the <strong>SANParks</strong>’overarching conservation values, namely that we:• Respect the complexity, as well as the richness anddiversity of the socio-ecological systems making upeach national <strong>park</strong> and the wider landscape and context;respect the interdependency of the formativeelements, the associated biotic and landscape diversity,and the aesthetic, cultural, educational and spiritualattributes and leverage all these for creative anduseful learning.• Strive to maintain natural processes in ecosystems,along with the uniqueness, authenticity and worth ofcultural heritage, so that these systems and their elementscan be resilient and hence persist.• Manage with humility the systems under our custodianship,recognising and influencing the wider socioecologicalcontext in which we are embedded.• Strive to maintain a healthy flow of ecosystem andcultural goods and services (specifically preservingcultural artefacts), and to make these available, alsothrough access to national <strong>park</strong>s, thereby promotingenjoyment, appreciation and other benefits for people.• When necessary, intervene in a responsible and sustainablemanner, complementing natural processes asfar as possible, using only the level of interferenceneeded to achieve our mandate.• Do all the above in such a way as to preserve alloptions for future generations, while also recognizingthat systems change over time.• Acknowledge that conversion of some natural andcultural capital has to take place for the purpose ofsustaining our mandate, but that this should nevererode the core values above.• More detail about the above and listings of othermore generic corporate <strong>SANParks</strong> values and operatingprinciples, as well as a list of generic policies, areavailable (<strong>SANParks</strong> 2006).1.2 Vital attributes underpinning the valueproposition of the <strong>park</strong>The following vital attributes (i.e. the few most importantcharacteristics/properties of the system to be managed;these may be social, technical, ecological, economicand/or political) have been identified, together withstakeholders, as making this <strong>park</strong> unique, or at least veryspecial in its class. Important determinants and threatshave also been identified. Determinants are those factorsor processes that determine, strengthen or ensure persistencewhile threats are those factors or processes thatthreaten, erode or inhibit these attributes or their determinants.Threats can also be factors within, or outside, apartnership that undermine its values and inhibit the pursuitof the mission or future desired state.This information helps focus the exact formulation of <strong>park</strong>objectives, which must strengthen positive determinantsand weaken or remove threats, so that objectives areappropriate to the uniqueness and special nature of thisnational <strong>park</strong>. In this way the <strong>management</strong> <strong>plan</strong> is customizedin its fullest local extent, without detracting fromsome of its more generic functions. These vital attributeshelp us develop the real value proposition of the <strong>park</strong>.Vital attributes of Marakele National Park:• There is a diversity of stakeholders, each of whichbrings knowledge and expertise to the cooperationbut <strong>SANParks</strong> is recognised as being able to provideparticular skills in conservation and tourism.• Marakele is an important element of the IUCN-recognisedWaterberg Biosphere Reserve and falls within aSouth African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI)recognised biodiversity hotspot.• Eco-tourism provides a long term economic option inthe region. There is currently a good diversity ofadventure tourism activities and infrastructure in theregion based on both cultural (pioneer country) andresource (wildlife and outdoor) markets.• The mountain massif provides a large altitudinalrange, a wide-open-space visual aesthetic and associatedbiodiversity within a short distance. Many headwaterstreams arise within the <strong>park</strong>.M A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N1617

• Vital biodiversity attributes include the vulture breeding colonies, cycads, anda very wide range of vegetation types from Kalahari bushveld in the lowlands,to fynbos elements on the mountain.• The area is malaria and bilharzia free and located near a large regional market(Gauteng).Key determinants of these vital attributes:• A local topography that presents a spectacular and undeveloped massif.• High ecological integrity of the diverse landscapes and vegetation types.• A regional land use that is highly compatible with biodiversity and NationalProtected Area conservation.• Good tourist flow from regional, national and international sources.• The core conservation area is a declared National Park and is within a SANBIrecognised biodiversity hot spot.Key threats to Marakele vital attributes and determinants:• There is currently a low level of trust among stakeholders and partners andlines of communication, accountability and decision-making between these arepoor.• There are currently no established ‘rules of the game’ for the spectrum ofcooperation and agreements.• There is no clear, agreed upon economic model for either the MarakeleNational Park, or Waterberg Biosphere Reserve, making it difficult to assess theeconomic viability of the <strong>park</strong> or potential tourism products.• Development within Marakele and it surroundings is currently proceeding withoutproper guidelines. Regional guidelines are being developed but must stillbe implemented.• Marakele does not currently seem to be delivering to tourist expectations, particularlyin respect of being a ‘big five’ <strong>park</strong>. Poor roads also contribute totourist dissatisfaction.• There is no clear strategy for conservation of Marakele itself, or for its role inthe Greater Marakele Region. It is therefore difficult to (1) judge the biodiversityconstraints for development, (2) provide the basis for effective biodiversity<strong>management</strong> (including <strong>management</strong> of elephant and predator populationsand alien species), and (3) define cost/benefit relationships of resource sharingamong partners and collaborators.