Layout 8 - Winston Churchill

Layout 8 - Winston Churchill

Layout 8 - Winston Churchill

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

THE JOURNAL OF WINSTON CHURCHILLSPRING 2009 • NUMBER 142

THE CHURCHILL CENTRE & CHURCHILL MUSEUMaT THE CabINET WaR RooMS, LoNdoNUNITEd STaTES • UNITEd KINGdoM • CaNada • aUSTRaLIa® ®PaTRoN: THE LadY SoaMES LG dbE • WWW.WINSToNCHURCHILL.oRGFounded in 1968 to educate new generations on theleadership, statesmanship, vision and courage of <strong>Winston</strong> Spencer <strong>Churchill</strong>THE CHURCHILL CENTRE IS THE SUCCESSOR TO THE WINSTON S. CHURCHILL STUDY UNIT (1968) AND THE INTERNATIONAL CHURCHILL SOCIETY (1971),BUSINESS OFFICES200 West Madison StreetSuite 1700, Chicago IL 60606Tel. (888) WSC-1874 • Fax (312) 658-6088info@winstonchurchill.org<strong>Churchill</strong> Museum & Cabinet War RoomsKing Charles Street, London SW1A 2AQTel. (0207) 766-0122CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARDLaurence S. Gellerlgeller@winstonchurchill.orgEXECUTIVE VICE-PRESIDENTPhilip H. Reed OBEpreed@iwm.org.ukCHIEF OPERATING OFFICERDaniel N. Myersdmyers@winstonchurchill.orgDIRECTOR OF ADMINISTRATIONMary Paxsonmpaxson@winstonchurchill.orgEDUCATION PROGRAMS COORDINATORSuzanne Sigmansuzanne@churchillclassroom.orgDIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENTCynthia Faulknercfaulkner@winstonchurchill.orgBOARD OF TRUSTEES*EXECUTIVE COMMITTEEThe Hon. Spencer Abraham • Randy BarberDavid Boler* • Paul Brubaker • Randolph S. <strong>Churchill</strong><strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong> • David Coffer • Manus CooneyPaul Courtenay • Sen. Richard J. DurbinMarcus Frost* • Laurence S. Geller*Sir Martin Gilbert CBE • Richard C. Godfrey*Philip Gordon* • Hon Jack Kemp • Gretchen KimballRichard M. Langworth CBE* • Diane LeesThe Rt Hon Sir John Major KG CHChristopher Matthews • Sir Deryck Maughan*Michael W. Michelson • Joseph J. Plumeri*Lee Pollock • Philip H. Reed OBE* • Mitchell ReissKenneth W. Rendell* • Amb. Paul H. Robinson, Jr.Elihu Rose* • Stephen RubinThe Hon. Celia Sandys • The Hon. Edwina SandysHONORARY MEMBERS<strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong> • Sir Martin Gilbert CBERobert Hardy CBE • The Lord Heseltine CH PCThe Duke of Marlborough JP DLSir Anthony Montague Browne KCMG CBE DFCGen. Colin L. Powell KCB • Amb. Paul H. Robinson, Jr.The Lady Thatcher LG OM PC FRSFRATERNAL ORGANIZATIONS<strong>Churchill</strong> Archives Centre, CambridgeThe <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> Memorial Trust, UK, AustraliaHarrow School, Harrow-on-the-Hill, Middlesex<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> Memorial & Library, Fulton, Mo.INTERNET RESOURCESDanMyers, Webmaster, dmyers@winstonchurchill.orgJonah Triebwasser, Chatlist ModeratorWeb committee: Ian W.D. Langworth, Dan Myers, JohnDavid Olsen, Todd Ronnei, Suzanne SigmanACADEMIC ADVISERSProf. James W. Muller, ChairmanUniversity of Alaska, Anchorageafjwm@uaa.alaska.eduProf. John A. Ramsden, Vice ChairmanQueen Mary College, University of Londonjohn@ramsden.netProf. Paul K. Alkon, University of So. CaliforniaSir Martin Gilbert CBE, Merton College, OxfordCol. David Jablonsky, U.S. Army War CollegeProf. Warren F. Kimball, Rutgers UniversityProf. John Maurer, U.S. Naval War CollegeProf. David Reynolds FBA, Christ’s College, CambridgeDr. Jeffrey Wallin, PresidentAmerican Academy of Liberal EducationLEADERSHIP & SUPPORTNUMBER TEN CLUBContributors of $10,000 or more per year.Kenneth Fisher • Laurence S. GellerMichael D. Rose • Michael J. ScullyCHURCHILL CENTRE ASSOCIATESContributors to The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre Endowment,which offers three levels: $10,000, $25,000 and $50,000+,inclusive of bequests. Endowment earnings support thework of The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre & Museum at the CabinetWar Rooms, London.<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> AssociatesThe Annenberg Foundation • David & Diane BolerFred Farrow • Barbara & Richard LangworthMr. & Mrs. Parker H. Lee IIIMichael & Carol McMenamin • David & Carole NossRay & Patricia Orban • Wendy Russell RevesElizabeth <strong>Churchill</strong> Snell • Mr. & Mrs. Matthew WillsAlex M. Worth Jr.Clementine <strong>Churchill</strong> AssociatesRonald D. Abramson • <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>Samuel D. Dodson • Marcus & Molly FrostJeanette & Angelo Gabriel • Craig & Lorraine HornJames F. Lane • John & Susan MatherLinda & Charles PlattAmbassador & Mrs. Paul H. Robinson Jr.James R. & Lucille I. ThomasMary Soames AssociatesDr. & Mrs. John V. Banta • Solveig & Randy BarberGary J. Bonine • Susan & Daniel BorinskyNancy Bowers • Lois BrownCarolyn & Paul Brubaker • Nancy H. CanaryDona & Bob Dales • Jeffrey & Karen De HaanGary Garrison • Ruth & Laurence GellerFred & Martha Hardman • Leo Hindery, Jr.Bill & Virginia Ives • J. Willis JohnsonJerry & Judy Kambestad • Elaine KendallDavid M. & Barbara A. Kirr • Phillip & Susan LarsonRuth J. Lavine • Mr. & Mrs. Richard A. LeahyPhilip & Carole Lyons • Richard & Susan MastioCyril & Harriet Mazansky • Michael W. MichelsonJames & Judith Muller • Wendell & Martina MusserBond Nichols • Earl & Charlotte NicholsonBob & Sandy Odell • Dr. & Mrs. Malcolm PageRuth & John Plumpton • Hon. Douglas S. RussellDaniel & Suzanne Sigman • Shanin SpecterRobert M. Stephenson • Richard & Jenny StreiffPeter J. Travers • Gabriel Urwitz • Damon Wells Jr.Jacqueline Dean WitterALLIED NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS_________________________________CHURCHILL CENTRE - UNITED KINGDOMPO Box 1915, Quarley, Andover, Hampshire SP10 9EETel. & Fax (01264) 889627CHAIRMANPaul. H. Courtenayndege@tiscali.co.ukVICE CHAIRMANMichael KelionHON. TREASURERAnthony Woodhead CBE FCASECRETARYJohn HirstCOMMITTEE MEMBERSSmith Benson • Eric Bingham • Robin BrodhurstRandolph S. <strong>Churchill</strong> • Paul H. CourtenayRobert Courts • Geoffrey Fletcher • Derek GreenwellRafal Heydel-Mankoo • John Hirst • Jocelyn HuntMichael Kelion• Michael Moody • Brian SingletonAnthony Woodhead CBE FCATRUSTEESThe Hon. Celia Sandys, ChairmanThe Duke of Marlborough JP DL • The Lord MarlandDavid Boler • Nigel Knocker OBE • David PorterPhilip H. Reed OBE_________________________________________INTL. CHURCHILL SOCIETY OF CANADAwww.winstonchurchillcanada.caAmbassador Kenneth W. Taylor, Honorary ChairmanMEMBERSHIP OFFICESRR4, 14 Carter RoadLion’s Head ON N0H 1W0Tel. (519) 592-3082PRESIDENTRandy Barberrandybarber@sympatico.caMEMBERSHIP SECRETARYJeanette Webberjeanette.webber@sympatico.caTREASURERCharles Andersoncwga@sympatico.ca__________________________________CHURCHILL CENTRE AUSTRALIAAlfred James, President65 Billyard Avenue, Wahroonga NSW 2076Tel. (61-3) 489-1158abmjames@iinet.net.au________________________________________________CHURCHILL SOCIETY FOR THE ADVANCEMENTOF PARLIAMENTARY DEMOCRACYwww.churchill.society.orgRobert A. O’Brien, Chairmanro’brien@couttscrane.com3050 Yonge Street, Suite 206FToronto ON M4N 2K4, CanadaTel. (416) 977-0956

