Limpopo Leader - University of Limpopo

Limpopo Leader - University of Limpopo

Limpopo Leader - University of Limpopo

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

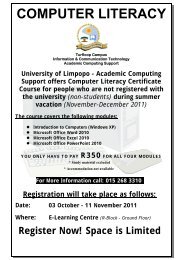

LIMPOPONUMBER 17AUTUMN 2009IeaderDISPATCHES FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF LIMPOPOWORLD ECONOMIC CRISIS:Tito Mboweni visits TurfloopFULL MEDICAL SCHOOL FOR LIMPOPO:It’s definite and imminentTRANSPORTATION IN SA:The <strong>University</strong> lends a hand

What have you been reading lately?SUBSCRIBE SUBSCRIBE SUBSCRIBEto <strong>Limpopo</strong> <strong>Leader</strong> and be informed by theprovince’s most dynamic magazineStudents subscribe now and save 50%Subscribing to <strong>Limpopo</strong> <strong>Leader</strong> Magazine for ONE YEAR costsjust R50 per annum for Students & R100 per annum for Alumniand local subscribers!• Student subscriptions MUST include your student number• Subscribe by post and include your pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> payment• Subscriptions can be paid directly to DGR Writing &Research’s account• Or by cheque made payable to DGR Writing & Research• Pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> payment FAXED with subscriber’s full details to: (+27) 011 782 0335Account Details:Bank:Standard BankBranch:MelvilleBranch Code: 00-61-05Account Number: 002 879 336Account Name: DGR Writing & Research ccReference:Subs/(+ your initials & surname)Contact: Clare-Rose JuliusTel: (+27) 011 782 0333 Fax: (+27) 011 782 0335 Cell: 072 545 2366Email: info@developmentconnection.co.zaPO Box 2756, Pinegowrie 2123, Gauteng, South Africa

LETTERS TO THE EDITORA REQUEST FROM UGANDAI AM A FREELANCE JOURNALIST BASED IN UGANDA, AND I WASREADING <strong>Limpopo</strong> <strong>Leader</strong> NUMBER 14 ONLINE. It had some veryinteresting pieces. I saw the article concerning the Dr George MukhariHospital, and I am especially interested in getting in touch with with one<strong>of</strong> the hospital’s public relations people, like Kealeboga Mohajane. Is thereany chance you could help me getting in touch with her, or any <strong>of</strong> hercolleagues? Thanks in advance.ARNE DOORNEBALUganda.We have sent the relevant contact details to this correspondent – Editor.HERE’S ANOTHER RESPONSE FROM THE EDITORSEVERAL TIMES RECENTLY, I HAVE BEEN QUESTIONED REGARDING THEUSE OF EPITHETS AND TITLES IN <strong>Limpopo</strong> <strong>Leader</strong>. We have followednational and international print media style in this regard. The full designation– pr<strong>of</strong>essor or doctor or governor or minister – and the first name is used atthe first mention; thereafter surnames only are used. Terms like Mr and Msare never used. The first name usually reveals the gender; otherwise theearly use <strong>of</strong> pronouns – he or she – will clarify the situation – Editor.pPREFERENCE WILL BE GIVEN TOSHORT LETTERS. Aim for a maximum<strong>of</strong> 100 to 150 words or expect yourepistle to be edited. Please givecontact details when writing to us.No pseudonyms or anonymousletters will be published.ADDRESS YOUR LETTERSTO:The Editor<strong>Limpopo</strong> <strong>Leader</strong>PO Box 2756Pinegowrie 2123South AfricaFax: (011) 782-0335E-mail: dgrwrite@iafrica.comBudget Accommodation (Cape Town)Riverview Lodge (Observatory)• FIVE-STAR budget accommodation• Ideal for large/small GROUPS• CONVENIENTLY situated close to UCT and all that CAPE TOWN <strong>of</strong>fers• HOLIDAY accommodation• RATES: From R125 per person sharing (BED & BUDGET BREAKFAST)Meals available upon requestPhone: (021) 447 9056Fax: (021) 447 5192Email: info@riverview.co.zaWebsite: www.riverview.co.zaP A G E 1

<strong>Limpopo</strong> <strong>Leader</strong> ispublished by the Marketing andCommunications Department,<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>,PO Box X1106,Sovenga 0727,<strong>Limpopo</strong>,South Africa.HYPERLINK “http://www.ul.ac.za”www.ul.ac.zaEDITOR: David Robbins.Tel: 011-792-9951 or082-787-8099 ordgrwrite@iafrica.comADVERTISING:Clare-Rose JuliusTel: 011-782-0333 or072-545-2366EDITORIAL COMMITTEE:DK Mohuba (chairman)Daphney KgwebaneNorman NyazemaElizabeth LubingaDavid RobbinsGail RobbinsARTICLES written by JANICEHUNT: Campus with a Past –Part Two, School <strong>of</strong> DentistryRises High Above Mediocrity,The School That’s Taken aBig Bite Out <strong>of</strong> Life, The Highsand Lows From the Top:Pages 24 – 32PHOTOGRAPHS:Robbie Sandrock – pages:cover photograph, top left &bottom right 16, 23;Liam Lynch – pages: top right16, 21, 24, 25, 28;The Bigger Picture – pages:back cover, 4, 5, 8; ULarchives – page: 11;David Robbins – pages: top &bottom 6, 9, 13, 15, bottomright 16, 18;Medunsa campus LibraryArchives – pages: 27, 30, 31esDESIGN AND LAYOUT:JAM STREET DESIGN (PRETORIA)PRINTING: Colorpress (pty) LtdPRODUCTION MANAGEMENT:Gail RobbinsDGR Writing & ResearchTel: 011-782-0333 or082-572-1682 ordgrwrite@iafrica.comARTICLES MAY BE REPRINTEDWITH ACKNOWLEDGEMENT.ISSN: 1812-5468EDITORIALaAN IMPORTANT FOCUS IN THIS 17TH EDITION OF <strong>Limpopo</strong> <strong>Leader</strong>MUST BE THE COMING OF LIMPOPO’S NEW TERTIARY HOSPITAL ANDTHE FULL MEDICAL SCHOOL THAT WILL BE ATTACHED TO IT. In somerespects this is old news. Ever since the merger between the old<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> the North and Medunsa (the medical university close toPretoria) at the beginning <strong>of</strong> 2005, an improved health sciences trainingplatform for the province has been on the cards. Only the when and thehow have been under constant discussion. What has finally emerged isthat the merger will mean a duplication <strong>of</strong> training facilities rather thantheir physical relocation. A task team has now been established toco-ordinate the wide-ranging activities that are necessary to get the newfacilities <strong>of</strong>f the ground, as well as the teaching that needs to take placefor the facilities to be fully and effectively utilised. Some key facts arebeginning to emerge: exactly where the new facilities are to be built;when the first intake <strong>of</strong> medical students will be admitted; and so on.Particularly interesting is what already exists in the Polokwane andMankweng hospitals that will form the basis <strong>of</strong> the medical school, andthe work now going on to strengthen the allied health departments <strong>of</strong> theschool, which will include training for such pr<strong>of</strong>essions as dentistry,physiotherapy, pharmacy, radiography and the like. Our coverage onthe latest developments (that are <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>ound importance to Polokwane,the province, and indeed the SADC region) starts on page 17.Closely allied to this news is the appointment <strong>of</strong> a new ExecutiveDean <strong>of</strong> Health Sciences to oversee activities both at Ga-Rankuwa (theold Medunsa campus) and at the university’s headquarters at Turfloopand Polokwane. It’s going to be a difficult job. However, if pastexperience is anything to go by, the appointee, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Errol Holland,will be equal to it. Hard to imagine these days that Holland, afterqualifying as a specialist haematologist during the 1970s, was debarredfrom working at the Johannesburg General Hospital because <strong>of</strong> thecolour <strong>of</strong> his skin.There’s plenty more to occupy readers with our coverage <strong>of</strong> SouthAfrica’s transportation challenges and the university’s contribution totheir resolution; and with the annual visit to Turfloop <strong>of</strong> Tito Mboweni,Governor <strong>of</strong> the Reserve Bank. He spoke candidly to economics studentsabout the world economic crisis and had some penetrating things to sayabout Africa’s propensity to development aid dependency and tocorruption.Finally, there’s part two <strong>of</strong> our anecdotal history <strong>of</strong> the Ga-Rankuwacampus, this time shedding particular light on the early days <strong>of</strong> theSchool <strong>of</strong> Dentistry there. Enjoy.NEXT ISSUEA TURFLOOP ACADEMIC IS TEACHING FRENCH TO CHILDREN IN THESOVENGA COMMUNITIES SURROUNDING THE UNIVERSITY. Eccentricor realistic? When the sheer size <strong>of</strong> Francophone Africa is taken intoaccount, the answer may well be the latter. It’s another sign that SouthAfricans, after the isolation <strong>of</strong> apartheid, are moving closer to being part<strong>of</strong> the continental main. We’ll also be examining the relationship betweenthe <strong>University</strong>’s School <strong>of</strong> Education and the provincial education authorites.Water will be another important focus. Aves-vous soif de plus?P A G E 2

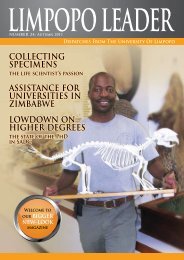

IN THIS ISSUEcover picture:A young doctor at work in Mankweng Hospital – one <strong>of</strong> theinstitutions that will be involved in the full medical training platformcoming to Polokwane.page 4:Getting from A to B in SA. THE TRANSPORTATION CHALLENGE, anAmerican expert speaks; and an update on <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>involvement.page 8:Getting from A to B in SA. WHAT’S IN THE PIPELINE?page 10:WORLD ECONOMIC CRISIS – the university’s involvement.page 11:TITO MBOWENI AT TURFLOOP – The Governor <strong>of</strong> the South AfricanReserve Bank gives his annual lecture.page 14:THE SOCIAL IMPACT <strong>of</strong> the economic crisis in South Africa.page 17:COMING AT LAST, <strong>Limpopo</strong>’s very own medical training platform.page 19:<strong>Limpopo</strong>’s medical training platform – WHAT’S ON THE GROUNDALREADY?page 20:THE OTHER HALF <strong>of</strong> a medical school comprises the allied healthpr<strong>of</strong>essions.page 21:A COMPLEX AND CHALLENGING TASK. Pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essor ErrolHolland, new Executive Dean <strong>of</strong> the Faculty <strong>of</strong> Health Sciences.page 24:CAMPUS WITH A PAST. Part 2 <strong>of</strong> our extensive look at theanecdotal history <strong>of</strong> the medical activities on the Ga-Rankuwa campus.page 25:Campus with a past – SCHOOL OF DENTISTRY RISES HIGH ABOVEMEDIOCRITY.page 28:Campus with a past – THE SCHOOL THAT’S TAKEN A BIG BITE OUTOF LIFE.page 30:Campus with a past – THE HIGHS AND LOWS FROM THE TOP.

Getting from A to B in SATHE TRANSPORTATION CHALLENGEwWE ALL KNOW THE MAINELEMENTS OF THE SOUTHAFRICAN TRANSPORTATIONSTORY: INADEQUATE PUBLICTRANSPORT, SPORADIC TAXIWARS, CONGESTED ROADS,HIGH ACCIDENT RATES, ANDAN UNDER-UTILISED RAILWAYSYSTEM. It’s very <strong>of</strong>ten quite anightmare trying to get around.Little wonder, therefore, thatconsiderable interest was shownin a lecture on the subject deliveredin March on the Turfloop campus<strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>.‘Transport Management inSouth Africa: Challenges andProspects’ was presented byDr Oliver Page <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong><strong>of</strong> Michigan TransportationResearch Institute in the UnitedStates. Page was well-qualified todeal with such a subject, havingworked earlier this decade as atransportation researcher withSouth Africa’s CSIR for five years.A delegation from the CSIRtravelled from Pretoria to attendPage’s presentation, as didrepresentatives from the transportdepartment <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Limpopo</strong>provincial government. Thepresence <strong>of</strong> these bodies on theTurfloop campus was significantbecause the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Limpopo</strong>, in collaboration with theCSIR, had designed a Bachelor <strong>of</strong>Administration in TransportManagement degree that kicked<strong>of</strong>f in 2005 with nearly 50 students.Most <strong>of</strong> them had been awardedfull bursaries from <strong>Limpopo</strong>province in exchange for a threeyearemployment commitment tothe Department <strong>of</strong> Transport.A further 50 have been enrolledeach year since then in a dealthat is worth R17-million overseven years. (See story in box onpage 7: Is <strong>Limpopo</strong> provincegetting its money’s worth?)P A G E 4

The Bigger PictureThe original motivation behindthis development was straightforward:to improve the levels <strong>of</strong>specialised transportationexpertise in the province and toenhance the status <strong>of</strong> transportationmanagement generally.During his presentationPage identified anotherimportant function. He spokeabout the urgent need for moreresearch capacity in the countryto cope with mounting pressurefrom the numerous challengesconfronting transportation inSouth Africa. ‘I know that studentsare keen to turn their academicachievements into real economicimprovements as soon as possible.But a real national need is forcapable people to work inresearch. There simply aren’tenough transportationresearchers. Students shouldseriously consider this option: theywill get to travel, and to becomeinvolved in cutting-edge projects.It’s a really worthwhile career.’The content <strong>of</strong> Page’s presentationcertainly underscored theseclaims – while at the same timepainting a frequently sombrepicture <strong>of</strong> a country facing acollection <strong>of</strong> transportationproblems in urgent need <strong>of</strong> seriousexamination and resolution.Page isolated several criticaltransportation issues confrontingSouth Africa, and indeed theworld, with the problem <strong>of</strong> trafficcongestion being the mostimportant. ‘Congestion,’ Pagesaid, ‘is a symptom <strong>of</strong> excessdemand over supply <strong>of</strong> roadspace. There are two types –intermittent congestion caused byspecial events or accidents; andrecurring congestion, for exampleduring morning and afternoon‘rush hours’ – that have becomeendemic to any given road system.’P A G E 5

Getting from A to B in SATHE TRANSPORTATION CHALLENGEPr<strong>of</strong> Obeng Mireku and Dr Oliver PageFROM LEFT Pr<strong>of</strong> Obeng Mireku, Polly Boshielo and Dr Oliver Page with Turfloop campus colleaguesGauteng, for example,experiences the latter type, whererush hours have steadily extendeduntil at no time <strong>of</strong> the workingday does congestion cease.The costs <strong>of</strong> congestion arevaried and can quickly becomeserious. They include economicconsequences: people can hardlybe economically active when theyare stuck in the traffic.Environmental consequences:pollution from slow-moving trafficis becoming a severe problem.Health consequences are mademanifest through increases inrespiratory diseases andincreased incidents <strong>of</strong> road rage.Finally, logistical consequencesoccur when deliveries <strong>of</strong> goodsand services are delayed.Expanding outwards from thisfundamental critical issue, Pageidentified the major challengesfacing South African transportationsystems.Beginning with the country’sroads, he pointed out that thegrowing congestion and highaccident rates could be attributedto various factors, not least <strong>of</strong>which was ‘the migration <strong>of</strong> carg<strong>of</strong>rom rail to road to a point whereonly 12 percent <strong>of</strong> freight iscarried by rail while the remaining88 percent is hauled across theroad network’. The Durban toGauteng corridor was particularlyoverloaded. Another contributingfactor to the lack <strong>of</strong> road supplywas that road-users did not payfor the true costs <strong>of</strong> road use,resulting in surface deterioration<strong>of</strong> road infrastructure and limitednew construction. There was alsoa disparity between urban andP A G E 6

