Layout 8 (Page 1) - Winston Churchill

Layout 8 (Page 1) - Winston Churchill

Layout 8 (Page 1) - Winston Churchill

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

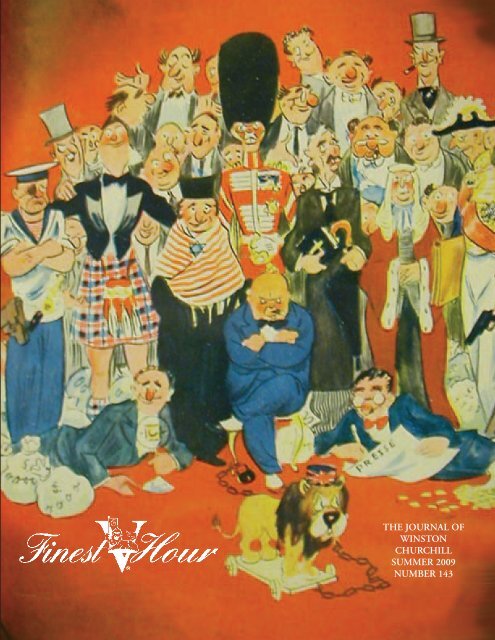

THE JOURNAL OFWINSTONCHURCHILLSUMMER 2009NUMBER 143

DESPATCH BOX3Number 143 • Summer 2009ISSN 0882-3715www.winstonchurchill.org____________________________Barbara F. Langworth, Publisherbarbarajol@gmail.comRichard M. Langworth CBE, Editorrlangworth@winstonchurchill.orgPost Office Box 740Moultonborough, NH 03254 USATel. (603) 253-8900Dec.-March Tel. (242) 335-0615___________________________Editor Emeritus:Ron Cynewulf RobbinsSenior Editors:Paul H. CourtenayJames W. MullerNews Editor:Michael RichardsContributorsAlfred James, AustraliaTerry Reardon, CanadaAntoine Capet, FranceInder Dan Ratnu, IndiaPaul Addison, <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>,James Lancaster,Sir Martin Gilbert CBE,Allen Packwood, United KingdomDavid Freeman, Ted Hutchinson,Warren F. Kimball, Justin D. LyonsMichael McMenamin,Robert Pilpel, Christopher Sterling,Manfred Weidhorn, United States___________________________• Address changes: Help us keep your copies coming!Please update your membership office whenyou move. All offices for The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centreand Allied national organizations are listed onthe inside front cover.__________________________________Finest Hour is made possible in part through thegenerous support of members of The <strong>Churchill</strong>Centre and Museum, the Number Ten Club,and an endowment created by the <strong>Churchill</strong>Centre Associates (page 2).___________________________________Published quarterly by The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre,offering subscriptions from the appropriateoffices on page 2. Permission to mail at nonprofitrates in USA granted by the UnitedStates Postal Service, Concord, NH, permitno. 1524. Copyright 2009. All rights reserved.Produced by Dragonwyck Publishing Inc.UNINTENDED RESULTSDavid Jablonsky’s “The <strong>Churchill</strong>Experience and the Bush Doctrine” (FH141) was a thoughful reminder of<strong>Churchill</strong>’s warning that war is full of unexpectedturns and unpleasant surprises.—JAMES MACK, FAIRFIELD, OHIODON CORLEONE VS.STAN AND OLLIEColonel Jablonsky’s piece on theuse of force in <strong>Churchill</strong>’s context asopposed to the “Bush Doctrine” is likecomparing “The Godfather” with “Laureland Hardy.” <strong>Churchill</strong> was a student ofthe use of the military to attain politicaladvantage. He never utilized a preemptiveattack such as Bush did on thegovernment of Iraq.Jablonsky makes a stretch to arguethat <strong>Churchill</strong> utilized a preemptiveattack on the Vichy fleet at Oran. At thisparticular time of World War II, GreatBritain was fighting for its very survival.Vichy France was a mere puppet state ofNazi Germany. Jablonsky states that theVichy was “nominally independent.” Hisargument is weak and superfluous.Jablonsky is correct in stating that<strong>Churchill</strong> expounded the virtues of militarypreparedness to make sure that theagreements of Versailles and Locarnowere followed. How these prescient activitiesby <strong>Churchill</strong> during his wildernessyears compare to anything PresidentBush advocated is beyond me.As stated in the author’s conclusion,<strong>Churchill</strong> would have taken greatercare in relations with Iraq. It was<strong>Churchill</strong>’s folly which created this dysfunctionalentity. He knew that whengoing to war, one must examine all theconsequences. <strong>Churchill</strong> was a soldierstatesman.In retrospect Bush was a manseeking statesmanship through warwithout the knowledge of a soldier.—RICHARD C. GESCHKE, BRISTOL, CONN.Editor’s response: Ordinarily Iwould ask the author to respond, butsince Col. Jablonsky is ill, I will reply forhim. To label something a “BushDoctrine” doesn’t necessarily mean oneapproves of it. It seems to me thatJablonsky’s piece, while sympathetictoward the former President’s dilemmas,was more critical than supportive: “theIraq war...has raised doubts not only inU.S. claims to legitimacy in its use ofFINEST HOUR 142 / 4force, but the efficacy of such efforts.” Tosay Vichy France was only “nominallyindependent” compared to Iraq is tostruggle asymptotically towards truth. InVichy France they had disagreement. Bycomparison Hussein’s Iraq was only“nominally independent,” and I’m nottoo sure it had a government, in the sensewe understand it. None of whichendorses or dismisses the Bush Doctrine.“<strong>Churchill</strong>’s folly” in Iraq (the titleof a recent book, which was not persuasive)is a judgment based on what weknow now. David Freeman (“<strong>Churchill</strong>and the Making of Modern Iraq,” FH132) explains that the factors governingWSC’s actions there ceased to applyalmost as soon as they were taken. Yet hisfolly kept Iraq stable for nearly fortyyears, even as his folly in Ireland kept thepeace for nearly fifty. Iraq today is lessscary than it was, but it asks too muchthat <strong>Churchill</strong> (or Bush) should be heldresponsible decades later, after the factorshave changed and others have had allthat time to repair or extend whateverfollies they committed.As <strong>Churchill</strong> said in 1952: “It isalways wise to look ahead, but difficult tolook farther than you can see.”★★★Your book, <strong>Churchill</strong> by Himself,praised by Mary Soames and MartinGilbert (FH 142: 53) sits tall and eclipseslesser compendiums. It reminds me of<strong>Churchill</strong>’s alleged reply to a taunt aboutIreland being only a small, weak country:“Yes, but it is a mother country.”I was twigged also by your contributionsto the pages of Finest Hour.Having just rifled through some backissues, I was struck by your meticulousnessand willingness, like <strong>Churchill</strong>, torecognize negatives while accentuatingpositives. Example: balanced treatment ofthe delicate issue of <strong>Churchill</strong>, Islam andrace (FH 114:45)—a subject that mightresurface over Kenya.My enthusiasm derives in partfrom having served as chairman of theorganization with the longest name, the<strong>Churchill</strong> Society for the Advancementof Parliamentary Democracy, and theprivilege of talking with some of thosewho were closest to the great man.ERNEST J. LITTLE, HAMILTON, ONT.Editor’s response: Mr. Little, meetMr. Geschke. Continued success to yourfine organization.✌