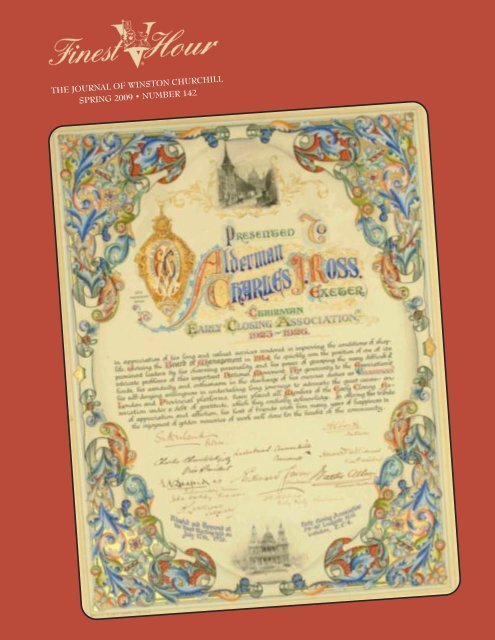

CONTENTSThe Journal of<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>,Number 142SPRING 2009Cover: An illuminated presentation to Alderman Charles Ross, President of the EarlyClosing Association, photographed from his stock by Mark Weber (The <strong>Churchill</strong> BookSpecaliast, www.wscbooks.com). Mr. Weber considers this remarkable item the most beautifulautograph he has ever encountered. Story by Paul Courtenay on page 6.Tolppannen, 16<strong>Churchill</strong>, 28CHURCHILL, CALIFORNIA AND HOLLYWOOD16/ <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> and Charlie ChaplinPerfect Combination or the Original Odd Couple? • Bradley P. Tolppannen22/ Chaplin: Everybody’s Language:He Made the Whole World Laugh • <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>28/ Nature’s Panorama in CaliforniaImpressions of a Traveller, Eighty Years Ago • <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>33/ <strong>Churchill</strong> and OrwellA Gentle Accoldate from One Giant to Another • Robert Pilpel35/ Leading <strong>Churchill</strong> Myths: “<strong>Churchill</strong> Caused the 1943-45 Bengal Famine”Fact: The Blame Rests with the Japanese • Richard M. LangworthCHURCHILL PROCEEDINGS36/ Sheriffs and Constables:<strong>Churchill</strong>’s and Roosevelt’s Postwar World • Warren F. KimballBOOKS, ARTS & CURIOSITIES48/ <strong>Churchill</strong> as a Literary Character • Michael McMenamin49/ Reviews: <strong>Churchill</strong> by Himself • The Last Thousand Days of the British Empire‘Blinker’ Hall, Spymaster • Best Little Stories from the Life and Times of<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> • <strong>Churchill</strong>: The Greatest Briton Unmasked• Reviewed by Manfred Weidhorn, David Freeman, Antoine Capet,Christopher H. Sterling and Michael McMenaminPilpel, 33DEPARTMENTS2/ <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre Administration • 4/ Despatch Box • 5/ Editor’s Essay6/ Datelines • 8/ Around & About • 10/ Leading <strong>Churchill</strong> Myths (16)11/ Official Biography • 12/ Riddles, Mysteries, Enigmas • 14/ Action This Day20/ Wit & Wisdom • 32/ History Detectives • 47/ <strong>Churchill</strong> Quiz54/ Eminent <strong>Churchill</strong>ians: Jay Piper • 62/ Ampersand • 63/ Regional DirectoryCFINEST HoUR 142 / 3

Number 142 • Spring 2009ISSN 0882-3715www.winstonchurchill.org____________________________Barbara F. Langworth, Publisherbarbarajol@gmail.comRichard M. Langworth CBE, Editormalakand@langworth.namePost Office Box 740Moultonborough, NH 03254 USATel. (603) 253-8900Dec.-March Tel. (242) 335-0615___________________________Editor Emeritus:Ron Cynewulf RobbinsSenior Editors:Paul H. CourtenayJames R. LancasterJames W. MullerNews Editor:Michael RichardsContributorsAlfred James, AustraliaTerry Reardon, CanadaAntoine Capet, FranceInder Dan Ratnu, IndiaPaul Addison, <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>,Robert A. Courts,Sir Martin Gilbert CBE,Allen Packwood, United KingdomDavid Freeman, Ted Hutchinson,Warren F. Kimball,Michael McMenamin,Don Pieper, Christopher Sterling,Manfred Weidhorn, United States___________________________• Address changes: Help us keep your copiescoming! Please update your membership officewhen you move. All offices for The <strong>Churchill</strong>Centre and Allied national organizations arelisted on the inside front cover.__________________________________Finest Hour is made possible in part throughthe generous support of members of The<strong>Churchill</strong> Centre and Museum, the NumberTen Club, and an endowment created by the<strong>Churchill</strong> Centre Associates (page 2).___________________________________Published quarterly by The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre,offering subscriptions from the appropriateoffices on page 2. Permission to mail at nonprofitrates in USA granted by the UnitedStates Postal Service, Concord, NH, permitno. 1524. Copyright 2009. All rights reserved.Produced by Dragonwyck Publishing Inc.DESPATCH BOXFORTY YEARS OF FHI have read the thick FortiethAnniversary issue number 140, truly amagnum opus. First, it is a review of agreat journal. Second, it is a review of agreat man. Third, but no less important,it is a tribute to a great editor. Wemembers of The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre and<strong>Churchill</strong> Museum owe our editor atremendous debt of gratitude.DR. CYRIL MAZANSKY, NEWTON CENTRE, MASS.Forty years, and at the helm formost of them! That’s one grand accomplishment,and a huge gift to theliterature over the years. So glad myfavorite cartoonist is on the cover. I wassurprised and tickled to see I’d evenmade the top hundred articles list. Kudosto you and Barbara for all your effortsover the years.PROF. CHRISTOPHER H. STERLINGGEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, D.C.Thank you for yet another fabulousissue of Finest Hour.DAN BORINSKY, LAKE RIDGE, VA.Best Finest Hour ever. The factthat you mentioned me proves it!AL LURIE, NEW YORK, N.Y.Awesome: a great issue with manyfine contributors. Our man would beproud. Thank you for the photo andacknowledgements of Naomi and me.May the cognac and cigar at your appearancein Dallas November 30th bememorable. I’ll be with you and theNorth Texas <strong>Churchill</strong>ians in spirit.LARRY KRYSKE, PLANO, TEX.I just enjoyed a few hours with the40th Anniversary issue of Finest Hour,and all the memories you recalledtherein. Another fine piece of writingand editing. It has been ages since I revisitedthe story of the mysteriousdouble-fleet of trolleys at the 1995Boston conference (page 47). We neversolved that mystery, but we also nevermissed a beat that evening.All this looking back made me alsorecall our many accomplishments, suchas the <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre FoundingMember campaign, the Associatesprogram, the Gregory Peck video toname a few. I cannot imagine FinestHour without you, so for now, I will not.PARKER H. LEE III, LYNCHBURG, VA.FINEST HoUR 142 / 4I spent two days reading FinestHour 140 cover-to-cover. My personalcongratulations on the greatest issue yet.The content was not only uniformlyinteresting, but what I would describe as“smashing!” The issue will be savedamongst my most important publicationsand memorabilia.GARY GARRISON, MARIETTA, GA.In the list of contributors on page78 you indeed forgot a name. (See FH107: 29-33, “Toy Troopers, SmallStatesmen.”) Also, I held together theOmaha chapter with time, talent andtreasure until deterioration of my healthbegan to limit my activities recently, duesand contributions continuing. Keep upthe good work.EDWARD W. FITZGERALD, OMAHA, NEB.Edward, our net slipped when itcame to “Books, Arts & Curiosities,”since those articles weren’t indexed individually.So sorry. We appreciate yoursupport. RMLThe incomparable Finest Hour140 provokes many thoughts. First, aslots of us watch with glee as PresidentBush vacates the White House, let’s consider<strong>Churchill</strong>’s valediction to NevilleChamberlain, quoted in this issue: “Inone phase men seem to have been right,in another they seem to have beenwrong. Then again, a few years later,when the perspective of time has lengthened,all stands in a different setting.”Second, many hands will havebeen wrung by the close of the interregnumbetween 4 November and 20January. Cooperation between the not yetold and the not yet new is seeminglyunprecedented. But not really.As noted by Gordon Walker in“Election 1945: Why <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>Lost,” even when <strong>Churchill</strong> was facingthe voters he brought his opponent (andDeputy Prime Minister) Clement Attleeto the Potsdam conference. The votecount was sandwiched within the conference.When the votes were counted, itwas Attlee not <strong>Churchill</strong> who concludedthe conference, and then the war. Thebrutally tough issues of that day werehanded off seamlessly—and quickly—toa new administration. <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong>’s statesmanship continues toprovide a ready guide. ,SHANIN SPECTER, GLADWYNE, PENNA.