IS LIMPOPO PROVINCEGETTING ITS MONEY’SWORTH?rural road supply, with theadvantage weighted heavily infavour <strong>of</strong> the former.‘The country’s railways als<strong>of</strong>ace severe challenges,’ Pagecontinued. ‘They stem largely fromlack <strong>of</strong> investment in the system.The result is ageing rolling stockand infrastructure, which in turnmeans that freight throughput andcapacity are limited. This iscoupled with low staff skill levelswhich translates into generallypoor and unreliable servicedelivery. All this is exacerbatedby widespread theft <strong>of</strong> cabling inparticular, and by wilful damageto infrastructure.’The result <strong>of</strong> these challengesis a public transport network withserious challenges <strong>of</strong> its own: anageing minibus fleet; minibus taxiviolence; supplier-driven farestructures; and a general publictransport environment <strong>of</strong>criminality and insecurity.What can South Africansexpect? Page listed a number <strong>of</strong>developments that will benecessary to improve SouthAfrica’s ailing transportationsystems. Among the mostimportant were:• Major upgrading andrefurbishment <strong>of</strong> the railwaysinfrastructure.• More customer-driven railservices like the SowetoBusiness Express and theGautrain.• The decentralisation <strong>of</strong> railservices.• The taxi recapitalisationprogramme to continue.• Improved automobile safetyfeatures – anti-locking brakesand electronic stability control– to become mandatory on allvehicles to reduce accidents.• Improved safety and securityon and around public transport.• The introduction <strong>of</strong> integratedrapid transit systems thatwould combine minibus taxiservices with formal bus andrail routes on one ticket.• Transponders fitted to vehiclesto complement the currentmanual systems on toll roadsand speed up the flow <strong>of</strong> traffic.However, Page is acutely awarethat the success <strong>of</strong> all theseprospects or suggested improvementswould be heavilydependent on the acceleratedtraining <strong>of</strong> transportation personnel,from drivers and maintenancestaff to managers, planners and(yes, you’ve guessed it)researchers.‘What is needed,’ he told hisTurfloop audience, ‘are increasedbursary and sponsorship opportunities,increased partnerships withinternational universities andresearch and developmentinstitutes, more versatilemanagement developmentprogrammes capable <strong>of</strong> deliveryas full- or part-time courses; andserious consideration needs to begiven on how to reward personnelwith scarce and critical skillswithin the transportation sector foroutstanding performance.’THE QUESTION CONCERNSTHE PARTNERSHIP BETWEEN THEUNIVERSITY OF LIMPOPO ANDTHE CSIR, THE TWOORGANISATIONS WHICHDESIGNED THE DEGREE INTRANSPORTATION THAT HASBEEN TAUGHT ON THETURFLOOP CAMPUS SINCE2005.‘Most emphatically, yes,’ saysPolly Boshielo, the provincialdepartment’s general manager <strong>of</strong>public transport and closely involvedwith the university-based programme.‘We’re getting our money’s worth.The programme is really helping toimprove our standards <strong>of</strong> transportplanning and management; andnew skills are being developed.We’re very keen to continue withthe partnership.’So far, 100 graduates havepassed the course, most <strong>of</strong> whomare employed in the TransportDepartment. A further 150 studentsare in training.Now, plans are afoot to changethe Bachelor <strong>of</strong> Public Administrationdegree to a BCom specialising intransportation economics, not leastpublic transport. ‘We’re pressingfor this,’ says Boshielo, ‘becausethat’s where the future <strong>of</strong> SouthAfrica’s transportation systems lies.Private transport will increasinglybecome too expensive and toocostly in terms <strong>of</strong> the environment.’Boshielo points to the NationalTransport Master Plan 2050 and tothe Public Transport Strategy Plan2020 for verification. ‘It’s importantthat as a province <strong>Limpopo</strong> acquiresthe necessary skills effectively toassist to put these important plansinto practice.’P A G E 7

Getting from A to B in SAWHAT’S IN THE PIPELINE?Imagine a frequent rail service speeding on widegaugetrack between Polokwane and Marble Hall.The route runs through some <strong>of</strong> the most denselypopulated parts <strong>of</strong> south-central <strong>Limpopo</strong>. A pictureemerges <strong>of</strong> a transportation system that willradically improve the developmental options forwell over a million people.The Bigger PicturetTHERE ARE BIG TRANSPORTATION PLANS FOR 21STCENTURY SOUTH AFRICA. First <strong>of</strong>f, there’s NATMAP2050. This is the national transport master plan thatbegan in 2005 and is scheduled to run to the middle<strong>of</strong> the 21st century. Then there’s the Public TransportStrategy and Action Plan 2007 – 2020, the result <strong>of</strong>extensive consultation with all stakeholders culminatingin the Transport Indaba held in Soweto in October2006 and approved by cabinet several months later.But what do these plans contain, and what are theimplications for <strong>Limpopo</strong> province? Polly Boshielo, theprovince’s general manager <strong>of</strong> public transport and agraduate <strong>of</strong> the Turfloop Postgraduate School <strong>of</strong><strong>Leader</strong>ship’s MBA programme, provides some <strong>of</strong> theanswers.NATMAP 2050, she says, is concerned with examining,determining and crystallising the relationshipsbetween various areas (whether industrial, urban,agricultural, etc) in the country and the transportationrequirements emanating from area-specific needs.‘The interaction between land use in the variousareas and the evolution <strong>of</strong> an integrated transportationplan is a fundamental planning consideration,’Boshielo points out. ‘The way in which transportationmaster plan unfolds must facilitate sustainablesocio-economic growth and should help to promotecoherent and integrated development planning acrossthe country.’NATMAP 2050 will focus on major nationaltransportation networks and macro planning. To dothis effectively a central land-use and transportationdatabank will be maintained. A few <strong>of</strong> the principlesthat will guide the planning process are:• To <strong>of</strong>fer a central transportation vision into whichprovinces can fit their own transportation plans.P A G E 8

Polly Boshielo, a senior transportation manager in <strong>Limpopo</strong>with an MBA from the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>’s TurfloopPostgraduate School <strong>of</strong> <strong>Leader</strong>ship• To make maximum use <strong>of</strong> existing transportationinfrastructure (roads and railways and airports)before developing new ones.• To gradually overhaul the country’s extensive railnetwork by shifting from the presently used 1067 mmCape railway gauge to 1435 mm gauge and theincremental introduction <strong>of</strong> high-speedrailway equipment and rolling stock.Slotting into the overarching master planning processis the shorter term Public Transport Strategy andAction Plan 2007 – 2020. The first phase <strong>of</strong> this planhas been designed to implement integrated rapidpublic transport networks (IRPTNs) in the 2010 WorldCup host cities, and hopefully in a few more places aswell. The second decade in the life <strong>of</strong> the plan willextend the IRPTNs to other cities and areas, which willultimately impact on half the total population <strong>of</strong> SouthAfrica.WHAT’S AN IRPTN?Boshielo points to the national documentation. It’s acentrally controlled transport network that incorporatesall modes <strong>of</strong> transport active in the network <strong>of</strong>transport corridors. ‘Imagine a network,’ saysBoshielo, ‘where trains, buses and taxis all form part<strong>of</strong> a single co-ordinated whole, getting people fromA to B in the shortest possible time, and supported byappropriate pedestrian and cycling networks withfacilities like footpaths and bridges, and park-and-rideamenities for motorists linking into the rail and roadservices <strong>of</strong> any particular IRPTN.’Such transportation services would require whatBoshielo called ‘intermodal facilities’ where thevarious modes <strong>of</strong> transport – trains, buses, taxis, aswell as private modes <strong>of</strong> transport – could interact,thus speeding up the travel time for ordinary people.She said that seven areas in <strong>Limpopo</strong> had alreadybeen targeted for the development <strong>of</strong> intermodalfacilities at the heart <strong>of</strong> IRPTNs. They were Polokwane,Giyani, Jane Furse, Mikado, Thohoyandou, Northamand Burgersfort.According to the national documentation, IRPTNswill aim for high frequency services (say every fiveminutes in peak periods) and between 16-and 24-houroperations. Wheelchair passengers will be cateredfor; and the network will prioritise walking and cyclingand the use <strong>of</strong> public transport over private car travel.As an example <strong>of</strong> the transportation improvementsin the pipeline for <strong>Limpopo</strong>, Boshielo refers to the‘Moloto rail corridor initiative’ that is planned tooperate between Polokwane and Marble Hall 120 kmto the south. The route runs through some <strong>of</strong> the mostdensely populated parts <strong>of</strong> the old so-called homeland<strong>of</strong> Lebowa. Now add the advantage <strong>of</strong> 1435 mmgauge tracks for extra speed to a high-frequencyservice (as outlined above), and a picture emerges <strong>of</strong>a transportation system that will radically improve thedevelopmental options for well over a millionpreviously under-served people. And there’s a roaddecongestion bonus into the bargain: currently morethan 500 buses work that particular route – vehicleswhich could be redeployed to provide feeder servicesthat penetrate deeper into the remoter rural areas.‘A specialist rail research company has alreadybeen appointed to undertake a preliminary study onthe Moloto corridor project,’ Boshielo says. ‘And thisis just one <strong>of</strong> the projects that will help to transformtransportation – and facilitate development – in ourprovince.’P A G E 9