EDITOR’S ESSAY<strong>Churchill</strong> and Theodore RooseveltIs there a market for a symposium on <strong>Churchill</strong> and Theodore Roosevelt that would welcome both the<strong>Churchill</strong>ians and the “TR advocates” I know are among our readers? If you like the idea, email the editor.We have long been chary of joint conferences, which “gang aft agley.”At one such event recently <strong>Churchill</strong>ianspolitely turned out for all the non-<strong>Churchill</strong> panels; but the “other fellows” left as soon as their programs finished,or didn’t bother to attend at all. Perhaps we would have done the same had “they” hosted. The ideal approach wouldprobably be a symposium in some neutral corner, with a distinguished moderator and, to ice the cake, C-Span coverage.There’s more to the TR/<strong>Churchill</strong> relationship than seems apparent from its inauspicious beginnings. On hissecond visit to America in December 1900, <strong>Churchill</strong> met the Vice President-elect, who, as Robert Pilpel observed, “hadcharged up San Juan Hill two months before <strong>Churchill</strong> had charged at Omdurman. In their vitality, their energy, theirlust for adventure, the two men had other things in common as well. It was a case of likes repelling.” Roosevelt wrote: “Isaw the Englishman, <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> here....he is not an attractive fellow.”Six years later the President read Lord Randolph <strong>Churchill</strong>: “I dislike the father and I dislike the son, so I supposeI may be prejudiced....both possess or possessed such levity, lack of sobriety, lack of permanent principle, and an inordinatethirst for that cheap form of admiration which is given to notoriety, as to make them poor public servants.”The ice melted slightly in 1908, when, planning a safari to Africa, Roosevelt read <strong>Churchill</strong>’s My African Journey.“I do not like <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> but I supposed I ought to write him,” TR wrote U.S. Ambassador to Britain WhitelawReid. “Will you send him the enclosed letter if it is all right?” The letter thanked <strong>Churchill</strong> “for the beautiful copy ofyour book,” expressing the wish that “I shall have as good luck as you had.”Both Roosevelt and <strong>Churchill</strong> enjoyed a relationship with <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> the New Hampshire novelist. (See“That Other <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>,” FH 106.) TR often visited <strong>Churchill</strong> and others gathered around Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ literary colony in Plainfield, New Hampshire, not far from <strong>Churchill</strong>’s home in Cornish. Alistair Cooke,speaking at our 1988 Bretton Woods conference, began by saying he was pleased that so many had “come to the statewhere <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> spent the last forty years of his life.”“Why don’t you go into politics?” English <strong>Winston</strong> wrote the American, after they’d met on the same journey inwhich <strong>Churchill</strong> visited Roosevelt. “I mean to be Prime Minister of England: it would be a great lark if you werePresident of the United States at the same time.” American <strong>Winston</strong> was elected to the New Hampshire legislature (1903,1905), but rose no higher—in part because of TR. In 1912 Roosevelt broke with William Howard Taft and formed theProgressive or “Bull Moose” party, unsuccessfully opposing Taft for President. In the same election American <strong>Winston</strong>,also running as a “Bull Moose,” lost a bid for Congress. I suspect, but have not been able to prove, that the relationshipbetween the two <strong>Winston</strong>s withered because of TR’s influence: they could hardly been so close and not have discussedAmerican <strong>Winston</strong>’s opposite across the Atlantic.Roosevelt began to admire English <strong>Winston</strong> after World War I broke out in 1914, when he wrote a friend: “Ihave never liked <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>, but in view of what you tell me as to his admirable conduct and nerve in mobilizingthe fleet, I do wish that if it comes your way you will extend to him my congratulations on his action.”English <strong>Winston</strong> for his part seemed to harbor no hostility for TR—quite the contrary. Despite the BolshevikRevolution in 1917, <strong>Churchill</strong> typically remained committed to job #1: “beating the Hun.” As Martin Gilbert has stunninglyrevealed, <strong>Churchill</strong> actually proposed that Britain send what he called a “commissar” to Lenin, to negotiate Russia’sre-entry into the war—in exchange for which Britain would guarantee the Bolshevik revolution! When he realized that inno event would that commissar be he, <strong>Churchill</strong> recommended Theodore Roosevelt.Sir Martin tells me he sprang this remarkable factoid in Moscow, in a lecture before a large number of highrankingSoviet officers. “You could have heard a pin drop,” he said.Teddy Roosevelt had died when <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> next visited America in 1929, but he did find himselfseated at a dinner party with the President’s daughter, Alice Roosevelt Longworth. “Despite her lineage,” Robert Pilpelwrote, “Mrs. Longworth seems not only to have taken to him but even to have engaged in a little flirtation as well.When he asked her to state her opinions about Prohibition, for example, she leaned over and murmured, ‘I wouldrather whisper them to you.’ (Of course, this may simply have been because bad language from a lady was stillunacceptable in polite society.)”Pilpel’s judgment of “likes repelling” was confirmed by the late Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., after I published apiece on their relationship in Finest Hour 100. “I once asked Alice Roosevelt Longworth why her father disliked <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong> so much,” Schlesinger wrote. “She replied, ‘Because they were so much alike.’”✌FINEST HOUR 143 / 5

DATELINESWITH A FRIEND: 1951 General Election.BULLDOG NOTLONDON, JANUARY 12TH (REUTERS)—The classic English bulldog,symbol of defiance and pugnacity(though in fact a friendly andaffectionate animal) may now disappear.A shake-up of breedingstandards by the Kennel Club hassignalled the end of the dog’s<strong>Churchill</strong>ian jowl. Instead, the dog willhave a shrunken face, a sunken nose,longer legs and a leaner body. TheBritish Bulldog Breed Council is threateninglegal action against the KennelClub. Chairman Robin Searle said:“What you’ll get is a completely differentdog, not a British bulldog.”Finest Hour referred this one tolongtime colleague, prominent motoringwriter and bulldog partisan GrahamRobson, who writes:“As a long-time bulldog owner(your editor has met various of mymuch-loved mutts) I am at oncedelighted and appalled by what is beingproposed. Loud-mouthed critics of ‘traditional’bulldogs talk about breathingdifficulties (usually untrue), too-fatbodies (only some breeders encouragethis—mine never), heads too large andlegs too short (arguable—none of minewere ever grotesque), and difficulties indelivering puppies without a vet’s help(unfortunately true).“The KennelClub (for historicparallels think ofthe Gestapo orGeorge Orwell’s Thought Police) isdemanding changes to what is known asthe written standard for dogs—not justbulldogs, but other breeds too. They willeventually get their way, but it will takedecades of selective breeding to producea series (rather than an occasionalexample) of bulldogs to a ‘new’ standard.“I would be delighted to see bulldogswith somewhat longer legs, but stillwith the traditional look (including ‘flat’face and <strong>Churchill</strong>esque attitude), and awide-legged stance—like each of theseven generations of bulldog which myfamily has owned, and owns to this day.However, I would be appalled to seelonger noses, shrunken faces and leanbodies, since this means we will be goingback to the “Boxer” identity, destroyingthe most endearing characteristics of thetrue bulldog.“Anyone who doubts that my son’sfive-year-old bulldog cannot play, run, andenjoy himself in every way is welcome totry to wear him out before I do.”HMS Bulldog (H91), 1929-1946Since 1782, seven Royal Navyships have borne the name Bulldog. Thelast was a B-Class fleet destroyer laiddown on 10 August 1929. Early inWW2 she was deployed as an attendantto HMS Glorious and HMS Ark Royal.As part of the Home Fleet in a 1940action against E-boats, Bulldog towedLord Mountbatten’s badly damagedHMS Kelly to the Tyne for repairs. Afterdistinguished convoy duty through thewar, Bulldog was broken up at Rosyth in1946. She achieved the distinction ofbeing in operational service for most ofthe war apart from periods of refit orrepair. —www.navalhistory.netLAS PALMAS REMEMBERSLAS PALMAS, CANARY ISLANDS, MARCH26TH— <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> visited theCanary Islands three times* but theplaque being unveiled at the Port in LasPalmas in honour of one of GreatQuotation of the Seasonppeasement from weakness“Aand fear is alike futile andfatal. Appeasement from strength ismagnanimous and noble and mightbe the surest and perhaps the onlypath to world peace. When nations orindividuals get strong they are oftentruculent and bullying, but when theyare weak they become better mannered.But this is the reverse of whatis healthy and wise.”—WSC, HOUSE OF COMMONS,14 DECEMBER 1950Britain’s most internationally influentialfigures was to commemorate his visitfifty years ago. As a guest aboard theOnassis yacht Christina, he came to theisland for a holiday, and as a tourist,chose to visit Caldro de Bandama andMontaña de Arucas. In memory of hisvisit a plaque was unveiled by theMayor of Las Palmas, JerónimoSaavedra Acevedo.It has been written that GeneralFranco’s reluctance to risk losing theCanary Islands was the reason Spainnever officially entered into the war, as<strong>Churchill</strong> had warned that an invasionwas logistically possibile.A painting of <strong>Churchill</strong> hangs inthe British Club, where the fondlyremembered <strong>Churchill</strong> Restaurant waslocated. Matthew Vickers, chairman ofthe Club and his wife were present “torepresent the British community….It’sinteresting that here they respect himenough to unveil a plaque….He wassomeone who could see all of theenjoyment there was to see here….Hewas never one to shrink from challengesand there are lots of challengesfor everyone. He had that ‘never saydie’ spirit. Ultimately he was all abouthow you can build stronger linksbetween people.”The consensus among the guestsattending was that <strong>Churchill</strong> was aunique character who deserved beingremembered in the Canary Islands.Francisco Marin Loris, from the RealSociedad Economica de Amigos delPais de Gran Canaria, said it gives asense of pride to the Canarians that aman of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s stature chose toFINEST HOUR 143 / 6

