Predictable, Preventable - Canadian Red Cross

Predictable, Preventable - Canadian Red Cross

Predictable, Preventable - Canadian Red Cross

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

2 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 3Strategy 2020 voices the collective determination ofthe International Federation of <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> and <strong>Red</strong>Crescent Societies (IFRC) to move forward in tacklingthe major challenges that confront humanity in the nextdecade. Informed by the needs and vulnerabilities of thediverse communities with whom we work, as well as thebasic rights and freedoms to which all are entitled, thisstrategy seeks to benefit all who look to <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> <strong>Red</strong>Crescent to help to build a more humane, dignified andpeaceful world.Over the next ten years, the collective focus of theInternational Federation will be on achieving thefollowing strategic aims:1. Save lives, protect livelihoods, and strengthenrecovery from disasters and crises2. Enable healthy and safe living3. Promote social inclusion and a cultureof non-violence and peaceISBN 978-1-55104-540-5© 2012 <strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong><strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>Founded 1896 Incorporated 1909The <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> emblem and designation “<strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>” are reserved in Canada by lawfor the exclusive use of The <strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> Society and for the medical unitsof the armed forces by the Geneva Conventions Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. G-3.The programs of the <strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> are made possible by the voluntaryservices and financial support of <strong>Canadian</strong>s.AcknowledgmentsWe would like to gratefully acknowledge the following people who contributedtheir expertise, time, and lived experiences to this report:Contributors: Maria Elisa Alvarado, Director General of the Honduran<strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>; Dr. Michaële Amédée Gédéon, President of the Haitian <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>;Ange Sawh, Cindy Fuchs, and Louise Geoffrion, Disaster Management Team,<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>; Jan Gelfand, Director of Operations, International Federationof <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> and <strong>Red</strong> Crescent Societies, Americas Zone.Authors: Gurvinder Singh with Melinda Wells and Judi FairholmLayout and Design: Sharonya Sekhar, design editor; Molly Baker, designerResearch Support: Tan Bokhari; Reem GirgrahReviewers:<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>: Pamela Aung Thin, Jessica Cadesky, Hossam Elsharkawi,Cindy Fuchs, Richard McCabe, Rachel Meagher, Sharonya Sekhar, Louis PhilippeVezina, Valerie Whiting, Pamela Davie, Christine BlochInternational Federation of <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> and <strong>Red</strong> Crescent Societies:Siddharth Chatterjee, Aradhna Duggal Jonathon Gurry, Sandra Gutierrez,Juliet Kerr, Lisa SoderlindhInternational Committee of the <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>: Jose Antonio Delgado, Markus GeisserThe Brookings Institution: Elizabeth FerrisIndependent Experts: Elaine EnarsonFront COver: benoit matsha-carpentier, ifrcBack COver: ifrchector emanuel, american RED crossTABLE OF CONTENTSPreface..........................................................................4Overview........................................................................6A <strong>Predictable</strong> Problem..............................................8Why Violence Escalates in Disasters..................10Profile: Honduras....................................................12Profile: Haiti...............................................................16The Consequences of Complacency....................19Barriers to Taking Action.......................................19Using a Public Health Approach...........................20Profile: Canada.........................................................22Best Practices for Action.......................................24PROFILE: International Federation,Americas Zone............................................................28Conclusion.................................................................32Resources...................................................................33

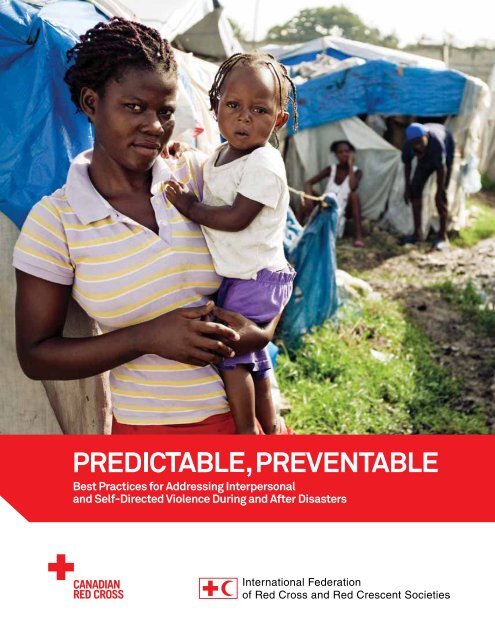

4 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 5PREFACEIn our world, disasters continue to disrupt and damage landscapes and human lives.Often in the aftermath, people unite spontaneously with compassion and generosity.Despite personal trials, people of all ages volunteer to help those who are ailing, communitiescome together and countless acts of remarkable humanity take place. Yet, assurvivors regain their footing, seek shelter and livelihoods, and try to rebuild, they facemany hurdles. Among these, but often unspoken and secret, is the devastation causedby the violence that can follow disasters. People’s safety and security become underminednot only by the disaster but also by violence in the forms of abuse, exploitation,harassment, discrimination and rejection from other survivors and those who are supposedto help.Violence exists in each corner of the world — in low,medium and high income countries, in urban slums,school classrooms, behind the locked doors of homesand institutions and through technology — and it canboil to a peak in disasters. Again and again in disastersthe risk of violence — people hurting other people,or people hurting themselves — intensifies as fragileprotective systems become strained or even collapse,stress levels soar, and people engage in harmful orexploitive behaviour. Populations that already face thehighest risks, such as children and women, becomeeven more threatened. A woman is attacked at dusk asshe seeks shelter in a crowded camp. A girl is forcedto trade her body to feed her family. A boy is beaten,as others watch in silence, and then abandoned in afrightening and lonely environment. A gang steals fromand threatens people in a shelter. A father loses hislivelihood and unleashes his sense of shame and angeron his family. An elderly man’s despair leads him to takehis own life. Stories like these are common in disasters;this is not acceptable.Yet, for all the challenges, the International Federationof <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> and <strong>Red</strong> Crescent Societies (IFRC) isnot without solutions. Violence, while complex andfrustrating, is not inevitable. In fact, like the risk of otherpublic health crises such as cholera, respiratory illnesses,measles, malaria and lack of nourishment thatcan escalate in disasters, violence can be contained,curbed and ultimately prevented. The ability of violenceto thrive on ignorance, secrecy, denial and the chaos ofdisasters can be thwarted.This report provides best practices to address violenceduring and after disasters and challenges us, as disasterresponders, to respond to this problem in all of ourwork through early and proactive action, using a publichealth approach.The International Federation has an essential role andmany assets to tip the scales in favour of safety: ourFundamental Principles, dedicated local volunteers,networks of diverse partnerships including auxiliariesto government, a recognized role as leading disasterresponders, and a history of facing down troublesomeplagues to humanity. Now we must acknowledge thepredictable and preventable problem of violence indisasters, accelerate our action, and influence others toalso respond. Now is the time to translate this commitmentfrom an aspiration into a reality.Bekele GeletaSecretary GeneralInternational Federationof <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> and<strong>Red</strong> Crescent SocietiesConrad SauvéSecretary General<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>Societychristopher black, IFRC

