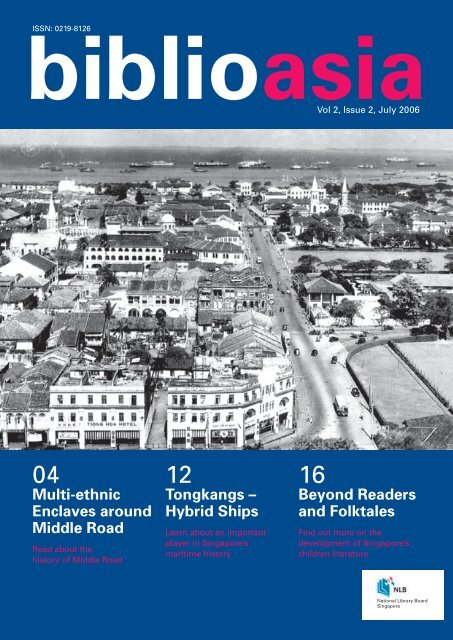

Multi-ethnic Enclaves around Middle Road - National Library ...

Multi-ethnic Enclaves around Middle Road - National Library ...

Multi-ethnic Enclaves around Middle Road - National Library ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

| FEATURE | | FEATURE |18 th centuries, the local Japanesecommunity heralds its first settler asOtokichi Yamamoto, who migratedto Singapore in 1862 and who diedhere in 1867 (Mikami, 1998:14-21). UtaMatsuda, the first female Japanesesettler, ran a grocery shop with herChinese husband in the 1860s. Withthe establishment of a trade consulatein 1879, an embassy in 1889, theintroduction of the Japanese-madejinrickshaw in 1884 and setting up ofJapanese shops and companies, thecommunity increased substantiallyby the close of the 19 th century. Atthe end of the Taisho period or thebeginning of the 20 th century, it wasestimated that 6,950 Japanese wereresiding in Singapore and Malaya(Mikami, 1998:26-7).The development of the Japaneseenclave in Singapore is connectedto the establishment of brothels eastof the Singapore River. No Japanesebrothels were in operation in 1868,but by the turn of the century, thegroup of brothels located alongHylam, Malabar, Malay and BugisStreets had displaced the earlierbrothel district in the Kampong Glamarea operated by Malays and laterby Chinese and Europeans (Warren,1993:44-46). Unlike the Chinesebrothels in Kreta Ayer area, whichserved only Chinese clients anddifferentiated into class types,Japanese brothels rarely discriminatedagainst patrons on the basis of<strong>ethnic</strong>ity, but were similarly dividedinto “higher and lower grade” houses(Warren, 1993: 50-51). The “success”of the brothels in the Southeast Asianregion was followed by the migrationof merchants, shopkeepers, doctorsand bankers to bolster the economyof a country yet unable to competeglobally as a modern industrialnation. Indeed, with the abolitionof prostitution in Singapore in 1920,these trades replaced the brothel“business” and sustained thecommunity that by then had its ownnewspaper (Nanyo Shimpo, 1908), acemetery (1911), a school (1912) anda clubhouse (1917) (Mikami, 1998:22-3). By 1926, the Japanese communityin Singapore had grown to occupythe area bound roughly by PrinsepStreet, Rochore <strong>Road</strong>, North Bridge<strong>Road</strong> and <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Road</strong>, alongsidethe Hainanese and other enclaves.<strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Road</strong>, which connected theMount Sophia area to the sea, wasknown to the community as ChuoDori or Central Street. The Japaneseprostitutes dubbed Malay StreetSuteretsu, a transliteration of theEnglish word “street”, and this wascontrasted with another “Japanese”area known as Gudangu (from“godown”), located near the mouthof the Singapore River and CollyerQuay, where Japanese shippinglines had established offices andagencies (Mikami, 1998:28-29). Likethe Hainanese, the Japanese createdtheir own system of street names,layered over or corrupting officialBritish ones.Built Forms in the <strong>Enclaves</strong>On both sides of the SingaporeRiver, shophouses were the mainform of residential and commercialbuildings to accommodate themigrants and settlers as well astheir trades. While their originand accompanying architecturalstyles are of some conjecture, theuse and design of the shophousewere also regulated by the dictatesof the 1822 Town Plan. 19 Raffles’instructions to the Town PlanningCommittee indicated that “allhouses constructed of brick ortile should have a uniform type offront, each having a verandah ofa certain depth, open at all timesas a continuous and coveredpassage on each side of the street”(Lee, 1984:7; Hancock, 1986:21).Besides sheltering pedestriansfrom inclement weather with theverandah (known as the five-footway), the mandated co-ordinationof these built forms also enabledthe provision of collective sanitaryservices like drainage and wastedisposal, and of course, permittedease of administrative control.The ordained use of brick provedto be practical, as it reduced therisk of fire to the residential andcommercial districts. Elsewhere inthe Straits Settlements, severe firesdestroyed areas in Georgetownin 1808, 1812, 1813, 1818 due tothe use of non-permanent andcombustible materials, and a majorfire almost burnt down the entiretown of Kuala Lumpur in 1881(Tjoa-Bonatz, 1998:126). The useof the covered five-foot way forshophouses was only implementedgradually in Penang in 1849 20 andlater in the states of Selangor (1890),and Perak (1893) (Lim, 1993:50-51).These two- or three-storeyedbuildings generally provided spacefor commercial activity at thepedestrian level and residentialspace above it, and were separatedby structural, brick party walls.The width of each shophouse waslimited by available spans of thetimber floor and roof beams atabout six metres, and the linearinterior spaces were punctuatedwith air wells for light andventilation. The brick and plasterfaçades accommodated simpletimber-louvred windows as wellas doors set within pilasters andother ornaments like architravesand mouldings. Local architecturalhistorian Lee Kip Lin suggestedthat the ornamentation found onearly shophouses were Chineseas evidenced by those in Malacca,but by the turn of the centurythese had transferred from “pureChinese” to a lavish application ofEuropean classical details. 21 Theefficacy of the building type was toensure its continued constructionup till the 1940s in Singaporeand Malaysia, while undergoingdifferent “style” and functionaladaptations.While physically similar, theuse of shophouses within theHainanese and Japanese enclavesdiffered from those on the otherside of the Singapore River. Asa minor enclave, the Hainanesehad to accommodate residential,communal as well as commercialfunctions within a smaller districtarea, with fewer shophouses.Unlike those clan associationsat Club Street occupying entireshophouses, the large numberof Hainanese clan associationswas housed predominantly in theupper storeys, with the space at theground-level reserved for remittanceservices, restaurants, and coffeeshops etc. One could sometimesfind multiple clan associationsand businesses occupying thesame ophouse, as two or morebusinesses may share the sameground-level shop space, andtwo or more clans may sharespaces above ground level. WongChin Soon, an enclave resident,recounted that of the 20 or soremittance companies that werefound along Purvis Street, manydoubled up as drapers, printers,shiphandling services, umbrellamakers, confectioneries, andhotels (Wong, 1989:309). Withthe decanting of its residentsin the 1980s, most of the clanassociations have remainedin the vicinity although theuses for ground level shopshave changed.Either as brothels or businesses, thepre-war Japanese also convertedinterior spaces of shophouses forfunctions relevant to their use,with attention to Japanese culturaland business practices. A 1910description of the Suteretsu by ananonymous reporter is as follows:“Around nine o’clock I went to seethe infamous Malay Street. Thebuildings were constructed in awestern style with their facadespainted blue. Under the verandahhung red gas lanterns with numberssuch as one, two, or three, andwicker chairs were arrangedbeneath the lanterns. Hundredsand hundreds of young Japanesegirls were sitting on the chairscalling out to passers-by, chattingand laughing… most of them werewearing yukata of striking colours”. 22The spaces on the upper floors ofthe brothels were segmented intorooms or cubicles, but denotedby tatami sizes. Unlike those inthe Kreta Ayer area, the Japanesebrothels averaged six tatami matsin size, housed less women, andwere thus more spacious. 23 Thegeneral functions of the shophousewere inverted: the upper floorswere used for “business” while theground level spaces were used asdwellings, waiting areas or offices.Rudimentary services included acommon bathroom on each floorand a kitchen at the back of thehouse. When prostitution wasabolished in 1920, these shophousesreturned to commercial or otheruses at ground level.An example of a business space,for which records still exist, wasthe Echigoya draper that had itspremises at <strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Road</strong> (Mikami,1998:36-41 & 82-95). In its 1908shop, textiles and clothing werestored in full-height timber cabinetsThe interiors of the Echigoya draper in 1908. Image courtesy ofthe Japanese Association of Singapore.that ran along the lengths of theground level walls, accentuating thelinear space (see picture). On onelength side a raised platform is alsoconstructed, known as the koagari,where customers would sit whilethey examine the merchandise. Forthe sake of non-Japanese patrons,a circular marble table and chairswere also provided. When it moveddown the road in 1928 to occupytwo adjoining shophouses; theopen, uncluttered aesthetic wasmaintained although waist-hightimber-framed and glass-panelleddisplay cabinets were used toenable customer circulation <strong>around</strong>the wares.<strong>Multi</strong>-<strong>ethnic</strong> Societies –Past and PresentThe Japanese community wasrepatriated after the end of WorldWar II, and for the subsequentfour years, no Japanese personwas allowed entry into Singapore(Gubler, 1972:130). The enclavebecame dilapidated by the endof the 1980s and many of itsshophouses have since beendemolished. In the early 1990s,a Japanese developer leased theplot of land where the brotheldistrict used to be and reconstructedmost of the shophouses, addingglass roofs over the internal streetsto create the first air-conditioned,“open-to-sky shopping arcade”in Singapore. Its new designationas Bugis Junction returnedthe spaces to commercial useand “reincarnated” the earliershophouses, but by its very act ofnaming, the area’s earlier multi<strong>ethnic</strong>histories were subjugated.In Contesting Space in ColonialSingapore, local geographerBrenda Yeoh argued that theexistence of different systemsof street names attested tocompeting representations of theurban landscape by its differentcommunities rather than theacceptance of a municipallyimposedone (Yeoh, 2003:219-235).The use of their own designationsfor places and streets by theHainanese and Japanese, asdiscussed above, confirms08 09

