Montserrat Survey of Living Conditions (MSLC) Executive Summary

Montserrat Survey of Living Conditions (MSLC) Executive Summary

Montserrat Survey of Living Conditions (MSLC) Executive Summary

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>on a review <strong>of</strong> their Sustainable Development Plan 2008-2012 (SDP). This review provides an idealmechanism for some <strong>of</strong> the Poverty Action Programme recommendations to be rapidly incorporated intothe new version <strong>of</strong> the MSDP.2 Background and Context (Chapter 2)2.1 Geographic and Historical Setting<strong>Montserrat</strong> is one <strong>of</strong> the Leeward Islands in the Eastern Caribbean, lying 43km south-west <strong>of</strong> Antigua and64km north-west <strong>of</strong> Guadeloupe. It is approximately 102 sq km (16 km long and 11 km wide) andgrowing slowly due to volcanic deposits on the southeast coast <strong>of</strong> the island. The topography is entirelyvolcanic and very mountainous, with a rugged coastline with dramatic rock faced cliffs rising from the sea.<strong>Montserrat</strong> was populated by Arawak and Carib people when it was claimed by Christopher Columbus forSpain on his second voyage in 1493. The island fell under English control in 1632 when a group <strong>of</strong> Irishfleeing anti-Roman Catholic sentiment in Saint Kitts and Nevis settled there. The import <strong>of</strong> slaves startedat much the same time and an economy based on sugar, rum, arrowroot and Sea Island cotton wasestablished during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Slavery was abolished in 1834 following thegeneral emancipation <strong>of</strong> slaves within the British Empire which occurred in that year.Falling sugar prices during the nineteenth century had an adverse effect on the island's economy and in1869 the British philanthropist Joseph Sturge formed the <strong>Montserrat</strong> Company to buy sugar estates thatwere no longer economically viable. The company planted limes and started production <strong>of</strong> the island'sfamous lime juice, set up a school, and sold parcels <strong>of</strong> land to the inhabitants <strong>of</strong> the island, with the resultthat much <strong>of</strong> <strong>Montserrat</strong> came to be owned by smallholders.From 1871 to 1958 <strong>Montserrat</strong> was administered as part <strong>of</strong> the Federal Colony <strong>of</strong> the Leeward Islands,becoming a province <strong>of</strong> the short-lived West Indies Federation from 1958 to 1962. It is currently one <strong>of</strong>Britain’s remaining overseas territories with the Queen as head <strong>of</strong> state, a governor appointed by theQueen and a democratically elected Chief Minister.The last years <strong>of</strong> the 20th century, however, brought two events which devastated the island. In September1989, Hurricane Hugo struck the island with full force, damaging over 90 percent <strong>of</strong> the buildings andvirtually wiping out the then burgeoning tourist trade. Within a few years, however, the island had largelyrecovered - only to be struck again by the major eruptions <strong>of</strong> the Soufriere Hills volcano in 1995 and 1997.Two and half years <strong>of</strong> intense volcanic activity saw the southern, most populated and most fertile part <strong>of</strong>the island, evacuated and declared unsafe. Plymouth, the capital and the territory’s industrial, commercial,and government centre, was almost totally destroyed along with the island’s airport and hospital; manypeople lost their houses and had to be evacuated. Over half the population left and a steep economicdecline followed. Reconstruction efforts started in earnest in the early 2000s and the northern, habitablepart <strong>of</strong> the island now has government <strong>of</strong>fices, schools, a hospital and an airport along with new housingestates and much improved roads. The island however remains largely dependent on assistance from theBritish Government.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES2

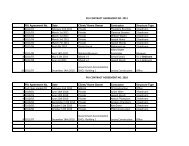

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>2.2 PopulationThroughout most <strong>of</strong> its recorded history the population <strong>of</strong> <strong>Montserrat</strong> has varied between 10,000 and12,000 with a peak <strong>of</strong> 14,000 being achieved in 1946 (Table ES.1). However while the 1989 hurricane hadonly a minor impact on the population, the impact <strong>of</strong> the volcanic eruption has been catastrophic: in 1997,the population was around 3,400 – only 30% <strong>of</strong> the 1991 figure. By 2001, it had ‘recovered’ to around4,500 and to 5,000 by 2006 2 . The impact <strong>of</strong> the eruption on the geographic distribution <strong>of</strong> population isshown in Figure ES1.With a population as small as this, the start <strong>of</strong> completion <strong>of</strong> large construction projects can leadsignificant changes in population, as workers and their dependents arrive and leave; population growthrates can thus fluctuate significantly from year to year. Since 2000, live births and deaths have bothaveraged around 50 annually implying that there is a negligible natural increase in the population.Table ES1. Population Change, 1881-2006Figure ES1. Population Distribution, 1991 and2001Year Population AnnualGrowth rate60001881 10,0831891 11,762 1.6%1901 12,215 0.4%1911 12,196 0.0%1921 12,120 -0.1%1946 14,333 0.7%1960 12,167 -1.2%1970 11,458 -0.6%1980 11,606 0.1%500040003000200010001991 10,639 -0.8%1997 3,338 -17.6%2001 4,491 7.7%2006 5,031 2.3%0Plymouth1991 2001Rest <strong>of</strong> StAnthonySt George(St John'sMongo Hill,Barzeys)St Peter(isles Bay/Happy Hill)The population <strong>of</strong> all age groups has declined since the eruption but these changes have not affected allage groups equally. In 2001, the main changes were the much increased proportion <strong>of</strong> population in theworking age groups and a corresponding decrease in the population under the age <strong>of</strong> 15 whose proportiondeclined from just over a quarter to under 20%. By 2006, the proportion <strong>of</strong> the elderly had decreasedlargely due to the increased proportion <strong>of</strong> under 15s. The increased number <strong>of</strong> children implies both ageneral stabilisation <strong>of</strong> the population and that migrants are increasingly bringing their children. Howeverthe very low proportion <strong>of</strong> 15-24 year olds (11% compared with 17% in 1991), is clear evidence <strong>of</strong> a‘brain-drain’ as school leavers depart to find tertiary education and employment <strong>of</strong>f the island.2 Initial results from the 2011 Census give a population <strong>of</strong> around 5,000, i.e. little change since 2006.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES3