10 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 11WHY VIOLENCEESCALATES IN DISASTERSSocial determinantsThere is no single factor that puts people at risk ofinterpersonal or self-directed violence during and afterdisasters. Rather, people hurt other people and hurtthemselves due to a harmful mixture of complex riskfactors, or social determinants, between individuals andwithin their families, communities and societies. Theseexist before a disaster happens and intensify duringdisasters. The combination of the social determinantsvaries in each unique place and their intensity shifts asthe situation on the ground changes.While there are many variables that increase the risk ofviolence during a disaster, common underlying socialdeterminants include→→gender- and age-based inequalities and discrimination,→→social isolation and exclusion,→→harmful use of alcohol and other substances,→→income inequality,→→lack of protection systems, and→→misuse of power.Prevention efforts that address these common factorsthus have the potential to decrease the occurrence ofmultiple forms of violence. While these factors increasethe risk of violence during or following a disaster, itshould be emphatically clear that disasters themselvesdo not cause violence.In essence, during disasters a combination of negativeshocks reinforces one another. Social and communitysupport systems become strained, stress upon familiesand individuals begins to reach a boiling point, peopleresort to unhealthy coping mechanisms such as substanceabuse, those who are marginalized are pushedfurther to the margins and become more desperate anddependent, and protective mechanisms are either nonexistent,overstretched or under enforced. This results inthe increased likelihood of people losing self-control ormisusing power to take advantage of others.Figure:Social Determinants in Disasters that Increase the Risksfor Self-Directed and Interpersonal Violence xxi• History of violence• Disabilities from thedisaster• Relationship, materialand livelihood lossesfrom the disaster• Psychological trauma• Increased stress• Pyschological/personal-ity disorder• Alcohol/substance abuse• Separation from family• Socially excluded/marginalized• Access to lethal means/weapons• Victim of childmaltreatment• Lack of preventioneducation• History of violence• Injuries from the disaster• Loss of family members• Harmful parentingpractices• Increased stress onfamily members• Tensions from changesin family roles andresponsibilities• Alcohol/substancemisuse• Lack of informal supportsystems from family andfriends• Lack of preventioneducation• Poverty• Limited access to basicneeds• High unemployment• High crime levels• Inadequate victim careservices• Insecure and crowdeddisplacement settings• Weak protection systems• Lack of preventioneducation• Poverty• Economic disparities• Weak economic safetynets• Gender inequality• Age inequality• Lack of protection laws• Poor rule of law• Cultural norms that supportviolence• Access to lethal means/weaponsINDIVIDUALintimaterelationshipscommunitysociety/culturejosé manuel JIMeNez, IFRC

12 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 13PROFILE: HONDURAS“Without appropriate management,disaster shelters areat risk of becoming insecurespaces, exposing families tovarious risks. This aggravatesthe trauma of families whoare already coping with thephysical and psychologicaleffects of the disaster.”Maria Elisa Alvarado, Director General,Honduran <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>Since 1998, the Honduran <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>has been involved in numerousresponses to hurricanes, droughtand a 2009 earthquake. Much of itslearning about violence followingdisasters comes from the experienceof managing shelters followingHurricane Mitch, a devastating hurricanethat swept through CentralAmerica in 1998, with estimates ofover ten thousand people killed andover two million made homeless.“At the request of the government,the <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> took over themanagement of shelters housing1,372 families (6,676 people),” recallsMaria Elisa Alvarado, Director Generalof the Honduran <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>. An averageof 600 families (3,600 people)remained in the Tegucigalpa sheltersfor three and a half years. “Given thetransitory nature of how people lived,and the difficult urban environment,we saw a number of social problemssuch as family violence and gangviolence which caused insecurity, andwere exacerbated by the crowdedconditions.”Sheltered families came from differentlow-income neighbourhoodsand living quarters, each sufferingthe loss of family members andbelongings, and facing great challengesto recovery. In the shelters,the situation worsened because ofcrowding and a lack of communitystructures. Gangs took advantageof the situation, with tragic consequences:there were 18 murdersinside the shelters. “Violence wasthe product of a lack of economicopportunities, educational andorganizational resources, and poorsecurity,” says Alvarado.The Honduran <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> workedwith the Spanish <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> andother organizations to address theissues in the shelters. “We madedealing with this situation a priority,and took a much more active role incommunity organizing because werecognized that success in any otherarea was dependent on success inthis,” said Alvarado. They began byidentifying positive leaders in thecommunity and encouraged themto play a role in community projectcommittees. Dialogue and groupcohesion across the leadership ofthe committees was promoted. The<strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> also reached out to familiesof gang members and consultedwith experts on Honduran youthgangs to get advice.Consultation with residents wasdone, in part, by mapping theneeds and perspectives of differentgroups: men, women, youth, children,and the elderly. This approachof segregating the groups led to amore comprehensive picture of thechallenges people faced, includinggender discrimination, lack of jobs,high cost of basic staples, excessiveconsumption of alcohol, domesticviolence, teen pregnancy and pooreducation.This focus on facilitating communicationand participation paid off,helping shelter residents to breakdown the isolation and begin toaddress, as a community, the problemsthey faced. According to oneformer resident who played a role inthe shelter committees, the key wasto find the right way to help the shelterresidents help themselves: “wewere not looking to have the food putinto our mouths; we needed collaborationas much as possible to supportus in improving the conditionsof our lives.” With greater autonomyand participation, communitiesbecame more resilient, better ableto tolerate their losses and to tolerateeach other in their close livingsituations. “We promoted the idea ofself-management, involving peoplein the planning, management andfacilitation of programming,” notesAlvarado.The Honduran <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>offers the following lessonslearned:→→Avoid, as much as possible, massiveconcentrations of people inone place.→→Involve communities in the managementof shelters and theirprograms; there is an importantrole for the <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> in facilitatingand organizing participation,and ensuring that tasks andresponsibilities are clear.→→Provide more support andresponse to the conditions ofpeople who are sheltered in hostcommunities.→→Work directly with communitiesand families to allow opportunitiesfor dialogue around violence, itsrisk factors and solutions.→→Seek to ensure that the stay inshelters is as short as possibleand pursue alternatives with theauthorities to normalize the lives offamilies as quickly as possible.→→Invest in building the skills ofresponse teams, including recognizingthe triggers that can lead toviolence.→→Recognize the need for capacitybuilding, awareness andcounselling support to staff andvolunteers.Family whose home was destroyed by hurricane Mitch living at a stadium, San Pedro Sula, Honduras. \\ © Sean Sprague \\ spraguephoto.com

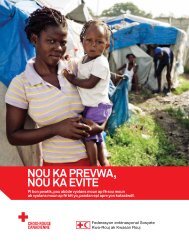

16 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 17PROFILE: HAITItalia frenkel, american red cross“Following the earthquake, wesaw a great solidarity betweenpeople, especially amongstour volunteers. However wehave also seen that the livingconditions people face sincethe earthquake have led to anincrease in violence. We areworking with our partners,staff and volunteers to integrateviolence preventionacross all our programs, andintegrate it into the trainingof our volunteers.”Dr. Michaële Amédée Gédéon, President,Haitian <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> SocietyThe Haitian <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> Society(HRCS), in partnership with theSpanish <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>, has worked toreduce levels of violence in communitieslike Bel Air for a numberof years. However, followingthe devastating earthquake ofJanuary 12, 2010, this work tookon a new priority. “Violence hasincreased, it is physical, emotional,and sexual…there are many victims,especially the young,” said an HRCScommunity mobilization officer.“There are many problems in thecamps, overcrowding, insufficientlatrines, and many rapes. We seechildren left to themselves, withgirls at particular risk,” added FernaVictor, Branch Development Directorfor the HRCS.While violence is not new to Haiti,the earthquake increased thevulnerability and risk. “Disaster andviolence go together because onecan cause the other,” notes an HRCSvolunteer. “There are a number offactors that can help promote —or prevent — violence, even indifficult conditions such as ours,”said Dr. Gédéon. “A camp wherethere is light at night is safer thanone where there is not. Some campsare safe spaces, others are not.”Violence prevention work in Haitihas included practical actions, suchas working with the InternationalFederation to improve lighting in thecamps of La Piste and Annexe de laMairie, and the neighbourhood ofDelmas 30. An SMS/phone text andradio campaign was also launchedprovidinginformation on violence preventionand how victims of violence can gethelp. HRCS leadership also participatedin a <strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>hosted three-day “Ten Steps toCreating Safe Environments” trainingto advance non-violence withinthe HRCS and its programs, anddeveloped an action plan.“Violence is hidden, it is not easy totalk about,” said one staff member.“This work has given me heart. Thereis too much violence in my country…With the <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>, I can see that thepossibility to reduce violence exists.”Integrated into the HRCS action plan areconcrete steps to protect volunteers fromviolence such as working in pairs andlearning how to keep themselves safe.Listening to victims of violence and givingthem the help they need are critical aspectsof volunteer training.Next steps for the HRCS include expandingviolence prevention work across the countryand continuing training for staff andvolunteers in how to protect themselves andothers. Engaging communities in violenceprevention work is also a priority. As oneHRCS volunteer explains, “adults train theyouth, youth train the children, and childrenare our future.”

