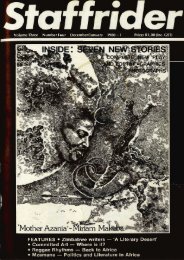

Staffrider Vol.6 No.2 1985 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.6 No.2 1985 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.6 No.2 1985 - DISA

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Nikitinsky. He was sitting in a roomupstairs, the old man was, and he wastaking three saddles to pieces: anEnglish one, a dragoon one, and aCossack one; and I stuck to his doorlike a burr, stuck there a whole hour,and all to no purpose. But then he casthis eyes my way.'What d'you want?' he asks.'A reckoning.''You've got designs on me?''I haven't got no designs, but I wantstraight out to .... 'Here he looked away and spread outon the floor some scarlet saddlecloths.They were brighter than the Tsar'sflags, those saddlecloths of his; and hestood on them, the little fellow, andstrutted about.'Freedom to the free,' he says to me,and struts about. 'I've tickled all yourmaternal parents, you Orthodox peasants.You can have your reckoningif you like; only don t you owe me atrifle, Matthew my friend?''He-he,' I answers. 'What a comicalfellow you are, and that's a fact! Seemsto me as it's you that owes me my pay.''Pay!' the master shoots out, and heknocks me down on my knees andshuffles his feet about and boxes me onthe ears for all the Father, Son, andHoly Ghost's worth. 'Your pay! Andhave you forgotten the yoke of mineyou smashed? Where's my ox-yoke?I'll let you have your yoke back,' Ianswer my master, and turn my simpleeyes upon him and kneel before him,bending lower than any earthly depth.'I'll give you your yoke back; onlydon't press me with the debts, oldfellow; just wait a bit.'And what d'you think, you Stavropolboys, comrades, fellow-countrymen, myown dear brethren? The market kept mehanging on like that with my debts forfive years. Five lost years I was like alost soul, till at last the year Eighteencame along to visit me, lost soul that Iwas. It came along on lively stallions, onits Kabardin horses, bringing along a bigtrain of wagons and all sorts of songs.Eh you, little year Eighteen, my sweetheart!Can it be that we shan't bewalking out with you any more, myown little drop of blood, my yearEighteen? We've been free with yoursongs and drunk up your wine and madeout your laws, and only yourchroniclers are left. Eh, my sweetheart!It's not the writers that rushed aboutover the Kuban those days, setting thesouls of generals free at a distance ofone pace. And Matthew son of Rodionwas lying in blood at Prikumsk at thattime, and there were only five versts ofthe last march left to the Lindino estate.Well, I went over alone, without thedetachment, and going up to the roomI went quietly in. The local powers wassitting there in the room upstairs.Nikitinsky was carrying round tea andbilling and cooing to them, but when hesaw me his face fell, and I took off myKuban hat to him.'Good day,' I says to the folks.'Accept my best regards. Receive avisitor, master; or how shall it bebetween us?''It's all going to be decent and quietbetween us,' answers one of the fellows:a surveyor, I notice by his way ofspeaking. 'It's all going to be quiet anddecent; but it looks as if you have beenriding a good way, Comrade Pavlichenko,for your face is all splashed with dirt.We, the local powers, dread such looks.Why is it?''It's because, you cold-blooded localpowers,' I answer, 'because in my looksone cheek has been burning for fiveyears — burning in the trenches, burningon the march, burning with a woman,will go on burning till the Last Judgement.The Last Judgement,' I say,looking at Nikitinsky cheerful-like; butby this time he's got no eyes, only ballsin the middle of his face, as if they hadrolled those balls down into positionunder his forehead. And he was blinkingat me with those glassy balls, alsocheerful-like, but very horrible.'Mat,' he says to me, 'we used toknow one another once upon a time,and now my wife, Nadezhda Vasilyevna,has lost her reason because of all thegoings on of these times. She used tobe very good to you, usen't she? Andyou, Mat, you used to respect her morethan all the others, and you don'tmean to say you wouldn't like to havea look at her now that she's lost thelight of reason?''All right,' I says, and we two go outinto another room, and there he beginsto touch my hands, first my right handand then my left.'Mat,' he says, 'are you my destinyor aren't you?''No,' I says, 'and cut that talk. Godhas left us, slaves that we are. Ourdestiny's no better than a turkey-cock,and our life's worth just about a copeck.So cut that talk and listen if you like toLenin's letter.''A letter to me, Nikitinsky?''To you,' I says, and takes out mybook of orders and opens it at a blankpage and reads, though I can't read tosave my life. 'In the name of thenation,' I read, 'and for the foundationof a nobler life in the future, I orderPavlichenko, Matthew, son of Rodion,to deprive certain people of life,according to his discretion.''There,' I says, 'that's Lenin's letterto you.'And he to me: 'No! No, Mat,' hesays; 'I know life has gone to pot andthat blood's cheap now in the ApostolicRussian Empire, but all the same, theblood due to you you'll get, andanyway you'll forget my look in death,so wouldn't it be better if I just showedyou a certain floor-board?''Show away,' I says. 'It might bebetter.'And again he and I went through alot of rooms and down into the winecellar,and there he pulled out a brickand found a casket behind the brick,and in the casket there were rings andnecklaces and decorations, and a holyimage done in pearls. He threw it to meand went into a sort of stupor.Jm. wasn't goingto shoot him. I didn't owehim a shot anyway, so I onlydragged him upstairs intothe parlour.'Yours,' he says, 'now you're themaster of the Nikitinsky image. Andnow, Mat, back to your lair at Prikumsk.'And then I took him by the bodyand by the throat and by the hair.'And what am I going to do aboutmy cheek?' I says. 'What's to be doneabout my cheek, kinsman?'And then he burst out laughing,much too loud, and didn't try to freehimself any more.'You jackal's conscience,' he says,not struggling any more. 'I'm talking toyou like an officer of the RussianEmpire, and you blackguards weresuckled by a she-wolf. Shoot me then,damned son of a bitch!'But I wasn't going to shoot him. Ididn't owe him a shot anyway, so Ionly dragged him upstairs into theparlour. There in the parlour wasNadezhda Vasilyevna clean off her head,with a drawn sabre in her hand, walkingabout and looking at herself in the glass.And when I dragged Nikitinsky into theparlour she ran and sat down in thearmchair. She had a velvet crown ontrimmed with feathers. She sat in thearmchair very brisk and alert andsaluted me with the sabre. Then Istamped on my master Nikitinsky,trampled on him for an hour or maybemore. And in that time I got to knowlife through and through. With shooting— I'll put it this way — with shootingyou only get rid of a chap. Shooting'sletting him off, and too damn easy foryourself. With shooting you'll neverget at the soul, to where it is in a felllowand how it shows itself. But I don'tspare myself, and I've more than oncetrampled an enemy for over an hour.You see, I want to get to know what lifereally is, what life's like down our way.010 STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong>