Haiti – Dominican Republic - Disasters and Conflicts - UNEP

Haiti – Dominican Republic - Disasters and Conflicts - UNEP Haiti – Dominican Republic - Disasters and Conflicts - UNEP

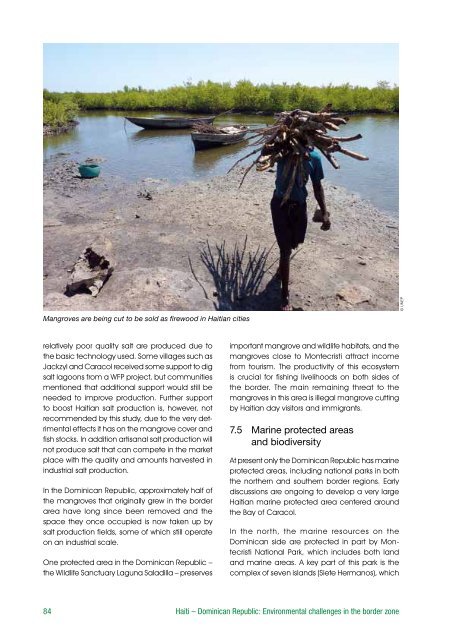

Mangroves are being cut to be sold as firewood in Haitian cities© UNEPrelatively poor quality salt are produced due tothe basic technology used. Some villages such asJackzyl and Caracol received some support to digsalt lagoons from a WFP project, but communitiesmentioned that additional support would still beneeded to improve production. Further supportto boost Haitian salt production is, however, notrecommended by this study, due to the very detrimentaleffects it has on the mangrove cover andfish stocks. In addition artisanal salt production willnot produce salt that can compete in the marketplace with the quality and amounts harvested inindustrial salt production.In the Dominican Republic, approximately half ofthe mangroves that originally grew in the borderarea have long since been removed and thespace they once occupied is now taken up bysalt production fields, some of which still operateon an industrial scale.One protected area in the Dominican Republic –the Wildlife Sanctuary Laguna Saladilla – preservesimportant mangrove and wildlife habitats, and themangroves close to Montecristi attract incomefrom tourism. The productivity of this ecosystemis crucial for fishing livelihoods on both sides ofthe border. The main remaining threat to themangroves in this area is illegal mangrove cuttingby Haitian day visitors and immigrants.7.5 Marine protected areasand biodiversityAt present only the Dominican Republic has marineprotected areas, including national parks in boththe northern and southern border regions. Earlydiscussions are ongoing to develop a very largeHaitian marine protected area centered aroundthe Bay of Caracol.In the north, the marine resources on theDominican side are protected in part by MontecristiNational Park, which includes both landand marine areas. A key part of this park is thecomplex of seven islands (Siete Hermanos), which84 Haiti – Dominican Republic: Environmental challenges in the border zone

is important for biodiversity conservation in theCaribbean and part of the Atlantic as they hostlarge scale breeding grounds for marine birds(mainly gannets and boobies from the Sulidaefamily). The protection of the surrounding marineareas, however, seems to be effective only duringthe six month bird breeding season during whichthe Dominican Republic National Park authoritiesactively patrol the islands.The border zone’s marine and coastal biodiversitycan be found in four main ecosystems: 1) theinsular shelf, where there are a great variety ofendemic species of corals and marine grasslands,and where the species that hold significanteconomic interest for fisheries are concentrated.2) Mangroves and coastal lagoons, which areconsidered to be among the most importantecosystem groups for the reproduction of speciesof economic interest. 3) Beaches, which areimportant not only for tourism but also becausespecies – such as turtles and marine birds – nestthere. Some of the beach zones in the northernpart of the border area include islets that are ofcritical regional importance for bird reproduction.4) Rocky coastal cliffs, which are also veryimportant for bird reproduction.7.6 Transboundary trade in marinespeciesA fisherman in the Haitian border city of Anseà-Pitreshowing his catch. Fishermen reap thebenefits of having a marine protected area close byon the Dominican side of the border that acts as abreeding ground.In the south, the Dominican Jaragua Land andMarine National Park, is situated close to the border.Anecdotal evidence from fishermen on bothsides of the border is that this protected area maybe having a major positive impact on fishing yields.Marine parks with no-take zones act as sanctuariesfor fish to breed and grow, guaranteeing a steadysupply of mature fish to regional fisheries.© UNEPTrade in marine species across the border isimportant and a clear opportunity for increasedcooperation in the border zone. Dominicanfishmongers are for example present in theHaitian market of Anse-à-Pitre, buying much ofthe large fish and high-value species (lobster,crab, lambis) to resell them on the Dominicanmarket. In October 2007, from 500 to 1000pounds of fish were exported from Anse-à-Pitredaily. Haitian fishermen buying ice and fuelin Pedernales also sell their products in theDominican Republic. Dominicans also cross theHaitian border to sell the fish they cannot sell inthe Dominican Republic because they are toosmall to be permitted to be sold in the DominicanRepublic. 279Formal transboundary cooperation on thistransboundary trade is relatively limited and this iscurrently causing problems. One particular issuenoted in both the north and south was the lackof formal/state sanctioned dispute mediationmechanisms.Against this generally negative background, thereare however, some cooperation exceptions andsuccess stories. The most significant of these is thetransboundary cooperation between Haitian andDominican fisheries associations on the southerncoast, as can be seen in case study 6.Haiti – Dominican Republic: Environmental challenges in the border zone85

