Access to pain relief - World Hospice and Palliative Care Day

Access to pain relief - World Hospice and Palliative Care Day

Access to pain relief - World Hospice and Palliative Care Day

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ContentsKeyForeword1. Introduction1.1 Pain incidence1.2 Opioid analgesics1.3 The importance of being able <strong>to</strong> accesspalliative care, morphine <strong>and</strong> other analgesics1.4 Unavailability of opioids2. Help the <strong>Hospice</strong>s’ survey on access <strong>to</strong>analgesics2.1 Survey results: access <strong>to</strong> analgesics3. Why are opioids not accessible <strong>to</strong>palliative care patients?3.1 National laws3.2 Fear of addiction, <strong>to</strong>lerance <strong>and</strong> side effects 3.3 Poorly developed healthcare systems <strong>and</strong> supply3.4 Expense3.5 Lack of knowledge – healthcare workers, public<strong>and</strong> policy makers4. Essential elements required <strong>to</strong> increaseavailability4.1 Education4.2 Addressing the fears4.3 Accountability4.4 Reviewing laws <strong>and</strong> policies4.5 Strengthening health facilities5. Recent advances in increasing access<strong>to</strong> analgesics5.1 Individuals5.2 WHO <strong>and</strong> INCB 5.3 Resolutions advocating for an increase inaccessibility <strong>to</strong> opioid analgesics5.4 Changes in national laws5.5 Some regional initiatives5.6 Some country initiatives5.7 Proposed projects6. Educational opportunities7. What you can do7.1 Advocacy7.2 Education 7.3 Support for hospices through internationalorganisations <strong>and</strong> directly7.4 Research8. References9. Further resourcesii

WORLD DAY REPORTWith this publication Help the <strong>Hospice</strong>s gives an overviewof the widespread lack of access <strong>to</strong> analgesia. If we donot work <strong>to</strong>gether <strong>to</strong> change this, many of us will discover,sooner or later, what it means <strong>to</strong> need good analgesia; ifwe personally do not encounter this lack of access, wewill watch a relative or a friend that does.In this publication you will find the results of a survey heldamong palliative care workers. The results picture aserious situation. It is noted that the survey population willgive a positive bias of the situation, as palliative careworkers are likely <strong>to</strong> have relatively good access <strong>to</strong>opioids <strong>and</strong> other analgesics compared <strong>to</strong> an averagedoc<strong>to</strong>r.My impression, mainly derived from the per capitastatistics of opioid consumption, is that the situation iseven worse than that found by the survey. The differencesbetween the countries with the highest consumption <strong>and</strong>the remainder of the countries – the large majority – arevery wide. These statistics show that only 10 <strong>to</strong> 15countries have a reasonable per capita consumption, <strong>and</strong>even in these countries underuse for medical reasons areoccasionally reported.For many people, <strong>pain</strong> is part of their daily life. Everyminute they are reminded of it; there is no means ofescape. We can wonder why so many people do not haveaccess <strong>to</strong> analgesia <strong>and</strong> have <strong>to</strong> suffer so much <strong>pain</strong>,when there is an excess of opioids in the world. Onereason is the longst<strong>and</strong>ing fear of drug dependence <strong>and</strong>drug abuse. This fear is, in my view, unfounded. In fact,the relation between drug abuse/drug dependence <strong>and</strong>licit medical use of controlled medicines is weak.More importantly, our countermeasures against thediversion of drugs required for medical use are out ofbalance. Globally, several hundreds of millions of peoplewill require analgesia at least once in their lifetime, whils<strong>to</strong>nly a small fraction of this number misuses opioids.There are restrictions on the h<strong>and</strong>ling of opioids for licitmedical use which aim <strong>to</strong> prevent any possibility ofabuse. However, many countries impose stricterregulations than required by the drug conventions <strong>to</strong> givegood accountability. Yet we know that the source of themajority of opioids used in abuse is from illicit cultivation<strong>and</strong> not from the medical circuit. Furthermore, we knowthat it is quite rare for licit opioid medicines <strong>to</strong> be divertedfor abuse. Although it is important <strong>to</strong> remain on one'sguard, we should not exaggerate but pay attention <strong>to</strong> theside of the balance where the feather is, <strong>and</strong> not <strong>to</strong> theside where the lead weight is already.Fortunately, the international community agrees that weneed change. Both the UN's Economic <strong>and</strong> SocialCouncil <strong>and</strong> the <strong>World</strong> Health Assembly recently acceptedresolutions that have provided the basis for further actionby the <strong>World</strong> Health Organization. I have pleasure <strong>to</strong> workon this, <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> experience strong support from manyindividuals, governments <strong>and</strong> also NGOs such as Helpthe <strong>Hospice</strong>s. They are in support of improving cancercare, HIV care <strong>and</strong> palliative care for all.Together we have a strong case, <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong>gether we will beable <strong>to</strong> make the change.Dr Willem ScholtenTechnical OfficerDepartment of Medicines Policy <strong>and</strong> St<strong>and</strong>ards<strong>World</strong> Health Organizationv

Oral morphine <strong>and</strong> oral methadone:are ‘strong’ opioid analgesics (<strong>pain</strong> relieving drugs);have been proven <strong>to</strong> be very effective analgesics,wholly or partly relieving most types of <strong>pain</strong>;are cheap;are both established medicines with known,predictable <strong>and</strong> preventable side effect profiles;have a wide therapeutic index – the range of dosesover which they can be effective without being <strong>to</strong>xicis exceptionally large; therefore doses can beindividualised easily;are easy <strong>to</strong> administer;are easy <strong>to</strong> adjust (doses) for each individual <strong>and</strong> ifanalgesic requirements change.Oral morphine has been included on the WHO EMLsince 1985. (11)Essential medicines are intended <strong>to</strong> be available:at all times in adequate amountsin the appropriate dosage formswith assured qualityat a price the individual <strong>and</strong> communitycan afford. (12)The WHO EML guides countries as <strong>to</strong> the drugs <strong>to</strong>include in their own essential medicines list, takingaccount of disease prevalence. (13)Essential medicines are those that satisfy the priorityhealthcare needs of the population. (12)Many patients are unable <strong>to</strong> access morphine,methadone or an equivalent opioid.Based on INCB reports, the WHO estimated in2006 (14) :80% of cancer patients have no access <strong>to</strong>the <strong>pain</strong> relieving drugs required~7% of all people in the world will sufferfrom cancer <strong>pain</strong> that can be treated, but willnot be treated.** Based on 80% of world population having no access <strong>to</strong>analgesia, 12% of all death causes being from cancer <strong>and</strong>70% of cancer patients suffering <strong>pain</strong> – (0.8 x 0.12 x 0.7) x100 = ~ 7%.4

WORLD DAY REPORT1.3 The importance of being able<strong>to</strong> access palliative care,morphine <strong>and</strong> other analgesicsAt the age of 21, Mr AB was diagnosed with a giant celltumour <strong>and</strong> underwent a midtarsal amputation in 1979.When it recurred, in 1985, he went through an abovekneeamputation. He was able <strong>to</strong> have a reasonablequality of life with an artificial limb until 1992 when thedisease recurred. He was in <strong>pain</strong>; radiotherapy helpedonly briefly.His severe <strong>pain</strong> meant he lost his means of livelihood<strong>and</strong> life became a huge burden. He had <strong>to</strong> send threeof his four children <strong>to</strong> an orphanage.He was one of the first patients in the Pain <strong>and</strong><strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Clinic (PPCS) when it opened in 1994 inCalicut Medical College. By then Mr AB had been in<strong>pain</strong> for about two years. In the PPCS he was startedon oral morphine <strong>and</strong> other medication. His <strong>pain</strong> wassoon relieved. PPCS found him a livelihood by installinga coffee-vending machine in the hospital. It brought themeans not only <strong>to</strong> get his children back from theorphanage but also <strong>to</strong> allow them all <strong>to</strong> be educated.His disease is slowly progressive. His morphinerequirement slowly went up <strong>to</strong> finally reach 1,000mg aday, <strong>and</strong> at that time a pathological fracture in his femurwas found. Excision of the fractured bone broughtdown the <strong>pain</strong> <strong>and</strong> since 1999 (ie for the last sevenyears), his <strong>pain</strong> has been well controlled on a steadydose of 600mg of morphine a day.He is 48 now. Recently he had a single fraction ofpalliative irradiation <strong>to</strong> the stump which has ulcerated.He is <strong>pain</strong> free on morphine <strong>and</strong> is able <strong>to</strong> work frommorning <strong>to</strong> evening. His eldest son has a job <strong>and</strong> theother children are continuing their education.Case study provided by Prof M. R. Rajagopal,Chairman, Pallium, India5

JM is 33 year old male with Kaposi’s Sarcoma, acancer occurring more frequently in HIV patients. Hehas a huge woody oedema<strong>to</strong>us left leg. JM was one ofthe first cancer <strong>and</strong> HIV/AIDS patients <strong>to</strong> join the NdiMoyo <strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong> programme, Malawi, in August2006.However, he enrolled with me as a patient long beforethe Centre opened. JM lives with his wife <strong>and</strong> their fourchildren. They are very poor <strong>and</strong> at first JM was living indenial of his condition.JM noticed the swelling of his left leg in 1999 <strong>and</strong> went<strong>to</strong> traditional healers. His leg got worse. In 2000 hevisited Salima District Hospital where Kaposis Sarcomawas diagnosed. As he did not get <strong>relief</strong> from hissymp<strong>to</strong>ms, he alternated between the hospital <strong>and</strong>traditional healers until Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2002, when a friendreferred him <strong>to</strong> me for <strong>pain</strong> <strong>relief</strong> at the Salima Parishhome based care clinic where I was working as avolunteer nurse.He presented with moderate burning <strong>pain</strong>s, bone <strong>pain</strong><strong>and</strong> extensive fungal infections. These were managedwith amitriptyline 12.5mg bd, ibuprofen 400mg tds <strong>and</strong>antifungals with good effect. At this time he was testedHIV positive. We controlled his <strong>pain</strong> well <strong>and</strong> treatedopportunistic infections until February 2004, when hedeveloped severe <strong>pain</strong> <strong>and</strong> blisters all over his left leg.As a result he became one of the very first patients inSalima <strong>to</strong> be given morphine, which he was only able <strong>to</strong>access from ‘Lighthouse’ in Lilongwe (over 100km fromhis home).He started on 5mg of oral morphine every four hourswith 10mg at night. He responded well <strong>and</strong> is atpresent <strong>pain</strong> free on oral morphine (7.5mg four hourlywith 15mg at night). For a couple of months the doseneeded <strong>to</strong> be increased <strong>to</strong> 10mg four-hourly <strong>and</strong> 20mgat night. Throughout he has continued <strong>to</strong> haveibuprofen, <strong>and</strong> since July 2004 has had free ART.<strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> analgesia <strong>and</strong> palliative care has reallybenefited JM; he is one of very many in Malawi whowould benefit if they were able <strong>to</strong> access it. Besidesmedical treatment, we have provided him <strong>and</strong> his familywith emotional support <strong>and</strong> used a comfort fund <strong>to</strong>assist them with transport <strong>and</strong> food at times of need. Inaddition, after a long advocacy fight by us, he <strong>and</strong> hisfamily now benefit regularly from food aid distributed bythe <strong>World</strong> Food Programme. He is now happy, able <strong>to</strong>walk, cycle, able <strong>to</strong> take care of his family, <strong>and</strong> wecontinue <strong>to</strong> travel with them on his journey.Case study provided by Lucy Finch, Nurse <strong>and</strong>Founder of Ndi Moyo <strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Centre, Malawi.6

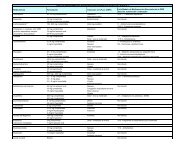

WORLD DAY REPORT10090807060Graph 3: <strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> ‘weak opioids’always availablealways availableThe availability of ‘weak opioids’ was markedlydecreased in Africa compared <strong>to</strong> Asia <strong>and</strong> LatinAmerica.Note: In some places ‘weak opioids’ are expensive <strong>and</strong>hence the step of using a weak opioid is substitutedwith a smaller dose of a strong opioid. This isacceptable practice.% 50403020always availablenever available10 never availablenever available0Africa Asia Latin AmericaTwenty-five per cent of African <strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong>Services never have a weak opioid available.Between 25 – 35% in Latin America <strong>and</strong> Asia donot ‘always’ have a weak opioid available.always availableavailable most of the timeavailable half of the timeoccasionally availablenever available11

%100%90%80%70%60%50%40%30%20%always availableGraph 6: <strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> one or more ‘strong opioids’never availablealways availablealways availablenever available10% never available‘Oral or patch strong opioids’ included tablets,solution, normal <strong>and</strong> slow release preparations of:oral morphineoral methadoneoxycodonehydromorphonefentanyl patches<strong>and</strong> an option for ‘other’.Pethidine was excluded from the analysis as it isnot recommended in chronic <strong>pain</strong> <strong>relief</strong> owing <strong>to</strong><strong>to</strong>xicity following accumulation.Over 20% of palliative care providers in Africacan never access a ‘strong opioid’.0Africa Asia Latin Americaalways availableavailable most of the timeavailable half of the timeoccasionally availablenever availableThirty-five per cent of palliative care providers inLatin America <strong>and</strong> 25% in Asia cannot alwaysaccess any ‘strong opioids’.14

WORLD DAY REPORT%Graph 7: <strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> NSAIDs100 always available always available90always availablealways available8070always available605040always availableGraphs 7, 8, 9 <strong>and</strong> 10 illustrate the overall results forthe availability of some of the other recommendedanalgesics. The variation in access <strong>to</strong> different drugssuggests multiple reasons for lack of access.The current WHO EML (13) includes one NSAID,ibuprofen.The ‘expert committee’ has recommended <strong>to</strong> theWHO that the next revision of the EML shouldinclude two NSAIDs. (16)NSAIDs do differ in properties, effectiveness <strong>and</strong>side effects. It is not known how <strong>to</strong> predict whichNSAID a <strong>pain</strong> will be relieved by.302010never availablenever availableNeveravailable0Availability of Availability of an Availability of Availability of Availability of Availability of anOne NSAID alternative NSAID One NSAID alternative NSAID One NSAID alternative NSAIDAfrica Africa Asia Asia Latin America Latin Americaalways availableavailable most of the timeavailable half of the timeoccasionally availablenever available15

16100%90%80%70%60%%50%40%alwaysavailableGraph 8: <strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> neuropathic analgesicsalways availablealwaysavailablealwaysavailableavailable mos<strong>to</strong>f the timeavailable halfof the timeoccasionallyavailable30% neveravailable20%10%0%neveravailablenever availablenever availableTricyclic Antidepressant Carbamazepine, Pheny<strong>to</strong>in or Sodium Dexamethasone tabs or injValproate‘Neuropathic <strong>pain</strong>s’ covers a wide spectrum: someTherespond better <strong>to</strong> tricyclics whilst others respond better<strong>to</strong> anticonvulsants. No significant difference has beenshown between different tricyclic antidepressants <strong>and</strong>different anticonvulsants in the control of neuropathic<strong>pain</strong> (with the exception of increased effectiveness ofgabapentin compared <strong>to</strong> tricyclics in post herpetic(18, 19)neuralgia).tricyclic amitriptylline <strong>and</strong> the anticonvulsantscarbamazepine, pheny<strong>to</strong>in <strong>and</strong> sodium valproate areon the current WHO EML; all have different significantside effect profiles <strong>and</strong> drug interactions. Note: opioidscan also be very effective in relieving some neuropathic<strong>pain</strong>s. Opioids can be used in conjunction withtricyclics, anticonvulsants <strong>and</strong> dexamethasone.Thirty-seven per cent of palliative care units donot have a constant supply of any drug from the‘anti-convulsant class’.Nearly 30% do not have a constant supply of oneof the tricyclics.Twenty five per cent do not have a constantsupply of dexamethasone.Twelve per cent never have access <strong>to</strong> ananticonvulsant.Dexamethasone is useful for relieving a numberof symp<strong>to</strong>ms common in palliative patientsincluding:<strong>pain</strong> – especially nerve compression <strong>pain</strong><strong>and</strong> liver capsular <strong>pain</strong>aphthous ulcersraised intracranial pressurespinal cord compressionintestinal obstructionureteric obstructionlarge airway obstructionsuperior vena cava obstructioncerebral tumourshypercalcaemia in lymphomasweating <strong>and</strong> hot flushes.It can also act as an:antiemeticappetite stimulant.The current WHO EML (13) recommends only theinjectable form of dexamethasone; the ‘expertgroup’ advised the addition of the tablets. (16)

WORLD DAY REPORT100%90%80%70%Graph 9: <strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> gabapentinneveravailablealways availableGabapentin was included in the recommended list ofpalliative care drugs <strong>to</strong> be added <strong>to</strong> the WHO EML. (16)It has not been proved <strong>to</strong> be more effective than otheranticonvulsants for neuropathic <strong>pain</strong> (except postherpetic neuralgia) but is usually better <strong>to</strong>lerated, withfewer side effects <strong>and</strong> drug interactions. Its cost is likely<strong>to</strong> be a fac<strong>to</strong>r decreasing access.60%% 50%40%always available30%20%neveravailablenever available10% alwaysavailable0%Africa Asia Latin Americaalways availableavailable most of the timeavailable half of the timeoccasionally availablenever available17

