Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

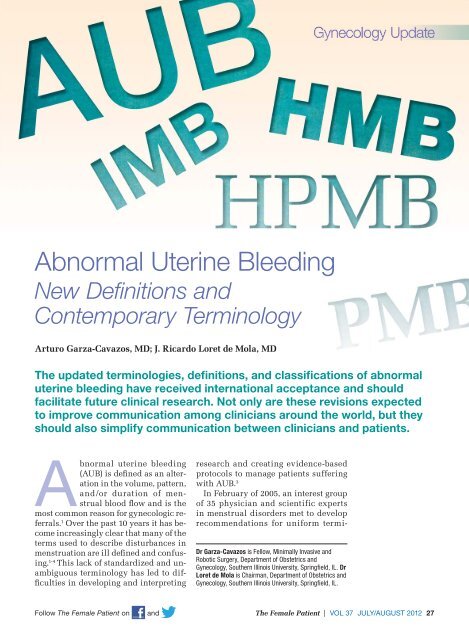

Gynecology Update<strong>Abnormal</strong> <strong>Uterine</strong> <strong>Bleeding</strong>New Defi nitions andContemporary TerminologyArturo Garza-Cavazos, MD; J. Ricardo Loret de Mola, MDThe updated terminologies, definitions, and classifications of abnormaluterine bleeding have received international acceptance and shouldfacilitate future clinical research. Not only are these revisions expectedto improve communication among clinicians around the world, but theyshould also simplify communication between clinicians and patients.<strong>Abnormal</strong> uterine bleeding(AUB) is defined as an alterationin the volume, pattern,and/or duration of menstrualblood flow and is themost common reason for gynecologic referrals.1 Over the past 10 years it has becomeincreasingly clear that many of theterms used to describe disturbances inmenstruation are ill defined and confusing.1-4 This lack of standardized and unambiguousterminology has led to difficultiesin developing and interpretingresearch and creating evidence-basedprotocols to manage patients sufferingwith AUB. 3In February of 2005, an interest groupof 35 physician and scientific expertsin menstrual disorders met to developrecommendations for uniform termi-Dr Garza-Cavazos is Fellow, Minimally Invasive andRobotic Surgery, Department of Obstetrics andGynecology, Southern Illinois University, Springfi eld, IL. DrLoret de Mola is Chairman, Department of Obstetrics andGynecology, Southern Illinois University, Springfi eld, IL.Follow The Female Patient on and The Female Patient | VOL 37 JULY/AUGUST 2012 27

<strong>Abnormal</strong> <strong>Uterine</strong> <strong>Bleeding</strong>: New Defi nitions and Contemporary Terminologynologies and definitions related to AUBfor international use. 2-4 The meeting involveda multistage process that beganwith an assessment of how terms describingabnormal bleeding have beendefined and used to date. This led to anTABLE 1. Recommendations for Discarded Terminology aMenorrhagia Polymenorrhea <strong>Uterine</strong> hemorrhageHypermenorrhea Polymenorrhagia Dysfunctional uterine bleedingHypomenorrhea Epimenorrhea Functional uterine bleedingMenometrorrhagia Epimenorrhagia Metropathica hemorrhagicaaData from Woolcock et al. 4TABLE 2. Accepted Abbreviations DescribingMenstrual Symptoms aAUBHMBHPMBIMBPMB<strong>Abnormal</strong> uterine bleedingHeavy menstrual bleedingHeavy and prolonged menstrual bleedingIntermenstrual bleedingaAdapted with permission from Fraser et al. 7Postmenopausal bleedingexcellent review on historical and currentterminology and definitions forAUB published in 2008 that confirmedthe inconsistent and confusing natureof the clinical terminology pertaining tomenstrual disorders. 4The next step was the organization of aDelphi panel to recommend definitionsand terminologies with potential for internationalagreement. The Delphi panelapproach is a nominal group processdesigned to elicit opinions on a clearlydefined topic and has been used extensivelyto develop clinical guidelines onsuch topics as coronary revascularization,hysterectomy, and colonoscopy. 3The panelists concluded that Englishlanguage terminologies with Greek orLatin roots are poorly defined and createambiguity in meaning and usage.As a result, the panelists recommendedthat much of the current terminologybe discarded (Table 1) and replaced bysimple descriptive terms that could beunderstood by patients and translatedinto most languages (Tables 2 and 3). 5-7Another outcome of the Delphi panelwas an agreement to establish an ongoingstudy group, and the InternationalFederation of Gynecology and Obstetrics(FIGO) was identified as the mostappropriate body to provide supervisionTABLE 3. Recommended Normal Limits for Four Key Menstrual Dimensions(Mid-Reproductive Years) aClinical Dimensions of Menstruation and Menstrual Cycle Cycle Descriptive Terms a Normal Limits (5th–95th percentiles)Frequency of menses (days) Frequent < 24Normal 24–38Infrequent > 38Regularity of menses, cycle to cycle variationover 12 months (days)AbsentNo bleedingRegular Variation ± 2–20IrregularVariation > 20 daysDuration of fl ow (days) Prolonged > 8.0Normal 4.5–8.0Shortened < 4.5aAdapted from Fraser et al. 728 The Female Patient | VOL 37 JULY/AUGUST 2012 All articles are available online at www.femalepatient.com

