The Condition of Postmodernity 13 - autonomous learning

The Condition of Postmodernity 13 - autonomous learning The Condition of Postmodernity 13 - autonomous learning

190 Political-economic capitalist transformationmany share the sense that we are at some kind of 'second industrialdivide' (to appropriate the title of Piore and Sabel's book), and thatnew forms of labour organization and new locational principles areradically transforming the face of late twenti .eth-cent u. ry capitalis n: .The revival of interest in the role of small busIlless (a hIghly dynamIcsector since 1970), the rediscovery of sweatshops and of informalactivities of all kinds, and the recognition that these are playing animportant role in contemporary economic development even in themost advanced of industrialized countries, and the attempt to trackthe rapid geographical shifts in employment and economic fortune ,have produced a mass of information that seems to support thIsvision of a major transformation in the way late twentieth-centurycapitalism is working. A vast literature has indeed emerged, frmboth left and right ends of the political spectrum, that tends to depIctthe world as if it is in the full flood of such a radical break in allthese dimensions of socio-economic and political life that none ofthe old ways of thinking and doing apply any more.The second position sees the idea of flexibility as an 'extremelypowerful term which legitimizes an array of political practices' (ciflyreactionary and anti-worker), but without any str mg .empmcalor materialist grounding in the actual facts of orgamzatIon of latetwentieth-century capitalism. Pollert (1988), for example, factuallychallenges the idea of flexibility in labour markets and labour organization,and concludes that the 'discovery of the "flexible workforce"is part of an ideological offensive which celebrates pliability andcasualization, and makes them seem inevitable.' Gordon (1988)similarly challenges the idea of hyper- eograpical mobility fcapital as far beyond what the facts of IllternatlOnal trade (particularlybetween the advanced capitalist countries and the less developedcountries) will support. Gordon is particularly conc rned tocombat the idea of the supposed powerlessness of the nation state(and of worker movements operating within that framework) toexercise any degree of control over capital mobility. Sayer 198)likewise disputes the accounts of the new forms of accumulation IIInew industrial spaces as put forward by Scott (1988) and others onthe grounds that they emphasize relatively insignificant and peipheralchanges. Pollert, Gordon and Sa < er all argue .th .a there ISnothing new in the capitalist search for Illcresed flexlblhty or .locationaladvantage, and that the substantive eVIdence for any radIcalchange in the way capitalism is working is either weak or fa lty.Those who promote the idea of flexibility, they suggest, are eItherconsciously or inadvertently contributing to a climate of opinionan ideological condition - that renders working-class movementsless rather than more powerful.!1IFlexible accumulation 191I do not accept this position. The evidence for increased flexibility(sub-contracting, temporary and self-employment, etc.) throughoutthe capitalist world is simply too overwhelming to make Pollert'scounter-examples credible. I also find it surprising that Gordon, whoearlier made a reasonably strong case that the suburbanization ofindustry away from the city centres was in part motivated by adesire to increase labour control, should reduce the question ofgeographical mobility to a matter of volumes and directions of internationaltrade. Nevertheless, such criticisms introduce a number ofimportant correctives in the debate. The insistence that there isnothing essentially new in the push towards flexibility, and thatcapitalism has periodically taken these sorts of paths before, is certainlycorrect (a careful reading of Marx's Capital sustains the point).he .argument that there is an acute danger of exaggerating thesIgmficance of any trend towards increased flexibility and geographicalmobility, ?linding us to how strongly implanted Fordist productionsystems Ill are, deserves careful consideration. And the ideologicaland pohtIcal consequences of overemphasizing flexibility in thenarrow sense of production technique and labour relations are seriouseno t make .sober and careful evaluations of the degree offleXIbIlIty Imperative. If, after all, workers are convinced that capitalistscan move or shift to more flexible work practices even whenthey cannot, then the stomach for struggle will surely be weakened.But I think it equally dangerous to pretend that nothing has changed,when the facts of de industrialization and of plant relocation, of moreflexible manning practices and labour markets, of automation andproduct innovation, stare most workers in the face.The third position, which defines the sense in which I use the ideaof a transition from Fordism to flexible accumulation here, liessomewhere in between these two extremes. Flexible technologies andorganizational forms have not become hegemonic everywhere (butthen neither did the Fordism that preceded them). The current conjunctureis characterized by a mix of highly efficient Fordist production(often nuanced by flexible technology and output) in some sectorsand regions (like cars in the USA, Japan, or South Korea) and moretraditional production systems (such as those of Singapore, Taiwan,or Hong Kong) resting on 'artisanal,' paternalistic, or patriarchal(familial) labour relations, embodying quite different mechanismsof labour control. The latter systems have undoubtedly grown(even within the advanced capitalist countries) since 1970, often atthe expense of the Fordist factory assembly line. This shift hasimportant implications. Market coordinations (often of the subcontractingsort) have expanded at the expense of direct corporateplanning within the system of surplus value production and appro-