100%90%80%70%alwaysavailableGraph 10: <strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong> other analgesicsalwaysavailablealways availableGraph 10 illustrates the availability of some of the otheranalgesics currently on (diazepam <strong>and</strong> paracetamol),or recommended <strong>to</strong> be on (hyoscine), the WHOEML. (13, 16) Baclofen is included as it is effective formuscle spasm in a similar way <strong>to</strong> diazepam but hasfewer side effects.60%Seven per cent of palliative care units never haveaccess <strong>to</strong> paracetamol (acetaminophen).%50%40%30%20%10%never availableNeveravailableneveravailable0Hyoscine tabs or inj Oral Diazepam or Baclofen Paracetamol/ Acetaminophenalways availableavailable most of the timeavailable half of the timeoccasionally availablenever available18

WORLD DAY REPORT3. Why are opioids notaccessible <strong>to</strong> palliativecare patients?Help the <strong>Hospice</strong>s surveyed palliative care providers <strong>to</strong>ask why they felt oral morphine* was not accessible <strong>to</strong>their patients (responses from 69 HCWs all in differen<strong>to</strong>rganisations): 24 in Asia; 28 in Africa; <strong>and</strong> 17 in LatinAmerica).Reasons for the lack of availability could becategorised as:1. Excessively strict national laws <strong>and</strong> regulations.2. Fear of addiction, <strong>to</strong>lerance <strong>and</strong> side effects.3. Poorly developed healthcare systems <strong>and</strong> supply.4. Lack of knowledge – HCWs, public <strong>and</strong> policymakers.* Oral morphine was used in the questions on reasons for lack ofaccess, but it is assumed that many of the reasons are equallyapplicable <strong>to</strong> oral methadone <strong>and</strong> other ‘strong/step 3’ opioids.19

3.1 National laws100%90%80%70%60%%50%Graph 11: Fac<strong>to</strong>rs decreasing access: laws <strong>and</strong> regula<strong>to</strong>ry barriersIn some countries laws governing the h<strong>and</strong>ling ofmorphine <strong>and</strong> other controlled drugs are impractical orso stringent that they prevent HCWs using morphinewhen they feel it appropriate. These laws were aimedat preventing misuse; they were adopted prior <strong>to</strong>advances in knowledge about <strong>pain</strong> <strong>and</strong> opioids, <strong>and</strong>were not intended <strong>to</strong> block <strong>pain</strong> <strong>relief</strong>. Other surveyshave also highlighted this. (20)40%30%20%10%0%Africa Asia Latin AmericaStrict laws <strong>and</strong>/or complex Strict laws <strong>and</strong>/or complex Lack of HCWs ableprocedures required <strong>to</strong> procedures required for <strong>to</strong> prescribeimport, manufacture, prescribing/dispensing oral <strong>and</strong>/or dispensedistribute or s<strong>to</strong>re oralmorphinemorphine20

WORLD DAY REPORT1. Process requires several forms, speciallicenses <strong>and</strong>/or authorisation stamps whichare time consuming <strong>and</strong>/or difficult <strong>to</strong>acquire <strong>and</strong> thus deter HCWs fromprescribing opioids.“<strong>Palliative</strong> care doc<strong>to</strong>rs have a right <strong>to</strong> prescribemorphine but cannot obtain it if they work in ahospice which is not registered in the MoH as amedical organisation.”“Drug companies are not willing <strong>to</strong> import oralmorphine solution as they will not make enoughprofit due <strong>to</strong> spending months on legal papers.”“I waited nearly one <strong>and</strong> a half years <strong>to</strong> get myfirst licence <strong>to</strong> prescribe oral morphine.”“Licences are hard <strong>to</strong> obtain. This is <strong>to</strong> ensurethat only genuine companies are allowed <strong>to</strong>import morphine as a way of ensuring that thereis no misuse, <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> ensure that the accountingbodies <strong>to</strong> INCB are not so many from onecountry.”“Licences are hard <strong>to</strong> obtain. You need <strong>to</strong> writean exam then apply for a licence.”“Bureaucracy for collecting morphine delayswork in the hospitals <strong>and</strong> centres.”“A supply of opioids is now available in thecentral medical s<strong>to</strong>res but many practitioners areunaware, <strong>and</strong> even some of those who have theinformation have not accessed it as they areunwilling <strong>to</strong> follow the due process, which theyregard as tedious.”21

2. Length of supply allowed is short requiringrepeated journeys – which are potentiallyexpensive, a long way <strong>and</strong> difficult when ill– <strong>and</strong> repeated consultations with alreadybusy doc<strong>to</strong>rs.a. In Honduras only a three day supply of oralmorphine is dispensed.b. In Malawi only three days supply of analgesics aredispensed.c. Until the recent review of Romanian law, doc<strong>to</strong>rscould only prescribe three days supply of morphine(for a small number of specified diseases specialauthorisation from a government consultant could beobtained for ‘long term prescribing’ allowing 10 – 15days supply on a repeated basis for threemonths). (20)d. In Israel, unless the doc<strong>to</strong>r confirms that the patientlives far from a pharmacy, supply can only be givenfor 10 days at a time. Opioids are only available frompharmacies with Health Sick Insurance. In someareas there are few or no pharmacies with HealthSick Insurance, meaning patients have <strong>to</strong> travel along way for a few days supply. In addition, if any ofthe details required are omitted by mistake, thepharmacist will send the patient back <strong>to</strong> the doc<strong>to</strong>r,which, when distances are far <strong>and</strong> patients’ are ill,can deter patients from obtaining their drugs.3. A maximum dose is stipulated. This doesnot account for patient variability <strong>and</strong> thefact that there is no maximum dose ofmorphine.a. Until reviewed recently, the Romania pharmacopeiastipulated that no more than 60mg per day should(20, 21)be prescribedb. Drug laws in Israel state that no more than 60mg perday can be prescribed for non-cancer patients(confirmation that patient has cancer needs <strong>to</strong> be onprescription).4. Lack of HCWs qualified <strong>to</strong> prescribecontrolled drugs.a. In Honduras, Tamil Nadu, Mongolia, Peru <strong>and</strong>Kyrgyzstan only specialist palliative care <strong>and</strong>/oroncology doc<strong>to</strong>rs are allowed <strong>to</strong> prescribe morphine.b. In the Philippines only doc<strong>to</strong>rs with two speciallicences are able <strong>to</strong> prescribe morphine.c. Seventeen per cent of countries/regions werereported <strong>to</strong> require specific licences which were hard<strong>to</strong> obtain before being allowed <strong>to</strong> prescribemorphine.d. In Malawi (where clinical officers <strong>and</strong> doc<strong>to</strong>rs canprescribe opioids) there is only one doc<strong>to</strong>r for every100,000 people. (22) Prior <strong>to</strong> a recent amendment,Ug<strong>and</strong>an laws allowed only doc<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> prescribeopioids; in rural communities there is only onedoc<strong>to</strong>r for 50,000 people. Therefore, most peopleare unable <strong>to</strong> access a doc<strong>to</strong>r. These figurescompared <strong>to</strong> 164 doc<strong>to</strong>rs per 100,000 in the UK,where since May 2006 specialist nurses canprescribe opioids in addition <strong>to</strong> doc<strong>to</strong>rs.5. Lack of HCWs able <strong>to</strong> dispensecontrolled drugs.a. Ug<strong>and</strong>an law allows only pharmacists <strong>to</strong> dispenseoral morphine. In 2000 there were only 19pharmacists outside the capital (ie 19 pharmacists <strong>to</strong>cover a population of just over 21million). (23)b. In the Philippines only pharmacists with S3 licensesare allowed <strong>to</strong> dispense oral morphine.22

WORLD DAY REPORT3.2 Fear of addiction, <strong>to</strong>lerance<strong>and</strong> side effects100%90%80%70%% HCWs60%felt r eason 50%for40%decr esed30%access20%10%0%Graph 12: Fac<strong>to</strong>rs decreasing access: fears of addiction, <strong>to</strong>lerance or side effectsAfrica Asia Latin AmericaThe main reasons HCWs felt that oral morphine is notavailable are owing <strong>to</strong> fears of addiction, <strong>to</strong>lerance<strong>and</strong>/or other side effects. In Africa over 50% felt tha<strong>to</strong>ther HCWs fear their patients will become addicted ifgiven oral morphine. A high percentage also felt thatHCWs fear accusation of misusing morphine if theyprescribe/dispense it. The reasons why these shouldnot be feared are addressed on pages 30 – 33.Patients fear addiction HCWs fear diversion <strong>to</strong> HCWs fear accusation ofnon-medical use by ‘public’misuse/harmful use if foundh<strong>and</strong>ling morphineRelatives/carers fear addiction Policy makers fear diversion Fear of <strong>to</strong>lerancetreatments<strong>to</strong> non-medical use by HCWsHCWs fear addiction by patient Policy makers fear they will end Fear of side effectsup with wrong person <strong>and</strong>/or(excluding addiction <strong>and</strong>misuse/harmful use by ‘public’ <strong>to</strong>lerance)“Pharmaceuticals do not want <strong>to</strong> produce theirown morphine due <strong>to</strong> myths <strong>and</strong> ignorance.”“Patients fear its (morphine) use, because itsuse is related with close end stage of life.”“Patients <strong>and</strong> relatives fear use of morphinethinking death is near.”23