20 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 21USING A PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACHTO PRIORITIZE PREVENTIONDisasters driven by theforces of nature are oftenunpredictable and cannotbe prevented, yet theirimpact can be reduced.Thus “disaster risk reduction”language is a suitableparadigm. In contrast,violence is not unpredictableor shaped by inevitableforces of nature, evenin disasters. Violence is aproduct of human mindsets,behaviours and the choicesindividuals make of theirfree will.In the same way that other publichealth crises such as diarrheal disease,respiratory illness, malnutritionand the spread of infectiousdisease can be anticipated andaddressed, so can interpersonaland self-directed violence.Part of the solution lies in theapproach to countering the risk.Countering the risk of violencerequires a move away from reactiveresponses after violence happens toa proactive “upstream” approach tostop violence from happening in thefirst place. xxxiA public health approach to violenceprevention focuses on a sciencebasedmethodology in which→→population-based data is gatheredto describe the problem, its scope,causes and consequences;→→risk and protective factors aredefined; and→→research-based interventionsare piloted, measured and thenscaled up.Even small investments in preventioncan lead to large and longlastingimpacts. This is true not onlyin development settings but alsoin situations of emergencies andrecovery.A public health approach thatrelies on comprehensive preventionstrategies, integrates justice,gender, and human rights perspectives,and aims to reach theentire population through primaryprevention, rather than only somesegments, is required. The designand implementation of preventionprograms and protection systemsneed to acknowledge and leverageindividual and communityresilience so that programs andsystems are “strength-based” andfocus not only on people’s vulnerabilitiesbut also their capacities.MOVING FROMPAPER TO PRACTICE:IMPLEMENTINGEXISTING STANDARDSPreventing violence in disastersis not a new dialogue. Work from anumber of agencies and coalitionsin recent years have promoted theintegration of safety, protectionand violence prevention into thecore practice of humanitarian workin disasters. However, the challengeof moving these standardsfrom paper to practice remains.Below are examples of standards,guidelines and a charter that theInternational Federation has formallysupported.The Sphere ProjectHumanitarian Charter andMinimum Standards inHumanitarian ResponseAccording to the Sphere Standards,the rights to protection and securityare cross-cutting and includeprinciples such as avoiding exposingpeople to further harm in disastersdue to humanitarian action,ensuring people’s access to impartialassistance, protecting peoplefrom physical and psychologicalharm due to violence and coercion,and assisting with accessto remedies and recovery fromabuse. xxxiiInter-Agency StandingCommittee→→Guidelines for Gender-BasedViolence Interventions inHumanitarian Settings: Theessential message of the guidelinesis: “All humanitarian actorsmust take action, from theearliest stages of an emergency,to prevent sexual violence andprovide appropriate assistance tosurvivors/victims.” xxxiii→→Guidelines on Mental Healthand Psychosocial Support inEmergency Settings: Theseguidelines help humanitarianactors identify, monitor, preventand respond to protection threatsand failures through socialprotection and to abuses throughlegal protection. xxxivChildren’s Charter forDisaster Risk <strong>Red</strong>uctionThe development of this charterhas been led by several humanitarianagencies including PLAN,Save the Children, World Visionand UNICEF. Among its core elementsis that child protectionmust be a priority before, duringand after a disaster. xxxvamanda george, british red cross

22 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 23PROFILE: CANADA“We are reviewing our recoveryframework — trying tomove from the reactive tothe proactive, not just providingemergency services butalso violence preventionand psychosocial support —and looking at best practiceswithin the Movement forrelief and recovery.”Louise Geoffrion, Deputy Director,Disaster Management, <strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>In the past several years, the provincesof Saskatchewan, Manitobaand Alberta have experiencedcomplex, large scale disastersincluding simultaneous forest firesand massive flooding. According toforecasts, this is a trend that willcontinue for several more years. Theresult has been extended evacuations,lengthy recovery periods andcomplicated assistance programsfor both households and communities.The continuous re-occurrenceof flooding prevents full recovery formost families and decreases theirsense of security and safety whileincreasing financial concerns anduncertainty.According to <strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>Provincial Director, Cindy Fuchs,local <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> responders havewitnessed this tension and frustrationturn into violent reactions ina variety of ways: “in some casesit is an increase in interpersonalviolence where evacuation sheltersare located. In some cases the angerand frustration is directed at localauthorities or <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> workersthemselves.”The impact of violence can be difficultto measure. In Slave Lake,Alberta, clients told local recoveryteams that there had beenan increase in interpersonalviolence following the fires whichdestroyed much of the town andcaused $700 million in damages,even though official statistics ondomestic violence had gone down.“Community members said theybelieved that less people werereporting violence, and that thedisplacement of families to othercommunities meant that the problemof increased violence movedwith them,” said Fuchs.However, <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> case workershave also heard from individualswho say that the disruption causedby a disaster provided them withan opportunity to leave an alreadyabusive situation.“Exposure to issues of interpersonalviolence, violence directed at hostcommunities, or even at the <strong>Red</strong><strong>Cross</strong> itself can lead to increasedstress,” says Ange Sawh, Director ofDisaster Management for WesternCanada. In some cases this has ledto personal issues at home if peopleare unable to cope with the level ofstress they are experiencing.emergency evacuation of community members from Wollaston Lake Hatchet Lake First Nationdue to forest fires in Northern Saskatchewan \\ Richard Marjan, The Star Phoenix.<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> hasidentified a number of lessonslearned and best practicesfrom recent responseexperiences:→→Increase specific programming fordealing with the emotional impactsthat occur in a disaster event —both for <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> responders aswell as people in the affected community.The response to the psychologicalwell-being of individualsand families needs to be proactive.Waiting for a problem to arise,means the response is too late.→→Prepare staff and volunteers toanticipate and address issues ofinterpersonal and community violence,and to protect people moreeffectively when violent situationsarise. Some steps that have beenidentified include adapting disasterresponse training materials toinclude more content on violenceprevention, and developing casestudies based on actual eventsto help workers expand theirunderstanding of how to handlesituations in which violence occursor is reported to have occurred.→→Collect data and have a sense ofwhat is going on in the communityto anticipate challenges andrespond to them.→→Consider the capacity of localorganizations and authorities toaddress and respond to violence.<strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> programs need to linkwith these local programs.→→Include violence preventionprogramming as part of disasterresponses; the linkage has shownpositive results especially foraddressing interpersonal violence.Where prevention programming hasbeen introduced, people are talkingto the <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> about violence.→→Work with communities on violenceprevention prior to a disasterbecause that approach ismore effective than introducingviolence prevention during or aftera disaster.→→Draw on best practices fromthe ICRC security resourceSafer Access and the experienceof international colleagues.

