Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

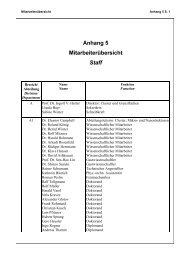

Fig. 35<br />

James Franck, <strong>Max</strong><br />

<strong>Born</strong>’s friend, carrying<br />

Gustav <strong>Born</strong>, aged<br />

around four.<br />

ned by other refugees including Einstein. As it turned out my parents were fully justified in this<br />

difficult decision. Their achievements have been enduringly effective. Deeply impressed myself,<br />

I have tried in small ways to continue their work, inter alia by working for the two large and<br />

excellent secondary schools in Munich and near Stuttgart named after <strong>Max</strong> <strong>Born</strong> [30-33].<br />

In a book of essays entitled The Luxury of a Conscience, actually in German, my parents wrote<br />

about their respective relationships with Einstein, my father mainly about their scientific discussions<br />

and my mother about Einstein the private person. <strong>Max</strong>’s article ends: “I know what it<br />

means to have been his friend”; and Hedi’s: “Now his living voice is silent, but those who heard<br />

it will hear it to the end of their days”.<br />

The famous divergence between Einstein and <strong>Max</strong> <strong>Born</strong> in their basic scientific tenets in no way<br />

diminished their mutual respect and affection. As Bertrand Russell comments, both were humble<br />

as well as brilliant, so that opposing convictions did not make them think less of the other.<br />

The divergence was of course the unwillingness of Einstein to accept that which <strong>Max</strong> <strong>Born</strong> evidently<br />

considered his most important contribution to science, namely the statistical interpretation<br />

of quantum mechanics (<strong>Born</strong>, 1955). Those words form the title of his Nobel Lecture given<br />

this day fifty years ago, from which I should like to quote the first paragraph: “The published<br />

work for which the honour of the Nobel Prize for the year 1954 has been accorded to me does<br />

not contain the discovery of a new phenomenon of nature, but, rather, the foundations of a<br />

new way of thinking about the phenomena of nature. This way of thinking has permeated<br />

experimental and theoretical physics to such an extent that it seems scarcely possible to say<br />

anything more about it that has not often been said already”. <strong>Max</strong> describes how he arrived at<br />

the necessity to abandon classical physics and the naïve conception of reality, which is to think<br />

of the particles of atomic physics as if they were exceedingly small grains of sand, with at each<br />

instance a definite position and velocity. For an electron this is not the case: if one determines<br />

the position with increasing accuracy the accuracy of determining the velocity becomes less,<br />

and vice versa. Through investigations involving collision theory he reached the point of saying:<br />

“One gets no answer to the question ‘what is the state after the collision”? but only to the<br />

question “how probable is a specific outcome of the collision’?” He proposed that electron<br />

waves were not continuous clouds of electricity, as Schrödinger interpreted them, but instead<br />

represented the probability of finding a particle in a certain place after a collision. <strong>Born</strong> concluded<br />

that the motion of particles follows probability rules, but that the probability itself conforms<br />

to causality. To quote Nancy Greenspans’s biography: “Causality had been the basis of the laws<br />

<strong>Max</strong> <strong>Born</strong> • Gustav <strong>Born</strong> 19