Garza-Cavazos and Loret de MolaRecommended Terminology, Definitions, and Classificationsof Symptoms of <strong>Abnormal</strong> <strong>Uterine</strong> <strong>Bleeding</strong> aDisturbances of RegularityIrregular Menstrual <strong>Bleeding</strong> (IrregMB): <strong>Bleeding</strong> of > 20 days in individual cycle lengths over a period of 1 year.Absent Menstrual <strong>Bleeding</strong> (amenorrhea): No bleeding in a 90-day period. It was recommended that the term amenorrheabe retained because there is little controversy in its use or defi nition.Disturbances in FrequencyInfrequent Menstrual <strong>Bleeding</strong> (oligomenorrhea): one or two episodes in a 90-day period. It is recommended that the termoligomenorrhea be abolished.Frequent Menstrual <strong>Bleeding</strong>: More than four episodes in a 90-day period (frequent menstruation, not erraticintermenstrual bleeding).Disturbances of Heaviness of FlowHeavy Menstrual <strong>Bleeding</strong> (HMB): Excessive menstrual blood loss that interferes with the woman’s physical, emotional,social, and material quality of life and can occur alone or in combination with other symptoms. The most commonpresentation of AUB.Heavy and Prolonged Menstrual <strong>Bleeding</strong> (HPMB): Less common than HMB. It is important to make a distinctionfrom HMB given they may have different etiologies and respond to different therapies.Light Menstrual <strong>Bleeding</strong>: Based on patient complaint, rarely related to pathology.Disturbance of the Duration of FlowProlonged Menstrual <strong>Bleeding</strong>: Menstrual periods exceeding 8 days in duration on a regular basis, it is commonlyassociated with heavy menstrual bleeding.Shortened Menstrual <strong>Bleeding</strong>: Uncommon, defi ned as bleeding of no longer than 2 days.Irregular Nonmenstrual <strong>Bleeding</strong>Irregular episodes of bleeding, often light and short, occurring between normal menstrual periods. Mostly associatedwith benign or malignant structural lesions, may occur during or following sexual intercourse.<strong>Bleeding</strong> Outside Reproductive AgePostmenopausal <strong>Bleeding</strong> (PMB): <strong>Bleeding</strong> occurring > 1 year after the acknowledged menopause.Precocious Menstruation: Usually associated with other signs of precocious puberty, occurring before 9 years of age.Acute AUBAn episode of bleeding in a woman of reproductive age, who is not pregnant, of suffi cient quantity to require immediateintervention to prevent further blood loss.Chronic AUB<strong>Bleeding</strong> from the uterine corpus that is abnormal in duration, volume, and/or frequency and has been presentfor the majority of the last 6 months.Patterns of <strong>Bleeding</strong>The “shape” of the volume of the bleeding pattern over the days of one menstrual period. It is usually recognized thatabout 90% of the total menstrual fl ow is lost within the fi rst 3 days of the cycle, with day 1 or 2 the heaviest. In womenwith AUB this pattern is variable.aAdapted with permission from Fraser et al. 7The Female Patient | VOL 37 JULY/AUGUST 2012 29