21 20021 200WORLD ECONOMIC CRISIS21 20021 20020 40020 20020 00019 800tTHERE’S A WORLD ECONOMIC CRISIS GOING ON. Everybody knows that. Our television screens and newspapersare full <strong>of</strong> it. We’ve all heard about such things as sub-prime lending, credit crunches, collapsing banks,economic recessions, tens <strong>of</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong> job losses, increasing numbers <strong>of</strong> home repossessions. There havebeen sombre recollections <strong>of</strong> the Wall Street crash <strong>of</strong> 1929 when not a few investors jumped from skyscrapersrather than face disastrous stock exchange losses. If we’re students <strong>of</strong> economics we may even have enteredinto the current philosophical arguments symbolised by Adam Smith, the 18th century father <strong>of</strong> laissez faire,on one side, and on the other Maynard Keynes, the arch proponent, after the Great Depression <strong>of</strong> the 1930s,<strong>of</strong> state intervention into and control <strong>of</strong> national economies. But what does it all mean – and not least forordinary South Africans? In the pages that follow, some answers emerge from the Turfloop campus <strong>of</strong> the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>.19 60019 40019 20019 000To begin with, the Governor <strong>of</strong> the Reserve Bank, Tito Mboweni, is an honorary pr<strong>of</strong>essor in the Department<strong>of</strong> Economics and at the end <strong>of</strong> March he was on campus to deliver his annual lecture. He had some wisethings to say to a packed lecture hall. As counterpoint, the caretaker director <strong>of</strong> the School <strong>of</strong> Social Sciences,Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Sello Sithole, examines the socio-political consequences <strong>of</strong> the economic recession in South Africa.Both these contributions make for essential reading for those interested in the economic mysteries andanomalies that stalk abroad in the world today.18 80018 600P A G E 1 0

World economic crisisMBOWENI SPEAKS ON TURFLOOPCAMPUSGovernor Tito MbolweniINTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS;iSALIENT FEATURES OF THE SOUTH AFRICANECONOMY AND FINANCIAL MARKETS; KEYECONOMIC INDICATORS; MONETARY POLICY ANDINFLATION; AND SOME GOOD PRACTICAL ADVICE –THESE WERE THE MOST IMPORTANT SUBHEADINGSIN GOVERNOR TITO MBOWENI’S LECTURE.According to Mboweni, the real GDP (grossdomestic product) in the United States dropped by6,3 percent in the fourth quarter <strong>of</strong> 2008, a declinethat reflected contractions in exports, gross privatedomestic fixed investment and personal consumptionexpenditure. American unemployment increased to8,1 percent in February 2009 and the four-weekmoving average surged to 650 000 job losses in theweek ending 21 March 2009. Across the Pacific, thereal GDP in Japan contracted by 12,1 percent in thefinal quarter <strong>of</strong> 2008, due mainly to negativecontributions from net exports and private investment.Economic activity in Western Europe contracted by 5,7percent in the fourth quarter <strong>of</strong> 2008, mainly as a result<strong>of</strong> the decline in net exports, gross fixed capital formationand consumption expenditure; and the economicsentiment indicator declined further to 65,4 points inFebruary 2009. Mboweni mentioned these and otherfigures to show that the world economy was in badshape. According to the latest International MonetaryFund (IMF) forecasts published in March 2009, globaloutput was expected to contract for the first time inmany decades by around 0,5 to 1.0 percent in 2009.Thereafter, recovery would begin gradually, with globaloutput rising by around 1,5 to 2,5 percent in 2010.Oil prices had decreased sharply since mid-2008due to the financial crisis and slower global economicgrowth. The daily price <strong>of</strong> Brent crude oil, however,had gradually increased during March 2009. BrentP A G E 1 1

World economic crisisMBOWENI SPEAKS ON TURFLOOP CAMPUScrude oil futures prices are currently around US$54per barrel for delivery in the second quarter <strong>of</strong> 2009.South Africa’s export commodity price indexcontinued to recover through February 2009, althoughit remains much lower than the record highs registeredin early 2008. Inflation projections for advancedeconomies as well as emerging-market and developingeconomies were revised downwards for 2009 in theforecasts released by the IMF in January 2009,moving up again only in 2010.Meanwhile, South African banks had recordedstrong asset growth in recent years. Total bank assetsamounted to R3,2-trillion in January 2009, rising fromR2,7-trillion in January 2008, reflecting a growth rate<strong>of</strong> 20 percent over twelve months. This rate had nowslowed. Government revenue, boosted in recent yearsby improved tax compliance and administration, willalso decrease as economic activity slows, unemploymentrises and disposable income drops.Against this general background 1 <strong>of</strong> short-termgloom with brighter prospects for 2010, Mboweniprovided a set <strong>of</strong> specific interpretations to guide hisaudience to a more practical grasp <strong>of</strong> the crisis.He started by stressing that the global economywas inextricably integrated. What happened in onepart <strong>of</strong> the world affected other parts. He gave asan example the case <strong>of</strong> South Korea. That heavilyindustrialised country depended for its economicstability on the export <strong>of</strong> manufactured goods. If theUnited States, one <strong>of</strong> South Korea’s major exportmarkets, goes into recession, then demand for SouthKorea’s products lessens. Now add to this lesson incause and effect the fact that South Korea buys a lot<strong>of</strong> its raw materials from South Africa. Inevitably,South Korea’s raw-material demand is reduced, whichin turn means that South Africa will need to reduceraw-material production, which ultimately willtranslate into job losses in South Africa.‘We’re living in a connected world,’ Mbowenisaid. ‘There is no exclusively South African way <strong>of</strong>dealing with the crisis. We’re part <strong>of</strong> hugeinterdependencies. That’s what it means to be part<strong>of</strong> the global economy.’In consequence <strong>of</strong> these interdependencies,developing countries will not be able to escape theeffects <strong>of</strong> the crisis. African countries will definitely notescape, Mboweni said. However, they could alleviatesome <strong>of</strong> their vulnerability by reducing their relianceon development aid and by fighting the corruption intheir governments. He referred, as an example, toNigeria as ‘a potentially rich economy’, but thenalluded to the recent theft in a Nigerian port <strong>of</strong> anentire oil tanker.‘There’s a lot to be done in Africa,’ he told hisaudience. ‘Budgets and currencies in circulationshould relate to production levels. Corruption acrossthe continent will have to be stamped out, and selfsufficiencyaimed at. The continent must stopdepending on handouts from the developed world.’Mboweni said that the bulk <strong>of</strong> South Africa’snational budget was increasingly becomingindependent <strong>of</strong> remittances by forgeign donors.Budget deficits were not funded by the InternationalMonetary Fund, but by borrowing through openmarket transactions. The point, however, was not toallow large budgetary deficits. That meant livingwithin one’s means. Over recent years, South Africahad moved from large deficits to small deficits, and toa target <strong>of</strong> breaking even, or even to a small surplusas had occurred in the last financial year (2007/08).‘To run a big deficit now would not be sensible,’ hesaid. ‘It’s not a good time to go to the Sovereign BondMarkets: the recession has pushed up interest rates.’A member <strong>of</strong> the audience asked whether it wasa good idea to bale out industries such as the automobilemanufacturers. Mboweni replied by saying that‘no amount <strong>of</strong> state money will reverse shrinking orderbooks’. The industries themselves – management andlabour – should make their own arrangements to copewith reduced production. Shortened hours <strong>of</strong> work, jobsharing, and other solutions needed to be developedbefore actual job losses were incurred.‘Instead <strong>of</strong> trying to support ailing industries weneed to improve consumer confidence,’ Mboweniasserted. ‘This will take a while, and in the interim joblosses will be inevitable. Fortunately, in South Africa,the current high levels <strong>of</strong> public works – for example,the construction <strong>of</strong> the Gautrain and other 2010 infrastructure– will help with employment for a time. Butthe world economic crisis will be accompanied by1 Dorcas Manzini <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong> Communications Department collated the background facts used in this coverage <strong>of</strong> GovernorMboweni’s lecture.P A G E 1 2

negative social consequences in South Africa.’In this regard, Mboweni said it had surprised himthat the audience had asked no questions concerningthe impact <strong>of</strong> the economic crisis on South Africa’ssystem <strong>of</strong> social grants. ‘Perhaps we can discuss thatnext time,’ he concluded.A LINK INTO THE ECONOMICMAINSTREAMTITO MBOWENI, A FORMER MINISTER OFLABOUR, HAS BEEN GOVERNOR OF THE SOUTHAFRICAN RESERVE BANK SINCE 1999. He’s alsocarried on a special relationship with theDepartment <strong>of</strong> Economics at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Limpopo</strong> for most <strong>of</strong> that time. This relationship,which is the result <strong>of</strong> his affection for the university,is marked by the delivery <strong>of</strong> an annual lecture onthe Turfloop campus. The relationship was furtherstrengthened some years back when he was madean honorary pr<strong>of</strong>essor in the Department <strong>of</strong>Economics.Mboweni’s lecture at the end <strong>of</strong> March this yearis the sixth time in as many years that he hasspoken at the university. Primarily his audience iscomprised <strong>of</strong> economics students – although <strong>of</strong>course many in the university community areanxious to find a seat in the auditorium.‘We’re very grateful for this link into theeconomic mainstream,’ says Economics HODPr<strong>of</strong>essor Richard Ilorah. ‘It’s precisely the kind <strong>of</strong>linkage that we want for the department. In fact,it’s a great honour for students and staff alike.’The Department <strong>of</strong> Economics is a sizeableaffair. It’s part <strong>of</strong> the School <strong>of</strong> Economics andManagement, which in turn is housed in theFaculty <strong>of</strong> Management and Law. There are seveneconomics lecturers teaching 623 first years,172 second years and 88 third years. ‘Regularly,we duplicate lectures to cope with these highundergraduate numbers,’ says Ilorah.Of concern to Ilorah is the low number <strong>of</strong>postgraduate students: only 24 engaged inHonours degrees, seven working towards theirMasters, and three studying at the doctoral level.‘The reason for this is undoubtedly economic,’Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Richard Ilorahhe says. ‘Most <strong>of</strong> our students are from poor ruralbackgrounds. They get to university with the primepurpose <strong>of</strong> wanting to uplift themselves and theirfamilies from poverty. This is entirely understandable.A Bachelors degree is a passport to the world<strong>of</strong> work with access to financial resources. For now,that’s enough for most <strong>of</strong> them. But the result in thedepartment is this scarcity <strong>of</strong> postgraduate studentsand research. We’d love to turn this situationaround – and we will. But it will take time.’That is why Mboweni’s regular visits are soimportant. They have the potential to inspirehundreds <strong>of</strong> young <strong>Limpopo</strong> students to keeplearning, or to return to learning at some laterstage, and to inspire some <strong>of</strong> them to make a realcontribution to African and South African economicresearch and philosophy.P A G E 1 3

World Economic CrisisTHE SOCIAL IMPACTB Y S E L L O S I T H O L E 2tTHE CURRENT ECONOMICCLIMATE HAS STRIKINGPARALLELS WITH THEECONOMIC DEPRESSION OFTHE 1930S, WHICH WAS ALSOFELT FIRST IN THE UNITEDSTATES AND THEN SPREADTHROUGHOUT THE WORLD.Look at some facts about thecurrent economic climate in SouthAfrica:• ‘40 000 mine workers will losetheir jobs’ (mutiply this figureby 10 because each workerfeeds almost ten people)(Hill 2008:43)• Donor funding for NGOs thatprovide welfare services aredrying up• People are losing their housesand cars• Many small businesses aregoing belly up• The burden on the country’swelfare system will be heavy.(The xenophobic attacks <strong>of</strong> lastyear are just one indicator <strong>of</strong>a shrinking welfare pie.)It is true that every cloud has asilver lining – even if the lattermay not be visible to the nakedeye. The economic depression <strong>of</strong>the 1930s in the United Stateshad apocalyptic ramifications forbusiness and welfare. The impacton business was negative; on thewelfare front, however, thingswere much worse. However, anumber <strong>of</strong> positive and significantmilestones were also recorded.The combined failures <strong>of</strong> theeconomic system, privatecharitable agencies and state andlocal governments, placed socialwelfare much more firmly on thefederal agenda. In addition, the1930 Great Depression in theUnited States paved the way forthe election <strong>of</strong> Franklin Rooseveltto the presidency. Roosevelt, likePresident Barack Obama, had agenuine concern for others.Roosevelt had a personalexperience <strong>of</strong> polio, andObama’s parents, and Obamahimself to some extent,experienced ‘jim crow’. 3 Afterascending to power, Rooseveltintroduced policies referred to asthe New Deal, which weredesigned to reverse the economicwoes <strong>of</strong> the nation.The 1930 Depression in SouthAfrica had similar results. Theresponse <strong>of</strong> the then governmentwas to institute the CarnegieCommission to look into the PoorWhite Problem. Members <strong>of</strong> thecommission travelled throughoutthe country investigating theimpact <strong>of</strong> the ravages <strong>of</strong> thedepression on poor whitefamilies. After collecting data,the commission made thefollowing recommendations:• The establishment <strong>of</strong> a statebureau which would beresponsible for people’s socialwelfare (for whites only).• The training <strong>of</strong> skilled,university-educated socialworkers well versed in thesocial sciences.Consequently, the first statewelfare department was institutedin 1937, a development thatmarked the beginning <strong>of</strong>organised state intervention insocial welfare, the rapiddevelopment <strong>of</strong> courses for socialwork training in South Africanuniversities, and the pr<strong>of</strong>essionalisation<strong>of</strong> social work.It is inevitable that the currenteconomic recession will meanhardship in South Africa:unemployment will rise, andfamilies will face shortages <strong>of</strong>food, loss <strong>of</strong> shelter, and transportdifficulties. Families and marriagesbreak down during periods<strong>of</strong> scarcity. People who wereliving above the poverty linesuddenly have to strip themselves<strong>of</strong> their dignity, swallow theirpride, and queue for days on endfor unemployment insurancebenefit funds. Worse still, manywill be reduced to begging for2 Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Sithole is caretaker director <strong>of</strong> the School <strong>of</strong> Social Sciences on the Turfloop campus <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>.3 A euphemism for American-style racial segregation.P A G E 1 4

food and shelter from friends andrelatives. All this means that thosewho depend on the country’ssocial welfare system will increasein number and the system itselfwill be placed under huge strain.The current recession will alsoplace on the agenda a robustdebate about which welfaremodel to follow; and which onewould most effectively ensure oursurvival. Is it the minimalistselective model based on themeans test or the institutionalisedone that is universally accessible?The central question that weface in our country is: where dowe go from here? South Africahas developed a neo-liberaleconomy that is residualist in itswelfare provisioning. This meansthat the current crisis will stretchthe government’s spending tolevels that were never beforeimagined. This in turn will placepressure on the state to move,albeit incrementally, fromneo-liberalism to real socialdemocracy as the size <strong>of</strong> our‘welfare state’ expands.Another parallel with theUnited States is that the recessionappears to be at its worst just asSouth Africans went to the polls.In the United States, BarackObama was voted into the WhiteHouse with a clear mandate fromthe electorate to turn thingsaround. Too many Americanswere choking under increasedPr<strong>of</strong>essor Sello Sithole was born in Bela Bela and matriculated in nearby Mokopane. He went to the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong>the North (now <strong>Limpopo</strong>) where he graduated with a Bachelor <strong>of</strong> Social Work in 1983. After working for theTransvaal Administration for five years as a social worker, Sithole returned to his alma mater as a junior lecturerand continued his studies. He achieved his Honours degree in 1992, his Masters in 1998, and his doctoratethrough the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Pretoria in 2002. He’s been acting as caretaker director <strong>of</strong> Turfloop’s School <strong>of</strong> SocialSciences since 2007. Asked why he had chosen social work, he replied candidly: ‘My higher education was sponsoredby my minister, but with this proviso, that I either enter the ministry or serve society in some way.’ Sitholesmiled engagingly. ‘I was very young at the time. I didn’t think I’d make the ministry. So here I am.’credit card debts and mortgagebond foreclosures. Obama, withhis Yes WE CAN clarion call, haspromised relief in a number <strong>of</strong>ways, including increased socialspending.Interestingly, Obama’s clarioncall is echoed by the ANC’selection slogan: Working togetherWE CAN achieve more. Almostcertainly, South Africa’s 2009general election will usher in anadministration characterised bya leftist agenda and rhetoric.Will the forces <strong>of</strong> globalisationundermine the good intentions?Believers in increased governmentspending on the welfare frontmust hope that the new administrationwill have the courage <strong>of</strong> itsconvictions – because talking leftand acting right could be a contradictionbeyond redemption by2014 (the probable date <strong>of</strong> SouthAfrica’s next general election).P A G E 1 5

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Peter FranksP A G E 1 6Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Jabu Mbokazi

<strong>Limpopo</strong>’s very own medical training platformIT’S COMING AT LAST: A FULLMEDICAL SCHOOL IN POLOKWANEfFOR AT LEAST FIVE YEARS, THERE’S BEEN TALK OFTHE ESTABLISHMENT OF A TERTIARY HOSPITAL ANDMEDICAL SCHOOL IN LIMPOPO. IT’S OFFICIALLYBEING CALLED A NEW ‘HEALTH SCIENCESTRAINING PLATFORM’.The in-principle decision to embark upon thisdevelopment was bound up with the complexities <strong>of</strong>the merger between Medunsa in Gauteng and the old<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> the North. The process has beencomplicated by the involvement <strong>of</strong> the National andProvincial Departments <strong>of</strong> Education and theprovincial Department <strong>of</strong> Health, not to mention theaccommodation <strong>of</strong> the various interests in the twocampuses <strong>of</strong> the merged <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>. On thesurface, sometimes, the promise <strong>of</strong> new health andteaching facilities has seemed a distinctly on-<strong>of</strong>f affair.But this time it’s definite. Key preparations havestarted in earnest: the facilities are on the way. Hereare some <strong>of</strong> the basic facts.The whole project is mandated and supported bya national cabinet decision. A 600-bed hospital is tobe built at the Edupark campus in Polokwane. It’ll bea multistorey affair so as to limit the distancebetween departments. The cost will be in the region<strong>of</strong> R1,2-billion, and the hope is that construction willcommence later this year (2009). A detailedenvironmental impact study is already under way.But there’s a lot more to the project than this. In theplanning stage is the actual medical school buildingand <strong>of</strong> course residential blocks for staff and students.A delegation <strong>of</strong> university and provincial personnelwill be going to Australia and India soon to look atthe spatial relationship between hospitals and medicalschools in some <strong>of</strong> the newest developments <strong>of</strong> thiskind in the world.‘We’re looking for facilities here that are worldclass,’ says Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Peter Franks, the <strong>University</strong>’sDeputy Vice-Chancellor Academic and the Turfloopcampus principal. ‘We’re determined to make thePolokwane teaching platform the best we possibly can.’On behalf <strong>of</strong> the Vice-Chancellor, Franks chairs thetask team that has been established to co-ordinate thewide-ranging activities that are necessary to get thenew facilities <strong>of</strong>f the ground, as well as the teachingthat needs to take place for the facilities to be fullyand effectively utilised.The task team was established at a workshop thattook place last November and was attended byrepresentatives <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong> (fromTurfloop, Medunsa and the embryonic medical campusat the Polokwane Provincial Hospital), the <strong>Limpopo</strong>Provincial Department <strong>of</strong> Health and SocialDevelopment, as well as the <strong>Limpopo</strong> Office <strong>of</strong> thePremier and Provincial Treasury.The task team appointed several key committees t<strong>of</strong>acilitate the alignment <strong>of</strong> the vision <strong>of</strong> the Polokwanemedical training platform with various specialisedaspects <strong>of</strong> the university as a whole. These committeesdeal with curriculum issues, staffing requirements,logistics (including a full assessment <strong>of</strong> facilitiesrequired and a transport strategy that will link medicalstudents with the two provincial hospitals as well asthe Turfloop campus), and financial matters.The hope is that the first medical students –probably around 50 <strong>of</strong> them, but increasing forsubsequent annual intakes – will be registered at thestart <strong>of</strong> 2010. Of course, the new facilities won’t beready. They’ll start their studies in the sciencedepartments on the Turfloop campus and do theirclinical work (from year two) in the existing Polokwaneand Mankweng hospitals while the Health SciencesTraining Platform is being built.This projected 2010 commencement date is not amoment too soon for Dr Morwanphaga Nkadimeng,senior general manager <strong>of</strong> health care services in<strong>Limpopo</strong>’s Department <strong>of</strong> Health. ‘This country is desperatefor doctors,’ he asserts. ‘We simply can’t affordany more delays.’Nkadimeng supported his statement by pointing outthat South Africa had only 20 000 doctors registeredP A G E 1 7

<strong>Limpopo</strong>’s very own medical training platformIT’S COMING AT LAST: A FULL MEDICAL SCHOOL IN POLOKWANEwith the Health Pr<strong>of</strong>essionals Council, many <strong>of</strong> whomwere working overseas, and 12 000 <strong>of</strong> whom were inprivate practice.‘Now compare this with World Health Organisationguidelines that advise a doctor/population ratio <strong>of</strong>1:500. Even at 50 percent <strong>of</strong> the WHO ratio, SouthAfrica should have 45 000 doctors. But existingmedical schools are producing only a thousand newdoctors a year. Looked at from this perspective,the whole country is on the brink <strong>of</strong> a medicalcatastrophe. We in the poorer provinces are runningour health services on foreign nationals. Here in<strong>Limpopo</strong>, the need is desperate.’Franks said his steering committee was currentlyengaged in the preparation <strong>of</strong> a business plan forsubmission to the national Department <strong>of</strong> Educationwhich will be asked to fund the Medical School facilitiesto the tune <strong>of</strong> up to R1,5-billion over three years.The project is not without its difficulties, however.Nkadimeng talks forcefully about the need for the newmedical school to foster relationships and linkageswith top international medical universities. ‘It’s difficultto attract top academic staff to Polokwane,’ he says;‘and the job <strong>of</strong> getting people from other countriesin the south is definitely made no easier by theaccreditation rules <strong>of</strong> the Health Pr<strong>of</strong>essionals Council.But unless we unlock these particular doors – thosepertaining to international linkages and accreditation– it will be much more difficult to succeed.’Nevertheless, there is genuine enthusiasm for thePolokwane medical school project, and a determinationto face the challenges that the project presents.Franks points out that Polokwane is growing rapidlyand that it will become a big regional centre over time.‘The vision <strong>of</strong> the university is to be a top-class Africanuniversity solving African problems. My personalvision is that the Polokwane medical teaching platformwill become a regional African resource.’Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Jabu Mbokazi, 4 the Deputy Dean <strong>of</strong> HealthSciences who is running the embryonic medical schoolat Polokwane Hospital, told <strong>of</strong> a recent visit by Britishacademic Dr John Cookson, who had helped tolaunch the Hull/York Medical School in north-eastEngland five years ago. ‘He was favourablyimpressed,’ Mbokazi said. ‘He admitted that theDr Morwanphaga Nkadimengembryonic Polokwane facility was currently operatingwith more specialised staff than had been at it hisdisposal when he began with the Hull/York school.’Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Philip Venter, 5 the co-ordinator <strong>of</strong> theFaculty <strong>of</strong> Health Sciences on the Turfloop campus,makes no bones about his enthusiasm. ‘We have hugepotential here – for teaching and research,’ he says.‘We’re sitting right in the middle <strong>of</strong> SADC and we’rein the process <strong>of</strong> getting a state-<strong>of</strong>-the-art medicalschool and training hospital.’Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Errol Holland, 6 the newly appointedExecutive Dean <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong>’s Faculty <strong>of</strong> HealthSciences, says he firmly believes that the two medicaltraining platforms in his faculty will become worldleaders in developmental medicine. ‘In addition, we’llbecome the institution <strong>of</strong> choice for the most talentedteachers and most gifted students, particularly thosewith noble ideals to serve the most vulnerable.’We should allow Nkadimeng the last word.‘In 1956, a small hospital in Stellenbosch, against allthe odds, became a tertiary hospital. But the will tosucceed was there. Today that hospital is Tygerberg,one <strong>of</strong> South Africa’s largest tertiary teachinginstitutions. The will to succeed – in the provincialadministration and in the university – is now the mostimportant ingredient for us.’4 See the article on page 19 for more from Mbokazi. 5 See the article on page 20 for more from Venter.6 See pr<strong>of</strong>ile on page 21 for more on Holland.P A G E 1 8

