Staffrider Vol.6 No.2 1985 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.6 No.2 1985 - DISA Staffrider Vol.6 No.2 1985 - DISA

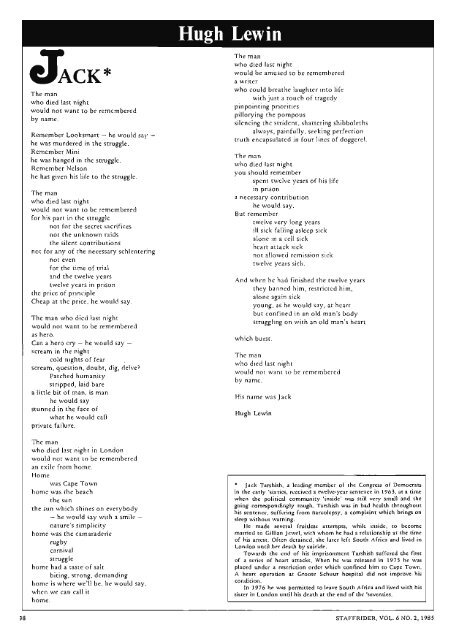

Hugh Lew intJ/ ACK*The manwho died last nightwould not want to be rememberedby name.Remember Looksmart — he would say —he was murdered in the struggle.Remember Minihe was hanged in the struggle.Remember Nelsonhe has given his life to the struggle.The manwho died last nightwould not want to be rememberedfor his part in the strugglenot for the secret sacrificesnot the unknown raidsthe silent contributionsnot for any of the necessary schlenteringnot evenfor the time of trialand the twelve yearstwelve years in prisonthe price of principle.Cheap at the price, he would say.The man who died last nightwould not want to be rememberedas hero.Can a hero cry — he would say —scream in the nightcold nights of fearscream, question, doubt, dig, delve?Patched humanitystripped, laid barea little bit of man, is manhe would saystunned in the face ofwhat he would callprivate failure.The manwho died last night in Londonwould not want to be rememberedan exile from home.Homewas Cape Townhome was the beachthe sunthe sun which shines on everybody— he would say with a smile —nature's simplicityhome was the camaraderierugbycarnivalstrugglehome had a taste of saltbiting, strong, demandinghome is where we'll be, he would say,when we can call ithome.The manwho died last nightwould be amused to be remembereda writerwho could breathe laughter into lifewith just a touch of tragedypinpointing prioritiespillorying the pompoussilencing the strident, shattering shibbolethsalways, painfully, seeking perfectiontruth encapsulated in four lines of doggerel.The manwho died last nightyou should rememberspent twelve years of his lifein prisona necessary contributionhe would say.But remembertwelve very long yearsill sick falling asleep sickalone in a cell sickheart attack sicknot allowed remission sicktwelve years sick.And when he had finished the twelve yearsthey banned him, restricted him,alone again sickyoung, as he would say, at heartbut confined in an old man's bodystruggling on with an old man's heartwhich burst.The manwho died last nightwould not want to be rememberedby name.His name was Jack.Hugh Lewin* Jack Tarshish, a leading member of the Congress of Democratsin the early 'sixties, received a twelve-year sentence in 1963, at a timewhen the political community 'inside' was still very small and thegoing correspondingly tough. Tarshish was in bad health throughouthis sentence, suffering from narcolepsy, a complaint which brings onsleep without warning.He made several fruitless attempts, while inside, to becomemarried to Gillian Jewel, with whom he had a relationship at the timeof his arrest. Often detained, she later left South Africa and lived inLondon until her death by suicide.Towards the end of his imprisonment Tarshish suffered the firstof a series of heart attacks. When he was released in 1975 he wasplaced under a restriction order which confined him to Cape Town.A heart operation at Groote Schuur hospital did not improve hiscondition.In 1976 he was permitted to leave South Africa and lived with hissister in London until his death at the end of the 'seventies.38 STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, 1985