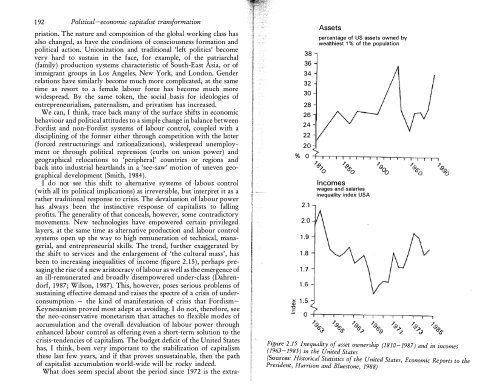

192 Political-economic capitalist transformationpriation. The nature and composition of the global working class hasalso changed, as have the conditions of consciousness formation andpolitical action. Unionization and traditional 'left politics' becomevery hard to sustain in the face, for example, of the patriarchal(family) production systems characteristic of South-East Asia, or ofimmigrant groups in Los Angeles, New York, and London. Genderrelations have similarly become much more complicated, at the sametime as resort to a female labour force has become much morewidespread. By the same token, the social basis for ideologies ofentrepreneurial ism, paternalism, and privatism has increased. .We can, I think, trace back many of the surface shifts in economicbehaviour and political attitudes to a simple change in balance betweenFordist and non-Fordist systems of labour control, coupled with adisciplining of the former either through competition with the latter(forced restructrings and rationalizations), widespread unemploymentor through political repression (curbs on union power) andgeographical relocations to 'peripheral' countries or regions andback into industrial heartlands in a 'see-saw' motion of uneven geographicaldevelopment (Smith, 1984).I do not see this shift to alternative systems of labour control(with all its political implications) as irreversible, but interpret it as arather traditional response to crisis. The devaluation of labour powerhas always been the instinctive response of capitalists to fallingprofits. The generality of that conceals, however, some contradictorymovements. New technologies have empowered certain privilegedlayers, at the same time as alternative production and labour controlsystems open up the way to high remuneration of technical, managerial,and entrepreneurial skills. The trend, further exaggerated bythe shift to services and the enlargement of 'the cultural mass', hasbeen to increasing inequalities of income (figure 2.15), perhaps presagingthe rise of a new aristocracy of labour as well as the eme(gence ofan ill-remunerated and broadly disempowered under-class (Dahrendorf,1987; Wilson, 1987). This, however, poses serious problems ofsustaining effective demand and raises the spectre of a crisis of underconsumption- the kind of manifestation of crisis that FordismKeynesianism proved most adept at avoiding. I do not, therefore, seethe neo-conservative monetarism that attaches to flexible modes ofaccumulation and the overall devaluation of labour power throughenhanced labour control as offering even a short-term solution to thecrisis-tendencies of capitalism. The budget deficit of the United Stateshas, I think, been very important to the stabilization of capitalismthese last few years, and if that proves unsustainable, then the pathof capitalist accumulation world-wide will be rocky indeed.What does seem special about the period since 1972 is the extra-38363432302826242220% 02.12.01.91.81.7x 1.5 -C1l"t:IcoAssetspercentage of US assets owned bywealthiest 1 % of the population70170777,9:.>.;7,9(96'Figu.re 2.15 Inequality of asset ownership (1810-1987) and in incomes(1963-1985) in the United States(Souces: Historical Statistics of the United States, Economic Reports to thePresldent, Harrison and Bluestone, 1988)

- Page 49 and 50: 88 The passage from modernity to po

- Page 51 and 52: 92 The passage from modernity to po

- Page 53 and 54: 96 The passage from modernity to po

- Page 55 and 56: 100 The passage from modernity to p

- Page 57 and 58: 104 The passage from modernity to p

- Page 59 and 60: 108 The passage from modernity to p

- Page 61 and 62: 112 The passage from modernity to p

- Page 63 and 64: 116 The passage from modernity to p

- Page 65 and 66: 7IntroductionIf there has been some

- Page 67 and 68: 124 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 69 and 70: 128 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 71 and 72: 132 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 73 and 74: 136 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 75 and 76: 140 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 77 and 78: From Fordism to flexible accumulati

- Page 79 and 80: 12 10Ql+-'l:'+-' 8CQlE>E 6Cl.EQlC4Q

- Page 81 and 82: 152 political-economic capitalist t

- Page 83 and 84: 156 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 85 and 86: 160 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 87 and 88: 164 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 89 and 90: 168 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 91 and 92: 172 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 93 and 94: 176 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 95 and 96: 180 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 97 and 98: 184 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 99: 188 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 103 and 104: 196 Political-economic capitalist t