<strong>Limpopo</strong>’s very own medical training platformWHAT’S ON THE GROUND ALREADY?We take a look at the existing postgraduate school forspecialist doctors operating out <strong>of</strong> Polokwane Hospital, andget an inkling <strong>of</strong> how this will dovetail into the full HealthSciences Training Platform <strong>of</strong> the future.bBEHIND THE SPRAWLING POLOKWANE HOSPITALSTANDS AN INCONSPICUOUS RED-BRICK BUILDINGTHAT CAN BE CONSIDERED THE EMBRYO FROMWHICH LIMPOPO’S FULL MEDICAL TEACHINGPLATFORM WILL GROW. At the gate there’s a signthat refers to the building as a satellite campus <strong>of</strong> the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>. Inside, there’s a thrivingpostgraduate school for the training <strong>of</strong> doctors in arange <strong>of</strong> specialities.‘In fact, we have twelve fully accrediteddepartments,’ says Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Jabu Mbokazi, who runsthe school. He is what is called a joint appointee,responsible simultaneously to the <strong>Limpopo</strong> Department<strong>of</strong> Health and the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>, where heholds the position <strong>of</strong> Deputy Director in the Faculty <strong>of</strong>Health Sciences.The fully accredited departments are currentlytraining specialists in Public Health Medicine;Psychiatry; Radiology; Radiation Oncology;Ophthalmology and Paediatrics (both these specialitiesare centred at Mankweng Hospital which is situatedclose to the Turfloop campus in Sovenga); Obstetricsand Gynaecology; Nuclear Medicine; ForensicPathology; Anatomical Pathology; and Family Medicine.There are also six partially accredited departments.This means that registrars train in Polokwane for twoyears before going elsewhere for their final years.Obviously, partial accreditation is a first step tobecoming fully accredited. The following departmentsare still in the ‘partial’ category: Emergency Medicine;Internal Medicine; General Surgery;Otorhinolaryngology (ear, nose and throat);Orthopaedics; and Anaesthesiology.‘In anybody’s language, that’s a thrivingpostgraduate school,’ says Mbokazi. ‘We are currentlytraining 60 registrars in the various programmes.The required specialist/student ratio is 1:2 (theexception is Emergency Medicine where the ratio is1:4) so you can see that a good number <strong>of</strong> specialistteachers have already been attracted to Polokwane.Other specialities soon to be incorporated into theschool are Cardiothoracic Surgery, and Plastic andReconstructive Surgery.’But will the school be ready to train ordinaryundergraduate doctors?Mbokazi explains the new teaching methodologyused in many leading medical schools and also to beemployed in Polokwane. After a first year <strong>of</strong> basicsciences, undergraduate students are exposed to aseries <strong>of</strong> medical ‘themes’ – for example, nutrition orthe digestive system or cardiovascular issues – intowhich many <strong>of</strong> the existing specialist departments willbe able to make useful inputs.‘We’ve visited many medical schools,’ Mbokaziexplains, ‘and spoken to many people. For example,we were recently visited by British medical academicDr John Cookson. He was instrumental in launchingthe Hull/York Medical School in north-east Englandfive years ago. He was favourably impressed by whathe found here in Polokwane. He admitted that ourfacility was currently operating with more specialisedstaff than had been at it his disposal when he beganwith the Hull/York school.’The probable pattern for the future would be tobuild the general undergraduate training platform atthe Polokwane and Mankweng hospitals, while thespecialist and sub-specialist departments, currentlyoperating out <strong>of</strong> these hospitals, would eventually becentred at the new hospital and medical schoolcomplex to be built on the Edupark campus.P A G E 1 9

<strong>Limpopo</strong>’s very own medical training platformTHE OTHER HALFExamining the process <strong>of</strong> developing a range <strong>of</strong> alliedhealth disciplines to enrich the training range <strong>of</strong> thePolokwane medical school.dDOCTORS AREN’T THE ONLY HEALTHPROFESSIONALS THAT THE COUNTRY NEEDS ALOT OF. Indeed, doctors would be hard-pressed tobe effective without the support <strong>of</strong> a whole range <strong>of</strong>disciplines that together make up the total healthcarepackage. So it wouldn’t make sense for a medicalfaculty, complete with the necessary sophisticatedtraining hospital, not to pay close attention to these‘non-medical’ or ‘allied health’ disciplines. Thesedisciplines constitute the other half <strong>of</strong> the medicalschool package planned for the special health campusadjacent to Edupark in Polokwane.The person charged with developing this side <strong>of</strong>things is Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Philip Venter, currently theco-ordinator <strong>of</strong> the Faculty <strong>of</strong> Health Sciences on theTurfloop campus. It would be difficult to find anyonemore motivated, and more in tune with the potential.Speaking about the prospects <strong>of</strong> a Health SciencesTraining Platform for <strong>Limpopo</strong> Province in 2005,Venter was quoted as saying that ‘the big opportunityis to develop one <strong>of</strong> the finest rurally-based trainingplatforms in the whole <strong>of</strong> the developing world’. 7Now he – and the whole <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong> province –have got the chance.To effect the necessary preparatory work, Venterhas already established an Allied Health DevelopmentTeam (AHDT) which has met on several occasions.An important innovation in Venter’s approach is tohave included non-academic clinical practitioners fromthe provincial health services in the team.The reason for this is straightforward. The alliedhealth disciplines already established in the Faculty<strong>of</strong> Health Sciences are optometry, pharmacy, nursing,nutrition, medical science and public health. These willform a useful base for the non-medical side <strong>of</strong> the newfaculty. But more departments will need to be added toachieve the vision <strong>of</strong> a full medical faculty for <strong>Limpopo</strong>.‘Our approach with regard to those departmentsthat do not currently exist,’ explains Venter, ‘is tobegin to build on the clinical services alreadyoperating in the province. These include radiography,speech therapy and audiology, physiotherapy,dentistry, and so on. So we have asked the staff fromthese services to help the AHDT to establishappropriate curricula for undergraduate degrees.Ultimately, <strong>of</strong> course, we’ll be talking masters anddoctoral degrees as well.’Venter says that this inclusion <strong>of</strong> existing clinicalservices staff has generated real enthusiasm for whatis happening in the province. This enthusiasmreinforces the feedback that Venter himself gave to theAHDT from the second faculty restructuring workshopheld earlier this year: that the Edupark health campuswill house a full school <strong>of</strong> allied health sciences.No fewer than 16 allied health departments areenvisaged. As well as the existing Turfloopdepartments and those to be developed from existingclinical services departments within the provincialhealthcare system, some brand new specialities arebeing considered. An example <strong>of</strong> this as the mooteddepartment <strong>of</strong> Kineseology (a branch <strong>of</strong> sportsmedicine for sports trainers, coaches, and physicaleducation in schools). Training in this last categorywill soon be in high demand because the Department<strong>of</strong> Education has agreed in principle to reintroducephysical education into government schools.‘We have huge potential here – for teaching andresearch in the allied health sciences,’ says Venter.‘We’re sitting right in the middle <strong>of</strong> SADC and we’rein the process <strong>of</strong> getting a state-<strong>of</strong>-the-art medicalschool and training hospital. That’s an appetisingcombination. It certainly augurs well for the future <strong>of</strong>the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>.’7 See <strong>Limpopo</strong> <strong>Leader</strong> 3 Autumn 2005, page 23.P A G E 2 0

Pr<strong>of</strong>ile: Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Errol HollandA COMPLEX AND CHALLENGINGTASKPr<strong>of</strong>ile follows on page 22.P A G E 2 1

Pr<strong>of</strong>ile: Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Errol HollandA COMPLEX AND CHALLENGING TASKaAT THE BEST OF TIMES, RUNNING A HEALTHSCIENCES FACULTY IS MORE THAN A FULL-TIMEJOB. Running one with two teaching platforms – inlayman’s parlance, with two full medical schools – isan almost unimaginably complex undertaking.Nevertheless, that’s what Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Errol Holland hastaken on. On 1 April this year, he started work as theExecutive Dean <strong>of</strong> the Faculty <strong>of</strong> Health Sciences at the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong>. This means that he’s in charge<strong>of</strong> the old Medunsa medical school on the university’sGa-Rankuwa campus and that he’ll be intimatelyinvolved with the establishment <strong>of</strong> the new medicalschool currently being established in Polokwane.That’s a huge AND. However, Holland very clearlysees what could easily be considered two distinct jobsas a single challenge.‘My top priority will be to integrate the oldMedunsa with the new Polokwane,’ he says. ‘We’reall part <strong>of</strong> a single institution. We have commongoals. Our joint mission is to serve the vulnerable.I want Medunsa to be proud <strong>of</strong> being part <strong>of</strong> thePolokwane initiative. I want Polokwane to work inclose association with the needs and aspirations <strong>of</strong>health service delivery in <strong>Limpopo</strong> province.’Brave words, particularly when they are soconsciously uttered against the backdrop <strong>of</strong> the stopstartmerger, <strong>of</strong>ficially established in January 2005,between the old <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> the North and Medunsa.Holland (now 61) knows what he’s talking about.Since September 2005, he’s served as the Strategicand Technical Manager in the <strong>of</strong>fice <strong>of</strong> the Chief <strong>of</strong>Operations in Gauteng’s Department <strong>of</strong> Health, andsubsequently the <strong>of</strong>fice <strong>of</strong> Special Advisor to the MECfor Health. During his period with Gauteng, he’s donesome extraordinary things. During a period <strong>of</strong>explosive labour unrest in 2006, he served ascaretaker CEO <strong>of</strong> the Dr George Mukhari Hospital(to which Medunsa is attached), when he was obligedto pick up a personal bodyguard each morning on hisway to work. Once again stepping into the breech,Holland found himself in charge <strong>of</strong> Gauteng’s ForensicPathology Service for several months. And he wasclosely involved in the complex process <strong>of</strong> therelocation <strong>of</strong> the Pretoria Academic Hospital to theultra-modern Steve Biko Academic Hospital facilities.Holland’s experience in the administration andservice delivery side <strong>of</strong> health, as well as his extensiveacademic experience, brings a genuine depth <strong>of</strong>understanding to his new job. He was a prominenthealth activist during South Africa’s struggle years.He helped to write the ANC’s health policy documentthat appeared in the early 1990s. He also has clearideas <strong>of</strong> where he wishes to take his twin-platformedfaculty.‘Since 1994, a lot has been said about declininghealthcare standards. Some <strong>of</strong> it is true. But the overallreality is that for the first time in the history <strong>of</strong> ourcountry every individual is now within walkingdistance <strong>of</strong> free primary health care. That’s a pricelessachievement. And it’s on that foundation that thefaculty should build its contribution. There’s areawakening <strong>of</strong> a larger social consciousness, notleast in health care and medical science. The<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong> is a part <strong>of</strong> this trend. It’sstated mission and vision fits us perfectly into thisglobal community that sees our common humanity asthe most valuable thing.’Holland was born in Johannesburg – both his parentswere teachers there – and did all his schooling inCoronationville. He then did two years <strong>of</strong> science atthe <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Western Cape before moving tothe <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Cape Town to train as a doctor. Hegraduated in 1972, returning to Johannesburg tocomplete his internship period at Coronation andBaragwanath hospitals. It was while working at thelatter that he completed a postgraduate specialistdegree in internal medicine, and then pursued hisinterest in the super-specialised field <strong>of</strong> ClinicalHaematology. He should have been transferredimmediately into the city’s only haematology unit atthat time, which was housed in the JohannesburgGeneral Hospital in Hillbrow.‘But I wasn’t allowed to work there,’ he said.When asked why, he smiled and pointed at the colour<strong>of</strong> his skin.Johannesburg’s loss was America’s gain. Hollandand his family moved to Washington DC where hehad been awarded a one-year fellowship at theGeorgetown <strong>University</strong> Medical Center. He thenmoved to the research institute <strong>of</strong> the American RedP A G E 2 2