• The possible expansion of mining activities along the southern <strong>park</strong> boundaryconstitutes a significant threat, especially to the ambience of the <strong>park</strong> and surrounds.1.3 Setting the details of the desired state forMarakele National ParkThe desired state is based on a collectively developedvision of a set of desired future conditions (that are necessarilyvarying), integrating ecological, socio-economic,technological, political and institutional perspectiveswithin a geographical framework. The vision (within contextand values), vital attributes of Marakele and objectives(which are aimed at overcoming threats to ensurethe persistence of vital attributes and/or their determinantsfor this national <strong>park</strong>), together with the thresholdsof potential concern (TPCs) and the zonation <strong>plan</strong> togethermake up the desired state of Marakele National ParkIn the adaptive <strong>management</strong> of ongoing change in socioecologicalsystems, thresholds of concern are the upperand/or lower limits of flux allowed, literally specifying theboundaries of the desired state. TPCs specify the measurable“boundaries” of the desired state, flowing out ofthe objectives developed for the <strong>park</strong>. If monitoring (orbetter still monitoring in combination with predictivemodeling) indicates certain or very likely exceedancesbeyond these limits, then mandatory <strong>management</strong>options of the adaptive cycle are prompted for evaluationand consideration.The <strong>park</strong>’s Conservation Development Framework (whichincludes a zonation <strong>plan</strong>) details the spatial targets andconstraints through specification of strategic land useintent for the Marakele National Park for the next 20-30years. However, for Marakele, a comprehensive spatiallybasedregionally-embedded framework, which includesmultiple scales of detail still needs to be pulled together,and this full CDF will be available at the first iteration ofthis <strong>plan</strong> in 5 years time.1.3.1 An objectives hierarchy for Marakele National ParkUsing the Marakele mission, context and values, andbearing in mind particularly the vital attributes (all ofwhich were articulated jointly with stakeholders), the followingset of <strong>park</strong> objectives have been determined,which together with the specific articulated thresholds ofpotential concern and zonation <strong>plan</strong> outline the broadambit of the desired state of the <strong>park</strong>.Figure 2: Desired state articulation (components shown in orange blocks) within the overall strategic adaptive <strong>management</strong> frameworkas embraced by <strong>SANParks</strong>.M A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N18 19

Outlined below (Figures 3a and 3b) are the first two high-level tiers of the objectiveshierarchy developed for Marakele. In order for Marakele to move towardsrealising it’s jointly agreed-upon mission, there will need to be particular attentiongiven to the development and nurturing of a relationship based on trust and equitableempowerment across the full cooperative governance spectrum within andaround this <strong>park</strong>. There will need to be a concerted biodiversity conservationeffort, underpinned by the location of Marakele within a national biodiversity priorityarea, with specific attention being paid to ecosystem processes. Furthermore,in order to maintain the unique and dwindling wilderness resource, <strong>park</strong> <strong>management</strong>must focus on both influencing and instituting appropriate economic modelsand development around and within the <strong>park</strong>. Such an approach is necessitatedto both service the broader aims of the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve as wellas the national custodianship mandate of <strong>SANParks</strong> and Marakele itself. Furtherdetails can be found in Appendix 1.1.3.2 Thresholds of concern and other exact conservation targetsAs suggested above, thresholds of potential concern (TPCs) are the upper and/orlower limits of ecosystem flux allowed, literally specifying the boundaries of thedesired state. Considering the biophysical objectives stated in Figures 3a and 3babove and the detail in Supporting Document 1, the following TPCs are provisionallytabled for Marakele National Park:a. Vegetation composition TPCs – These will be set for indicator <strong>plan</strong>t species inthe mountain sourveld area, specifically for species that would indicate whenthese areas are changing at unacceptable rates. These TPCs are proposedsince this is a unique landscape, and broad community changes may not besensitive enough to indicate unacceptable increased levels of utilisation.b. Woody structure/abundance and herbaceous cover TPCs - Over time, as thevegetation adjusts to impacts of herbivory (from which it had effectively beenprotected for decades), a change in the dominant species could be included asa TPC. Nevertheless, TPCs should not be too conservative, and should allowvariation between impact tolerant and intolerant communities, and be measuredacross multiple scales.Figure 3(a): An objectives hierarchy for Marakele National Park – the mission and highest level objectives.M A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N20 21

c. Herbivore TPCs - These TPCs are recommended as starting points until suchtime as generated understanding suggests a need for amendment. These initialTPCs reflect on species that are newly established within the <strong>park</strong>, however,when the <strong>park</strong> is well established a TPC for a change in dominant speciesmay be developed to specify anticipated trajectories of unacceptable increasesin or dominance of one species over others.d. Invasive alien TPCs - Alien threat and invasion TPCs will be applied as per perceivedrisk at Marakele, including TPCs for new invasions, spread and densificationof selected established invaders.e. TPCs for species of conservation concern – TPCs have been set for the globallycritically endangered black rhino (specifically the south-western Dicerosbicornis bicornis) such that a TPC is triggered with any unexplained nonincreasein population growth rate between two surveys.In addition, in future, once long-term river flow and quality data have been evaluated,TPCs may be set for these parameters as an indicator of the water-relatedgoods and services Marakele is delivering to surrounding areas.1.3.3 Conservation Development FrameworkA full Conservation Development Framework (CDF) has not yet been set forMarakele National Park. However a sensitivity value map has been produced((Appendix 2 - Map 5) and a practical zonation (further discussion under 2.1.1;Appendix 2 - Maps 3-6) is available and in use to guide development. There willbe a full CDF available at the first iteration of this <strong>plan</strong> in 5 years time. The worktowards a full CDF will, by its very nature, also ensure greater and more integratedalignment with the regional Spatial Development Framework (SDF) andIntegrated Development Plans (IDP). This will be essential to achieving theMarakele desired state in the medium- to long-term and will be a priority goingforwards. An issue of particular stakeholder interest is <strong>SANParks</strong>’ intention towork towards deproclamation of a section of the Hoopdal road (which currentlyseparates the Kwaggasvlakte section of the <strong>park</strong> from the main area of the <strong>park</strong>).Figure 3(b): An objectives hierarchy for Marakele National Park – the next level of resolution of the biodiversity objectives.M A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N22 23

THE PROTECTED AREAS MANAGEMENTPLANNING FRAMEWORK2. PROGRAMMES TO ACHIEVE THE DESIRED STATEThis section deals with all the discrete, but often interlinked, programmes whichmake up the approaches to issues, and lead to the actions on the ground.Together they are the <strong>park</strong>’s best attempt to achieve the desired state specified inPart 1 above. Each subsection in this <strong>management</strong> <strong>plan</strong> is a summary of the particularprogramme, invariably supported by details in the appended Lower LevelProgrammes.The various programmes are classified into the five “real-world” activity groupingsas reflected in the <strong>SANParks</strong> biodiversity custodianship framework (Rogers 2003),namely Biodiversity and Heritage Conservation, Sustainable Tourism, Building Cooperation,Effective Park Management, and Corporate Support. Corporate<strong>SANParks</strong> policies provide the guiding principles for most of the subsections, andwill not be repeated here, except as references and occasionally key extracts.Within each of these groups, the last section entitled “Other Programmes” dealsunder one heading briefly with programmes which have relevance to MarakeleNational Park, but which have been deemed sufficiently small as to not requiretheir own subsection and reference to a fully-fledged lower-level <strong>plan</strong>.2.1 Biodiversity and Heritage Conservation2.1.1 Zonation ProgrammeThe primary objective of a <strong>park</strong> zoning <strong>plan</strong> is to establish a coherent spatial frameworkin and around a <strong>park</strong> to guide and co-ordinate conservation, tourism and visitorexperience initiatives. A zoning <strong>plan</strong> plays an important role in minimizing conflictsbetween different users of a <strong>park</strong> by separating potentially conflicting activitiessuch as game viewing and day-visitor picnic areas whilst ensuring that activitieswhich do not conflict with the <strong>park</strong>’s values and objectives (especially the conservationof the protected area’s natural systems and its biodiversity) can continuein appropriate areas.The zoning of Marakele National Park was based on an analysis and mapping ofthe sensitivity and value of a <strong>park</strong>’s biophysical, heritage and scenic resources; anassessment of the regional context; and an assessment of the <strong>park</strong>’s current and<strong>plan</strong>ned infrastructure and tourist routes/products; all interpreted in the context of<strong>park</strong> objectives.Overview of the use zones of Marakele National ParkThe summary of the use zoning <strong>plan</strong> for MarakeleNational Park is shown in Appendix 2 - Map 4. Fulldetails of the use zones (including high resolutionmaps), the activities and facilities allowed in each zone,the conservation objectives of each zone, the zoningprocess, the Park Interface Zones (detailing <strong>park</strong> interactionwith adjacent areas) and the underlying landscapeanalyses are included in Appendix 1: MarakeleNational Park Zoning Plan.Remote Zone: This is an area retaining an intrinsicallywild appearance and character, or capable of beingrestored to such and which is undeveloped and roadless.There are no permanent improvements or anyform of human habitation. It provides outstandingopportunities for solitude with awe inspiring naturalcharacteristics, with sight and sound of human habitationand activities barely discernable and at far distance.The conservation objectives for this zone requirethat deviation from a natural/pristine state should beminimized, and existing impacts should be reduced.The aesthetic/recreational objectives for the zone specifythat activities which impact on the intrinsically wildappearance and character of the area, or which impacton the wilderness characteristics of the area (solitude,remoteness, wildness, serenity, peace etc) will not betolerated. In Marakele NP, Remote areas were designatedin the rugged mountain areas in the centre and easternareas of the <strong>park</strong>. The zones were designated toinclude most landscapes with high environmental sensitivityand value.Primitive Zone: The prime characteristic of the zone isthe experience of wilderness qualities with access controlledin terms of numbers, frequency and size ofgroups. The zone shares the wilderness qualities of theRemote zone, but with limited access roads and thepotential for basic small-scale self-catering accommodationfacilities such as a bushcamp or small concessionlodges. Views of human activities and developmentoutside of the <strong>park</strong> may be visible from this zone. Theconservation objectives for this zone require that deviationfrom a natural/pristine state should be small andlimited to restricted impact footprints, and that existingimpacts should be reduced.The aesthetic/recreational objectives for the zone specifythat activities which impact on the intrinsically wildappearance and character of the area, or which impacton the wilderness characteristics of the area (solitude,remoteness, wildness, serenity, peace etc) should berestricted and impacts limited to the site of the facility.Ideally visitors should only be aware of the facility orinfrastructure that they are using, and this infrastructure/facilityshould be designed to fit in with the environmentwithin which it is located in order to avoid aestheticimpacts. In Marakele NP, Primitive areas weredesignated to buffer Remote areas from higher useareas and activities outside the <strong>park</strong>, as well as to protectmost of the remaining sensitive areas (such aslower mountains in the west and east) from high levelsof tourist activity. Almost all highly and moderately sensitiveenvironments that were not included within theRemote zone were included in this zone. Primitive areaswere also designated in valleys with relatively low environmentalsensitivity to allow access to Remote areas aswell as to contain the infrastructure required for <strong>management</strong>and tourist activity in these areas (e.g. trailhuts and access roads). The plains in the contractual<strong>park</strong> were designated Primitive, as the controlledaccess associated with Primitive is compatible with theactivities undertaken by the concessionaires. It is possiblethat these areas may be rezoned once the contractshave expired. In areas where Remote zones border onthe <strong>park</strong> boundary, a 100m wide Primitive zone wasdesignated to allow <strong>park</strong> <strong>management</strong> access tofences.Low Intensity Leisure Zone: The underlying characteristicof this zone is motorized self-drive access with thepossibility of small basic camps without facilities such asshops and restaurants. Facilities along roads are limitedto basic self-catering picnic sites with toilet facilities.This is the highest level of development and tourist usecurrently anticipated in Marakele NP. The conservationobjectives for this zone specify some deviation from anatural/pristine state is allowed, but care should betaken to restrict the development footprint.The aesthetic/recreational objectives for the zone specifythat activities which impact on the relatively naturalappearance and character of the area should berestricted, though the presence of larger numbers ofvisitors and the facilities they require, may impact onthe feeling of “wildness” found in this zone. LowIntensity Leisure areas were designated in the currentgame viewing area (Kwaggasvlakte), around currentaccommodation and other infrastructure, and in theareas around the <strong>plan</strong>ned new road network. Plainsareas with low environmental sensitivity south ofMarakele Pty Ltd were also included in this zone toallow for potential expansion of game viewing areasnorth of the mountains.The existing access road to the Sentech Towers wasinclude in the Low Intensity Leisure Zone despite it traversinghighly sensitive and valuable environments, as itis a key part of the <strong>park</strong>’s tourist infrastructure and theimpacts associated with its construction have alreadybeen incurred. The zoning along this road wasdesigned to preclude the possibility of expansion ofinfrastructure along this access road. A Low IntensityM A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N24 25

Leisure Zone was designated in the Vygeboomfontein area to accommodateexisting contractual obligations.Special Management Overlays of Marakele National ParkSpecial <strong>management</strong> overlays which designate specific areas of the <strong>park</strong> thatrequire special <strong>management</strong> interventions have not yet been identified inMarakele National Park.Overview of the Park Interface Zone of Marakele National ParkThe Park Interface Zones shows the areas within which landuse changes couldaffect a national Park. The zones, in combination with guidelines, serve as a basisfor a) identifying the focus areas in which <strong>park</strong> <strong>management</strong> and scientists shouldrespond to EIA’s, b) helping to identify the sort of impacts that would be importantat a particular site, and most importantly c) serving as the basis for integratinglong term protection of a national <strong>park</strong> into the spatial development <strong>plan</strong>s ofmunicipalities (SDF/IDP) and other local authorities. In terms of EIA response, thezones serve largely to raise red-flags and do not remove the need for carefully consideringthe exact impact of a proposed development. In particular, they do notaddress activities with broad regional aesthetic or biodiversity impacts.Marakele National Park has three Park Interface Zone categories. The first two aremutually exclusive, but the final visual/aesthetic category can overlay the others(Appendix 2 - Map 6).Priority Natural Areas: These are key areas for both pattern and process that arerequired for the long term persistence of biodiversity in and around the <strong>park</strong>. Thezone also includes areas identified for future <strong>park</strong> expansion. Inappropriate developmentand negative land-use changes should be opposed in this area.Developments and activities should be restricted to sites that are already transformed.Only developments that contribute to ensuring conservation friendly landuseshould be viewed favorably.Catchment Protection Areas: These are areas important for maintaining keyhydrological processes within the <strong>park</strong>. Inappropriate development (dam construction,loss of riparian vegetation etc.) should be opposed. Control of alien vegetation& soil erosion as well as appropriate land care should be promoted.Viewshed Protection Areas: These are areas where development is likely toimpact on the aesthetic quality of the visitor’s experience in a <strong>park</strong>. Within theseareas any development proposals should be carefullyscreened to ensure that they do not impact excessivelyon the aesthetics of the <strong>park</strong>. The areas identified areonly broadly indicative of sensitive areas, as at a finescale many areas within this zone would be perfectlysuited for development. In addition, major projects withlarge scale regional impacts may have to be consideredeven if they are outside the Viewshed Protection Zone.Current status and future improvementsThe current <strong>park</strong> use zonation is based on the same biodiversityand landscape analyses undertaken for aConservation Development Framework (CDF); howevercertain elements underlying the CDF such as a tourismmarket analysis are not yet fully incorporated into the<strong>park</strong> use zonation. A full CDF will be developed forMarakele National Park within the current update cycle.Remote areas will be investigated for possible formaldeclaration as Wilderness Area in terms of Section 22 ofthe PAA. Special <strong>management</strong> overlays which designatespecific areas of a <strong>park</strong> that require special <strong>management</strong>interventions (e.g. areas requiring rehabilitation) willalso be identified.This zonation is believed to support as best as possiblethe values and objectives in the desired state for this<strong>park</strong>. Once all components of a CDF are available, thezonation map will be revised and amended and shouldsupport Marakele’s desired state in an even morerefined and effective way.2.1.2 Water in the Landscape ProgrammeGuided by general <strong>SANParks</strong> principles in this regard(<strong>SANParks</strong> 2006), the key water in the landscape issuescomprise an interlinked water flow and river-riparianwetlandapproach in Marakele, focusing on:1. Ensuring mountain catchment function throughmaintenance of ecosystem processes in order toensure a continuous supply of good quality water tosurrounding environments and downstream users.Focus will need to be placed on collation and evaluationof DWAF flow and quality data and utilisationof this data to set first stab TPCs for Marakele’s contributionto the delivery of these ecosystem goodsand services. Thereafter ongoing monitoring andevaluation will be required.2. Evaluation, monitoring and <strong>management</strong> of potentiallysensitive wetland areas (sensitive to fire andherbivore <strong>management</strong> regimes in particular) andpotentially sensitive riparian areas (particularly toelephant impacts) will require careful integration ofhabitat, animal impact and vegetation monitoringprogrammes.3. Rehabilitation of damaged or redundant structuresimpacting flow and other ecosystem processes. Thiswill firstly require an inventorisation of all wetlands,rivers, dams, waterholes and boreholes and anassessment and prioritisation for phased removal ofman-made structures impacting negatively on thesystem. In conjunction with the herbivory programme,it is likely that certain dams will be prioritisedfor rehabilitation. Cognisance will need to betaken of exotic fish within these systems which havethe ability to severely impact aquatic ecosystemhealth and functioning.These three focus areas will consume much of ourenergy and will demand an integration of researchand monitoring efforts to support the desired state ofMarakele (lower level <strong>plan</strong> detailed in SupportingDocument 3).2.1.3 Fire ProgrammeThe natural frequency of lightning-induced fires inMarakele results in sections of the <strong>park</strong> burning almostevery second year, normally at the end of Septemberjust before the rains. Fire should thus be managed in themountainous sourveld areas of the <strong>park</strong> with a natural,lightning-induced ‘laissez faire’ approach. Low-lyingsweetveld areas should be burnt by point ignitions setby <strong>management</strong> early in the fire season (April – June) tosimulate natural ignition sources. This will have theeffect of breaking up fuel loads and forming a patchmosaic, hypothesised to maximise biodiversity.However, this system will need to be applied in a flexiblemanner, able to adapt to annual variations in climaticconditions and biomass production.Certain vegetation types within Marakele are thought tobe fire-sensitive. This includes the Widdringtonia community,the vlei areas, as well as the forest in mountaingorges. At this stage we do not recommend that fire isspecifically kept out of such areas. Rather, it must firstbe determined whether these vegetation communitiesare truly fire sensitive or whether fire merely hamperstheir growth and that in areas were fire is infrequent,these vegetation communities have flourished. If thecommunities are proven fire sensitive, fire <strong>management</strong>for these areas will be revised. In the interim, cooler,lower intensity fires (early in the fire season) should be setin these areas and fire should not be actively kept out.Fire as a tool to assist with the control of bush thickeningor encroachment should be considered on certainareas on Kwaggasvlakte. We propose thatDichrostachys cinerea encroached areas are strategicallyselected, targeted and monitored for effectiveness ofthe fire <strong>management</strong> approach. This will entail applicationof cool summer low intensity fires after an initial hotfire application to cause maximum topkill when fuelloads are highest in September / October just beforethe spring rains.M A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N26 27

Fire safety issues will need to be addressed through appropriate and effective firebreakswhich should be burnt in the beginning of winter, to a minimum width of 5meters and burnt at night. However, exact standards will need to be agreed uponthrough the upcoming Fire Protection Association rules and regulations. Marakelewill need to make a concerted effort to establish or become a member of a FireProtection Association to assist in achieving fire safety and security aims for the<strong>park</strong> and neighbouring areas. Details of all these aspects are provided in the lowerlevel <strong>plan</strong> (Supporting Document 4).2.1.4 Herbivory Programme, including Elephant ManagementThis follows the general guidance of <strong>SANParks</strong>’s corporate herbivory policy as wellas that related to the provision of artificial water for herbivores. Likewise, introductionof herbivores and predators is governed by central policy (<strong>SANParks</strong> 2006).The inherent vegetation and topographic heterogeneity of this <strong>park</strong> has positivespin-offs for floral and faunal species richness and biodiversity and Marakele has awide diversity of large mammal species after numerous reintroduction efforts.The challenge lies in managing a complex mosaic of sweet, mixed and sourbushveld types in a relatively small <strong>park</strong> under various scenarios of herbivore use.Utilisation of the landscape by especially larger herbivores such as elephant mayresult in significant changes to the vegetation, particularly certain <strong>plan</strong>t communitiessuch as ‘tall closed woodland’, ‘short closed woodland’ and the ‘termitariumthickets’. The nutrient-rich low-lying areas are likely to develop natural hotspots ofhigh utilisation, requiring monitoring as these areas are likely to indicate when herbivorenumbers are reaching levels where their impact may be exceeding thethreshold of concern. The mountain areas represent more unique vegetation typesin South Africa, and although not heavily utilised by herbivores, are more sensitiveto their impacts. TPCs in these areas thus differ substantially form those set for theplains areas (see Supporting Document 5).While impacts of medium- and smaller-sized herbivores will likely be regulated bypredation, rainfall and associated availability of herbaceous material and browse,these factors are unlikely to control larger herbivores such as rhino and elephantwhich are likely to require more active <strong>management</strong>. Herbivore impacts will bemeasured by the stated TPCs and adaptive <strong>management</strong> and ecosystem flux simulationapplied where possible. It must be noted that elephant numbers in Marakelemay increase substantially over a short time when the fence between Marakele andWelgevonden Private Game Reserve is removed in future, which is expected toresult in an influx of elephants. The ultimate decision regarding the <strong>management</strong> ofelephant will depend heavily on the finalisation of theDEAT norms and standards for elephant <strong>management</strong>and the outcomes of the Elephant Assessment but froma practical point of view, it will be difficult, if possible atall, to restrict elephants only to certain areas of the <strong>park</strong>or to exclude them from others.Due to the extensive drainage system bisectingMarakele, artificial water provision is not necessary andis not encouraged and should revert to the initial naturaldistribution of water. Any establishment of artificialwater points in the sweetveld areas must be well consideredand restricted. The animal impacts to wetlands inthe mountainous areas need to be monitored to avoidexcessive trampling of the vegetation and compactionof the soil. Fences should only be considered as anoption to exclude animals from certain very sensitiveand unique areas, but this can only be used in practicefor very small vegetation communities, more as aresearch than <strong>management</strong> tool.Future research must focus on herbivory in the contextof the topographical variability of the <strong>park</strong> and theresponse of different feeder classes to seasonal changesin order to fulfill their nutrient requirements. The interactionsbetween herbivores and <strong>plan</strong>ts at various spatialand temporal scales and the resultant outcomes haveimportant and far-reaching implications for <strong>management</strong>.Monitoring efforts must focus on vegetation,large animals (aerial surveys and dung counts), smallervertebrates and invertebrates, degradation, backgroundclimatic information.The highest risk to achieving a successful effective herbivore<strong>plan</strong> is posed by a possible collapse in collaborationand co-operation between various stakeholders.Mutual agreements and open communication channelsare vital and will have to be fostered continuously iflong-term success in co-operative <strong>management</strong> is to bemaintained. Predation is an added challenge requiringattention. Marakele is currently not in a position to supportlarge numbers of carnivores on a sustainable basis.In the meantime, contractually introduced carnivoresmust be monitored and may require more intensive<strong>management</strong>.Further introduction or augmentation of species must infuture be critically evaluated against the desired stateand the opportunity costs of <strong>management</strong> concentratingon non-core objectives must be minimised if thecore objectives are to be met.2.1.5 Predator Management ProgrammeCheetah, wild dog, lion and spotted hyena have beenreintroduced to Marakele National Park in the past, themain objectives having been to (a) enhance biodiversity,specifically by introducing predation as an importantecological process; (b) improve the ecotourism value ofthe area, and (c) improve a species’ conservation statusby contributing to metapopulation strategies of globallyendangered species.<strong>SANParks</strong> is contractually bound and thus currently haslegal obligations to provide for a ‘big five’ experience(which specifically includes lion) for the Marakele ParkPty (Ltd) contractual partners, as well as to their currentconcession holders. These legally binding agreementsmust be balanced with the desired state of the <strong>park</strong>,which has been set with wider stakeholder inputsaccording to the best-practice adaptive <strong>plan</strong>ning frameworkfor protected area <strong>plan</strong>ning.The decision to temporarily remove wild dog fromMarakele (made in 2007) due to high risk and legal ramificationsof frequent breakout events will be re-evaluatedwithin the next 5-year cycle, particularly since<strong>SANParks</strong> has committed to the metapopulation <strong>management</strong>approach for this globally threatened species.Lion, in particular, are a charismatic predator, valued fortheir contribution to tourist experience as it is currentlymarketed, particularly by the contractual partners.However, lion are also considered a high risk specieswith large range requirements, potentially rapid populationgrowth and significant impacts on prey populations(which are also an important element of the wildlifetourism experience).For this species particularly, targeted research and monitoringneeds to be undertaken in collaboration withpartners and neighbours (particularly WelgevondenPrivate Nature Reserve) and thresholds of potential concernset as a matter of priority, in order to track andmanage their impacts (both ecological and socio-political)within predetermined acceptable flux limits that arejointly agreed upon by stakeholders as supporting thedesired state of Marakele. This must be addressed as amatter of urgency within the next 5 years. Importantly inthis regard, Marakele will be able to contribute to thewider debate around extent to which natural processescan take place without intervention in medium-sized<strong>park</strong>s (see Supporting Document 6).2.1.6 Disease Management ProgrammeMarakele has a prolific diversity of indigenous vectorbornand viral diseases and the major <strong>management</strong>challenge is to prevent exotic disease introduction tothe <strong>park</strong>, particularly related to buffalo introductions(see Supporting Document 7). Currently the buffalo inMarakele are testing positive for a Theileria species andongoing tests are being conducted to confirm its typeand origin. Nevertheless, the Department of Agriculturehas sufficient evidence to suggest that this is T. parva,the cause of theileriosis. Marakele has thus been issueswith a quarantine notice and all buffalo will need to beremoved from this national <strong>park</strong> within the next months,as feasibility dictates. After the quarantine period,ongoing monitoring of reintroduced animals will beM A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N28 29

equired and any buffalo to be introduced in future must be rigorously tested toprevent buffalo-associated diseases from accidentally being introduced to the<strong>park</strong>. Further resources will also be required to test the buffalo occasionally tokeep track of their disease status. Fence maintenance, to the standard wherebreak-outs of species like buffalo are prevented, is essential.Anthrax may occur in the <strong>park</strong> and encouragement for standard vaccination forthis disease in domestic stock will significantly reduce any risk of possible diseasetransmission between the <strong>park</strong> and domestic stock in the surrounding area. Rabiesand distemper can pose a threat to carnivores in particular in Marakele so vigilanceand communication will be required regarding the status of these diseases surroundingthe <strong>park</strong>. Apart from the uncertainty of the Theileria status of the buffaloin the <strong>park</strong>, no major disease threat is present from the <strong>park</strong> to neighbouringcommunities.Prevention of disease introduction and active surveillance (through adequate passivesurveillance) of any disease event must be undertaken by <strong>management</strong> inMarakele National Park.2.1.7 Pollination ProgrammeMarakele, with its high diversity of vegetation types and rare and threatened <strong>plan</strong>tspecies, requires an understanding of the sustainability of pollination systems toensure that the biodiversity aspects of the desired state can be met in the longterm. In particular, dioecious species such as Podocarpus latifolius andEncephalartos species might be at risk due to potential imbalances and dispersalof the sexes due to anthropogenic influences (including poaching and over-utilisationof these <strong>plan</strong>ts). Currently, this programme (Appendix 8) focuses mainly onresearch and understanding of pollination systems for important and vulnerable<strong>plan</strong>ts and their pollinators.2.1.8 Invasive Alien Biota ProgrammeThe principles concerning this are well-established in <strong>SANParks</strong> (<strong>SANParks</strong> 2006)and Working for Water, whose co-operation plays a critical role in the control ofalien <strong>plan</strong>ts in Marakele.The invasion of Marakele by alien species is fortunately relatively limited in comparisonwith some other national <strong>park</strong>s, however, continued vigilance and sustained<strong>management</strong> are required to maintain the current status. Main threats arefrom invasions of black wood, queen of the night, lantana, guava, bramble andlarge-mouth bass (more detail is provided in Appendix 9).The <strong>SANParks</strong> Invasive Species Control Unit (ISCU), actingas the implementing agent of the Working for Waterproject in <strong>SANParks</strong>, has largely been responsible forthe control of alien <strong>plan</strong>ts in Marakele. The ISCU hasdelineated 97 treatment areas for alien <strong>plan</strong>t controlacross Marakele. Of these most are at various stages