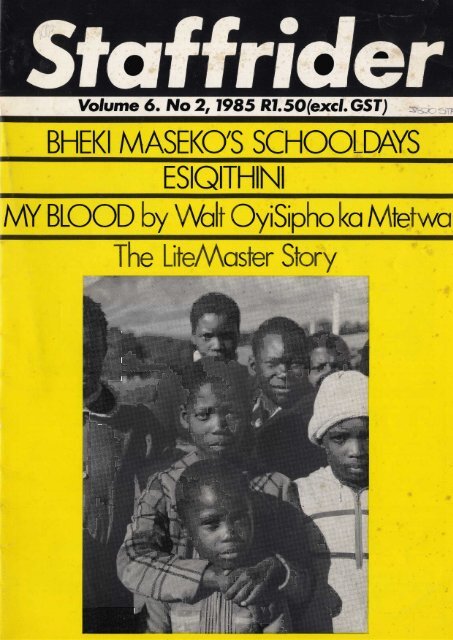

Staffrider Vol.6 No.2 1985 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.6 No.2 1985 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.6 No.2 1985 - DISA

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

NEW BOOKSFROM RAVANHis second autobiography, Afrika My Music, is set amidstthe tumultuous years of his return to South Africa after1976. 'Bantu Education' — the system which had forced himout of teaching and into exile when it was introduced in theFifties — had triggered the Soweto Revolt barely a monthbefore he returned to his native land after twenty years inEurope, Africa and the United States.R7.95¥H1 WOULD OPCANTHEMBAedrfecf by Essop Fate!1M i U!Es'kia MphahleleFATHER COME HOMEby Es'kia MphahleleIt is 1913, the year of the Natives' land Act. Thousands ofblack South Africans are driven off the land. The 'NativeReserves' where they are now supposed to live are mainlyarid, infertile, and overpopulated. Men flock in theirthousands to the mines and the cities in search of work,leaving their wives and children at home.Fourteen year old Maredi Tulamo from the village ofSedibeng faces life without his father, who has left home,as part of the pain and trauma of growing up. Restless and onthe threshold of manhood he sets out on a quest for themissing man. Alone and inexperienced, he is going down adangerous road ....Paperback R7.95 Hardback R11.50THE WORLD OF CAN THEMBAStaff rider Series No 18by Essop PatelCan Themba's understanding of the black townships ofJohannesburg was 'intuitive, complete and magical' in thewords of the publisher of Drum, the magazine in which muchof his work appeared. As the presiding spirit in 'The House ofTruth', as his Sophiatown matchbox was known, he wasunquestionably one of the most important South Africanwriters of the Fifties. The publication in one volume of awider selection of his work than has previously been available— poems, reportage, brief biographies and extendedanecdotes as well as the incomparable stories — is animportant literary milestone.R6.95FOOLS AND OTHER STORIES<strong>Staffrider</strong> Series No 19by Njabulo S NdebeleAFRIKA MY MUSICAn Authobiography 1957-1983by Es'kia MphahleleEs'kia Mphahlele's first work of autobiography, DownSecond Avenue, is one of the classics of African literature.After that seedtime came the years of exile during which —he was a 'listed' person — none of his works could be read inSouth Africa.'Fools', the title story in this collection, is a tale ofgenerations in the struggle against oppression. Zamani is amiddle-aged teacher who was once respected by thecommunity as a leader or the future. Then he disgracedhimself, and now he's haunted by the impotence of thispresent life. A chance meeting brings him up against Zani, ayoungs student activist whose attempts to kindle the flamesof resistance in Charterston Location are ludicrouslyimpractical. Both affection and hostility bind Zamani andZani together in an intense and unpredictable relationship.Finding each other means finding the common ground oftheir struggle. It also means re-examining their lives — and,notably, their relationships with women.R6.95

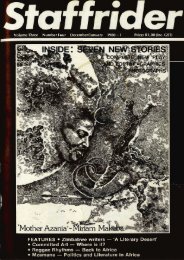

C 0 W T E W T SVolume 6. No 2,<strong>1985</strong>StoriesThose Were the Days by Bheki Maseko 2Runaway Recollections by Michael Goldberg 6The Life and Adventures of Matthew Pavlichenkoby Isaac Babel 9White Lies by Christopher Charles 17Grand Mai by Jan Esmond 23The Hill by G.M. Mogwe 33Go Away We're Asleep by J Makunga 35My Blood by Walt Oyi Sipho kaMtetwa 44PoemsiS.G.K., Roy Joseph Cotton 5Patrick FitzGerald 8Damian Garside, Elizabeth Villet, Thembeka Mbobo,Chris van Wyk 12Andries Oliphant, Thembeka Mbobo 22Farouk Stemmet 28Dombo Ratshilumela 32Kelwyn Sole, Cherry Clayton 34Norman Ramuswogwana Tshikovha 37Hugh Lewin 38Kelwyn Sole 41Andries Oliphant 43Keith Gottschalk, Hein Willemse, Evans Nkabinde ... 47Andries Oliphant, David Makgatho, Lancelot Maseko,Walt ka Mtetwa 48W © Q |l 11*1^ Q Editor: Chris van Wyk^ ^^^^ • %*• %^^^Front and back cover photographs: Paul AlbertsTalking Story by Mike Kirkwood 11 •The LiteMaster Story by Richard Ntuli 13 ^^^^^^^^^^i^^B^B^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^MWorking Women 24 <strong>Staffrider</strong> magazine is published by Ravan Press,Esiqithini by Jeff Peires 29 P. O. Box 31134, Braamfontein 2017, South Africa.Noma Award Acceptance Speech by Njabulo Ndebele . 39 (Street Address: 23 O'Reilly Road, Berea.) Copy-Index 42right is held by the individual contributors of allG. • material, including all graphic material, published inffH^fill^Qthe magazine. Anyone wishing to reproduce materialr^from the magazine in any form should appraoch theSusan Strachan 2,4 individual contributors c/o the publishers.Joanne Bloch 9 Printed by Galvin & Sales (Pty) Ltd., Cape Town.Gamakhulu Diniso 17 Layout and design by Mzwakhe Nhlabatsi forPercy Sedumedi 33, 35, 36, 44 The Graphic Equalizer.iRECENTLY UNBANNED.CALL ME NOT A MANMtutuzeli Matshoba, Ravan Press, 1979The stories of Mtutuzeli Matshoba, some of which were published in <strong>Staffrider</strong> have won himinstant respect from a wide range of readers. Matshoba s works cut open the nightmare ofsuffering and hatred with acutely chosen themes and a profoundly compassionate authorialpresence. The setting of the stories is Soweto after 1976. The ban imposed on this Ravanbestseller was lifted in March <strong>1985</strong>.STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong> 1

hoseby Bheki MasekoIllustrations by Susan Strachanere theWf''' 'tsBsmii'' '"''"' • • wlm,' JM& '•"'•'f|.W """" ~ — —/< 1~"~'" """ '-'•:: lifeUV-.- /, - W§&V / % %Jm§$^f\.M 5 \V^Jfe W L.^«w««^^- ~ . ~_ -%"""'"~"~ 1— „~~.~... 1f ft>^

