European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer ...

European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer ... European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer ...

Rug / Back European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis F i r s t E d i t i o n European Commission

- Page 2 and 3: European Commission European Guidel

- Page 4 and 5: Cover Upper left: surgically excise

- Page 6 and 7: Financial support of the European C

- Page 8 and 9: Address for correspondence Quality

- Page 10 and 11: AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND

- Page 12 and 13: AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND

- Page 14 and 15: AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND

- Page 16 and 17: AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND

- Page 19 and 20: PREFACE Preface John Dalli* Colorec

- Page 21 and 22: PREFACE Finally, as Director of an

- Page 23 and 24: PREFACE Preface J Patnick, N Segnan

- Page 25: Table of contents

- Page 28 and 29: TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.3.2.2 Evidence

- Page 30 and 31: TABLE OF CONTENTS 3.2.5 Data tables

- Page 32 and 33: TABLE OF CONTENTS 5.5 After the pro

- Page 34 and 35: TABLE OF CONTENTS 7.6.4 Sectioning

- Page 36 and 37: TABLE OF CONTENTS 9.2.3 Patient cha

- Page 38 and 39: TABLE OF CONTENTS Append ices i App

- Page 40 and 41: Authors Lawrence von Karsa, IARC Ju

- Page 42 and 43: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Screening is perf

- Page 44 and 45: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Guideline publica

- Page 46 and 47: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY the design of the

- Page 48 and 49: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY capacity (Cotton

- Page 50 and 51: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Summary Table of

Rug / Back<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis F i r s t E d i t i o n<br />

<strong>European</strong> Commission

<strong>European</strong> Commission<br />

<strong>European</strong> Guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>for</strong> Quality Assurance <strong>in</strong> Colorectal Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

Diagnosis - First Edition<br />

Segnan N, Patnick J, von Karsa L (eds), 2010<br />

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the <strong>European</strong> Union<br />

ISBN 978-92-79-16435-4 (pr<strong>in</strong>ted version)<br />

ISBN 978-92-79-16574-0 (CD-version)<br />

14 November 2011<br />

ERRATA Version 1.<br />

The follow<strong>in</strong>g errata apply to the first version of the Guidel<strong>in</strong>es that was made available on the<br />

website of the <strong>European</strong> Union <strong>in</strong> February 2011. They have been corrected <strong>in</strong> the second version of<br />

the Guidel<strong>in</strong>es.<br />

p. VI Replace: Henn<strong>in</strong>g Erfkampf<br />

by: Henn<strong>in</strong>g Erfkamp<br />

pp. VII, 145 & 146 Replace: Ernst Kuipers<br />

By: Ernst J. Kuipers<br />

p. XLVI, po<strong>in</strong>t 7 Delete: after positive FS<br />

p.114, para. 7 Replace: PK isoenzyme type M2 has shown poor sensitivity and specificity<br />

when used alongside two immunochemical devices (Mulder et al 2007).<br />

By: When used alongside guaiac-based or immunochemical devices, PK<br />

isoenzyme type M2 has not shown adequate specificity <strong>for</strong> population<br />

screen<strong>in</strong>g (Shastri et al. 2006; Mösle<strong>in</strong> et al 2010).<br />

p. 141 Insert: Mösle<strong>in</strong> G, Schneider C, Theilmeier A, Erckenbrecht H, Normann S,<br />

Hoffmann B, Tilmann-Schmidt D, Horstmann O, Graeven U & Poremba C<br />

(2010), [Analysis of the statistical value of various commercially available<br />

stool tests - a comparison of one stool sample <strong>in</strong> correlation to colonoscopy],<br />

Dtsch.Med Wochenschr., vol. 135, no. 12, pp. 557-562.<br />

p. 142, para. 3 Delete: Mulder SA, van Leerdam ME, van Vuuren AJ, Francke J, van<br />

Toorenenbergen AW, Kuipers EJ & Ouwendijk RJ (2007), Tumor pyruvate<br />

k<strong>in</strong>ase isoenzyme type M2 and immunochemical fecal occult blood test:<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance <strong>in</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>, Eur.J.Gastroenterol.Hepatol.<br />

vol. 19, no. 10, pp. 878-882.<br />

p. 143 Insert: Shastri YM, Naumann M, Oremek GM, Hanisch E, Rosch W, Mossner J,<br />

Caspary WF & Ste<strong>in</strong> JM (2006), Prospective multicenter evaluation of fecal<br />

tumor pyruvate k<strong>in</strong>ase type M2 (M2-PK) as a screen<strong>in</strong>g biomarker <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>colorectal</strong> neoplasia, Int J Cancer, vol. 119, no. 11, pp. 2651-2656.

<strong>European</strong> Commission<br />

<strong>European</strong> Guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>for</strong> Quality Assurance <strong>in</strong> Colorectal Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

Diagnosis - First Edition<br />

Segnan N, Patnick J, von Karsa L (eds), 2010<br />

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the <strong>European</strong> Union<br />

ISBN 978-92-79-16435-4 (pr<strong>in</strong>ted version)<br />

ISBN 978-92-79-16574-0 (CD-version)<br />

27 July 2012<br />

Addendum<br />

For a journal publication, the authors, contributors, editors and reviewers were requested to review<br />

their declarations of <strong>in</strong>terest based on the new IARC procedures adopted s<strong>in</strong>ce publication of the<br />

orig<strong>in</strong>al Guidel<strong>in</strong>es book. The follow<strong>in</strong>g revised declarations were received:<br />

Dr Hermann Brenner is employed by The German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) that has received<br />

significant research support from Eiken Chemicals (less than 40 000 €) <strong>for</strong> previously and currently<br />

runn<strong>in</strong>g studies on <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> detection. The follow<strong>in</strong>g companies have provided the DKFZ with<br />

faecal occult blood tests free of charge <strong>for</strong> previously and currently runn<strong>in</strong>g evaluation studies: ulti<br />

med, Ahrensburg, Germany; DIMA, Gott<strong>in</strong>gen, Germany; Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany;<br />

CAREdiagnostica, Voerde, Germany; Preventis, Bensheim, Germany; Quidel, San Diego, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia.<br />

The total value of the non-monetary support is less than 100 000 €.<br />

Dr Christian Pox has received lecture honoraria and travel support of less than 7 000 € from the<br />

follow<strong>in</strong>g manufacturers of pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, medical equipment and other health<br />

products: Dr Falk Pharma, Hitachi and Roche. He has also received consultancy fees of 1 500 € <strong>for</strong><br />

attend<strong>in</strong>g an Advisory Board Meet<strong>in</strong>g of the Abbot company, a broad-based health care manufacturer,<br />

and 2 100 € from the AQUA Institute, Germany, a private entity dedicated to <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong><br />

research and implementation that is mandated by the Federal Committee of the German Statutory<br />

Health Insurance System to implement a nationwide <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> scheme.<br />

Dr Wolff Schmiegel is the holder of one patent and the co-holder of three patents cover<strong>in</strong>g<br />

technologies related to screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis of <strong>colorectal</strong> tumours. He is also co-holder of a patent<br />

cover<strong>in</strong>g substances potentially suitable <strong>for</strong> prevention and treatment of <strong>colorectal</strong> polyps. He has<br />

received consultancy fees of less than 2 000 € from Astra Zeneca and consultancy fees, lecture<br />

honoraria and travel support totall<strong>in</strong>g less than 16 000 € from Roche. He has also received lecture<br />

honoraria from Abbott, Pfizer and Falk. The Medical Faculty of the Ruhr University <strong>in</strong> Germany where<br />

he works has received <strong>in</strong>stitutional research fund<strong>in</strong>g of less than 165 000 € from Roche and the<br />

pharmaceutical manufacturer Sanofi Aventis <strong>for</strong> studies <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis.<br />

Dr Schmiegel is the sole shareholder (25 000 €) of Medmotive GmbH, a hold<strong>in</strong>g that until 2010<br />

controlled 25% of the company Westdeutsches Darm-Centrum GmbH with a capital <strong>in</strong>vestment of<br />

25 000 €. The aim of these companies is to develop and coord<strong>in</strong>ate a <strong>quality</strong>-assured network <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>colorectal</strong> oncology through such activities as consult<strong>in</strong>g, development of therapeutic standards,<br />

specialized tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and lobby<strong>in</strong>g key stakeholders.<br />

Dr Graeme Young has received consultancy fees (less than 10 000 €) from Quidel Corporation, a<br />

manufacturer of diagnostic products. Eiken Chemicals has provided Fl<strong>in</strong>ders University where he works<br />

with faecal occult blood tests free of charge <strong>for</strong> studies (total value less than 10 000 €).

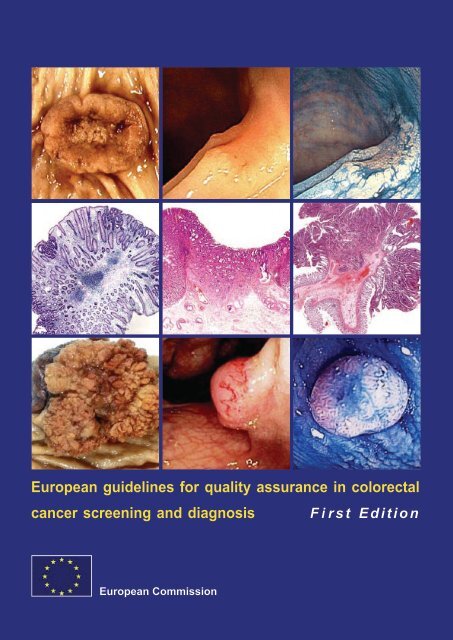

Cover<br />

Upper left: surgically excised pT2 adenocarc<strong>in</strong>oma of the rectum<br />

Upper middle: depressed carc<strong>in</strong>oma (0-IIc), 7mm, submucosal <strong>in</strong>vasion<br />

Upper right: same lesion, chromoscopy with <strong>in</strong>digocarm<strong>in</strong>e solution<br />

Centre left: tubular adenoma at <strong>in</strong>itial stage, 12 mm, HE sta<strong>in</strong><br />

Centre middle: depressed carc<strong>in</strong>oma (0-IIa+IIc), 10 mm, massive submucosal <strong>in</strong>vasion, HE sta<strong>in</strong><br />

Centre right: tubulovillous adenoma giv<strong>in</strong>g rise to a pY1 adenocarc<strong>in</strong>oma <strong>in</strong>vad<strong>in</strong>g the polyp stalk and<br />

show<strong>in</strong>g vascular <strong>in</strong>vasion. Completely excised<br />

Lower left: Large colonic tubulovillous adenoma, surgically excised due to size<br />

Lower middle: sessile adenocarc<strong>in</strong>oma (0-Is), 13 mm, superficial distorted vessels, submucosal <strong>in</strong>vasion<br />

Lower right: sessile adenoma (0-Is), 8 mm, chromoscopy with <strong>in</strong>docarm<strong>in</strong>e solution<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Upper left, centre right and lower left: Images supplied by Professor P. Quirke, Leeds, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom.<br />

Upper middle and right: images provided by Dr S. Tanaka, Hiroshima, Japan.<br />

Centre left: image provided by Dr M. Vieth, Bayreuth, Germany.<br />

Centre middle: image provided by Dr H. Watanabe, Niigata, Japan.<br />

Lower middle and right: images provided by Dr A. Chavaillon, Lyon-Bourgo<strong>in</strong>, France.

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis First Edition<br />

Editors<br />

N. Segnan<br />

J. Patnick<br />

L. von Karsa

F<strong>in</strong>ancial support of the <strong>European</strong> Communities through the EU Public Health Programme (Development<br />

of <strong>European</strong> Guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>for</strong> Quality Assurance of Colorectal Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g (CRC), grant agreement<br />

No. 2005317), of the Public Affairs Committee of the United <strong>European</strong> Gastroenterology Federation,<br />

and from a cooperative agreement between the American Cancer Society and the Division of<br />

Cancer Prevention and Control at the Centers <strong>for</strong> Disease Control and Prevention is gratefully acknowledged.<br />

The views expressed <strong>in</strong> this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official<br />

position of the <strong>European</strong> Commission.<br />

Neither the Commission nor any person act<strong>in</strong>g on its behalf can be held responsible <strong>for</strong> any use that<br />

may be made of the <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation <strong>in</strong> this document.<br />

Special thanks are due to the IARC staff <strong>in</strong> the Communications, Quality Assurance and Screen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Groups who provided technical assistance.<br />

Europe Direct is a service to help you f<strong>in</strong>d answers to<br />

your questions about the <strong>European</strong> Union.<br />

Freephone Number (*):<br />

00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11<br />

(*) Certa<strong>in</strong> mobile telephone operators do not allow access to<br />

00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed.<br />

Further <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation on the EU Health Programme is available at:<br />

http://ec.europa.eu/health/<strong>in</strong>dex_en.htm<br />

Catalogu<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation can be found at the end of this publication.<br />

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the <strong>European</strong> Union, 2010<br />

ISBN 978-92-79-16435-4 (Pr<strong>in</strong>ted version)<br />

ISBN 978-92-79-16574-0 (Electronic version)<br />

doi:10.2772/1458 (Pr<strong>in</strong>ted version)<br />

doi:10.2772/15379 (Electronic version)<br />

© <strong>European</strong> Union, 2010<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> Belgium<br />

PRINTED<br />

ON WHITE CHLORINE-FREE PAPER<br />

II <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

EDITORS<br />

Joan Austoker (1947 – 2010)<br />

This edition is dedicated to the memory of our colleague and friend Joan Austoker who<br />

contributed substantially to the development of the <strong>European</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong><br />

through her pioneer<strong>in</strong>g work <strong>in</strong> communication <strong>in</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and prevention.<br />

Nereo Segnan<br />

Unit of Cancer Epidemiology, Department of Oncology<br />

CPO Piemonte (Piedmont Centre <strong>for</strong> Cancer Prevention) and S. Giovanni University Hospital<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

Julietta Patnick<br />

NHS Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g Programmes<br />

Sheffield, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

and<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d University Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g Research Unit<br />

Cancer Epidemiology Unit<br />

University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Lawrence von Karsa<br />

Quality Assurance Group<br />

Section of Early Detection and Prevention<br />

International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition III

Address <strong>for</strong> correspondence<br />

Quality Assurance Group<br />

Section of Early Detection and Prevention<br />

International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

150 cours Albert Thomas<br />

F-69372 Lyon cedex 08, France<br />

IV <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND REVIEWERS<br />

Authors, Contributors, Editors and ReviewersF<br />

Lars Aabakken, Rikshospitalet University Hospital<br />

Oslo, Norway<br />

Lutz Altenhofen, Central Research Institute of Ambulatory Health Care<br />

Berl<strong>in</strong>, Germany<br />

Rosemary Ancelle-Park, Direction Générale de la Santé<br />

Paris, France<br />

Nataša Antoljak, Croatian National Institute of Public Health<br />

Zagreb, Croatia<br />

Paola Armaroli 2 , CPO Piemonte<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

Silv<strong>in</strong>a Arrossi, Centro de Estudios de Estado y Sociedad - CEDES/Consejo Nacional de<br />

Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas - CONICET, Buenos Aires Argent<strong>in</strong>a<br />

Wendy Atk<strong>in</strong>, Imperial College London<br />

Harrow, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Joan Austoker † , University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Johannes Blom, Karol<strong>in</strong>ska Institutet<br />