holiday on Gran Canaria, and increasesthe interest of British visitors to learnmore about the history of the island.—DEBORAH WOODMANSEY(WWW.ROUNDTOWNNEWS.CO.UK)1959: Onassis, WSC, and Sgt. Murray onGran Canaria. (Editorial Prensa Canaria)*Editor’s note: The 1959 visit wason 26 February; see Gilbert, <strong>Winston</strong> S.<strong>Churchill</strong> VIII: 1284. I have verified the1961 visit, again via Christina, but notthe third. Can readers assist? RMLBRITAIN FORGETSLONDON, 25 MARCH 2009— Children willno longer study World War II andQueen Victoria, but instead learn how toassert themselves on the Internet underradical plans to overhaul primary schoolteaching. According to reports today, thenew draft curriculum commissioned bythe government claims that pupils can dowithout learning about the battle againstNazism and the rise and fall of theBritish Empire.In a move which will horrify manyparents, it would see children focus oninternet tools such as Wikipedia andpodcasting, as well as innovations such asblogging and Twitter, which allows usersto post instant minute-by-minuteupdates about their lives. How thissmacks of the “Me Generation.”Schools Minister Lord Adonis sayschildren will still have to learn about theSecond World War as part of secondaryschool curriculum, including <strong>Churchill</strong>’srole in defeating the Nazis. Cutting<strong>Churchill</strong> from history lessons, he toldSky News’ Sunday Live programme, is“completely wrong….It is a statutory andmandatory requirement of the new curriculumfor all students in secondaryschools in England to study the SecondWorld War. I cannot conceive how youcan teach the history of the SecondWorld without having <strong>Churchill</strong>, Hitlerand Stalin as part of the story.”—DAILY MAILGILBERT WINS BRADLEYWASHINGTON, JUNE 3RD— One of four2009 Bradley Prizes, each carrying astipend of $250,000, was presented toCC Honorary Member and Trustee SirMartin Gilbert at the John F. KennedyCenter for the Performing Arts.“The Bradley Foundation selectedSir Martin Gilbert for his compellingwork in historical research and his commitmentto freedom,” said FoundationPresident and CEO Michael W. Grebe.“Sir Martin’s seminal work in history hasbeen widely acclaimed, and his work isconsidered the standard in its field.”Sir Martin was knighted by QueenElizabeth II in 1995 for “services toBritish history and international relations,”and earlier named a Commanderof the Most Excellent Order of theBritish Empire (CBE). He is anHonorary Fellow at Merton College,Oxford, a Distinguished Fellow atHillsdale College, and the author ofseventy books, specializing in the twoWorld Wars, the Holocaust and scholarlyatlases in addition to <strong>Churchill</strong>.The selection was based on nominationssolicited from more than 100prominent individuals and chosen by acommittee including Terry Considine,Pierre S. du Pont, Martin Feldstein,Michael Grebe, Charles Krauthammer,Heather MacDonald, San W. Orr Jr.,Dianne J. Sehler and Shelby Steele.Founded in 1985, The Lynde andHarry Bradley Foundation is devoted tostrengthening American democratic capitalismand the institutions, principles andvalues that sustain and nurture it. Its programssupport limited government,dynamic economic and cultural activity,and a defense of U.S. ideals and institutions.Recognizing that self-governmentdepends on enlightened citizens, theFoundation supports scholarly studiesand academic achievement.BRITAIN REMEMBERSLONDON, MAY10TH— Withhis “Into theStorm” telefilmappearingin Americaand Britain,Irish actorBrendanGleeson’s portrayalofFINEST HOUR 143 / 7<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> drew raves. Thenotice that stands out most for him camethe other night at a screening in London,from <strong>Churchill</strong>’s daughter, 86-year-oldLady Soames.“I think she was genuinelypleased,” Gleeson reports. “She said Ididn’t fall into the usual traps or somethingof that nature. Of course for her itwas looking into the past. She said, ‘Thisis very emotional for me.’”The joint HBO-BBC production(reviewed on page 44) picks up where the2002 “The Gathering Storm” (FinestHour 115) left off, with the war yearsseen via flashbacks as <strong>Winston</strong> andClementine (Janet McTeer) awaitpostwar election results. “The GatheringStorm” won shelves of awards, includingEmmys for Outstanding Made for TVMovie and Outstanding Lead Actor forAlbert Finney—a fact of which Gleesonwas quite aware when he took on the job.Finney’s performance, he says, “had suchforce and humanity in it that you say,‘Where do you take it from there?’”Portraying the iconic figure “was ahuge acting challenge” which includedportraying someone twenty years olderthan himself. Gleeson admits, “I was alittle wary of it being a bridge too far, ofmiscasting myself, but the peopleinvolved were very encouraging.”— MARILYN BECK AND STACY JENEL SMITH,NATIONAL LEDGERGAMESMANSHIPAUGUSTA, GA., APRIL 7TH— It was 1957when Gary Player first pointed his cardown Magnolia Lane to the AugustaNational clubhouse—a place, he so oftenhas implied, where golfers “begin tochoke as you drive in the gates.”The Hall of Fame golfer did itagain today, commencing his fifty-secondweek at the Masters Tournament. Putanother way, he will have spent an entireyear of his life chasing golf balls aroundAugusta National by the match’s end.And that’s where Player has decided itshould conclude. The 73-year-old SouthAfrican announced Monday that thisMasters will be his last as a competitor,signing off on a tenure that began beforeeighty-nine of this week’s other ninetyfiveentrants were born. “I’ve had such awonderful career,” Player said. “Mygoodness, when I think of the career I’vehad—you can’t have it all, and I did haveit all. You can’t be greedy. <strong>Winston</strong> >>

DATELINESGARY PLAYER...<strong>Churchill</strong>, one of my all-time greatheroes, always said it’s never a bad thingto cry. It’s a cry of appreciation andenjoyment, a cry of gratitude.”FOR THEBIRDS:Giles Palmersays theswans aresettling innicely.—JEFF SHAIN, MIAMI HERALDBLACK SWANS RETURN“All the black swans are mating, not onlythe father and mother, but both brothersand both sisters have paired off. ThePtolemys always did this and Cleopatra wasthe result. At any rate I have not thought itmy duty to interfere.”—WSC TO HIS WIFE, CHARTWELL, 21JAN35WESTERHAM, KENT, MAY 26TH— Seventyfiveyears ago Lady Diana Cooper surveyedChartwell’s birds: “five foolish geese, fivefurious black swans, two ruddy sheldrakes,two white swans—Mr. Juno and Mrs.Jupiter, so called because they got the sexeswrong to begin with, two Canadian geese(‘Lord and Lady Beaverbrook’) and somemiscellaneous ducks.”Chartwell’s black swans have beenlooked after as zealously as the apes onGibraltar (Finest Hour 125:6), but overthe years marauding foxes and minkreduced the population, which reachedzero last year. Happily last winter,Chartwell head gardener Giles Palmerinstalled a new floating “swan island” toprovide natural protection, and two newblack swans (Cygnus atratus) are nowcruising the ponds designed by Sir<strong>Winston</strong> himself.Mr. Palmer told Kent News(www.kentnews.co.uk): “I have seen theswans on their island once or twice butam confident that they will see just whatthey are missing out on as soon as thefoliage on the island grows up. For now,I’m simply thrilled that the swans are settlingon so well and getting to know thegardens. They’re getting so brave nowthat they ventured all the way to thekitchen garden recently.” The floatingisland has allowed gardeners to removeugly mesh screening set up against predators,returning the lakes to theirappearance in <strong>Churchill</strong>’s time. (We hopethey’re right about this.)The first black swans were a giftfrom Sir Phillip Sassoon in 1927. Thepopulation was topped up by the governmentof Western Australia, where theblack swan is a state symbol. C. atratus isnative also to Tasmania and has beenintroduced to New Zealand. It is theworld’s only black swan, though its flightfeathers, invisible at rest, are white. GilesPalmer hopes the pair will soon breedand begin a new generation.<strong>Churchill</strong> was devoted to his swansand regularly conversed with them in“swan talk,” in which he claimed proficiency.But a former bodyguard, RonaldGolding, wrote (see page 31) that thiswas one of WSC’s little myths, becausethe swans would cry out to anyone whoapproached within a certain distance:“It was some time after this discoverythat I was walking down to thelake with Mr. <strong>Churchill</strong>. I was a little infront, and watched carefully for the criticalspot. I then called out in ‘swan-talk’and the birds dutifully replied. Mr.<strong>Churchill</strong> stopped dead. I turned roundand he looked me full in the eye for amoment or two. Then the faintest suspicionof a smile appeared and he walkedon in silence. No comment was evermade that this secret was shared.”FH TRAVEL GUIDELONDON, APRIL 1ST— On England’s“<strong>Churchill</strong> Trail,” Carol Ferguson of theHerald-Banner, Greenville, Texas, stoppedto chatwith twogents on abench onNew BondStreet. “I’mpromptedto thankFinest Hour for its regular travel tips,”Carol writes, “especially the addresses of<strong>Churchill</strong>’s London homes and directionsto Chartwell. My daughter and I scoutedthem out together.”GETTING TO CHARTWELLPERIODIC ADVISORY— Chartwell is openWednesdays through Sundays fromMarch through 1 November from 11amto 4pm, and on Tuesdays in July andAugust. Local telephone: (01732)863087. We like to remind readers ofhow to get there from London.By car: the drive nowadays is notsomething for the faint-hearted or trafficchallenged,or North Americans notfamiliar with righthand-drive. Chartwellis two miles south of Westerham on theA25, accessed by M25 junctions 5 or 6.Drive to the town centre, take the B2026a few miles to the car park (on left).By bus: Sevenoaks station 6 1/2miles; Oxted station 5 1/2 miles;Metrobus 246 from Bromley station toEdenbridge passes the gates. TheNational Trust’s Chartwell Explorercoach takes visitors from Sevenoaks toChartwell for £3, which provides unlimitedbus travel to any local Trust propertyand a pot of tea at Chartwell. You canalso get a combined ticket from London,which includes train and coach, for £13,or £8.50 for Trust members. Details at(08457) 696996.By rail: Some recommend CharingCross Station to Sevenoaks (four fasttrains per hour). Others suggest VictoriaStation (fewer trains, but some marked“to East Grinstead and calling atOxted”). Though only a mile closer thanSevenoaks, Oxted is less congested,making for a lower taxi fare. Arrange tohave the cabbie pick you up for yourreturn from Chartwell, so you don’t getstranded—although there are worseplaces to be stranded than Westerham.There’s a lovely footpath from Chartwellto the town, with its famous King’s Armspub. (Factoid: the Nemon statue of<strong>Churchill</strong> on the village green was a giftfrom the people of Yugoslavia.)CHERIE REVEALS ALLLONDON, MAY 5TH— The wife of formerBritish PrimeMinister TonyBlair compares herspouse to WSC.Cherie Blair toldVanity Fair thather husband “wasfantastic. I’m surehistory will judgehim very well. Ithink he’ll be upthere with <strong>Churchill</strong>.” But, she was lesscomplimentary about her own image:“Just looking at the press cuttings, youcould not say that it was a triumph,could you!” Cherie has admitted that herhusband was taken aback a little by someDRAWING BY KARL MEERSMANFINEST HOUR 143 / 8

of the saucy contents in her new memoir,Speaking for Myself: “I think he’s ratherembarrassed by the love affair bits. Idon’t think he particularly read thoseclosely. Been there, done that!”Yes, well... At least Cherie didn’tliken herself to Clementine <strong>Churchill</strong>.“THE SEASHORE”LONDON, MAY 21ST— <strong>Churchill</strong>’s “TheSeashore” (Coombs 320) was placed onauction at Christie’s today, estimated at£200,000-300,000. The sale benefittedthe Queen’s Silver Jubilee Trust.The provenance is WilliamGreenshields, <strong>Churchill</strong>’s butler between1948 and 1953. “The Seashore” wasgiven to him by <strong>Churchill</strong>, as well as afurther work called “Antibes,” which soldat Sotheby’s in 1966.According to David Coombs, thepreeminent expert and co-author withMinnie <strong>Churchill</strong> of Sir <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong>: His Life through His Paintings,the scene is one of a series that <strong>Churchill</strong>painted during the 1930s, in which hedemonstrates his fascination with the seabreaking on the shore. The exact locationis not known, but these coastal scenesappear to be painted from the FrenchRiviera.Since 1977, The Queen’s SilverJubilee Trust has supported charities thatwork with young people in the UK,Channel Islands, Isle of Man and theCommonwealth. Through its grantmakingactivity, the Trust has helpedhundreds of thousands of young peopleto find employment, volunteer in theirlocal communities or experience newopportunities that they would not otherwisehave enjoyed.PUBLIC INTELLIGENCEWASHINGTON, APRIL 30TH— R. EmmettTyrell, Jr., editor of The AmericanSpectator, comments on the recent debateAROUND & ABOUTThe Things They Say Department: the Wall StreetJournal, April 24th, reports: “In London, [PresidentObama] said that decisions about the world financialsystem were no longer made by ‘just Roosevelt and <strong>Churchill</strong>sitting in a room with a brandy’—as if that were a bad thing.” Maybe not, butit’s a simplification of wartime decision-making. Also, FDR drank vermouthlacedmartinis, which <strong>Churchill</strong> reportedly dumped in the nearest flower pot.Thanks to Elliot Berke for this snippet.❋❋❋❋❋How the Mighty Have Fallen Bureau: “When Prime Minister GordonBrown came a-calling at the White House, there was no trip to CampDavid, no state dinner or joint meeting with the press, and nobodyquoting <strong>Churchill</strong> that we noticed. An aide explained to the UK’s SundayTelegraph: “There’s nothing special about Britain. You’re just the same asthe other 190 countries in the world. You shouldn’t expect special treatment.”One editorial suggested the UK threaten to set off one of itsnuclear weapons: “That might get their attention.”❋❋❋❋❋Last issue we presented the Finest Hour Re-Rat Award to SenatorJudd Gregg (R.-NH), who accepted nomination as President Obama’sSecretary of Commerce but then withdrew. (<strong>Churchill</strong>, who deserted theConservatives for the Liberals in 1904 but oozed back to the Tories in1925, later said, “Anyone can rat, but it takes a certain amount of ingenuityto re-rat.”) Re-ratting, a lost art, is experiencing a revival. Just a fewweeks later, Senator Arlen Specter (D.-Pa.) re-ratted by switching fromthe Republicans to the Democrats. A registered Democrat, Specter beatPhiladelphia Democrat District Attorney James Crumlish in 1965,and subsequently changed his registration to Republican.We must now commission twocopies of the Re-Rat Award, which we thinkmight take the shape of the “Flying Fickle Fingerof Fate” once dispensed by the Rowan andMartin TV show “Laugh-In.” Re-ratting, if itspreads, could produce a historic realignment,perhaps even new Liberal and ConservativeParties, which would better define the two oppositeapproaches to issues of the day. Then wecould get down to the business of arguing outthe debate, instead of obfuscating, dodging and weaving in order to toesome known or imagined party line. As <strong>Churchill</strong>, who always put principlebefore party, remarked early in 1907: “The alternation of Parties inpower, like the rotation of crops, has beneficial results.”over declassifying top secret documents:“…frankly I am uneasy about this newclimate here in Washington. Historically,intelligence documents have been keptfrom public eye, not just here butthroughout the Western world. The ideais that we do not want our enemies to beinformed of what we know. DavidReynolds’ In Command of History, onhow <strong>Churchill</strong> wrote his World War IImemoirs, repeatedly shows <strong>Churchill</strong> andhis opponents in the Labour governmentcooperating to keep secrets from thepublic. British intelligence techniqueswere not divulged….Intelligence officerswithin our service have been intimidatedby our own government. Foreign intelligenceofficers who have been sharingintelligence with us abroad are going tobe much less forthcoming.” >>FINEST HOUR 143 / 9

125-100-75-50 YEARS AGO125 years agoSpring, 1884 • Age 9“He has no ambition”At the end of the summer term,<strong>Winston</strong>’s parents removed himfrom St. George’s School in partbecause his nanny, Mrs. Everest, saw evidenceof the canings <strong>Winston</strong> hadreceived at the hands of the school’ssadistic Headmaster, Sneyd-Kynnersley,whose assessment of the young man onJune 20th was that “He has no ambition.”His final report on July 21grudginglyadmitted: “Hemight always dowell if he chose,”noting that<strong>Winston</strong>’s diligencewas “fairon the whole,”but that he still“occasionallygives a great dealof trouble.” It ismore than likelythat <strong>Winston</strong> washappiest at St.George’s Schoolwhile he wasgiving theHeadmaster “agreat deal of trouble.”Lord Randolph and the FourthParty were once more at odds with theirleaders in the Conservative Party whowere seeking to amend the Reform Billon voter eligibility to exclude Ireland.During his formative years, <strong>Winston</strong> readand re-read all of his father’s speeches.The following excerpt from LordRandolph’s biting comments on thesubject illustrates that, as a speaker,<strong>Winston</strong>’s acorn did not fall far from hisfather’s oak:The Tories had argued that no votesshould be given to Irish peasantsbecause they lived in “mud cabins.”Lord Randolph replied: “I have heard agreat deal of the mud-cabin argument.For that we are indebted to the brilliant,ingenious and fertile mind of theRt. Hon. Member for Westminster. Isuppose that in the minds of the lordsof suburban villas, of the owners ofvineries and pineries, the mud cabinrepresents the climax of physical andsocial degradation. But the franchise inEngland has never been determined byParliament with respect to the characterof the dwellings. The differencebetween the cabin of the Irish peasantand the cottage of the English agriculturallabourer is not so great as thatwhich exists between the abode of theRt. Hon. Member for Westminster andthe humble roof which shelters fromthe storm the individual who now hasthe honour to address the Committee.”<strong>Winston</strong> later noted in his biographyof his father that “cheers andlaughter” had greeted Lord Randolph’scomment100 years agoSummer, 1909 • Age 34“It was a great coup”<strong>Churchill</strong> became a father for thesecond time on July 11th withthe birth of his daughter Diana,whom he nicknamed “the cream-goldkitten.” Three weeks later, <strong>Churchill</strong>’spersonal intervention in the coal miners’strike produced a satisfactory resolution,as he wrote his mother on 4 August:I had a great triumph….We had 20hours negotiations in the last two daysand I do not think a satisfactory resultwould have been obtained unless I hadpersonally played my part effectually. Ihad a nice telegram from the King, andletters from Asquith and Grey all veryeulogistic. It was a great coup, mostuseful and timely.Prime Minister Asquith may havebeen eulogistic over <strong>Churchill</strong>’s settling ofthe strike, but the same was not true ofWSC’s recent speech in Edinburgh inJuly, where <strong>Churchill</strong> had criticized theHouse of Lords for threatening to rejectLloyd George’s “People’s Budget”—whichincluded, among other things, a 20percent tax on increased land values.<strong>Churchill</strong> wrote defending himself,enclosing a speech he had given inBirmingham in January with whichAsquith had expressed satisfaction.“Nothing in my speech in Edinburghgoes beyond this. Indeed it seems to meto be a mere restatement.” <strong>Churchill</strong>wrote, quoting this excerpt from theBirmingham speech:I do not, ofcourse, ignorethe fact thatthe House ofLords has thepower, thoughnot, I think,the constitutionalright, tobring the governmentof thecountry to astandstill….Ifthey reallybelieve, as theyso loudly proclaim,that thecountry willhail them as itssaviours, theycan put it tothe proof….And, for my part, I shouldbe quite content to see the battlejoined as speedily as possible [cheers],upon the plain simple issue of aristocraticrule against representativegovernment [cheers], between thereversion to protection and the maintenanceof free trade [cheers], between atax on bread and a tax on—well, nevermind. [Cheers and laughter.]by Michael McMenamin75 years agoSummer, 1934 • Age 59“First requisite of peace”On June 30th <strong>Churchill</strong>’s firstcousin, “Sunny,” the NinthDuke of Marlborough, died.<strong>Churchill</strong> wrote of him in a subsequentletter to The Times as my “oldest anddearest friend.” By a gruesome coincidenceSunny died on the same day as thetrue face of National Socialism wasrevealed in Germany during the “Nightof the Long Knives,” when Hitlerordered the wholesale slaughter of hisFINEST HOUR 143 / 12

political adversaries, including ErnstRöhm, head of the SA, and all of his toplieutenants.Even political retirement did notspare those who had incurred Hitler’senmity, including the Nazi Party’s formernumber two man, Gregor Strasser—orHitler’s predecessor as Chancellor,General Kurt von Schleicher, who, alongwith his wife, was murdered by no fewerthen six gunmen from Himmler’s SS.Hitler biographer Ian Kershaw estimatesthe death toll at between 150 and 200.Sunny’s death deeply affected<strong>Churchill</strong> and may explain why, in thedays that followed, <strong>Churchill</strong> did notexplicitly condemn Hitler’s cold-bloodedkilling of his political enemies. But, in along article in The Daily Mail on 9 July,<strong>Churchill</strong> left no doubt about the implicationsfor the future peace of Europe.No one else in England or anywhere elsefor that matter had by that time so succinctlysummarized what Germany hadbecome under National Socialism:1928: Hitler and Goering (lower left, medalsdecorating his ample bosom) with the SA ata Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg. (Wikimedia)nation, seventy millions of the mostindustrious, valiant, gifted people inthe world, in the hands of a smallgroup of fierce men.When shall we learn that Britain’s hourof weakness is Europe’s hour of danger?When shall we comprehend that for sogreat and wealthy a power with suchrich possessions to remain in a positionwhere it can be blackmailed is tocommit an offence against the cause ofpeace?Surely at the very least we ought to putourselves in as good a position as wewere before the Great War. Then, wewere at any rate under the shield of theNavy. We could enter or stand outsideContinental struggles as we pleased. Thefirst requisite of peace is that Britainshould be capable of self-defence.In England’s balmy summer of 1934, fewwere listening.50 years agoSummer, 1959 • Age 84“The greatest Englishman”In July, 1959, <strong>Churchill</strong> was cruisingnear Greece and Turkey aboardAristotle Onassis’ yacht Christina,accompanied by, among others, hisphysician Lord Moran, AnthonyMontague Browne and his wife, andOnassis’ mistress, the opera singer MariaCallas. During the tour, Sir <strong>Winston</strong> metboth the Turkish and Greek PrimeMinisters.Later that summer, <strong>Churchill</strong> wasinvited by President Eisenhower to meethim during his state visit to London.They were together at two dinners on 31August and 1 September.Earlier, in the South of France,<strong>Churchill</strong> invited the Israeli PrimeMinister, David Ben-Gurion, to lunchafter learning that Ben-Gurion was alsoin France. Unfortunately, by the time theinvitation arrived, Ben-Gurion’s ship hadalready departed for Israel. Ben-Gurionwrote to <strong>Churchill</strong>:I need hardly assure you that I shouldhave been delighted to accept the invitation,if only it had found me still inFrance. Like many others in all parts ofthe globe, I regard you as the greatestEnglishman in your country’s historyand the greatest statesman of our time,as the man whose courage, wisdom andforesight saved his country and the freeworld from Nazi servitude [as well as]one of the few men in the free world torealize the true character of theBolshevik regime and its leaders. ✌29 MAY 1958: Sarah <strong>Churchill</strong> and PrimeMinister Ben-Gurion unveiling the plaquein the <strong>Churchill</strong> Auditorium, Mt. Carmelcampus of the Technion, Israel Instituteof Technology. (Wikimedia Commons)That mighty race who fought andalmost vanquished the whole world ison the march again. The whole nationis inspired with the idea of retrievingand avenging their defeat in the GreatWar. They have arisen from the pit ofdisaster in a monstrous guise: hatredinternal and external, organized as if itwere a science; debts repudiated to buythe means of making cannon; treatiesbroken to construct a gigantic AirForce; schools placarded with maps ofterritories to be regained; allParliamentary safeguards, all internalcriticism trampled down; evenChristianity itself conscripted to atribal purpose; the whole GermanFINEST HOUR 143 / 13

COVER STORY<strong>Churchill</strong> inNazi CartoonPropagandaRANDALL BYTWERK“I ALWAYS LOVED CARTOONS,” CHURCHILLWROTE IN 1931. IT WOULD HAVE BEEN ASK-ING A LOT FOR HIM TO LOVE THE ONES THEGERMANS GENERATED A FEW YEARSLATER: A GRAPHIC REMINDER OF WHAT HEWAS UP AGAINST.Above: DieBrennessel (The StingingNettle) #54, 18 December 1934: The first known<strong>Churchill</strong> cover in the Nazi press, following his earliestwarnings on Germany’s rearmament. The captionreads: “<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> juggles figures on ‘German aircraft’:‘Toss me another zero—it won't make muchof a difference.’”<strong>Churchill</strong>’s attacks on the Nazis are masterpieces ofinvective, and the Nazis returned fire. To JosephGoebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda, he was“the biggest and most experienced liar in modern history,”and that was one of Goebbels’ gentler attacks. In Hitler’sspeeches WSC was “whisky-besotted,” and he was oftenportrayed in Nazi cartoons with a drunk’s red nose.<strong>Churchill</strong>’s place in Nazi propaganda varied directlywith his threat level. At first he was a minor target, an irrationalEnglishman pushing for needless war with Germany.Between May 1940 and the invasion of Russia, he was themain enemy, the drunken demagogue at the head of Britishplutocracy who stood in the way of Germany’s desire for ajust world order. After June 1941, he was the puppet ofRoosevelt and Stalin, and the Jews who controlled themfrom behind the scenes: a character of the past who wouldruin England in a vain attempt to defeat Germany. ButGoebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister, came to have agrudging respect for <strong>Churchill</strong>’s ability as a propagandist.Die Brennessel #46, 15November 1938: Eden and <strong>Churchill</strong>, thewarmongers after Munich, sitting at the feet of Mars.Dr. Bytwerk is Professor of Communication at Calvin College in GrandRapids, Michigan, and author of Julius Streicher and Bending Spines:The Propagandas of National Socialism and the German DemocraticRepublic. In his Landmark Speeches of National Socialism (2008) hewrites: “The Germans claimed that they did not know what was happening—thatwas not persuasive. Everything that Nazism intendedwas revealed in its rhetoric. He who had ears could have heard.”FINEST HOUR 143 / 14

Early on, <strong>Churchill</strong> received attention only when hemade the news. A December 1934 cartoon in Brennessel,the Nazi Party’s humor weekly, had him juggling false statisticson German aircraft production. Four years later,Brennessel showed Eden and <strong>Churchill</strong> sitting at the feet ofMars, who approves of their opposition to Chamberlain’sappeasement policy at Munich. 1With the outbreak of war and <strong>Churchill</strong>’s return tothe Cabinet, he became a central figure. Nazi speakers weretold to say that he was now an “untiring warmonger,” thechief English opponent of peace with Germany. 2Through May 1940, as First Lord of the Admiralty,<strong>Churchill</strong> was presented as the bumbling victim of Germanmilitary brilliance. A January 1940 cartoon had himknocked over by a boxing ball. In April, he was shownbehind bars looking hungrily at a well-stocked table, thevictim of the U-boat blockade (back cover). Goebbels atthat time did not think much of him, commenting in hisdiaries that <strong>Churchill</strong> was energetic, but rash. 3Once <strong>Churchill</strong> became prime minister, he was thepersonification of evil for the year when Britain stood aloneagainst Germany. In July 1940, Goebbels ordered Nazi propagandists“to attack only <strong>Churchill</strong> and his clique ofplutocrats but never the British nation as such. <strong>Churchill</strong>himself had burnt all bridges behind him so that there canbe no question of any arrangement with Britain so long ashe is at the helm.” 4In caricatures, <strong>Churchill</strong> was now less a clown than acriminal, a big-mouthed blowhard with nothing to back uphis words. A 1940 cartoon showed a sweating <strong>Churchill</strong>awaiting the gallows, looking at a list ofbombed cities. >>The humor weekly LustigeBlätter (Funny <strong>Page</strong>s) was a relentless foe.Above: WSC smashed by the New World Order, 26 January1940. Below: Awaiting the Deutschland knife (following previouslydefeated foes Schusschnigg, Beneš, Chamberlain,Daladier, Reynaud and others), 19 July 1940. Left: Facing thenoose, the condemned prisoner with a list of British citiesbombed in the Blitz, January 1941.FINEST HOUR 143 / 15

Above,Lustige Blätter, 25 October1940: Hitler had postponed Operation SeaLion, but <strong>Churchill</strong> was now being led around theworld by Ahasver, the legendary "Wandering Jew."PROPAGANDA CARTOONS...A few months later, he was being led around the world by aJew—part of the message that as evil as <strong>Churchill</strong> was, hewas only a servant of the Jews, an argument that becamemore pronounced after 1941.As the Blitz mounted, <strong>Churchill</strong> was the madmanwho had brought ruin to England (as the Nazis alwayscalled Britain). A cartoon in November 1940 showed<strong>Churchill</strong> the “madman” watching from a window asLondon burned. (The Nazis didn’t realize his preferredperch was the Air Ministry roof.)Goebbels turned up his wrath as Britain failed tobuckle. His weekly columns in Das Reich, a widely circulatedprestige weekly, increasingly attacked <strong>Churchill</strong>. InJanuary 1941, he accused WSC of the Big Lie: “The astonishingthing is that Mr. <strong>Churchill</strong>, a genuine John Bull,holds to his lies, and in fact repeats them until he himselfbelieves them.” 5 A month later, <strong>Churchill</strong> was “the firstviolin in the hellish concert that the whole demo-plutocraticworld is playing against the Axis powers.” 6Goebbels mocked <strong>Churchill</strong>’s claim that all he couldoffer was “blood, toil, tears and sweat.” It was clever propaganda,he asserted. After all, if things got bad, one couldclaim to have predicted it, and if things got better, onecould take the credit. A cartoon soon made the point: theBritish lion was ill after drinking <strong>Churchill</strong>’s cocktail of“blood, sweat and tears.”Perhaps when the war is over, Goebbels speculated,<strong>Churchill</strong> would be forced to read aloud all of his speechesBelow, Der Stürmer (The Attacker), February 1940:“<strong>Churchill</strong>, the Braggart. The ruler of all the seas weepsmany a bitter tear. The poor man can hardly grasp it, thatthis is the end to the dream of ‘the supremacyof the seas.’”Above, Illustrierter Beobachter (IllustratedObserver) #25, June 1941: The Nazis picked up on WSC’s habit ofdictating from his bath: "Take this down: In my current situation, Ifear German U-boats even less than before."FINEST HOUR 143 / 16

in public. “He would then enjoy the most original death amortal ever had: he would drown in the world’s laughter.” 7Goebbels later wrote: “We can only be thankful that wehave <strong>Churchill</strong>. One may not wish he were not there. Oneshould take good care of him, because he is the trailblazerfor our complete and radical victory.” 8Nazi propaganda suggested that <strong>Churchill</strong> was fallingunder Americancontrol to get themoney he needed tocontinue the war. A1941 cartoon hadhim hauling Englandinto a Jewish pawnshop.Not onlywould <strong>Churchill</strong>lose the war—hewould sell theEmpire to theAmericans in theprocess. >>Left, IllustrierterBeobachter,March 1941,reprinted froman Italiannewspaper:“<strong>Churchill</strong>'slast speech, from thefront of the façade.” The façade looks alot like Buckingham Palace; at any rate, the Royal Armsare over the door.Left, Simplicissimus,22 October1939. “Zircus<strong>Churchill</strong>”approachingthe MaginotLine, with theGallic cock andNevilleChamberlain asthe British lion.WSC: “You jumpthrough thehoop first, dearcock, I shallfollow after.” Aswe nowknow,nobodythought ofjumpingthrough.Left, LustigeBlätter, 15November1940. WSClooks out hiswindow onthe fires ofLondon:“The philosophyof amadman:‘Our Empireis so largethat it hardlymakes a differenceif asmall islandburns.’”Below,LustigeBlätter,14February1941.<strong>Churchill</strong>and theKing haul“England”(as theGermansalwaysreferred toBritain) to aJewish pawnshop.Thecanny artisteven pickedup theirsmokinghabits.Left, LustigeBlätter, 23 April1942: the Britishlion after a<strong>Churchill</strong> cocktailof blood, sweat andtears. About thetime this cartoonwas published,JosephGoebbels told hiscolleagues how<strong>Churchill</strong>'s famouspromise wouldwork: If things gotworse, he could saythat's just what hehad predicted; ifthings got better,he could take thecredit.FINEST HOUR 143 / 17

Above: Simplicissimus #14,April 1944: Two months before D-Day,Roosevelt and <strong>Churchill</strong> are entwined by Stalin: “How neatlyyou have gotten caught in my web. Now all I need to do iswrap you up!” (www.simplicissimus.com)Der Stürmer, 13 February 1941: “Why does Britain wage thiswar? <strong>Churchill</strong> dares not make a reply. He remains dumb. Weknow quite well why one avoids giving a straight answer tothese questions—we, however, need not make a secret of theaim for which we strive, we fight for a free German life!”Above, Der Stürmer, #6, February 1943: “In the name ofHumanity.” High Priest Roosevelt: “The staff has broken, toomuch of her spoken.” Stalin wields the axe. As the tideturned and the Allies began to push German armies evercloser to the Reich, the theme became “Jewish Bolshevism.”PROPAGANDA CARTOONS...Following the invasion of Russia and the turningaside of the German onslaught on Britain, the full force ofNazi propaganda focused on Bolshevism and the Jews.<strong>Churchill</strong> now became a secondary figure. Just after theGerman defeat at Stalingrad, Goebbels launched a majorcampaign against Jewish Bolshevism. <strong>Churchill</strong> andRoosevelt were “to be presented as accomplices and toadiesof Bolshevism…which is the most radical expression of theJewish drive for world domination.” 9 This theme dominatedNazi propaganda for the remainder of the war.<strong>Churchill</strong> nevertheless remained a villain. In August1944, a cartoon titled “<strong>Churchill</strong>’s Debts” showed himlooking at the list of European cities Britain had bombed,an interesting comparison to the earlier cartoon in whichhe was held responsible for bombed English cities. A late1944 mass pamphlet quoted his famous words from 1941:“Nothing is more certain than that every trace of Hitler’sfootsteps, every stain of his infected and corroding fingers,will be sponged and purged and if necessary blasted, fromthe surface of the earth.” 10 This was cited as evidence that<strong>Churchill</strong>, like his master Stalin, intended to wipe outGermany and its people.In private, however, Goebbels gradually came to haverespect for <strong>Churchill</strong>’s abilities. In December 1941, he toldhis associates that <strong>Churchill</strong>’s strategy of promising only”blood, sweat and tears” had been correct. 11 And as the warsituation turned, he increasingly followed <strong>Churchill</strong>’sexample of admitting difficulties while confidently predictingfinal victory. <strong>Churchill</strong>, however, turned out to bethe more accurate prophet.FINEST HOUR 143 / 18

Left, DerStürmer,September1943:“Plutocrats’Domination:The Master’sChair.<strong>Churchill</strong> isannoyed atthe decorationon the throne.”Right,Simplicissimus,21 May 1941,after the Britishdebacle inGreece, a potsherdfrom aGrecian urnshows <strong>Churchill</strong>the “strategicgenius” runningaway two-faced,crying, “Help” and“Victory.”Simplicissimus,shut down in September 1944, along with many other German magazinesand party organs, owing to the consequences of what had now become totalwar. It was revived in 1954-67.Below: Lustige Blätter, #33, 18 August 1944, one of its last issues:“<strong>Churchill</strong>’s Debts.” In an interesting contrast with the 1941 cartoon of <strong>Churchill</strong> with a list of ruined British cities (page 15), anarm marked “V1” forces WSC to look at the cities and cultural treasures of Europe destroyed by British bombs.It is an enlightening fact that <strong>Churchill</strong> was indeed saddened by the destruction of the war—asentiment expressed by no other leader on either side.Endnotes1. For a wide range of Nazi propaganda on <strong>Churchill</strong>,see the German Propaganda Archive (GPA)http://bytwerk.com/gpa/winstonchurchill.htm. See alsoFred Urquhart, W.S.C.: A Cartoon Biography (London:Cassell, 1955), which contains about a dozen Nazi cartoonson <strong>Churchill</strong>.2. A translation is available on the GPA:http://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/rim1.htm.3. Georg Reuth, Joseph Goebbels Tagebücher 1924-1945 (Munich: Piper, 1999), 1373.4. Willi A. Boelcke, The Secret Conferences of Dr.Goebbels (New York: Dutton, 1970), 64-65.5. Joseph Goebbels, Die Zeit ohne Beispiel (Munich:Eher Verlag, 1941), 364.6. Ibid., 381.7. Ibid., 395.8. Joseph Goebbels, Das eherne Herz (Munich: EherVerlag, 1943), 218.9. The document is translated on the GPA:http://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/bolshevist.htm.10. Heinrich Goitsch, Niemals! (Munich: Eher Verlag,1944). A translation is available on the GPA:http://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/niemals.htm.11. Boelcke, 192. ✌FINEST HOUR 143 / 19

Top Cop in aTop HatCHURCHILL AS HOME SECRETARY14 FEBRUARY 1910 - 25 OCTOBER 1911RICHARD A. DEVINEThe traditional image of <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> is that ofthe courageous wartime Prime Minister, or the lonelyvoice in the 1930s warning about Nazi Germany, orperhaps that of the twice-First Lord of theAdmiralty. Few think of <strong>Churchill</strong> in the role of lawenforcer, but for approximately twenty months in 1910 and1911 that’s essentially what he was.Roy Jenkins described the Home Office as “a plank ofwood out of which all other domestic departments have beencarved. Ministries like Agriculture, Environment andEmployment have left big holes in the coverage of the HomeOffice. Apart from its central responsibility for police,prisons and the state of the criminal law it also retains a pile ofsemi-archaic responsibilities, often merely for the reason that noone has thought it worth while to put in a bid for yet anotheritem....” 1<strong>Churchill</strong> was appointed Home Secretary when he was 35: theyoungest person other than Robert Peel to hold the position. Thethen-wide ranging office made him a police superintendent, the headof prisons, a key decision-maker on clemency and commutation questions,and the head of probation services, to name a few of his duties.He was the “Top Cop” and more.The Home Office then had responsibility for the regulation ofworking conditions and administration of workmen’s compensation,but then, as now, public safety issues made the headlines: By the time hisservice as Home Secretary was over, <strong>Churchill</strong> had been assailed bystriking workers, attacked by women suffragists, challenged by decisionson capital punishment, and blamed for the fiery and dramatic deaths ofanarchist robbers. As with most of his life, when <strong>Winston</strong> was around,things were far from dull._______________________________________________________________________Mr. Devine is a member of the Chicago law firm of Meckler Bulger Tilson Marick andPearson. He served as State’s Attorney of Cook County, Illinois from 1996 to 2008. Thisarticle is based on his remarks to Churchllians of Chicagoland. In its preparation theauthor gratefully acknowledges the advice and assistance of Linnet Myers.Budget Day,27 April 1910FINEST HOUR 143 / 20