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>Average household size was 2.4 persons in 2008/09 which, while low by Caribbean standards, is slightlyhigher than after the eruption when it dropped to 2.1 persons. The proportion <strong>of</strong> households withspouses/ partners has increased to 38%, much higher than in 2001 when it was only 29% while theproportion <strong>of</strong> single person households had decreased from almost 50% in 2001 to 35%. Around 40% <strong>of</strong>households are female-headed, similar to the 1991 proportion. All these indicators reinforce the view thatthe population structure <strong>of</strong> the island is gradually stabilising from its post-eruption structure when a largenumber <strong>of</strong> households fragmented.In 2008/09, 29% <strong>of</strong> household heads were foreign-born but a substantial proportion <strong>of</strong> these hadachieved belonger status. If this group is excluded, the proportion <strong>of</strong> non-national heads on the island isaround 15%.2.3 The EconomyThe economy <strong>of</strong> <strong>Montserrat</strong> today is the result <strong>of</strong> an array <strong>of</strong> unique factors and developments followingboth Hurricane Hugo and the volcanic eruptions in which social and economic structures and the island’sinfrastructure were decimated; large parts <strong>of</strong> the island were made (and remain to this day) uninhabitable.As a British Overseas Territory, <strong>Montserrat</strong> has been able to access loans and grants from the UnitedKingdom to rebuild and <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians were able to leave their homes for jobs and family in the UK,thereby decreasing pressure on the post-eruption economy. In consequence, the recovering economy isbased mainly on services (especially government) and construction, with little value added in the traditionalsectors <strong>of</strong> tourism and agriculture (Figure ES2).Through grants, loans and support from <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians living overseas, <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians have been able tomaintain a reasonable material lifestyle 3 , as measured by GDP per capita. In 2004, <strong>Montserrat</strong>ian GDP percapita in 2006 at around EC$22,000 was 50% higher than the ECCB average and 3 rd highest <strong>of</strong> the eightmember states.Nevertheless, the current weakness <strong>of</strong> the economy is evident. In 2006, in constant dollars, GDP was only53% <strong>of</strong> the level achieved in its pre-Hugo (1987) level (Figure ES3). Were it not for the fact that many<strong>Montserrat</strong>ians left the island following the volcanic activity, per capita economic activity would be muchlower. The recent sluggish performance is largely the result <strong>of</strong> some large public sector projects beingcompleted with only the mining and quarrying sector showing growth as a result <strong>of</strong> exports <strong>of</strong> volcanicsand. In 2008, the economy grew by around 4% but inflation almost reached 5% resulting in a decline inreal GDP 4 . ECCB forecasts that the economy will continue to remain flat in the near term; risinginternational oil prices and the North American recession will further increase consumer prices. TheGovernment <strong>of</strong> <strong>Montserrat</strong> is forecasting GDP growth <strong>of</strong> 3% in both 2008 and 2009 based on the startup<strong>of</strong> construction projects at Little Bay and Government Headquarters, among others.3 In 2008/09: 53% <strong>of</strong> households had a motor vehicle; over 85% had fridges, TVs and telephones (landline or cell);40% had computers with most <strong>of</strong> these having internet access.4 GOM, Budget Speech, 2009.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES4

()EC$ x million<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>Figure ES2 : <strong>Montserrat</strong>, GDP by Sector,2006Figure ES3. <strong>Montserrat</strong>: GDP in constant EC$ millions,1987-2006Fig. 3 GDP in Constant Dollars(EC$ x million)180.0160.0140.0120.0100.080.060.040.020.00.01987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006The Government SectorFigure ES4: Government Expenditures and RevenuesEC$millions100806040200-20-40-602002 2003 2004 2005 2006-80Current Revenue Current Expendiiture Current Balance before GrantsSource: 2006 Annual Economic and Financial Review, ECCBGovernment activity is the main driver<strong>of</strong> the <strong>Montserrat</strong> economy. Giventhe natural disasters <strong>of</strong> the past 25years, the contraction <strong>of</strong> economicactivity and the need to rebuildinfrastructure,governmentexpenditures are greater than revenueinflows (Figure ES4). The resultingnegative balance is expected tocontinue over the short to mediumterms.Tax revenues (duties and levies, licensefees, consumption tax, etc.) accountfor about 45% <strong>of</strong> Governmentrevenue. On the expenditure side,personal emoluments 5 and pensionsfor government employees account forabout 55% <strong>of</strong> Governmentexpenditures.5 These will include teachers and health workers as well administrative <strong>of</strong>ficers.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES5

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>Total social spending (education, health and social welfare) rose from EC$15.6 million in 2002 to EC$23.4million in 2007; around 1/3rd <strong>of</strong> this expenditure was on education and 2/3rds on health and socialwelfare. This expenditure has maintained a fairly constant share <strong>of</strong> total government recurrent expenditure<strong>of</strong> around 25%.2.4 EmploymentBetween 2001 and 2006, reconstruction activities led to employment increasing by almost 50% andunemployment dropping slightly to 12%. Women made up 44% <strong>of</strong> the active population. The pattern <strong>of</strong>employment also changed substantially between 1991 and 2001 with the government becoming by somemargin the most important sector accounting for 45% <strong>of</strong> total employment – a pattern that had changedlittle by 2008/09 when the self employed accounted for 19% <strong>of</strong> those working and 35% were privatesector employees. The principal trend in terms <strong>of</strong> occupational groupings, evident since 1991, is increasingproportions in both the most skilled (white collar) and least skilled (elementary) occupations; in contrast,the proportions <strong>of</strong> sales and skilled manual workers both decreased (Table ES2).Table ES2. Employment CharacteristicsType <strong>of</strong> Employment 1991 2001 2008/09Change 1991-2008/09Government/ Statutory Bodies 27% 45% 46% +19%Private employee 55% 39% 35% -20%Self employed 18% 16% 19% +1%Occupational GroupingManagerial, Pr<strong>of</strong>essional, Technical 24% 30% 34% +10%Clerical and Sales 24% 27% 21% -3%Crafts and Skilled Manual 34% 25% 18% -16%Unskilled Elementary 18% 18% 26% +8%Total 100% 100% 100%Sources: 1991 and 2001 Censuses, Listing <strong>Survey</strong> 2006, SLC 2008/09Employment in construction and government (including health and education) dominate the economywith around 60% <strong>of</strong> all employment. There is negligible employment in agriculture or manufacturing.In 2001, non-nationals accounted for 22% <strong>of</strong> employment on the island. While they were found in alloccupations and industrial sectors, the proportions vary substantially: non-nationals are ‘over-represented’ 6in the unskilled, craft and pr<strong>of</strong>essional groups, i.e. at both at both ends <strong>of</strong> the skills continuum. In terms<strong>of</strong> industrial sectors, they provide at least 30% <strong>of</strong> employment in domestic service, hotels, constructionand manufacturing; conversely, they are under-represented in government which is the most importantemployment sector <strong>of</strong> all.6 I.e. NNAT share <strong>of</strong> employment in an occupational group/ industrial sector is greater than their share <strong>of</strong> totalemployment.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES6

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>2.5 Education, Health and HousingEducation in <strong>Montserrat</strong> is compulsory for children between the ages <strong>of</strong> 5 and 14, and free up to the age<strong>of</strong> 17. Attendance is essentially 100% as is the transition from primary to secondary. Youth and adultliteracy is also very high.Health conditions in <strong>Montserrat</strong> are generally good:Life expectancy at birth was 81.0 years for women and 76.5 years for men with additional gainsexpected for both sexes. This compares favourably with other OECS islands.Only 1 infant death has been recorded since 1998 and none <strong>of</strong> children aged under 5 years.There were no reported cases <strong>of</strong> protein energy malnutrition.The most common recorded communicable diseases from 1998 to 2006 are respiratoryinfections (39%), influenza (33%) and gastroenteritis (14%). These diseases are prevalent invirtually every country. In contrast, there have been no cases <strong>of</strong> the communicable childhooddiseases (measles, etc.) since 1998.Only 2 cases <strong>of</strong> AIDS have been recorded on the island since 1998 although 21 persons testedpositive for HIV infection during the same period. Given that some <strong>of</strong> these left the island, theoverall rate <strong>of</strong> incidence amongst adults (15-49 years) would be substantially below theCaribbean average.The main medical concerns at present are diabetes and hypertension which respectively afflictapproximately 6% and 10% <strong>of</strong> the population; prevalence rates are not dissimilar to those in the USADiabetes along with heart disease are the main causes <strong>of</strong> death (respectively 21% and 44% <strong>of</strong> all deathsbetween 2003 and 2006) with cancers (13%) accounting for a large proportion <strong>of</strong> the remainder. Anotherhealth concern is an increasing prevalence <strong>of</strong> dementia with many elderly persons receiving psychologicalservices and with over 100 being cared for in government institutions.Housing tenure has changed considerably sincethe eruption (Figure ES4) with the proportion<strong>of</strong> households owning their property decreasingby almost half from 72% to 38% between 1991and 2001. Although there were increases inprivate renting and rent free housing, the majorincrease was in government rentedaccommodation which provided for one inevery 6 households in 2001. Currently, thesituation has improved substantially with theproportion <strong>of</strong> owned dwellings increasing to59% with a corresponding decline in the rentedsector – a reflection factors such as theconstruction <strong>of</strong> Lookout and the closure <strong>of</strong>temporary hostels.Figure ES4: Housing Tenure, 1991, 2001, 2008% <strong>of</strong> hholds80%72%70%59%60%50%43%38%40%31%30%20%20%12%10%10%7% 7%0%0%0%Owned Rented Rent Free Other1991 2001 2008/09 Housing Tenure<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES7