| FEATURE | | FEATURE |NotesPurvis Street with new ground-level shops and restaurants. Image courtesy of Lai Chee Kien.1 J. Kathirithamby-Wells, 1969: 50-51.Also F.G. Stevens, 1929: 385. Raffles hadsuggested to his superiors that this manner ofadministration should be implemented for allBritish colonies in Southeast Asia.2 Town Planning Committee, as quoted inHancock, 1986:16.3 Lee Kip Lin noted that Raffles formulated hisplan to divide the town into “neighbourhoods”or “campongs” as early as his second visit toSingapore in June 1819. From Lee, 1988:17.4 J.R. Logan, “Notices of Singapore”, Journalof the Indian Archipelago, 1854, as quoted inHodder, 1953:27.5 The Chinese were moved inland in1822 to establish a “principal mercantileestablishment” on the tongue of land adjacentto the river. From Lee, 1988:19.6 Farquhar’s residency was at the foot of thehill near the river, at a corner of High Street.Lee, 1988:149.7 This building, subsequently bought by thegovernment, was extended as a courthousein 1874 by J.F.A. McNair and then as aparliament house in 1954 by T.H.H. Hancockof the Public Works Department. FromHancock,1986:22-29.8 The land where Scott’s house stood wasacquired to build Raffles Hotel by the Sarkiesbrothers. Lee, 1988:148-149.9 There are also pockets of settlements ofCantonese-Hakka groups although the KretaAyer area is generally acknowledged as a“Cantonese” area.9 There are also pockets of settlements ofCantonese-Hakka groups although the KretaAyer area is generally acknowledged as a“Cantonese” area.10 Gambier farming employed shiftingcultivation, and was destructive as forests werecleared for fuel to boil the gambier leaves.Lee Kip Lin noted that there were about 5,000acres of gambier and pepper plantationsowned mainly by the Chinese by 1841. Healso noted that Europeans were moving to the“countrysides” as early as 1822, with JamesPearl occupying Pearl’s Hill in 1822 and CharlesRyan in Duxton Hill in 1827. From Lee, 1984:1.11 In contemporary descriptions of Singaporeby academics and laypersons, Chinatownis acknowledged only by the area on thesouthwestern areas of the river. The indicationof a “second” Chinatown can be seen on a mapreproduced by Hodder, 1953, Fig. 5 on p. 31.12 A 1953 map shows that the enclave mayhave “expanded” in the northwest direction upto Bencoolen Street. Hodder, 1953:3513 The trade was in wax, tiles, shoes,umbrellas, paper, dried goods and Chinesemedicinal herbs. Chan, 1976:48.14 They were “noted as waiters, cooks anddomestic servants …,”in Hodder, 1953:34.This was also discussed in Chan, 1976:48.15 From a 1976 address/telephone list providedin Chan, 1976:209-296, I counted 19 coffeeshops/restaurants and 6 hotels withinthe enclave.16 The restaurant was so famous that onecan still find chicken rice stalls throughoutSingapore and Malaysia bearing the similarname “Swee Kee chicken rice”. The originalrestaurant was located at Nos. 51-53,<strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Road</strong>, recently demolished. Wong,1992:51-60.17 This was No. 6, Malabar Street. Like othercoastal Chinese, the main deity for this templewas Ma Chor (or Tian Hou), goddess of safepassage at sea. Chan, 1976:9.18 Compiled from a 1976 address/telephonelist provided in Chan, 1976:209-296. Thesesmaller clan associations, located mainly inSeah Street were started after 1920 when theban on immigrant Hainanese women waslifted in China.19 Both Jon S. H. Lim and Mai Lin Tjoa-Bonatzhave discussed the possible origins of theshophouse in Southeast Asia, as a form thatmay have predated European arrival and havehad accumulative influences since the 15thcentury. Lim, 1993 and Tjoa-Bonatz, 1998.20 Conversation with Jon S. H. Lim, 11November 2003.21 It was also likely that European or localarchitects were beginning to engage inthe design of shophouses, abetted by theavailability of pattern books. Lee, 1984:7-8.22 As cited in Warren, 1993:41.23 Warren, 1993:52. He noted that there were5-7 prostitutes in a Japanese brothel comparedto 15-18 in Chinese brothels in Chinatown, p. 47.this argument. We may furtherobserve that the original municipalnaming of streets within that areaas “Malay”, “Malabar”, “Bugis”, and“Hylam,” had only captured thesettlement image at one particularmoment of Singapore’s colonialhistory. The subsequent occupationby other sub-groups along thosestreets and the changing sub-groupenclave boundaries or edges (ifthey existed) showed the failure ofcolonial mapping and naming along<strong>ethnic</strong> constituencies.Hylam Street (Hylam: a transliterationof “Hainan”) was named for theearly Hainanese settlers that lived<strong>around</strong> Malabar Street. No streetwas named for the Japanesecommunity that settled later alongthe same streets. By the time theJapanese enclave was taking shapethere, the Hainanese community hadmoved from Hylam Street to theBeach <strong>Road</strong> area to capitalise onsea frontage and pier facilities.Ironically, Hylam Street itself waslater called Japan Street by theHainanese community after theyhad moved out as a subsequentrendering of that space. Themunicipality, however, did not renamethe streets to register the changing<strong>ethnic</strong> complexion of the area.The spatial and built forms of thetwo communities, as discussed, alsoshowed the difficulty of generalisingor characterising the nature of suchenclaves as well as their built forms– especially shophouses whichhave been described in extantacademic and official literatureas “ubiquitous”. The builders andoccupants of shophouses <strong>around</strong><strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Road</strong> adapted them to suitthe extant social and economicconditions they faced, anddemonstrated the flexibility of suchforms by converting their use whenconditions changed or were altered.The shophouse spaces <strong>around</strong><strong>Middle</strong> <strong>Road</strong> served the needsof not only their own respectivecommunities, but also with regardto and in consideration of other<strong>ethnic</strong> sub-group members residing<strong>around</strong> it. Such uses by different<strong>ethnic</strong> groups represent importantaspects of multi-<strong>ethnic</strong> communityformation and living in Singapore,or at least that, which is found in theSmaller Town.By describing the history ofenclaves and built-forms of thesetwo sub-groups, I have privilegedtheir discussion over the othergroups that co-existed in Xiao Bo,the Smaller Town, and those inother areas of colonial Singapore.My attempts to discuss what Icalled “multi-<strong>ethnic</strong> enclaves” arelimited to the available texts andexpressions of these two groups.This is not intentional, and it ishoped that by beginning with twoof them, a sketch of the urbanhistory of the area between theSingapore and Rochore rivers maymaterialise eventually with the helpof other scholars and researchers.It is also hoped that this essayserves in a small way towards thewriting of Singapore’s larger multi<strong>ethnic</strong>history that may be clarifiedwhen the nature of its constituentforms are further discussed andmade available.ReferencesBraddell, R. (1934). The lights of Singapore.London: Metheun & Co. Ltd.Chan, S. K. (1976). The Hainanese commercial& industrial directory, Republic of SingaporeVol. 2. Singapore: Hainanese Association ofSingapore.Gubler, G. (1972). The pre-Pacific WarJapanese community in Singapore.Unpublished M.A. Thesis submitted to BrighamYoung University.Hancock, T. H. H. (1986). Coleman’s Singapore.Monograph No. 15 of the Malaysian Branchof the Royal Asiatic Society. Kuala Lumpur:MBRAS.Call No.: RSING q720.924 COL.HHodder, B. W. (1953). Racial groupings inSingapore. The Malayan Journal of TropicalGeography, 1. Singapore: Department ofGeography, University of Malaya in Singapore.Call No.: RDTYS 910.0913 JTG v. 1Kathirithamby-Wells, J. (1969). Early Singaporeand the inception of a British administrativetradition in the Straits Settlements (1819– 1832). Journal of the Malayan Branch, RoyalAsiatic Society, 42(2), 48-73. Kuala Lumpur:MBRAS.Call No.: RCLOS v.42 1969 959.5 JMBRAS v. 42Lee, K. L. (1984). Emerald Hill: The story ofa street in words and pictures. Singapore:<strong>National</strong> Museum.Call No.: RSING q959.57 LEE-[HIS]Lee, K. L. (1988). The Singapore house 1819– 1942. Singapore: Times Editions.Call No.: RSING 728.095957 LEELee, K. Y. (1998). The Singapore story: Memoirsof Lee Kuan Yew. Singapore: Times Editions.Call No.: RSING English 959.57 LEE-[HIS]Lim, J. S.H. (1993). The shophouse Rafflesia:An outline of its Malaysian pedigree and itssubsequent diffusion in Asia. Journal of theMalayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society, 66(1),47-66. Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS.Call No.: RSING v66 i1 93 959.5 JMBRAS v.66pt.1Mikami, Y. (Ed.). (1998). Prewar Japanesecommunity in Singapore: Picture and record.Singapore: The Japanese Association,Singapore.Call No.: RSING English 305.895605957 PREMills, L. A., & Turnbull. C. M. (Ed.). (Circa 1867).British Malaya 1824-67. Journal of the MalayanBranch, Royal Asiatic Society, 33(3), 36-85.Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS.Call No.: RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS v. 33pt3Stevens, F. G. (1929). A contribution to the earlyhistory of the Prince of Wales Island. Journalof the Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society,7(3), 377-414. Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS.Call No.: RRARE v.7 1929 959.5 JMBRAS v. 7Tan, B. L. (Ed.). 1986. History of the Chineseclan associations in Singapore. Singapore:Singapore Federation of Chinese ClanAssociations.Call No.: RSING q959.57 HIS-[HIS]Tjoa-Bonatz, M. L. (1998). Ordering of housingand the urbanisation process: Shophousesin Colonial Penang. Journal of the MalayanBranch, Royal Asiatic Society, 71(2), 123-136.Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS.Call No.: RSING 959.5 JMBRAS v. 71Warren, J. F. (1993). Ah Ku and Karayukisan:Prostitution in Singapore 1840 – 1940.Singapore: Oxford University Press.Wong, C. S. (1989). Kiung Chow Hwee Kuan135th anniversary souvenir magazine.Singapore: Singapore Kiung Chow Hwee Kuan.Wong, C. S. (1992). Roots the series #3. Singapore:Seng Yew Book Store and Shin Min News Daily.Yeoh, B. S. A. (2003). Contesting space incolonial Singapore: Power relations and thebuilt environment. Singapore: SingaporeUniversity Press.Call No.: RSING 307.76095957 YEO10 11

| FEATURE | | FEATURE |Tongkangs: Hybrid Ships in a Moment ofSingapore’s Maritime HistoryBy Ngiam Tong Dow, based on a university dissertation ca. 1957; Edited by Aileen LauCaptions and images reproduced from Maritime Heritage of SingaporeThe history of the tongkang industryin Singapore is part of the historyof enterprise in Southeast Asia.The history of the industry beganwith Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819.As soon as Raffles laid down thecommercial foundations of theisland, merchants <strong>around</strong> theregion and beyond arrived andbegan operating from this rapidlyexpanding centre of trade. TheSingapore merchants acted as theagents of exporters in China, sellingon their behalf, the produce, mainlyfoodstuffs, of the coastal provincesof South China – Fujian, Guangdongand Hainan Island. The main portsfor this export trade were Amoy,Swatow (Shandou today), and HoiHow, the capital of Hainan.Access to tongkang mooringsby sampan.During the 19 th and early 20 th centuries,there were relatively few steamships,so that the main part of the tradebetween China and Singapore washandled by Chinese junks, and laterthe tongkangs. These vessels werethe chief means of sea transport,The tongkangwas built in sucha manner that itcould lie on riverbeds withouttilting over whenthe tide was out.carrying men and goods betweenSouth China and the Nanyang(South Seas) countries. 1 They alsocalled at ports in Indo-China, Burmaand Thailand. Excluding tradewith Europe, which was carried bysteamships and English lighters, themajor portion of Eastern trade wascarried by tongkangs.Gradually, however, the shippinglanes, mostly European, gainedcontrol of this Eastern tradewith faster and more efficientsteamships. Faced with thiscompetition, junks and tongkangsdeclined in importance but retainedcontrol of the coastal and interislandtrade. Being smaller vessels,they were able to negotiate smallrivers and anchor in shallow waters.In fact, the tongkang was built insuch a manner that it could lie onriver beds without tilting over whenthe tide was out.In the early part of this period, thejunks plying between China andSingapore were owned by tradersin China. As merchants in Singaporeprospered, they acquired their ownvessels built in China. From theinitial role of agents, these tradersbegan to fulfill a new economic roleby providing shipping services.Towards the end of the 19 th century,these merchants began buildingRiverine traffic navigating the mouthof Singapore River at Cavenagh Bridge.their own sailing vessels locally.This was made possible by themigration of Chinese ship-buildersand master craftsmen to Malayawho came with the general flow ofimmigrants. It is difficult to set anexact date when the vessels werebuilt locally and thus determine thebeginning of the tongkang industryproper. Records at the SingaporeRegistry of Ships showed that fromabout 1880 onwards, an increasingnumber of vessels registered werelocally-built sailing vessels. Theywere called “tongkangs” and wereanchored along the Singapore River,especially between Read Bridge andOrd Bridge, forming part of the BoatQuay. The first Chinese boatyardswere therefore situated here orfurther up the Singapore River. 2Most vessels registered in Singaporeby the 1920s were built locally.The building of bridges acrossSingapore River made it impossible,because of their low overhead, fortongkangs and other sailing vesselsto sail up the river. Owners oftongkangs thus were compelled toshift their anchorage to the sea, offBeach <strong>Road</strong> and Crawford Street,which was the major anchoragefor tongkangs until the building ofthe Merdeka Bridge in 1956. TheMerdeka Bridge formed part of animportant arterial road linking theEast Coast areas to the city centreand the Singapore River area. Yetagain, another bridge – MerdekaBridge – then prevented tongkangsfrom sailing up the Rochor andKallang Rivers to discharge theircargoes to warehouses alongCrawford Street and Beach <strong>Road</strong>,and except for timber tongkangs,they shifted again to a shelteredanchorage built by the Singaporegovernment along the GeylangRiver to Tanjong Rhu (known asSandy Point in the earlier part of the19 th century), slightly further east.The Building of TongkangsThe word “tongkang” is Malay,and is probably derived frombelongkang (probably perahubelongkang), a term formerly usedin Sumatra for a river cargo boat(Gibson-Hill, 1952:85-86).Though the tongkang was Chinesebuilt,owned and manned, it wasnot of Chinese origin. Chineseboat-builders adopted the hull ofthe early English sailing lighter,building a hybrid vessel describedas “a fairly large, heavy, barge-likecargo-carrying boat propelled bysail(s), sea-going or used in openharbours. In the immediate area<strong>around</strong> Singapore (Malaya), itsignified a sailing lighter (or barge)with a hull of European origin, or aboat developed from such a stock”(Gibson-Hill, 1952:85-86).There were generally two typesof tongkangs in Singapore– the “Singapore Trader”, a generalpurpose cargo boat used mainlyfor carrying charcoal and fuelwood,with gross tonnage ranging from 50to 150 tons. The second type was the“Timber Tongkang”, used exclusivelyfor carrying saw-logs with grosstonnage of over 150 tons. The hullof both types of tongkangs wasdescribed as a “heavy, unwieldy,wall-sided affair, full in the bilges,with a long straight shallow keel,angled forefoot and heel, a sharpraked bow and a transom stern”(Gibson-Hill, 1952:85-86).The modifications to the tongkangincluded a rectangular rudderpierced with diamond holes,Constructing a tongkanga square gallery projecting overthe stern of the tongkang, and aperforated cut-water.The “Singapore Trader” was 60 – 90feet long with a breadth of 16 – 33feet and a depth of only 8 – 10 feetwhereas “The “Timber Trader” wasmuch larger at 85 – 95 feet in lengthand had a breadth of 30 – 33 feetand a depth of 12 – 15 feet.The small vessels had two masts– the main-mast and the foremast,whereas the large vessels i.e. thoseabove 50 tons stepped three masts;that is, the main-mast, the fore-mastand the mizzen-mast. In the 1950s,the main-sail costed between $250– $300 each, while smaller sailswere priced at $150 – $200 each.Tongkangs were full utility vesselsand about four-fifths of the spaceon a tongkang was used for storingcargo. A small area of deck at thestern of the ship, which was roofed,was used as the crew’s livingquarters in the form of two smallcubicles. The rest of the roofedarea was taken up by the kitchen.A shrine to the goddess Ma-cheh,the guardian of seamen was alwaysaffixed on every vessel.12 13

| FEATURE | | FEATURE |Capital and Recurrent CostsIn the 1950s, a new tongkang below50 tons costed between $10,000 to$15,000 to build while those above100 tons ranged from $70,000 to$80,000. Very few tongkangs werebuilt by about late 1958 because ofthe trade recession which began inearly 1957, and also the decliningimportance of tongkangs as cargocarriers. The few that were builtwere below 50 tons, for service ascharcoal and fuelwood carriers.Tongkangs were overhauled aboutthree times a year, when barnacleswere cleared from the hulls, minorrepairs made and generally aspring-cleaning given, at the costof between $50 to $200 dependingon the size of the ship. Sails werechanged once a year, unless theywere badly torn as a result oftongkangs being lashed by storms.Major repairs were carried out atperiods varying from five to 10years, involving the replacement oftimber of some portions of the ship,changing masts and other costlierrepairs. Properly maintained,tongkangs could last up to 50 years,though most vessels were scrappedafter 30 years of service. Naturallythe rate of maintenance dependedon the volume of trade handledby tongkangs as seen during theKorean War boom, when tongkangswere regularly serviced. Howeverby 1957, overhauling droppedto about twice a year, owing totheir declining importance, andmost were slowly being scrapped,without being replaced.The Tongkang HubThe centre of the tongkang industrywas that part of the island boundby Kallang <strong>Road</strong>, Crawford Street,Beach <strong>Road</strong> and Arab Street whereowners of tongkangs had theirbusiness premises. This centre wasa compact area where seamen couldbe recruited and vessels charteredwithout difficulty.“Timber Tongkangs” anchored andunloaded their cargo of logs intothe sea, off Beach <strong>Road</strong>, the mainanchorage for tongkangs until thebuilding of the Merdeka Bridgein 1956. Logs were towed intothe Kallang Basin, where they laysubmerged in water until requiredby sawmills, resulting in a distinctlyunpleasant smell in the vicinity.All other tongkangs unloaded theircargo of charcoal and fuelwood,poles, planks and sago at TanjongRhu. Though Beach <strong>Road</strong> was thehub of the industry, it was graduallyreplaced by Tanjong Rhu, wherewarehouses and wharves wereconstructed to accommodate thetongkang trade.Tongkangs were used for coastaland inter-island trading, sailing toIndonesia, South Johore, Malacca,Perak and Sarawak. Much of thetrade with Indonesia was mainly inthe Riau and Lingga Archipelagoeswhich lay to the south and southeastof Singapore, the east coast ofcentral Sumatra, namely Siak andIndragiri, and some of the majorislands off the Sumatran coast.Tongkangs in the Kallang Basinnear Malay kampung settlements.Fuelwood cargo carried by tongkangs.The Trade of the TongkangsThe trade handled by tongkangswas part of the larger andextremely important volume oftrade between Singapore andIndonesia, 3 Singapore’s best tradingpartner and valuable customerin the use of entrepôt facilitiesup to the end of 1957, when theIndonesian Government beganto adopt policies to encouragedirect trading with other countries,bypassing Singapore. However,in 1957, imports from Indonesia toSingapore amounted to S$1,099,478945 while exports to Indonesia werevalued at $250,274,272. 4 Indonesiaranked highest in her exports toSingapore which were mainly reexported.The value of Indonesianimports into Singapore was higherthan the combined value of importsfrom the United Kingdom and theUnited States – two major countries.Similar to the faster and moreefficient means of sea-transport,tongkangs also played their partin carrying raw material intoSingapore, to be processed andre-exported, thus adding to thenational income of the island. Themajor items of the tongkang tradewere fuelwood and charcoal, woodin the round, mainly saw-logs andpoles, sawn timber, rubber and rawsago, all non-perishable in naturefor which timing was relativelyunimportant, unlike for foodstuffsand essential raw materials such asrubber. Other produce carried ontongkangs included copra, coffee,tea, and spices. Being slowerthan steamships and freighters,tongkangs were particularly suitedto carry non-perishable cargo morecompetitively than steamships andother faster means of sea-transport.These products were carried toattractive freight earnings fortongkang operators when therewas a shortage of space on thesteamships.Demand, Supply and theImpact on Tongkang CargoesIt is interesting to note that theearnings of the tongkang trade wereaffected by world events and politicssuch as the Korean War in the 1950s,the Suez Canal crisis in 1956 whichimpacted on demand, supply, andprices of goods and freight charges.Local developments such as thehousing shortage, the building ofSingapore Improvement Trust flatsand the shift to use of gas, powerand kerosene as cooking fuelsfrom charcoal and fuelwood alsoaffected the tongkang trade. Bothcharcoal and fuelwood were thenfacing competition from gas, powerand kerosene as cooking fuels.When people of the lower incomegroups, who were important usersof fuelwood and charcoal, occupiedSingapore Improvement Trust flats,they were compelled to use eithergas or power for cooking. Otherhouseholds were also increasinglyswitching to kerosene for cookingpurposes. To meet the challenge,fuelwood and charcoal dealersargued that kerosene, besidesbeing a fire hazard, was unsuitablefor cooking. They claimed that foodcooked over kerosene fire had anunpleasant smell and was not asnutritious as food cooked overcharcoal fire! Though householdswere switching to kerosene, twomajor users of charcoal and fuelwood,namely coffeeshops and restaurants,still used charcoal and firewood, asthey were cheaper than kerosene.Elsewhere overseas, techniquesto turn wheat or maize into starchpowder caused the export of sago tofall – sago being one of the itemscommonly carried by the tongkangs.European manufacturers of starchflour made out of maize, had theadditional advantage of being nearerthe export markets. As a resultdemand for and price of sago fell.Similarly, Singapore sawmillsconsumed less saw log importsfrom Indonesia when overseasdemand for sawn timber, andconsequently their prices, fell.The Demise of the TongkangThe tongkang industry dependedon the demand for the type of cargoa tongkang carried. Unfortunatelythere was a definite falling trend,with the local housing situationat the time and the low volume ofdemand from overseas markets.Besides, the demand for tongkanglabour was a derived demand,being dependent on the volumeof trade handled. The low rate ofnew recruitment into the tongkanglabour force indicated that it wascontracting as men who retiredwere not correspondingly replaced.It was unlikely that tongkangs couldhave switched to carrying othertypes of cargo. Thus the then futureof the tongkang industry was bleak.According to the Annual Report ofthe Registry of Commerce andTongkangs, in dwindling numbers,at their mooring.Industry and the Registry of Ships,Native Sailing Vessels dropped from399 in 1954 to only 299 in 1957.It was obvious that the tongkangtrade was losing out to modernisation,development and shippingtechnologies of the late 1950s and1960s onwards.The eventual decline of the industrywas clearly seen in the increasingnumber of vessels which were beingscrapped annually. As few newvessels were built, the size of thetongkang fleet in Singapore thuscontracted, signalling the gradualdemise of an old practical industryovertaken by modern shipping andport development.Excerpted from “Tongkangs, the Passageof a Hybrid Ship” in Maritime Heritage ofSingapore, pp. 170-181, ISBN 981-05-0348-2,published 2005 by Suntree Media Pte Ltd,Singapore. Call No.: RSING 387.5095957NotesAll statistical data from Statistics Department,Singapore, Annual Imports and Export, I. & E.1Nanyang = southern ocean. Also used byChinese migrants to mean Southeast Asia.2Information from Mr Chia Leong Soon,Secretary of the Singapore Firewoodand Charcoal Dealers’ Association for thisinformation. Read and Ord Bridges are knownto the Chinese as the “fifth” and “sixth” bridgerespectively. A large Chinese boatyard issituated in Kim Seng <strong>Road</strong> along the upperpart of the Singapore River facing the formerGreat World Cabaret (today redeveloped as theGreat World City complex).3Unless otherwise stated, the statisticaldata used in this chapter, were compiledfrom unpublished material in the StatisticsDepartment, Singapore, and cited with thekind permission from the Chief Statistician.4Malayan Statistics: External Trade of Malaya,I & E 3, 1957ReferencesHall, D. G. E. (1955). A History of South-EastAsia, London.Call No.: RSING 959 HALGibson-Hill, C. A. (1952) Tongkang and lightermatters. Journal of the Malayan Branch of theRoyal Asiatic Society, 25(1), 85–86.Call No.: RCLOS v.28 1955 STK 959.5 JMBRASv. 2814 15

| FEATURE | | FEATURE |Beyond Readers and Folktales:Observations about SingaporeChildren’s LiteratureBy Fauziah Hassan, Senior Reference Librarian, Lee Kong Chian Reference <strong>Library</strong> andPanna Kantilal, Senior Librarian, Professional Services<strong>Multi</strong>cultural Children’sLiteratureThe study of multicultural children’sliterature has been makingsignificant inroads into the domainof children’s literature. Howeverwhat constitutes multiculturalliterature? According to Higgins(2002), the term “multicultural” isused to describe “groups of peoplefrom a nonwhite background,people of color, or people of allcultures regardless of race”. In thecontext of this definition, a studyof Singapore children’s literaturewould definitely fall within the realmof multicultural literature.One may ask, why is there a needto study multicultural children’sliterature or Singapore children’sliterature in the first place? HazelRochman (1993) succinctly explainsthat multicultural literature “canhelp to break down [barriers]. Bookscan make a difference in dispellingprejudice and building community”.More importantly, “a good story letsyou know people as individuals inall their particularity and conflict”(Rochman, 1993). For Singapore, anawareness of multicultural children’sliterature would help to throwlight upon the different realitiesin a pluralistic society like ours,where “learning how people fromother cultures do similar things indifferent ways can help childrengain a sense of acceptance andappreciation for diverse cultures”(Hillard, 1995).There are two ways of looking atthis. Firstly, through exposure tomulticultural literature, childrenwould gain a better understandingof themselves as they “identifywith characters that look like them”and they would then be able to“participate in shared culturaltraditions and daily experiences”(Pataray-Ching & Ching, 2001).Secondly, the existence ofmulticultural literature wouldhave an empowering effectas it is written evidence of thecontributions made by those notbelonging to the mainstream whiteculture that is highly prevalent inthe publishing industry.Singapore Children’s LiteratureIn the light of this, Singapore children’sliterature has an important role toplay within the larger context ofchildren’s literature because it wouldideally represent the authentic voiceof the Singapore child. These storiesthat portray Singapore childrenwith their worldview, realities andvalues, would capture the identityof the Singapore child and how theyredefine themselves in the face ofdifferent cultural realities.Our observations of Singaporechildren’s literature has, however,shown that more often than not,these larger issues are sidelinedby the more basic issues suchas authors getting their workspublished in the first place. Manychildren’s authors in Singaporeface the daunting challenge of selfpublishingtheir works becauselocal publishers, due to economicconstraints, often overlook theseworks in favour of more lucrativematerials. This is unfortunate as selfpublishedbooks are sometimes putunder scrutiny and suffer from a lackof credibility.This lack of publisher supporthas existed for a long time. Oneresason for this is the utilitarianattitude towards reading andliterature in Singapore, exacerbatedby the fact that “literature inSingapore is not recognised asa source of vital, vigorous andpossible change-bringing elementsbut as a simple auxiliary of life”(Tay, 1984).Given this, it is not surprisingthat the children’s publishing scenein Singapore has suffered with itschildren’s literature comprisingmainly supplementary readersFor Singapore, an awareness ofmulticultural children’s literature wouldhelp to throw light upon the differentrealities in a pluralistic society likeours, where “learning how peoplefrom other cultures do similar things indifferent ways can help children gain asense of acceptance and appreciationfor diverse cultures.”short stories and folktales, andvery few original works of qualityand merit.A Short History of SingaporeChildren’s LiteratureA rigorous observation of theSingapore children’s literature scenereveals five distinctive categories ofbooks – “the supplementary reader,the picture book, the folktale, themoralizing idyll, and the creativefictional text” (Tay, 1995).The colonial period of the 1950s and1960s saw the blooming of children’sliterature in Singapore authoredby foreigners. One particular bookpublished in Singapore in 1965 isthe Street of the Small Night Marketby British children’s author SylviaSherry. It is an absorbing tale ofAh Ong’s struggle to survive in amenacing Chinatown.All Rights Reserved,Times Books International,1985In the 1970s, literature for childrenwas skewed chiefly towardslanguage acquisition. We couldsay it was the start of the “allfor education” mentality of theparents, many of whom “tend(ed)to measure the worth of readingaccording to its usefulness inschoolwork and in the attainmentof better grades” (Tay, 1995).Literature was not employed as aheuristic mechanism for discoveryand learning but as a didactic meansof language instruction, used toinculcate desirable behaviouraloutcomes. One such book isCourtesy is John’s Way of Life (1979).In Courtesy is John’s Way of Life(1979), the subject matter relatesto the courtesy campaign that ranin the 1970s. The protagonist, Johndisplays courteous behaviour atall times – in school, at home andwith his friends. An unbelievablecharacter indeed – nevertheless,it worked for the campaign.All Rights Reserved,Seamaster Publishers, 1979All Rights Reserved, McGraw-Hill, 1979In The Greedy Boatman (CatherineLim, 1979), we have the moralisingidyll. The folktale, which relatesthe story of a greedy boatmanwho seizes an unfortunate eventto get rich and learns a lessonthe hard way, is another exampleof a book used to encouragegood behaviour.Coming under this category ofdidactic texts are picture bookssuch as Raju and his Bicycle (1978).The simple prose and illustrationswere meant to serve the languageneeds of the reader who was newto English. In addition, popularfolktales such as the Moongateseries by Chia Hearn Chek werewritten to transmit a sense ofhistory and culture to the youngerpopulation. The Raja’s Crown:A Singapore Folktale (1975) is onefine example in the series.All Rights Reserved, EducationalPublications Bureau, 1978Although “useful” reading materialscontinued to be published,children’s books produced in the1980s and 1990s did improve incontent and presentation. Writingtook on a contemporary edge andthe publishing output improvedas more writers and illustrators– both Singaporeans and foreigners– entered the scene. It could be saidthat the 1980s saw the advent ofcreative fictional writing.16 17

| FEATURE | | FEATURE |Illustrations, however, have alwaysbeen a distressing feature of locallyproduced books. For instance, theillustrations in the books discussedabove (Courtesy is John’s Wayof Life and The Greedy Boatman)contain visuals that are dull, staticand unimaginative. Becausethe literary scene for children inSingapore grew more out of aneed for literacy rather than sheercreativity, the illustrations wereuninspired. Bessie Chua’s HolidayTrouble (1990), for example, tracesthe adventures of young Abdul andAini in the kampung days. Writtenfor older children, the book wasaimed at improving their languageproficiency and not to develop anappreciation of art.All Rights Reserved,Landmark Books, 1989All RightsReserved,HeinemannAsia, 1990However it is not all bleak.Remarkable works, such as JessieWee’s Home in the Sky (1989),can be found. In this book, JessieWee tells a heartwarming storyof Ho Seng and his friends whomove into their “home in the sky”– the charming high-rise HousingDevelopment Board (HDB) flats thatare home to many in Singapore. Thestory explores the transition fromsimple kampung living to high-riseliving. While the writing retains aSingapore flavour, the book hasan international appeal with theillustrations showing maturity andan understanding for details.In Poems to Grow Up With (1989)by Patricia Tan, the illustrationsare localised to reflect the localcharacters like the kachang putehman. Tan’s works are suited for arange of readers – adult, youngpeople and children. Some ofpublished stories for childreninclude Spot and I (1982), Raman’sPresent (1983) and Huiming Visitsthe Zoo (1984).All Rights Reserved,Federal Publications, 1989The published materials <strong>around</strong>this time continued to developthe Singaporean flavour of storyand structure. In Kelly Chopard’sMeow: A Singapura Tale (1991), twoSingapura cats, Petta and Larikins,escape from a cat show held atthe Padang, and run into Kuching,a street cat at the SingaporeRiver. Kuching lovingly relatesthe tale of Meow, the great-greatgrandfatherof the Singapura cats,whose heroism saved the life of hisfriend, Ah Kow a labourer. Chopardcontinued writing stories withSingapore’s history and heritage inher two other books – Terry’s RafflesAdventure (1996) and The Tiger’sTale (1987).Into the FutureBeyond the supplementary readers,picture books, folktales, moralistictales and creative texts, what elsedoes Singapore children’s literaturehave to offer? And where does thisleave the reader – child or adult?The Singapore reader, one wouldsay, is left in a vacuum, which thusaccounts for the popularity of theHarry Potter series, the LemonySnicket series, the Hardy Boys andNancy Drew series, and of authorslike Roald Dahl. In all fairness,though, the local Mr Midnight serieshas been extremely popular withSingapore children as has beenmany Singapore ghost stories butthese do not necessarily fall withinthe realm of quality children’sliterature due to their formulaicplots and prosaic writing style.Ironically, Singapore children’sliterature scene is slowly evolving asan increasing number of expatriatewriters enters the local writingscene, such as James Lee, Quirk A,Di Taylor and Joy Cowley.All Rights Reserved,Angsana Books, 2005It is hoped that with a globaloutlook, the publishing scene inSingapore will improve, but giventhe existing climate, children’sauthors, illustrators and publishersThe Singapore reader is left in a vacuum, which thusaccounts for the popularity of the Harry Potter series, theLemony Snicket series, the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drewseries, and of authors like Roald Dahl.in Singapore will have to strive hardfor “the development of a locallyauthored literature… for such aliterature can play a cardinal rolein the perpetuation of indigenouscultural memories and heritages”(Lee, 1990/91). If the issue isignored, Singapore’s society willlose a lot and “unless we createour own internal strength, have asense of our own permanence andidentity, we shall be little more thatan half-way house for the rest of theworld, a clearing house for culturesthat come in and go out from us”(Lee, 1990/91). That permanence andidentity can be created when wehave our own Singapore children’sliterature which children here canidentify with and be proud of.As Patary-Ching and Ching(2001) pointed out, we need“a multicultural library of children’sbooks” which acts as “an enablingmuseum of living culture throughwhich children may travel andremember”.The Lee Kong Chian Reference <strong>Library</strong>’s AsianChildren’s Collection is a unique collectionof 20,000 children’s titles. This collection isa gem as it comprises an extensive array ofSingapore children’s literature. At the sametime, it collects Asian children’s literaturespanning the Asian region and beyond,including works on Asian diaspora.ReferencesChua, Bessie. (1990). Holiday trouble. Singapore: Heinemann Asia.Call No.: RAC 428.6 CHUCourtesy is John’s way of life. (1979). Singapore: Seamaster Publishers.Call No.: RAC 428.6SEAHiggins, J.J. (2002). <strong>Multi</strong>cultural children’s literature: Creating and applying an evaluation tool inresponse to the needs of urban educator.http://www.newhorizons.org/strategies/multicultural/Higgins.htmHillard, L.L. (1995). Defining the multi- in multicultural through children’s literature. The ReadingTeacher, 48, (8), 728.Lee, J. (2004). Mr Mididnight: Madman’s mansion and the monster in Mahima’s mirror. Singapore:Angsana Books.Call No.: RAC S823 LEELee, T.P. (1990/91). Keynote address. Singapore Book World (special issue), 20, 8-17.Lim, C. (1979). The greedy boatman. Singapore: McGraw-Hill.Call No.: RAC 428.6 LIMPataray-Ching, J., & Ching, S. (2001). Talking about book: Supporting and questioning representation.Language Arts, 78 (5), 476-484.Raju and his bicycle. (1978). Singapore: Educational Publications Bureau.Call No.: RAC 428.6 RAJRochman, H. (1993). Against borders: Promoting books for a multicultural world. Chicago,IL: American <strong>Library</strong> Association.Call No.: R 011.62 ROC -[LIB]Tan, P.M. (1989). Poems to grow up with. Singapore: Federal Publications.Call No.: RAC S821 TANTay, M.L. (1995). Singapore revisited: A study of landscapes through children’s literature. Singapore.Call No.: R SING 809.89282 TAYTay, S. (1984). The writer as a person. Solidarity, 99, 56-59.Wee, J. (1989). A home in the sky. Singapore : Landmark Books.Call No.: RAC 428.6 WEE18 19

| FEATURE | | FEATURE |Sebuah Mercu Tanda IlmuBy Juffri Supa’at, Reference Librarian, Lee Kong Chian Reference <strong>Library</strong>Pembinaan tamadun ilmu hanya mungkin terhasil jika ilmu diberikan statussebagai “the highest good” (kebaikan mutlak) atau menduduki martabattertinggi dalam sistem nilai individu dan masyarakat.ms 45, Budaya Ilmu, Satu PenjelasanWan Mohd Nor Wan DaudPerpustakaan Negara yang baruini telah dibina sebagai sebuahperpustakaan yang moden danunik bagi menghadapi cabaran dankeperluan generasi masa kini di dalammengharungi dunia berteraskan ilmu.Bangunan gah setinggi 16 tingkatyang terletak di Victoria Street inidipenuhi dengan koleksi sebanyak634,000 bahan. Ia juga menyediakanperkhidmatan dan kemudahanyang menyeluruh sesuai denganvisinya menjadi sebuah pusat ilmu.Dengan ruang seluas 58,000 meterpersegi, bangunan ini lima kali lebihbesar jika dibandingkan denganbangunan lama di Stamford <strong>Road</strong>.Ia juga menempatkan PerpustakaanPinjaman Central yang terletak diBasement 1.Antara yang menjadi tumpuan utamabangunan ini ialah PerpustakaanRujukan Lee Kong Chian, NamaLee Kong Chian diabadikansempena memperingati semangatkedermawanan Dr Lee Kong Chian,pengasas Yayasan Lee yang telahmemberi sumbangan sebanyak $60juta kepada perpustakaan baru ini.Perpustakaan Rujukan Lee KongChian yang memenuhi tingkat 7ke tingkat 13 mempunyai koleksimelebihi 500,000 bahan di dalampelbagai bidang dan format. Iabersesuaian dengan tekadnya untukmenjadi sebuah pusat sumbermaklumat utama bagi kajian danrujukan terutama sekali yangberkaitan dengan Singapura danAsia Tenggara untuk memenuhikeperluan informasi golonganpengkaji, karyawan dan juga parapengguna am.Koleksi-koleksi di Perpustakaan ini disusun berdasarkan bidang-bidangberikut:Tingkat 7Tingkat 8Tingkat 9Tingkat 10Tingkat 11Tingkat 13Koleksi Sains Sosial dan KemasyarakatanKoleksi Sains dan TeknologiKoleksi Seni dan PerniagaanKoleksi Cina, Melayu dan TamilKoleksi Kanak-kanak AsiaKoleksi PendermaKoleksi Singapura and Asia TenggaraKoleksi Bahan-bahan NadirKoleksi Cina, Melayu dan Tamil(Tingkat 9)Koleksi-koleksi ini dibangunkanbagi memartabatkan perananPerpustakaan Rujukan Lee KongChian sebagai sebuah pusat rujukandan penyelidikan yang cemerlangdengan memenuhi keperluan rakyatSingapura mencari dan mengaksesmaklumat di dalam bahasaCina, Melayu dan Tamil. Ia kinimempunyai sebanyak 67,200 bahan.Koleksi-koleksi ini mengetengahkanbudaya dan nilai tradisional yangmencerminkan aspek-aspeksosio-ekonomi, kebudayaan dankesusasteraan ketiga-tiga kumpulanetnik di Singapura.Koleksi MelayuKoleksi Melayu menyentuh segalaaspek kehidupan masyarakatdi Kepulauan Melayu, termasuksosio-ekonomi, politik, kebudayaan,agama, bahasa, kesusasteraan danpembangunan negara. Bahan-bahanKoleksi Rujukan Melayu Am inimembentuk bahagian yang besar diHak CiptaTerpelihara,Balai Pustaka,1953Sebuah kumpulan naskhah-naskhahdrama karya Armijn Pane, salahseorang sasterawan IndonesiaAngkatan Pujangga baru.antara keseluruhan Koleksi MelayuPerpustakaan Rujukan Lee KongChian. Koleksi ini mengandungimonograf, terbitan berkala, bahanbahanpandang-dengar danmikrofilem. Juga terdapat bahanbahankhusus untuk rujukan sepertikamus, ensiklopedia, direktori,biografi, bibliografi, buku tahunan,peta, indeks dan abstrak.Antara yang menarik yang bolehdidapati di dalam koleksi ini ialahkoleksi berkenaan kesusasteraan,bahasa dan Islam.Koleksi Kesusasteraan merangkumikedua-dua sastera Melayu tradisional/klasik dan moden. Koleksi inidiperkayakan dengan bahan-bahanyang menyentuh tentang teori danfalsafah kesusasteraan, puisi, drama,novel, esei dan kritikan kesusasteraanoleh penulis-penulis dari BruneiDarussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia,Filipina, Singapura dan Thailand.Hak CiptaTerpelihara,UniversitiKebangsaanMalaysiaBangi, 2001Buku ini mengungkapkan isu-isusekitar pemikiran alam melayu olehtokoh-tokoh sarjana yang mencabar danmenduga keutuhan tamadun Melayu.Koleksi Bahasa terdiri daripada bahanbahantentang bahasa Melayu danperkembangannya. Bahasa Melayumerupakan bahasa perantaraan diKepulauan Melayu pada suatu ketikadahulu. Ia juga adalah bahasa yangutama dan memainkan perananpenting sewaktu pengislamanSemenanjung Melayu. Bagi menghargaiperanan yang dimainkan oleh bahasaMelayu dalam masyarakat,Perpustakaan Rujukan Lee Kong Chiancuba mengabadikan intipati bahasaini dari berbagai aspek, termasukfalsafah dan teori, fonologi dan nahu.Koleksi Islam tertumpu pada bahanbahanberkaitan dengan ketamadunanHak CiptaTerpelihara,Akbar MediaEka Sarana,2003Buku yang membicarakan tentangsejarah Islam sejak dari zamanNabi Adam a.s. hingga kini. Ia jugamembincangkan isu-isu orang Islamyang menjadi kumpulan minoriti dinegara-negara bukan Islam.Islam seperti nilai-nilai, amalanamalanserta cara kehidupan dalamIslam. Penekanan khas diberikankepada sumber-sumber berhubungIslam di Kepulauan Melayu.Koleksi Asia Kanak-kanakKoleksi Asia Kanak-kanakmengandungi bahan-bahan yangditulis khas untuk kanak-kanakberkaitan dengan negara-negaraAsia dan penduduknya. Koleksiini merangkumi buku kanak-kanakdalam ke empat-empat bahasarasmi Singapura dan merupakansumber yang paling sesuai bagipara pendidik, pelukis ilustrasidan sesiapa sahaja yang berminatdalam penggunaan dan penghasilanbahan-bahan bacaan dan tulisan untukkanak-kanak dari perspektif Asia.Koleksi Singapura danAsia TenggaraKoleksi-koleksi ini adalah sumberbahan penyelidikan sejarah yangbernilai. Keistimewaan koleksikoleksiini ialah karya-karyaberkaitan sejarah, pemerintahan,budaya dan adat, bahasa dansastera. Para penyelidik juga bolehmerujuk kepada 24,000 unit bahanmikrofom, terdiri daripada bahanbahanterbitan sebelum tahun1900, akhbar-akhbar tempatan danmajalah-majalah berkala keluaranlampau serta tesis-tesis. Terdapatjuga peta meliputi Singapura,Malaysia dan negara-negara AsiaTenggara yang lain, serta posterpostertentang Singapura dalamkoleksi ini. Tambahan lagi, 15,000unit bahan pandang-dengar sepertivideo, cakera padat, cakera laser,VCD dan DVD ditempatkan disini. Sebahagian daripada bahanbercetak telah ditukarkan formatnyakepada bentuk digital dan kinitersedia untuk penggunaan ramaidi Perpustakaan Digital kami.Sumber-sumber SingapuraDi antara tumpuan koleksi dibahagian ini ialah bahan-bahansumber Singapura dan juga AsiaTenggara. Ia terdiri dari bahan-bahan berkaitan Singapura danpenduduknya yang komprehensifdalam semua format, termasuksumber-sumber asas dan yang telahditerbitkan dalam berbagai disiplin.Ia juga merangkumi karya-karyaberkaitan Negeri-Negeri Selat danMalaya di mana Singapura pernahmenjadi sebahagian daripada entitipolitiknya.Di samping itu, terdapat juga bahanbahanyang mendokumenkan liputanpenting tentang Malaysia, Indonesia,Brunei, Thailand, Kampuchea,Filipina, Timor Timor, Laos, Vietnamdan Myanmar, terutama dalambidang-bidang sejarah, politik danpemerintah, budaya dan adat, floradan fauna serta ekonomi.Koleksi Bahan-bahan NadirSebahagian besar koleksi inimengandungi bahan-bahan yangdicetak pada abad ke sembilanbelas dan awal abad ke dua puluh.Kebanyakan daripada bahanbahanini diterbitkan oleh syarikatsyarikatpercetakan akhbar yangterawal di Singapura. Koleksi inijuga mengandungi manuskripMelayu bertulisan Jawi, kamusdalam bahasa Melayu dan bahasabahasaAsia Tenggara, direktori danalmanak, jurnal ilmiah, kisah-kisahpengembaraan di kepulauan Melayudan Asia Tenggara, serta terbitanCina klasik yang diceritakan semuladalam bahasa Melayu Baba.Untuk pertanyaan mengenaiPerpustakaan, sila hubungi:Perpustakaan Rujukan Lee Kong Chian100 Victoria Street #07-01Singapura 188064Tel: +65 6332 3255Fax: +65 6332 3248Laman Web: www.nlb.gov.sgWaktu pembukaan:Isnin – Ahad(ditutup pada Cuti Umum)10 pagi – 9 mlmUntuk perkhidmatan rujukan,sila hubungi:Emel: ref@nlb.gov.sgSMS: +65 9178 7792Fax: +65 6332 324820 21

| FEATURE | | FEATURE |Fostering an Inventive Spiritin the City-StateBy Sara Pek, Senior Reference Librarian, Lee Kong Chian Reference <strong>Library</strong>Invention and InnovationAccording to Fagerberg, Mowery andNelson (2005), there is a distinctionbetween invention and innovation:“Invention is the first occurrenceof an idea for a new product orprocess, while innovation is the firstattempt to carry it out into practice...In many cases, however there isa considerable time lag betweenthe two. While inventions may becarried out anywhere, for examplein universities, innovations occurmostly in firms… To be able to turnan invention into an innovation, afirm normally needs to combineseveral different types of knowledge,capabilities, skills and resources.”An example of an inventiveperson is Leonardo da Vinci.He embodies the very spirit ofinvention. Leonardo lived inthe Renaissance Period (1400– 1600 CE) where a time of greatcultural advances and explosionof knowledge dissemination werebrought on by printing techniques.This self-taught man researchedand formulated ideas and plansin a multitude of disciplines thatranged over anatomy, botany,science and technology, and thevisual arts. The unique record of“word and image” from his detailedmanuscripts allows us a glimpseinto his incredible mind. Mostsignificantly, it expresses what menand women of the time felt andthought about the machines andtools and used for greater purposessuch as constructing churches,palaces and machines for warfareand transportation. (Farago, 1999)Vision, Motivation and NecessityMore often than not, invention stemsfrom vision. In 1819, Sir StamfordRaffles saw the unrealised potentialin a small fishing village andSingapore was founded as a Britishtrading post on the Straits ofMalacca. From then on, Singaporegrew from a colonial outpost into theworld’s busiest port (Drysdale, 1984;Turnbull, 1989; Chew & Lee, 1991).Vision is followed by motivation,which encourages invention. Theearly Singapore settlers wereinventive in their thinking – theyendured hardship to build theirlives in a foreign land as they sawopportunities for economic andsocial advancement.Necessity breeds invention, bringingideas to fruition. Early settlerswere forced to build roads andtowns to thrive in the harshenvironment. During the SevereAcute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)outbreak, ST Electronics and theDefence Science and TechnologyAgency (DSTA) adapted a thermalscanner originally meant for militaryuse. It was used at the airport,immigration checkpoints, ministriesand hospitals to scan large groupsof people simultaneously forhigh temperature and proved animportant tool in the managementA walk-through thermal scanneroriginally meant for military use.Image courtesy of SingaporeTechnologies Electronics LimitedGrowing Venturesof SARS. The system was namedby TIME magazine as one ofthe coolest inventions in 2003(Channelnewsasia, 11 Nov 2003).Singapore has greatly benefitedfrom knowledge and technologicaltransfers from multinationalcorporations and foreign talentfrom developed countries. Inadvancing towards a knowledgebasedeconomy, the ongoingcreation of ideas and inventions byinstitutions and people is crucial.This is recognised by the Singaporegovernment, which invests heavilyin research and development,and has expanded its initiativesin developing Singapore into aregional Intellectual Property Hub(Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2006).Schools also attempt to cultivatedesired attributes and mindsetssuch as intellectual curiosity, selfreliance,ruggedness, creativity andcommunity spirit. The Tan Kah KeeYoung Inventors’ Award, which hasbeen in existence since 1986, hassparked imaginations among studentsand stimulated them to invent things.Tertiary education in science andtechnology fields at university andpolytechnic levels is strengthened withthe encouragement of research andknowledge creation.A wide range of support initiativesis offered to individuals eager todevelop functional prototypes orstart up new ventures. Among themare: Venture Investment Supportfor Start-ups (VISS), The StartupEnterprise Development Scheme(SEEDS), Technopreneur InvestmentIncentive Scheme (TII), The EnterpriseChallenge Scheme (TEC), GlobalStartup @ Singapore Business PlanCompetition, Hub of TechnopreneursSpots (HOT Spots), SingaporeInnovation Award (I-Award) andGlobal Entrepolis@Singapore.Over the past decade, Singapore’sintellectual assets have grownsignificantly. Patent applicationsincreased sharply from 1,818 in 1994to 8,000 in 2003 (Straits Times, 18Nov 2004). The 2004 annual R&Dsurvey conducted by Agency forScience, Technology and Research(A*STAR) reported that the“numbers of patent applicationsand awards increased by 26% and30% respectively from 1,001 and 460in 2003 to 1,257 and 599 in 2004”.In the same year, A*STAR filedover 120 patents worldwide (StraitsTimes, 29 Jul 2005).It is often said that Singaporeansare risk averse and lack creativity.A prevailing culture of failureintolerancemay have quelled manya desire to experiment and makechanges. To add economic value to anew or improved product or service,one needs to risk resources (natural,human and capital) to bring it to themarket. Vandenborre (2003) claims“we are still at a very early stage ofentrepreneurship compared to theUnited States. At the same time,because we lack the critical marketsize, we have to think globallyalmost instantaneously. What weneed is to develop a more efficientcapital market infrastructure forsmaller companies”. He believes thatentrepreneurship is a mindset thatcould be “nurtured and developed”by reaching out to students inschools and tertiary institutions,and by organising entrepreneurshipprogrammes for the adult workforce.Through the early years ofindustralisation, the city-state hastransformed itself into a thrivingknowledge economy, supportedby strong intellectual propertylaws, an educated workforce,quality research and developmentinstitutions, and low barriers totrade and foreign investments. Thereis a real sense of survival throughinnovation for both economic andsecurity reasons.A host of activities will be held at the <strong>National</strong><strong>Library</strong> in August. Organised in collaborationwith the Economic Development Board andits partners, the events comprise exhibitions,information sharing and talks on hot topics byhomegrown inventors. The meetings will allowinventors to find out more about the supportand guidance that is available to them, pick uptips and meet other inventors in an informalenvironment.Resources for InventorsThere are hundreds of books, reference and online resources to help buddinginventors better understand the invention and innovation process – idea generation,problem solving to business 101, general marketing to safeguarding intellectualproperty through patents and trademark. Here are some of the resources:BooksA Complete Idiot’s Guide to Cashing in on Your Inventions by Richard LevyPublisher: Indianapolis, Ind.: Alpha Books, 2002 Call No.: R 346.73048 LEVLevy shares his experiences in bringing his many products to market successfully. He offerstips on how to profit from one’s invention and gives advice on how to avoid pitfalls, securepatent protection and licensing, develop prototypes and negotiate deals and contracts.A Guide to Protecting Your Ideas, Inventions, Trade Marks & Products by Catherine TayPublisher: Singapore: Times Editions/Marshall Cavendish, 2004 Call No.: RSING346.5957048 TAYThis publication explains the “do’s” and “don’ts” and provides essential information onprotecting ideas and inventions while helping one navigate the labyrinth of concepts,rules and laws in Singapore.The 3M way to Innovation: Balancing People and Profit by Ernest GundlingPublisher: Tokyo: Kodansha International, c2000 Call No.: RBUS 658.4063 GUN3M has always been held up as the role model of an innovative organisation. This bookprovides invaluable insights into the principles and best practices that have kept 3M onthe cutting edge.DatabasesIndustry-specific journals as well as market intelligence are useful to gauge the market potential ofyour inventions. These are accessible from online databases at all multimedia stations in the <strong>Library</strong>:EbscoHost Business Source Premier provides full text business journals and publications in theareas of management, taxation, marketing, sales, economics and finance.Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) provides analyses of political and economic trends and a historical contextof current events in nearly 200 countries. Includes a fortnightly business brief on doing business in Asia.Euromonitor’s Global Market Information Database (GMID) offers key business intelligence oncountries, companies, markets and consumers.Factiva allows access to a deep archive of news and business information.Engineering Information Village (Ei Village) is a virtual community for engineers, created to provideinformation needed to solve problems and keep up to date with trends and developments in thefield of engineering. Includes access to databases, websites and libraries.InternetThe US Patent & Trademark Office and Patent & Trademark Depository <strong>Library</strong> Associationare websites devoted to resources to help inventors.http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/com/iip/; http://www.ptdla.org/resources/assistance.htmlThe Lemelson-MIT Invention Dimension website provides a wealth of inventor resources including patentguidelines and links to many online invention resources. http://web.mit.edu/invent/invent-main.htmlLicense Finder allows one to search for the latest information on licenses granted and availablelicensers. It also features articles about licensing opportunities and trade shows.http://finder.licensemag.comEnterpreneur has many useful articles on getting started, inventors’ success stories, smart ideas and more.http://entrepreneur.comReferencesAgency for Science, Technology and Research. (2004). Annual R&D survey. Retrieved 9 May fromhttp://www.a-star.edu.sg/astar/front/media/content_uploads/Booklet_2004.pdfBig patent player sets up shop in Biopolis. (18 November 2004). Straits Times.Boey, D. (10 September 2004). US award for team behind fever scanner. Straits Times.Chew, Ernest C.T. & Lee, E. (Eds.). (1991). A history of Singapore. Singapore : Oxford University Press.Drysdale, J. (1984). Singapore, struggle for success. Singapore: Times Books International.Farago, C. (Ed.). (1999). Leonardo’s science and technology: Essential readings for the non-scientist.New York; London: Garland Pub.Fagerberg, M., David C. & Nelson, R. R. (Eds.). (2005). The Oxford handbook of innovation. Oxford;New York: Oxford University Press.Khushwant, Singh. (29 July 2005). Book on local patent law launched. Straits Times.Ministry of Trade and Industry. (2006). Science & technology plan 2010: Sustaining innovation-drivengrowth. Singapore: Ministry of Trade and Industry.Saywell,T. (22 January 2004). 4th Young Inventors Awards: Winners: Bronze. Far Eastern Economic.Review. Retrieved 9 May from http://www.feer.com/articles/2004/0401_22/free/p040innov.htmlThermal scanners named as one of this year’s coolest inventions. (11 November 2003. 21:30). Channelnewsasia .Turnbull, C.M. (1989). A history of Singapore, 1819-1988. Singapore: Oxford University Press.Vandenborre, A. (2003). Proudly Singaporean: My passport to a challenging future. Singapore: SNP Editions.22 23

| FEATURE | | FEATURE |Marching Through the Decades: Singaporeon Parade, an Online ExhibitionBy Nor-Afidah Abd Rahman, Senior Reference Librarian, Lee Kong Chian Reference <strong>Library</strong>Parades for All Seasons…The ceremonies you have seen today are ancient, and some of their originsare veiled in the mists of the past. But their spirit and their meaning shinethrough the ages never, perhaps, more brightly than now...Queen Elizabeth II. Excerpt from broadcast made on the evening of theQueen’s Coronation, 2 June 1953.Source: British Monarchy. (n.d.). The Queen’s speeches. Retrieved May 10,2006, from www.royalinsight.gov.ukSingapore is as old as the historyof the settlement. The founding ofSingapore on February 1819 wasushered in with a parade. Indiansepoys and European artillerymenwere among the first to stamp theirfeet on the Plain (now the Padang)in cohesion, while offshore theguns from the ships roared whenthe Union flag was hoisted up.Pomp and gallantry certainly didnot escape this historic ceremony.A hundred years later, anotherparade and other festivities tookplace in Singapore to mark the100 th anniversary of the colony’sfounding. The colony had survivedand thrived, a milestone worthy ofa Centenary Day celebrations. OnEmpire Day at Raffles Institutionin 1947. Image from the RafflesInstitution collection, <strong>National</strong>Archives of Singapore.Coronation day decorations inSingapore for King Edward VII andQueen Alexander. Image courtesyof <strong>National</strong> Archives of Singapore.Most people love parades for theyare festive and escapist; day-to-daytasks take a standstill as peoplecongregate at common venues totreat themselves to a spectacle ofprecision, colours loud music andfireworks. Parades are timelesssymbols of unity as they transcend<strong>ethnic</strong>ity and age, and showcaseicons of progress that everyone canidentify and be proud of.On 9 August every year,Singaporeans look forward tothe <strong>National</strong> Day Parade (NDP)to celebrate their independence.Military drills, band performances,fly- and march-pasts and fireworksnever fail to excite us. As Singaporeprepares for her 41 st NDP on9 August 2006, we reminisce thecountry’s commitment to thispageantry to commemorate theoccasion through the Singaporeon Parade online exhibition. Thisexhibition aims to recapture the finemoments and grandeur of the grandparades in Singapore from colonialto modern times. The ceremoniesin pre-independence parades wereof British conception and carriedmessages of British empirebuilding.But traditions die hardand many of the parade rituals seenthen have continued into presentday NDPs. The main difference liesin the spirit and meaning; whilepre-independence parades rejoicedat Singapore’s patronage to thegreatest empire on earth, NDPscelebrate Singapore’s triumph as anation united by the country’s owndefined ideals of progress.Parades of YesteryearPerhaps it is not widely knownthat the history of parades in1819: The Treatyand the Parade1919: Centenary Day Celebrations.Reproduced from Song‘s OneHundred Years’ History of theChinese in Singapore (p. 297).All Rights Reserved, OxfordUniversity Press, 19846 February 1919, the Centenarykicked off with a parade at theVictoria Theatre and MemorialHall and the unveiling of acommemoration tablet on the newlyrelocated Raffles Statue. The statuewas moved from the Padang to theMemorial Hall for this occasion.Colonial parades burst into thestreets in kaleidoscopic scale duringQueen Victoria’s reign (1837 – 1901).She ruled the longest and wasthe most celebrated sovereign inSingapore though her successorswere no less prominent. FromQueen Victoria to Queen ElizabethII, Singapore paid homage to herBritish sovereigns through countlessparades; birthday parades, EmpireDay parades, coronation parades,and Golden, Diamond and Silverjubilee parades.From the late 19 th century, thecelebration of British royal events(coronation, birthday and jubilees)had spilled over from London tothe various colonies. As sharedoccasions across the Empire, theseMass Display during NDPImage courtesy of MINDEF.events were celebrated with acommon style, involving bannersand flags, speeches and streetparties, military processions, theunveiling of statues or the openingof memorial halls. Not to beoutdone, Singapore’s version of thecelebrations had enough buntingsand illuminations to turn the wholetown into a magical fairyland. Thenewspaper became an importanttool to announce the variousprogrammes scheduled for thecelebrations. Each <strong>ethnic</strong> group hadtheir own way to show support tothe sovereign on these occasions;the Arabs decorated an arch theyconstructed with “God Save TheKing” neon lights; the Jews heldspecial prayers at the synagogue;the Chinese, Malays and Indianscombined to organise a procession,even the Japanese communitycontributed firework displays.People’s Parade: A FlawlessSymphonyOver the decades, parades havebecome distinctly Singaporean.Modern day NDPs have evolved into“people’s parade” where everybodyparticipates. From the mass displaysand fireworks to the reciting of the<strong>National</strong> Pledge and singing of the<strong>National</strong> Anthem, everyone has arole to play. This hearty mobilisationNDP 1991Image courtesy of MINDEF.24 25