E D I T O R ’ S E S S AYSheet Anchor in “Sterner Days”A<strong>Churchill</strong>ian born in Niagara Falls, New York asked if we knew what <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> was doing on NewYear’s Eve, 31 December 1941. Surprisingly—because we don’t have many accounts of his ninety NewYear’s Eves—we did.On that evening, <strong>Churchill</strong> was hurtling past Niagara Falls itself, en route from Ottawa, where he’ddescribed Britain as a chicken with an unwringable neck, to Washington, where he would resume urgent conversationswith President Roosevelt in the wake of Japan’s onslaught in Asia and the Pacific.As the sweep second hand of “The Turnip,” his beloved pocket watch, counted down the remaining momentsof 1941, <strong>Churchill</strong> called his staff and accompanying newspaper reporters to the dining car of his train. Then, raisinghis glass, as the train rocked and swayed over the tracks, he made this toast:“Here’s to 1942, here’s to a year of toil—a year of struggle and peril, and a long step forward towards victory.May we all come through safe and with honour.”How apposite those words are right now. No, there is no Third Reich, no Imperial Japan—but there are statelessenemies who seek our ruin; there is economic chaos of epic proportions. As our chairman Laurence Geller writes:“People are holding back for fear of the unknown. Unemployment will soon double. This quarter most G-8 economieswill experience a negative GDP. For the year it will almost certainly be negative and next year at best will be flat orinsipid. People are frightened, inventories are diminished, business and consumer confidence is at an all-time low.”What a time for <strong>Churchill</strong>. And there he is, still hoping we will all come through safe and with honour.How often <strong>Churchill</strong> knew exactly what to say! True, he insisted that the British people had the “lion heart,”that he had merely provided the roar; that he had always earned his living by his pen and tongue. What else did theyexpect? Makes no difference. His incandescent words remain. Vivre à jamais dans l’esprit des gens, n’est-ce pas l’immortalité?To live forever in the minds of men, is not that immortality? “When men said to each other, ‘There is noanswer,’” wrote the poet Maxwell Anderson, “You spoke for Trafalgar, and for the sombre lions in the Square.”I cast around for a <strong>Churchill</strong> “quotation of the season” to lead off this edition of Finest Hour: in this season tomark the largest peacetime expansion of government in history, and the arguments swirling around it. I found morethan one. (See next page.)We never proclaim what <strong>Churchill</strong> would think about a modern Act of Congress or Parliament. We haven’tthe foggiest. But we have his words, and as always his words are worth the attention of thoughtful people.Leaders of parties or governments, like Mr. David Cameron, will often inevitably be influenced and encouragedby <strong>Churchill</strong>’s experience: his triumphs and tragedies, his mistakes and failures, for it diminishes <strong>Churchill</strong> toregard him as superhuman. Yet there was nobody like him when it came to communicating the unchanging verities bywhich, as he put it, “we mean to make our way.”We are right to worry over events. And right to remember <strong>Churchill</strong>’s optimism, his determination, hisunswerving faith in the English-Speaking Peoples, in their capacity to come through, safe and with honour.<strong>Churchill</strong> was a fatalist, but never troubled by what he could not control. “One only has to look at Nature,” hewrote his mother from India at the age of 24, “to see how very little store she sets by life. Its sanctity is entirely ahuman idea. You may think of a beautiful butterfly: 12 million feathers on his wings, 16,000 lenses in his eye; amouthful for a bird. Let us laugh at Fate. It might please her.”Mr. Cameron will likely conclude with <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>: “For myself I am an optimist—it does not seem tobe much use being anything else.” There certainly does not seem to be much use in pessimism if you are charged withthe leadership or a country, or a party, or a company, or an institution.And we know Mr. Cameron would agree with the Harrow Old Boy who, on his first visit there since hisschooldays, substituted “sterner days” for “darker days” in a Harrow song verse written for him:“Do not let us speak of darker days; let us rather speak of sterner days. These are not dark days; these are greatdays—the greatest days our country has ever lived; and we must all thank God that we have been allowed, each of usaccording to our stations, to play a part in making these days memorable in the history of our race.” RMLFrom a programme note in a <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre dinner in London for the Rt. Hon. David Cameron MP.FINEST HoUR 142 / 5

DateLinesSEASON’S QUOTES:WSC ON THE “STIMULUS”MARCH 20TH— No, Sir <strong>Winston</strong> hasnot interrupted his first millionyears painting to comment (right)on the U.S. government’s “fiscalstimulus package.” And we’re notgoing to suggest what he wouldthink of it—heaven forbid. Our“Quotations of the Season” areranged without comment inchronological order. Draw yourown conclusions.“NOT MUCH IN THAT...”LONDON, MARCH 1ST— From JohnCharmley to Pat Buchanan, we’ve readthe same story: <strong>Churchill</strong> destroyed theBritish Empire and laid the way forRusso-American hegemony by rejectingRealpolitik and refusing to “do a deal” towind down the war with Hitler after theFall of France.We were reminded that <strong>Churchill</strong>himself was asked that question—afterhis retirement in 1955 while re-readingprivate secretary Sir Anthony MontagueBrowne’s book, Long Sunset (London:Cassell, 1995, 200).<strong>Churchill</strong>’s answer: “You’re onlysaying that to be provocative. You knowvery well we couldn’t have made peaceon the heels of a terrible defeat. Thecountry wouldn’t have stood for it. Andwhat makes you think that we couldhave trusted Hitler’s word—particularlyas he could soon have had Russianresources behind him? At best we wouldhave been a German client state, andthere’s not much in that.” Exactly.Quotations of the Seasonou may, by the arbitrary and sterile act of Government—for, remem-Governments create nothing and have nothing to give but what“Yber,they have first taken away—you may put money in the pocket of one setof Englishmen, but it will be money taken from the pockets of another setof Englishmen, and the greater part will be spilled on the way.”—WSC, BIRMINGHAM, 11 NOVEMBER 1903“Where you find that State enterprise is likely to be ineffective, thenutilise private enterprises, and do not grudge them their profits.”—WSC, GLASGOW, 11 OCTOBER 1906“Every new administration, not excluding ourselves, arrives in power with brightand benevolent ideas of using public money to do good. The morefrequent the changes of Government, the more numerous are the bright ideas;and the more frequent the elections, the more benevolent they become.”—WSC, HOUSE OF COMMONS, 11 APRIL 1927“There are two ways in which a gigantic debt may be spread over newdecades and future generations. There is the right and healthy way; andthere is the wrong and morbid way. The wrong way is to fail to make theutmost provision for amortisation which prudence allows, to aggravate theburden of the debts by fresh borrowings, to live from hand to mouth andfrom year to year, and to exclaim with Louis XV: ‘After me, the deluge!’”—WSC, HOUSE OF COMMONS, 11 APRIL 1927“Squandermania…is the policy which used to be stigmatised by the lateMr. Thomas Gibson Bowles as the policy of buying a biscuit early in themorning and walking about all day looking for a dog to give it to.”—WSC, HOUSE OF COMMONS, 15 APRIL 1929“Democratic governments drift along the line of least resistance, takingshort views, paying their way with sops and doles, and smoothing theirpath with pleasant-sounding platitudes. Never was there less continuity ordesign in their affairs, and yet toward them are coming swiftly changeswhich will revolutionize for good or ill not only the whole economic structureof the world but the social habits and moral outlook of every family.”—WSC, “FIFTY YEARS HENCE,” STRAND, DECEMBER 1931“I do not think America is going to smash. On the contrary I believe thatthey will quite soon begin to recover. As a country descends the ladder ofvalues many grievances arise, bankruptcies and so forth. But one mustnever forget that at the same time all sorts of correctives are being applied,COVER STORYReaders may wonder why <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong> signed this particular presentationto Alderman Charles J. Ross,President of the Early ClosingAssociation, 1923-26.When President of the Board ofTrade (12 April 1908 to 18 February1910) <strong>Churchill</strong> was very active in promotingbetter conditions for shopworkers; among them was “one earlyclosing day a week.” WSC must havebeen inducted by the Early ClosingAssociation (established 1842) in recognitionof his initiative over this matter.“Albert” is undoubtedly HRHThe Duke of York (later King GeorgeVI), who interested himself in industrialrelations; but he would not have beeninvolved with such an Association untilFINEST HoUR 142 / 6much later than 1910, and most probablyfrom about 1923 until 1936.“Sutherland” is likely the FifthDuke of Sutherland (1888-1963), whowas contemporaneously involved withThe Duke of York. He succeeded hisfather in 1913 and was very active inpublic life, holding various governmentposts. He was a member of Baldwin’s

1924-29 government while WSC wasChancellor of the Exchequer, serving asPaymaster General (1925-28) andUnder-Secretary of State for War (1928-29). <strong>Churchill</strong> and Sutherland knew eachother well socially. See Mary Soames,Speaking for Themselves, WSC’s letterfrom the Duke’s Scottish estateDunrobin Castle, dated 19 [18]September 1921; also the link passageabout Marigold immediately above.Edmund Ashworth Radford(1881-1944) was a Unionist MP for twoManchester seats (Salford, South 1924-29, Rusholme from 1933). The onlyother detail I can find is that he was achartered accountant who became seniorpartner of his own firm of charteredand adjustments being made by millions of people and thousands of firms. Ifthe whole world except the United States sank under the ocean that communitycould get its living. They carved it out of the prairie and the forests. Theyare going to have a strong national resurgence in the near future. Therefore Iwish to buy sound low priced stocks. I cannot afford any others.”—WSC TO HIS STOCKBROKER, H.C. VICKERS. 21 JUNE 1932“Change is agreeable to the human mind, and gives satisfaction, sometimesshort-lived, to ardent and anxious public opinion.”—WSC, HOUSE OF COMMONS, 29 JULY 1941“Nothing would be more dangerous than for people to feel cheated becausethey had been led to expect attractive schemes which turn out to beeconomically impossible.”—WSC TO FOREIGN SECRETARY AND OTHERS, 17 DECEMBER 1942I do not believe in looking about for some panacea or cure-all on whichwe should stake our credit and fortunes trying to sell it like a patentmedicine to all and sundry. It is easy to win applause by talking in anairy way about great new departures in policy, especially if all detailedproposals are avoided.—WSC, BLACKPOOL, 5 OCTOBER 1946“The idea that a nation can tax itself into prosperity is one of the crudestdelusions which has ever fuddled the human mind.”—WSC, ROYAL ALBERT HALL, 21 APRIL 1948“Socialism is the philosophy of failure, the creed of ignorance, and thegospel of envy.”—WSC, PERTH, 28 MAY 1948“The choice is between two ways of life: between individual liberty andState domination; between concentration of ownership in the hands of theState and the extension of ownership over the widest number of individuals;between the dead hand of monopoly and the stimulus of competition;between a policy of increasing restraint and a policy of liberating energyand ingenuity; between a policy of levelling down and a policy of opportunityfor all to rise upwards from a basic standard.—WSC, WOLVERHAMPTON, 23 JULY 1949“In America, when they elect a President they want more than a skilfulpolitician. They are seeking a personality: something that will make thePresident a good substitute for a monarch.”—WSC TO LORD MORAN, 19 MAY 1955 ,accountants; whether this involved himwith the Early Closing Association isunclear. —PAUL H. COURTENAYWINSTON IS BACK:(IN EIGHT VOLUMES)LONDON, JANUARY 23RD— The BBCannounced that President Obama sentGeorge W. Bush’s Jacob Epstein bust of<strong>Churchill</strong> packing from the Oval Office(while retaining a bust of AbrahamLincoln), producing a buzz of speculationover the implied symbolism.The bust is one of four or fivecopies sculpted by Jacob Epstein, andregarded as the most valuable of its kindever commissioned. Bush’s was from theBritish government collection atCockburn Street, London; another is atWindsor and others are in private hands.In 2001 President Bush explained: “Myfriend the Prime Minister of GreatBritain heard me say that I greatlyadmired <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> and so hesaw to it that the government loaned methis and I am most honored to have thisJacob Epstein bust....”But zealots soon urged us todemand its return, since in their viewBush was undeserving, or using it to proclaimhimself a <strong>Churchill</strong>. In fact, he wassimply an admirer, like most of us.Plus ça change....Now that the busthas been returned, we are encouraged toprotest its removal.The BBC speculated that Obamawas “looking forward not backward,”while The Daily Telegraph ventured thatthere might be personal reasons: “It wasduring <strong>Churchill</strong>’s second premiershipthat Britain suppressed Kenya’s MauMau rebellion. Among Kenyans allegedlytortured by the colonial regime includedone Hussein Onyango Obama, thePresident’s grandfather.”Diana West exploded that theoryon Townhall.com (http://xrl.us/beipaj) byexplaining that this allegation stems fromObama’s “Granny Sarah” (who alsoclaims that he was born in Kenya, whichwould make him ineligible to bePresident). In Obama’s Dreams of MyFather, West wrote, the President“describes his grandfather’s detention aslasting ‘over six months’ before he wasfound innocent (no mention of torture).Whatever the case, <strong>Churchill</strong> didn’tbecome prime minister for the secondtime until the end of 1951. The MauMau Rebellion didn’t begin until the >>FINEST HoUR 142 / 7

D AT E L I N E SOVAL OFFICE CHURCHILLIANA: The Epstein bust has bitten the dust, but the OfficialBiography has taken its place. The White House now has more <strong>Churchill</strong>iana than ever.end of 1952, one year after Obama’sgrandfather’s release.”But President Obama now hasmore <strong>Churchill</strong>iana than President Bushhad: in a March visit to Washington,British Prime Minister Gordon Brownpresented him with “a first edition of SirMartin Gilbert’s seven-volume biographyof <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>.” (Yes, “sevenvolumes”—Sir Martin was short VolumeV, but Chartwell Booksellers in NewYork City helped him out, and the fulleight volumes were delivered.)Asked for comment by Newsweek,FH’s editor said he read little into thecontroversy: “Mr. Obama admiresLincoln, and it seems perfectly reasonablethat he should have a the bronze totemof his choice in his office. Since theEpstein bust was a loan to a previousPresident, it is unremarkable that a newPresident would wish to return it.President Obama, an intelligent man,probably appreciates that theParliamentary forms finally emerging inKenya stem from the colonial British, asthey do in much of the old Empire,notably India and what <strong>Churchill</strong> calledthe ‘Great Dominions.’ To paraphraseMark Steyn (whose bust will never adornthe Oval Office either), imagine howKenya might have developed if it hadbeen colonized by, say, the Germans,Japanese or Russians.”This will not prevent the mediafrom using <strong>Churchill</strong> to promote sundrypolitical viewpoints. But in the March2nd issue of Newsweek, editor JonMeacham (a fair and balanced <strong>Churchill</strong>Centre trustee) struck what we believe isthe right note: “A long-dead foreignleader, then, has become a kind of partisanfigure. This is unfortunate, for<strong>Churchill</strong> offers one of the great casestudies for any leader in how to buildand maintain public confidence in thebleakest of hours....It is also worth amoment’s reflection on how <strong>Churchill</strong>viewed the duty of a leader in a time ofcrisis, for Obama, perhaps unconsciously,is working within that tradition.”The editor’s own amusement onthis business is in the sidebar below.A CHURCHILL IS BACKLONDON, MARCH 20TH— A <strong>Churchill</strong> willonce again hold dominion over Westminster.Duncan Sandys, Sir <strong>Winston</strong>’s affable35-year-old great grandson who sits asa Conservative councillor on the citycouncil, is a shoo-in as the next LordMayor of Westminster, after he was putforward as the official Tory candidate forthe election in May. Sandys, who servesBUST-OUT, 2013In March an American writer claimed that Obama said of the<strong>Churchill</strong> bust: “Get that blank-blank thing out of here” (but offered noattribution). And a British writer snipped that the cheap CD Obamagave British Prime Minister Gordon Brown doesn’t work on British TV.The media just demonstrates its degenerate irresponsibility infanning non-issues. Fifty years ago a different media would have publishedthoughtful pieces on the future of the US-UK relationship. We arewitnessing the triumph of Britney Spearsthought.The President has more pressing matters of concern, as dowe. So, with acknowledgement to the Daily Telegraph, here is a pasticheon a future “Bust-Out” which might well erupt four years hence.H H HWASHINGTON, FEBRUARY 15, 2013— A bust of Abraham Lincoln, loaned toPresident Obama from the State of Illinois art collection after his inaugurationfour years ago, has now been formally handed back.Where has the Lincoln bust gone? Reporters have tracked it tothe palatial Springfield, Illinois residence of Rod Blagojevich, who wasreinstated as Governor in 2011 after the State Supreme Court ruledthat his 2009 impeachment was unconstitutional, following Blagojevich’stwo-year campaign for redemption on Oprah and Larry King.Lincoln is no hero to Mr. Calhoun, who prefers to quote <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong>, author of the famous alternative history, “If Lee Had NotWon the Battle of Gettysburg.” (FH 103, http://xrl.us/beipam). Now abust of <strong>Churchill</strong>, retrieved from storage at the British Embassy inWashington, has replaced Lincoln’s in the Oval Office.Lincoln, remember, sent General Sherman marching throughCalhoun’s home state of Georgia to defeat the Confederacy. AmongConfederates allegedly imprisoned by the Federals was one AloysiusBeauregard Calhoun, the President’s great-great grandfather.Governor Blagojevich says he will offer another evidence ofIllinois’ esteem to the new President when he meets Mr. Calhoun inWashington this month. One state senator has suggested that, givenPresident Calhoun’s interest in the Civil War era, Mr. Blagojevichshould offer a bust of Stephen A. Douglas, Abraham Lincoln’s leadingopponent during the 1860 Presidential Election. ,FINEST HoUR 142 / 8