Though <strong>Churchill</strong> had little background in lawenforcement, he was a man of ideas who never hesitatedto express them at length and with vigor. The PermanentUnder-Secretary for the Home Office, Sir Edward Troup,captured a glimpse of his chief which prefigured the commentsof <strong>Churchill</strong>’s generals in World War II:Once a week or oftener, Mr. <strong>Churchill</strong> came into theoffice bringing with him some adventurous or impossibleprojects; but after half an hour’s discussion somethingevolved which was still adventurous, but not impossible. 2Strikes and StrikersGiven <strong>Churchill</strong>’s irrepressible nature, it is not surprisingthat he was a major player in significant events.There was a good deal of labor unrest, and in May 1910,a dispute erupted at the Newport docks. Feelings ranhigh. One of the employers, F.H. Houlder, said approvinglythat in Argentina they would send in “artillery andmachine guns” to handle the matter properly. 3To help maintain order local officials requested thatthe Home Office agree to the dispatch of both troops andadditional police. <strong>Churchill</strong> agreed to provide 250 footand fifty mounted policemen. Troops were kept in readinessnearby, but Permanent Under-Secretary Troupnotified the War Office that <strong>Churchill</strong> was “most anxious”that the military not be used. 4Neither police nor troops were needed. The Mayorof Newport telegraphed the Home Office on 22 May thatthe dispute had been settled by negotiations. Even thoughlaw enforcement was largely in the background, it wasgenerally agreed that the Home Office had played aresponsible role in resolving the Newport labor dispute. 5In November, 1910, there was a major dispute inthe Rhondda Valley, Wales concerning different pay scalesfor miners, about 25,000 of whom went on strike. Eventhough the Chief Constable of Glamorgan had about1400 police officers under his command, he asked fortroops and additional police. Troops were sent to the areabut held in reserve. The responsibility for maintaining lawand order was left with the local constabulary and the 300Metropolitan police officers ordered to the area by<strong>Churchill</strong>.On 7 November rioting broke out in Tonypandy,one of the towns in the Rhondda Valley. Sixty-three shopswere damaged, and one person was killed by accident.According to later reports, the police behaved withrestraint, utilizing only rolled-up mackintoshes inattempting to control the rioters.<strong>Churchill</strong> was both criticized and praised for thehandling of the disorder at Tonypandy. The Times chargedhim with weakness in failing to call in the troops, whilethe Manchester Guardian argued that his decision probably“saved many lives.” 6Interestingly, in later years <strong>Churchill</strong> was criticizedfor authorizing the use of troops at Tonypandy when, infact, he had not done so. (One commentator believesTonypandy is erroneously referenced because it is one ofthe few Welsh towns the English can pronounce.) 7In June 1911, strikes broke out in the Southamptondocks and spread to other locations. As the situation deteriorated,there were fears of a possible national railwaystrike. This led <strong>Churchill</strong> to suspend the rule that troopscould be provided only at the request of the local civicauthority. He authorized the deployment of forces at thediscretion of military commanders in the area.The strikes ended with the intervention of LloydGeorge. On 22 August 1911, <strong>Churchill</strong> spoke in theHouse of Commons, defending his actions. He said it hadbeen vital to keep the railroads running to protect thefood supply, arguing that a national railway strike wouldhave hurled the whole area into an “abyss of horror whichno man can dare to contemplate.” 8 He believed that theMetropolitan Police were not a strong enough force toprevent or quell disruptions that might have occurredanywhere in the country. <strong>Churchill</strong> acknowledged thatthere was some loss of life but argued that, in the longrun, lives were saved. 9Mobilizing the military outside of normal proceduresupset a number of people in <strong>Churchill</strong>’s Liberalparty, despite the Home Office’s measured response toprevious labor problems. In this instance his oratoricalstrengths may have contributed to an image more antilaborthan his actions suggest.The Battle of Sidney Street<strong>Churchill</strong>’s work in law enforcement was not confinedto labor disputes. In December 1910, a group of foreignanarchists was discovered digging a tunnel into a jewelryshop in London. The police arrived on the scene, and duringthe ensuing confrontation three police officers were killedand two were wounded. The criminals escaped but weretraced on January 3rd to a house on London’s Sidney Street.The police on the scene were armed but needed heavierweapons, so they requested approval from the Home Officeto use an armed platoon of Scots Guards. <strong>Churchill</strong> wassummoned from his bath to be briefed on the events atSidney Street and to sanction the use of the military.Although some believed he’d have been wiser to stay inhis tub, <strong>Churchill</strong> decided to go to the scene himself. Hearrived at Sidney Street—not surprisingly a conspicuouspresence. His level of involvement in directing the police hasbeen the subject of debate, but <strong>Churchill</strong> always maintainedthat he left the management of the siege to the officer incharge.At some point a fire started in the building the suspectshad occupied. <strong>Churchill</strong> confirmed a police order to the firebrigade to let the house burn rather than risk the lives of firefightersto protect those of criminals. >>FINEST HOUR 143 / 21

Arthur Balfour: “I understandwhat the photographer wasdoing, but what was the Rt.Hon. Gentleman doing?”Sidney Street, 3 January 1911,WSC in top hat.HOME SECRETARY...(<strong>Churchill</strong> denied that he gave the initial order.)Eventually two bodies were found in the building. One ortwo of the criminals were never accounted for, includingthe leader, “Peter the Painter,” who escaped and was neverheard from again. 10A newsreel camera captured <strong>Churchill</strong> at the scene,and one of the newspapers had a picture of him in top hatand fur collared coat, along with that of a photographerwho was covering the event. Referring to the photo,Arthur Balfour stated in the House of Commons:He was, I understand, in military phrase in what is knownas the zone of fire—he and a photographer were bothrisking valuable lives. I understand what the photographerwas doing, but what was the Rt. Hon. gentleman doing? 11<strong>Churchill</strong> conceded that Balfour’s comment was notwithout some justification.Suffragettes and Dirty CursOne of the characteristics <strong>Churchill</strong> brought topublic life was stating his views with clarity. He was notone to be all things to all people or to adopt a positionbecause it was the least offensive. <strong>Churchill</strong>’s record on theissue of women’s suffrage could not, however, be said to fitthat description.The issue was emotional and resolution morecomplex then one might first think from the vantagepoint of the 21st century. It was not simply a matter ofgiving the vote to females on the same basis as males. Inthe early 1900s the male vote was limited to householders.If the same standard had been applied to women, the votewould have been given to only a small percentage ofunmarried or widowed women. 12With the hope of finding a way through a difficultissue, a Conciliation Committee was established in thespring of 1910. TheCommittee’s leadershipwas seeking to removethe issue from theclamor of partisan politicsand find a solutionthat would be acceptableto a majority in theCommons. <strong>Churchill</strong>was approached and agreed to the use of his name as asupporter of the undertaking.The result of the Committee’s work was introducedin the House of Commons in July 1910. Despite hissupport of the Committee, <strong>Churchill</strong> spoke against thebill. This resulted in a heated exchange of correspondencebetween WSC and H.N. Braidsford, Honorary Secretaryof the Committee, who referred to his conduct as “treacherous.”<strong>Churchill</strong> replied that his support had beenlimited to the creation of the Committee, not any endproduct. Further letters followed.Braidsford and Lord Lytton claimed that <strong>Churchill</strong>had made positive comments to them about the specificproposal in private meetings. <strong>Churchill</strong> pointed out thatin addition to being private, those were preliminary discussionsand that Braidsford and Lytton should haveunderstood that his final views had to await analysis byexperts in the Home Office.Reviewing the correspondence gives a sense thatBraidsford and Lytton were most offended by <strong>Churchill</strong>’staking an active role in the debate and using his oratoricalskills against a cause they strongly supported. They mighthave understood and accepted a quiet neutrality, but wereupset by WSC’s statements and opposing vote.For <strong>Churchill</strong>’s part, he was deeply upset that privateconversations had been used against him in public, especiallyby Lytton, who had been a personal friend. It alsobothered him that supporters of suffragettes would accusehim of treachery when he had offered help to a group thathad badgered and bullied him during the course of severalelection campaigns.<strong>Churchill</strong> wrote a private memorandum on 19 July1910, outlining his recollections of his meetings and conversationson the suffrage issue. At paragraph 15 he notedthat in a meeting he had told Braidsford he could not votefor the bill but also “expressed his intention of not votingagainst the Bill.” 13This suggested he wasn’t going to vote at all—butFINEST HOUR 143 / 22