quickly back to my place. When Ilooked back he gave me an 'I'll get you'look.When the bell rang that afternoon,I was among the first group at the door.But I got two stabs and a good punchon the head before I could get out.Winter was the most terrible season.There was a small stove in the centre ofthe classroom. Each pupil contributeda few cents or pieces of coal to keepthe fire burning. But the stove was toosmall to warm the whole class andbesides, most of the window-panes werebroken. Only the teachers and those infront enjoyed the heat. Although wetook turns in sitting at the front noteverybody got his share, due to thehigh number of the class.On Fridays we used to get rations ofa powder-like stuff called phuzamandla,a kind of porridge. It was served byolder boys in each class but Monde,young and diminutive as he was, wasone of the servers in our class.It was the survival of the strongestbecause one had to fight like mad tostay in the queue, and some went homewith empty mugs or tins. Monde's ilkusually took home a larger share thanmost. The teachers stayed aloof to avoidbeing pestered over a matter they couldnot solve.liBrhatata nevercame back after failing hisSub A. He became the bossof the Navarones gang.On Fridays we were dismissed earlierand the whole school would gather in anopen space in front of the classroomsfor prayers.One day, after our rations of phuzamandla,we assembled. Miss Masuku,the feared one, conducted the service.She told us in no uncertain terms to putour mugs and tins down before westarted praying.Reluctantly I placed my mug on theground and clutched it between myfeet, keeping a vigilant eye on Mondeand his friends. He was in the next row,pretending to be oblivious of mypresence. To accentuate his indifferencehe stood on his toes as if trying topeep over the shoulder of a tall guystanding before him. He always stoodbehind tall guys. Every day the teacherswould order him to stand at the front.But the next day he would be back tohis place at the back.I knew this tiny guy's presencemeant trouble. I was right because whenI opened my eyes after we had chantedamen, my mug was nearly empty. Andthere, between my mug and his feet,was the tell-tale trail of phuzamandla.So angry was I that I did not evenwait for the teacher to dismiss us. Igrabbed him- by the scruff of his shirtand seized the mug he was trying tokeep out of my reach behind him.Clinging to my shirt front with hisleft hand, he tried to get hold of themug I was holding up in the air with theother. The mug tipped, spilling thecontents which painted his face white.It was the intervention of Miss Masukuthat saved me from the gang's punchesthat had begun to rain on me.I did not need to do muchexplaining; the headmaster knew herregular visitors very well. They receivedmore cuts than I did.Bhatata never came back after failinghis Sub A. He became the boss of theNavarones gang, a position Monde &Company viewed with envy. Usually,during lunch or after school, (after theMunicipal police pass raiders hadpassed) the Navarones would prancedown the street past the school — theirhats pulled over their eyes and theirtrousers hanging low on their hips.Sometimes we found them smokinggrass at the shops. We would watch withenvy mixed with awesome fear. Butthey never bothered us — they had notime for small fish.In Standard One I made friends witha lanky fellow called Edward Masondo.I may attribute our friendship to thefact that we were both victims ofharassment. But most unfortunately, wetook different directions after schooland so could not share our fear.Edward was very fond of speakingEnglish whenever conversing with me. Ioften wonder how we communicated inthis foreign language because I couldnever distinguish English from Afrikaansthen. I usually identified Afrikaans withthe word 'doen' which was commonlyused in the text book. But it botheredme that I did not know who 'doen' was.At times I thought it was the boywearing a cap on the cover of the book.All the same we did communicate. Iwish now that I had had a tape recorder.Because of his small round face, thegang called Edward 'Babyface'. Hehated this name more than anythingelse which inspired them to intensifyits use. The fact that he was alwaysdressed formally might have added tohis vulnerability and their acts ofprovocation.I was called Gandaganda (tractor)because of my big feet. With my sister'sadvice I ignored them and this discouragedprovocation, but the namestuck. Later they modernized it toGandy.One day Edward brought his bicycleto school which in those days was very... Ilhe bike wasin the toilet. We found ithanging from therafters.uncommon. After school he was in for asurprise. The gang hung around hisbike like flies hang around a rottencarcass. Monde wanted a short ride —just a short one, while Killer sat on therear parcel carriage, holding on toEdward's neat blazer urging him tocycle on. Some threw awkward questionsat him while others rocked the bike. Hissmall face flushed, Edward was close totears.At last he got free after getting apowerful shove that nearly drove himinto a fence. I felt sorry for Edward butintervention would have been justinviting more molesting on my side.He brought his machine again thenext day and put it in front of theprincipal's office, chaining the backwheel to the frame of the bicycle.When the bell rang that afternoonmy joy for a promised short ridediminished when the gang entered mymind. I was so obsessed with the machineI had absolutely forgotten about them.To our utter surprise, the bike wasmissing. Edward's face reddened withanger.We tripped round the school yard,Edward leading the way. The gang kepta low profile, laughing openly now andthen.Eventually a good Samaritan told usthe bike was in the toilet. We found ithanging from the rafters. Edwardwanted to report the matter to theprincipal but quickly decided against it.He must have thought of the harassmenthe would be inviting. After all, Mondevisited the principal's office nearly everyday, but that did not change him. Theybid him farewell by throwing orangepeels at him.The next day he put the bicycle inthe same place, chaining it to the polethis time. When we knocked off, bothwheels were flat and the valves weremissing. He had no option but to wheelit home.'Babyface, why don't you ride yourbicycle?' ridiculed Monde, his lipstwisted into a smile of satisfaction.His face contorted in bitterness,Edward continued to wheel his squeakingmachine, casting an angry look time andagain at this pint sized guy wearingoversized trousers and a tie for a belt.Looking up at him with a mockingsmile, he adjusted his trousers now andthen.'You remind me of a teacher fromSTAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong> 3

Ihe teacher hadhardly dismissed us whenEdward gave him a hard onebetween die eyes, followed bya hot one from me.the farms, Babyface, the only differenceis that you wheel your bike instead ofriding it. Had it not been for Monde'sfriends, who roared with laughterbehind them, Edward would havestrangled him. He never brought thebicycle again.One day, just after lunch, a heavilybuilt woman clad in traditional Zuluattire and carrying two sticks, stormedinto the class. Mkhethwa followedtimidly close behind her.'Sa-wu-bo-na ma-ma!' we chanted asusual when an elder entered the classroom.But she ignored us and wentstraight to the teacher who was lookingstartlingly at the woman.'Where's the tsotsi who's provokingmy child?' demanded the woman glaringat our teacher.The teacher stared back in bafflement.T say where's the tsotsi who'sprovoking my child, can't you hear?'charged the woman pointing one stickat Mkhethwa and stamping the floorwith the other. 'My child is called thelion that sleeps in the dark forests ofAfrica right under your nose and youtell me that you don't know. Today hewas even robbed of his money forlunch.'Where's this tsotsi?' demanded thewoman turning to Mkhethwa whoquickly surveyed the room but couldnot locate Monde and Killer who hadtaken refuge beneath a bench.Someone must have informed theheadmaster for she entered the classroomand managed to cool the womandown. The culprits were hauled out,summoned to the office and punished.Among the Standard Twos there wasa stout guy with large ears andprotruding cheeks called Vincent. Hewas new at school and Monde must haveregretted his arrival because he playedrough, especially with the gang, whofeared him. The guys called him Vulture.He called Monde Mousy, usually inthe presence of the girls. AlthoughMonde hated this name he neveranswered back. With suppressed angerhe would only stretch his little mouthto its furthest, and eye Vincent withintense dislike. This indeed made Mondelook like a mouse.'I'm V.V.M. — Vincent VezokwakheMthombeni!' Vulture would boast,,

S. G. K.Roy Joseph CottonI've Heard the B Jhythm of Your Blood-FlowIMurungiYou who bear the name of Upright OneOh Straightforward Onewhy curse me with silence, my belovedyour love is the dying summerit has paled, discoloured and fallen.MurungiOh Straightforward Onewhy strike me with silence, my belovedyour eyes are the autumnwhich pales, discolours and falls.Oh Beloved Best Belovedyour silence is a rackupon which I liestretched out no moreunder you your thighswood-hard polished ebonyyour high cheeksyour eyesdivulging all secretsare stunning and alluringas the earth's most precious jewels.Murungiwhose father and father's brotherswore the oath of Batuniallegiance to Mau Mauwhose cousin Karega was torturedwhose cousin Karega was murderedwhose mother was violatedat the hand of Royalistsand you a small boy looked on.IIMurungi, Oh Belovedyou have returned to the land of your beginningand I have turned to mine.This my land is a strange, strange onethat prohibits me to love and know Afrikaas I have loved and known you.This land is a cruel cruel oneto pronounce our love a crime.Under your covers you asked of meCan it be so?I answeredYes it is so.On a night you asked of meWill not the Law of Nature triumph?Will men not be freeI answer Oh yes BelovedIt will be so.IllMurungi The Upright OneStraighforward OneYou are Afrika.I held you sensuous and languid in these my pale armsheard the rhythm of your blood-flowreceived your honey-sweetnessand you mine.Murungi'Man of Honourwhy punish me with silence?Know you not that I am bleedingtortured thoughts and limbs?You identify me with the oppressor?I am filthy Mzungu?The predator?Oh tear out my hearttoss it to hyenaslimbs to the lionthe sorcerer my soul.I am bewitched.S.G.K.OF irisoleaftwig hair,red straw inl\^*-l 3 L 1

