English - Balay Mindanaw

English - Balay Mindanaw English - Balay Mindanaw

LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KALINAWThe research team with Datu Mandedlyne (former Brgy. Capt. Agulio Nanulanof Hagpa, Impasug-ong, Bukidnon) during the Community Feedbacking andValidation workshop at Sitio Kiudto in Hagpa last January 6, 2006. (Standing[L-R]: Carmen C. Monter, Kalayaan Anjuli D. Gatuslao, Leah H. Vidal, DatuMandedlyne, Xx Dagapioso- Baconga. Sitting [L-R]: Jonas A. Penaso, MelodyU. Salise, and Jimson P. Hapson.)Our task was to document the conflict resolutionpractices of the Higaunon groups in the localities ofSangalan and Hagpa. But we wanted to approach it ina way that is different from other lumad studies. We wantedto be able to capture the dynamism of the practices: how theyare actually performed and are being shaped in the process oftheir performance. Veering away from the usual notion thathuman practices are “standardized routine that one simplygoes through (Bruner 1986:5),” we wanted to capture howthe Higaunons actually shape and form their practices basedon their execution of such. So we turned to anthropology ofexperience. This was initially formulated by Victor Turner ashis “rebellion against the structural-functional orthodoxy withits static model of social system (Babcock as cited in Bruner12

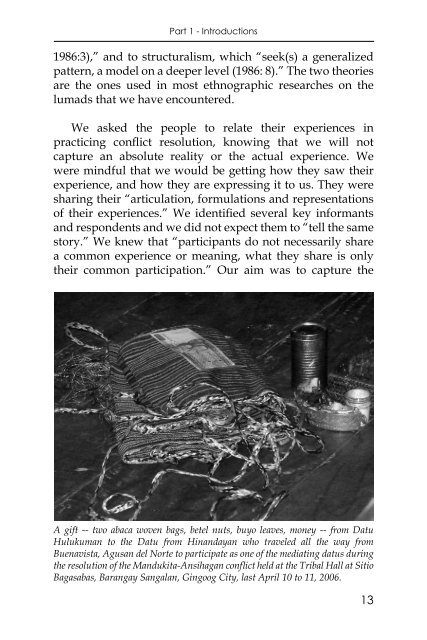

Part 1 - Introductions1986:3),” and to structuralism, which “seek(s) a generalizedpattern, a model on a deeper level (1986: 8).” The two theoriesare the ones used in most ethnographic researches on thelumads that we have encountered.We asked the people to relate their experiences inpracticing conflict resolution, knowing that we will notcapture an absolute reality or the actual experience. Wewere mindful that we would be getting how they saw theirexperience, and how they are expressing it to us. They weresharing their “articulation, formulations and representationsof their experiences.” We identified several key informantsand respondents and we did not expect them to “tell the samestory.” We knew that “participants do not necessarily sharea common experience or meaning, what they share is onlytheir common participation.” Our aim was to capture theA gift -- two abaca woven bags, betel nuts, buyo leaves, money -- from DatuHulukuman to the Datu from Hinandayan who traveled all the way fromBuenavista, Agusan del Norte to participate as one of the mediating datus duringthe resolution of the Mandukita-Ansihagan conflict held at the Tribal Hall at SitioBagasabas, Barangay Sangalan, Gingoog City, last April 10 to 11, 2006.13

- Page 3 and 4: LUMADNONGP AGKINABUHINGADTO SA KALI

- Page 5 and 6: This book is dedicated to all the L

- Page 7 and 8: Table of ContentsPrefaceiiiPART ONE

- Page 9 and 10: PrefaceWe commend Resource Center f

- Page 11 and 12: Part 1 - IntroductionsPart OneIntro

- Page 13 and 14: Part 1 - IntroductionsAn Orientatio

- Page 15: Part 1 - IntroductionsThese interes

- Page 18 and 19: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 20 and 21: 10LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA K

- Page 24 and 25: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 26 and 27: 16LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA K

- Page 28 and 29: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 30 and 31: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 32 and 33: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 34 and 35: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 36 and 37: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 38 and 39: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 40 and 41: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 42 and 43: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 44 and 45: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 46 and 47: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 48 and 49: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 50 and 51: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 52 and 53: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 54 and 55: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 56 and 57: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 58 and 59: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 60 and 61: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 62 and 63: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 64 and 65: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 66 and 67: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 68 and 69: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

- Page 70 and 71: LUMADNONG PAGKINABUHI NGADTO SA KAL

Part 1 - Introductions1986:3),” and to structuralism, which “seek(s) a generalizedpattern, a model on a deeper level (1986: 8).” The two theoriesare the ones used in most ethnographic researches on thelumads that we have encountered.We asked the people to relate their experiences inpracticing conflict resolution, knowing that we will notcapture an absolute reality or the actual experience. Wewere mindful that we would be getting how they saw theirexperience, and how they are expressing it to us. They weresharing their “articulation, formulations and representationsof their experiences.” We identified several key informantsand respondents and we did not expect them to “tell the samestory.” We knew that “participants do not necessarily sharea common experience or meaning, what they share is onlytheir common participation.” Our aim was to capture theA gift -- two abaca woven bags, betel nuts, buyo leaves, money -- from DatuHulukuman to the Datu from Hinandayan who traveled all the way fromBuenavista, Agusan del Norte to participate as one of the mediating datus duringthe resolution of the Mandukita-Ansihagan conflict held at the Tribal Hall at SitioBagasabas, Barangay Sangalan, Gingoog City, last April 10 to 11, 2006.13