At last year's Zimbabwe Book Fair Njabulo Ndebeie received the Noma Award for hisbook Fools, published by Ravan Press. Here is the full text of his acceptance speech.NOMA AWARD^ rnotograpns oy isiaay rartriage m* jm/kcektaace Sjkeeckby Njabulo S. NdebeieSometime after the notorious Land Act of 1913 was passedin the white South African Parliament, a Lands Commissionwas established to look into the effects of the legislation.This Act, it will be remembered, was the one responsible forthe granting of only 13 percent of land in South Africa toAfricans, while the rest was to be the domain of the whiteman. One of the most critical observers of this phenomenonas it was unfolding was Sol Plaatje, one of the major figuresin African writing in South Africa. His book, Native Life inSouth Africa (1916) is a landmark in the historiogrpahy onSouth African political repression. The book is remarkablenot only for its impressive detailing of facts but also for itswell considered rhetorical effects which express intelligentanalysis, political clarity, and a strong moral purpose.In his analysis of the Report of the Lands Commission,Sol Plaatje notes, among other observations, thatmwhile the ruling whites, on the one hand, contentthemselves with giving contradictory definitions oftheir cruelty the native sufferers, on the other, give nodefinitions of legislative phrases nor explanations ofdefinitions. All they give expression to is their bittersuffering under the operation of what in their experiencehas proved to be the most ruthless law that everdisgraced the white man's rule in British South Africa.(355-6)Plaatje's observation here is of very special interest to me. Hedocuments here one of the most debilitating effects ofoppression: the depriving of the oppressed of any meanigful,significant intellectual life. Because they no longer have aneffective hand in controlling history, they seem doomed torespond and seldom to initiate. Those doomed to respondseldom have the time to determine their real interests. Thatthe capability to initiate action has been taken out of theirhands implies also, that their ability to define has beendrastically reduced. Plaatje notes here, how the Africanoppressed appear to have been reduced to the status of beingmere bearers of witness. They do a good job of describingsuffering; but they cannot define its quality. The ability todefine is an intellectual capability more challenging, it seemsto me, than the capability to describe. For to define is tounderstand, while to describe is merely to observe. Beyondmere observation, the path towards definition will begin onlywith an intellectual interest in what to observe and how toobserve.It seems to me that a large part of the African resistanceto the evil of apartheid has, until recently, consisted of alargely descriptive documentation of suffering. And the bulkof the fiction, through an almost total concern with thepolitical theme has, in following this tradition, largelydocumented rather than explained. Not that the politicaltheme itself was not valid, on the contrary it is worthNjabulo Ndebeie, Noma Award winner reads from his bookFools to an attentive audience at last year'sZimbabwe Book Fair,exploring almost as a duty. It was the manner of itstreatment that became the subject of increasing dissatisfactionto me. Gradually, over a period of historical time, an imageemerged and consolidated, as a result, of people completelydestroyed, of passive people whose only reason for existingseemed to be to receive the sympathy of the world. Topromote such an image in whatever manner, especially ifsuch promotion also emanated from among the ranks of theoppressed themselves, was to promote a negation. It was topromote a fixed and unhistorical image with the result ofobscuring the existence of a fiercely energetic and complexdialectic in the progress of human history. There was, in thisattitude, a tragic denial of life.I came to the realization, mainly through the actualgrappling with the form of fiction, that our literature oughtto seek to move away from an easy pre-occupation withdemonstrating the obvious existence of oppression. It exists.The task is to explore how and why people can survive undersuch harsh conditions. The mechanisms of survival andresistance that the people have devised are many and farfrom simple. The task is to understand them, and then toactively make them the material subject of our imaginativeexplorations. We have given away too much of our real andimaginative lives to the oppressor and his deeds. The task isto give our lives and our minds to the unlimited inventivenessof the suffering masses, and to give formal ideologicallegitimacy to their aspirations.STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, 1985 39