<strong>Abnormal</strong> <strong>Uterine</strong> <strong>Bleeding</strong>: New Defi nitions and Contemporary Terminologyand international credibility. This ledto the formation of the FIGO MenstrualDisorders Group in 2006. 6 After severalimportant publications, the group metfor a pre-congress workshop prior to theFIGO World Congress of Gynecology andObstetrics in October 2009 to review therecommendations. 7 The recommendationswere then presented for approvalthrough an audience responder systemat the FIGO World Congress and weremet with a high level of acceptance. 7The Washington Meeting in 2005 alsodiscussed a future classification systemfor AUB with a primary objective of developingan ongoing process with internationaldebate. 5 The FIGO MenstrualDisorders Group developed an agreementprotocol to recommend a clear andsimple classification system having thepotential for wide acceptance. 6 The systemwas developed with contributionsfrom an international group of bothclinical and nonclinical investigatorsfrom 17 countries. 6,7 The result was thedesignation of the PALM-COEIN ClassificationSystem, which stratifies causesof AUB into nine basic categories and afinal grouping reserved for causes yet tobe classified (see box). 6,8The components of the PALM groupare defined by visually objective structuralcriteria. In contrast, the COEI isunrelated to structural anomalies. TheN group, for entities not yet classified,allows for the addition and modificationof existing classification as new findingson AUB become available and facilitatesThe PALM-COEIN Classification Systemfor Causes of <strong>Abnormal</strong> <strong>Uterine</strong> <strong>Bleeding</strong> aPolyps (AUB-P)Adenomyosis (AUB-A)Leiomyoma (AUB-L) Submucosal/OtherMalignancy (AUB-M)aAdapted with permission from Munro et al. 6Coagulopathy (AUB-C)Ovulatory disorders (AUB-O)Endometrial (AUB-E)Iatrogenic (AUB-I)Not classifi ed (AUB-N)the current or subsequent developmentof subclassification systems. 6,8Components of the PALM-COEINClassification SystemPolyps (AUB-P)Endometrial polyps are a common gynecologiccondition associated withsymptoms of AUB. 8 <strong>Abnormal</strong> vaginalbleeding is the most common presentingsymptom of endometrial polyps andaccounts for all causes of abnormal vaginalbleeding in 39% and 21% to 28%of pre- and postmenopausal women,respectively. 9Polyps are categorized as either presentor absent in the basic classificationsystem. The primary diagnostic approachesinclude noninvasive transvaginalultrasonography (TVUS), withor without 3D imaging and contrast. 9However, other imaging techniques,such as saline infusion sonography andhysteroscopic imaging with or withouthistopathology, may be employed. 6 Hysteroscopicresection should be used forhistopathology. 9There is potential in this category todevelop a subclassification based on variablesthat include size, location, number,morphology, and histology. It is importantto exclude polypoid-appearing endometriumfrom this category since thisfinding may be a normal variant. 6Adenomyosis (AUB-A)Approximately 70% of patients with adenomyosishave symptoms of AUB; 30%have symptoms of dysmenorrhea; and19% present with both. 10 Traditionally,diagnosis has been established withhistopathology after hysterectomy; however,because adenomyosis can be accuratelydetected with ultrasound andmagnetic resonance imaging (MRI), theFIGO system calls for the use of diagnosticimaging. 6,10 Given the limited accessto MRI in some communities, it hasbeen further proposed that ultrasoundimaging criteria comprise the minimumrequirements for assigning a diagnosisof adenomyosis. 630 The Female Patient | VOL 37 JULY/AUGUST 2012

<strong>Abnormal</strong> <strong>Uterine</strong> <strong>Bleeding</strong>: New Defi nitions and Contemporary TerminologyLeiomyomas (AUB-L)<strong>Uterine</strong> fibroids are the most commonbenign tumor of the female genital tract.Age is the most common risk factor, andrecent longitudinal studies have estimatedthe lifetime risk in women overthe age of 45 to be more than 60%. Racealso contributes to risk: the estimatedincidence rates of fibroids by age 50 isgreater than 80% in African-Americanwomen and 70% in white women. Theage-specific incidence of fibroids in African-Americanwomen is 2 to 3 timesmore than white women. 