That I had to run away from home waspreordained — astrologically infused inthe stars, the sun and the moon and theplanets. Destination Gillian's. I waseight years old and problems werealready packing in preponderously onmy weary shoulders. Problems both athome and abroad — even as far afield asthe exotic heady pastures of school.Father was preoccupied at work,wherever that was, and no longerafforded me the attention I deserved asfirst born and heir. Little brother waspresently indulging with abandon inassininely puerile pastimes, and stillbedwetting to boot. Mother was heavywith child, blossoming about in maternalblooms, totally oblivious of the treacheryshe was creating by undermining myrightful position as heir apparent — forthe second time.Five and six had been tough as hellin Grade One — starting big school andall. Seven years old in Grade Two hadbeen a breeze. In fact I could haveskipped Grade Two it had been so easy.Now eight in Standard One was provingto be just as traumatic as Grade One. Inever realised that the world was filledwith such happenings, such contemplations,such revelations. Everyone wasdoing so much! Everyone had done somuch! Their fathers and grandfathersand the rest of the paternal line, not tomention the maternals eternal — theyhad all been such busy bees makinghistory and now I had to learn all aboutit. What with double vowel sounds,some of which I was still a bit shakywith, Afrikaans, Arithmetic, etc. etc., Inow had to learn History as well! Itcould not be done! There surely werenot enough hours in the day! Limits tolife, learning and all.I had discussed it with Louis duringone cram session of spelling and we hadmade a pact to speak to the headmasterif the pressure hadn't let up by the endof winter. The seasons were mytimescale. The God-given vagaries of theweather fascinated and terrified me. Imean, winter was okay and all, but whatif God forgot (after all He had so much todo) and spring never came again?Anyway we were going to learn allabout the whys and wherefores of theweather in Standard Two — as if I didn'tby Michael GoldbergunawayecollectionsIllustratedwby Percy Sedumedire were theonly sweethearts in theclass, lovers in the true sense ofthe word. We once even played"Doctor Doctor".have enough on my plate already.Sultry summer at the beginning ofthe year had by way of some preconceiveddesign, given way to theautumnal tumbling of the leaves toclothe the earth in a multihued mantleof nature's fabric. Winter hit us one daywith her cold front from the Antarcticsomewhere and we huddled up in frontof the heater in the classroom with anew-found camaraderie. Man against theelements.Anyway Louis and I had thisarrangement to speak to our teacher'sboss when the first silkworm hatched inwhoever's silkworm box, it didn'tmatter — speak to him about the labourof learning at such a rate. In themeantime since the onset of winter,Louis was irritating me beyond belief.We shared a desk and he was constantlyrubbing his legs to keep himself warm.Rubbing, constantly rubbing, it didn'tmatter what subject we were learning.It wouldn't have been so bad, after allhe had a right to the personal maintenanceof his body temperature, butwith each forward thrust of his armsalong his thighs he bumped the undersideof the bench and then with each return,it jolted back to its former state of rest.For goodness sake, man, a boy hadtrouble enough learning real writing atthe best of times, but caligraphy underthese formidable conditions was a pipedream! I told the teacher so — I askedto be moved. Louis was seriouslyhampering my appreciation of herlearned ways — I told her.She laughed uncontrollably, almosthysterically for quite some time — astrange lady our teacher — and then shedemonstrated to the whole class a wayof rubbing your hands together topreserve your body temperature, withoutupsetting your desk.It was really quite tricky. What youhad to do was hold the palms of yourhands together, pointing your fingers tothe heavens as if you were praying forwarmer weather. Then, starting withyour right hand or your left, it didn'tmatter, you rubbed the one hand uppast the other, at the same time curlingthe fingers of the moving hand over theback of the fingers of the stationaryhand. Joint by joint — metacarpal bymatacarpal. Then the other handpushing upwards now, straightening thefingers of the first hand and curling overthe back of them in turn.Regretfully, Louis couldn't get themovement right. He was the only onein the class who couldn't do it. He didn'thave a motor co-ordination problem oranything — after all he was the only onein the class who could do a properheadstand and stay up for a minute anda half — but he just couldn't get thefinger friction concept right. I told himto practise at home. He did try, I knowit, his sister told me, but after a weekthe desk once again began to pursue itspath to peculiar performance. I hung onfor a day, but I couldn't stand it. Thistime we both went to the teacher toexplain our predicament. She laughedagain — hysterically — a strange lady ourteacher. Maybe all learned ladies laughedlike that. In the end Louis was allowedto wear his grey woollen gloves (theones his grandmother had knittedhim for Grade One, so they were a littletight now) whenever he felt the urge.Solutions to problems one at a time— painfully and patiently on.Gillian also asked to wear her gloves— being left-handed and at a decideddisadvantage when it came to fingerfriction,but the teacher stood by herLouis-only rule of gloves. I don't knowwhy. Gillian had this crazy pair ofgloves with each finger in a differentcolour which suited her fine, but theteacher was adamant.Gillian was my girl. We were the only6 STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong>

sweethearts in the class, lovers in thetrue sense of the word. We once evenplayed 'Doctor Doctor'. In short, wecraved each other. In fact, I was planningon running away from home tonight, toher lascivious embrace; it being Fridayand my problems at home aspiring toseemingly insurmountable proportions.Tonight was the night - I was goingto lay it on them in floods of fury.Learning, learning every day, I wassuffering in my scholarly pursuitsconstantly searching for the truth,without so much as the basics of supportany young man needed and deservedfrom his family. They were all to blamefor their lack of appreciation for what Iwas achieving. Father too quiet, littlebrother too noisy and mother too busybegetting unnecessarily a larger andlarger family. Hadn't she already hit thejackpot with me, I wanted to ask her.Tonight I was going to give them myManifesto for Family Union and supportand depending on their reaction, I wasgoing to stay or leave — the decisionbeing entirely of my own choosing.I had only this morning given Gillianthe pre-arranged signal. She was going todiscuss with her mother the possibilityof my moving in with them for a fewyears. After all, we were planning onmarrying in a few years time, definitelybefore high school, in any case, and theextra years afforded to us in living inclose proximity, possibly sharing thesame bedroom, would bode well forfuture marital bliss.I chose Gillian as my girl not onlybecause of the status of her being theonly left-handed person in the entireclass. I chose her the day she made, inmy mind anyway, somewhat of acelebrity of herself. Even at that ageshe was a staunch feminist with anactive independent mind. What happenedwas, during Arithmetic she asked theteacher if she could go to the cloakroom.The teacher refused. Arithmetic was herpet subject and she didn't like anyone inthe class to miss even a minute of it.Five minutes later Gillian asked again.She did it all beautifully and everything,following the correct procedure as laiddown by school etiquette and rules. Sheraised her hand, waited for the teacherto acknowledge the signal and thenasked once again in faultless English, ina respectful tone, if she could go to thecloakroom. She added that the visit wasbecoming desperately urgent and thatshe wouldn't be away more than twominutes at the utmost. Again theteacher declined the request.It was a summer's day, heavilyovercast with pent-up promises of rain.Suddenly the rain came gushing downand, in perverse synchronisation to thepittering and pattering on the windows,there formed under Gillian's bench agrowing puddle. The girl next to herstood up, screamed and pointed, botharms outstretched, at the offendingpool. Then we all stood up, one by one,boys and girls, peering in the designateddirection. There was a hushed stillnessabout the class, the only sound beingthe rhapsodic rancour of the rain. Andthen, puppetlike I raised my hands andbegan to clap. The whole class took upthe applause, slowly at first, softlyand in time, but growing in pace andintensity with each successive clap.Gillian stood up, performed a cutecurtsey, burst into tears and ran fromthe room, grasping her raincoat abouther.The next day we performed oursacred rite of love, Gillian and me. Eachholding onto a separate branch of thepoisonous oleander, at the entrance tothe school, we swore eternal faithfulness— the wayward to be damned tohell and struck down by all the poisonfrom that particular branch onto whichhe or she was holding. I noticed thatGillian's branch was smaller than mine,but it mattered not because she waslittler than me and I was sure that thepoison, even from the smaller shoot,would do the required job.At big break that day, fired by ournew-found love we set out to practiseheadstands, in a brave bid to smashLouis's one-and-a-half minute record.Love adds new qualities to life, butmore so for boys than for girls, I think.I discovered new dimensions to thetechnique of standing on my head thatday. Love imbued me with a new senseof balance, a clearer head, a moreperceptive mind, a heightened sensitivityfor the aesthetic.I broke the one-minute barrier andmy own record on my first attempt, butthen my neck, even though strengthenedby the ardour and lust coursing throughmy veins, gave way, and I collapsed overbackwards in a dishevelled heap oftriumph. Subsequent attempts, after alengthy rest, carried me well into thesecond minute and precariously close toLouis's amazing achievement.I managed one minute fifteeenseconds that day. Gillian was encouragementpersonified. She clapped, sheshouted, she did cartwheels, she evencomposed a special headstand war-crywhich attracted half the kids on the playground.Confidentially, I've alwaysplayed better with an audience at handand it was on my final try, withthousands of schoolchildren standingaround cheering, that my little body,inspired to greater strength, withstoodthe battering of time eternal, seventyfiveseconds in all on my head, beforefading on me.W• we went tothe boys' cloakroom — weagreed that it was the lesserof two evils, a girl in theboys' rather than a boy inthe girls'.Gillian was positively hopeless. Asgifted as she appeared to be, with thatnatural feline grace of the athlete, hertalents obviously did not extend as faras headstands. She tumbled truculentlytime and time again, cussing andthrowing her lithe little body around ina robustly morbid display of disequilibrium.Back in class she ran into a problemof paramount proportions. Throughoutheadstand training I had been wearingmy school cap which afforded me thatextra bit of balance, as well as protectionfrom the elemental nature of the playgroundgrass. Sadly Gillian had nottaken the same necessary precautions.Five minutes into mental arithmetic andshe began scratching assiduously at herscalp. The young lady next to her tooknote, stood up and screamed for thesecond time in two days, pointing thistime to a runaway red ant which haddive-bombed miraculously from Gillian'sscalp, to land next to her answer to thethird sum, which incidentally wasincorrect.Bravely Gillian raised her arm andasked to visit the cloakroom. This timeno explanation was necessary, theteacher assented immediately. I alsoraised my hand requesting to accompanyher. Teacher regarded me, a dazedexpression on her face, and noddednumbly.We went to the boys' cloakroom —we agreed that it was the lesser of twoevils, a girl in the boys' rather than aboy in the girls'. We scrubbed at her antinfestedhair for the better part of thelesson, combing out the offending interlopersand drying her off as best wecould with the lining of my blazer —there being no towels.We arrived back at class, Gillian'shair still dripping and my blazer sodden.Teacher grimaced at the sight of us andresumed the mental test which she hadheld over in our absence. We wonderedat the prophetic peculiarity of Gillianbeing twice wet in two days, oncebelow and once above. We meant toask the teacher after the school day, butshe surreptitiously beat a hasty retreatand vanished. We both scored top marksin the mental test, Gillian coming firstand myself a close second.Now some months later the scene forthe runaway was set. Mother fetchedGillian and me from school — the liftschemeof love. Little brother wasSTAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong> 7

screaming his head off in his own specialway in the back seat, so both Gillianand I crammed into the front seat.When we dropped Gillian off, Iperformed once again the pre-arrangedsignal, a subtle wink of the left and thenthe right eye. Almost not a wink, just alowering of the lid. She smiled inacknowledgement. The die was cast —she would speak to her mother rightaway.I worried that mother had perchancepicked up the runaway vibe, so on theway home I set about settling hersuspicions by introducing new conceptsto the car, such as percentages, aboutwhich I had heard some prefects talkingat break. I told her as a matter of factthat I had come top of the class andachieved the remarkable score of sevenpercent for the last spelling test. Motherfrowned. I had come tops, but I wasn'texactly sure about the percentage story.Still so very much to learn.After lunch and homework, twentyfivejumps on the trampoline andchecking to see if any silkworms hadhatched, I settled down to some heavymeditation. I had to prepare in my ownmind the sequence in which I was goingto confront the family with mylamentable list of grievances. I'd startwith the lesser evils, work my waythrough the mediums and then hit themwith the heavies at the end.S, "he told methat she had had one hell ofa time convincing her motherof the absolute necessity ofmy moving in.Father always came home a littlelater on Fridays, settled into hisfavourite chair and read the paper,watched TV and drank his ritual cup ofcoffee all at the same time. Multitalented.I approached the dinner tablewith nervous foreboding. Mother lit theSabbath candles and father said theprayers. I indulged in more than myusual drop of red wine to bolster myflagging resolve.I stood up ceremoniously.'I wanna talk about a few things,'I said with soft subtle dignity. No-onepaid any attention. Father was onceagain watching TV. Mother was servingup with fine precision. Little brotherwas racing his favourite Ferrari aroundhis soup plate, using crusts of bread todemarcate the course.'I wanna talk about a few things,'I said more loudly. Still no attention.This was no good — a radical route wasto be resorted to. I waited a momentand then yelled out my introductorysentence again, at the top of my voice.This time father did look at me brieflybefore turning back to the TV. Motherwas scolding little brother who waspouring his soup in lines over the whitetablecloth.I was still standing, stunned, numbedby my inability to play out my dramaas planned. Then in a fit of direfrustration and peeve I screamed at thetop of my voice. 'You don't love me!'I burst into tears and ran from theroom. I grabbed my knapsack, prepackedwith my travelling essentialsand hit out onto the road in flannelpyjamas and gown, heading for Gillian's.Flooding tears obscured my path.Tears salted with abandonment,exasperation, helplessness, hopelessness,disbelief, fraught with pain and fear,flowed to the ground. Suddenly theearth fell away from my feet and I washeaved higher and higher towards theheavenly abode of my Maker. Deathcomes so swiftly, so surreptitiously,stalking up and snatching at thesacrificial lamb.'Of course we love you,' shoutedfather above my dying dirge. He foldedme limply over his shoulder, my facesnuggling into the warmth of his back,bumping against him as he walkedback to the house. I howled for a whilelonger, the howl subsiding to a cry, aweep, a whimper. Then I relaxed andrelief overcame me. I was twice blessed.Snatched from the Gates of Heaven andreturned to the bosom of my lovingfamily — all in one shot.Gillian phoned just before bedtimeto confirm that everything was set ather end. She told me that she had hadone hell of a time convincing hermother of the absolute necessity of mymoving in. She had forced her mother'sirresolute hand by suggesting that shemight possibly be pregnant. That alwaysmanaged to get everyone 'shook up' inthe movies, she told me wryly. Hermother had become quite flustered, buthad finally acceded to her demands,on condition that they put the babyup for adoption.I explained to her that I had reevaluatedmy situation. I couldn'tleave them just yet I told her. It justwouldn't be right. They weren't quiteyet able to cope without me. Shewas bitterly disappointed, but sheunderstood.I went to bed wondering about theconcept of pregnancy. Wishing for thecoming of spring. Hoping for a newimproved family relationship of living,loving and working together. Worryingthat my silkworms would hatch beforethe mulberry leaves bloomed. Consideringthe necessity to purchase newmarbles for the forthcoming marbleseason. Working out a plan to get myfavourite smokey back from Louis. #PatrickFitzGeraldSong for BenBen you found methin as glassWoodstock in winterBen I found yourdrunken seminarin an Alex shebeenmidnight in Guguletuwatching for copsboot full of pamphletsModderdam roadthey bulldozed the shackwhere we met othersand plotted our victorydrinking brandyplaying Crazy Eightssinging Working Class Heroreading Leninwe brawled over the caryou dented at 'bush'but you always had planswere always full of places and peopleBen I miss youyou always knewthe blood-roads aheadyour project oftaming the gangsturned their angeragainst the systemsecond time around(what went wrong?)they struck you downin Cape TownBen Louw is deadI hear the newsacross a thousand milesof exileand I hear your voice, back in '77calm in an argument's heat,reminding us of thosewho have left and who returnmay the freedom songs sungbeside your graveecho and re-echoand make us bravemay the earth around your deathrich with your memorybring forth a dark redwine of freedomPatrick FitzGerald8 STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong>

The LifeandAdventuresof/MatthewPavlichenkoby Isaac BabelComrades, countrymen, my own dearbrethren! In the name of all mankindlearn the story of the Red General,Matthew Pavlichenko. He used to be aherdsman, that general did — theherdsman on the Lidino estate, workingfor Nikitinsky the master and lookingafter the master's pigs till life broughtstripes to his shoulder straps; and withthose stripes, Mat began to look afterthe horned cattle. And who knows, ifthis Mat of ours had been born inAustralia he might have risen toelephants, he'd have come to grazingelephants; only the trouble is, I don'tknow where they'd be found in ourStavropol district. I'll tell you straight,there isn't an animal bigger than thebuffalo in the whole of our wide region.And a poor lad wouldn't get no comfortout of buffaloes: it isn't any fun for aRussian fellow just getting a laugh outof buffaloes! Give us poor orphanssomething in the way of a horse forkeeps — a horse, so as its mind and ribscan work themselves out at the far endof the fields.And so I look after my horned cattle,with cows all around me, soaked in milkand stinking of it like a sliced udder.Young bulls walk around me — mousegreyyoung bulls. Open space around mein the fields, the grass rustling throughall the world, the sky above my headlike an accordion with lots of keyboards— and the skies in the Stavropol districtare very blue, boys. Well, I looked aftermy cattle like this, and as there wasnothing to do, I used to play with thewinds on reeds, till an old gaffer says tome:'Matthew,' says he, 'go and seeNastasya.''Why?' says I. 'Or maybe you'rekidding me.''Go,' he says, 'she wants you.'And so I goes.'Nastasya,' I says, and blush black inthe face. 'Nastasya,' I says; 'or maybeyou're kidding me.'She won't hear me out, though,but runs off from me and goes onrunning till she can run no more; andI runs along with her till we get to thecommon, dead-beat and red and puffed.7o xhy did youhang your nead, Matthew, orhang was it your some ne notion or otherthat was heavy on yourheart?'Matthew,' says Nastasya to me then,'three Sundays ago, when the springfishing was on and the fishermen weregoing down to the river, you too wentwith them, and hung your head. WhyIllustrated by Joanne Blochdid you hang your head, Matthew, orwas it some notion or other that washeavy on your heart? Tell me.'And I answer her'Nastasya,' I says, 'I've nothing totell you. My head isn't a rifle and thereain't no sight on it nor no backsightneither. As for my heart — you knowwhat it's like, Nastasya; there isn'tnothing in it, it's just milky, I dare say.It's terrible how I smell of milk.'But Nastasya, I see, is fair tickled atmy words.'I'll swear by the Cross,' she says, andbursts out laughing with all her mightover the whole steppe, just as if she wasbeating the drum, 'I'll swear by theCross that you make eyes at the youngladies.'And when we'd talked a lot ofnonsense for a while we soon gotmarried, and Nastasya and I startedliving together for all we was worth, andthat was a good deal. We was hot allnight; we was hot in winter, and allnight long we went naked, rubbing ourraw hides. We lived damn well, right ontill up comes the old 'un to me a secondtime.'Matthew,' he says, 'the masterfondled your wife here there andeverywhere, not long since. He'll get herall right, will the master.'And I:'No,' I says, 'if you'll excuse me, old'un. Or if he does I'll nail you to thespot.'So naturally the old chap makeshimself scarce. And I did twenty verstson foot that day, covered a good pieceof ground, and in the evening I got tothe Lidino estate, to my merry masterSTAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong> 9