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>The great majority <strong>of</strong> houses in <strong>Montserrat</strong> are single dwellings, have piped water, proper sanitation,electricity and use gas/ LPG for cooking. Overcrowding (defined as households with fewer living roomsthan persons), affected 21% <strong>of</strong> households, a similar proportion to that prevailing in 1991 7 . Nonetheless,around 30% <strong>of</strong> dwellings do not have concrete ro<strong>of</strong>s – although this is substantially lower than theequivalent 2001 proportion, 45%.3 Poverty in <strong>Montserrat</strong> (Chapter 3)3.1 The Definition <strong>of</strong> PovertyPoverty is most <strong>of</strong>ten defined on the basis <strong>of</strong> an indigence (or severe poverty) line based on minimumfood requirements, and a general poverty line (minimum food requirements plus an element <strong>of</strong> non-foodexpenditure) derived according to the CDB methodology. In 2009, the annual indigence line is aroundEC$4,735 (c. EC$13/US$5 per day) for an adult male while the poverty line is around EC$14,400 (c.EC$39.5/US$15 per day).Current definitions <strong>of</strong> poverty are more wide-ranging than those based on income alone. They includeconsideration <strong>of</strong>, inter alia, living conditions, access to health and education, and less easily defined notionssuch as vulnerability, voicelessness, powerlessness, and lack <strong>of</strong> opportunity. The general concept <strong>of</strong> ‘wellbeing’has been used in this study to bracket these non-income aspects <strong>of</strong> poverty – this is an importanttheme <strong>of</strong> this CPA.In general, there is a high correlation between lack <strong>of</strong> income and lack <strong>of</strong> well-being. However this is notalways the case – some people and households living below the poverty line may not feel insecure orthreatened. Conversely, others, with incomes above the poverty, may experience lack <strong>of</strong> well-beingresulting from factors such as family disruption, teenage pregnancy, crime, drug abuse or be at risk <strong>of</strong>falling into poverty from one or more <strong>of</strong> these factors.3.2 The Extent <strong>of</strong> Poverty in <strong>Montserrat</strong> in 2008/09In late 2008/ early 2009, when the SLC was carried out, 25% <strong>of</strong> <strong>Montserrat</strong>ian households 8 and 36% <strong>of</strong>the population are poor. The level <strong>of</strong> indigence is however low at 2% <strong>of</strong> households and 3% <strong>of</strong> thepopulation 9 . Around 20% <strong>of</strong> both population and households are classified as vulnerable (i.e. withexpenditures up to 25% above the poverty line). Overall, 75% <strong>of</strong> households and 64% <strong>of</strong> the populationare not poor; if those most vulnerable to poverty are excluded, 56% <strong>of</strong> households and 44% <strong>of</strong> thepopulation are neither poor nor vulnerable to poverty. (Figure ES5).7 The 2001 census did not tabulate the number <strong>of</strong> habitable rooms.8 Persons residing in collective households, e.g. hostels, care homes, the hospital and the prison, are excluded.9 As with any sample survey, these estimates are subject to sampling error, which as a proportion <strong>of</strong> the estimate,increases with smaller percentages. The 90% confidence level for households in severe poverty is ± 1.4% while theconfidence level for those in poverty is ± 3.6%.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES8

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>These data are generally consistent with thePPAs which indicated both low levels <strong>of</strong>severe poverty and high levels <strong>of</strong> poverty/hardship amongst the population – thewords ‘struggle’, ‘surviving’, ‘hardship’appear over 500 times in the discussionswhile issues related to the high price <strong>of</strong>food and utilities were mentioned byvirtually everyone. Conversely, there werevery few mentions relating to ‘hunger’which corroborates the low statistical level<strong>of</strong> severe poverty. The only groups seen asbeing relatively unaffected by this situationwere senior civil servants, business peopleand politicians - around a third <strong>of</strong> thoseemployed.Figure ES5. Poverty in <strong>Montserrat</strong>, 2009100%90%80%44%70%56%60%50%20%40%19%30%20%32%23%10%0%2% 3%HouseholdsPopulationIndigent Poor not indigent Vulnerable Not PoorTable ES3 provides a comparison <strong>of</strong> poverty levels in <strong>Montserrat</strong> with those <strong>of</strong> other Caribbeancountries 10 . <strong>Montserrat</strong>’s poverty level is higher than most <strong>of</strong> the other countries, the exceptions beingBelize (which was carried out about the same time) and Guyana. The food share percentage <strong>of</strong> the povertyline is a good indicator <strong>of</strong> relative poverty levels, as this variable traditionally decreases with affluence.<strong>Montserrat</strong>, at 34%, is lower than all the cited countries except St Lucia.CountryTable ES3. International Comparisons <strong>of</strong> PovertyYear**% Popindigent% H’holdsindigent% poppoor*% H’holdspoorGinicoeff.Food as % <strong>of</strong>Poverty Line<strong>Montserrat</strong> 2008/09 3 2 36 25 0.39 34%Antigua 2005/6 4 3 19 - 0.48 39%Barbados 2010 9 - 19 15 0.47 -Belize 2009 16 10 42 31 0.42 58%Dominica 2009 3 - 29 23 0.44 39%Guyana 2006 19 - 36 - - -St. Kitts 2008 1 - 24 - 0.40 -Nevis 2008 0 - 16 - 0.38 -St. Lucia 2005 2 1 29 21 0.42 31%St Vincent 2007/8 3 - 30 - 0.40 44%Trinidad & Tobago 2005 1 - 17 - 0.39 38%Based on this table, <strong>Montserrat</strong>’s low level <strong>of</strong> indigence is similar to that <strong>of</strong> most other countries.Conversely its level <strong>of</strong> poverty is higher than most, the exceptions being Belize (which was carried out10 These comparisons are not straightforward as the surveys were not undertaken at the same time and the calculationmethodologies, although similar, do vary. Furthermore, the current study was undertaken at a period when there hadbeen a serious hike in food prices.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES9

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>about the same time) and Guyana. The food share percentage <strong>of</strong> the poverty line is a good indicator <strong>of</strong>relative poverty levels, as this variable traditionally decreases with affluence. <strong>Montserrat</strong>, at 34%, is lowerthan all the cited countries except St Lucia. <strong>Montserrat</strong>’s Gini coefficient situates it firmly amongst themajority <strong>of</strong> the countries shown in terms <strong>of</strong> income inequality.3.3 Characteristics <strong>of</strong> Poverty in <strong>Montserrat</strong> in 2009In terms <strong>of</strong> demographic characteristics, the findings are similar to those <strong>of</strong> many other CPAs and can besummarized as follows:Children (under 15 years) experience by far the highest poverty rate. This group accounts for over athird <strong>of</strong> the poor population.Those over 30 years, including the elderly, have a below average poverty rate. The elderly account forlittle more than 10% <strong>of</strong> the poor population.There is no difference in the incidence <strong>of</strong> poverty between males and females. Nor is there asignificant difference between male and female headed households.There is an unambiguous correlation between household size and poverty (Figure ES5). Largerhouseholds are much more likely to be poor and they account for a disproportionate proportion <strong>of</strong>poor households. Specifically, households with more than 2 persons account for over 60% <strong>of</strong> poorhouseholds compared with 34% <strong>of</strong> all households; the poverty rate amongst this group is around45%, almost double the national average. In contrast, the poverty rate for single person households isonly 11%. These contrasts are even more acute when population rather than households are used –over 80% <strong>of</strong> the poor population lives in households with more than 2 persons. The averagehousehold size <strong>of</strong> poor households is 3.5 persons compared with 2.1 persons for not poorhouseholds.Figure ES6. Poverty and Household size, <strong>Montserrat</strong>, 200950%45%40%35%30%25%20%15%10%5%0%47%35% 35%26%24%15%13%4%1 2 3-4 5+Household Size (persons)% <strong>of</strong> Poor Households % <strong>of</strong> Poor Population<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES10

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>Higher levels <strong>of</strong> poverty are also associated with:Households where no one is employed.Households headed by persons with only primary education.<strong>Montserrat</strong>ian-headed households.Overcrowded and renting households (virtually everyone has access to piped water, sanitation andelectricity.Lower levels <strong>of</strong> vehicle and computer ownership – but not telephones, fridges, TVs and washingmachines.The situation is however more complex than is implied by the above statistics which, in most cases, arenot statistically significant:In every category described there are more not poor people than poor people.Just because a group exhibits a lower than average poverty rate, does not mean that there are notimportant poverty related issues that need to be addressed.The data relate only to income poverty and do not take account <strong>of</strong> issues related to wellbeing.3.4 Difficulties faced by the PoorThe PPAs provide information on the difficulties encountered by different groups <strong>of</strong> the poor. The‘primacy’ <strong>of</strong> economic hardship came out strongly in the PPAs with more mentions relating to high prices,low wages and lack <strong>of</strong> employment opportunities - resulting from the sluggish economy and the spike inoil and food prices that occurred at the end <strong>of</strong> 2008/ early 2009 - than for all other issues combined. As aresult, many households are finding it hard to cope with weekly food costs, loan repayments, educationcosts and utility bills (electricity disconnections are increasing).For poor family households (55% <strong>of</strong> poor households have children), these difficulties can lead toadditional pressures on family relationships potentially giving rise to a range <strong>of</strong> adverse impacts onwellbeing:“I feel confused, frustrated and, powerless. When I get up in the morning and I don’t have sugar to put in mychildren tea, I have to ask the neighbour. I feel very stress. In <strong>Montserrat</strong> you hardly get someone to ‘stretch’for you. You have to fight the battle for yourself. I feel that my life is at risk, because I have a heart problem.I am sick and I cannot come up with money to go to the doctor. I feel at risk. Really tough, I have stress Ihave children to feed. I eat what the doctor told me eat, but it is very difficult. I have husband who is not“stretching” for me. He is not helping me.” (FGD Migrant Women, Salem)In turn, these pressures can give rise to a range <strong>of</strong> abusive, anti-social and risky behaviours: family breakup, domestic violence, child abuse, drug-taking, criminality and teenage pregnancy 11 , all <strong>of</strong> which increasethe risk <strong>of</strong> continuing and inter-generational poverty:11 Note that these can also arise independently <strong>of</strong> economic issues; see 3.7 below.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES11

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>“Because parents have to work two or more jobs to make ends meet, there is no more interaction betweenparents and children. Children are not monitored properly by their parents and do not go home after schoolwhich may be a cause <strong>of</strong> delinquency”. (FGD Salem)The traditional form <strong>of</strong> support for the elderly is by family members. This type <strong>of</strong> support is in declineworldwide and, on <strong>Montserrat</strong>, has been accelerated by the volcanic eruption, which eliminated many <strong>of</strong>savings and assets as well as leading to family fragmentation. The elderly are thus increasingly dependenton pensions and social welfare - the majority <strong>of</strong> households with elderly persons have income from thesesources. Their prime concerns are thus different from those <strong>of</strong> other vulnerable groups: the low level <strong>of</strong>welfare/ pension payments, loneliness due to the absence <strong>of</strong> family members, access to health services,both <strong>of</strong> which can be compounded when mobility is impaired. These non-income issues can affect notpoor as well as poor elderly persons 12 .The economic downturn and the high prices have affected many migrants on the island in similar ways tonationals: increased unemployment, reduced working hours and increased pressure, sometimes intense, onhousehold budgets. For poor and less skilled migrants, the major issues <strong>of</strong> concern are those related toimmigration and work permits (the actual regulations and their application), differential access to healthcare and a sense <strong>of</strong> insecurity and vulnerability arising from their perception that their presence is resentedby many <strong>Montserrat</strong>ian. Conversely, there is a perception amongst some <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians that migrants aretaking their jobs 13 . There is thus a palpable sense <strong>of</strong> mutual distrust between migrants and <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians.Housing is mentioned over 60 times in the FGDs and KIIs, and particularly by the households relocatedfrom the devastated area, many <strong>of</strong> whom are living in rented property or shelters, and who are unable toaccess the funds needed to buy or build a new house <strong>of</strong> their own. Debt to foreign banks for mortgageson properties lost under the eruption remains a hindrance to some, as well as being an impediment to thereturn <strong>of</strong> non-resident <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians. The accommodation for poorer renting households is <strong>of</strong>ten lowstandard, overcrowded and inadequately maintained. At the same time, northern residents are critical thatvirtually all housing assistance has gone to relocatees and almost none to them, despite the fact that manylost their jobs with the eruption.On the other hand, non-financial issues related to infrastructure (e.g. water, electricity or roads) oreducation received substantially fewer mentions.There is fairly widespread criticism <strong>of</strong> the government’s performance, although some say that the GoM isdoing what it can but is constrained by outside factors, namely the macro-economy and the financialcontrol exerted by the UK government. These criticisms range from the failure to impose price controls orreduce taxes to a perception that the administration does not ‘care’ for the needy or listen enough to theirviews, and more seriously, a perception that the government is only looking after its own, e.g. throughfavouritism in the allocation <strong>of</strong> housing and jobs, protected pensions, as well as unrealised electionpromises. None <strong>of</strong> these occurs frequently in the PPAs but the overall impression <strong>of</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong> trust ispervasive as is a belief that the government holds the key to their future wellbeing.12 The quality and accessibility <strong>of</strong> health care is also the greatest concern <strong>of</strong> the physically and mentally-challenged.13 “We are double dying – people leaving and non-nationals are taking jobs” (Salem FGD).<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES12

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>3.5 Coping StrategiesInadequate incomes whether due to low wages, unemployment, insufficient government assistance or lack<strong>of</strong> family support for those too old, too young or too disabled to work, necessitates the adoption <strong>of</strong>coping strategies. The main coping strategies identified during the study are shown in Table ES4. Ingeneral, these vary little between different groups; nor are they very different from those found in mostCaribbean poverty assessments.Table ES4: Coping StrategiesCopingStrategyBackyardgardeningSecondoccupationsReduced foodconsumptionReducingexpendituresespeciallyutilitiesFamilyassistance /remittancesGettingassistancefrom NGOsUsing savings/ selling assetsKIIs/ FGDsmentioningWho doesit?65% Those withland/ gardens44% The ablebodied.CommentsHas always existed but <strong>of</strong>ten hampered by poor soil and looseanimals and pests (iguanas) which destroy the crops.Includes renting rooms, both parents seeking jobs; cash-in-handjobs such as ironing, gardening, cleaning, etc.35% All Eating less; buying food on a ration basis or wholesale; usingstaples only; foraging. Leads to less nutritious diets and,infrequently, hunger.25% All those notin sheltersSee data above. Manifestations include using less light,purchasing energy saving light bulbs, cooking less, maximisingwash loads, minimizing water use, no longer using electric stoves,coal pot cooking*; walking rather than taking the bus; reducedsocial activities. By far the most prevalent is delaying payments.49% All Little evidence that remittances are having a significant onreducing poverty: under 6% <strong>of</strong> households received overseasremittances and in virtually all cases, these did not affect thepoverty status <strong>of</strong> the household. Net remittances are negative asNNATs remit more overseas than are received on the island.NaProstitution 3mentionsMostly theelderly andthe disabledNa All Rarely mentioned.Young womenPrincipally the Red Cross and churches but also Meals on Wheels(68 total mentions in all PPAs). Assistance is mainly in food. Bothorganisations rely on donations for the assistance they provide.One <strong>of</strong> the most extreme and infrequent.Emigration Na All More close family members had left the island than had arrived inthe last 5 years. This was also the primary coping strategyfollowing the eruptions.3.6 Priority NeedsThe PPAs also obtained information on residents’ views as to their priority needs. Figure 3.7 shows thedifferent patterns <strong>of</strong> policy suggestions obtained from the KIIs/ FGDs, which can be expected to takemore <strong>of</strong> an overview <strong>of</strong> the overall situation and the SSIs which are more likely to reflect the concerns <strong>of</strong>individual households. While the Figure shows broadly similar patterns with similar, and greatest, emphasison economic issues, the SSIs give greater relative importance to health, migration and governance issues.In contrast, the KIIs/ FGDs put more emphasis on agriculture, recreation facilities and infrastructure/major projects.The PPAs also provided a substantial number or more detailed suggestions, many <strong>of</strong> which have beenincorporated into the Poverty Action Programme (see section 6 below).<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES13

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>Figure ES7: Priority Needs as expressed in the PPAsPrices/ JobsAgricultureSSIs (responses=113)26%5%15%6% 4%12%4%12% 8%8%HealthTraining / EducationHousingSocial ServicesRecreation/ SportsFGDs/KIIs (responses =208)26%13%8%8%6%11%8%5% 4%12%Migration IssuesGovernanceInfrastructure/ MajorProjects0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%% <strong>of</strong> Responses3.7 The Causes <strong>of</strong> Poverty in <strong>Montserrat</strong>The primary causes <strong>of</strong> poverty on <strong>Montserrat</strong> are economic. This bears out recent research undertaken bythe World Bank 14 which shows that economic factors - lack <strong>of</strong> employment 15 , low wages and high prices -as the main causes <strong>of</strong> poverty - were the reasons that two thirds <strong>of</strong> households fell into poverty. Thesefactors were also the primary concern, and by a considerable margin, <strong>of</strong> every group interviewed duringthe PPAs be they unemployed, low waged, old or young, male or female, <strong>Montserrat</strong>ian or non-national.Figure ES6 shows that the underlying economic causes <strong>of</strong> poverty can be diverse. In <strong>Montserrat</strong>’s case,the most important are the spike in world market prices, its low natural resource base (especially since theeruptions) and the low demand on the island for goods and services. None <strong>of</strong> these are amenable to easysolutions.Economic issues are however not the only cause <strong>of</strong> poverty in <strong>Montserrat</strong>. Family breakdown, pressureson the carer parent to generate income as well as provide child care, domestic violence, unplannedpregnancies, drug and alcohol use, all play their part – and can lead to a cycle <strong>of</strong> continuing and intergenerationalpoverty from which it is very difficult for either parents or their children to escape.For other vulnerable groups, the issues are more fundamental. Their ability to work is limited for reasons<strong>of</strong> age, infirmity, disability or parental duties. They thus have to depend on family and friends, with14 Narayan D., Pritchett L. and Kapoor S., 2009, Moving out <strong>of</strong> Poverty: Success from the Bottom Up, World Bank/ PalgraveMacmillan15 Only a minority <strong>of</strong> households (most <strong>of</strong> which are those with older persons) have no one working implying thatlow wages allied to increased prices are more <strong>of</strong> an issue than unemployment per se.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES14

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>government and other organisations stepping in to assist those who are alone or whose families are unableor unwilling to support them. Direct assistance from government is however negligible meaning that thosewithout family support have to resort to one or more <strong>of</strong> the coping strategies described previously.Figure ES6. Economic Causes <strong>of</strong> PovertyLack <strong>of</strong> investment Depressed local orWorld↓ ↓due to poor security / international markets formarketperceived corruption.goods.pricesNatural disasters/Resource depletion.No/ limited naturalresourcesLow demand for jobs and goods.No jobsExploitation.Pr<strong>of</strong>iteering. Lack <strong>of</strong>labour laws/ tradeunionsHoarding.Inequitable terms<strong>of</strong> trade. HightaxationLack <strong>of</strong> skills No Work Low pay High pricesINSUFFICIENT INCOMENB. Items in larger font are considered to be those that apply most to <strong>Montserrat</strong>.Yet poverty is not just a question <strong>of</strong> income. Members <strong>of</strong> these vulnerable groups are also moresusceptible to some <strong>of</strong> the non-income aspects <strong>of</strong> wellbeing – loneliness, depression, vulnerability due toirregular support and absence <strong>of</strong> family members, and problems <strong>of</strong> housing and health care. By the sametoken the loss <strong>of</strong> wellbeing and social fragmentation and resulting psycho-social pressures resulting fromthe eruption are a long way from being healed.But these issues are not confined to vulnerable groups. Many <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians had to relocate following theeruption. Several <strong>of</strong> these still live in poor housing and are struggling with both the economic situation anda general feeling <strong>of</strong> vulnerability arising from their loss <strong>of</strong> houses, assets, income and family membersoverseas – over a third <strong>of</strong> households are single person. The psychological impact <strong>of</strong> the eruption stillcontinues and is likely to do so for years to come. In many PPAs, respondents referred to a loss <strong>of</strong>community spirit, mutual self help, togetherness – in short a loss <strong>of</strong> social capital - which exacerbatesproblems <strong>of</strong> economic hardship. In several cases, there is resentment towards migrants who are seen astaking jobs that should go to <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians. Conversely, for migrants, economic difficulties arecompounded by the view that their general wellbeing is adversely affected by having to pay more forhealth treatment, not being eligible for social welfare, bureaucratic issues related to work permits andimmigration requirements.Yet, by and large, the <strong>Montserrat</strong>ian population has a high standard <strong>of</strong> living in terms <strong>of</strong> consumer goods,a near universal availability <strong>of</strong> basic infrastructure, generally good housing conditions, and a very lowincidence <strong>of</strong> severe (food) poverty. In most cases therefore poverty on the island is largely due to theinability <strong>of</strong> current household incomes to keep up with the expenditures required to sustain current livingstandards rather than the absence <strong>of</strong> basic needs or severe unemployment – as is evident from the large<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES15

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>number <strong>of</strong> mentions <strong>of</strong> the words ‘struggling’ and ‘surviving’ in the PPAs. In this sense, the term hardshipis arguably more apposite in the <strong>Montserrat</strong>ian context than poverty.3.8 Changes since 2000Comparisons <strong>of</strong> the 2000 and 2008 PPAs reveal very similar results. This is not unsurprising given thatthey were both undertaken in periods <strong>of</strong> economic hardship. The factors causing these situations arehowever different. In 2000, the country was only beginning to recover from the eruptions while in 2008the economy was contracting due to the global recession and the completion <strong>of</strong> major constructionprojects. Both surveys are dominated by concerns about the high cost <strong>of</strong> living that has imposed a varyinglevel <strong>of</strong> hardship on a large proportion <strong>of</strong> the population. The coping strategies employed to enablepeople to ‘make ends meet’ are virtually identical as are the groups likely to be most vulnerable to severepoverty: the elderly, the mentally challenged and households with single headed families with children.There are however differences although these are a matter <strong>of</strong> degree rather than radical change. Inparticular, it is probable that the psychological impacts <strong>of</strong> the eruption have reduced, given that they arenow living in safe areas and considerable reconstruction has taken place. For instance, respondents arenow more concerned about improving current housing conditions than discussing the failings <strong>of</strong> the posteruptionshelter policy. If the sense <strong>of</strong> insecurity resulting from the eruption has, for many, decreased thisis partly <strong>of</strong>fset by an increase in insecurity resulting from increased immigration, especially during a time <strong>of</strong>economic stagnation. Issues related to unemployment and under-employment receive greater attention forthe same reason. Little attention was paid to migrant issues in 2000.Overall, responses received in the 2008 PPAs are more typical <strong>of</strong> those from other Eastern CaribbeanPPAs than those from 2000 16 . In the future, this is likely to be increasingly the case as memories <strong>of</strong><strong>Montserrat</strong>’s volcanic eruption fade to be increasingly replaced by the issues found in other CPAs –although they will be reawakened every time there is a spate <strong>of</strong> volcanic activity.4 The Institutional Analysis (IA) (Chapters 4 and 5)The objectives <strong>of</strong> the IA were to: (i) to identify the principal policies, programmes and activities relevant topoverty reduction; (ii) to assess the scope and effectiveness <strong>of</strong> these interventions; and hence (iii) toidentify potential recommendations as to how existing activities and can be improved and newinterventions introduced. The IA was undertaken through interviews and discussions with numerousgovernment, non-government and private sector organizations as well as the review <strong>of</strong> relevant documentsand statistics. The IA covered economic, infrastructure and social sectors. Suggestions arising from theIA, <strong>of</strong> which there were many, have been included in the CPA’s recommendations.16 Some <strong>of</strong> the differences may also be due to the different approaches in the two studies. The 2000 surveys wereundertaken just as the concept <strong>of</strong> PPA approach was gaining favour. At that time, poverty was still essentially seen inincome and quantitative terms; hence greater emphasis was given to exploring alternative definitions <strong>of</strong> poverty.Much <strong>of</strong> this is now the orthodoxy so more recent PPAs tend to stress the examination <strong>of</strong> the characteristics,concerns and needs <strong>of</strong> different sub-groups <strong>of</strong> the poor. This facilitates addressing the non-income aspects <strong>of</strong>poverty and deriving policy interventions for different vulnerable groups.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES16

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>4.1 Economic SectorsThe most important findings <strong>of</strong> the IA for the economic sectors are:There are no obvious opportunities for a rapid expansion <strong>of</strong> <strong>Montserrat</strong>’s economy, nor do anynew sectors with substantial job creation opportunities suggest themselves. This is not to saythat measures such as the re-introduction <strong>of</strong> the ferry to Antigua or the continued expansion <strong>of</strong>the nascent sand-mining industry would not be beneficial.The same goes for the establishment <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Montserrat</strong> Development Corporation and thecontinued implementation <strong>of</strong> the new centre at Little Bay. These are currently the maingovernment ‘economic initiatives’.The Department <strong>of</strong> Agriculture has several potential projects but these would benefit from amore detailed evaluation, which if positive, would increase the potential for funding.There are a number <strong>of</strong> schemes and incentives for small business. These incentives are thoughtto be well-known by the target users and have had some success 17 . Constraints are: (i) thereliance on grant funding - which might not be sustainable; and (ii) inadequate small businessrecord keeping.There is little demand for credit for new businesses due both to a low level <strong>of</strong> interest amongstthe population and the lack <strong>of</strong> obvious investment opportunities. The National DevelopmentFund has a substantial portfolio <strong>of</strong> outstanding loans. There is negligible NGO activity in terms<strong>of</strong> micro-credit or income generating activities.There is a demand for more, and better, vocational training, e.g. linked to apprenticeshipprogrammes, even if this tends to improve the employment prospects <strong>of</strong> new job seekerselsewhere than on the island itself.4.2 Health ServicesThe Ministry <strong>of</strong> Heath provides a range <strong>of</strong> primary, secondary and tertiary care services through 4 clinicsand one hospital. Health services had to be re-established since the eruption. Child health clinics are heldweekly at all health centres; there was 100% registration <strong>of</strong> children under 5 in the clinics with almost100% vaccination rates. Family planning clinics are held weekly. Virtually all births occurred at thehospital and are attended by trained health pr<strong>of</strong>essionals.The major concerns at present are the financing <strong>of</strong> health services and providing access to all. At present,treatment and consultations at the clinics are essentially free. Conversely, most residents pay for hospitalservices. These payments only cover a small proportion (under 10%) <strong>of</strong> the health budget and should thusbe seen as contributions rather than full cost fees. The main groups who do not pay are the elderly,children, the disabled and pregnant mothers; certain categories <strong>of</strong> civil servant are also exempt. Nonnationalsalso pay 1.5 to 2 times the fees <strong>of</strong> <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians.17 52 successful applicants in 2007 received grants between $1400 and $29,000 in agriculture, fishing, tourism,restaurants and printing; around 100 jobs were generated.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES17

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>Health costs are rising due to better, but more expensive treatments, people are living longer thusrequiring more treatment and costs associated with chronic diseases are disproportionately high 18 . At thesame time, the impact <strong>of</strong> sudden health expenditure on family incomes can be severe for those who are onlow incomes. It is anticipated that the new Health Strategy will address these issues with options beingconsidered including a National Health Insurance System, increased user charges, possibly allied toexemptions for some groups being subject to greater means testing.There are also issues related to the quality <strong>of</strong> health care in terms <strong>of</strong> the availability <strong>of</strong> trained nurses anddoctors and access to less frequently needed health services. This is largely attributable to the small size <strong>of</strong>the population, which <strong>of</strong>fers few opportunities for medical staff to gain a breadth <strong>of</strong> experience; thismakes the posts relatively unattractive. It also makes it harder to provide treatment for specialist problems,e.g. mental health.4.3 EducationPrimary and secondary education is compulsory up to age 16.government to all residents. Attendance is therefore almost 100%.Services are provided free by theGOM developed an Education in the Country Policy Plan for 1998-2002 in conjunction with DfID.Under this plan, the government is supporting initiatives in the areas <strong>of</strong> curriculum development, studentassessment and evaluation, pr<strong>of</strong>essional development for teachers, post-secondary education expansion,and educational infrastructure and information technology. Considerable progress has been made in thelast few years. One new day care centre opened and another was expanded in 2002, which made it possiblefor more children to access early childhood education at minimal cost. Access to primary education alsoincreased in 2002 with the addition <strong>of</strong> a fourth grade in one primary school; in 2005, two additional gradeswere included. The Government constructed <strong>Montserrat</strong> Community College (MCC) in 2004 where boththe secondary school and high school are located.With the construction and expansion <strong>of</strong> facilities, the Ministry is now turning its attention to issues relatingto the quality <strong>of</strong> education and services to disadvantaged pupils. The Ministry states that a number <strong>of</strong>children are underachieving; the truancy rate (over 50+ students every day) is also high. GOM alsoconsider that the behaviour <strong>of</strong> children is a key issue which adversely affects the educational attainment <strong>of</strong>other pupils and have introduced a red and yellow card system to caution students. Despite improvements,significant proportions <strong>of</strong> primary school students have below average reading levels. Some lessons aretoo academic for some students. Some parents 19 find it difficult to come to school to discuss the issues.Children arriving from non-English speaking countries have trouble integrating as do sometimes thosewho started their education in UK. To address these concerns, the government has introduced severalprogrammes (see Box ES1).18 Drugs for diabetics and hypertensives (c. 13% <strong>of</strong> the population) account for over half the cost <strong>of</strong> drugs providedfree.19 E.g. low income and non-nationals who find access harder due to lack <strong>of</strong> transport. These tend to be thehouseholds with problem kids.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES18

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>Box ES1: Targeted Educational Programmes• The Every Child Matters (ECM) agenda, under which the government wants every child to be healthy,safe, contribute positively to society, achieve - and enjoy achieving - economic well being.• School lunches for all students at a nominal fee.• The Pupil Support Unit (PSU) was formed less than a year ago to address disciplinary concerns in thesecondary school. The PSU is intended to provide counselling programmes and act as a resource unitproviding basic child guidance and a place to pacify children in a managed environment. However thePSU has yet to be fully established and engaging parents with ‘problem’ children is not straightforward.• A Change Manager has been employed to provide guidance on the changes needed in schools and howto bring these about to improve the quality <strong>of</strong> education and pastoral care in the secondary school.• The Low Achievers Education Programme is designed to provide extra lessons/ tuition to improve thebasic skills <strong>of</strong> some first year secondary school students in order that they can fully participate insecondary school classes.Overall however, the education system in <strong>Montserrat</strong> is generally working well. Reconstruction <strong>of</strong> facilitieshas largely been completed, although space is still limited and there are insufficient spaces for sports andrecreation. Attention is now turning to issues relating to the quality <strong>of</strong> education and support for thosewith educational needs and social problems, which have been exacerbated by the tight economic situationand the fragmentation <strong>of</strong> families.4.4 Social ServicesGovernment social welfare services are provided by the Social Welfare Department (SWD) andCommunity Services Department (CSD) within the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Health and Welfare. Together thesedepartments <strong>of</strong>fer a number <strong>of</strong> services to the poor and vulnerable including: regular and one <strong>of</strong>f socialassistance in cash or kind; counseling; fostering and adoption services.The Social Welfare System (SWS) provides regular financial assistance to very needy elderly, mentallychallenged and physically disabled <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians. Criteria are tight and. essentially only those with noother means <strong>of</strong> support receive SWS. Since 2001 GOM has also provided a rental subsidy for vulnerablegovernment housing tenants; again most <strong>of</strong> the recipients are elderly or disabled. In 2009, there were 270beneficiaries <strong>of</strong> SWS and just under 100 for the rental assistance scheme. SWS benefits (EC$600 permonth) are significantly higher than the indigence line but are well below the poverty line. One <strong>of</strong>f grantsfor emergency relief (food baskets, housing supplies, school uniforms) or medical care also provided (toaround 350 beneficiaries in 2008); criteria are very strict.Due to resource constraints, little assistance is available to poor family households who have been badlyaffected by falling incomes and rising prices. A recent review recommended that benefit levels should beraised and that eligibility should be more closely based on the needs <strong>of</strong> the applicant with less regard taken<strong>of</strong> other income sources <strong>of</strong> other household members. It was however recognised that the additionalfinance might prove difficult for this to be implemented. No recommendations were made to widen thecriteria to enable more non-elderly households to benefit.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES19

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>The SWD have also identified improvements that need to be made within their organisation, includingclearer eligibility criteria, more focussed targeting and consolidating the administration <strong>of</strong> the regular andone-<strong>of</strong>f programmes. Arguably, given budgetary constraints these should be the short term priorities.4.5 Social SecurityMandatory social security was introduced in <strong>Montserrat</strong> in 1986. At present around 2,100 employees and315 employers make contributions. Contributions are mandatory and collected from both employees andemployers. The scheme provides sickness and maternity benefits, invalidity assistance and old age/pension benefit. Self employed persons are expected to contribute 8% <strong>of</strong> their taxable income but noteveryone in this group contributes. In 2008, 570 persons received pensions, not all <strong>of</strong> whom will beresident on the island.The main current concerns are the level <strong>of</strong> the SS pension and the long term financial sustainability <strong>of</strong> thesystem. Proposals are included in the 2009 to address these issues including (i) gradually increasing theretirement age from 60 to 65 years; (ii) increasing the ceiling <strong>of</strong> the insured earnings to enable higherpensions to be paid; and (iii) index linking pension payments.4.6 The PoliceThe <strong>Montserrat</strong> Police Force is forward looking and has a number <strong>of</strong> programmes to address the socialaspects <strong>of</strong> criminal activity. These include training in domestic violence, child abuse, a community policinginitiative and close working relationships with other agencies (e.g. CSD, Education). Awareness campaignsare being run to combat domestic violence, child abuse and drug taking.4.7 HousingThe provision <strong>of</strong> public housing is the responsibility <strong>of</strong> the Ministry <strong>of</strong> Agriculture, Lands, Housing andthe Environment (MALHE). It has taken many years to address needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>Montserrat</strong>ians displaced by theeruption and remaining on the island. The situation is still not finally resolved with 70 families still living intemporary shelters and others in poor quality rented accommodation.Recent policy is for government to gradually get out <strong>of</strong> housing construction and leave it to the privatesector - but the private sector is slow to take up the challenge. Land is expensive and prices are increasingexacerbating the problem. It is also difficult for many to get a mortgage: assets were lost in the eruptionwhich led to non-payment <strong>of</strong> mortgages and consequently a poor credit rating.New initiatives are therefore being introduced. Grants have recently been re-introduced, for the first timehome owners who have sufficient funds <strong>of</strong> their own to construct a decent home within a 6-8 monthperiod but access to land and employment are required criteria. A more wide-ranging programme, HOME(Home Ownership Motivates Everyone) is included in the current budget and is designed to facilitateaccess to housing by people on low incomes and young pr<strong>of</strong>essionals.4.8 Physical InfrastructureThe provision <strong>of</strong> basic physical infrastructure in the safe zone is now largely complete. Water supply, roadaccess and electricity networks are essentially universal. In consequence, the focus is now more on<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES20