Cross where for a further year he did advancedresearch on the adhesive properties <strong>of</strong> blood platelets,which served as the basis for his PhD that was subsequentlyawarded by the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Cape Town in1994.Back in South Africa, the political writing was onthe wall, and he had little difficulty in finding aposition in the haematology unit at Groote SchuurHospital in Cape Town. He served there for 14 yearsbefore being appointed as head <strong>of</strong> the School <strong>of</strong>Clinical Medicine at the Wits Medical School inJohannesburg. He also served as acting vice-dean <strong>of</strong>the Faculty <strong>of</strong> Health Sciences at that institution.From there he went to Gauteng Health; and nowhe’s facing what is arguably the biggest challenge <strong>of</strong>his career.‘It’s a very exciting challenge as well,’ he says.‘The opportunities are enormous. And I’ve no doubtthat we’ll be successful. The staff at Medunsa and in<strong>Limpopo</strong> are dedicated and motivated; and I believewe are ready to embrace our historic mission.’Holland described this ‘historic mission’ asresponding to the health and development needs <strong>of</strong>ordinary people. ‘The aims <strong>of</strong> the university’s arecorrect. To be a world-class African university thataddresses the needs <strong>of</strong> African communities throughinnovative ideas. To strive for excellence <strong>of</strong> research,teaching and community outreach, and to work handin glove with provincial, national and regionalauthorities within a developmental paradigm.’More specifically, Holland refers to the internationallyagreed Millenium Development Goals as the firsttargets for his new faculty. In particular he mentioneda renewed focus on the health <strong>of</strong> women and girls, areduction in child mortality, improved health care formothers and pregnant women; and more generally theeradication <strong>of</strong> hunger and poverty, the protection <strong>of</strong>living conditions and the environment, and the control<strong>of</strong> major epidemics, such as those <strong>of</strong> malaria,tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS.‘Success in these endeavours will guarantee thatwe produce high-quality graduates with the highestideals.’Holland returns repeatedly to the ethicalimperatives inherent in medicine. He talks withunderstanding <strong>of</strong> the rush <strong>of</strong> the previouslydisadvantaged to secure higher living standards forthemselves. But he notes that in the face <strong>of</strong> the newbusiness and managerial opportunities that havepresented in the country since 1994, medicine is nolonger the premier economic draw-card. ‘Hopefully,’he says, ‘this means that medicine will once againattract more people interested in social responsibility,in service to others, and in the developmental goals <strong>of</strong>the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Limpopo</strong> as a whole, all the facultiesworking in concert.’He speaks convincingly <strong>of</strong> the need for anentrenched partnership with the <strong>Limpopo</strong> provincialgovernment, and the symbiosis that will be necessarybetween health service provision and academichealth, and particularly between service challengesand research, ‘if we are to achieve our developmentalgoals’.In conclusion, Holland paints a picture <strong>of</strong> the futurein colours defined by his definition <strong>of</strong> the ultimate goalfor the Faculty <strong>of</strong> Health Sciences on the university’stwo campuses.‘In everything we do,’ he asserts, ‘we will optimisedevelopment – economic development, as well as thatpertaining to the physical, intellectual, social andspiritual spheres. We will become world leaders indevelopmental academic programmes. And we willbecome the institution <strong>of</strong> choice for the most talentedteachers and most gifted students, particularly thosewith noble ideals to serve the most vulnerable.’P A G E 2 3

CAMPUS WITH A PAST – PART TWOiIN THE PREVIOUS EDITION OF <strong>Limpopo</strong> <strong>Leader</strong>, WE STARTED A PEEK BACK INTO THE 30-ODD YEARS THAT MAKE UP THEHISTORY OF UL’S GA-RANKUWA CAMPUS, AND AT SOME OF THE HIGHS AND LOWS THAT HAVE HELPED TO SHAPE THISINSTITUTION THAT HAS NOT JUST SURVIVED, BUT THRIVED, MORE OFTEN THAN NOT AGAINST THE ODDS.In this review <strong>of</strong> our past, we look at the School <strong>of</strong> Dentistry from the perspective <strong>of</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Tshepo Gugushe, Director <strong>of</strong> theSchool, who has been at the university for about 20 years. We also speak to Dr AK Seedat, a part-time lecturer in dentistry anda past activist, who has interesting insights from his more than 25-year association with this campus.Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Len Karlsson, who joined Medunsa in 1980 as Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor in the Department <strong>of</strong> Community Health, andbecame Vice-Principal <strong>of</strong> Medunsa in 1986, recalls a several anecdotes that added spice – and <strong>of</strong>ten amusement – to his yearson the fifth floor.Our history is invaluable. As Mohandas Gandhi said, ‘A small body <strong>of</strong> determined spirits fired by an unquenchable faith in theirmission can alter the course <strong>of</strong> history.’ The key is <strong>of</strong> course the small body <strong>of</strong> determined spirits. Let’s meet some more <strong>of</strong> ours.P A G E 2 4

Campus with a pastSCHOOL OF DENTISTRY RISES HIGHABOVE MEDIOCRITYaA CURIOSITY. That’s how Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Tshepo Gugushe’swhite colleagues viewed him when he joined whatwas then Medunsa’s Faculty <strong>of</strong> Dentistry as a seniorspecialist in the Department <strong>of</strong> Community Dentistry inthe 1980s. He was the first black specialist to beappointed in the faculty – ‘and they watched closelyto see if I was up to it’, he recalls.Gugushe had left the relative ‘comfort’ <strong>of</strong> the<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Witwatersrand’s Dental School to joinMedunsa, which had been operating for about10 years – not many <strong>of</strong> which had been free <strong>of</strong>controversy. ‘Very few people could understand whyI made the move from Wits. It was considered to bea progressive environment; one where I could advancemy career, even as a black person in South Africaunder an apartheid government.’But for Gugushe that was not what it was about.He says that one <strong>of</strong> the reasons for coming toMedunsa was ‘to give back to what I perceived to bea predominantly black institution. I wanted to spendthe rest <strong>of</strong> my career in an environment that would<strong>of</strong>fer me spiritual enrichment’. And it has, he says. Ithas not always been an easy or comfortable ride, butit has been rewarding.It has also been a challenge, maintains Gugushe,who today holds the position <strong>of</strong> Director <strong>of</strong> the School<strong>of</strong> Dentistry on the university’s Ga-Rankuwa campus.The philosophy <strong>of</strong> life and value system that havekept Gugushe on his committed path were instilled inhim by his father and mother – a teacher and nurserespectively. Their mentorship, encouragement andguidance kept him fixed on his goals, even throughthe tough days in Soweto in the 70s and 80s.After completing his BSc degree at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong>Fort Hare, he was conditionally accepted intosecond year BDS at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> thePr<strong>of</strong>essor Tshepo GugusheP A G E 2 5