Nikitinsky. He was sitting in a roomupstairs, the old man was, and he wastaking three saddles to pieces: anEnglish one, a dragoon one, and aCossack one; and I stuck to his doorlike a burr, stuck there a whole hour,and all to no purpose. But then he casthis eyes my way.'What d'you want?' he asks.'A reckoning.''You've got designs on me?''I haven't got no designs, but I wantstraight out to .... 'Here he looked away and spread outon the floor some scarlet saddlecloths.They were brighter than the Tsar'sflags, those saddlecloths of his; and hestood on them, the little fellow, andstrutted about.'Freedom to the free,' he says to me,and struts about. 'I've tickled all yourmaternal parents, you Orthodox peasants.You can have your reckoningif you like; only don t you owe me atrifle, Matthew my friend?''He-he,' I answers. 'What a comicalfellow you are, and that's a fact! Seemsto me as it's you that owes me my pay.''Pay!' the master shoots out, and heknocks me down on my knees andshuffles his feet about and boxes me onthe ears for all the Father, Son, andHoly Ghost's worth. 'Your pay! Andhave you forgotten the yoke of mineyou smashed? Where's my ox-yoke?I'll let you have your yoke back,' Ianswer my master, and turn my simpleeyes upon him and kneel before him,bending lower than any earthly depth.'I'll give you your yoke back; onlydon't press me with the debts, oldfellow; just wait a bit.'And what d'you think, you Stavropolboys, comrades, fellow-countrymen, myown dear brethren? The market kept mehanging on like that with my debts forfive years. Five lost years I was like alost soul, till at last the year Eighteencame along to visit me, lost soul that Iwas. It came along on lively stallions, onits Kabardin horses, bringing along a bigtrain of wagons and all sorts of songs.Eh you, little year Eighteen, my sweetheart!Can it be that we shan't bewalking out with you any more, myown little drop of blood, my yearEighteen? We've been free with yoursongs and drunk up your wine and madeout your laws, and only yourchroniclers are left. Eh, my sweetheart!It's not the writers that rushed aboutover the Kuban those days, setting thesouls of generals free at a distance ofone pace. And Matthew son of Rodionwas lying in blood at Prikumsk at thattime, and there were only five versts ofthe last march left to the Lindino estate.Well, I went over alone, without thedetachment, and going up to the roomI went quietly in. The local powers wassitting there in the room upstairs.Nikitinsky was carrying round tea andbilling and cooing to them, but when hesaw me his face fell, and I took off myKuban hat to him.'Good day,' I says to the folks.'Accept my best regards. Receive avisitor, master; or how shall it bebetween us?''It's all going to be decent and quietbetween us,' answers one of the fellows:a surveyor, I notice by his way ofspeaking. 'It's all going to be quiet anddecent; but it looks as if you have beenriding a good way, Comrade Pavlichenko,for your face is all splashed with dirt.We, the local powers, dread such looks.Why is it?''It's because, you cold-blooded localpowers,' I answer, 'because in my looksone cheek has been burning for fiveyears — burning in the trenches, burningon the march, burning with a woman,will go on burning till the Last Judgement.The Last Judgement,' I say,looking at Nikitinsky cheerful-like; butby this time he's got no eyes, only ballsin the middle of his face, as if they hadrolled those balls down into positionunder his forehead. And he was blinkingat me with those glassy balls, alsocheerful-like, but very horrible.'Mat,' he says to me, 'we used toknow one another once upon a time,and now my wife, Nadezhda Vasilyevna,has lost her reason because of all thegoings on of these times. She used tobe very good to you, usen't she? Andyou, Mat, you used to respect her morethan all the others, and you don'tmean to say you wouldn't like to havea look at her now that she's lost thelight of reason?''All right,' I says, and we two go outinto another room, and there he beginsto touch my hands, first my right handand then my left.'Mat,' he says, 'are you my destinyor aren't you?''No,' I says, 'and cut that talk. Godhas left us, slaves that we are. Ourdestiny's no better than a turkey-cock,and our life's worth just about a copeck.So cut that talk and listen if you like toLenin's letter.''A letter to me, Nikitinsky?''To you,' I says, and takes out mybook of orders and opens it at a blankpage and reads, though I can't read tosave my life. 'In the name of thenation,' I read, 'and for the foundationof a nobler life in the future, I orderPavlichenko, Matthew, son of Rodion,to deprive certain people of life,according to his discretion.''There,' I says, 'that's Lenin's letterto you.'And he to me: 'No! No, Mat,' hesays; 'I know life has gone to pot andthat blood's cheap now in the ApostolicRussian Empire, but all the same, theblood due to you you'll get, andanyway you'll forget my look in death,so wouldn't it be better if I just showedyou a certain floor-board?''Show away,' I says. 'It might bebetter.'And again he and I went through alot of rooms and down into the winecellar,and there he pulled out a brickand found a casket behind the brick,and in the casket there were rings andnecklaces and decorations, and a holyimage done in pearls. He threw it to meand went into a sort of stupor.Jm. wasn't goingto shoot him. I didn't owehim a shot anyway, so I onlydragged him upstairs intothe parlour.'Yours,' he says, 'now you're themaster of the Nikitinsky image. Andnow, Mat, back to your lair at Prikumsk.'And then I took him by the bodyand by the throat and by the hair.'And what am I going to do aboutmy cheek?' I says. 'What's to be doneabout my cheek, kinsman?'And then he burst out laughing,much too loud, and didn't try to freehimself any more.'You jackal's conscience,' he says,not struggling any more. 'I'm talking toyou like an officer of the RussianEmpire, and you blackguards weresuckled by a she-wolf. Shoot me then,damned son of a bitch!'But I wasn't going to shoot him. Ididn't owe him a shot anyway, so Ionly dragged him upstairs into theparlour. There in the parlour wasNadezhda Vasilyevna clean off her head,with a drawn sabre in her hand, walkingabout and looking at herself in the glass.And when I dragged Nikitinsky into theparlour she ran and sat down in thearmchair. She had a velvet crown ontrimmed with feathers. She sat in thearmchair very brisk and alert andsaluted me with the sabre. Then Istamped on my master Nikitinsky,trampled on him for an hour or maybemore. And in that time I got to knowlife through and through. With shooting— I'll put it this way — with shootingyou only get rid of a chap. Shooting'sletting him off, and too damn easy foryourself. With shooting you'll neverget at the soul, to where it is in a felllowand how it shows itself. But I don'tspare myself, and I've more than oncetrampled an enemy for over an hour.You see, I want to get to know what lifereally is, what life's like down our way.010 STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong>