- Page 105 and 106: 12IntroductionMarshall Berman (1982

- Page 107 and 108: 204 The experience of space and tim

- Page 109 and 110: 208 The experience of space and tim

- Page 111 and 112: 212tThe experience of space and tim

- Page 113 and 114: 216 The experience of space and tim

- Page 115 and 116: Table 3.1 A 'grid' of spatial pract

- Page 117 and 118: TypeEnduringtimeDeceptivetimeErrati

- Page 119 and 120: I228 The experience of space and ti

- Page 121 and 122: 232 The experience of space and tim

- Page 123 and 124: 236 The experience of space and tim

- Page 125 and 126: 15The time and space of theEnlighte

- Page 127 and 128: 244 The experience of space and tim

- Page 129 and 130: Plate 3 5 Dynasty versus the map: t

- Page 131 and 132: 252 The experience of space and tim

- Page 133 and 134: Time and space of the Enlightenment

- Page 135 and 136: The rise of modernism as a cultural

- Page 137 and 138: 264 The experience of space and tim

- Page 139 and 140: 268 The experience of space and tim

- Page 141 and 142: 272 The experience of space and tim

- Page 143 and 144: 276 The experience of space and tim

- Page 145 and 146: 280 The experience of space and tim

- Page 147 and 148: 17Time-space compresson and thepost

- Page 149 and 150: 288 The experience of space and tim

192 Political-economic capitalist transformationpriation. <strong>The</strong> nature and composition <strong>of</strong> the global working class hasalso changed, as have the conditions <strong>of</strong> consciousness formation andpolitical action. Unionization and traditional 'left politics' becomevery hard to sustain in the face, for example, <strong>of</strong> the patriarchal(family) production systems characteristic <strong>of</strong> South-East Asia, or <strong>of</strong>immigrant groups in Los Angeles, New York, and London. Genderrelations have similarly become much more complicated, at the sametime as resort to a female labour force has become much morewidespread. By the same token, the social basis for ideologies <strong>of</strong>entrepreneurial ism, paternalism, and privatism has increased. .We can, I think, trace back many <strong>of</strong> the surface shifts in economicbehaviour and political attitudes to a simple change in balance betweenFordist and non-Fordist systems <strong>of</strong> labour control, coupled with adisciplining <strong>of</strong> the former either through competition with the latter(forced restructrings and rationalizations), widespread unemploymentor through political repression (curbs on union power) andgeographical relocations to 'peripheral' countries or regions andback into industrial heartlands in a 'see-saw' motion <strong>of</strong> uneven geographicaldevelopment (Smith, 1984).I do not see this shift to alternative systems <strong>of</strong> labour control(with all its political implications) as irreversible, but interpret it as arather traditional response to crisis. <strong>The</strong> devaluation <strong>of</strong> labour powerhas always been the instinctive response <strong>of</strong> capitalists to fallingpr<strong>of</strong>its. <strong>The</strong> generality <strong>of</strong> that conceals, however, some contradictorymovements. New technologies have empowered certain privilegedlayers, at the same time as alternative production and labour controlsystems open up the way to high remuneration <strong>of</strong> technical, managerial,and entrepreneurial skills. <strong>The</strong> trend, further exaggerated bythe shift to services and the enlargement <strong>of</strong> 'the cultural mass', hasbeen to increasing inequalities <strong>of</strong> income (figure 2.15), perhaps presagingthe rise <strong>of</strong> a new aristocracy <strong>of</strong> labour as well as the eme(gence <strong>of</strong>an ill-remunerated and broadly disempowered under-class (Dahrendorf,1987; Wilson, 1987). This, however, poses serious problems <strong>of</strong>sustaining effective demand and raises the spectre <strong>of</strong> a crisis <strong>of</strong> underconsumption- the kind <strong>of</strong> manifestation <strong>of</strong> crisis that FordismKeynesianism proved most adept at avoiding. I do not, therefore, seethe neo-conservative monetarism that attaches to flexible modes <strong>of</strong>accumulation and the overall devaluation <strong>of</strong> labour power throughenhanced labour control as <strong>of</strong>fering even a short-term solution to thecrisis-tendencies <strong>of</strong> capitalism. <strong>The</strong> budget deficit <strong>of</strong> the United Stateshas, I think, been very important to the stabilization <strong>of</strong> capitalismthese last few years, and if that proves unsustainable, then the path<strong>of</strong> capitalist accumulation world-wide will be rocky indeed.What does seem special about the period since 1972 is the extra-38363432302826242220% 02.12.01.91.81.7x 1.5 -C1l"t:IcoAssetspercentage <strong>of</strong> US assets owned bywealthiest 1 % <strong>of</strong> the population70170777,9:.>.;7,9(96'Figu.re 2.15 Inequality <strong>of</strong> asset ownership (1810-1987) and in incomes(1963-1985) in the United States(Souces: Historical Statistics <strong>of</strong> the United States, Economic Reports to thePresldent, Harrison and Bluestone, 1988)