26 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 272EMERGENCY RESPONSE ANDEARLY RECOVERYPrioritize the prevention of violenceIn the same way that the risk forother public health emergencies areclosely monitored and respondedto in disasters, addressing violencealso requires attention and resourcingand should include preventioneducation campaigns, masscommunication and on the groundmitigation efforts.Respond rapidlyRight from the initial assessmentsdone by FACT or Pan-AmericanDisaster Response Unit (PADRU)teams, violence prevention andaddressing the impacts of violencemust be made a cross-cutting issuethat is part of decision making andplanning priorities. The followingquestions can help to determine keyfactors that should be mapped inthe immediate response:• What functioning, trusted andaccessible support systems andprotective factors are available?• What are the specific risks forviolence within the context of theaffected communities?• What police, UN, private, communityor other security measures arein place?• Who is vulnerable to violence, whyand where?Collect data and monitorData and statistics on interpersonaland self-directed violence need tobe collected at key points of contactwith beneficiaries. Data collectioncan occur as a part of patient visitsto temporary or permanent healthcarefacilities as an integral part ofroutine morbidity surveillance (seeSphere 2011 Handbook for samplereporting forms). Statistics can alsobe collected at food distributionpoints, shelters, etc.Support community-based socialsupport and self-helpFamily and community mechanismsfor protection and psychosocialsupport should be promoted. Keyactivities can include keepingfamilies together, whenever possible;supporting adults to preventchildren from becoming separatedfrom their families; organizing familytracing and reunification for childrenand adults separated from theirfamilies; and preserving family unityand enabling people from particularvillages/communities or supportnetworks to live in the same area ifthey are displaced.Speak up; raise our collective voiceThe threat of violence and theavailability of prevention strategiesand helping resources need to becommunicated rapidly, widely andrepeatedly through technology,social media, mass communication,high level and local networks, andword of mouth.Advocate to government andhumanitarian agency partnersAction at the ground level can yieldbenefits, but it is far more effectiveif it is complemented with humanitariandiplomacy to high-levelauthorities. Decisions at these levelscan impact systems, resources,attention and action on the ground.Key humanitarian diplomacy messagesand tools need to focus onpersuading relevant governmentand humanitarian agencies to putin place environmental systemssuch as lighting, adequate toiletfacilities, prevention/mitigation/response education, protection andsecurity systems.3LONG-TERM RECOVERY ANDDEVELOPMENTTake a long-term view and apply acomprehensive approachResponding to violence in disastersis essential. However, on its own itis not enough — action in crises canonly yield finite results. For violenceto be addressed in a comprehensivemanner, primary prevention actionsare required in disaster preparedness,during a disaster and into therecovery and development phases.Similar to other deeply embeddedproblems like HIV, Mother, Newbornand Child Health, and Tuberculosis,violence cannot be uprooted in sixmonthor two-year project cycles.Rather, a long-term approach withadequate resources, technical supportand attention is essential.Focus on priority actions for violencepreventionBased on the needs of local communities,the capacity of the <strong>Red</strong><strong>Cross</strong> <strong>Red</strong> Crescent National Societyand the roles of other partnersaddressing violence, there are anumber of priority actions that canbe pursued by National Societiesto support long-term safety. Theseinclude initiatives for addressingalcohol and substance misuse andabuse, managing stress, counteringprejudice against stigmatizingconditions, and promoting personalsafety and non-violence inhomes, schools, workplaces and incommunities.ifrc

28 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 29benoit matsha-carpentier, IFRC4CROSS CUTTING ACTIONSACROSS THE DISASTERRESPONSE CYCLEEnsure opportunities for beneficiaryparticipation and accountabilityThe people who benefit from interventions,such as children, youthand women, need to have the opportunityfor participation, ownershipand leadership at all levels includingassessment, design, implementation,monitoring and evaluation.Beneficiaries’ strengths as well astheir vulnerabilities need to be consideredin defining prevention andprotection actions. It is also importantto ensure that beneficiaries havea clear, accessible and safe feedback/complaintsmechanism.Leaders must leadThe role of senior leadership incommunities, governments andhumanitarian agencies is pivotal.When leaders prioritize safety, muchcan be achieved; when leadersfail to fulfil their responsibility toaddress violence, the consequencesfor organizations and beneficiariescan be deep and long-lasting. Notonly do leaders set the tone forhow a disaster will be respondedto and what the priorities are, theyalso determine how and if peopleabusing their power will be heldaccountable.Incorporate genderThe particular needs and strengthsof women, men, girls and boys andother gender identities need to beacknowledged, understood andincluded. Understanding the genderroles and responsibilities of malesand females in affected communitiesand how they have been influencedby the disaster, the status of femalesin the society including legal status,and the level of access and controlof resources such as relief items andmoney is important.Include children and youthChildren and youth need to participateand be represented, asappropriate, in decision makingthat affects them. Preventingviolence against children and youthrequires a particular focus acrossthe disaster response cycle becausethey are the most at risk and theconsequences can be most seriousfor them. Young people are not onlyaffected by disasters; they alsohave a valuable role in rebuildingcommunities.Integrate into existing tools andapproachesThe financial, human and technicalresources and capacity to addressinterpersonal and self-directedviolence can vary widely amongorganizations, countries and evenwithin cities and communities. Assuch, a strengths-based approachthat integrates violence preventioninto existing programs, policies,procedures and training is essentialto maximize limited resources andto leverage what is already in placeand proven effective.Monitor, evaluate and define lessonslearnedEnsuring quality and effectiveness inprogramming is critical to successfulviolence prevention. Good intentionsare not enough. Clear measurementsof what works, what does not, andhow programming can be modified toimprove impact are necessary.BudgetAction requires money. Each levelof response — disaster risk reduction,emergency and early recovery,and long-term recovery anddevelopment — needs a budgetfor integrating violence prevention.Opportune and effective ways tosecure funds include adding violenceprevention into emergencyappeals and as a budget line intoDisaster Risk <strong>Red</strong>uction (DRR)and other sectors (e.g. BeneficiaryAccountability, Community BasedHealth and First Aid, HumanitarianValues, Organizational Development,and Youth).