3.3 Poorly developed healthcaresystems <strong>and</strong> supply% HCWs100%90%80%70%60%50%Graph 13: Fac<strong>to</strong>rs decreasing access:poor access <strong>to</strong> healthcarePoor access <strong>to</strong> health centres/doc<strong>to</strong>rsowing <strong>to</strong> distancePoor access <strong>to</strong> health centres/doc<strong>to</strong>rsowing <strong>to</strong> expensePoor access <strong>to</strong> health centres/owing <strong>to</strong>preference for traditional/local medicines, treatmentsIn some areas, lack of access <strong>to</strong> morphine simplyreflects the difficulty for numerous people <strong>to</strong> accesshealth facilities. The lack of HCWs able <strong>to</strong> prescribe <strong>and</strong>dispense opioids is discussed under ‘national laws’(pages 20 – 22) This was felt <strong>to</strong> be more of a problemin Africa <strong>and</strong> Latin America than Asia – which is alsoreflected in the availability of some of the non-opioiddrugs, eg NSAIDs. Comparing the availability ofNSAIDs with the strong opioids indicates that this isnot the only fac<strong>to</strong>r, as access <strong>to</strong> NSAIDs is stillmarkedly higher.40%30%20%10%0%Africa Asia Latin America“We are very aware that we do not provideadequate <strong>pain</strong> <strong>relief</strong> for our patients. We get ourdrugs from the local hospital <strong>and</strong> they only allowus basic <strong>pain</strong> analgesics. The hospital is notgood on drug procurement, <strong>and</strong> there are oftenshortages so they don’t give us what we order.”24

WORLD DAY REPORTGraph 14: Fac<strong>to</strong>rs decreasing access: supply <strong>and</strong> expense100%“Only small quantity used in a year compared<strong>to</strong> the fees required for importation.”% HCWs90%80%70%60%50%“Morphine is not available continuously. Smallamount imported <strong>and</strong> next order placed afterfinishing <strong>and</strong> reporting previous supply. Drugimporter does not inform the health centresabout the arrival of the next supply. Thus thereis a long period of drug absence becausewaiting for importing <strong>and</strong> informing.”40%30%20%10%0%Africa Asia Latin AmericaNot available from drug suppliers Unable <strong>to</strong> manufacture Too expensive“Nobody prepares morphine in the city. It isprepared 600km away <strong>and</strong> delivery takes twodays. Pharmaceuticals don’t want <strong>to</strong> producetheir own morphine… The lab preparationcosts US$80 per litre. I have spoken <strong>to</strong>pharmaceuticals <strong>and</strong> in three years I have hadno success.”“Small budget for health centres does not allowmorphine <strong>to</strong> be ordered in an adequatequantity. Thus only small quantities are ordered<strong>and</strong> imported.”25

3.4 ExpenseOral morphine is an inexpensive drug. Slow releasepreparations can be more expensive due <strong>to</strong> patents butare not required <strong>to</strong> provide good <strong>pain</strong> <strong>relief</strong>. Normalrelease preparations should be inexpensive <strong>to</strong> make;oral solution can often be made locally very cheaply.However, over one billion people live on less than $1 aday. (24) <strong>Palliative</strong> patients often lose their ability <strong>to</strong> earnor grow food so that even inexpensive drugs becomeimpossible <strong>to</strong> obtain. (25)Twenty-six per cent felt oral morphine was <strong>to</strong>oexpensive.Examples include:a. One main hospice in Zimbabwe can only accessnormal release oral morphine for half of the patientswho require it, as it is so expensive.b. In Honduras morphine (<strong>and</strong> all the other opioidanalgesics, eg oxycodone, hydromorphine, fentanyl)is available readily <strong>to</strong> private patients but, owing <strong>to</strong>expense, only rarely available <strong>to</strong> non-private patients.PromotionIn 2004, a survey found that the relative cost ofanalgesics in developing countries was significantlyhigher than in developed countries. Another paperreported how the high costs of opioids in Argentina(26, 27, 28)restricted their availability.of non-generic forms (ie patented versions ofthe drug) has caused morphine <strong>to</strong> be unaffordable insome areas. When expensive formulations of opioidsappear on the market, inexpensive immediate releasemorphine often becomes unavailable. Opioids are stillpoorly unders<strong>to</strong>od <strong>and</strong> underutilised in manydeveloping countries. Promotion of expensiveformulations disrupts the balance in their favour, asthere is seldom any promotion or education on thecheaper formulations. For example, in India even at themoment there are institutions which have onlysustained release morphine. There are others whichhave no morphine at all but have transdermal fentanyl,though the regula<strong>to</strong>ry barriers are the same for both. (29)26

WORLD DAY REPORT3.5 Lack of knowledge – HCWs,public <strong>and</strong> policy makers100%Graph 15: Fac<strong>to</strong>rs decreasing access: lack of knowledge90% Lack of knowledge on <strong>pain</strong>assessment, how <strong>to</strong> control80% <strong>pain</strong> <strong>and</strong>/or use <strong>and</strong>titration of oral morphine70%60%% HCWs50%Not on your country’s EssentialMedicines ListPoor access <strong>to</strong> health centresdue <strong>to</strong> preference fortraditional/local medicines or40% treatments“One of the main reasons in my state is thepaucity of doc<strong>to</strong>rs prescribing morphinebecause of the lack of training/interest inpalliative care.”“It is simply irrational that oral morphine is notavailable in the country whereas expensivefentanyl patches can be made available for therich patients. Lack of doc<strong>to</strong>rs training,awareness <strong>and</strong> cure orientated approach of thesociety as well as of the medical communitymakes palliative medicine an unknown field.”30%20%10%0%Africa Asia Latin America27

100%90%80%Graph 16: Fac<strong>to</strong>rs decreasing access: training70%Undergraduate trainingincluded treatment of <strong>pain</strong> &60%% HCWs use of opioids50%Undertaken/ing postgraduate course on treatment40% of <strong>pain</strong> & use of opioidsExclusion from a country’s essential drug list implieslack of underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the value of oral morphine in<strong>pain</strong> <strong>relief</strong> <strong>and</strong> possibly misunderst<strong>and</strong>ing of fears bypolicy makers.In Latin America <strong>and</strong> Asia less than 30% of the HCWssurveyed had <strong>pain</strong> management included in theirprofessional training. However, the majority, more than70%, of respondents had gone on <strong>to</strong> achieve furthertraining for themselves.As an undergraduate: 82% of HCWs in LatinAmerica <strong>and</strong> 71% of HCWs in Asia had notraining on <strong>pain</strong> or opioids.30%20%10%0%Africa Asia Latin America“There seems <strong>to</strong> be poor knowledge of palliativecare prescribing <strong>and</strong> fear at all levels of usingopioids even when they are available, includingamongst specialist doc<strong>to</strong>rs. For example, in my10 years experience… when we have suggestedusing, or asked about knowledge of using,combinations of, for example, haloperidol/hyoscine combos with or without opioids forterminal patients, it is negatively received.”28

WORLD DAY REPORT4. Essential elementsrequired <strong>to</strong> increaseavailabilitySimply providing a supply of any drug will not increaseaccess; a number of interlinked fac<strong>to</strong>rs need <strong>to</strong> beaddressed.4.1 EducationEducation is fundamental, ensuring that HCWsare aware of:how <strong>to</strong> diagnose <strong>pain</strong> <strong>and</strong> other symp<strong>to</strong>ms;which analgesics <strong>to</strong> use when, in what dose, howmany times a day, <strong>and</strong> for how long beforereassessment;how <strong>to</strong> prevent <strong>and</strong> minimise side effects;how <strong>to</strong> access advice <strong>and</strong> share knowledge;how <strong>to</strong> access local palliative care facilities;legal requirements <strong>and</strong> what, if any, records arenecessary;where necessary drugs can be sourced;dispelling ‘morphine myths’.It also empowers patients, carers, volunteers <strong>and</strong> eachcommunity through knowledge:that <strong>pain</strong> <strong>and</strong> other symp<strong>to</strong>ms can be relieved;of how <strong>to</strong> access palliative care facilities;of how <strong>to</strong> take drugs, minimise side effects, what <strong>to</strong>do if side effects occur (compliance is significantlyhigher when patients underst<strong>and</strong> reasons for theirmedicines, <strong>and</strong> knowledge of potential side effectsincreases trust).A survey in Ug<strong>and</strong>a illustrated how educatingcommunities can increase access <strong>and</strong> allayfears regarding morphine. (30)Finally, education is the key <strong>to</strong> ensuring that palliativecare is supported <strong>and</strong> legislation is not restrictive byeducating policy makers on:what palliative care is;the support INCB <strong>and</strong> international treaties give <strong>to</strong>ensuring opioids are available for medical purposes;how <strong>to</strong> account for movement of opioids <strong>and</strong>records required;the importance of integrating palliative care in<strong>to</strong>cancer <strong>and</strong> AIDS policies;how current laws can be improved <strong>to</strong> allow accesswhilst preventing diversion.Training is also vital for drug regula<strong>to</strong>ry personnel <strong>and</strong>police, <strong>to</strong> ensure knowledge of who can possess <strong>and</strong>h<strong>and</strong>le controlled drugs, <strong>and</strong> the records required.It is important also <strong>to</strong> ensure donors <strong>and</strong> NGOs areaware of a country’s priorities <strong>and</strong> requirements.29

4.2. Addressing the fearsA number of HCWs, government officials <strong>and</strong> patientsfear that having morphine available <strong>to</strong> relieve <strong>pain</strong> willlead <strong>to</strong> drug addiction (by HCWs, patients or throughdiversion <strong>to</strong> the general public).Dependence on a drug can be divided in<strong>to</strong>:Therapeutic dependence – analgesics do notremove the cause of the <strong>pain</strong>, therefore as long asthe <strong>pain</strong> remains (eg the tumour is still pressing on anerve) the patient will require the analgesic <strong>to</strong> remain<strong>pain</strong> free. Thus, patients may require morphine forthe rest of their life in order <strong>to</strong> remain <strong>pain</strong> free.Pharmacological dependence – the body producesits own <strong>pain</strong> relieving substances, endorphins, acertain level of which are circulating around the bodynormally. These are chemically similar <strong>to</strong> opioids.When a patient is given morphine regularly theirbody ‘senses’ an increase in ‘<strong>pain</strong> relieving’substances <strong>and</strong> responds by producing fewernatural endorphins. Consequently, if a patientsuddenly s<strong>to</strong>ps taking morphine, they will have alower level of endorphins than they had before theystarted taking morphine. This produces withdrawalsymp<strong>to</strong>ms. A similar reaction occurs with steroids.This can be simply avoided by slowly reducing thedose in patients that have been on morphine for afew weeks if the cause of the <strong>pain</strong> has resolved.Addiction (sometimes referred <strong>to</strong> as psychologicaldependence) – this is what is feared: abnormal,compulsive behaviour, including a desperation <strong>to</strong>obtain the drug in order <strong>to</strong> experience its psychiceffects, characteristically having continued usedespite harm.Studies show addiction or psychologicaldependence is extremely rare when opioids are(31, 32, 33)used for <strong>pain</strong>.Availability for medical use does not go h<strong>and</strong>-inh<strong>and</strong>with diversion for illegal purpose. (34)Twenty-one per cent of respondents felt that theircolleagues fear that patients will become <strong>to</strong>lerant <strong>to</strong>morphine, resulting in the need for higher <strong>and</strong> higherdoses <strong>to</strong> relieve their <strong>pain</strong> so that perhaps when <strong>pain</strong>becomes very severe morphine would no longer beeffective. This can cause HCWs <strong>to</strong> delay startingmorphine <strong>and</strong> other opioids, reserving them for‘exceptionally severe <strong>pain</strong>’.Once a patient is on the correct dose of opioid <strong>to</strong>relieve a <strong>pain</strong>, the dose will not need <strong>to</strong> be increased,unless the illness progresses, causing further <strong>pain</strong>, orthere is another source of <strong>pain</strong> or other fac<strong>to</strong>rs increasethe <strong>pain</strong> (social, spiritual, psychological). Then, whenthis <strong>pain</strong> is controlled, the dose will be kept stableagain. It is also important <strong>to</strong> explain <strong>to</strong> patients <strong>and</strong>relatives that:the <strong>pain</strong> may not become worse;not all <strong>pain</strong>s are 100% responsive <strong>to</strong> morphine, butthere are other types of analgesics which can betried.“Morphine should not be withheld until the <strong>pain</strong>becomes unbearable.”Note: a patient’s <strong>pain</strong> requirement may increase evenwhen there is no sign of disease progression.Pain is not only physical; psychological, spiritual <strong>and</strong>social fac<strong>to</strong>rs impact on <strong>pain</strong> intensity.Pain may not be solely due <strong>to</strong> the ‘main disease’.Disease progression may not be easy <strong>to</strong> detect.In addition, remember:There is also no maximum dose of morphine. Thedose should be increased <strong>to</strong> that required <strong>to</strong> relieve<strong>pain</strong>.Different <strong>pain</strong>s respond <strong>to</strong> different analgesics.Some <strong>pain</strong>s are only ‘partly’ responsive <strong>to</strong> opioids.Different opioids have different binding efficacies <strong>to</strong>different recep<strong>to</strong>rs, <strong>and</strong> therefore different analgesicproperties <strong>and</strong> side effects.Everybody has different <strong>pain</strong> thresholds, <strong>and</strong>express <strong>and</strong> cope with <strong>pain</strong> in different ways.“Only the patient knows how intense <strong>and</strong> frequenta <strong>pain</strong> is – a <strong>pain</strong> is what the patient says it is.”30

WORLD DAY REPORTDispelling the fear of <strong>to</strong>lerance:Ms CD, a 54 year old Argentinean nun, has had alocally advanced phaeochromocy<strong>to</strong>ma with lungmetastases since 1997. In November 1997 she wasreferred <strong>to</strong> the palliative care team <strong>and</strong> started with30mg a day of immediate release morphine. In August1998 the morphine was changed <strong>to</strong> 15mg a day ofmethadone. Until August 2006 her disease has beenstable, <strong>and</strong> her <strong>pain</strong> well controlled. She now receives10 mg a day of methadone.During eight years on methadone she has had a veryactive life in her religious community; she is able <strong>to</strong>travel <strong>and</strong> performs several daily activities.Case study provided by Dr Mariela Ber<strong>to</strong>lino, DrRober<strong>to</strong> Wenk <strong>and</strong> Dr Guillermo Mammana, from the<strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Unit , Tornu Hospital-FEMEBAFoundation.31

Thirty-eight per cent of respondents felt that fearside effects limited the use of oral morphine.All drugs have side effects. The side effects of morphine<strong>and</strong> other opioids are known <strong>and</strong> can be easilyminimised.Not all patients will experience side effectsThe following case study illustrates clearly how opioids donot render patients permanently drowsy, nor impaircognitive skills, nor are only used near the end of life –but how they can greatly enhance the life of the patient<strong>and</strong> their family.Ms EF had advanced nasopharyneal cancer. Shereceived oncology treatment <strong>and</strong> was referred <strong>to</strong> thepalliative care services in March 2003 with severe <strong>pain</strong>.The palliative care team started her on 12mg a day ofmethadone plus adjuvant analgesics. Her <strong>pain</strong> was wellcontrolled, allowing her <strong>to</strong> enjoy two more years ofactive life. Here she is pictured with her husb<strong>and</strong>,members of the palliative care team <strong>and</strong> two tangodancing teachers. She died at home in May 2005. Atthis time she was on 3mg of oral oxycodone PRN,(usually taken twice a day) plus adjuvants.One side effect which many fear is respira<strong>to</strong>rydepression – <strong>to</strong>lerance occurs <strong>to</strong> respira<strong>to</strong>ry depressionso that when the dose of morphine is increasedgradually, respira<strong>to</strong>ry depression does not occur. It is forthis reason that patients are started on smaller doses ofmorphine which are titrated up until the <strong>pain</strong> is relieved(not because the patient has become <strong>to</strong>lerant <strong>to</strong> the<strong>pain</strong> relieving properties). In addition, <strong>pain</strong> is arespira<strong>to</strong>ry stimulus, so the respira<strong>to</strong>ry depressive effectis ‘cancelled out’ when morphine is used <strong>to</strong> relieve <strong>pain</strong>.Other side effects such as sickness <strong>and</strong> drowsiness canalso be minimised by increasing the dose slowly.Tolerance <strong>to</strong> the constipating effect of morphine doesnot occur but can be anticipated <strong>and</strong> prevented usinglaxatives.Mr JK was a surgeon from Eastern Europediagnosed with disseminated cancer of theoesophagus. On diagnosis he was given somepalliative chemotherapy. Initially he experiencedsevere <strong>pain</strong> which limited him in his activities.Following referral <strong>to</strong> the palliative care team for<strong>pain</strong> control, his <strong>pain</strong> was controlled verysatisfac<strong>to</strong>rily with a 50 microgramme fentanylpatch <strong>and</strong> occasional immediate releasemorphine for breakthrough <strong>pain</strong>. Control of his<strong>pain</strong> allowed him <strong>to</strong> return <strong>to</strong> work, where hewas able <strong>to</strong> perform operations. Sadly hepassed away at the end of 2006, but until thenhe was very busy attending meetingsthroughout the country, giving short lectures aswell as enjoying weekends away with his family.Case study provided by Rober<strong>to</strong> Wenk, MD, MarielaBer<strong>to</strong>lino, MD, <strong>and</strong> María Minatel, MD.Programa Argentino de Medicina Paliativa-FundaciónFEMEBA, Buenos Aires, Argentina32

WORLD DAY REPORTHow side effects can be managed:Ms HI was a patient with ovarian carcinoma who wastreated for four years by the palliative care team, afterdiscontinuing chemotherapy. She had threeenterocutanea fistulas during these years <strong>and</strong> severeabdominal <strong>pain</strong> related with the progression of thedisease.Her <strong>pain</strong> was soon controlled with opioids.Unfortunately, she initially experienced someneuro<strong>to</strong>xicity, but the palliative care team managed thissuccessfully by rotation of class <strong>and</strong> doses of differen<strong>to</strong>pioids (morphine, oxycodone <strong>and</strong> methadone).Successful control of her <strong>pain</strong> <strong>and</strong> the side effectsmeant she was able <strong>to</strong> greatly enjoy many parts of thenext four years. She had an active life, she developedwork projects <strong>and</strong> most importantly was able <strong>to</strong> takecare of her two daughters. She was also able <strong>to</strong>undertake long-distance trips for some months <strong>to</strong> S<strong>pain</strong><strong>to</strong> see one of her sisters. Ms HI died in the palliative care unit in 2005, havingdeveloped brain metastases.Case study provided by Dr Mariela Ber<strong>to</strong>lino, Dr Rober<strong>to</strong> Wenk <strong>and</strong> Dr Guillermo Mammana, from the <strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Unit , Tornu Hopital-FEMEBAFoundation.33

4.3. AccountabilityOpioids are regulated under the 1961 UN Singleconvention on Narcotic Drugs (amended by the 1972<strong>and</strong> 1988 pro<strong>to</strong>cols). The purpose of the regulation is <strong>to</strong>guarantee their availability for medical purposes, whilstpreventing abuse. The INCB moni<strong>to</strong>r implementation ofthe conventions. The INCB requires each country <strong>to</strong>submit:an estimate of the quantity of each specified drug(including opioids) it will require for medical use –the amount imported or produced by a countryshould not exceed its agreed annual estimate;quarterly forms detailing the medical use of thespecified drugs (including opioids) within thecountry.Time, resources <strong>and</strong> definition of responsibilities needs<strong>to</strong> be made within the drug regula<strong>to</strong>ry authority forthese activities, <strong>and</strong> <strong>to</strong> ensure accountability throughoutthe h<strong>and</strong>ling of these drugs.Fac<strong>to</strong>rs limiting access <strong>to</strong> opioids include:fear by government officials <strong>and</strong>/or HCWs tha<strong>to</strong>pioid abuse will occur;fear by HCWs that they will be accused of abusingopioids if they h<strong>and</strong>le them.By keeping accurate records of the movement ofopioids <strong>and</strong> other restricted drugs, these worries canbe dispelled <strong>and</strong> the INCB requirements fulfilled. It isrecommended that records:are easy <strong>to</strong> complete;are kept throughout the whole supply chain(importation <strong>to</strong> patient supply or destruction orreturned);include details of:quantities acquired (imported/fromwholesaler/main hospital)supplier (eg wholesaler/doc<strong>to</strong>r)amount dispensed or suppliedwhom it was dispensed/supplied <strong>to</strong>separate running balance of the amount ins<strong>to</strong>ck for each form <strong>and</strong> strength kept (thisshould be verified with a regular physicalcount of the s<strong>to</strong>ck).Seventy-five per cent of HCWs responded that theykept some form of record of h<strong>and</strong>ling morphine in theirpractice. St<strong>and</strong>ardisation <strong>and</strong> provision of record booksfrom a central government level, the INCB or the WHOwould simplify this process.HCWs should advise drug authorities how significantchanges in palliative care services might alter thenational requirements for morphine <strong>and</strong> other stipulateddrugs. When estimating increases consider:the number of new patients likely <strong>to</strong> access theservice(s);the percentage of these likely <strong>to</strong> require morphine(or other drugs);the average dose of morphine any patient requiringmorphine is likely <strong>to</strong> require.34

WORLD DAY REPORT4.4.Reviewing laws <strong>and</strong> policiesPolicy change will only occur if governmentsunderst<strong>and</strong> the importance of palliative care <strong>and</strong> theneed <strong>to</strong> increase access <strong>to</strong> drugs for palliative carewithin their country. Thus, before changes <strong>to</strong> laws <strong>and</strong>policies can be addressed there is a need <strong>to</strong>:promote the benefit <strong>and</strong> role of palliative care,highlighting how many patients within the countrycould benefit;ensure all government individuals are aware of theability of inexpensive medicines <strong>to</strong> relieve <strong>pain</strong> in themajority of people, including children;document areas where the requirement for palliativecare is not met;develop leadership: workers within palliative carewho are willing <strong>to</strong> help affect change.National drug laws vary between countries. Drug lawsneed <strong>to</strong> be relevant <strong>and</strong> practical <strong>to</strong> clinical practice.For example, the drug laws were amended in Ug<strong>and</strong>arecently <strong>to</strong> allow specialist palliative nurses as well asdoc<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> prescribe oral morphine, as the number ofdoc<strong>to</strong>rs would not allow access <strong>to</strong> all patients requiring<strong>pain</strong> <strong>relief</strong>.There is a need <strong>to</strong> ensure palliative care is integratedin<strong>to</strong> national HIV/AIDS <strong>and</strong> cancer policies, countries’EMLs <strong>and</strong> treatment guidelines (<strong>and</strong> that all theseinclude children).A recent INCB meeting called for relevant countryauthorities <strong>to</strong> consider <strong>and</strong> modify any restrictions inplace which are not required by international law <strong>and</strong>which would potentially restrict access for medicalneed. (35)The PPSG has developed methods for evaluatingnational drug policies’ suitability <strong>to</strong> allow access <strong>to</strong>opioids for medical purposes whilst maintainingregulation, in cooperation with the WHO, palliative careexperts <strong>and</strong> government regula<strong>to</strong>rs. A <strong>to</strong>ol has beenpublished in conjunction with the WHO (2000) –Achieving balance in national opioids control policy:guidelines for assessment. (36) Details of this <strong>and</strong> furtherinformation on amending drug laws can be obtainedfrom www.<strong>pain</strong>policy.wisc.edu“…consensus among all governments that themedical use of narcotic drugs continues <strong>to</strong> beindispensable for the <strong>relief</strong> of <strong>pain</strong> <strong>and</strong> suffering<strong>and</strong> that adequate provision must be made <strong>to</strong>ensure the availability of narcotic drugs forsuch purposes.” (37) 35

4.5 Strengthening health facilities4.5.1 Human resourcesStrengthening of many countries’ health services isrequired <strong>to</strong> enable full access <strong>to</strong> palliative <strong>and</strong> otherdrugs. It is likely that different structures <strong>and</strong>approaches will work better in different countries.It is recommended when establishing or exp<strong>and</strong>ingservices <strong>to</strong>:examine existing services, their effectiveness <strong>and</strong>disadvantages;ensure integration with existing models;encourage community participation;ensure cooperation with the private sec<strong>to</strong>r;communicate clearly <strong>to</strong> donors what is required.Lack of trained HCWs contributes <strong>to</strong> inaccess <strong>to</strong>palliative drugs in a number of countries. The number<strong>and</strong> skill mix of HCWs varies widely between countries.Ways in which <strong>to</strong> address this problem will also vary,perhaps, for example, utilising <strong>and</strong> paying laycounsellors, ensuring quality training <strong>and</strong> support ofvolunteers, <strong>and</strong> establishing guidelines nurses canfollow, with a referral doc<strong>to</strong>r available.4.5.2 Drug procurementEnsuring a reliable, timely, quality <strong>and</strong> inexpensive drugsupply is important <strong>to</strong> ensure patients remain <strong>pain</strong> free<strong>and</strong> prevent withdrawal reactions. Accounting for opioiduse will help estimate quantities required. There are anumber of steps in the drug procurement process:Planning – ensuring sufficient supplies are alwaysavailable but that s<strong>to</strong>ck does not expire, ascertainingwhat is the best form <strong>to</strong> use, finding a reliableimporter or supplier, co-ordination with otherorganisations (it is often more cost effective <strong>to</strong> havea central source therefore collaboration is important).Importation – sufficient time needs <strong>to</strong> be given <strong>to</strong>allow for form filling <strong>and</strong> potential delays, <strong>and</strong> goodcommunication between clinicans <strong>and</strong> procurement‘agents’ is vital.Manufacture – is it cheaper <strong>to</strong> manufacture locally orin-house; who nearby has the capacity? Is the finalformulation cheaper <strong>to</strong> import? For small scalemanufacture (production of drugs from raw materialsin your health facility) you will require:reliable source of raw materials;good water supply;accurate weighing scales <strong>and</strong> measures;funnels, bowls, pestle <strong>and</strong> mortar;labels;containers for final product;verified formula;trained staff;appropriate s<strong>to</strong>rage for raw materials <strong>and</strong>final product;quality control procedures in place.Transportation – who is allowed <strong>to</strong> collect controlleddrugs from a wholesaler?36

WORLD DAY REPORT4.5.3 Drug costsEstablishing a reliable, quality assured <strong>and</strong> inexpensivedrug supply <strong>and</strong> distribution is not always easy.Many pharmaceutical companies are not interested inmanufacturing morphine or in obtaining a licence fortheir formulation in countries where usage is thought <strong>to</strong>be low <strong>and</strong> bureaucracy potentially cumbersome.Perhaps there should be a call <strong>to</strong> the WHO <strong>to</strong> establishreliable <strong>and</strong> inexpensive manufacturing of drugs on theWHO EML?Morphine solution can be made cheaply from thepowdered form. However, many smaller providers lackthe scales, raw materials <strong>and</strong> qualified staff; only 32%of the respondents worked in units which had facilitiesfor making morphine solution from the powder <strong>and</strong> thens<strong>to</strong>ring it in a secure place. Hence, establishing incountrycentral production <strong>and</strong> adequate distributioncan be a good option. In some places a larger hospitalor NGO organisation has agreed <strong>to</strong> manufacturemorphine solution as a central supplier.For example:In Ug<strong>and</strong>a in 2000 following advocacy by <strong>Hospice</strong>Ug<strong>and</strong>a, the MoH commissioned a charitableprocurement <strong>and</strong> manufacturing facility <strong>to</strong> producemorphine solution which could be distributed <strong>to</strong>hospitals, health centres <strong>and</strong> palliative careproviders as requested. Commercial manufacturershad been approached but owing <strong>to</strong> the lack of profitthey were not interested in manufacturing morphinesolution.In Nigeria supply of morphine through centralimportation had been erratic since 1993. Followingadvocacy by the Society for the Study of Pain <strong>and</strong>the Centre for <strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong>, the University CollegeHospital pharmacy in Ibadan now prepares oralmorphine from the morphine powder (5mg/5ml <strong>and</strong>50mg/5ml) <strong>and</strong> supplies patients across the country(with over 130 prescriptions per month beingdispensed for cancer patients from all over thecountry).37

5. Recent advances inincreasing access <strong>to</strong>analgesicsOver the last 10 years access <strong>to</strong> analgesics hasincreased substantially in a number of countries orregions within a country. A few of these are outlinedbelow (this is not a comprehensive list).5.1 IndividualsNumerous individuals have made significant stepsin increasing patient access <strong>to</strong> analgesics in the last10 years.“I am instruc<strong>to</strong>r at the residence of generalmedicine in the hospital where I work, <strong>and</strong> I trainresidents annually in the formation of generalpalliative care, especially in the treatment of <strong>pain</strong><strong>and</strong> opioid use. This has generated somechanges for the better. Furthermore, I produced abasic guide that deals with the process of <strong>pain</strong>treatment <strong>and</strong> use of opioids, which is starting <strong>to</strong>be used by doc<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>and</strong> nurse interns, <strong>and</strong>hospital guards. We are currently creating apalliative care team.”5.2 WHO <strong>and</strong> INCBIn 2005 the <strong>World</strong> Health Assembly (WHA) <strong>and</strong>ECOSOC adopted resolutions inviting the INCB <strong>and</strong> theWHO <strong>to</strong> examine the feasibility of assisting in projects<strong>to</strong> increase the availability of opioid analgesics(resolutions ECOSOC 2005/25 <strong>and</strong> WHA58.22). TheINCB <strong>and</strong> the WHO agreed that the WHO would act asthe focal point, with the WHO preparing the ‘<strong>Access</strong> <strong>to</strong>Controlled Medications Programme’. The programme,which will commence in late 2007 or 2008, aims <strong>to</strong> workwith all involved, including governments <strong>and</strong> NGOs,addressing the situation in over 150 countries with bador no access.The PPSG has published 22 translations of the WHOpublication Achieving balance (36) which provides aresource for governments <strong>and</strong> HCWs <strong>to</strong> evaluate <strong>and</strong>improve national laws on preventing access <strong>to</strong> opioids.www.<strong>pain</strong>policy.wisc.edu5.3 Resolutions advocating for anincrease in accessibility <strong>to</strong> opioidanalgesicsECOSOC 2005/25 – On treatment of <strong>pain</strong> usingopioid analgesics.WHA 55.22 (25-05-2005) on Cancer prevention <strong>and</strong>control“...<strong>to</strong> examine jointly with the International NarcoticsControl Board the feasibility of a possible assistancemechanism that would facilitate the adequatetreatment of <strong>pain</strong> using opioid analgesics”.38

WORLD DAY REPORT5.4Changes in national laws1. In February 2002 the PPSG, the Eastern Europeanregional office of the WHO <strong>and</strong> the Open SocietyInstitute (OIS) conducted a workshop on ‘Assuringthe Availability of Opioid Analgesics for <strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong>within Eastern Europe’. From this, Bulgaria, Croatia,Hungary, Lithuania, Pol<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Romania completedaction plans <strong>to</strong> help address regulations whichimpeded access. Romania was chosen as a pilotcountry.2.<strong>Hospice</strong> Casa Sperantei in Romania wascommissioned by the Romanian MoH <strong>to</strong> review theiropioid legislation <strong>and</strong> policy using the WHOguidelines. Recommendations were presented <strong>to</strong> theMoH in 2003 which would help increase access <strong>to</strong>opioids for patients, eg increasing the supply ofopioids allowed <strong>to</strong> be given <strong>to</strong> patients from threedays <strong>to</strong> 30 days. The recommendations wereaccepted <strong>and</strong> the new law, nr 339/Nov 2005, hasbeen in action since July 2006, although it needs <strong>to</strong>be printed in the official journal before the regulation(20, 38)can be applied.In Kerala, India, advocacy <strong>and</strong> amendment of statedrug regulations laws now allows more than 100palliative care units around the state <strong>to</strong> have access<strong>to</strong> oral morphine. An audit demonstrated thatincreased use of oral morphine did not lead <strong>to</strong>diversion <strong>and</strong> misuse. (34)3.The Ug<strong>and</strong>an Government has recently amendeddrug laws <strong>to</strong> allow clinical officers <strong>and</strong> nurses whohave completed a specialised course in palliative care<strong>to</strong> be able <strong>to</strong> prescribe oral morphine. (39) This followsthe recognition of the shortage of doc<strong>to</strong>rs within thecountry. Zimbabwe also allows specifically trainednurses <strong>to</strong> prescribe oral morphine <strong>and</strong> theDemocratic Alliance Government in South Africa hasrecently proposed that prescribing by speciallytrained nurses should be allowed in South Africa<strong>to</strong>o. (17)4.The PPSG has documented recent changes in lawsaimed at improving access <strong>to</strong> morphine; theseinclude increasing the length of supply which can beprescribed <strong>and</strong> dispensed:1. France: 1995Seven days increased <strong>to</strong> 28 days2. Mexico:Five days increased <strong>to</strong> 30 days3. Italy: 2001Eight days increased <strong>to</strong> one month;in addition simplified prescription format <strong>and</strong>allowed two drugs or dosage units on one form4. Germany:One day increased so there is no limit5. Peru:One day increased <strong>to</strong> 14 days6. India:Five licenses required decreased <strong>to</strong> two licensesfor morphine9. Romania:Three days supply increased <strong>to</strong> 30 days supply10. Colombia:10 days increased <strong>to</strong> 30 days (for strong opioids)39