Stockholm, Sweden<br />

Hermann Brenner, German Cancer Research Centre<br />

Heidelberg, Germany<br />

Michael Bretthauer , Rikshospitalet University Hospital<br />

Oslo, Norway<br />

Guido Costamagna, A. Gemelli University Hospital,<br />

Rome, Italy<br />

Jack Cuzick, Cancer Research UK<br />

London, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

1<br />

Authors, contributors, editors and reviewers serve <strong>in</strong> their <strong>in</strong>dividual capacities as experts and not as representatives<br />

of their government or any other organisation with which they are affiliated. Affiliations are provided <strong>for</strong><br />

identification purposes only.<br />

M<strong>in</strong>or pert<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong>terests are not listed. These <strong>in</strong>clude stock hold<strong>in</strong>gs valued at less than US$ 10 000 overall and<br />

occasional travel grants totall<strong>in</strong>g less than 5% of time, and consult<strong>in</strong>g on non-regulatory matters totall<strong>in</strong>g less<br />

than 2% of time and compensation.<br />

Conflicts of <strong>in</strong>terest have been disclosed by the experts between October 2008 and October 2010. No other potential<br />

conflicts of <strong>in</strong>terest relevant to this publication were reported.<br />

2<br />

The Unit of <strong>cancer</strong> Epidemiology, Department of Oncology, CPO Piemonte (Piedmont Centre <strong>for</strong> Cancer Prevention)<br />

and S. Giovanni University Hospital where N. Segnan, P. Armaroli, R. Banzi, C. Bellisario, L. Giordano,<br />

S. M<strong>in</strong>ozzi and C. Senore are based was the co-recipient of a grant <strong>in</strong> 2006-2009 from the EU <strong>for</strong> development of<br />

<strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition V<br />

1<br />

FF

AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND REVIEWERS<br />

M<strong>in</strong> Dai, National Office <strong>for</strong> Cancer Prevention & Control<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beij<strong>in</strong>g, Ch<strong>in</strong>a<br />

John Daniel 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Marianna De Camargo Cancela 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Evelien Dekker, Academic Medical Centre <strong>in</strong> Amsterdam<br />

Amsterdam, the Netherlands<br />

Nad<strong>in</strong>e Delicata, National Breast Screen<strong>in</strong>g Centre<br />

Valleta, Malta<br />

Simon Ducarroz 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Henn<strong>in</strong>g Erfkampf, University of Applied Sciences FH Joanneum<br />

Graz, Austria<br />

Josep Esp<strong>in</strong>às Piñol, Catalan Cancer Plan<br />

L'Hospitalet de Llobregat, Spa<strong>in</strong><br />

Jean Faivre, Digestive Cancer Registry of Burgundy<br />

Dijon, France<br />

Lynn Faulds-Wood 4 , <strong>European</strong> Cancer Patient Coalition<br />

Twickenham, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Anath Flugelman, National Israeli Cancer Control Centre (NICCC)<br />

Haifa, Israel<br />

Snježana Frković-Grazio, Department of Pathology, Institute of Oncology<br />

Ljubljana, Slovenia<br />

Berta Geller, University of Vermont<br />

Burl<strong>in</strong>gton, Vermont, USA<br />

Livia Giordano 2 , CPO Piemonte<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

Grazia Grazz<strong>in</strong>i, CSPO Istituto Scientifico Regione Toscana<br />

Florence, Italy<br />

3<br />

The International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer (Lyon, France), where L. von Karsa, J. Daniel, M. De Camargo<br />

Cancela, S. Ducarroz, C. Herrmann, R. Lambert, T. Lign<strong>in</strong>i, E. Lucas, R. Muwonge, J. Ren, C. Sauvaget,<br />

D. Sighoko and L. Voti are based was the co-recipient of a grant <strong>in</strong> 2006-2009 from the EU <strong>for</strong> development of<br />

<strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

4<br />

The <strong>European</strong> Cancer Patient Coalition (ECPC), Utrecht, The Netherlands, was the co-recipient of a grant <strong>in</strong> 2006-<br />

2009 from the EU <strong>for</strong> development of <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g. Lynn Faulds<br />

Wood was President of the Coalition <strong>for</strong> the duration of the grant.<br />

VI <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND REVIEWERS<br />

Jane Green 5 , University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Stephen Halloran, Royal Surrey County Hospital - NHS Trust<br />

Guild<strong>for</strong>d, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Chisato Hamashima, National Cancer Centre<br />

Tokyo, Japan<br />

Christian Herrmann 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Paul Hewitson 5 , University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Geir Hoff, Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g Programme<br />

Oslo, Norway<br />

Iben Holten, Danish Cancer Society<br />

Copenhagen, Denmark<br />

Rodrigo Jover, Hospital General Universitario de Alicante<br />

Alicante, Spa<strong>in</strong><br />

Michal Kam<strong>in</strong>ski, Centre of Oncology Institute<br />

Warsaw, Poland<br />

Lawrence von Karsa 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Ernst Kuipers, Erasmus MC<br />

Rotterdam, the Netherlands<br />

Juozas Kurt<strong>in</strong>aitis † , Lithuanian Cancer Registry<br />

Vilnius, Lithuania<br />

René Lambert 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Iris Lansdorp-Vogelaar, Erasmus MC<br />

Rotterdam, the Netherlands<br />

Guy Launoy, INSERM<br />

Caen, France<br />

Won Chul Lee, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medic<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Seoul, Korea<br />

5 The University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d, with which J. Patnick is affiliated and where J. Green, P. Hewitson, P. Villa<strong>in</strong> and<br />

J. Watson are based was the co-recipient of a grant <strong>in</strong> 2006-2009 from the EU <strong>for</strong> development of <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition VII

AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND REVIEWERS<br />

Roger Leicester, St. George’s Hospital<br />

London, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Marcis Leja, University of Latvia<br />

Riga, Latvia<br />

David Lieberman, Oregon Health & Science University<br />

Portland, Oregon, USA<br />

Tracy Lign<strong>in</strong>i 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Eric Lucas 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Elsebeth Lynge, University of Copenhagen,<br />

Copenhagen, Denmark<br />

Szilvia Madai 6 , MaMMa Healthcare Institute<br />

Budapest, Hungary<br />

Nea Malila, F<strong>in</strong>nish Cancer Registry<br />

Hels<strong>in</strong>ki, F<strong>in</strong>land<br />

José Carlos Mar<strong>in</strong>ho, Health Adm<strong>in</strong>istration Central Region Portugal<br />

Aveiro, Portugal<br />

Giorgio M<strong>in</strong>oli, Italian Society of Gastroenterology<br />

Montorfano, Italy<br />

António Morais, Adm<strong>in</strong>istracai Regional Sude do Centro<br />

Coimbra, Portugal<br />

Sue Moss, The Institute of Cancer Research - Royal Cancer Hospital<br />

Sutton, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Richard Muwonge 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Marion Nadel, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centers <strong>for</strong> Disease Control and<br />

Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA<br />

Luciana Neamtiu, Institutul Oncologic “I. Chiricuta”<br />

Cluj, Romania<br />

Julietta Patnick 5 , NHS Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g Programmes<br />

Sheffield, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

6 The Public Association <strong>for</strong> Healthy People (PAHP), Budapest, Hungary with which S. Madai is affiliated was the corecipient<br />

of a grant <strong>in</strong> 2006-2009 from the EU <strong>for</strong> development of <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

VIII <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND REVIEWERS<br />

Mercè Peris Tuser, Cancer Prevention and Control Unit Catalan Cancer<br />

L'Hospitalet de Llobregat, Spa<strong>in</strong><br />

Michael Pignone, University of North Carol<strong>in</strong>a<br />

Chapel Hill, North Carol<strong>in</strong>a, USA<br />

Christian Pox, Mediz<strong>in</strong>ische Kl<strong>in</strong>ik – Ruh Universität<br />