11,12 Additionalfactors associated with increased incidenceare nulliparity, cigarette smoking,and a prolonged menstrual cycle.Fibroids originate from a single cell (themonoclonal origin); however, candidategenes for common uterine fibroids havenot yet been identified. <strong>Uterine</strong> fibroidsFOCUSPOINT‣In the secondary system, differentiationof leiomyomas that are submucosalfrom others is required becauseof the higher association of AUBwith submucosal lesions.can also increase the risk for infertilitydepending on their location, with submucosalfibroids increasing both therisks for infertility and AUB.Primary, secondary, and tertiary classificationsystems have been submitted.Like the classification system for endometrialpolyps, the primary classificationsystem for leiomyomas reflects onlythe presence or absence of one or moreleiomyomas, regardless of location, number,or size. In the secondary system, differentiationof leiomyomas that are submucosal(SM) from others (O) is requiredbecause of the higher association of AUBwith submucosal lesions. The tertiarysystem is based on an adopted design bythe European Society for Human Reproductionand Embryology for subendometrialor submucosal leiomyomas, whichincludes categorization of intramuraland subserosal leiomyomas. Importantly,the tertiary system has great potentialfor both research and clinical use. 6,8Malignancy (AUB-M)The primary symptom of endometrialneoplasia is AUB, which typicallyprompts an endometrial biopsy to ruleout endometrial carcinoma, the mostcommon gynecologic malignancy inthe United States. Approximately 70%of postmenopausal women with abnormaluterine bleeding are diagnosed withbenign findings, 15% with endometrialhyperplasia, and 15% with endometrialcarcinoma. Although the risk ofendometrial carcinoma is much lowerin women of reproductive age, endometrialevaluation is recommended forthose at high risk, such women withchronic anovulation, obesity, Lynch syndrome,or diabetes mellitus. Because oneof the most common risk factors, obesity,is epidemic in the United States and escalatingworldwide, 13,14 the internationalincidence of endometrial carcinoma isexpected to increase in the coming years.There are two different subtypes of endometrialcarcinoma: estrogen-relatedtype 1 (endometrioid), which comprises70% to 80% of newly diagnosed cases,and nonestrogen-related type 2 (eg, papillaryserous and clear cell). Type 1 is relatedto unopposed estrogen stimulation ofthe endometrium. Progesterone inhibitsestrogen-induced proliferation and hyperplasiaby inducing glandular secretoryactivity and decidual transformationof stromal fibroblasts; these secretorycells are then shed during withdrawalbleeding. Hormonal contraceptives, combinedor progesterone only, reduce therisk of endometrial carcinoma. 15The widely used World Health Organization(WHO) system classifies endo-32 The Female Patient | VOL 37 JULY/AUGUST 2012

Garza-Cavazos and Loret de Molametrial hyperplasia according to fourcombinations of glandular crowding andnuclear atypia: simple, complex, simpleatypical hyperplasia, or complex atypicalhyperplasia, although the two atypicalhyperplasias are often classified as one.Approximately 50% of women diagnosedwith endometrial hyperplasia have concurrentcarcinoma. Emerging data indicatethat the long-term risk of developingendometrial carcinoma among womenwith simple or complex hyperplasia isless than 5%, but the risk in atypical hyperplasiasis approximately 30%. 16The classification system is not meantto replace the WHO and FIGO systems forcategorizing hyperplasia or neoplasia. Insteadit has been proposed that premalignantand malignant lesions be classifiedas AUB-M and then subclassified usingthe appropriate WHO or FIGO system. 6Coagulopathies (AUB-C)It is important that coagulopathies areincluded in the classification systemgiven that it has been demonstrated that13% of women with heavy menstrualbleeding (HMB) have a disorder of hemostasisthat may be overlooked duringthe differential diagnosis. Testing for coagulopathiesshould be conducted duringthe workup, and the history shouldinclude simple questions to screen forthe presence of hemostasis disorders. 6Ovulatory Dysfunction (AUB-O)Patients in this category will mostly presentwith unpredictable menses with variableflow, and most are associated withendocrinopathies, such as polycystic ovarysyndrome or hypothyroidism. As withcoagulopathies, ancillary testing shouldbe included in the diagnostic process ofpatients of ovulatory dysfunction. 6,8Endometrial Causes (AUB-E)Most patients in this category will haveregular cycles, normal ovulation, andno definable cause of AUB. If this is thecase, patients will likely present withHMB, which may indicate a disorder ofendometrial hemostasis. Other patientsmay present with intermenstrual bleeding(IMB), which may be secondary toinflammation, infection, or abnormalinflammatory response. Currently, moreresearch is needed to define conditionsin this category, which should be diagnosedby exclusion. 6,8FOCUSPOINTThe updated terminologies, definitions,and classifications of AUB have receivedinternational acceptance and shouldfacilitate future clinical research.Iatrogenic (AUB-I)This category refers to AUB associatedwith the use of IUDs or exogenous gonadalsteroids and other systemic agents thataffect blood coagulation or ovulation. 6,8Not Yet Classified (AUB-N)This category is reserved for entitiesthat are poorly defined and/or not wellexamined. Examples include arteriovenousmalformation and myometrial hypertrophy.With more evidence, entitiessuch as these will likely be placed into anew or existing category. 6,8NotationA notation approach has also been designedto enable categorization, whichshould be especially useful to specialistsand researchers. Because a patientmay be found to have more than one potentialentity contributing to symptomsof AUB, this method addresses all componentsand is similar to the WHO TNMmethod of staging tumors.For example, if a patient is found tohave endometrial hyperplasia and ovulationdysfunction with no other abnormalities,she would be categorized asfollows: AUB P 0 A 0 L 0 M 1 – C 0 O 1 E 0 I 0The Female Patient | VOL 37 JULY/AUGUST 2012 33

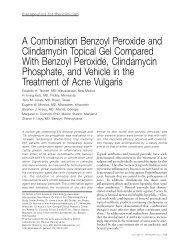

<strong>Abnormal</strong> <strong>Uterine</strong> <strong>Bleeding</strong>: New Defi nitions and Contemporary TerminologyAUBAcuteChronicAncillaryTestingOvulationFunctionDetailed HistoryMedical HistoryMedicationsPhysicalExamAUB – O, I, C, and/or E<strong>Uterine</strong>EvaluationRisk ofMalignancyTVUSEndometrialBiopsyAUB – L, P, or ANormalAUB – MAUB – E or OFIGURE. Flow Chart for Evaluation of <strong>Abnormal</strong> <strong>Uterine</strong> <strong>Bleeding</strong> (AUB). Keep in mind that saline infusion sonography, hysteroscopy,or MRI might be required to diagnose a target lesion after an abnormal transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS). AUB category abbreviations: A,adenomyosis; C, coagulopathy; E, endometrial; I, iatrogenic; L, leiomyoma; M, malignancy; N, not classifi ed; O, ovulatory disorders; P, polyps.Adapted with permission from Munro et al. 6N 0 , with an option to abbreviate as AUB-M;O. If uterine fibroids were present,they would be categorized as AUB L 1(SM)or L 1(O) , depending on the location ofthe leiomyoma. A tertiary classificationof leiomyomas, which is not discussedhere, can be added to further classifythe location of the leiomyoma. 6,8AssessmentPatients with chronic AUB should undergoa structured history and evaluationto determine the underlying factor or factorscontributing to this disorder (see flowchart). As discussed, women with AUBmay have no, one, or multiple identifiablefactors from the FIGO system. The history34 The Female Patient | VOL 37 JULY/AUGUST 2012