5.5 Some regional initiatives401. Pallium India (Trust), working with the PPSG <strong>and</strong> theNational Cancer Institute (USA), has facilitated thecreation of palliative care facilities in three cancercentres in three states, in which effective palliative carefacilities did not previously exist. Working with theAmerican Cancer Society <strong>and</strong> International Network forCancer Treatment <strong>and</strong> Research, the trust has alsocatalysed the development of a palliative care trainingcentre in Hyderabad.2. <strong>Hospice</strong> Africa (Ug<strong>and</strong>a) has been running aprogramme <strong>to</strong> help train HCWs in other Africancountries <strong>and</strong> help approach government officials <strong>and</strong>advocate the need for palliative care <strong>and</strong> morphine. Todate, visits/courses for African countries have beenheld in Ethiopia, Tanzania, Malawi, Nigeria, Kenya,Ghana, Zambia, <strong>and</strong> for South Africa in Kampala <strong>and</strong>Ug<strong>and</strong>a. Funding has come from the RAF (UK) grant<strong>and</strong> the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund.3. The African <strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Association (APAC)provides advice on the provision of affordable, culturallyappropriate palliative care throughout Africa. Initial visits<strong>to</strong> Sierra Leone (2005) have led <strong>to</strong> advice <strong>to</strong> smallinitiatives as well as discussion with Ministry officials as<strong>to</strong> the importance of palliative care. APCA is currentlyworking in collaboration with the PPSG <strong>to</strong> help anumber of African countries examine their drug laws, <strong>to</strong>ensure they allow access. In 2006 a workshop wascommissioned <strong>to</strong> help establish country plans <strong>and</strong>examine drug regulations.info@apac.co.ug; www.apac.co.ug4. Help the <strong>Hospice</strong>s runs a Twinning programme for<strong>Hospice</strong>s – a two-way sharing of ideas <strong>and</strong>experiences. Seewww.hospiceinformation.info/hospicesworldwide/twinning.asp5.6 Some country initiatives1. IndiaIn 2005 the government of India appointed a task forceof experts <strong>to</strong> assist it in formulating a strategy for thecountry’s National Cancer Control Programme, a fiveyear plan which is due <strong>to</strong> commence in 2007. The taskforce consisted of separate groups each for anindividual area in cancer control <strong>and</strong> care. One of thesegroups was on ‘<strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>and</strong> Rehabilitation’. Thegroup had extensive discussions via email <strong>and</strong> met acouple of times. Its recommendations, which weresubmitted <strong>to</strong> the government in May 2006, includedstrategy for:the creation of palliative care facilities, or upgradingthem where they existed, in all of 28 RegionalCancer Centres in the country;the upgrade of five centres <strong>to</strong> training centres;the creation of 100 other palliative care facilities inother oncology centres so that each state wouldhave at least two palliative care services;the inclusion of palliative care in undergraduatemedical <strong>and</strong> nursing curriculum, <strong>and</strong> in thepostgraduate curriculum for oncology trainees;the simplification of narcotic regulations in all states in India (currently 15 of 28 states havecomplicated rules);community participation in palliative care delivery.2. Romania<strong>Hospice</strong> Casa Sperantei in Romania:has prepared a training curriculum (20 hours) <strong>and</strong>has educated 40 trainers <strong>to</strong> run a national trainingprogramme in the use <strong>and</strong> prescribing of opioids.This was funded by Help the <strong>Hospice</strong>s <strong>and</strong> theOpen Society Institute, New York;under the umbrella of the national postgraduatetraining centre, is running courses for doc<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>and</strong>pharmacists detailing the use <strong>and</strong> prescribing ofopioid medication in 30 districts of Romania, in order<strong>to</strong> facilitate the implementation of the new opioidlegislation. This is funded by the Open SocietyInstitute New York <strong>and</strong> three drug companies:Janssen, Lannacher <strong>and</strong> Mundipharma.cshospice@hospice.bv.astral.ro

WORLD DAY REPORT3. NigeriaProfessor Olaitan Soyannwo <strong>and</strong> four colleagues fromIbadan began advocating for opioid availability in 1996.Their dedication <strong>and</strong> enthusiasm over the last 10 yearshas led <strong>to</strong>:the establishment of the Society for the Study ofPain, Nigeria (a chapter of the InternationalAssociation for the Study of Pain);the creation of the Centre for <strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong>, Nigeria.Their inspiration has led <strong>to</strong> individual <strong>and</strong> groupinitiatives including:a home based palliative care service (supported by<strong>Hospice</strong> Africa, UK);training workshops; setting up a <strong>pain</strong>/palliative care clinic; the development of the National <strong>Palliative</strong> <strong>Care</strong>Guidelines adopted in 2006 by the Federal Ministryof Health (including the use of the WHO analgesicladder <strong>and</strong> opioids for severe <strong>pain</strong>);the inauguration of a consultative committee forcancer care (including a sub-committee on palliativecare) in<strong>to</strong> the Nigerian MoH in Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2006.Formation of this committee has allowed ProfessorSoyannwo <strong>to</strong> guide other committee members abouthow their hospitals can access opioids; prior accesswas denied in many hospitals owing <strong>to</strong> a lack ofknowledge about how <strong>to</strong> access opioids;symposia for healthcare practitioners;inclusion of palliative care <strong>and</strong> safe use ofanalgesics in undergraduate <strong>and</strong> postgraduateteaching, <strong>and</strong> input in<strong>to</strong> curriculum review;the dissemination of information about opioidaccessibility <strong>and</strong> safe use through the NigerianSociety of Anaesthetists, the West African college ofSurgeons annual conferences, <strong>and</strong> in-servicetraining units of hospitals, eg resident doc<strong>to</strong>rs,nursing, HIV <strong>and</strong> cancer centers.4. Ug<strong>and</strong>aDr Anne Merriman <strong>and</strong> dedicated colleagues set up ahospice in Kampala in 1993 after ensuring thegovernment would allow oral morphine <strong>to</strong> be used for<strong>pain</strong> <strong>relief</strong>. <strong>Hospice</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>a has exp<strong>and</strong>ed <strong>and</strong> nowincludes three centres in Ug<strong>and</strong>a, as well as serving asa model <strong>Hospice</strong> for Africa <strong>and</strong> aiding other Africancountries in establishing palliative care facilities.Projects <strong>and</strong> initiatives include:three centres providing home care service forapproximately 900 patients at one time;certified in-country training for healthcareprofessionals in palliative care, currently workingclosely with MoH <strong>to</strong> ensure training in all districts;providing special training for clinical officers <strong>and</strong>nurses <strong>to</strong> lead palliative care units in their hospitalsor teams. These nurses <strong>and</strong> clinical officers areallowed <strong>to</strong> prescribe morphine following a recentchange in Ug<strong>and</strong>an law;certified in-country training for volunteers in palliativecare;training of trainers courses;advocacy leading <strong>to</strong>:the inclusion of palliative care as an essentialcomponent in the MoH five year strategicplan in 2000 – this in turn led <strong>to</strong> increasedaccess <strong>to</strong> oral morphine <strong>and</strong> amendments <strong>to</strong>Ug<strong>and</strong>an laws <strong>to</strong> allow specially trainedclinical officers <strong>and</strong> nurses <strong>to</strong> prescribe oralmorphine;the inclusion of palliative care training inprofessional undergraduate courses.41

5.7 Proposed projectsPPSG, a WHO collaborating centre:Internet courses on international <strong>pain</strong> policy.International Pain Policy Fellowship.New opioid statistics <strong>to</strong> allow the study ofconsumption (use) for medical purposes <strong>and</strong>estimated requirement:<strong>to</strong> aggregate opioids for severe <strong>pain</strong> in<strong>to</strong>one number (ie combine figures for use oforal methadone, oral morphine, oraloxycodone etc);<strong>to</strong> estimate minimum country needs basedon mortality.Guidance as <strong>to</strong> the essential elements of abalanced national drug law.Opioid availability profile for every country.Provision of support by international experts:speaker supportdatacollaboration.6. Educationalopportunities1. <strong>Hospice</strong> Ug<strong>and</strong>a – postgraduate multidisciplinarydiploma in palliative care2. Pallium Latinoamerica – distance learning advancedcourse in palliative care (multidisciplinary,postgraduate course in Spanish) www.pallium.org3. Wisconsin fellowship4. Programa Argentino de Medicina Paliativa-FundaciónFEMEBA, Buenos Aires, Argentina – one hundred<strong>and</strong> sixty hours face <strong>to</strong> face (70% clinical practice inpalliative care units) postgraduate courses inpalliative care for physicians, nurses <strong>and</strong>psychologists. E-courses for physicians <strong>and</strong>nurses. (40) Both activities are in Spanish(paliativo_femeba@arnet.com.ar)5. The IAHPC website details a number of otherdiplomas <strong>and</strong> courses in palliative care www.hospicecare.com/edu7.What you can do7.1 AdvocacyGovernmentsHCWsPublicCall for provision of reliable <strong>and</strong> inexpensive sourceof EML drugs7.2 EducationSupport initiatives7.3 Support for hospices throughinternational organisations <strong>and</strong>directlyVolunteeringFinancialCoordination of services7.4ResearchHow <strong>to</strong> increase access, demonstrating diversion isnot a problem.42