30 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 31Profile:International FederationAmericas Zone“Violence prevention programmingamong NationalSocieties in the Americas hasa long history. Supportingpartnerships betweenNational Societies to findinnovative ways to addressissues of violence is the nextstep. The focus on promotingcultures of non-violence inStrategy 2020 and within theAmericas zone planning meansincreased attention and supportto National Societiesdoing this work, and morefocus on how to integrate violenceprevention into disasterpreparedness, response andrecovery activities and acrosscommunity programs in theregion. ”Jan Gelfand, Head of Operations,International Federation of <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> and<strong>Red</strong> Crescent Societies, Americas Zone“In the Americas, we have to addressviolence,” says Jan Gelfand, Head ofOperations for the Americas Zone.Violence has been identified by thePan American Health Organizationas the social pandemic of the 21 stcentury, with one study finding thatduring the period of 2004–2009 xxxvifour of the five most violent countriesin the world were within theAmerica’s region. Social inequality,social exclusion and a misuse ofpower are major factors escalatingthe risk of violence. “This canbe expressed in the form of suicide,assault, abuse exploitation, homicidesand gang activities,” explainsGelfand. “When people feel they can’trely on institutions to support andprotect them, violence may seem likethe only available way to negotiatethe challenges they face. We have toengage more across our programs,with a special emphasis on ourdisaster-related activities, to addressthe risk factors, and prevent violence.”Consistent with Strategy 2020, theAmericas zone office has increasedthe profile of violence preventionin the 2012–2015 zone- andcountry-specific Long Term PlanningFrameworks. “The focus is bothon strengthening National Societyand the International Federation’swork with communities to preventviolence, and also ensuring a safeenvironment for <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> staffand volunteers,” says Gelfand. Thisincludes violence prevention insituations of disaster and crisis, andalso integrating violence preventionactivities across institutional andprogram areas.Four thematic focus areas forintegrated zone programming havebeen identified: urban risk, migration,climate change and violence.In the Americas, the InternationalFederation will pursue a strategyof building on the points of connectionacross these areas throughintegrated community programming.The strategy also places increasedattention on the growing vulnerabilitiesand needs of particularlyhigh-risk communities. “We see thatthere are people living along thefault lines of inequality, poverty andinsecurity, with some communitiesparticularly affected by the changingpatterns of disaster risk and crises,”explains Gelfand. In practical terms,this means that violence preventionbecomes a core component of thework being done with communitiesand beneficiaries in disaster andcrisis operations, in urban settings,with migrant communities as well asother ongoing program areas.An important part of the InternationalFederation’s approach toaddressing violence is a focus onpolicies and systems to preventviolence within our own institutionsthrough the adoption of resourcessuch as the Ten Steps to CreatingSafe Environments.The Ten Steps framework includesanalyzing the specific context ofthe problem of violence, recognizingpeople’s specific vulnerabilitiesand resilience, defining and understandingthe risks and protectioninstruments, and training. This workis particularly important in preparingfor, responding to and recoveringfrom disasters. The Ten Steps frameworksupports staff and volunteers,ensuring that <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> and <strong>Red</strong>Crescent programs are delivered in asafe environment — whether that bein the context of ongoing communityactivities or during the intensity of adisaster operation.“Strategy 2020, and the InternationalFederation’s Strategy on ViolencePrevention, Mitigation and Responseare a wake-up call for the <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong><strong>Red</strong> Crescent Movement to assesswhat needs to be done and take concreteaction in the area of violenceprevention,” says Gelfand. “We haveput violence prevention, both in ourwork with communities and withinour own institutions, as one of thepillars of our commitment to reducingrisk and vulnerability. This is thevision and the plan in the Americas.”bolivian red cross

32 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 33CONCLUSIONIn disaster after disaster,the risk of interpersonaland self-directed violenceincreases from a combinationof factors. Althoughanyone can be vulnerableto violence, people withpre-existing vulnerabilitiesto violence, such as children,women and otherswho are marginalized, areat particular risk. Althoughthe problem of violencein disasters is complex, itis not inevitable. Violencecan be prevented. The riskof violence needs to beaddressed through a publichealth approach that is partof all programming sectorsin a disaster. Best practicesexist and can be implementedacross the disastermanagement cycle.RESOURCESInternational FederationStrategy on Violence Prevention, Mitigation and Response (IFRC)Gender Strategy (IFRC)forthcoming“Ten Steps to Creating Safe Environments”www.redcross.ca/tenstepsViolence Prevention Modules for IFRC Community Based Health and First Aid (CBHFA)email: respected@redcross.caA Practical Guide to Gender-Sensitive Approaches to Disaster Management (IFRC)ICRC“Safer Access”http://www.icrc.org/eng/resources/documents/resolution/council-delegates-resolution-7-2011.htm or,http://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/red-cross-crescent-movement/council-delegates-2011/cod-2011-6-1-nsdraft-resolution-eng.pdfNational Societies<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>, Resources for preventing child maltreatment, and bullying and harassment, and promotinghealthy youth relationships. Specific resources include, “Be Safe!” Violence Prevention Resources for Community-Based Programs for Adults, Youth and Childrenwww.redcross.ca/respected<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>, Violence Prevention Modules for Emergency Response Unit trainingemail: healtheru@redcross.ca<strong>Canadian</strong> <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>, Handbook on Preventing Violence against Childrenwww.redcross.ca/respectedSpanish <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>, Estrategia Regional de Prevencion de Violencia CentroAmérica, México y Caribe. (ERPV)http://www.cruzroja.es/portal/page?_pageid=174,12290203&_dad=portal30&_schema=PORTAL30Colombian <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>, Paz, Acción y Convivencia” / “Peace, Action and Coexistence.” (PACO)http://www.cruzrojacolombiana.org/publicaciones/pdf/Cartilla%20Paco_1372010_103353.pdfHumanitarian AgenciesWorld Health Organization, Preventing violence and reducing its impact: How development agencies can helphttp://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596589_eng.pdfUN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UNICEF and World Health Organization, World report onviolence against childrenhttp://www.unviolencestudy.org/Sphere Project, Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian responsehttp://www.sphereproject.orgInter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), Guidelines for gender-based violence interventions in humanitarian settings:Focusing on prevention of and response to sexual violence in emergencieshttp://www.humanitarianinfo.org/iasc/downloadDoc.aspx?docID=4402Children in a Changing Climate, Children’s charter: An action plan for disaster risk reduction for children by children.http://plan-international.org/files/global/publications/emergencies/Childrens_Charter%20new.pdfA child wearing a sticker calling for an end to violence against women,La Piste camp, Port-au-Prince, Haiti \\ Juliet Kerr, IFRC Violence Prevention