Garza-Cavazos and Loret de Molashould determine ovulatory status, potentiallyrelated medical disorders, currentmedications, a screen for disordersof hemostasis, and fertility desires of thepatient. Ancillary testing should includehemoglobin and/or hematocrit, and testingfor conditions that could contribute toovulatory dysfunction.<strong>Uterine</strong> evaluation is guided by thehistory and examination. An endometrialbiopsy is warranted for those patientswith increased risk of hyperplasiaor malignancy. Those patients withrisk of a structural anomaly or who havefailed medical management should undergoimaging with at least a screeningTVUS. Saline infused sonography, hysteroscopy,MRI, (and/or) hysteroscopywith or without biopsy should be usedas indicated if neither TVUS nor endometrialbiopsy is diagnostic or furtherworkup is required. 6,8ConclusionThe updated terminologies, definitions,and classifications of AUB have receivedinternational acceptance and should facilitatefuture clinical research. Not onlyare these revisions expected to improvecommunication between cliniciansaround the world, but they should alsosimplify communication between cliniciansand patients. Importantly, all definitionsand classifications are subject toongoing review and future developmentby the established FIGO Menstrual DisordersWorking Group. This processwill address remaining controversiespertaining to AUB terminology and providea scheduled systematic review ofCoding for <strong>Abnormal</strong> <strong>Uterine</strong> <strong>Bleeding</strong>Philip N. Eskew Jr, MDThis article reviews and evaluates the current terminology associated with the condition of abnormal uterine bleeding andmakes several recommendations for changes. However, as you will see from the ICD-9 codes, many of their suggestionsare already included in the additional defi nitions of the appropriate codes. Many of the suggestions might be included in theICD-10 changes that may be implemented in 2014. For this discussion, the ICD-9 codes mentioned in this article are:626 Disorders of menstruation and other abnormalbleeding from female genital tract626.0 Amenorrhea (primary) (secondary)626.1 Scanty or infrequent menstruation,Hypomenorrhea, Oligomenorrhea626.2 Excessive or frequent menstruation, Heavy periods,Menorrhagia, Menometrorrhagia, Polymenorrhea626.4 Irregular menstrual cycle, Irregular bleeding,Irregular menstruation, Irregular periods626.5 Ovulation bleeding, Regular intermenstrualbleeding626.6 Metrorrhagia, <strong>Bleeding</strong> unrelated to menstrualcycle, Irregular intermenstrual bleeding626.8 Dysfunctional or functional uterine hemorrhage627.1 Postmenopausal bleeding621.0 Polyp of corpus uteri, Endometrium, Uterus617.0 Endometriosis of uterus, Adenomyosis625.3 Dysmenorrhea, Painful menstruation218.0 Submucous leiomyoma of uterus218.1 Intramural leiomyoma of uterus218.2 Subserous leiomyoma of uterus218.9 Leiomyoma of uterus, unspecifi ed182.0 Malignant neoplasm of body of uterus,endometrium621.30 Endometrial hyperplasia, unspecifi ed621.31 Simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia621.32 Complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia621.33 Endometrial hyperplasia with atypia621.34 Benign endometrial hyperplasiaThe procedures mentioned in this article have the followingCPT codes:58100 Endometrial sampling (biopsy) with or withoutendocervical sampling (biopsy), withoutcervical dilation, any method (separate procedure)58555 Hysteroscopy, diagnostic (separate procedure)58558 Hysteroscopy, surgical; with sampling (biopsy)of endometrium and/or polypectomy, with orwithout D & C76830 Ultrasound, transvaginal76831 Saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS), includingcolor fl ow Doppler, when performedDr Eskew is past member, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Editorial Panel; past member, CPT Advisory Committee; past chair,ACOG Coding and Nomenclature Committee; and instructor, CPT coding and documentation courses and seminars.The Female Patient | VOL 37 JULY/AUGUST 2012 35

