Turkey - mutual learning programme

Turkey - mutual learning programme

Turkey - mutual learning programme

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

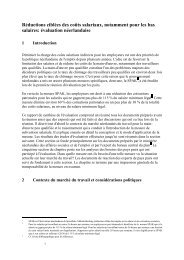

TURKEYTable 1.1.b. Labour Market Informality, Percentage of Unregistered Employment2000 2002 2005 2006 50Agriculture 88,6 90,1 88,2 88,5Wage and Salary Earner 18,3 36,7 52,5 51,4Daily Waged 94,0 98,8 98,3 97,9Employer 67,9 70,9 72,2 77,3Self-Employed 80,0 78,4 78,6 78,0Unpaid Family Worker 96,2 99,7 97,9 97,8Non-Agriculture 29,2 31,7 34,2 34,7Wage and Salary Earner 14,8 19,4 22,7 23,2Daily Waged 78,8 87,1 90,1 91,3Employer 11,2 15,2 21,3 21,6Self-Employed 41,3 44,6 50,3 52,1Unpaid Family Worker 74,7 87,2 80,2 82,1TOTAL 50,6 52,1 50,1 50,5Source: Own calculations from TURKSTAT, Household Labour Force Surveys, various years.1.2 Trends in UnemploymentThough unemployment rate was almost below 10 percent throughout 1990s, the last crisis led toa significant increase particularly in the urban areas which has steadily been around the samelevel above 10 percent since then. The existence of informal employment opportunities has keptthis increase significant but relatively incremental. Regarding other structural aspects ofunemployment, one should consider the increase in not only the long-term unemployment ratefrom 1.4 % in 2000 to 4% in 2004 but also the share of long-term unemployed in the totalunemployment from 22 % in 2000 to 39% in 2004 where a significant gap between male andfemale unemployment is also evident. In terms of the youth unemployment (for the age group 15-24), there has been a slight decrease since 2003 from 20.5% to 19% while educationalattainment still cannot fully account for granting access to employment for younger cohorts due tonot only lack of appropriate job opportunities but also certain inadequacy of the educationalqualifications for the jobs available in the market.1.3 Legal Framework: New Labour CodeIn order to complete the background regarding the labour market in <strong>Turkey</strong>, legislative frameworkshould briefly be reviewed with a view to highlight the employment protection with specificreference to the types of contracts in practice. For the sake of simplicity, employment protectionlegislation covering kinds of contracts permitted will be reviewed.Being highly controversial in the preparation stage, the 2003 reform of the Labour Code has beennecessitated by the inability of the previous piece of legislation to the contemporarytransformation of work and the industrial relations. During the preparation of the draft by the50 Data refers to 3rd quarter of 200616-17 November 2006 Peer Review Incentives for indefinite employment, Madrid99

TURKEYemployment where almost all these costs were not incurred. In sum, one can argue thatlegislative framework tends to create a duality in the labour market in <strong>Turkey</strong>: stability of existingjobs are increased at the expense of less opportunities for regular employment in the formalsector as well as more longer-term unemployment and non-participation of the labour force. Alsoincreasing vulnerability of certain groups such as women and youth who are less likely to find“good, stable” jobs tend to push them out of the formal segment either into the informal part or outof the labour market.2. Potential Transferability of the Policy MeasureThe policy measure discussed in Toharia (2006) mainly aims to curb the extent of temporary workby introducing “employment-promotion open-ended contract” with lower severance payments andallowing for lower social security contributions paid by employers. Potential implementation in<strong>Turkey</strong> would be viewed in light of the following observations:• In the new Labour Code in <strong>Turkey</strong>, fixed-term employment contracts are only allowed forcertain cases. In other words, definition of valid reasons for contracting fixed termemployment where the nature of the assignment assumes an end date such as being eitherseasonal, for a specific project or to replace an absent worker implies that in <strong>Turkey</strong> use offixed-term contracts are restricted.• Again, as stated in the Article 11, unless there are objective substantial reasons justifying therenewal of such contracts, fixed-term labour contracts are assumed to be non-renewablewhich mainly aims to prevent use of successive fixed-term contracts. In case of a renewal,Article 11 also states that fixed-term contract shall be classified as an open-ended labourcontract.When these two observations are considered, it seems to be the case that all short-comings havealready been foreseen, legislative measures were defined while the framework seems relativelyrestrictive. Apparently, a less restrictive framework where the use of fixed-term contracting wouldbe extended could be risky in terms of encouraging employers to use this form of employment toavoid the obligations of permanent contracts as the current Code aimed to prevent. On the otherhand, considering the labour market situation in <strong>Turkey</strong>, such loosening may cater for shiftingworkers who are in casual employment (without contract) into more formal contractedemployment relations. To put it one step further, when coupled with a moderation of severancepay requirements, permanent contracts in long-term employment would not be avoided (as it isthe case for now) and formalization of casual employment could significantly be evident.Actually, as mentioned in World Bank (2006), pools of workers in fixed-term or temporaryemployment and uncontracted casual employment are almost similar where women, young andold worker and poorly educated are overrepresented. This similarity suggests that these twotypes of employment relations can be regarded as substitutable to some extent as the significantdifference between these two groups in terms of formal social security coverage must beconsidered. That is to say almost half of the fixed-term workers are covered by one of the socialsecurity plans while the corresponding figure is only 8.8 percent of casual workers (HouseholdLabour Force Survey 2002 cited in World Bank 2006). Thus, a less restrictive fixed-termcontracting would transform at least some of casual employment relations into more formalcontracted ones for the case of Turkish labour market.16-17 November 2006 Peer Review Incentives for indefinite employment, Madrid101

TURKEYRegarding the social security contribution reduction aspect of the incentive policy in Spain, someinference can be made for implementation in <strong>Turkey</strong>: among the root causes of the highincidence of informality in the labour market in <strong>Turkey</strong>, one can argue for relatively high costs ofemployment to be borne by the employer. For this reason, reductions in the social securitycontribution would serve for some kind of formalization of certain casual-informal employmentrelations. However, considering extent of the pools of workers mentioned above as well as thelow level of labour force participation, such an incentive in form of reductions should carefully bedesigned especially in terms of targeting the vulnerable groups in the labour market.As for the financing of the incentives through unemployment insurance fund, the generalagreement among social partners in Spain seems as if the issue has not been debated as acontroversy. For the case of <strong>Turkey</strong> it’s worthwhile to note that the legislation regardingUnemployment Insurance is quite restrictive in terms of eligibility conditions as well as coveragethough a significant amount of surplus has already been accumulated. There is a contemporarydebate, which has not been resolved yet, about reforming the current legislation by extending theeligibility conditions and duration of payment of benefits to cover more of the formally registeredlabour force and use of surplus of the Fund which consists of premiums jointly paid by theemployer, employee and state (3 percent, 2 percent and 2 percent of gross wage, respectively).In a nutshell, one can argue that contemporary labour market in <strong>Turkey</strong> has certain drawbacksthat hinder the discussion of the policy transfer. Formal-informal dualities, legislative rigidities,jobless growth, low levels of participation should all be separately analysed and considered inassessment of potential implementation regarding all aspects of policy either financing, coverageor evaluation. As also mentioned by the Spanish trade union representatives that have signed the2006 Agreement, peculiar nature of the social dialogue in Spain has also contributed to theconsensus between all social partners. In this regard, the potential transferability of the policymeasure remains highly limited since it remains as a by-product of the country-specific context.3. Contemporary Debates in <strong>Turkey</strong>Not to replicate the above mentioned debates, here one must also consider labour market reformdebate in <strong>Turkey</strong> which has been grounded on the “employment creation” in relation to the recentexperience of growth without jobs. Apparently, it should be noted that any design for reform forencouraging job creation should consider certain measures to ensure protection of workerbesides protection of the job. For instance, while enhancing flexibility in the labour market, currentsegmented structure should be considered so as to be complemented by measures in the form ofenhanced social protection. Lacking such mainstreaming in the policies, current debates remainmarginal as they address solely certain features. When analysed in detail, new Labour Code in<strong>Turkey</strong> has introduced a certain level of flexibility in terms of employment protection legislation.However, debates on flexibility have constantly been locked in numerical flexibility 55 , externallabour market flexibility 56 and wage flexibility aspects due to short term concerns. As this ishindering a more holistic approach, enhancing improvements in safety nets through not only a55 Often in terms of flexibility of time, through the use of atypical employment types or engaging in subcontractingpractices.56 Especially by the introduction of new types of contracts in the new Labour Code.16-17 November 2006 Peer Review Incentives for indefinite employment, Madrid102

TURKEYredesign of unemployment insurance legislation but also contributing to establishment of a propersocial protection system that would serve to avoid strengthening the existing segmentation orduality in the labour market is needed. In this regard, it must be noted that recently introducedproject (by Ministry of Labour and Social Security) on combating informal employment should in away be transformed into a coherent policy with the support and participation of all social partnersconsidering the essential role of social dialogue in the Spanish case. All in all, flexicurity for theTurkish case must be treated in caution so as to be discussed within a holistic policymainstreaming approach.ReferencesSural, N. (2005) “Employment Termination and Job Security Under New Labour Act”, MiddleEastern Studies, vol. 41(2), pp.249-268.Toharia, L (2006) “Incentives to Indefinite Contracts in Spain”. Discussion paper prepared for thePeer Review Meeting, Spain.World Bank (2006) <strong>Turkey</strong>: Labour Market Study. Document of the World Bank. ReportNo.33254.www.tuik.gov.tr16-17 November 2006 Peer Review Incentives for indefinite employment, Madrid103