Bochum, Germany<br />

Maja Primic-Žakelj, Epidemiology and Cancer Registries, Institute of Oncology<br />

Ljubljana, Slovenia<br />

Joseph Victor Psaila, M<strong>in</strong>istry of Health, the Elderly, and Community Care<br />

Valleta, Malta<br />

Phil Quirke, Leeds Institute of Molecular Medic<strong>in</strong>e – St James’ University Hospital<br />

Leeds, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

L<strong>in</strong>da Rabeneck, University of Toronto and Cancer Care Ontario<br />

Toronto, Canada<br />

David F. Ransohoff, University of North Carol<strong>in</strong>a at Chapel Hill<br />

Chapel Hill, North Carol<strong>in</strong>a, USA<br />

Morten Rasmussen, Bispebjerg University Hospital<br />

Copenhagen, Denmark<br />

Jaroslaw Regula, Maria Sklodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Centre<br />

Warsaw, Poland<br />

Jiansong Ren 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Gad Rennert, National Israeli Breast and Colorectal Cancer Detection<br />

Haifa, Israel<br />

Jean-François Rey 7 , Institut Arnault Tzanck<br />

St Laurent du Var, France<br />

Robert H. Riddell, Mount S<strong>in</strong>ai Hospital<br />

Toronto, Canada<br />

Mauro Risio, Institute <strong>for</strong> Cancer Research and Treatment<br />

Candiolo-Tor<strong>in</strong>o, Italy<br />

Vitor José Lopes Rodrigues, Breast Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g Programme<br />

Coimbra, Portugal<br />

Hiroshi Saito, Research Centre <strong>for</strong> Cancer Prevention and Screen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Tokyo, Japan<br />

7 J.-F. Rey is a recipient of research grants from a manufacturer of endoscopic equipment.<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition IX

AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND REVIEWERS<br />

Cather<strong>in</strong>e Sauvaget 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Astrid Scharpantgen, M<strong>in</strong>istry of Health<br />

Luxembourg, Luxembourg<br />

Wolff Schmiegel 8 , Ruhr Universität<br />

Bochum, Germany<br />

Nereo Segnan 2 , CPO Piemonte<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

Carlo Senore 2 , CPO Piemonte<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

Maqsood Siddiqi, Cancer Foundation of India<br />

Kolkata, India<br />

Dom<strong>in</strong>ique Sighoko 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Robert Smith, Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g, National Home Office, American Cancer Society<br />

Atlanta, Georgia, USA<br />

Steve Smith, University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire NHS Trust<br />

Coventry, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Robert J. Steele, N<strong>in</strong>ewells Hospital and Medical School<br />

Dundee, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Stepan Suchanek, Charles University and Central Military Hospital<br />

Prague, Czech Republic<br />

Eero Suonio, International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Wei-M<strong>in</strong> Tong, Department of Pathology, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Ch<strong>in</strong>ese<br />

Academy of Medical Sciences & Pek<strong>in</strong>g Union Medical College, Beij<strong>in</strong>g, Ch<strong>in</strong>a<br />

Sven Törnberg, Karol<strong>in</strong>ska University Hospital, Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g Unit<br />

Stockholm, Sweden<br />

Roland Valori, NHS Endoscopy<br />

Leicester, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Eric Van Cutsem, University of Leuven<br />

Leuven, Belgium<br />

8<br />

W. Schmiegel holds patents <strong>for</strong> substances used <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis but derives no<br />

<strong>in</strong>come from the patents.<br />

X <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND REVIEWERS<br />

Michael Vieth, Institute of Pathology, Kl<strong>in</strong>ikum Bayreuth<br />

Bayreuth, Germany<br />

Patricia Villa<strong>in</strong> 5 , University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Lydia Voti 3 , International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

Lyon, France<br />

Hidenobu Watanabe, Niigata University,<br />

Niigata, Japan<br />

Sidney J. W<strong>in</strong>awer, Memorial Sloan-Ketter<strong>in</strong>g Cancer Centre<br />

New York, New York, USA<br />

Graeme Young 9 , Gastro<strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al Services - Fl<strong>in</strong>ders University<br />

Adelaide, Australia<br />

Jožica Maučec Zakotnik, Health Care Centre<br />

Ljubljana, Slovenia<br />

Viaceslavas Zaksas, State Patient Fund<br />

Vilnius, Lithuania<br />

Marco Zappa, Centre <strong>for</strong> Study and Prevention of Cancer (CSPO)<br />

Florence, Italy<br />

9<br />

G. Young is the recipient of research funds deal<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g from a manufacturer of faecal<br />

immunochemical tests.<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition XI

AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, EDITORS AND REVIEWERS<br />

Literature Group<br />

Silvia M<strong>in</strong>ozzi 2 , CPO Piemonte<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

Paola Armaroli 2 , CPO Piemonte<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

Rita Banzi 2 , CPO Piemonte<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

Crist<strong>in</strong>a Bellisario 2 , CPO Piemonte<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

Paul Hewitson 5 , University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Clare Monk, Imperial College,<br />

London, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Carlo Senore 2 , CPO Piemonte<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

Patricia Villa<strong>in</strong> 5 , University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Luca Vignatelli, AUSL Bologna<br />

Bologna, Italy<br />

Joanna Watson 5 , University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d, United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<br />

Nereo Segnan 2 , CPO Piemonte<br />

Tur<strong>in</strong>, Italy<br />

XII <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

Prefaces

PREFACE<br />

Preface<br />

John Dalli*<br />

Colorectal <strong>cancer</strong> is the second most common newly diagnosed <strong>cancer</strong> and the second most common<br />

cause of <strong>cancer</strong> death <strong>in</strong> the EU. Many of these deaths, however, could be avoided through early<br />

detection, by mak<strong>in</strong>g effective use of screen<strong>in</strong>g tests followed by appropriate treatment.<br />

For this reason, the evidence-based <strong>European</strong> Code Aga<strong>in</strong>st Cancer recommends that men and<br />

women from 50 years of age should participate <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g. This has been given effect<br />

with<strong>in</strong> the EU by the 2003 Council Recommendation on <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g. Mak<strong>in</strong>g this screen<strong>in</strong>g effective,<br />

<strong>in</strong> turn, depends on appropriate <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> at all levels.<br />

That is the aim of the "<strong>European</strong> Guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>for</strong> Quality Assurance <strong>in</strong> Colorectal Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

Diagnosis". These <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong>, the result of tireless ef<strong>for</strong>ts over many years by a wide range of <strong>European</strong><br />

experts, represent a major achievement, with the potential to add substantial value to the<br />

ef<strong>for</strong>ts of the Member States to improve control of <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>.<br />

This, <strong>in</strong> turn, will save lives and help improve the <strong>quality</strong> of life of millions of EU citizens, their families<br />

and friends.<br />

This publication will ensure that any organisation, programme or authority <strong>in</strong> the Member States, as<br />

well as every <strong>European</strong> citizen, can ga<strong>in</strong> access to the recommended standards and procedures. It<br />

represents a concrete contribution by the <strong>European</strong> Commission to our shared <strong>European</strong> objective of<br />

prevent<strong>in</strong>g human illness and disease.<br />

I should like to thank the editors, authors, contributors and reviewers of these <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> assembl<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

analys<strong>in</strong>g and document<strong>in</strong>g the enormous quantity of evidence on which this volume has been<br />

based. I am confident that it will become an <strong>in</strong>dispensable guide <strong>for</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the<br />

com<strong>in</strong>g years.<br />

Brussels, July 2010<br />

*<strong>European</strong> Commissioner <strong>for</strong> Health and Consumer Policy<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition XV