- Page 36 and 37: Map 6. The northern coast and the M

- Page 39 and 40: Map 8. The area surrounding the lak

- Page 41 and 42: although it is estimated to be much

- Page 43 and 44: Figure 3. Seasonality of food insec

- Page 45 and 46: e sold for a profit on the other si

- Page 47 and 48: viCase study 2. Comité Intermunici

- Page 49 and 50: Part 2 Identification andAnalysis o

- Page 51 and 52: and local issues. These include, fo

- Page 53: Lacking productive topsoil this lan

- Page 56 and 57: 5 Forest resources andterrestrial p

- Page 58 and 59: Satellite image 3. In the Massacre

- Page 60 and 61: un the risk of being either impriso

- Page 62 and 63: eing transported from the Dominican

- Page 64 and 65: 5.5 Collection of fuel woodFuel woo

- Page 66 and 67: !^5.6 Protected area management and

- Page 68 and 69: locations is contrasted with a degr

- Page 70 and 71: Enough is known, however, to be cer

- Page 72 and 73: plantations that the habitat will n

- Page 74 and 75: Satellite image 6. Just before reac

- Page 76 and 77: interventions if well designed do w

- Page 78 and 79: contaminated rivers are disease vec

- Page 80 and 81: crust substantial enough to be the

- Page 82 and 83: 7 Coastal and marineresources7.1 In

- Page 84 and 85: tuna, sea bream, yellowtail, hake,

- Page 88 and 89: Case study 6. Cooperation between f

- Page 90 and 91: private sector better informed. Cus

- Page 92 and 93: carrying money, and missing their d

- Page 94 and 95: etween these two cordilleras), but

- Page 96: Mineral exploration is starting in

- Page 99 and 100: assessment team are all small scale

- Page 101 and 102: Extreme poverty is a key driving fo

- Page 103 and 104: it is present. The Haitian populati

- Page 105 and 106: Atlantic storms will double in the

- Page 107 and 108: A charcoal kiln burning inside the

- Page 109 and 110: Table 5. Summary of the key recomme

- Page 111 and 112: Ten recommendations are provided un

- Page 113 and 114: oth environmentally damaging and li

- Page 115 and 116: Improving cooperation and governanc

- Page 117 and 118: f. Create and formalize fishing agr

- Page 119 and 120: g. In the long term, aim for variou

- Page 121 and 122: Haiti - Dominican Republic: Environ

- Page 123 and 124: Annex I - Report terminologyArgumen

- Page 125 and 126: Annex II - List of Acronyms and Abb

- Page 127 and 128: Annex IV - Table connecting thereco

- Page 129 and 130: 23. United States Census Bureau. (2

- Page 131 and 132: 73. UN Development Programme - Haï

- Page 133 and 134: 117. Urban Design Lab, Columbia Uni

- Page 135 and 136: 161. Miniel, L. (2012, 20 April). I

Mangroves are being cut to be sold as firewood in <strong>Haiti</strong>an cities© <strong>UNEP</strong>relatively poor quality salt are produced due tothe basic technology used. Some villages such asJackzyl <strong>and</strong> Caracol received some support to digsalt lagoons from a WFP project, but communitiesmentioned that additional support would still beneeded to improve production. Further supportto boost <strong>Haiti</strong>an salt production is, however, notrecommended by this study, due to the very detrimentaleffects it has on the mangrove cover <strong>and</strong>fish stocks. In addition artisanal salt production willnot produce salt that can compete in the marketplace with the quality <strong>and</strong> amounts harvested inindustrial salt production.In the <strong>Dominican</strong> <strong>Republic</strong>, approximately half ofthe mangroves that originally grew in the borderarea have long since been removed <strong>and</strong> thespace they once occupied is now taken up bysalt production fields, some of which still operateon an industrial scale.One protected area in the <strong>Dominican</strong> <strong>Republic</strong> <strong>–</strong>the Wildlife Sanctuary Laguna Saladilla <strong>–</strong> preservesimportant mangrove <strong>and</strong> wildlife habitats, <strong>and</strong> themangroves close to Montecristi attract incomefrom tourism. The productivity of this ecosystemis crucial for fishing livelihoods on both sides ofthe border. The main remaining threat to themangroves in this area is illegal mangrove cuttingby <strong>Haiti</strong>an day visitors <strong>and</strong> immigrants.7.5 Marine protected areas<strong>and</strong> biodiversityAt present only the <strong>Dominican</strong> <strong>Republic</strong> has marineprotected areas, including national parks in boththe northern <strong>and</strong> southern border regions. Earlydiscussions are ongoing to develop a very large<strong>Haiti</strong>an marine protected area centered aroundthe Bay of Caracol.In the north, the marine resources on the<strong>Dominican</strong> side are protected in part by MontecristiNational Park, which includes both l<strong>and</strong><strong>and</strong> marine areas. A key part of this park is thecomplex of seven isl<strong>and</strong>s (Siete Hermanos), which84 <strong>Haiti</strong> <strong>–</strong> <strong>Dominican</strong> <strong>Republic</strong>: Environmental challenges in the border zone