34 PREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLEPREDICTABLE, PREVENTABLE 35REferencesi. Butchart, A., Brown, D., Wilson, A., & Mikton, C. (2008). Preventing violence andreducing its impact: How development agencies can help. World Health Organization.Retrieved from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596589_eng.pdf.ii. Butchart, A., Brown, D., Wilson, A., & Mikton, C. (2008). Preventing violence andreducing its impact: How development agencies can help. World Health Organization.Retrieved from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596589_eng.pdf.iii. World Health Organization. (2010). Ten facts on violence prevention. Retrieved from:http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/violence/en/index.html.iv. Pinheiro, P.S. (2006). World report on violence against children. New York:United Nations; Butchart, A., Brown, D., Wilson, A., & Mikton, C. (2008).Preventing violence and reducing its impact: How development agencies canhelp. World Health Organization. Retrieved from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596589_eng.pdf; United Nations, General Assembly.(2006). In-Depth Study on All Forms of Violence against Women: Report of theSecretary General, 2006. A/61/122/Add.1. Retrieved from: http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/419/74/PDF/N0641974.pdf?OpenElement; Butchart,A., Brown, D., Wilson, A., & Mikton, C. (2008). Preventing violence and reducing itsimpact: How development agencies can help. World Health Organization. Retrievedfrom: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596589_eng.pdf.v. World Health Organization. (2011). Disease and injury regional estimates: Causespecificmortality: regional estimates for 2008. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_regional/en/index.html.vi. Klynman, Y., Kouppari, N. & Mukhier, M. (Eds.). (2007). World disasters report 2007:Focus on discrimination. International Federation of <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> and <strong>Red</strong> CrescentSocieties (IFRC).vii. Enarson, E. (2008). Violence against women following natural disasters.Encyclopaedia of interpersonal violence. SAGE Publications. Retrieved from:http://www.sage-ereference.comezp1.lib.umn.edu/view/violence/n540.xml.viii. Amnesty International. (2011). Aftershocks: Women speak out against sexualviolence in Haiti’s camps. Retrieved from: http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AMR36/001/2011/en; Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice. (2011). Sexualviolence in Haiti’s IDP camps: Results of a household survey; Clermont, C. (2011).Évaluation de la situation de la violence faite aux femmes et aux filles dans leszones de Martissant et Cité Soleil ; Davis, L., Gell, A., Joseph, M., Richards E.J.,Patel, S. & Romero, K. (2010). Legal petition claim of precautionary measures und.Retrieved from: article 25 of the Commission’s rules of procedure. InternationalWomen’s Human Rights Clinic at the City University of New York School of Law,Madre, The institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti, Bureau des AvocatsInternationaux, Morrison & Foerster LLP, The Centre for Constitutional Rights, andWomen’s Link Worldwide; Human Rights Watch. (2011). Country summary. WorldReport 2011; Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti and University of VirginiaSchool of Law. (2010). Our bodies are still trembling: Haitian women’s fight againstrape. Retrieved from: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2AFAD9E18B0B66604925776E000646D1-Full_Report.pdf; International Gay and LesbianHuman Rights Commission / SEROVIE. (2011). The impact of the earthquake,and relief and recovery programs on Haitian LGBT people. Retrieved from:http://www.iglhrc.org/binary-data/ATTACHMENT/file/000/000/505-1.pdf.ix. Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice. (2011). Sexual Violence in Haiti’s IDPCamps: Results of a household survey. Retrieved from: http://www.chrgj.org/press/docs/Haiti%20Sexual%20Violence%20March%202011.pdf.x. UNHCR. (2011). Driven by desperation: Transactional sex as a survival strategyin Port-au-Prince IDP camps. Retrieved from: http://www.unhcrwashington.org/atf/cf/%7Bc07eda5e-ac71-4340-8570-194d98bdc139%7D/SGBV-HAITI-STUDY-MAY2011.PDF.xi. Avery, J.G. (2003). The aftermath of a disaster: Recovery following the volcaniceruptions in Montserrat, West Indies. West Indian Medical Journal, 52: 131–5.xii. Alba, W. & Luciano, D. (2008). Salud sexual y reproductive y violencia en personasvulnerables: La tormenta Noel en Republica Dominicana. Santo Domingo, DominicanRepublic: INSTRAW and UNFPA.xiii. World Health Organization (2005). Fact sheet: Violence & disasters. World HealthOrganization Department of Injuries and Violence Prevention. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/violence_disasters.pdf.xiv. CIET International. (1999). Social audit for emergency and reconstruction, phase 1 –April. Coordinadora Civil para la Emergencia y la Reconstruccion (CCER); Managua,Nicaragua.xv. Larrance, R., Anastario, M. & Lawry, L. (2007). Health status among internallydisplaced persons in Louisiana and Mississippi travel trailer parks. Annals ofEmergency Medicine, 49, 590–601.xvi. Harville, E.W., Taylor, C.A., Tesfai, H., Xiong, X. & Buekens P. (2011). Experience ofHurricane Katrina and reported intimate partner violence. Journal of InterpersonalViolence, 26(4), 833–845.xvii. Keenan, H.T., Marshall, S.W., Nocera, M.A. & Runyan, D.K. (2004). Increased incidenceof inflicted traumatic brain injury in children after a natural disaster. AmericanJournal of Preventive Medicine, 26 (3), pp. 189–93.xviii. Enarson, E. (1999). Emergency preparedness in British Columbia: Mitigatingviolence against women in disasters. An issues and action report for provincialemergency management authorities and women’s services, 13. Retrieved from:http://www.onlinewomeninpolitics.org/sourcebook_files/Resources/Report-%20Emergency%20Preparedness%20in%20British%20Columbia%20(Mitigating%20Violence%20Against%20Women%20in%20Disasters).pdf.xix. Pinheiro, P.S. (2006). World report on violence against children. New York: UnitedNations.xx. Enarson, E. (1999). Emergency preparedness in British Columbia: Mitigatingviolence against women in disasters. An issues and action report for provincialemergency management authorities and women’s services. Retrieved from:|http://www.onlinewomeninpolitics.org/sourcebook_files/Resources/Report-%20Emergency%20Preparedness%20in%20British%20Columbia%20(Mitigating%20Violence%20Against%20Women%20in%20Disasters).pdf.xxi. Adapted from the ecological model used in: Krug, E., Dahlbert, L., Mercy, J., Zwi, A.