he changed his mind two days before the proposal’ssecond reading. He decided to speak and vote against themeasure for two reasons. First, research by his staff and hisown study of the bill revealed serious problems that madeit a bad piece of legislation and “deeply injurious to theLiberal cause.” 14 Second, he understood that both thePrime Minister and the Chancellor of the Exchequerwould oppose the proposal in public. Because emotionsran high, and there had even been threats of violence,<strong>Churchill</strong> said he would have considered it cowardly tohave sat on the sidelines.Whatever <strong>Churchill</strong>’s rights and wrongs on theFranchise Bill, he managed to alienate a number ofpeople, including some supporters. In a political sense, heowed nothing to the suffragettes. As he noted, they hadlong made his life miserable by regularly disrupting hisspeeches. Yet he had given his support to the Committee,so his subsequent conduct, even if justified in the particulars,left him open to the claim that he was saying onething and doing quite another.The Franchise Bill ultimately failed, and it soonbecame clear that Parliament would not take up the issueany time in the near future. This led to a demonstrationin Parliament Square by suffragettes and their backers onwhat came to be known as Black Friday (18 November1910). Not surprisingly, feelings continued to run high,and eventually there were clashes between the police anddemonstrators. Over 100 arrests were made. 15There was substantial criticism of how the policehandled the situation, including a letter from <strong>Churchill</strong>himself, who wrote the head of the Metropolitan Policeexpressing his concern that officers had been slow inmaking arrests. It was true that the police did not actquickly to arrest the demonstrators, but that approach wasconsistent with past practice. At the last minute <strong>Churchill</strong>had suggested a change in that practice but too late,according to the police commander, to get the message tothe officers on the scene.Press accounts focused on police excesses in firsttrying to control the crowd and then in making arrests.Even though <strong>Churchill</strong> promptly ordered the release ofthe arrestees, many suffrage leaders blamed him for theviolence and even accused him of ordering the releases toprevent the truth from being stated in court.A few days later, as the so-called Battle of DowningStreet took place, <strong>Churchill</strong> again appeared at a demonstrationin support of votes for women, and ordered thearrest of a participant. A few days later Hugh Franklin, asuffrage backer, attacked <strong>Churchill</strong> with a whip, shouting“Take that, you dirty cur!” 16 Franklin was charged withassault and sentenced to six weeks in prison. Suffrage continuedas a problem for the Liberal Party until theoutbreak of World War I in 1914 put the matter on theback burner.Prisoners and SentencesAmong the Home Secretary’s duties was reviewingdeath sentences considering mercy. <strong>Churchill</strong> took thisobligation seriously and, by all accounts, gave close attentionto each of the forty-three capital cases presented forreview. He reprieved twenty-one, which was a higher ratethan the 40 percent reprieved during 1900-09. 17Even though <strong>Churchill</strong> was not reluctant to showmercy in individual cases, he remained a supporter of thedeath penalty throughout his life. He did, however, viewthe ultimate punishment in a rather unusual light. In aletter to Sir Edward Grey he stated, “To most men—including all the best—a life sentence is worse than adeath sentence.” 18If this seems odd, it fit <strong>Churchill</strong>’s persona. He ledan adventurous life and appeared to have no fear of beingkilled. A long term of imprisonment would have beenmuch worse than death for a man of his temperament.Whether “most men” felt that way is another question.To the Home Secretary’s responsibility for England’sprison system <strong>Churchill</strong> brought a unique perspective—he was the only Home Secretary who was everincarcerated. In My Early Life he entitled the chapter onhis 1899 captivity by the Boers “In Durance Vile.”At the time <strong>Churchill</strong> took office, England wassending a large number of people to prison. In 1908-09over 180,000 people were incarcerated, over half forfailure to pay a fine, and a third for drunkenness. 19 Thegreat percentage of convicts were from the poorer classes,a fact which did not escape <strong>Churchill</strong>’s notice.He studied prison issues for several months aftertaking office. On 20 July 1910, he told the House ofCommons that one of the main principles for a goodprison system was to “prevent as many people as possiblefrom getting there.” 20 Some 90,000 people had been sentto prison in 1909 for failure to pay fines. Many wouldnever have gone to prison at all if they had been given areasonable period of time to pay their fines. <strong>Churchill</strong>advocated extending the time for payment. Even thoughhis proposal didn’t become law, the concept of more timewas accepted as national policy, reducing the number ofpeople sent to prison.The changed approach had a dramatic effect onthose charged with drunkenness. In 1908-09 over 62,000were imprisoned for failing to pay fines imposed for thatoffense. By 1918-19 the number was only 1600. 21<strong>Churchill</strong> also worked to extend the Children’s Actto those who were 16-21 years old, placing a greateremphasis on rehabilitation and alternative punishmentssuch as “defaulters drill” for petty offenses. He was reluctantto send any young person to prison unless a seriousoffense was involved. To his credit, <strong>Churchill</strong>’s attitudewas affected by the reality that those who were sent awaywere almost always sons of the working class. He pointedout that many of the same acts, if committed by a >>FINEST HOUR 143 / 23

HOME SECRETARY...young man at Oxford, were not punished in any way. 22 Asa result of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s efforts, far fewer young peopleentered the country’s prisons.One of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s duties was to write regular memosto the King on House of Commons activities. Though thisfalls outside the law and order category, it is worth a discussionbecause of WSC’s approach to the task.On 10 February 1911, <strong>Churchill</strong> wrote the King:“…as for tramps and wastrels there ought to be properlabour colonies where they could be sent….it must not,however, be forgotten that there are idlers and wastrels atboth ends of the social scale.” 23 Greatly offended, GeorgeV concluded that WSC’s view was “very socialistic.” 24 TheKing’s reaction prompted a series of notes between<strong>Churchill</strong> and Lord Knollys, the King’s private secretary.At one point <strong>Churchill</strong> suggested that the duty ofupdating the King should perhaps “be transferred to someother minister.” He finally calmed down when the King,through Lord Knollys, assured him that he wanted<strong>Churchill</strong> to continue, and that his letters were “alwaysvery interesting.” 25The exchange was enough for Knollys to commentthat <strong>Churchill</strong> “means to be conciliatory I imagine, but heis rather like ‘a bull in a china shop.’” 26 Knollys mighthave overstated things, but there’s no denying that wherever<strong>Churchill</strong> served, there was action and controversy.Summing UpEven though his time as Home Secretary was a briefand little-known part of his public life, <strong>Winston</strong> was still<strong>Winston</strong>. The issues he faced provoked controversy andintense feelings. His actions prompted both praise andstinging criticism. Even when his actions were reasonableand temperate, his oratorical flourishes could at timesleave the impression he was following an extreme course.Whatever else might be said about <strong>Churchill</strong>’s timeat the Home Office, there can be no dispute that hisunique personality and strong views guaranteed interestingtimes. After approximately twenty months asHome Secretary, the controversial <strong>Churchill</strong> went on tobecome First Lord of the Admiralty—and times remainedas interesting as ever.Endnotes1. Roy Jenkins, <strong>Churchill</strong> (Macmillan, 2001), 170.2. Paul Addison, <strong>Churchill</strong> on the Home Front 1900-1955(London: Pimlico, 1995), 128.3. Randolph S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, CompanionVolume II, Part 2, 1907-1911 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969), 1172.4. Randolph S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, vol. II, YoungStatesman 1901-1914 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1967), 358.5. Ibid., 363.6. Ibid., 364.7. “Leading <strong>Churchill</strong> Myths,” Finest Hour 140, Autumn 2008, 11.8. Young Statesman, 367.Hendon Aviation meeting, 12 May 1911: <strong>Churchill</strong>, second from right, chatswith newspaper magnate Lord Northliffe; Mrs. <strong>Churchill</strong> shades her eyes atleft. Although still Home Secretary, WSC was now takng a serious interest inaircraft and flying, which would bear useful fruit in World War I.9. Ibid., 371-37210. Ibid., 394.11. Ibid., 395.12. Addison, 132.13. Randolph S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, CompanionVolume II, Part 3, 1911-1914 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969), 1452.14. Ibid., 1453.15. Addison, 136.16. WSC, Companion Volume II, Part 3, 1911-1914, 1459.17. Addison, 119.18. Young Statesman, 403.19. Ibid., 373.20. Addison, 114.21. Young Statesman, 375.22. Ibid., 376.23. Ibid., 418.24. Ibid., 419.25. Ibid., 423.26. Ibid., 423.Other Sources<strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, Thoughts and Adventures (Wilmington,Delaware: ISI Books, 2009).Ted Morgan, <strong>Churchill</strong>: Young Man in a Hurry (New York:Simon & Schuster, 1982).Donald Rumbelow, The Siege of Sidney Street (New York: St.Martin’s Press, 1973).Maxwell P. Schoenfeld, Sir <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>: His Life andTimes (Malabar, Fla.: Krieger, 1986).Websites<strong>Churchill</strong> Centre: “Action This Day, A Daily Chronicle of<strong>Churchill</strong>’s Life; Young Statesman: 1901-1914” (http://www.winstonchurchill.org).<strong>Churchill</strong> Archives Centre, Cambridge: Chartwell Papers,CHAR 12: Home Office (http://www.chu.cam.ac.uk).✌FINEST HOUR 143 / 24