<strong>Abnormal</strong> <strong>Uterine</strong> <strong>Bleeding</strong>: New Defi nitions and Contemporary Terminologythe classification system, allowing forongoing revisions as recommended.The authors report no actual or potential conflictsof interest in relation to this article.References1. Rahn DD, Abed H, Sung VW, et al. Systematic reviewhighlights diffi culty interpreting diverse clinical outcomesin abnormal uterine bleeding trials. J Clin Epidemiol.2011;64(3): 293-300.2. Fraser IS, Critchley HO, Munro MG. <strong>Abnormal</strong> uterinebleeding: getting our terminology straight. Curr OpinObstet Gynecol. 2007;19(6):591-595.3. Critchley HO, Munro MG, Broder M, Fraser IS. A fi ve-yearinternational review process concerning terminologies,defi nitions, and related issues around abnormal uterinebleeding. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29(5):377-382.4. Woolcock JG, Critchley HO, Munro MG, Broder MS, FraserIS. Review of the confusion in current and historicalterminology and defi nitions for disturbances of menstrualbleeding. Fertil Steril.2008;90(6): 2269-2280.5. Fraser I, Critchley HO, Munro M, Broder M. A processdesigned to lead to international agreement on terminologiesand defi nitions used to describe abnormalitiesof menstrual bleeding. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(3):466-476.6. Munro M, Critchley HO, Fraser I. The FIGO classifi cation ofcauses of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductiveyears. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(7):2204-2208.7. Fraser IS, Critchley HO, Broder M, Munro MG. The FIGOrecommendations on terminologies and defi nitions fornormal and abnormal uterine bleeding. Semin ReprodMed. 2011;29(5):383-390.8. Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, Fraser IS. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormaluterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductiveage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113(1):3-13.9. Salim S, Won H, Nesbitt-Hawes E, Campbell N, AbbottJ. Diagnosis and management of endometrial polyps: acritical review of the literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol.2011;18(5):569-581.10. Garcia L, Isaacson K. Adenomyosis: review of the literature.J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(4):428-437.11. Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM.High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in blackand white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J ObstetGynecol. 2003;188(1):100-107.12. Templeman C, Marshall SF, Clarke CA, et al. Risk factorsfor surgically removed fi broids in a large cohort of teachers.Feril Steril. 2009;92(4):1436-1446.13. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence ofobesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS databrief, no 82. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for HealthStatistics. 2012.14. Berghofer A, Pischon T, Reinhold T, Apovian CM, SharmaAM, Willich SN. Obesity prevalence from a Europeanperspective: a systematic review. BMC Public Health.2008;8:200.15. Mueck AO, Seeger H, Rabe T. Hormonal contraceptionand risk of endometrial cancer: a systematic review.Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(4):R263-271.16. Lacey JV, Sherman ME, Rush BB, et al. Absolute risk ofendometrial carcinoma during 20-year follow-up amongwomen with endometrial hyperplasia. J Clinic Oncol.2010;28(5):788-792.Peer2Peer Webcast on Vulvovaginal Atrophy Is Now Available!Scan this image to watch our newPeer2Peer Webcast, “Innovative Treatmentsfor Vulvovaginal Atrophy,” featuringAssociate Editor Michael L. Krychman, MDCM.In this short video, Dr Krychman interviewsDr James Simon, clinical professorat George Washington University,about the latest research on medicinesbeing developed to be used locally to treat vulvovaginal atrophy.STAY CONNECTEDTHE FEMALE PATIENTFPOTo access this video, you can also text VVA to 25827or go to www.myfpmobile.com/vva.Don’t have a smartphone? No problem!The Webcast is also available online at www.femalepatient.com.36 The Female Patient | VOL 37 JULY/AUGUST 2012