offollow-up treatment, with the rest <strong>plan</strong>ned for initialcontrol operations in the coming years. In addition, <strong>park</strong>rangers as well as <strong>SANParks</strong> Honorary Rangers havebeen involved in and continue to support Marakele inthe control of alien <strong>plan</strong>ts at former homesteads andabandoned infrastructure. In the case of the alien mammals,birds and fish, an assessment is needed to determinethe current or potential biodiversity impacts ofeach. Following this, <strong>management</strong> actions must be prioritisedand implemented where necessary and feasible.A system of TPCs as well as objectives for invasivespecies research, <strong>management</strong> and awareness(Supporting Document 1, Figure 3 a & b; SupportingDocument 9) has been established in Marakele and thiswill contribute to meeting the desired state of this <strong>park</strong>.2.1.9 Species of Special Concern ProgrammeThe <strong>SANParks</strong> approach for prioritising species of specialconcern, which then require appropriate monitoringand TPCs, emphasises native South African and national<strong>park</strong> species which are globally critically endangeredor endangered. In the Marakele context (SupportingDocument 10) these species are currently recogised asblack rhino (Diceros bicornis) [and wild dog (Lycaon pictus),although these have been removed from the <strong>park</strong>at this stage]. TPCs and monitoring for black rhino arespecified. Regional metapopulation <strong>management</strong>strategies in which <strong>SANParks</strong> is involved may necessitateconsideration of inclusion of such species in our<strong>plan</strong>ning, if compatible with existing major <strong>park</strong> objectives.Although no <strong>plan</strong>t or small vertebrate species inMarakele are classified as globally critically endangeredor endangered, the Waterberg cycad, Encephalartoseugene-maraisii, is listed as vulnerable and should bemonitored due to threat from illegal harvesting activities.Similarly there are a number of vulnerable birds andreptiles, as well as the pangolin, but no structured programmesare developed for these. General biodiversitysurveys will be required in Marakele to refine specieslists, especially for small vertebrates and invertebratesto further assess this programme.2.1.10 Park Expansion ProgrammePark expansion is governed by <strong>SANParks</strong> principles andpolicies and the expansion of Marakele remains importantfor <strong>SANParks</strong> in its attempt to establish an ecologicallyviable protected area in the western WaterbergMountain catchment area (Supporting Document 11).The objective is to create a <strong>park</strong> that primarily conservesthe Waterberg bushveld landscape, with its associatedecological patterns and processes through a mosaic ofcooperation agreements and public-private partnerships.Initial visions were for a 3 000 km 2 protected area,but a systematic conservation initiative identified anarea of 1 784 km 2 in line with an even larger WaterbergBiosphere Reserve. The desired state identified throughthe systematic conservation <strong>plan</strong>ning process attemptsto consolidate an ecologically viable <strong>park</strong> around theMatlabas-Mamba River catchment through cooperativeconservation agreements; protect the importantWaterberg altitudinal diversity; and provide a viableeco-tourism product as part of the economic engine forthe region, particularly in the light of fading iron oremining and agricultural activities.The current 67 800 ha large <strong>park</strong> (52 074 ha state ownedand 15 753 ha Marakele Pty Ltd contractually includedprivate land) conserves three different vegetation typeswhile the desired state for the <strong>park</strong> would see the additionof another vegetation type (the central sandybushveld) to the <strong>park</strong>. This greater <strong>park</strong> will include, by<strong>management</strong> arrangement, the 330 km 2WelgevondenPrivate Game Reserve, 90 km 2Matla Mamba GameReserve, the 40 km 2 Sterkfontein and 20 km 2 Hoopdalsections. However, towards meeting this larger <strong>park</strong> anumber of short-term priority consolidation areas for<strong>SANParks</strong> have been identified, including a western andsouthern block which could be included via either contractualor acquisition means. In addition, <strong>SANParks</strong>need to consider the buy-back of current contractualland.The expansion of the <strong>park</strong> falls in line with the nationalstrategic objective (SO 5) in the NBSAP (2005) ofexpanding the national protected area towards 12% ofthe terrestrial and 20% of the coastal environment.2.1.11 Rehabilitation ProgrammeWidespread rehabilitation is taking place in the <strong>park</strong>using principles contained in an overall rehabilitationframework (<strong>SANParks</strong> 2006). Marakele is still in a phaseof expansion and most, if not all the properties purchased,were previously used for farming operationsand <strong>park</strong> <strong>management</strong> endeavours to reverse the negativeimpacts caused by historical agricultural land use byidentifying and rehabilitating areas in a structured andprioritised manner to support biodiversity and wildernessgoals. The most important areas to be restored orrehabilitated within Marakele are the terrestrial fieldlayer (relatively limited unnatural erosion, but extensivebush encroachment or bush thickening and old croppinglands), redundant infrastructure (primarily old roadsand 4x4 tracks as well as gravel/borrow pits, bushcamps, old farm buildings and old metal fence postsand fencing), and aquatic systems (mainly catchmentM A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N30 31

dams). The main <strong>management</strong> objectives and actions should be implemented asfar as financially and practically possible, namely rehabilitation of the terrestrialfield layer to restore the physical and aesthetic nature of Marakele to an acceptablestate, removal of all redundant man-made structures and items, and, wherenecessary, stabilisation and restoration of the hydrological processes to an acceptablelevel. These efforts will support longer-term achievement of the desired statefor this <strong>park</strong>. The main risks lie with insufficient funding and a lack of staff to follow-up<strong>management</strong> and monitoring of the rehabilitation and restoration efforts.Details are provided in Supporting Document 12.2.1.12 Cultural Resource ProgrammeThis programme (Appendix 13) is advised by <strong>SANParks</strong> policy on cultural resource<strong>management</strong>. During 2001-2002 a heritage inventory and Cultural HeritageManagement Plan were developed for Marakele National Park and adjacent properties,identifying 130 tangible heritage sites, including Stone Age surface scatters,historic cemeteries, historic farmsteads and outbuildings as well as Early andLate Iron Age sites. Intangible resources were also documented, including traditionaland medicinal uses of <strong>plan</strong>ts. Evaluations of the significance, conservationstatus and utilisation options of all the heritage resources were accompanied bydetailed recommendations for <strong>plan</strong> implementation. Specific heritage resourceobjectives for the <strong>park</strong> in the next 5-10 years include further development andupdating of the heritage inventory, implementation of the Cultural HeritageManagement Plan and development of appropriate Heritage Site ManagementPlans for those sites that have been identified for educational, research and/ortourism purposes (Supporting Document 13).2.1.13 Other Programmes under Biodiversity and Heritage ConservationSmaller issues in Marakele National Park include problem animal <strong>management</strong>(Supporting Document 14), and natural resource utilisation. Currently there are nocommunity-based resource use projects within the <strong>park</strong>. Both of these enjoy guidancefrom <strong>SANParks</strong>’ corporate principles.2.2 Sustainable TourismThis heading clearly also cross-links to the ZonationProgramme provided in 2.1.1. as well as to the CDF,once completed. The tourism lower level <strong>plan</strong> is outlinedin Supporting Document 15.2.2.1 Sustainable Tourism ProgrammeThe <strong>park</strong> lies some 250 km north of Johannesburg,near Thabazimbi with Tlopi Tented and ModikelaCamps, Bontle Camping Site and the day visitors’ area,which can be accessed by normal sedan car. In total, the<strong>park</strong> can accommodate 260 people per night. The averagebed nights sold for the <strong>park</strong> is 45.8% and averageunit nights sold is 50.66%. This is considered good inthis relatively new <strong>park</strong>. This <strong>park</strong>’s proximity toGauteng should give it a competitive advantage,although most of its visitors at this stage are day visitors.Currently, the <strong>park</strong> offers self-guided drives, a 4x4route, bird watching, day walks and game drives. The<strong>park</strong> has a linked road network of 38 km, although thiswill change towards May 2007, after the completion ofthe newly developed internal roads and entrance to the<strong>park</strong>. Marakele is currently still divided into two parts(namely Kwaggasvlakte section and the greaterMarakele National Park) by a public gravel road, theHoopdal Road.Strengths of Marakele include the wilderness experience,the large number of game farms in the area thatprovide a source of day visitors, the new Tlopi TentedCamp, the world’s largest breeding colony of Cape vulturesand the <strong>park</strong> being a well known 4x4 destination.The <strong>park</strong> is well situated to capitalise on the Gautengmarket. There are a number of opportunities for naturebasedactivities, such as guided wilderness trails, abseilingand horse safaris as well as the development ofbirding packages. Nevertheless, there are a number ofsignificant weaknesses and threats, including the poorroad network, deteriorating during the rainy season, ashortage of activities for tourists visiting the <strong>park</strong>, limitedaccess to certain “prime” game-viewing areas of the<strong>park</strong> (real or perceived) due to contractual and concessionagreements, restricted development options dueto terrain, limited marketing, staff shortages, a need fortraining and unreliable telephone connections affectingservice (e.g. RoomSeeker and credit card machines).The local IDP indicates that tourism in the area is welldeveloped although it is poorly marketed. Proposedregional strategies to improve tourism to the areainclude upgrading of roads linking to MarakeleNational Park, development of a tourism centre, moreeffective marketing, a tourism office in the Thabazimbimunicipal building, upgrading the airfield and website.A gap analysis indicates that there is a need for moreaccommodation, more tourist activities, such as hikingtrails, wilderness trails and guided game drives, providingmore tourist facilities, such as picnic areas and hidesat water holes, a day visitor area with braai facilities andswimming pool, an environmental education centre,staff training and better marketing of the <strong>park</strong>/cluster.Nevertheless, all these options must be considered andweighed up against the desired state of the <strong>park</strong>,including its zonation, and the important objective ofgenerating and applying a development and economicmodel to Marakele that is appropriate to its biodiversitycharacteristics, wilderness character and is explicit ofthe distribution of costs and benefits within and acrossvarious cooperative arrangements (see SupportingDocument 1). It is only in doing this that Marakele canstrive to fulfil both its <strong>park</strong> mission as well as the broadervision developed jointly for the cooperative governancespectrum. This will require intensive and dedicatedeffort in the near and medium-term future, and <strong>park</strong><strong>management</strong> and <strong>SANParks</strong> will need to be ever-mindfulof this pressing need.Commercial and Community activities: Marakele PtyLtd has two commercial lodges on the contractual land,namely Marataba concession and Kubu lodge (still at itsdevelopmental stage). Commercial DevelopmentDivision to provide the mechanisms in place to monitorimpact of these commercial activities. However, wehave also had the discussions with the owners of a farmto the west of the railway. With regards to these discussionsit should be noted that potential commercialactivities are evaluated on a continuous basis (some ofthese might be closely linked to <strong>park</strong> expansion).However, the Strategic Plan for Commercialisation(SPfC) which is an approved <strong>SANParks</strong> strategy documentis used to prioritise commercial projects. In addition,the process that is followed to initialize such projectsfollows the National Treasury approved toolkit.There are currently no written agreements for use ofnatural resources by local communities.2.3 Building Co-operationTransparent, trusting co-operative, collaborative andmutually beneficial relationships with the broader <strong>park</strong>community are essential to the sustainability ofMarakele National Park (see sections 1.1.3 and 1.2 aswell as Supporting Document 1). The <strong>park</strong> will have tomaintain existing, and identify and implement newopportunities for sustaining new relationships betweenitself and surrounding communities and broader <strong>park</strong>users. Similarly, co-operative relationships need to beestablished and nurtured with all spheres of governmentand other stakeholders to ensure that regional initiativesand developments contribute to, not compromise,the attainment of the overall desired state andobjectives for this <strong>park</strong>. Three key People andConservation programmes will run from Marakele duringthe next 5 year period, detailed below.M A R A K E L E N A T I O N A L P A R K • P A R K M A N A G E M E N T P L A N32 33