on the <strong>Churchill</strong> Memorial Trust Counciland is a grandson of Lord Duncan-Sandys,the former cabinet minister, will be theyoungest person to occupy the role.—TIM WALKER, DAILY TELEGRAPHFREE DEPLORABLE SPEECHCHICAGO, MARCH 6TH— <strong>Churchill</strong> Centrechairman Laurence Geller spoke onCNBC of the “McCarthyism” beingdirected by politicians against conventions(http://xrl.us/beiohf): “Thehyperbole and rhetoric was notched upto gigantic levels during this recent politicaldebate season.....We’ve lost an awfullot of major businesses, and it’s not justthose receiving government bailouts thatare affected, but there’s a general fear ofcriticism by people not only making thebookings but people attending these conference....Thehotel industry lost 200,000jobs last year. We thought if things wentthe same way we’d lose 240,000. Thisyear, since the hyperbole got ratcheted upto these levels, we’re on track to lose350,000, 400,000 jobs. The ripplethrough the economy is gigantic,touching 15 million jobs; lodging andtourism is the third largest retail businessin the country. A colleague and Iattended a conference last week, and wewere joking in the car to the hotel,saying: ‘If the CNBC van is out front,keep driving!’”What has this to do with <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong>? It reminds us what he saidabout free speech, including class warfareagainst the convention business (Houseof Commons, 18 June 1951):“One cannot say that the man orthe woman in the street can be broughtup violently and called to accountbecause of expressing some opinion onsomething or other which is sub judice.They are perfectly entitled to do that.They may say things that aredeplorable—many deplorable things aresaid under free speech.”BEST BOOKS: ADDENDUMIn our “Fifty Best Books [About<strong>Churchill</strong>] in the Last Forty Years” (FH140:22) we inadvertently left out two ofProfessor Paul Addison’s picks of hisfavorites in FH 128. (We also left outMy Early Life because it was by notabout <strong>Churchill</strong>.) Since we warned thatyou omit Addison’s choices at your disadvantage,we hasten to list the two weomitted, along with his remarks:AROUND & ABOUTThe 2009 Finest Hour Re-Rat Award (issuedinfrequently) goes to Senator Judd Gregg(R.-N.H.), who, after accepting nomination asPresident Obama’s Secretary of Commerce, withdrew,saying he could not balance “being in the Cabinet versus myself as anindividual doing my job.” Gregg’s nomination had sewn fear among Republicanswho learned that New Hampshire’s Democratic Governor,John Lynch, would appoint a (liberal) Republican in his place. ThusJudd re-rats. (WSC to private secretary John Colville, 26 January 1941:“Anyone can rat, but it takes a certain amount of ingenuity to re-rat.”kkkkkAlfred James of <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre Australia reports that (moving rightalong) the 1911 Census has just been released in England (www.ancestry.com).No address was “private” in those days: <strong>Churchill</strong> is listed at 33Eccleston Square (17 rooms) with Clementine, Diana and eight servants(cook, nurse, lady’s maid, housemaid, parlourmaid, under-parlourmaid,kitchen maid and hall boy). Ah for the days when help was cheap. Ionce tried <strong>Churchill</strong>’s method of getting two days out of one by copyinghis Chartwell routine: an hour of sound sleep in mid-afternoon, bath, dinner,cinema, work from 11pm to 3am, bed, breakfast at 8am, work in bedall morning, bath #2, lunch, afternoon amble and start over again. Worksfine if you have a staff of fifteen. Barbara Langworth was not amused.kkkkkIran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, dismissed overtures tohis country from President Obama, saying Teheran did not see anychange in policy under the new U.S. administration. “They chant theslogan of change but no change is seen in practice,” Khamenei said inhis speech, broadcast live on state television. “We haven’t seen anychange.” In his video message, Obama said the U.S. wanted to engageIran and improve decades of strained relations.We hear echoes in this of Harold Nicolson’s note to his wife, VitaSackville-West, 1 March 1938 (Nicolson Diaries, I, 328). <strong>Churchill</strong>, hesaid, “spoke of ‘this great country nosing from door to door like a cowthat has lost its calf, mooing dolefully now in Berlin and now in Rome—when all the time the tiger and the alligator wait for its undoing.’” ,• Harbutt, Fraser J. The IronCurtain: <strong>Churchill</strong>, America and theOrigins of the Cold War, 1986, 370pages: “It is no secret that <strong>Churchill</strong> isrevered by many Americans as a philosopher-kingand role model for leadership.Whereas in Britain we see him as a manof the past, he is admired in the U.S. as aguide to the present and the future. Hisunique stature on the western side of theAtlantic owes something his wartimealliance with Roosevelt, but as FraserHarbutt shows in a powerfully arguedbook, the decisive factor was the part<strong>Churchill</strong> played, while he was out ofoffice, in facilitating the entry of theUnited States into the Cold War. Thetipping point was his ‘Iron Curtain’FINEST HoUR 142 / 9speech at Fulton, Missouri in 1946.”• Taylor, A.J.P., editor. <strong>Churchill</strong>:Four Faces and the Man (<strong>Churchill</strong>Revised in USA), 1969, 274 pages: “Thissparkling collection of essays anatomised<strong>Churchill</strong>’s qualities as a statesman (A.J.P.Taylor), politician (Robert RhodesJames), historian (J.H. Plumb), militarystrategist (Basil Liddell Hart) and depressivehuman being (Anthony Storr).Research has moved on since then, but asan analysis of the essential <strong>Churchill</strong> ithas never been surpassed. It founded theBritish school of <strong>Churchill</strong>ians whoadmire him “warts and all.”Many disagree with Anthony Storrthat WSC was “depressive,” except invery old age, since the troubles he saw >>

D AT E L I N E SBEST BOOKS...would depress anybody; or that<strong>Churchill</strong>’s relevance and leadership arenot appreciated outside America. We alsodoubt that <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> had asmuch influence on the U.S. plunge intothe Cold War as Harbutt suggests. (Onthis subject, see the compelling essays inJames W. Muller, editor: <strong>Churchill</strong>’s“Iron Curtain” Speech Fifty Years Later,1999, 180 pages.)A’BLOGGINGWE SHALL GOFEBRUARY 15TH— We were amused by a<strong>Churchill</strong>-derived comment describingthe new digital activity known as “blogging”(personal web logs) and Internetchatrooms: “Never have so many peoplewith so little to say said so much to sofew.” However, some bloggers have interestingangles.Take for example “Amazing Ben”(www.badassoftheweek.com): a 28-yearoldcollege administrator, whose style is,well, different.<strong>Churchill</strong>, Ben says, was known“for his unyielding tenaciousness and hisawesome ability to train killer attackhounds to run up and bite Fascists in thejugular when they weren’t looking…oneof the most badass world leaders of themodern era. This dude was a totallyrighteous asskicker who enjoyed puffingon Cuban cigars, shooting guns, drinkingcopious amounts of booze, and kickingNazis in the ___ ___ with a Size 10steel-toed boot, and he didn’t give a crapabout anything that didn’t further hisgoal of accomplishing one of those fourtasks. He fought hard, partied hard, worea lot of totally awesome suits, and prettymuch always looked like he’d juststepped out of a badass 1930s pulpfiction detective story.”We linked this on our website. Wewere going to reprint Ben’s essay, but weare not so badass. However, we’re glad tosee the use of profanity in <strong>Churchill</strong>’sfavor for a change.ERRATA, FH 140Page 15: Paul Alkon is a Professorof English and American (not French)Literature. Page 48: The photo of MartinGilbert’s walking tour is 1996 (not1999), during the previous <strong>Churchill</strong>Centre Tour of England.PORTSMOUTH, 2001: Patrick Kinna (left) aboard USS <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, with thencommandingofficer Capt. Mike Franken, USN, at the International Festival of the Sea.PATRICK KINNABRIGHTON, MARCH 14TH— <strong>Churchill</strong> wasflying home from the Continent late inWorld War II when his Dakota began tolose power and altitude, and passengersjoked over what to jettison. “It’s no usethrowing you out,” <strong>Churchill</strong> grinned atPatrick Kinna. “There’s not enough ofyou to make a ham sandwich.”Kinna, one of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s keywartime secretaries, and had many fondmemories (see “Eminent <strong>Churchill</strong>ians,”FH 115, Summer 2002; the above wasrelated to Paul Courtenay by Kinna’snephew at the funeral). He was recommendedto <strong>Churchill</strong> by the Duke ofWindsor, whom he had served while theDuke was with the British militarymission in Paris. From 1940 to 1945 histiny, trim figure rarely left the PrimeMinister’s side. Kinna was present whenPresident Roosevelt unexpectedlyencountered <strong>Churchill</strong> emerging from hisbath at the White House. (WSC laterremarked to the King, “Sir, I believe I amthe only man in the world to havereceived the head of a nation naked.”)Patrick Francis Kinna was born insouth London on 5 September 1913. Hisfather had been decorated for his part inthe relief of Ladysmith during the BoerWar. After leaving school Patrick took acourse in shorthand and typing, thenjoined Barclay’s Bank as a clerk whiledeliberating whether to be a journalist ora skating instructor (he had trained withthe ice-skating star Belita).In 1939, Kinna joined the reserves,but because of his skills (he had won theAll-England championship for secretarialspeeds), he was quickly assigned to theIntelligence Corps and sent to Paris asclerk to the Duke of Windsor.As the Germans drew near theywere ordered to evacuate. After a daydestroying secret documents, the Dukewas spirited to safety while Kinna hitchhikedto the coast to find a ship home.Back in England, Kinna got a telephonecall from 10 Downing Street andjoined <strong>Churchill</strong> aboard HMS Prince ofWales, sailing to Newfoundland for theAtlantic Charter meeting with Roosevelt.Kinna’s duties included trying to discouragesailors from whistling—a noise<strong>Churchill</strong> could never abide. But once<strong>Churchill</strong> and Roosevelt got down tobusiness in Argentia Bay there was no letup:“I was terribly busy all the time. Ispent days and days typing.”<strong>Churchill</strong> was so impressed withKinna’s work that he wanted him to joinhis staff. One reason was because, in theearly part of the war, women were notallowed to travel on warships. Kinna wassubstituted, often taking along the worknormally done by Elizabeth Layton,Kathleen Hill and others. From then on,Kinna accompanied <strong>Churchill</strong> on allWSC’s trips abroad.Some accounts suggest that<strong>Churchill</strong> was initially charmed by Stalin,but that was not Kinna’s impression.After their first encounter in Moscow,FINEST HoUR 142 / 10

Kinna recalled <strong>Churchill</strong> storming backto the British Embassy: “I have just had amost terrible meeting with this terribleman Stalin...evil and dreadful,” he began.The British Ambassador interrupted:“May I remind you, Prime Minister, thatall these rooms have been wired andStalin will hear every word you said.”The next morning, though it wasobvious that Stalin had heard, he was“very nice and polite and sweet,” Kinnarecalled: “He couldn’t afford to tell Mr.<strong>Churchill</strong> to buzz off.” Later on, afterWSC’s return from the Yalta conference,Kinna recalled that WSC asked to havehis clothes fumigated, suspecting theyhad acquired some unwelcome residents.<strong>Churchill</strong> had a reputation forbeing brusque and inconsiderate with hisstaff, but Kinna recalled him as “basicallyvery kind,” though if he was in full flight“nothing else mattered and politenessdidn’t come into it.” Secretaries wereinstructed never to ask WSC to repeathimself. As his dictation was fast andfluent, this was difficult, but Kinna madesure repeats were kept to a minimum.After the 1945 election, <strong>Churchill</strong>,now Leader of the Opposition, askedPatrick to stay on, but Kinna had hadenough of long hours—<strong>Churchill</strong> habituallyworked past midnight—anddeclined. Ever magnanimous, <strong>Churchill</strong>wrote a glowing testimonial (“He is aman of exceptional diligence, firmness ofcharacter and fidelity”) and nominatedKinna for an MBE (Member of the MostExcellent Order of the British Empire).The two men kept in touch andalways exchanged white pelargoniums ontheir birthdays. After <strong>Churchill</strong> died,Lady <strong>Churchill</strong> sent a chauffeur toKinna’s home with a present of a set ofelegant tea tables used by her husband.News of Kinna’s skills reached theears of Ernest Bevin, foreign secretary inthe postwar Labour government. “If hewas good enough for <strong>Winston</strong>, he’s goodenough for me,” Bevin is supposed tohave said. Kinna worked with him untilBevin’s death in 1951, and in 1991 hepresented a Douglas Robertson Bissetbronze bust of his former boss to theForeign Office, where it has pride ofplace on the grand staircase.Kinna’s subsequent career was a“bit of an anticlimax.” In the early 1950she joined the timber firm MontagueMeyer, rising to personnel director. Heretired in his sixtieth year and went tolive with his sister Gladys in Brighton,making occasional outings to eventscommemorating the lives of the greatmen for whom he had worked. In 2000he was welcomed on board the USS<strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong> at the InternationalFestival of the Sea in Portsmouth. In2005 he stood alongside HM the Queenat the opening ceremony of the <strong>Churchill</strong>Museum at the Cabinet War Rooms. Healso lectured, donating the fees to charity.SOME EXERPTS ARE FROM THEDAILY TELEGRAPH, 18 MARCH 2009.JOAN BRIGHT ASTLEY“MISS MONEYPENNY”LONDON— JoanBright Astleybore uniquewitness to theinner workingsof the BritishHigh Commandduring World War II, as a key secretaryon <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>’s staff.From 1941 she was responsible fora special information centre in theCabinet War Rooms, supplying confidentialinformation to British commandersin-chief.From 1943, she accompaniedBritish delegations to the key conferencesof the “Big Three.”Her memoir, The Inner Circle(1971), contained eloquent portraits ofAllied leaders. And she was one of threeor four women Ian Fleming used to forma composite Miss Moneypenny, a centralcharacter in his James Bond series.Bright Astley was born inArgentina, one of seven children of anEnglish accountant working for a railwaycompany and his Scottish governess wife.After a period in Spain, Penelope JoanMcKerrow Bright finished her educationin Bristol, did a secretarial course inLondon and worked as a cipher clerk atthe British legation in Mexico City.In 1936 she declined an offer toteach English to the family of the Nazileader Rudolf Hess, in Munich; she alsopassed on a job with Duff Cooper,working on his biography of Talleyrand.On the eve of war, she became personalassistant to Colonel Jo Holland,head of MI(R), a secret war office departmentexploring ways of causing troubleinside enemy-occupied countries.Holland’s staff was small andmostly amateur, but included ColinGubbins, the future head of the SpecialOperations Executive. With Sir PeterWilkinson, another MI(R) recruit, BrightAstley would publish the biographyGubbins & SOE (1993). When SOEreplaced MI(R) in 1940, she remained atthe War Office, assigned to <strong>Churchill</strong>’sjoint planning committee secretariat inthe Cabinet War Rooms beneathWhitehall, London. Calling the rooms“quiet dungeon galleries,” she wrote: “Anoticeboard showed us if it was ‘fine,’‘wet’ or ‘windy’ outside, red or green >>AVAILABLE AGAIN! THE OFFICIAL BIOGRAPHYSupport Hillsdale College in republishing of all past volumes and seven newCompanion volumes. <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong> is already the longest biography ever publishedand the ultimate authority for every phase of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s life.Not only are these books affordable (Biographic volumes $45, Companions $35)but Hillsdale College Press will sell you all eight Biographics for $36 each and alltwenty-one (eventually) Companion Volumes for $28 each by subscription.Better yet, if you subscribe for all thirty volumes, you get the Biographic volumesfor $31.50 and the Companions for $24.50. That includes the upcoming, 1500-pageCompanions to Volume V, first editions of which are trading for up to $1000 each!How can you not afford these books? Order from:www.hillsdale.edu/news/freedomlibrary/churchill.asp or telephone toll-free (800) 437-2268.FINEST HoUR 142 / 11

D AT E L I N E SJOAN BRIGHT ASTLEY...lights if an air raid was ‘on’ or ‘off.’From 1941, she ran, for GeneralSir Hastings Ismay, <strong>Churchill</strong>’s defencechief, an underground information roomwhere commanders-in-chief could perusevital briefing papers in confidence andseclusion.General Archibald Wavell, whobecame a friend, asked in 1942 thatBright Astley go to India to establish asecretariat on the London model.(Wavell, promoted to Field Marshal, wasappointed Viceroy of India in 1943.)Ismay refused and, in 1943, made her anadministrative officer for the British delegationmeeting the Americans inWashington. By the end of the war shehad attended six conferences, includingthose attended by Roosevelt, Stalin and<strong>Churchill</strong> at Teheran and Yalta.Accommodation had to bearranged, offices equipped, passes issued.At Yalta she also had to cope with Sovietofficialdom—and snow. On the journeyto Quebec, General Sir Alan Brooke waspeeved at being allocated a train compartmentabove the wheels; WingCommander Guy Gibson complained:“They’ve taken away my name. It’sDambuster here and Dambuster there.”During the final conference at Potsdam,Joan visited the shattered ruins of Hitler’schancellery in Berlin: “In one passagethere were hundreds of new Iron Crossmedals strewn about the floor....a grimand macabre place, its evil spirit hangingover the grim city it had destroyed.”Joan Astley was appointed OBE(Officer of the Most Excellent Order ofthe British Empire) in 1946. She attributedher singular war career to solidtraining, shorthand skills and luck.But she also possessed independence,integrity and a warm and disarmingpersonality. “For Joan,” wrote GeneralIsmay inside her copy of his memoirs,“who was loved by admirals and liftmenalike—and who made a far bigger contributionto the successful working of thedefence machinery than has ever beenrecognised.”In 1949, she married Philip Astley,a retired army officer who was divorcedfrom the actress Madeleine Carroll. Hedied in 1958. Her son, three grandchildrenand a sister survive her.—THE GUARDIANREPRINTED BY KIND PERMISSION, WITHTHANKS TO ALFRED JAMES.GOSLING UP: “Retire to stud?” <strong>Churchill</strong>later joked. “And have it said that thePrime Minister of Great Britain is living offthe immoral earnings of a horse?”TOMMY GOSLING1926-2008TREMONT, NORMANDY— Jockey TommyGosling will forever be linked with twoother indefatigables of the 20th Century:<strong>Churchill</strong> and his battling grey thoroughbred,Colonist II, the most popularEnglish racehorse of the postwar era.The Scottish jockey rode <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong>’s colt, then a four-year-old, toan astonishing eight victories, six in succession,in the 1950 racing season, to thedelight of WSC and the racing public.(See Fred Glueckstein, “<strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong> and Colonist II,” Finest Hour125, Winter 2004-05).<strong>Churchill</strong> found himself somewhatin the doldrums as Opposition leader,and in 1949 his son-in-law, ChristopherSoames, persuaded him to try the avocationof thoroughbreds, despite the doubtsof WSC’s wife. Clementine wrote to afriend of “a queer new facet in <strong>Winston</strong>’svariegated life. I must say I don’t find itmadly amusing.”<strong>Churchill</strong> forked out £2000 for theFrench-bred thoroughbred and the followingyear, 1950, <strong>Churchill</strong>’s trainerWalter Nightingall enlisted the grittyGosling, who had been UK joint championapprentice jockey of the year in1945. An injury in 1951 forced the battlinggrey’s early retirement to stud.Some political commentators suggestedthat the horse’s popularity helped<strong>Churchill</strong> return to power in 1951, afterhaving suffered a shock defeat to Labourin 1945. Friends thought Colonist II’ssuccess revitalized the Prime Minister,who was 75 when he bought him. Seeingthe great man cheering Colonist homereminded ordinary Britons of his humanside, they believed.Shortly before Gosling died in hisFINEST HoUR 142 / 12retirement home in Normandy, France,he said one of his proudest possessionswas a painting by <strong>Churchill</strong>, with a noteof appreciation for what the jockey andColonist (“II” had long since beendropped by the general public) had doneto brighten his twilight years. <strong>Churchill</strong>,a great admirer of the Scottish regimentsduring the war, said he believed theGosling’s will to win had transmitteditself through the saddle to a horse of thesame nature.In 1956, <strong>Churchill</strong> was one of thefirst to send a message of support toGosling after the jockey’s career almostended in both victory and tragedy on theturf at Leicester Racecourse. He had justwon on a horse called Edison when hewas thrown from the saddle and kickedin the head. There were fears for his lifebut he was back in the saddle withinmonths and his accident was the catalystfor the introduction by the Jockey Club(of which <strong>Churchill</strong> was by then amember) of mandatory hard hats underthe traditional silk caps.Hounded by weight problems,Gosling retired relatively young in 1963at the age of 37, having won 363 of morethan 3000 races he rode. But he went onto become a successful trainer, based atthe Priam Lodge stables in Epsom, forthe next 20 years.He saddled 129 winners, mostmemorably Ardent Dancer in the 1965Irish 1000 Guineas, his only “classic” winas a trainer. As a rider, he had won thesame race on Lady Senator in 1961, hisone “classic” success in the saddle. In1960, he came third in the last “classic”of the season, the St. Leger at Doncaster,on <strong>Churchill</strong>’s horse, Vienna.Thomas Gosling was born in thecotton mill village of New Lanark on theriver Clyde on 24 July 1926. Afterworking as a grocers’ message boy and apetrol pump attendant, he followed hisdream of becoming a jockey and wastaken on as an apprentice at Lambourn,Berkshire, known as the “Valley ofHorseracing.” Gosling retired as a trainerin 1983, going first to Dorking, Surrey,then to Trémont, Normandy, where hebred horses until he died on <strong>Churchill</strong>’sbirthday, aged 82. He is survived by hissecond wife, Valerie (née Vickery), andthree sons.—PHIL DAVISON IN THE FINANCIALTIMES; REPRINTED BY KIND PERMISSION. ,

RIDDLES, MYSTERIES, ENIGMASA<strong>Churchill</strong> was a hero and iconic figureain America, but in Britain heremained a politician, and as such as notuniformly admired. David Stafford wroteabout the relatively equable view of<strong>Churchill</strong> among British citizens in “TrueHumanity,” Finest Hour 140:50.Many believe <strong>Churchill</strong> was “past it”after the war, or by his second administration(1951-55). Sir Martin Gilbert hasargued convincingly that WSC’s efforts tobuild a permanent peace were not those ofa senile has-been.Douglas Hall in “<strong>Churchill</strong> theGreat? Why the Vote will not beUnanimous” (Finest Hour 104) noted: “Bytransferring his allegiance from theConservatives to the Liberals and backagain he was successively at odds with all ofthe people for at least some of the time”(www.winstonchurchill.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=822).Some think of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s lasttwenty years as a coda to his prior life: afterWorld War II, anything would be. The lastten years were a sad time of aging anddecline—but not 1945-55.<strong>Churchill</strong> began as a scintillatingLeader of the Opposition, one of the mosteffective in postwar history. But the mainthing that engaged his interest was a questfor peace in a troubled age. The “IronCurtain” speech at Fulton in 1946 was adecisive moment; so were his speeches onEuropean reunification at Zurich and TheHague. In the early 1950s, the irony ofEisenhower resisting his proposals for ameeting with Stalin’s successors, and thenimmediately meeting with them once WSChad resigned, is a sad story.Recommended reading: MartinGilbert, <strong>Churchill</strong> and America for theEisenhower-and-Russians controversies;Anthony Montague Browne, Long Sunsetfor the personal side; Anthony Seldon,<strong>Churchill</strong>’s Indian Summer, for the mostthorough treatment of the 1951-55 premiership;Martin Gilbert, <strong>Winston</strong> S.<strong>Churchill</strong>, vol. 8, “Never Despair” 1945-1965 for complete detail on everything.Be careful of Lord Moran’s<strong>Churchill</strong>: The Struggle for Survival.Past It After 1945?QI’d be interested in your opinion on the final years of <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong>’s life, from the end of World War II in 1945 to 1965. MyBritish friends think little of them. —Arnold Foster, New York CityMartin Gilbert found that much of whatMoran wrote was not in his diary at thetime. It could only have been made uplater. Jock Colville said: “Lord Moran wasnever present when history was made, buthe was sometimes invited to lunch afterward,”which is perhaps too harsh, butnevertheless succinct.Speaking of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s health, a verygood but often overlooked piece on his firststroke by Michael Wardell is “<strong>Churchill</strong>’sDagger: A Memoir of La Capponcina”(winstonchurchill.org, pageid=1225).QaI am an undergraduate composing aapaper in my British literature classabout the influences of <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>.I have found that he quoted Tennyson in anumber of speeches and writings and amcurious to know if any other authors cometo mind when you think of <strong>Churchill</strong>.Namely when <strong>Churchill</strong> himself wrote inreference to particular styles or quotationsof other authors.—ALLISON HAY, UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMAAaYou ask a good question. He had noaUniversity training and educatedhimself by devouring books his mother senthim when he was stationed in India in1896-97: all of the above authors alongwith Malthus, Darwin and many more.You will find those books enumerated inour “Action This Day” website page(www.winstonchurchill.org, pageid=176.)You can access many sources on ourwebsite “search” engine. As a boy WSCread Walter Scott, George Alfred Hentyand Robert Louis Stevenson. His chiefinspirations were the King James Bible,Shakespeare, Gibbon, Macaulay, Plato,Darwin and Malthus. If you enter thesewords in “search,” on our home page, youwill be led to numerous references.Poets: right about Tennyson--thereare seven “hits” on our site. Also tryClough, Milton, Keats, Byron, Burns,Blake, Thomas Moore, Emerson, Kipling.Also enter “Kinglake” (AlexanderWilliam Kinglake, 1809–91). When askedhow to excel at writing history, <strong>Churchill</strong>once replied, “Read Kinglake.” There areSend your questions to the editorlines in Kinglake’s TheInvasion of the Crimea (1863)which closely prefigure<strong>Churchill</strong>’s style. In an 1898article on British frontier policy inIndia <strong>Churchill</strong> wrote: “I shalltake refuge in Kinglake’s celebratedremark, that ‘a scrutiny so minute as tobring a subject under a false angle of visionis a poorer guide to a man’s judgment thanthe most rapid glance that sees things intheir true proportions.’”“<strong>Churchill</strong> and the Art of theStatesman-Writer,” shows how he strung allthis background together: (winstonchurchill.org,pageid=813).Check the new book of quotations,<strong>Churchill</strong> by Himself. Many quotes ofthese authors are included in <strong>Churchill</strong>’sremarks.Finally, Darrell Holley’s <strong>Churchill</strong>’sLiterary Allusions (MacFarland, 1987) is aninvaluable compendium of hundreds of<strong>Churchill</strong>’s sources, organized by subject,including Shakespeare, RomanticLiterature, Victorian Poets, Macaulay, 19thand 20th century literature, etc. There aremany copies on www.bookfinder.co: thecheapest are listed on Amazon. Althoughpricey, this is an important work.Holley’s largest chapter is on theKing James Bible, which he considers<strong>Churchill</strong>’s “primary source of interestingillustrations, descriptive images, and stirringphrase....For him it is the magnum opus ofWestern civilization.” This is an interestingpoint, because <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> was nota devout observer. Yet he admired the Biblefor its eternal truths and literary quality.Note: Miss Hays’ paper will shortlyappear in Finest Hour. —Ed.HILLSDALE’SOFFICIAL BIOGRAPHYQaWhy did volume IV of the newedition of <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>change its title from The Stricken World toWorld in Torment?AThe titles of all volumes in the newaedition, both narrative and document,are determined by Sir MartinGilbert. It was also Martin’s idea to contrivea new and less confusing numberingsystem for the document volumes.—DOUGLAS JEFFREY, EDITOR, HILLSDALECOLLEGE PRESS, HILLSDALE, MICHIGAN ,FINEST HoUR 142 / 13

1 2 5 - 1 0 0 - 7 5 - 5 0 Y E A R S A G O125 YEARS AGO:Spring 1884 • Age 9“Cannot be trusted to behave...”<strong>Winston</strong> was in what was to be hislast term at St. George’s schooland his record was not improving. Hisreport for March shows the low regard inwhich he was held by the Headmaster:“Diligence. Conduct has been exceedinglybad. He is not to be trusted to doany one thing. He has however notwithstandingmade decided progress. GeneralConduct. Very bad—is a constanttrouble to everybody and is always insome scrape or other. Headmaster’sRemarks. He cannot be trusted to behavehimself anywhere.”By 20 June the Headmaster’sreview was only slightly improved.“General Conduct. Better—but still troublesome.Headmaster’s Remarks. He hasno ambition—if he were really to exerthimself he might yet be first at the end ofthe Term.” <strong>Churchill</strong> left St. George’s atthe end of the Summer Term in 1884,never to return.100 YEARS AGO:Spring 1909 • Age 34“A mind that has influenced...”In early April 1909, <strong>Churchill</strong> had asharp exchange of letters with theConservative MP Alfred Lyttelton, whohe believed had publicly accused him ofleaking Cabinet secrets. Lyttelton deniedthe accusation and claimed in a letter to<strong>Churchill</strong> that newspaper reportsimproperly juxtaposed his comments togive an inaccurate impression. <strong>Churchill</strong>replied that Lyttelton’s comments“might, without the sacrifice of any argumentativeadvantage, have been couchedin a more gracious style. Still since itclearly & specifically repudiates anyintention to make a personal chargeagainst the Ministers whose names youmentioned, I express my thanks for it, &my regrets to have put you to anytrouble.” <strong>Churchill</strong>, however, couldn’tresist a final jab at his formerConservative Party colleagues: “Had itnot been for the sentence to which I havereferred, I should certainly not havewritten to you about your speech. I knowhow hard it is sometimes to find thingsto say....”During this period, <strong>Churchill</strong>’sletters kept his wife informed in somedetail about parliamentary proceedings.On 27 April 1909, when the bill to raisehis salary as President of the Board ofTrade was under consideration, he wroteto her that “the debate last night was poisonous.”The next night went better: “Iwrite this line from the Bench. The TradeBoards Bill has been beautifully received& will be passed without division.A[rthur] Balfour & Alfred Lyttelton weremost friendly to it, & all opposition hasfaded away.” Then <strong>Churchill</strong> turned todomestic matters—the library in theirnew home: “You certainly have made amost judicious selection of carpets & Ientirely approve it. I am not quite convincedupon the stained boards in theLibrary—but it does not press. The workis going on vy well. The bookshelves arebeing put in the cases & the colour isbeing most attractively polished.”On 30 May 1909, <strong>Churchill</strong>attended Army maneuvers with his regimentand, to Clementine, was critical ofwhat he had observed, noting how muchbetter he could have done:I daresay you read in the papers aboutthe Field day. My poor face was roastedlike a chestnut and burns dreadfully.We had an amusing day. There werelots of soldiers & pseudo soldiers gallopingabout, & the 8 regiments ofyeomanry made a brave show. But thefield day was not in my judgment wellcarried out – for on one side theinfantry force was so widely extendedFINEST HoUR 142 / 14by Michael McMenaminthat it could not have been used withany real effect, & on the other themounted men failed to profit by thisdangerous error. These military men vyoften fail altogether to see the simpletruths underlying the relationships ofall armed forces, & how the levers ofpower can be used upon them. Do youknow I would greatly like to have somepractice in the handling of large forces.Later in the same letter, he invitedher to meet his mentor:Bourke Cockran—a great friend ofmine—has just arrived in Englandfrom U.S.A. He is a remarkablefellow—perhaps the finest orator inAmerica, with a gigantic C. J. Foxhead—& a mind that has influencedmy thought in more than one importantdirection. I have asked him tolunch on Friday at H of C & shall goto London that day to get my MoneyResolution on the Trade Boards Bill.But what do you say to coming up too& giving us both (& his pretty youngwife) lunch at Eccleston?75 YEARS AGO:Spring 1934 • Age 59“We might learn something fromyour German friends.”<strong>Churchill</strong> was preoccupied almost exclusivelyduring the spring of 1934 with theCommittee of Privileges investigationinto the question he had raised againstthe Secretary of State for India, SamuelHoare, and Lord Derby, for improperlypressuring the Manchester Chamber ofCommerce to revise evidence it had submittedto the Joint Select Committee onIndian Constitutional Reform. The bulkof the correspondence for this period in

<strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, CompanionVolume V, Part 2, the official biographyby Sir Martin Gilbert, is concerned withthis subject.Notwithstanding this preoccupation,<strong>Churchill</strong> gave a speech in theCommons on 14 March, highly criticalof Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald’sfailed policy of disarmament:False ideas have been spread about thecountry that disarmament meanspeace. The Disarmament Conferencehas brought us steadily nearer—I willnot say to war because I share therepulsion from using that word, butnearer to a pronounced state of ill-willthan anything that could be imagined.So in the end what have we got? Wehave not got disarmament. We havethe rearmament of Germany.<strong>Churchill</strong> then went on to explain howan alliance with a France that had disarmed,as the British government hadurged. would have made it more likely toinvolve Britain in a European conflict:Suppose France had taken the advicewhich we have tendered during the lastfour or five years, and had yielded tothe pressure of the two great Englishspeakingnations to set an example ofdisarmament....what would be theposition today? Where should we be?I honour the French for their resolutedetermination to preserve the freedomand security of their country frominvasion of any kind; I earnestly hopethat we, in arranging our forces, shallnot fall below their example....TheRomans had a maxim, “Shorten yourweapons and lengthen your frontiers.”But our maxim seems to be, “Diminishyour weapons and increase your obligations.”Aye, and diminish the weaponsof your friends.On 21 March, <strong>Churchill</strong> addressedthe necessity of creating a Ministry ofDefense over the three services of theArmy, Navy and the Air Force. Ironically,in doing so, he held up the new Naziregime in Germany as a model to follow:In organizing industry, not only actuallybut prospectively, surely we mightlearn something from our Germanfriends, who are building up anentirely new army and other fightingServices, and who have the advantageof building them up from what iscalled a clean-swept table—starting fairin the respect, unhampered indeed. Ihave been told that they have createdwhat is called a ‘weapon office,’ orWaffenamt, which makes for all thethree arms of the Service which theyare so busily developing. It seems tome that this expression, ‘weaponoffice,’ is pregnant, and that it mightwell enter into and be incorporated inour thought at the present time.During this period, <strong>Churchill</strong> wasalso adding to his reputation as one ofEngland’s most prolific and well-paidjournalists. A list of his published articlesduring the spring of 1934 demonstratesthe range of his interests:“Singapore—Key to the Pacific,”Pictorial Weekly, 24 March 1934.“Penny-in-the-Slot Politics,”Answers, 31 March 1934.“The Greatest Half-Hour in OurHistory,” Daily Mail,13 April 1934.“Fill Up The Empire!,” PictorialWeekly, 14 April 1934.“Have You A Hobby?,” Answers,21 April 1934.“Let’s Boost Britain,” Answers, 28April 1934.“A Silent Toast To William Willet,”Pictorial Weekly, 28 April 1934. (SeeFinest Hour 114 or our website.)“What’s Wrong with Parliament?,”Answers, 5 May 1934.“This Year’s Royal Academy IsExhilarating,.” Daily Mail, 16 May 1934.“Great Deeds that Gave Us theEmpire,” Daily Mail, 24 May 1934.50 YEARS AGO:Spring 1959 • Age 84“The President is a real friend”<strong>Churchill</strong> made plans to visit America.His private secretary, AnthonyMontague Browne, wrote to BernardBaruch: “I should tell you for yourstrictly private information that Sir<strong>Winston</strong> has not been very well, and wewere in doubt as to whether he shouldgo. However, he is determined to visitAmerica again, so that is that! I knowthat you will safeguard him from fatigueas much as possible.”From Washington, <strong>Churchill</strong> wroteto his wife on 5 May:Here I am. All goes well & the Presidentis a real friend. We had a most pleasantdinner last night, & I caught up myarrears of sleep in eleven hours. I amFINEST HoUR 142 / 15<strong>Churchill</strong>, Montague Browne and PresidentEisenhower, May 1959.invited to stay in bed all the morning &am going to see Mr. Dulles afterluncheon. Anthony will send you morenews. I send my fondest love darling.The visit went well and, in a report tothe Foreign Office, Montague Brownewrote: that during the three days spent inthe White House Eisenhower showed anaffectionate care and consideration for Sir<strong>Winston</strong> and spent a great deal of timewith him: “He looked well and seemedalert. He said that he is troubled by deafness,but this was not apparent.”Montague Brown continued:His working day seems to be fromabout half-past eight in the morninguntil luncheon. In the afternoon, whenhe was not with Sir <strong>Winston</strong>, heseemed either to be resting or takinglight exercise.The President spoke with what seemedrelief of the approach of the end of histenure. I do not think that this wasassumed. In general he seemed ratherless than optimistic….At one point heconcluded his remarks about the futureof NATO with approximately thesewords: ‘The big question is, will theWest have the endurance and thetenacity and the courage to keep upthe struggle long enough?’ (Mr.McElroy spoke in rather similar termsto Sir <strong>Winston</strong> and hinted to him thatGreat Britain was not pulling itsweight in defence matters. I did nothear this conversation, but Sir <strong>Winston</strong>said that the sense of it was quiteclear.)To sum up, the President seemedrelaxed, healthy and following a régimethat was light enough to keep him so.His outlook seemed on the melancholyside, and it did not appear that hismind was receptive to ideas differingfrom those he already held. ,

GREAT CONTEMPORARIESCHARTWELL, 19 SEPTEMBER 1931. From left: Mr. Punch, Mary <strong>Churchill</strong>’s pug (known for “committingindiscretions” on the carpet), The Hon Tom Mitford, Clementine’s cousin and great friend of Diana and Randolph, the onlybrother of the Mitford sisters, killed in Burma in 1945; Freddie Birkenhead (Second Earl of Birkenhead) who hadsucceeded his father, <strong>Churchill</strong>’s best friend, the previous year and became a historian and his father’sbiographer; <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>; Clementine <strong>Churchill</strong> (then aged 46), Diana (22), Randolph (20), Charlie Chaplin (46).<strong>Churchill</strong> and ChaplinA PERFECT COMBINATION OR THE ORIGINAL ODD COUPLE?CHAPLIN FIRST THOUGHT CHURCHILL ABRUPT, BUT AFTER A DEBATE ABOUT THENEW LABOUR GOVERNMENT THEY STAYED UP TALKING UNTIL 3 AM.CHURCHILL THOUGHT CHAPLIN “BOLSHY IN POLITICS & DELIGHTFUL INCONVERSATION,” AND WAS CERTAIN HE SHOULD PLAY THE LEAD IN THE NEXT FILMABOUT NAPOLEON—AND IF HE WOULD, WSC PROMISED TO WRITE THE SCRIPT.BRADLEY P. TOLPPANENMr. Tolppanen (bptolppanen@eiu.edu) is a librarian and history bibliographer at Booth Library, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois.FINEST HoUR 142 / 16