& Lozano, R. (Eds.) (2002). World report on violence and health. Geneva: World HealthOrganization.xxii. Birkeland, Nina M., Halff, Kate and Jennings, Edmund (Eds.) (2010). InternalDisplacement: Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2009. (pp.14).Switzerland: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre.xxiii. Enarson, E. (1999). Emergency preparedness in British Columbia: Mitigatingviolence against women in disasters. An issues and action report for provincialemergency management authorities and women’s services, 13. Retrieved from:http://www.onlinewomeninpolitics.org/sourcebook_files/Resources/Report-%20Emergency%20Preparedness%20in%20British%20Columbia%20(Mitigating%20Violence%20Against%20Women%20in%20Disasters).pdf.xxiv. Ferris, E. (2010). Natural disasters, conflict and human rights: Tracing theconnections. The Brookings Institution. Retrieved from: http://www.brookings.edu/speeches/2010/0303_natural_disasters_ferris.aspx.xxv. Ferris, E. (2010). Natural disasters, conflict and human rights: Tracing theconnections. The Brookings Institution. Retrieved from: http://www.brookings.edu/speeches/2010/0303_natural_disasters_ferris.aspx.xxvi. Enarson, E. (2008). Violence against women following natural disasters.Encyclopaedia of interpersonal violence. SAGE Publications. Retrieved from:http://www.sage-ereference.comezp1.lib.umn.edu/view/violence/n540.xml.xxvii. Holt, K. & Hughes, S. (2007). UN staff accused of raping children in Sudan. TelegraphMedia Group. Retrieved from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk; BBC News. (2007).UN probes ‘abuse’ in Ivory Coast. BBC News – United Kingdom. Retrieved from:http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/africa/6909664.stm; United Nations HighCommissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) & Save the Children United Kingdom. (2002).Note for implementing and operational partners by UNHCR and Save the Children-UK on sexual violence and exploitation: The experience of refugee children in Guinea,Liberia and Sierra Leone based on initial findings and recommendations fromassessment mission 22 October – 30 November 2001. Retrieved from: http://www.unhcr.ch/cgibin/texis/vtx/partners/opendoc.pdf?tbl=PARTNERS&id=3c7cf89a4;Save the Children United Kingdom. (2006). From camp to community: Liberiastudy on exploitation of children. Retrieved from: http://www.savethechildren.it/2003/download/pubblicazioni/Liberia/Liberia_sexual_exploitation_editedLB.pdf; Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): MONUC troops among the worstsex offenders. (2006, August 28). IRIN Humanitarian News and Analysis – Online.Retrieved from: http://www.irinnews.org/report.aspx?reportid=60476.xxviii. Butchart, A., Brown, D., Wilson, A., & Mikton, C. (2008). Preventing violence andreducing its impact: How development agencies can help. World Health Organization.Retrieved from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596589_eng.pdf.xxix. Butchart, A., Brown, D., Wilson, A., & Mikton, C. (2008). Preventing violence andreducing its impact: How development agencies can help. World Health Organization.Retrieved from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596589_eng.pdf.xxx. Ferris, E. (2010). Natural disasters, conflict and human rights: Tracing theconnections. The Brookings Institution. Retrieved from: http://www.brookings.edu/speeches/2010/0303_natural_disasters_ferris.aspx.xxxi. Delaney, S. (2006). Protecting children from sexual exploitation and sexual violencein disaster and emergency situations. Bangkok, Thailand: ECPAT International.xxxii. Sphere Project. (2011). The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and MinimumStandards in Humanitarian Response. Retrieved from: http://www.sphereproject.org/component/option,com_docman/task,cat_view/gid,70/Itemid,203/lang,english/.xxxiii. Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) (2005). Guidelines for gender-basedviolence interventions in humanitarian settings: Focusing on prevention of andresponse to sexual violence in emergencies (Field test version). Geneva: IASC.xxxiv. Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) (2008). Mental health and psychosocialsupport: Checklist for field use. Geneva: IASC.xxxv. Children in a Changing Climate. (2011). Children’s charter: An action plan for disasterrisk reduction for children by children. Retrieved from: http://plan-international.org/files/global/publications/emergencies/Childrens_Charter%20new.pdf.xxxvi. Geneva Declaration Secretariat. (2011). The Global Burden of Armed Violence 2011.Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development. Retrieved from:http://www.genevadeclaration.org/measurability/global-burden-of-armed-violence/global-burden-of-armed-violence-2011.html.The International<strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> and<strong>Red</strong> CrescentMovement operatesunder sevenFundamentalPrinciples.HumanityThe <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> endeavours to preventand alleviate human suffering whereverit may be found, protecting lifeand health and ensuring respect for thehuman being.ImpartialityThe <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> is guided solely by theneeds of human beings and makes nodiscrimination as to nationality, race,religious beliefs, class, or politicalopinions.NeutralityIn order to continue to enjoy the confidenceof all, the movement may not takesides in hostilities or engage at any timein controversies of a political, racial,religious, or ideological nature.IndependenceThe national societies must alwaysmaintain their autonomy so thatthey may be able at all times to act inaccordance with the principles of themovement.Voluntary ServiceIt is a voluntary relief movement notprompted in any manner by desire forgain.UnityThere can be only one <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> or one<strong>Red</strong> Crescent society in any one country.It must be open to all. It must carry onits humanitarian work throughout itsterritory.UniversalityThe International <strong>Red</strong> <strong>Cross</strong> and <strong>Red</strong>Crescent Movement, in which all societieshave equal status and share equalresponsibilities and duties in helpingeach other, is worldwide.

edcross.ca | ifrc.org