TALKING STORYA <strong>Staffrider</strong> feature in which writers andcritics discuss storytellers and their work.In this issue MIKE KIRKWOOD writes aboutIsaac Babel's 'The Life and Adventures ofMatthew Pavlichenko'.'You are my old master, you have had the command longenough, now I am your master' — said the slave Maurits vanMauritius to Cornelis Coetze one day in the year 1800, ona lonely farm in the Roggeveld, moments before he beat hisold master's brains out with a crowbar. No doubt words andblows to the same effect had been meted out before. Nodoubt they would be again. Nor have we outlived the dreamof the rising and the retribution. Sometimes it seems toparalyse us, culturally speaking. Obsessively contemplatingthe moment of apocalypse, the dawn of liberation and thenew society, few of our writers have been able to create thescene between Maurits and Cornelis — in all its variations —with any conviction. Perhaps Babel's version of Nemesis, setin the Russian revolutionary period, has something to teachus.Its author had, of course, one great advantage. Born inOdessa in 1896, Isaac Babel had lived through the Russianrevolution — Matthew Pavlichenko's 'little year Eighteen, mysweetheart' — when he came to write this story. Afterwards,he joined Budyonny's Cossack cavalry for the Polishcampaign of 1920. The ani-Semitism of the Cossacks (Babelwas Jewish, and so were many of the Polish civilians in thecommunities ravaged by the war) and their reckless, pulsatilephysicality (Babel was slightly built, wore glasses, and didn'tride well) made his decision to enlist with them remarkable.A number of the resulting stories (published in English asCollected Stories in the Penguin Modern Classics) turn on themixed feelings the Cossacks have about him, and on his needto find some measure of acceptance among them if he isgoing to get to grips with his subject. (One thinks ofMtutuzeli Matshoba among the migrant workers, of NjabuloNdebele or Mbulelo Mzamane and the street gangs that figurein their stories of childhood.)In deliberately seeking out experience which can beshared, and actively identifying himself with his 'material'in order to allow it to speak and tell, Babel was choosing togo down the old road of that 'timeless tradition of storytelling'mentioned by Njabulo Ndebele when he introducedthe Turkish 'teller', Yashar Kemal, in our last issue. (Washe also choosing the 'road' of the story rather than the 'map'of the novel, a mode of fiction which establishes a qualitativelydifferent connection with experience?) Other attributes ofthe storyteller stand out in him too — more than this briefarticle can hope to itemize — but this one may merit specialnotice because it touches on a theme implicit in the <strong>Staffrider</strong>literary project from the beginning: the nature of'committed' writing. I believe that the more one considersthe possibility of storytelling in the contemporary world (the'global' as opposed to the 'organic' village, perhaps) the moreone is driven to conclude that it is the method which declaresthe committed writer rather than the subject addressed. It ishow we allow a subject to speak rather than what we make itsay that ensures its accessibility to a participant rather than areflective readership.The Long and the Short of ItAs with oral storytellers, so with the writers there are thosewho like to spin it out (another great Russian, Leskov, islike this) and those who like to cut it to the bone. Babel isdefinitely in the latter category. In this story it is not onlythe life of Pavlichenko which is anatomized in deft, seeminglycareless strokes: the ancient and modern history of ruralRussia are compacted into his few pages, together withthe political economy of the landowner's estate. Babel's-striking ability to select the most telling 'moments' in hisstory is part of this. So is the sharply focused, emblematicway in which he depicts the physical world — from the wildenergy of the horses working out 'at the far end of the fields',beloved of the peasants, to the scarlet saddle cloths 'brighterthan the Tsar's flags' on which the master 'strutted about'.Both of these skills in the writer draw on oral storytelling.The shifts in the story happen quite naturally within thenarrative style which Pavlichenko uses — a style which, oneimagines, Babel had often encountered among the Cossackshe campaigned with. This talent for laconic compression, forleaving out what it is not necessary to say, is imbedded inpeasant speech. ' "Nastasya," I says; "or maybe you^rekidding me." ' This is the style of love declarations downStavropol way.Similarly, in creating an emblematic physical worldBabel stays within the limited field of vision of his storyteller,but explores the resources of peasant experience andspoken idiom to bring out the full significance of ordinarythings. Thus Pavlichenko describes himself as being 'soakedin milk and stinking of it like a sliced udder' and then tellsNastasya that his heart is 'just milky, I dare say. It's terriblehow I smell of milk.'Pavlichenko the StorytellerIn some of his stories — like this one — Babel creates a storytellerfigure within the tale. More than this, he creates acommunity of readers-, people who, like the village audiencein the oral tradition, have something to gain from theirparticipation in the storytelling. They gain in entertainment,certainly; also by way of what Walter Benjamin 1 calls'counsel' — the kind of wisdom that can be put to use inone's own life. About counsel Benjamin remarks that 'it isless an answer to a question than a proposal concerning thecontinuation of a story which is just unfolding. To seek thiscounsel one would first have to be able to tell the story.(Quite apart from the fact that a man is receptive to counselonly to the extent that he allows his situation to speak.)'Compare this with Ndebele's formulation in our last issue:' . . . the reader's emotional involvement in a well-told storytriggers off an imaginative participation in which the readerrecreates the story in his own mind, and is thus led to drawconclusions about the meaning of the story from theengaging logic of events as they are acted out in the story.'The first community of readers suggested by the story isthat of the Cossack revolutionary soldiers immediatelyaddressed by Pavlichenko, a community of which Babel hadfirst-hand experience and which, as we have seen, played avital role in the generation of his work. A further, or underlyingcommunity is glimpsed in the narrator's references to'our Stavropol district' from which this Cossack generalcomes. It is also worth noting that the storyteller is firstidentified as someone from both these communities who isfamiliar with the story of Pavlichenko's life. It is only at thebeginning of the second paragraph, in one of those surprisestrokes through which the story is impelled forward (and thereader/listener's pleasure considerably enhanced) that wediscover Pavlichenko himself to be the narrator.STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong> 11

Damian Garsidec9lukTo surpass the grandmastersOne must not just deprive themBut denude their inheritance.One must crawl in under the skinOf landscape — wriggle inBeneath the rough hide.Let your little incisorsBite through the fat, the uppermost crustWith its bosveld and koppiesAnd camouflage stuff.Cleave a path for your bodyThrough its neutrals and sombresTo that soft underbellyBe nourished and sluk.Pertinent devilsNothing is neutral nowThere are rivers of heartbloodThere are rivers to cross.Past grainfields of labour and dorpiesOf lawTo that mythical homelandWhere the mountains shout down'Dig as you crawlThere is blood enoughSluk.'Damian GarsideElizabeth VilletA•his citythere is a momentin this citywhen the eyes of the cityare closedand the mountain's body sleeps —even the newspaper boysare curled under their light coveringsin cornerslike caterpillars in dried leaf cocoonswaiting to emergewith newsprint wingsand the city waits to dream . . .there is a moment in this citywhen the city lies defencelessas a sleeping childthat can't be harmed —a moment between the breath inand the breath out —a moment in this city1 of my waiting breathless heartElizabeth VilletTembeka Mbobo-yUntitledambivalence is a wordthat cannot explainmy inertia.Stagnation is a pitand failing to seethe dying fires isno excuse.Hell is sort-of-comfortable,but basically rotten.I've seen and felt it —all my life.^ ^O, .,Wf widowsand orphansblack veils and ragsstrength and unitytears and laughterthe presence of an absence.windowless housesand gateless fencesbleak futures andinevitable departuresthe resonant sound ofthe knock that never comes.lunch packs without lunchesand coalboxes without coalwarm donations andendless thank yousthe echoes of laughterthat once was.permeating happinessand eerie forgetfulnessdays of chips andrays of sunshinethe presence of a newsemi-unknown and semi-wanted.white veils and velvets andlaces and flowerslaughter and tearsthe presence of knocks andhappiness and anger andhateful regrets.| |lintidedChained to womanhoodI couldn't fight nor try nor win— they thought.Unsupported I should falland rise and fall— they perceived.Insecured I would calland cry and beg— they assumed.Deserted I couldn't mendand build and— spread growth.They didn't know me . . .They may have thoughtI was just —awQman!IIlector P.It could have been anywherebut it was hereIt could have been anybodybut it was youIt could have happened anywaybut it was this wayIt could have been due to anythingbut it was thisIt could have stopped anythingbut it was youMaybe it could not be helpedby us unwary mortalsIt was never plannedbut by the jittery handsof a few . . .We remembered you againyesterday.IIwn titledI buried it in ashallow gravesomehow expectingrains to open it upthat i might geta glimpse of itagain.Chris van WykTXHE REASON,The reason whymurderers and thievesso easilybecome statuesare made into monumentsisalready their eyes are granitetheir heartsare madeof stoneChris van Wyk12 STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong>

The I 1 ^Photographs by David JoosteBMby Richard Kichard NtuliiteMasterIntroduction and interviews byJon Lewis and Mark SwillingINTRODUCTIONFor over a year 130 MAWU members dismissed fromLiteMaster in Wadeville have been meeting three times perweek at Morena Store, Katlehong, waiting for the results of acourt case which will decide their fate. These regular meetingsmaintain the workers' morale and solidarity. They alsoprovide education. The tactics of the employer and questionsof trade union organisation are debated in detail. Thesemeetings are highly disciplined and structured — peoplespeak only through the chairperson. At the same time allmembers are encouraged to participate. The debates areinterspersed with song.Richard Ntuli's story was a collective effort. Although heprovided the main narrative his story was constantlycorrected and added to by other members. Richard Ntuli wasthe first chairperson of the first shop steward council set upon the East Rand in 1981.PHINEAS TOLO: I started working for LiteMaster on 13 May1954 — making score (doing piece work). The score was toohigh to reach. We were under pressure every day. There wasno time to go anywhere. I worked so hard — until my fingerswere bleeding and painful. The basic wage was R6.93 perweek. Working 7.00 a.m. till 7.00 p.m. and Saturday 7.00 a.m.till 4.00 p.m. you could earn R9 to Rll.I joined MAWU on 7 March 1981. Before the union cameworkers had no power. There were no strikes. If you talked,if you were late, if you mentioned wages, if you didn't makethe score — then you were chased out. So as soon as youreached the score they increased it.DAVID KHUBEKA: I started working for LiteMaster on23 September 1963. I worked in the Automatic Departmentoperating many machines. We had to work faster all the time.storyI was changed to one machine making lampholders. I wasworking so hard that my hands were burning and bleeding.During that time management were 'boxing' the workforce.If you said anything you were chased out — no goingto the office to discuss it.When a foreman wanted to move you, you were takenroughly — not asked nicely.A white mechanic was hitting a black worker — and theworker was chased out.The work was dirty but there were no overalls. Duringthat time you were not allowed to ask for an increase. Ifthere was an increase it was one or two cents — no more.They were chasing out workers all the time. There was nounion then. Before MAWU came there was a TUCSA union,but they started by seeing management and then came to us.This was not the right way.WORKING FOR LITEMASTERI started working for LiteMaster on 19 January 1975. Theytold me there is a score (production target) at LiteMaster. Iasked them what is a score? I told them I had come to doany job and I know all the jobs, so they employed me. MrLampke and Mr Mdamane employed me.I first worked in the Appliances Department makingtoasters, irons, fans and table-lamps. There were no overallsat the time. I worked there for eight months. I then movedto the Stamping Department. I was sent all over the factorydoing different jobs. I told them I only wanted to do onejob. I was left alone with five machines. I made parts fortoasters. There was a coloured man, Len Con, who set themachines. He was a clever guy because he kept his job.There was a time when they gave me an increase of threecents. I took the amount out of the envelope and gave itback to the foreman because I was not satisfied.After they realised I was a hard worker I was shifted toSTOP PRESSVICTORY FOR WORKERS!Nearly 2 years after thedismissal of 65 Litemasterworkers, they have nowwon their jobs back withback pay as from 10 November1984 by order of theIndustrial Court. Throughoutthis period they continuedto maintain disciplineand solidarity. ThirtyLitemaster workers were,however, not awarded theirjobs back. Ntuli promisesthat they will continue tofight to have these workersreinstated.Richard Ntuli points out the LiteMasterfactory.STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong> 13

meeting we — the LiteMaster workers — approachedmanagement to ask for an agreement, to see if they wouldwork with MAWU. The management was still working withthe liaison committee. We asked the question: 'Who electsthe shop stewards and the liaison committee?' We also havethe right to remove them. We asked the liaison committee:'What good have you done for workers?'They answered: 'We have persuaded management to buildgood toilets. We have asked them to build a canteen wherewe can have meals with the white workers. We have askedthem to make good gardens around the factory.' I answered:'We have toilets in the location or you can answer the call inthe veld. We are here to work, not to eat — we eat in thelocation. We are not here to relax in green gardens and lookat beautiful flowers. What have you done for workers?'A union member makes a point at a meeting.the Stores. We worked hard in that department — with barehands and wearing only dustcoats.There was a misunderstanding over bonuses. I refused R7because I was working hard. This was increased to R21. Itwas coming only to me — not to the others. They tried tokeep me quiet. At this time they were moving me arounddepartments to work on sorting. This was 1977. I wasconnected with some black consciousness guys and theyshowed me how to secure the position for blacks.JOINING OUR UNIONI had read about the Natal Metal union joining our union inthe newspaper Ilanga. There was a guy from Salcast inBenoni and he took me to the Bree Street offices of theFOSATU Project. (The FOSATU Project was set up torecruit members before extending industrial affiliates in theEast Rand). There I met an organiser, Aaron Mati, whoexplained how the employers rob the workers and abouttrade unions. Andreas and I joined. When we got back to thefactory we recruited five guys and took them to the officesin Johannesburg. They also joined. After that we spread it toall the workers. I was called in to see the foreman, MrLampke. He told me that if I was not satisfied with the jobI must go and find another. I replied that if he was not happyhe should look for another job as well.This was 1979. With so many guys joining we withdrewfrom the FOSATU Project to join MAWU. It was difficultto speak to workers about the union. But at this timemanagement tried to bring in its own union and this gave usa chance, a platform to explain what a union was.From 1979 secret meetings were held outside the factoryat lunchtime with Moses Mayekiso of MAWU. We wereformulating ways of organising the workers inside thefactory. On Saturdays we would visit the MAWU offices toask what is a union, what will it do for the workers. Asmembership grew we met on alternate Saturdays inJohannesburg and in the locations — at Kwesime Hostel andthen Intokoza Higher Primary School.By this time management knew what was going on andsome people were speaking evil to them about me.One day at Kwesime Hostel in Katlehong we wereconfronted by the police. They gave us fifteen minutes toget out. Our membership was very high there. At thefollowing meeting in Johannesburg we elected shop stewardsand met with shop stewards from Scaw Metals, NationalSprings and Henred Fruehauf. In 1980 the office wasopened at Morena near Katlehong and after that we startedto hold local shop steward council meetings.At this time Moses Mayekiso and I planned a meeting atthe Hall in the location and sent out pamphlets. The purposewas to organise all the workers of Germiston. After theTHEY TRIED TO CONFUSE THE WORKERSWhen management tried to get us to work with the liaisoncommittee we refused. There they tried to confuse workers.Gerald Mamabolo, the personnel officer, was sent to askworkers if they knew about MAWU and to tell them therewas already a union and it was the same thing. In the endthere was a vote of workers. Out of 300 workers only 19voted for the liaison committee. The rest voted for the shopstewards. From then on we met with management, This wasin 1981.At the first meeting with management we demanded aminimum of R2.00 per hour and an increase of twenty centsper hour across the board. The company told us they hadno money. We fought vigorously. We knew production wasgoing well. At the second meeting they said they would givefive cents — not more. We reported back to members to takethe mandate after each meeting. At the third meeting theyoffered eight cents and then it was deadlock. The next daythe Technical Manager, Paul Derer, asked to meet with onlytwo of the shop stewards — myself and Gibson Xala. It wasnot easy. We pressed hard. In the end we were offered tencents.When we reported back to the workers we were mandatedto tell management that we were not satisfied and to ask theTechnical Manager to come and address the workers. Whenhe came he was asked many questions, but he could notanswer and left us standing without solutions. The workerscalled him back to explain. He then ordered us back to work,but no one moved. The shop stewards tried to speak to himagain. Paul Derer said T can fire twenty workers now andhave twenty at the gate and pay them more than you get.' Healso said we were not using our brains in asking for aminimum of R2.00 per hour. Then he said we were alldismissed.When we reported back he followed us, We told him to goback to the office and arrange our payments immediately.Then the workers all agreed to go back to work. All thishappened before 3 o'clock tea time, so it did not take long.When Paul Derer returned he pretended to be surprised tosee us working, and said he had prepared our pay packets. Hetold us that there were some elements who should be fired.At 5.00 p.m. the paymaster and the managers were waitingat the gate with the pay trolley to pay everyone out. Theworkers refused to accept this and Samson Dlamini and Iopened the gates to let workers out. Next morning —Thursday — we started work as normal but there were noclock cards. Nothing happened that day, but the foremanrecorded that we were working.SILENCE BETWEEN MANAGERS AND WORKERSOn Friday the clock cards were returned. Now there was14 STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong>

silence between management and workers. Friday afternoonwe got paid, but we were suspicious when the pay trolleystarted at the last department instead of from the office asusual. Some people's packets were not in the trolley and theywere told to go to the office for their money. Mr Xala and Iaccompanied workers to see what was going on. The vicechairmanof the shop stewards had already accepted hispacket, which included his unemployment card. Twentytwowere dismissed.THE UNION STEPS INWe informed the union. The union rep came the next weekand Stood at the gate to see management block the 22 fromentering the premises. He went with them to collect their payand to check what papers they were given to sign. This wasOctober 1981.The union then went to the Industrial Council Court todemand reinstatement. The struggle was hot; some cowardswithdrew from the movement. The dismissed peoplecontinued to meet in the Morena office to hear what washappening in the factory, and with the Industrial Council.Inside the factory we put pressure on with a go-slow. We helda meeting with MAWU officials from Cape Town andPietermaritzburg and the surrounding areas to discuss theproblem and to encourage the workers in the struggle.When management tried to get us to work overtime tocover for the dismissed workers, most people refused butmanagement approached a few individuals who agreed. Thesepeople were confronted and beaten. They were forced tostay in the factory at night. They phoned the manager forhelp with transport, but he was no help to them — he justwent back to bed. Next day they all went home, but theywould be paid for the day. I asked Paul Derer if I could alsogo home to sleep and still get paid? He asked, 'Who beat theovertime workers?'Next day we all received the December bonus and thenthe company closed down for the holidays. During that timewe contacted lawyers to continue the case. When wereturned to work in January 1982 the management was stilltalking about overtime, but now no one tried to workovertime. Management was annoyed at the case and said if Iattended I would be fired. I attended the case and on the lastday the director took me back to the factory in his car.There was no discussion, only silence. As a result of the caseall the workers were re-instated with six weeks back pay forhalf the time they were out. When they returned on Mondaythe company refused to let them in, so Mayekiso and BernieFanaroff arrived to talk with management. They said thesepeople had been fighting and stealing food from the canteenand that they only had work for three workers. Mayekisoreported back to the 22 workers. They said they were notprepared to send only three back. They had all been firedat the same time for the same reason.We reported this to the Johannesburg office, who wentback to the lawyer. The company agreed to meet the unionwith Mayekiso and Fanaroff present. The management calledin the workers and each was sent to their previous jobs. Somewere not given back their jobs: Wanda Masemola — a driver —was employed as a gardener. Livingstone Nagoxo — aninspector — was made a clerk, and Gibson Xaba was movedfrom storekeeper to parts supplier. The 22 workers receivedtheir back pay and found that money had been deducted forthe pension fund for twelve weeks.MEETING AT MORENAAfter two or three days a general meeting was held at MorenaStore when we planned to go ahead with negotiations for arecognition agreement.Negotiations were tough. We met sometimes three timesa week with management for six months; each time there wasa deadlock. The Agreement was signed on 22 July. Most ofthe problems were over grievance procedure. By this time wewere also pushing for another increase, but managementwould not agree to two sets of negotiations at once.About this time management introduced the 'value arch',with two workers from each department meeting managementto plan the jobs.AN UGLY INCIDENTThere was also an ugly incident at this time. A group ofworkers who belonged to Steel, Engineering and AlliedWorkers Union went to management complaining ofintimidation by MAWU. The management called in the policeand these workers pointed out some of our members. Mostof the shop stewards were on a training course at theUniversity; only three were left in the factory. Two werearrested. The accused were called in to the office, told therewas something wrong with their pay packets, and then put inthe police van. The third, Enoch Khowane, suspected andrefused to go to the office — so the police came into thefactory to take him. Everyone stood up and followed thepolice. The police pulled him into the van and drove off. Theworkers refused to go back to work. Management phonedthe union to complain that workers were not working. Therest of the shop stewards returned; by this time the workershad gone. Management called the stewards into the officebut we refused to go.On Monday the Elsburg police went to the location andarrested more members, including Samuel Skhosane, PeterMdonsele and Selby Shabalala. The three arrested on Fridaywere released on R300 bail, after being charged under theIntimidation Act. Six people were arrested during the week,but the company had them released because of the pressureof the workers.WE ASKED FOR EXECUTIVE CARSFrom there we demanded that management give us transportto go and lay charges against the non-MAWU people — asmanagement had given them transport. We were offered atruck. We refused and asked for the executive cars. We weretaken up to the Elsburg police station in two Mercedes, twoGolfs, six Audis, and a Ford three litre. The stationcommander tried to get us to drop charges — but we wouldnot because he had accepted the earlier case. We returned inthe cars, with the station commander, to hold talks with thecompany to settle out of court.The company said they were not responsible for thearrests. We said they had provided the transport to the policestation. The commander said he was going to stop the case.We were given papers to sign to drop our case against theothers, but we refused. When the case came up — on 4 November1982 — it was dropped. All this disturbed negotiationswhich only resumed in January 1983. Then the directorresigned and we were told there could be no morenegotiations until his replacement arrived on 1 May.In 1981 we had received the Industrial Council increaseplus ten cents. In 1982 we just received the IndustrialCouncil increase. We kept pushing management and in March1983 got twenty cents plus a promise of ten cents to be paidin July (the starting rate was R1.58 at this time). We receivedthe extra ten cents in July for one week, then we were allfired. But before this they fired the man responsible for the'value arch'. Forty were retrenched, a technical manager, MrHome, was fired because he was on our side. On the twelfthSTAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong> 15

or thirteenth of July we were all dismissed and then one daylater selectively re-employed. A list of 88 were not takenback. The management said we were fighting, carrying barsand striking. But stoppages were caused by managementrefusing to negotiate with workers. The sacked workersformed a steering committee at Morena. We met managementwho said the 88 would be re-employed group by group. Bythe following day management started hiring colouredworkers. Those members left in the factory started to leaveto join us at Morena; it was obvious they would have to teachthe job to the coloureds — and then be fired themselves. Thecompany sent a security guard to Morena to see what washappening and to complain that workers were being beatenand told not to work. This was not true.WE TOOK THE CASE TO THE INDUSTRIAL COURTIt took a long time to get our case to the Industrial Courtdue to misunderstanding with the MAWU organisers. Thefirst lawyer we saw believed the company's side of this story.The general secretary at the time, Mr Sebabi, said we had aweak case and it would cost too much. In the end we usedour own pension contributions to pay a deposit for a lawyerto take the case. In the early days we went to the East RandAdministration Board. They said they would not register anynew workers for LiteMaster. At the Manpower Departmentthey sent us next door — but they would not help us. On2 May 1984 our case was heard before the Industrial Council,but there was deadlock and it was referred to the IndustrialCourt. We are still waiting for the case. Of the original 88dismissed and the 40 who supported them, 100 to 130 stillmeet three times a week. We meet to push the case and toteach the merits of unity. Someone from Wits came to teachabout union activity.WAITING FOR JUSTICEThere have been several reporters come here and a womanfrom Germany enquired about our case. LiteMaster's headquartersare in Germany. That was in August or September1983, and we haven't heard anything since then.It has been very difficult without work. We had to dependon neighbours and friends. We wrote letters for assistance butthere has been little outside support. Now many of themembers are behind with rent and have been served witheviction notices.In LiteMaster there are still some union members left butwe hear rumours that most have had to leave the union. Thestop orders come to only R17 or R19 a month and subs areR1.20 each.YOUNG MALE WORKER: I blame the government which isin favour of the white population. We are suffering becauseof the colour of our skin. No white suffers. The unions werecreated to solve this problem.FEMALE WORKER: I am still prepared to go forward. Iam not prepared to work for a company which has no unionin it.MALE MIGRANT WORKER: In the homelands you find aman is given a place which is full of trees and this is supposedto be the field he is to cultivate. First it has to be cleared andat the first harvest you may only get 100 bags. But next timeyou will try to get more. In other words I am still preparedto go forward with the struggle.All of us are prepared to go forward with the struggle.Phambili NgnoForwardAndries W. Oliphant Farouk StemmetT. he Invisible MenThe men who left Ulundi, Umtata, SalisburyAnd Lorenzo MarquesFor the city of goldWhat happened to them?They leftFirst on foot,Then on horseback.Later on wagons.Now they leave on railway busesAnd overcrowded third-class trains.Does gold make man invisible?Who built the skyscrapersAnd tend to the gardens of luxurious homes?Who inhabit hostels,Crawl out of shacksAnd sleep with women who worship men?Coming in from a windswept nightTo the warmth of a caveI am told:Gold makes man live, underground.In Maputo the men who left for the city of goldArrived triumphantly with Frelimo.In Harare they marchWith the Seventh Brigade.In Umtata, Ulundi and GoliI continue searching for the men who dig gold.Andries W. OliphantU ntitledanother just-too-short weekend draws to a closewhileanother much-too-long week looms aheadand like all faithful cogs in the unstoppable machineI will take my place.Whenever I canI quietly slip outof the unstoppable machineand lodge myself into the new one:the one not quite complete,the one only just starting to move,but the one which promises, once in motion,to not merely stop the unstoppable,but to put it out of existence —totally, completely, once and for all!I feel comfortable in this new machine —for it is not of iron and steel,but of flesh and blood . . .Farouk Stemmet16 STAFFRIDER, VOL. 6 NO. 2, <strong>1985</strong>