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>maintenance and extending networks to the few areas with inadequate service. Grants from CDB’s BNTFprogramme are being used for this purpose and to provide small scale community facilities.4.9 NGOsA number <strong>of</strong> NGOs (e.g. the Red Cross, the Old People’s Welfare Association, the Red Cross and thechurches) provide services to very poor individuals and families. There are also several immigrantassociations, most <strong>of</strong> which concentrate on providing advice and guidance, and putting on social andcultural activities. Two general comments can be made about these activities:the overall impression from the PPAs is that the services that these organisations provide arewelcomed by their beneficiaries.these organisations are operating on a shoestring through donations and voluntary services. Thelack <strong>of</strong> funds is therefore a major constraint on the extent <strong>of</strong> services that they can provide andtheir ability to cater for the current level <strong>of</strong> demand.In summary, the NGOs/ CBOS, know what they are doing, are doing the ‘right’ thing, but are unable toprovide the extent <strong>of</strong> assistance that they would like to. In this sense they are in a similar position to SWDand CSD whose operations are also heavily constrained by financial restrictions.4.10 OverviewThe scale <strong>of</strong> the destruction caused by the volcanic eruptions required the complete re-construction <strong>of</strong>social, physical and community infrastructure and systems in the safe zone. These programmes have beensuccessful in that basic infrastructure provision is now almost universal and social welfare, education andhealth services are all re-established.Attention is therefore shifting to issues related to the quality <strong>of</strong>, access to, and financing <strong>of</strong> these services.Most <strong>of</strong> these issues are already appreciated and policies and programmes to address them are beingimplemented, including several which are designed to directly benefit poor and vulnerable households.Several <strong>of</strong> these have been formulated or implemented in the last 12 months. Examples are social welfareservices and housing for the elderly and the disabled, education programmes for low achieving anddisruptive pupils, public awareness campaigns to address social issues such as drug-taking, antisocialbehaviour, domestic violence and child abuse. These initiatives are supplemented by a number <strong>of</strong> localNGOs, sometimes part-funded by overseas donors.The key issue is thus not so much one <strong>of</strong> an absence <strong>of</strong> relevant programmes but rather one <strong>of</strong> resourcing.In virtually every case, progress is hampered by insufficient funds and manpower. This situation has beenexacerbated by the current economic and fiscal contexts which have led to both an increasing demand forservices and are putting pressure on the funds available to address them.In this context, the way forward is to identify innovative approaches to these issues and to prioritisebetween the policies and programmes that have already been proposed in the MSDP and by theimplementing agencies concerned, <strong>of</strong>ten very recently. Given the likelihood that a significant increase infunds is unlikely in the short- or medium-terms, this puts a premium on identifying recommendations thateither do not have major financial implications or have the potential to attract donor funding.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES21

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>5 Poverty Reduction and the MDGs (Chapter 6)<strong>Montserrat</strong>, unlike some Caribbean countries has not produced its own MDGs. The following analysistherefore relates to 24 targets developed specifically for Caribbean countries; these Caribbean MDGs(CMDGs) are based around the global MDGs:1. The eradication <strong>of</strong> extreme poverty and hunger2. The achievement <strong>of</strong> universal primary education3. The promotion <strong>of</strong> gender equality and the empowerment <strong>of</strong> women4. The reduction <strong>of</strong> child mortality5. Improvement in maternal health6. Combating HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases7. Ensuring environmental sustainability8. The development <strong>of</strong> a global partnership for developmentThe CPA undertook an assessment <strong>of</strong> the progress <strong>Montserrat</strong> has made to the achievement <strong>of</strong> theCMDGs. The main findings were: <strong>Montserrat</strong> has achieved, or is well on the way to achieving, CMDGs 2, 4, 5 and 7.Goal 1 (reducing severe poverty and hunger) has been achieved in to the extent that the incidence<strong>of</strong> severe poverty is low – although the general poverty level remains high. Virtually all householdshave access to basic services.Goal 3 (empowering women) has been achieved in terms <strong>of</strong> education, partly achieved in terms <strong>of</strong>employment; issues <strong>of</strong> domestic violence are being tackled.Goal 7 has achieved its objectives in terms <strong>of</strong> the major diseases <strong>of</strong> poverty but now has toaddress those related to the NCDs, especially hypertension and diabetes – as do many Caribbean(and mom-Caribbean) countries.Goal 8 is not really applicable as its achievement largely depends on international rather thanGOM action.These findings are overwhelmingly positive. They nevertheless relate only to the CMDGs which do notaddress several <strong>of</strong> the issues raised in this report. Examples are: educational quality, migration and labourmarket issues, provision <strong>of</strong> welfare to the neediest, the care <strong>of</strong> the elderly, and social issues related t<strong>of</strong>amily break up and risky behaviour by teenagers and young adults. While not all <strong>of</strong> these are directlyrelated to income poverty, they are clearly important to reducing the non-income aspects <strong>of</strong> poverty andthe potential causes <strong>of</strong> future poverty. The CMDGs also do not address the issue <strong>of</strong> economic growth andemployment creation, which are <strong>of</strong> primary importance in reducing poverty – although as with Goal 8,GOM has little room for manoeuvre in this respect. The CMDGs should not therefore be seen asproviding a comprehensive framework for tackling poverty in <strong>Montserrat</strong>.<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES22

<strong>Montserrat</strong> <strong>Survey</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Living</strong> <strong>Conditions</strong><strong>Executive</strong> <strong>Summary</strong>6 The Poverty Action Programme (PAP) (Chapter 7)6.1 The PAP in the Context <strong>of</strong> the MSDPThe MSDP constitutes the island’s main statement <strong>of</strong> development policy. Although poverty reductiondoes not figure as one <strong>of</strong> its main strategic objectives, it is explicitly mentioned in relation to the expectedoutcomes <strong>of</strong> the Human Development strategic objective: “a reduction in the percentage <strong>of</strong> the population livingbelow the poverty line”. Furthermore, poverty reduction is seen as one <strong>of</strong> the outcomes <strong>of</strong> the drive to extendand diversify agricultural production and is implicit in the support to vulnerable groups inherent in several<strong>of</strong> the MSDP’s objectives and strategic actions; these address many <strong>of</strong> the issues raised in this study.Overall, the MSDP covers most <strong>of</strong> the topics and sectors that one would expect in a poverty reductionstrategy.Accordingly, there is little sense in the CPA preparing its own Poverty Reduction Strategy. The crucialquestion is therefore to devise a Poverty Action Programme (PAP) that can complement and reinforce theMSDP. This question was discussed at various junctures during the course <strong>of</strong> the study, as a result <strong>of</strong>which the following general principles have been adopted:The PAP should concentrate on those issues which have formed the basis <strong>of</strong> the CPA’s research,and should not attempt to replicate the comprehensive coverage <strong>of</strong> the MSDP.The PAP should concentrate on specific interventions (projects and programmes) rather thanmore general and all-embracing strategic policies (many <strong>of</strong> which also exist in ministerial anddepartmental strategy documents).The PAP should also identify any policy areas which have not been addressed in the MSDP.Within this context, the CPA’s recommendations address the generic objectives <strong>of</strong> any poverty reductionstrategy: (i) establishing a business-friendly environment to encourage private sector investment and hencejob creation; (ii) improve the provision <strong>of</strong> social and physical infrastructure needed to satisfy the basicneeds <strong>of</strong> the population; (iii) improve conditions for those currently in poverty and for whom employmentis not a realistic option, e.g. single parents, older persons and the disabled; and (iv) address issues thatthreaten to increase poverty in the future, e.g. the social issues related to risky and antisocial behaviour.Furthermore, the PAP should identify actions which are deemed to merit the highest priority because: (i)they are most urgently needed; and/or (ii) they can be achieved at relatively low cost; and/or (iii) they areimplementable within a relatively short time frame. Identifying priorities will also facilitate discussionswith donor agencies as to future loans and grants.Priority SectorsThe CPA’s research concentrated on the following sectors and priority areas, and these are the ones forwhich specific recommendations have been made: (i) economic issues; (ii) agriculture and fishing; (iii)housing and land; (iv) health; (v) education; social welfare; (vi) social issues; (vii) immigration; and (viii)governance and institutions.These sectors were those most frequently cited as priority concerns in the PPAs and the interviews carriedout as part <strong>of</strong> the Institutional Analysis. All are considered to <strong>of</strong>fer good potential for reducing poverty<strong>Montserrat</strong> Country Poverty Assessment, Final ReportHalcrow Group Limited, July 2012.ES23