English Language Teaching in its Social Context

English Language Teaching in its Social Context

English Language Teaching in its Social Context

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

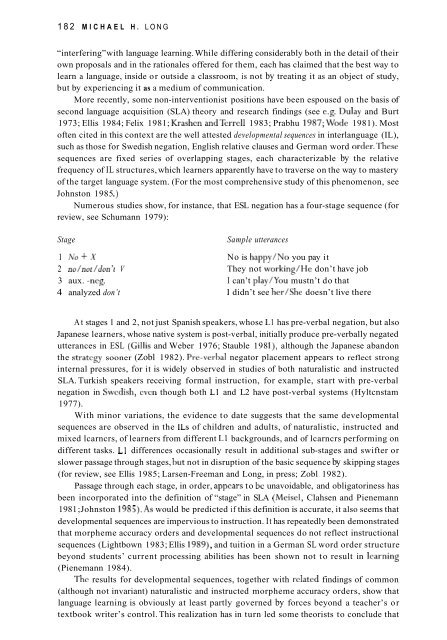

182 MICHAEL H. LONG“<strong>in</strong>terfer<strong>in</strong>g” with language learn<strong>in</strong>g. While differ<strong>in</strong>g considerably both <strong>in</strong> the detail of theirown proposals and <strong>in</strong> the rationales offered for them, each has claimed that the best way tolearn a language, <strong>in</strong>side or outside a classroom, is not by treat<strong>in</strong>g it as an object of study,but by experienc<strong>in</strong>g it as a medium of communication.More recently, some non-<strong>in</strong>terventionist positions have been espoused on the basis ofsecond language acquisition (SLA) theory and research f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs (see e.g. Dulay and Burt1973; Ellis 1984; Felix 1981; Krashcn andTerrel1 1983; Prabhu 1987;Wode 1981). Mostoften cited <strong>in</strong> this context are the well attested developmental sequences <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terlanguage (IL),such as those for Swedish negation, <strong>English</strong> relative clauses and German word order.Thesesequences are fixed series of overlapp<strong>in</strong>g stages, each characterizable by the relativefrequency of IL structures, which learners apparently have to traverse on the way to masteryof the target language system. (For the most comprehensive study of this phenomenon, seeJohnston 1985 .)Numerous studies show, for <strong>in</strong>stance, that ESL negation has a four-stage sequence (forreview, see Schumann 1979):Stage1 NofX2 no/not/don’t V3 aux. -ncg.4 analyzed don’tSample utterancesNo is happy/No you pay itThey not work<strong>in</strong>g/He don’t have jobI can’t play/You mustn’t do that1 didn’t see her/She doesn’t live thereAt stages 1 and 2, not just Spanish speakers, whose L1 has pre-verbal negation, but alsoJapanese learners, whose native system is post-verbal, <strong>in</strong>itially produce pre-verbally negatedutterances <strong>in</strong> ESL (Gillis and Weber 1976; Stauble 198 l), although the Japanese abandonthe 3tratcgy sooner (Zobl 1982). Pre-verbal negator placement appears to reflect strong<strong>in</strong>ternal pressures, for it is widely observed <strong>in</strong> studies of both naturalistic and <strong>in</strong>structedSLA. Turkish speakers receiv<strong>in</strong>g formal <strong>in</strong>struction, for example, start with pre-verbalnegation <strong>in</strong> Swcdish, even though both L1 and L2 have post-verbal systems (Hyltcnstam1977).With m<strong>in</strong>or variations, the evidence to date suggests that the same developmentalsequences are observed <strong>in</strong> the ILs of children and adults, of naturalistic, <strong>in</strong>structed andmixed lcarncrs, of learners from different L1 backgrounds, and of lcarncrs perform<strong>in</strong>g ondifferent tasks. L1 differences occasionally result <strong>in</strong> additional sub-stages and swifter orslower passage through stages, but not <strong>in</strong> disruption of the basic sequence by skipp<strong>in</strong>g stages(for review, see Ellis 1985; Larsen-Freeman and Long, <strong>in</strong> press; Zobl 1982).Passage through each stage, <strong>in</strong> order, appears to be unavoidable, and obligator<strong>in</strong>ess hasbeen <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong>to the def<strong>in</strong>ition of “stage” <strong>in</strong> SLA (Meisel, Clahsen and Pienemann1981 ;Johnston 1985).As would be predicted if this def<strong>in</strong>ition is accurate, it also seems thatdevelopmental sequences are impervious to <strong>in</strong>struction. It has repeatedly been demonstratedthat morpheme accuracy orders and developmental sequences do not reflect <strong>in</strong>structionalsequences (Lightbown 1983; Ellis 1989), and tuition <strong>in</strong> a German SL word order structurebeyond students’ current process<strong>in</strong>g abilities has been shown not to result <strong>in</strong> lcarn<strong>in</strong>g(Pienemann 1984).The results for developmental sequences, together with related f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of common(although not <strong>in</strong>variant) naturalistic and <strong>in</strong>structed morpheme accuracy orders, show thatlanguage learn<strong>in</strong>g is obviously at least partly governed by forces beyond a teacher’s ortextbook writer’s control. This realization has <strong>in</strong> turn led some theorists to conclude that