PREFACE<br />

Preface<br />

Christopher Wild*<br />

Colorectal <strong>cancer</strong> is the third most common <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>cidence and the fourth most common cause of <strong>cancer</strong><br />

death worldwide, with an estimated 1.2 million new cases and 609 000 deaths <strong>in</strong> 2008. Based on<br />

demographic trends, the annual <strong>in</strong>cidence is expected to <strong>in</strong>crease by nearly 80% to 2.2 million cases<br />

over the next two decades and most of this <strong>in</strong>crease will occur <strong>in</strong> the less developed regions of the<br />

world. These regions are ill equipped to deal with the rapidly <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g demand <strong>for</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> treatment<br />

result<strong>in</strong>g from population growth and higher life expectancy. Even greater <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> the worldwide<br />

burden of the disease can be expected if less developed regions adopt a more “westernised” life style.<br />

Concerted ef<strong>for</strong>ts to control <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> are there<strong>for</strong>e of <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g importance worldwide.<br />

Fortunately, experience <strong>in</strong> Europe has shown that systematic early detection and treatment of <strong>colorectal</strong><br />

lesions be<strong>for</strong>e they become symptomatic has the potential to improve control of the disease, particularly<br />

if they are effectively <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to an overall programme of comprehensive <strong>cancer</strong> control.<br />

Coord<strong>in</strong>ated resources are needed not only <strong>for</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and primary prevention programmes but<br />

also <strong>for</strong> further development and capacity build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> diagnosis and therapy of <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>,<br />

especially <strong>in</strong> the less developed regions of the world because of the expected changes mentioned<br />

above. Political commitment and appropriate <strong>in</strong>vestment at an early stage are not only likely to lower<br />

the future burden of disease, but also to save considerable resources when organised, populationbased<br />

programmes are fully established.<br />

The authors and editors of the new <strong>European</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> have taken care to po<strong>in</strong>t<br />

out that organised as opposed to “opportunistic” screen<strong>in</strong>g programmes are recommended because<br />

they <strong>in</strong>clude an adm<strong>in</strong>istrative structure responsible <strong>for</strong> programme implementation, <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong><br />

and evaluation. Population-based programmes generally require a high degree of organisation <strong>in</strong> order<br />

to identify and personally <strong>in</strong>vite each person <strong>in</strong> the eligible target population. Personal <strong>in</strong>vitation aims<br />

to give each eligible person an equal chance of benefit<strong>in</strong>g from screen<strong>in</strong>g and to thereby reduce<br />

health <strong>in</strong>equalities. These ef<strong>for</strong>ts should be supported by effective communication <strong>for</strong> groups with limited<br />

access to screen<strong>in</strong>g, such as less advantaged socio-economic groups. This, <strong>in</strong> turn, should permit<br />

an <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>med decision about participation, based on objective, balanced <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation about the risks and<br />

benefits of screen<strong>in</strong>g. The population-based approach to programme implementation is also recommended<br />

because it provides an organisational framework <strong>for</strong> effective management and cont<strong>in</strong>uous<br />

improvement of the screen<strong>in</strong>g process, such as through l<strong>in</strong>kage with population CregistersC and <strong>cancer</strong><br />

registries <strong>for</strong> optimization of <strong>in</strong>vitation to screen<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>for</strong> evaluation of screen<strong>in</strong>g per<strong>for</strong>mance and<br />

impact respectively. In this context research after implementation of screen<strong>in</strong>g should be an <strong>in</strong>tegral<br />

part of population-based programmes.<br />

Crucial to the success of any <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g programme is the availability of comprehensive, evidence-based<br />

<strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong>, address<strong>in</strong>g all of the steps <strong>in</strong> the screen<strong>in</strong>g process, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g<br />

not just per<strong>for</strong>mance of a test, but also <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation and <strong>in</strong>vitation, diagnostic work-up of lesions<br />

detected <strong>in</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g, treatment, surveillance and any other subsequent care. Widespread application<br />

of the standardised <strong>in</strong>dicators recommended <strong>in</strong> the Guidel<strong>in</strong>es will facilitate <strong>quality</strong> management and<br />

promote the <strong>in</strong>ternational exchange of <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation and experience between programmes that is essential<br />

<strong>for</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>uous <strong>quality</strong> improvement.<br />

XVI <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

PREFACE<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, as Director of an <strong>in</strong>ternational agency I would like to highlight the outstand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ternational<br />

cooperation that has gone <strong>in</strong>to the preparation of these Guidel<strong>in</strong>es. But also, as the landscape of <strong>cancer</strong><br />

occurrence evolves to cast the burden of <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> on new regions fac<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cidence<br />

rates due to an ag<strong>in</strong>g population and “westernised” life style, it is vital that the excellence demonstrated<br />

here is pursued and translated to appropriate guidance <strong>for</strong> the widest possible audience on<br />

a global scale.<br />

Lyon, October 2010<br />

*Director, International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition XVII

PREFACE<br />

Preface<br />

Jean-François Rey, Colm O’Mora<strong>in</strong>, René Lambert<br />

Quality <strong>assurance</strong> has always been a key issue <strong>in</strong> digestive endoscopy. Fortunately, this important<br />

topic has recently also been placed high on the agenda of the health authorities, healthcare providers<br />

and patient associations. A major reason <strong>for</strong> this is the <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g awareness that effective screen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

programmes will have a vital role to play <strong>in</strong> help<strong>in</strong>g to cope with grow<strong>in</strong>g problem of <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> Europe. Effective screen<strong>in</strong>g should supplement ongo<strong>in</strong>g ef<strong>for</strong>ts to improve primary prevention, as<br />

well as the diagnosis and therapy of symptomatic disease. However, the potential of screen<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

reduce the burden of the most common <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>in</strong> Europe will require an enormous expansion <strong>in</strong> the<br />

number of people attend<strong>in</strong>g national programmes. That <strong>in</strong> turn will require substantial resources and<br />

expanded ef<strong>for</strong>ts <strong>in</strong> the field of <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong>.<br />

Colonoscopy plays a key role <strong>in</strong> every <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g programme because it is the gold<br />

standard by which the status of people with positive screen<strong>in</strong>g tests is evaluated. The same applies to<br />

patients <strong>in</strong> a symptomatic service. As po<strong>in</strong>ted out <strong>in</strong> the new <strong>European</strong> Guidel<strong>in</strong>es, ef<strong>for</strong>ts to improve<br />

<strong>quality</strong> and expand screen<strong>in</strong>g should be well planned and should lead to improvement not just <strong>in</strong><br />

screen<strong>in</strong>g, but also <strong>in</strong> symptomatic care. These ef<strong>for</strong>ts should also have a positive impact on the<br />

availability of high <strong>quality</strong> endoscopy <strong>for</strong> symptomatic services, by provid<strong>in</strong>g sufficient resources to<br />

achieve and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> appropriate wait<strong>in</strong>g times.<br />

The <strong>in</strong>ternational collaboration and cooperation <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g the new <strong>European</strong> Guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong><br />

<strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis has also shown that additional tools are now<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g developed to assist gastroenterologists <strong>in</strong> evaluat<strong>in</strong>g their current level of per<strong>for</strong>mance <strong>in</strong><br />

screen<strong>in</strong>g. It should be kept <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, however, that these <strong>in</strong>itiatives, though important, can only be<br />

effective if they stimulate action to cont<strong>in</strong>uously improve and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> high levels of professional per<strong>for</strong>mance.<br />

The follow<strong>in</strong>g factors rema<strong>in</strong> fundamental to achiev<strong>in</strong>g high <strong>quality</strong> <strong>in</strong> endoscopy:<br />

Thorough cleans<strong>in</strong>g of the large bowel is the first mandatory step. If the endoscopist’s vision is<br />

obscured, small or flat lesions anywhere <strong>in</strong> the colon and particularly sessile lesions <strong>in</strong> the right colon<br />

may go undetected.<br />

Patient tolerance and acceptance of the endoscopic exam<strong>in</strong>ation is also of prime importance and can<br />

be <strong>in</strong>creased by sedation. National or cultural differences <strong>in</strong> this doma<strong>in</strong> should be taken <strong>in</strong>to account.<br />

Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, adequate equipment and external evaluation of endoscopy units has proved to be essential<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g the start-up of a national screen<strong>in</strong>g programme. Such activities are likely to play an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly<br />

important role <strong>in</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> of symptomatic endoscopy <strong>in</strong> the com<strong>in</strong>g years.<br />

Nice, Ireland, Lyon, October 2010<br />

Jean-François Rey Colm O’Mora<strong>in</strong> René Lambert<br />

Co-author President Elect, UEGF Council Co-author<br />

Institut Arnault Tzanck Tr<strong>in</strong>ity College Dubl<strong>in</strong> International Agency <strong>for</strong><br />

Research on Cancer<br />

XVIII <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

PREFACE<br />

Preface<br />

J Patnick, N Segnan, L von Karsa (Editors)<br />

The editorial board would like to thank all the authors, reviewers and other contributors who have<br />

worked so hard to develop these first Guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>for</strong> the new <strong>colorectal</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

programmes which are emerg<strong>in</strong>g across the EU. This has been a major undertak<strong>in</strong>g s<strong>in</strong>ce many of<br />

these chapters broke new ground <strong>in</strong> <strong>European</strong> collaboration and challenged established practice. The<br />

chapters have been produced to a new evidence-based protocol that will, from now on, be used<br />

across all EU <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> and this also presented the authors and reviewers with fresh<br />

challenges.<br />

It is, however, fair to say that the production has been a very stimulat<strong>in</strong>g experience to those<br />

<strong>in</strong>volved, and the evolution of the <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> created strong bonds <strong>for</strong> future jo<strong>in</strong>t work<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

The <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> are designed to ensure that <strong>in</strong> the future each Member State can deliver screen<strong>in</strong>g to a<br />

high standard even if they are at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of a screen<strong>in</strong>g programme. There is another thank<br />

you due. This is to the citizens of the EU and those patients on whose past experiences of screen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and endoscopy these <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> are based.<br />

Ox<strong>for</strong>d, Tur<strong>in</strong>, Lyon, October 2010<br />

Julietta Patnick<br />

Director, NHS Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g Programmes<br />

Visit<strong>in</strong>g Professor, Cancer Screen<strong>in</strong>g Research Unit<br />

University of Ox<strong>for</strong>d<br />

Nereo Segnan<br />

Director, Unit of Cancer Epidemiology<br />

CPO Piemonte and AOU San Giovanni Battista Hospital<br />

Lawrence von Karsa<br />

Head, Quality Assurance Group<br />

Section of Early Detection and Prevention<br />

International Agency <strong>for</strong> Research on Cancer<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition XIX

PREFACE<br />

XX <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

Table of contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Tablle of contents<br />

List of editors III<br />

List of authors, contributors, editors and reviewers V<br />

Literature Group XII<br />

Prefaces XIII<br />

Executive summary XXXV<br />

Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of evidence assessment and methods <strong>for</strong> reach<strong>in</strong>g<br />

recommendations XLIX<br />

In I tt rroduc tt ion i<br />

1<br />

Guid<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciples 3<br />

Recommendations and conclusions 4<br />

1.1 Background 6<br />

1.1.1 Colorectal <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>in</strong> Europe 6<br />

1.1.2 Population screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> 7<br />

1.1.3 Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of population screen<strong>in</strong>g 7<br />

1.1.4 EU policy on <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g 9<br />

1.1.5 Implementation of <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Europe 11<br />

1.2 Evidence <strong>for</strong> effectiveness of FOBT screen<strong>in</strong>g 12<br />

1.2.1 Guaiac FOBT 12<br />

1.2.1.1 Evidence <strong>for</strong> efficacy 12<br />

1.2.1.2 Evidence <strong>for</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terval 12<br />

1.2.1.3 Evidence <strong>for</strong> the age range 13<br />

1.2.1.4 Evidence on risks vs. benefit and cost-effectiveness 14<br />

1.2.2 Immunochemical FOBT 14<br />

1.2.2.1 Evidence <strong>for</strong> efficacy 14<br />

1.2.2.2 Evidence <strong>for</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terval 15<br />

1.2.2.3 Evidence <strong>for</strong> the age range 15<br />

1.2.2.4 Evidence on risks vs. benefit and cost-effectiveness 15<br />

1.3 Evidence <strong>for</strong> effectiveness of endoscopy screen<strong>in</strong>g 16<br />

1.3.1 Sigmoidoscopy 16<br />

1.3.1.1 Evidence <strong>for</strong> efficacy 16<br />

1.3.1.2 Evidence <strong>for</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terval 17<br />

1.3.1.3 Evidence <strong>for</strong> the age range 18<br />

1.3.1.4 Evidence on risks vs. benefit and cost-effectiveness 18<br />

1.3.2 Colonoscopy 19<br />

1.3.2.1 Evidence <strong>for</strong> efficacy 19<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition XXIII

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

1.3.2.2 Evidence <strong>for</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terval 20<br />

1.3.2.3 Evidence <strong>for</strong> the age range 20<br />

1.3.2.4 Evidence on risks vs. benefit and cost-effectiveness 20<br />

1.4 Evidence <strong>for</strong> effectiveness of FOBT and sigmoidoscopy<br />

comb<strong>in</strong>ed 21<br />

1.5 New screen<strong>in</strong>g technologies under evaluation 22<br />

1.5.1 CT colonography 22<br />

1.5.2 Stool DNA 23<br />

1.5.3 Capsule endoscopy 23<br />

1.6 References 24<br />

O rrgan isa i tt ion i<br />

33<br />

Guid<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>for</strong> organis<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g<br />

programme 35<br />

Recommendations and conclusions 36<br />

2.1 Introduction 39<br />

2.2 Organised vs. non-organised screen<strong>in</strong>g 39<br />

2.2.1 Opportunistic screen<strong>in</strong>g or case-f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g 40<br />

2.2.2 Comparison of coverage and effectiveness 40<br />

2.2.3 Prerequisites <strong>for</strong> organised screen<strong>in</strong>g 40<br />

2.3 Implement<strong>in</strong>g the screen<strong>in</strong>g programme 42<br />

2.3.1 Identify<strong>in</strong>g and def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the target population 42<br />

2.3.1.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria 43<br />

2.3.1.2 Family history 43<br />

2.4 Participation <strong>in</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g 44<br />

2.4.1 Barriers 44<br />

2.4.2 Interventions to promote participation 45<br />

2.4.2.1 Remov<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>ancial barriers 45<br />

2.4.3 Invitation 46<br />

2.4.3.1 Invitation letter 46<br />

2.4.3.2 Rem<strong>in</strong>ders 46<br />

2.4.3.3 Deliver<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation about screen<strong>in</strong>g 47<br />

2.4.3.3.1 In<strong>for</strong>mation conveyed with the <strong>in</strong>vitation (see also Chapter 10) 47<br />

2.4.3.4 The role of primary care providers 48<br />

2.4.3.4.1 Role of GPs/family physicians 48<br />

2.4.3.4.2 Interventions aimed to promote provider <strong>in</strong>volvement (See also Chapter 10) 49<br />

2.5 Test<strong>in</strong>g protocol 50<br />

2.5.1 FOBT 50<br />

XXIV <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

2.5.1.1 Delivery of kits and collection of stool samples (see also Chapter 4) 50<br />

2.5.1.2 Per<strong>for</strong>m<strong>in</strong>g the test: dietary restrictions and number of samples 51<br />

2.5.1.3 Exam<strong>in</strong>ation of the samples, test <strong>in</strong>terpretation and report<strong>in</strong>g 51<br />

2.5.2 Endoscopy 52<br />

2.5.2.1 Obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g bowel preparation <strong>for</strong> endoscopy screen<strong>in</strong>g 52<br />

2.5.2.2 Bowel preparation <strong>for</strong> sigmoidoscopy (see also Chapter 5) 53<br />

2.5.2.3 Bowel preparation <strong>for</strong> colonoscopy (see also Chapter 5) 53<br />

2.5.2.4 Test <strong>in</strong>terpretation and report<strong>in</strong>g 54<br />

2.5.2.4.1 Inadequate test 54<br />

2.5.2.4.2 Def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a negative test and episode result 54<br />

2.5.3 Management of people with positive test results and fail-safe<br />

mechanisms 54<br />

2.5.4 Follow-up of population and <strong>in</strong>terval <strong>cancer</strong>s (see also Chapter 3) 55<br />

2.6 Screen<strong>in</strong>g policy with<strong>in</strong> the healthcare system 56<br />

2.6.1 Local conditions at the start of a programme 56<br />

2.6.2 Def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the relevant healthcare professional and facilities 57<br />

2.6.2.1 Diagnostic and treatment centres 57<br />

2.6.2.2 Public health specialists 57<br />

2.6.3 What factors should be considered when decid<strong>in</strong>g which primary test<br />

to use? 58<br />

2.6.3.1 Gender and age differences (see also Chapter 1) 58<br />

2.6.3.2 Participation 58<br />

2.6.3.3 Screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terval and neoplasia detection rates accord<strong>in</strong>g to the site<br />

distribution (see also Chapter 1) 59<br />

2.6.3.4 Cost-effectiveness (see also Chapter 1) 59<br />

2.6.3.5 Resources and susta<strong>in</strong>ability of the programme 60<br />

2.6.4 Implementation period (step-wise) 60<br />

2.6.5 Data collection and monitor<strong>in</strong>g (see also Chapter 3) 61<br />

2.6.5.1 Data sources 61<br />

2.6.5.2 How to respond to outcomes of monitor<strong>in</strong>g 62<br />

2.7 References 63<br />

Eva lua l tt ion i and <strong>in</strong> i tte rrp rre tta tt ion i o ff sc rreen <strong>in</strong>g i<br />

ou ttcomes 71<br />

Recommendations 73<br />

3.1 Introduction 75<br />

3.2 Data items necessary <strong>for</strong> evaluation 76<br />

3.2.1 Programme conditions 76<br />

3.2.2 Invitation variables 77<br />

3.2.3 Process variables of primary screen<strong>in</strong>g and follow up 77<br />

3.2.3.1 Process variables <strong>in</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g with the faecal occult blood test (FOBT) and<br />

other <strong>in</strong> vitro tests 77<br />

3.2.3.2 Variables <strong>in</strong> endoscopic screen<strong>in</strong>g 78<br />

3.2.4 Programme outcome variables 79<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition XXV

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

3.2.5 Data tables 80<br />

3.3 Early per<strong>for</strong>mance <strong>in</strong>dicators 81<br />

3.3.1 Programme coverage and uptake 83<br />

3.3.2 Outcomes with faecal occult blood test<strong>in</strong>g (FOBT) <strong>for</strong> primary<br />

screen<strong>in</strong>g 84<br />

3.3.3 Outcomes with flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) or colonoscopy (CS) as<br />

primary screen<strong>in</strong>g tests 90<br />

3.3.4 Screen<strong>in</strong>g organisation 95<br />

3.4 Long-term impact <strong>in</strong>dicators 96<br />

3.4.1 Interval <strong>cancer</strong>s 97<br />

3.4.2 CRC <strong>in</strong>cidence rates 98<br />

3.4.3 Rates of advanced-stage disease 98<br />

3.4.4 CRC mortality rates 98<br />

3.5 References 100<br />

Faeca l<br />

Occu l tt<br />

Blood l<br />

Tes tt <strong>in</strong>g i<br />

103<br />

Recommendations 105<br />

4.1 Introduction 109<br />

4.2 Biochemical tests <strong>for</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> 110<br />

4.2.1 Characteristics of a test <strong>for</strong> population-screen<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> 110<br />

4.2.2 Faecal blood loss 111<br />

4.2.3 Sample collection <strong>for</strong> Faecal Occult Blood Test devices 111<br />

4.2.4 Guaiac Faecal Occult Blood Test - gFOBT 112<br />

4.2.5 Immunochemical tests - iFOBTs 113<br />

4.2.6 Other tests 114<br />

4.2.7 Recommendations 115<br />

4.3 Analytical characteristics and per<strong>for</strong>mance 116<br />

4.3.1 Analytical sensitivity 116<br />

4.3.1.1 Analytical sensitivity and cut-off limits 116<br />

4.3.2 Analytical specificity and <strong>in</strong>terference 117<br />

4.3.2.1 Analytical <strong>in</strong>terference 117<br />

4.3.2.2 Biological <strong>in</strong>terference 118<br />

4.3.2.3 Dietary and drug restrictions 120<br />

4.3.3 Other factors <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g analytical per<strong>for</strong>mance 121<br />

4.3.3.1 Prozone effect 121<br />

4.3.3.2 Sample <strong>quality</strong> 121<br />

4.3.3.3 Device consistency 122<br />

4.3.3.4 Analytical <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> – Internal Quality Control (IQC) and External<br />

Quality Assessment Schemes (EQAS) 122<br />

4.3.4 Recommendations 126<br />

4.4 Cl<strong>in</strong>ical per<strong>for</strong>mance 128<br />

XXVI <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

4.4.1 Description of terms used to describe test effectiveness 128<br />

4.4.2 Comparative cl<strong>in</strong>ical per<strong>for</strong>mance - gFOBT and iFOBT 130<br />

4.4.3 Optimis<strong>in</strong>g cl<strong>in</strong>ical per<strong>for</strong>mance us<strong>in</strong>g test cut-off limits & algorithms 133<br />

4.4.3.1 Cut-off limits 133<br />

4.4.3.2 Number of stool specimens 133<br />

4.4.3.3 Sequential test<strong>in</strong>g 136<br />

4.4.3.4 Participation rate and choice of test 136<br />

4.4.4 Recommendations 136<br />

4.5 Conclusions 137<br />

4.6 References 138<br />

Qua l i tty assu rrance <strong>in</strong> i endoscopy<br />

cance rr sc rreen <strong>in</strong>g i and diagnos i is i<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition XXVII<br />

<strong>in</strong> i<br />

colo l rrec tta l<br />

145<br />

Guid<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>for</strong> a <strong>colorectal</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g endoscopy service 147<br />

Recommendations 148<br />

5.1 Effect of screen<strong>in</strong>g modality on the provision of endoscopic<br />

services <strong>for</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g 151<br />

5.1.1 Cl<strong>in</strong>ical sett<strong>in</strong>g 151<br />

5.1.2 Quality and safety 151<br />

5.1.3 The need <strong>for</strong> sedation 153<br />

5.1.4 Patient considerations 154<br />

5.1.5 Possible destabilis<strong>in</strong>g effect on symptomatic services 154<br />

5.1.6 Infrastructure and efficiency 154<br />

5.1.7 Endoscopist and support staff competencies 154<br />

5.1.8 Support services 155<br />

5.1.9 Conclusion 155<br />

5.2 Audit and <strong>quality</strong> improvement 155<br />

5.3 Be<strong>for</strong>e the procedure 156<br />

5.3.1 Patient <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation and consent 156<br />

5.3.2 Pre-assessment 157<br />

5.3.3 Colonic cleans<strong>in</strong>g 157<br />

5.3.4 Schedul<strong>in</strong>g and choice 159<br />

5.3.5 Timel<strong>in</strong>es 159<br />

5.3.6 Environment 159<br />

5.4 Dur<strong>in</strong>g the procedure 160<br />

5.4.1 Cleans<strong>in</strong>g and dis<strong>in</strong>fection 160<br />

5.4.2 Kit - technologies <strong>for</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>sertion of the colonoscope 161<br />

5.4.3 Kit – techniques and technologies to enhance detection,<br />

characterisation and removal of high-risk lesions 161<br />

5.4.4 Sedation and com<strong>for</strong>t 164<br />

5.4.5 Endoscopist techniques and per<strong>for</strong>mance 166<br />

5.4.5.1 Quality outcomes 166<br />

5.4.5.2 Safety outcomes 169

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

5.5 After the procedure 170<br />

5.5.1 Recovery facilities and procedures 170<br />

5.5.2 Emergency equipment and protocols 170<br />

5.5.3 Patient <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation – post procedure 170<br />

5.5.4 Patient feedback 170<br />

5.5.5 Communication to other health professionals 171<br />

5.5.6 Immediate and late safety outcomes 171<br />

5.6 Guidel<strong>in</strong>es 171<br />

5.7 Policies and processes 172<br />

5.8 References 173<br />

Annex 5.1 Suggested <strong>quality</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicators and auditable outcomes 179<br />

Annex 5.2 M<strong>in</strong>imum requirements <strong>for</strong> endoscopic report<strong>in</strong>g 183<br />

P rro ffess iona i l<br />

rrequ i rremen tts<br />

and<br />

tt rra <strong>in</strong> i <strong>in</strong>g i<br />

187<br />

Recommendations 189<br />

6.1 Introduction 191<br />

6.2 General requirements 191<br />

6.3 Adm<strong>in</strong>istrative and clerical staff 193<br />

6.4 Epidemiologist 194<br />

6.5 Laboratory staff 195<br />

6.6 Primary care physicians 196<br />

6.7 Endoscopists 197<br />

6.8 Radiologists 199<br />

6.9 Pathologists 199<br />

6.10 Surgeons 201<br />

6.11 Nurses 202<br />

6.12 Public health 202<br />

6.13 References 204<br />

XXVIII <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Qua l i tty assu rrance <strong>in</strong> i pa ttho logy l <strong>in</strong> i colo l rrec tta l<br />

cance rr sc rreen <strong>in</strong>g i and diagnos i is i<br />

205<br />

Recommendations 207<br />

7.1 Introduction 209<br />

7.2 Classification of lesions <strong>in</strong> the adenoma-carc<strong>in</strong>oma sequence 210<br />

7.2.1 Measurement of size of adenomas 210<br />

7.2.2 Tubular, tubulo-villous and villous adenomas: the typ<strong>in</strong>g of<br />

villousness 211<br />

7.2.3 Non-polypoid adenomas 211<br />

7.2.4 Serrated lesions 212<br />

7.2.4.1 Term<strong>in</strong>ology 212<br />

7.2.4.2 Hyperplastic (metaplastic) polyp 212<br />

7.2.4.3 Sessile serrated lesions 212<br />

7.2.4.4 Traditional serrated adenomas 213<br />

7.2.4.5 Mixed polyp 213<br />

7.3 Grad<strong>in</strong>g of neoplasia 213<br />

7.3.1 Low-grade neoplasia 213<br />

7.3.2 High-grade neoplasia 214<br />

7.4 Other lesions 216<br />

7.4.1 Inflammatory polyps 216<br />

7.4.2 Juvenile polyps 216<br />

7.4.3 Peutz-Jeghers polyps 216<br />

7.4.4 Serrated (hyperplastic) polyposis 217<br />

7.4.5 Cronkhite-Canada syndrome 217<br />

7.4.6 Neuroendocr<strong>in</strong>e tumour 217<br />

7.4.7 Colorectal <strong>in</strong>tramucosal tumours with epithelial entrapment and<br />

surface serration 217<br />

7.4.8 Non epithelial polyps 217<br />

7.5 Assessment of the degree of <strong>in</strong>vasion of pT1 <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> 218<br />

7.5.1 Def<strong>in</strong>ition of <strong>in</strong>vasion 218<br />

7.5.2 Epithelial misplacement 218<br />

7.5.3 High risk pT1 adenocarc<strong>in</strong>oma 219<br />

7.5.3.1 Sub-stag<strong>in</strong>g pT1 219<br />

7.5.3.2 Tumour grade <strong>in</strong> pT1 lesions 220<br />

7.5.3.3 Lymphovascular <strong>in</strong>vasion <strong>in</strong> pT1 adenocarc<strong>in</strong>omas 220<br />

7.5.3.4 Marg<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> pT1 adenocarc<strong>in</strong>omas 221<br />

7.5.3.5 Tumour cell budd<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> pT1 adenocarc<strong>in</strong>omas 221<br />

7.5.3.6 Site 221<br />

7.6 Specimen handl<strong>in</strong>g 221<br />

7.6.1 Submission of specimens 222<br />

7.6.2 Fixation 222<br />

7.6.3 Dissection 222<br />

7.6.3.1 Polypoid lesions 222<br />

7.6.3.2 Mucosal excisions 222<br />

7.6.3.3 Piecemeal removal 223<br />

<strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition XXIX

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

7.6.4 Section<strong>in</strong>g and levels 223<br />

7.6.5 Surgically-removed lesions 223<br />

7.6.5.1 Classification 223<br />

7.6.5.2 Practical issues 226<br />

7.7 Standards and <strong>quality</strong> <strong>in</strong>dicators 226<br />

7.8 Data collection and monitor<strong>in</strong>g 227<br />

7.9 Images 228<br />

7.10 References 229<br />

Annex<br />

--<br />

Anno tta tt ions i<br />

o ff<br />

colo l rrec tta l<br />

les l ions i<br />

233<br />

7A.1 Introduction 235<br />

7A.2 Grad<strong>in</strong>g of neoplasia 235<br />

7A.3 Classification of serrated lesions 236<br />

7A.3.1 Term<strong>in</strong>ology 236<br />

7A.3.2 Hyperplastic polyp 237<br />

7A.3.3 Sessile serrated lesion 238<br />

7A.3.4 Traditional serrated adenoma 240<br />

7A.3.5 Mixed polyp 241<br />

7A.3.6 Risk of progression 241<br />

7A.4 Assessment of T1 adenocarc<strong>in</strong>oma 241<br />

7A.4.1 Size 242<br />

7A.4.2 Tumour grade 242<br />

7A.4.3 Budd<strong>in</strong>g 242<br />

7A.4.4 Site 242<br />

7A.4.5 Def<strong>in</strong>ition of <strong>in</strong>vasion 244<br />

7A.5 References 246<br />

Managemen tt o ff les l ions i de ttec tted <strong>in</strong> i co llo rrec tta ll<br />

cance rr sc rreen <strong>in</strong>g i<br />

251<br />

Recommendations 253<br />

8.1 Introduction 256<br />

8.2 General requirements <strong>for</strong> treatment of <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>s and<br />

pre-malignant lesions 256<br />

8.3 Management of pre-malignant <strong>colorectal</strong> lesions 257<br />

8.3.1 Small lesions 257<br />

XXX <strong>European</strong> <strong>guidel<strong>in</strong>es</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>quality</strong> <strong>assurance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>colorectal</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> screen<strong>in</strong>g and diagnosis - First edition

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

8.3.2 Pedunculated adenomas/polyps 258<br />

8.3.3 Large sessile colonic adenomas/lesions 258<br />

8.3.4 Large sessile rectal adenomas/lesions 258<br />

8.3.5 Retrieval of lesions 259<br />

8.3.6 Management of <strong>in</strong>complete endoscopic excision 259<br />

8.3.7 Management of pre-malignant lesions <strong>in</strong> patients tak<strong>in</strong>g anticoagulants/anti-aggregants<br />

259<br />

8.3.8 Synopsis 260<br />

8.4 Management of pT1 <strong>cancer</strong>s 261<br />

8.4.1 Primary management 261<br />

8.4.2 Completion surgery 262<br />

8.4.3 Follow-up 262<br />

8.4.4 Synopsis 263<br />