- Page 2 and 3: NEW BOOKSFROM RAVANHis second autob

- Page 4 and 5: hoseby Bheki MasekoIllustrations by

- Page 6 and 7: Ihe teacher hadhardly dismissed us

- Page 8 and 9: That I had to run away from home wa

- Page 10 and 11: screaming his head off in his own s

- Page 12 and 13: Nikitinsky. He was sitting in a roo

- Page 14 and 15: Damian Garsidec9lukTo surpass the g

- Page 16 and 17: meeting we — the LiteMaster worke

- Page 18 and 19: or thirteenth of July we were all d

- Page 20 and 21: 'What do you want Johnny,' I saidin

- Page 22 and 23: I shrugged an embarrassed smile but

- Page 24 and 25: Andries W. OliphantT he Eye of the

- Page 26 and 27: orkingomenMabel was a garment worke

- Page 28 and 29: He was dedicated to his medicine,ye

- Page 30 and 31: 'You have two minutes.' The silence

- Page 32 and 33: Staf frider Popular HistoryMhala, t

- Page 34 and 35: Dombo RatshilumelaIn secret lepers

- Page 36 and 37: R regnancyf A poem should be palpab

- Page 38 and 39: one night in Meadowlands, another i

- Page 42 and 43: esources of living should constitut

- Page 44 and 45: SOUTH AFRICA: PASSPORT REFUSED TOSO

- Page 46 and 47: y Walt OyisiphoKaMtetwalood'What! I

- Page 48 and 49: TALKING STORYWhat this delayed reco

- Page 50 and 51: Andries W. Oliphant Lancelot Maseko

- Page 52: IN OUR NEXT ISSUEThami Mnyele, Dona

Hugh Lew intJ/ ACK*The manwho died last nightwould not want to be rememberedby name.Remember Looksmart — he would say —he was murdered in the struggle.Remember Minihe was hanged in the struggle.Remember Nelsonhe has given his life to the struggle.The manwho died last nightwould not want to be rememberedfor his part in the strugglenot for the secret sacrificesnot the unknown raidsthe silent contributionsnot for any of the necessary schlenteringnot evenfor the time of trialand the twelve yearstwelve years in prisonthe price of principle.Cheap at the price, he would say.The man who died last nightwould not want to be rememberedas hero.Can a hero cry — he would say —scream in the nightcold nights of fearscream, question, doubt, dig, delve?Patched humanitystripped, laid barea little bit of man, is manhe would saystunned in the face ofwhat he would callprivate failure.The manwho died last night in Londonwould not want to be rememberedan exile from home.Homewas Cape Townhome was the beachthe sunthe sun which shines on everybody— he would say with a smile —nature's simplicityhome was the camaraderierugbycarnivalstrugglehome had a taste of saltbiting, strong, demandinghome is where we'll be, he would say,when we can call ithome.The manwho died last nightwould be amused to be remembereda writerwho could breathe laughter into lifewith just a touch of tragedypinpointing prioritiespillorying the pompoussilencing the strident, shattering shibbolethsalways, painfully, seeking perfectiontruth encapsulated in four lines of doggerel.The manwho died last nightyou should rememberspent twelve years of his lifein prisona necessary contributionhe would say.But remembertwelve very long yearsill sick falling asleep sickalone in a cell sickheart attack sicknot allowed remission sicktwelve years sick.And when he had finished the twelve yearsthey banned him, restricted him,alone again sickyoung, as he would say, at heartbut confined in an old man's bodystruggling on with an old man's heartwhich burst.The manwho died last nightwould not want to be rememberedby name.His name was Jack.Hugh Lewin* Jack Tarshish, a leading member of the Congress of Democratsin the early 'sixties, received a twelve-year sentence in 1963, at a timewhen the political community 'inside' was still very small and thegoing correspondingly tough. Tarshish was in bad health throughouthis sentence, suffering from narcolepsy, a complaint which brings onsleep without warning.He made several fruitless attempts, while inside, to becomemarried to Gillian Jewel, with whom he had a relationship at the timeof his arrest. Often detained, she later left South Africa and lived inLondon until her death by suicide.Towards the end of his imprisonment Tarshish suffered the firstof a series of heart attacks. When he was released in 1975 he wasplaced under a restriction order which confined him to Cape Town.A heart operation at Groote Schuur hospital did not improve hiscondition.In 1976 he was permitted to leave South Africa and lived with hissister in London until his death at the end of the 'seventies.38 STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong>