searchable PDF - Association for Mexican Cave Studies

searchable PDF - Association for Mexican Cave Studies searchable PDF - Association for Mexican Cave Studies

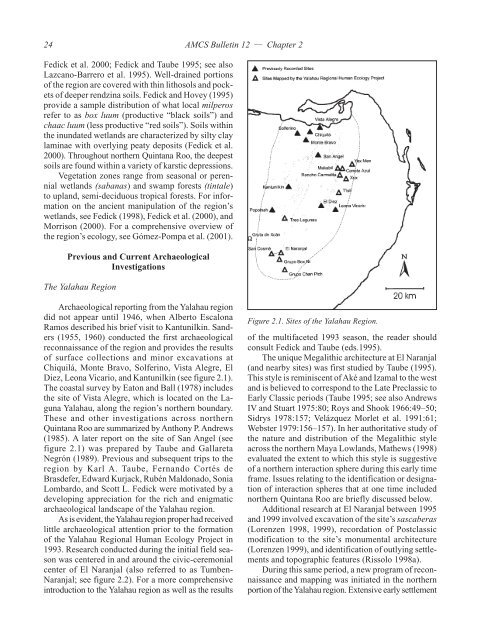

24AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 2Fedick et al. 2000; Fedick and Taube 1995; see alsoLazcano-Barrero et al. 1995). Well-drained portionsof the region are covered with thin lithosols and pocketsof deeper rendzina soils. Fedick and Hovey (1995)provide a sample distribution of what local milperosrefer to as box luum (productive “black soils”) andchaac luum (less productive “red soils”). Soils withinthe inundated wetlands are characterized by silty claylaminae with overlying peaty deposits (Fedick et al.2000). Throughout northern Quintana Roo, the deepestsoils are found within a variety of karstic depressions.Vegetation zones range from seasonal or perennialwetlands (sabanas) and swamp forests (tintale)to upland, semi-deciduous tropical forests. For informationon the ancient manipulation of the region’swetlands, see Fedick (1998), Fedick et al. (2000), andMorrison (2000). For a comprehensive overview ofthe region’s ecology, see Gómez-Pompa et al. (2001).Previous and Current ArchaeologicalInvestigationsThe Yalahau RegionArchaeological reporting from the Yalahau regiondid not appear until 1946, when Alberto EscalonaRamos described his brief visit to Kantunilkin. Sanders(1955, 1960) conducted the first archaeologicalreconnaissance of the region and provides the resultsof surface collections and minor excavations atChiquilá, Monte Bravo, Solferino, Vista Alegre, ElDiez, Leona Vicario, and Kantunilkin (see figure 2.1).The coastal survey by Eaton and Ball (1978) includesthe site of Vista Alegre, which is located on the LagunaYalahau, along the region’s northern boundary.These and other investigations across northernQuintana Roo are summarized by Anthony P. Andrews(1985). A later report on the site of San Angel (seefigure 2.1) was prepared by Taube and GallaretaNegrón (1989). Previous and subsequent trips to theregion by Karl A. Taube, Fernando Cortés deBrasdefer, Edward Kurjack, Rubén Maldonado, SoniaLombardo, and Scott L. Fedick were motivated by adeveloping appreciation for the rich and enigmaticarchaeological landscape of the Yalahau region.As is evident, the Yalahau region proper had receivedlittle archaeological attention prior to the formationof the Yalahau Regional Human Ecology Project in1993. Research conducted during the initial field seasonwas centered in and around the civic-ceremonialcenter of El Naranjal (also referred to as Tumben-Naranjal; see figure 2.2). For a more comprehensiveintroduction to the Yalahau region as well as the resultsFigure 2.1. Sites of the Yalahau Region.of the multifaceted 1993 season, the reader shouldconsult Fedick and Taube (eds.1995).The unique Megalithic architecture at El Naranjal(and nearby sites) was first studied by Taube (1995).This style is reminiscent of Aké and Izamal to the westand is believed to correspond to the Late Preclassic toEarly Classic periods (Taube 1995; see also AndrewsIV and Stuart 1975:80; Roys and Shook 1966:49–50;Sidrys 1978:157; Velázquez Morlet et al. 1991:61;Webster 1979:156–157). In her authoritative study ofthe nature and distribution of the Megalithic styleacross the northern Maya Lowlands, Mathews (1998)evaluated the extent to which this style is suggestiveof a northern interaction sphere during this early timeframe. Issues relating to the identification or designationof interaction spheres that at one time includednorthern Quintana Roo are briefly discussed below.Additional research at El Naranjal between 1995and 1999 involved excavation of the site’s sascaberas(Lorenzen 1998, 1999), recordation of Postclassicmodification to the site’s monumental architecture(Lorenzen 1999), and identification of outlying settlementsand topographic features (Rissolo 1998a).During this same period, a new program of reconnaissanceand mapping was initiated in the northernportion of the Yalahau region. Extensive early settlement

AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 2 25and evidence of wetland manipulation was identifiedwithin the Reserva Ecológica El Edén and gave riseto a number of related research projects (see Fedicket al. 2000 for an overview; see also Andersen 2001;Fedick, ed. 1998; Morrison 2000). Recently, focus hasshifted to the site of T’isil, which is located just southof El Edén reserve. As work progresses, new insightsinto the region’s early settlement history emerge(Amador 2001; Ceja-Acosta 2001; Ceja-Acosta andRissolo 2001; Fedick and Mathews 2001; Glover andAmador 2001; Mooney-Digrius 2001; Morell-Hart2001). Future research in the northern Yalahau regionwill include continued studies of community organizationat T’isil, an extensive settlement survey by JeffreyGlover and Fabio Esteban Amador, continuedanalysis of regional ceramics by Jorge Ceja Acosta,and further investigation of the purported transregionalsacbe by Jennifer Mathews (see Mathews1998, 2001).Figure 2.2. Map of El Naranjal (after Fedick and Taube1995:fig. 1.8).Research at the Region’s PeripheryThe nearest major civic-ceremonial center is Cobá,which is located approximately 35 km from the southernterminus of the Yalahau region (see map in figure1.1). Early work at the site was reported by Thompsonet al. (1932). For the results of subsequent researchprojects see Con (2000), Con and Martínez Muriel(1992), Folan et al. (1983), González Fernández(1975), Manzanilla (1987), and Robles Castellanos(1990). Robles Castellanos and Andrews (1986) suggestthat Cobá was the dominant polity of an easternsphere during the Terminal Classic. Mathews (1998)argues convincingly that sphere affiliations may havediffered greatly in northern Quintana Roo during theLate Preclassic to Early Classic periods. I would stressthat many of the questions concerning sphere designationand political organization during this earlyphase are “ceramics questions.” Mathews’ researchprovides a foundation from which formal, problemorientedanalyses of regional pottery can progress. Itshould be noted that the Middle Preclassic materialrecovered from the caves of the Yalahau region (anddescribed in Chapter 5 of the dissertation) provides apreliminary look into the region just beyond the Cobáperiphery, at a time before the emergence of this powerfulcenter.To the north of Cobá is the smaller site of PuntaLaguna (see Cortés de Brasdefer 1988) and to thenortheast is the major center of Ek Balam. MiddlePreclassic material was also recovered at Ek Balam(Bey et al. 1998) and the site was likely an importantpower during the area’s early settlement. North of EkBalam is a region defined by the Contact Period provinceof Chikinchel. This area, which borders thewestern edge of the Yalahau region, has been extensivelystudied by Susan Kepecs (1997, 1998; see alsoKepecs and Boucher 1996; Kepecs and GallaretaNegrón 1995). A consideration of the ceramics fromChikinchel is included in Chapter 5 of the dissertation.Few studies of the northernmost Caribbean coast(to the east of the Yalahau region) have been produced.Andrews and Robles (1985) describe excavations atthe site of El Meco and a description of the Ecab provinceis provided by Benavides Castillo and Andrews(1979). The sites of Cancún (to the south) were firstreported in detail by Lothrop (1924) and later researchon the island was conducted by Andrews IV et al.(1974). A review of the archaeological literature regardingthe Caribbean coast south of Cancún—as itpertains to coastal cave sites—is presented in the followingchapter.

- Page 3 and 4: ANCIENT MAYA CAVE USEIN THE YALAHAU

- Page 5 and 6: ANCIENT MAYA CAVE USEIN THE YALAHAU

- Page 7 and 8: AMCS Bulletin 12 5CONTENTSList of F

- Page 9 and 10: AMCS Bulletin 12 7FIGURES CONTINUED

- Page 11 and 12: AMCS Bulletin 12 9FIGURES CONTINUED

- Page 13 and 14: AMCS Bulletin 12 11FOREWORDIt is a

- Page 15 and 16: AMCS Bulletin 12 13easily said that

- Page 17: AMCS Bulletin 12 15ABSTRACTFor the

- Page 20 and 21: 18AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 1Fig

- Page 22 and 23: 20AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 1str

- Page 25: AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 2 23CH

- Page 30 and 31: 28AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 3but

- Page 32 and 33: 30AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 3Cav

- Page 34 and 35: 32AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 3Fig

- Page 36 and 37: 34AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 3see

- Page 38 and 39: 36AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 3elu

- Page 40 and 41: 38AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4whi

- Page 42 and 43: 40AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4is

- Page 44 and 45: 42AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4of

- Page 46 and 47: 44AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4Tab

- Page 48 and 49: 46AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4the

- Page 50 and 51: 48AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4Tab

- Page 52 and 53: 50AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4Abo

- Page 54 and 55: 52AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4Tab

- Page 56 and 57: 54AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4Clo

- Page 58 and 59: 56AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4Lot

- Page 60 and 61: 58AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4Tab

- Page 62 and 63: 60AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4rou

- Page 64 and 65: 62AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4cav

- Page 66 and 67: 64AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4was

- Page 68 and 69: 66AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4Fig

- Page 70 and 71: 68AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4199

- Page 72 and 73: 70AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4fir

- Page 74 and 75: 72AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 4by

24AMCS Bulletin 12 — Chapter 2Fedick et al. 2000; Fedick and Taube 1995; see alsoLazcano-Barrero et al. 1995). Well-drained portionsof the region are covered with thin lithosols and pocketsof deeper rendzina soils. Fedick and Hovey (1995)provide a sample distribution of what local milperosrefer to as box luum (productive “black soils”) andchaac luum (less productive “red soils”). Soils withinthe inundated wetlands are characterized by silty claylaminae with overlying peaty deposits (Fedick et al.2000). Throughout northern Quintana Roo, the deepestsoils are found within a variety of karstic depressions.Vegetation zones range from seasonal or perennialwetlands (sabanas) and swamp <strong>for</strong>ests (tintale)to upland, semi-deciduous tropical <strong>for</strong>ests. For in<strong>for</strong>mationon the ancient manipulation of the region’swetlands, see Fedick (1998), Fedick et al. (2000), andMorrison (2000). For a comprehensive overview ofthe region’s ecology, see Gómez-Pompa et al. (2001).Previous and Current ArchaeologicalInvestigationsThe Yalahau RegionArchaeological reporting from the Yalahau regiondid not appear until 1946, when Alberto EscalonaRamos described his brief visit to Kantunilkin. Sanders(1955, 1960) conducted the first archaeologicalreconnaissance of the region and provides the resultsof surface collections and minor excavations atChiquilá, Monte Bravo, Solferino, Vista Alegre, ElDiez, Leona Vicario, and Kantunilkin (see figure 2.1).The coastal survey by Eaton and Ball (1978) includesthe site of Vista Alegre, which is located on the LagunaYalahau, along the region’s northern boundary.These and other investigations across northernQuintana Roo are summarized by Anthony P. Andrews(1985). A later report on the site of San Angel (seefigure 2.1) was prepared by Taube and GallaretaNegrón (1989). Previous and subsequent trips to theregion by Karl A. Taube, Fernando Cortés deBrasdefer, Edward Kurjack, Rubén Maldonado, SoniaLombardo, and Scott L. Fedick were motivated by adeveloping appreciation <strong>for</strong> the rich and enigmaticarchaeological landscape of the Yalahau region.As is evident, the Yalahau region proper had receivedlittle archaeological attention prior to the <strong>for</strong>mationof the Yalahau Regional Human Ecology Project in1993. Research conducted during the initial field seasonwas centered in and around the civic-ceremonialcenter of El Naranjal (also referred to as Tumben-Naranjal; see figure 2.2). For a more comprehensiveintroduction to the Yalahau region as well as the resultsFigure 2.1. Sites of the Yalahau Region.of the multifaceted 1993 season, the reader shouldconsult Fedick and Taube (eds.1995).The unique Megalithic architecture at El Naranjal(and nearby sites) was first studied by Taube (1995).This style is reminiscent of Aké and Izamal to the westand is believed to correspond to the Late Preclassic toEarly Classic periods (Taube 1995; see also AndrewsIV and Stuart 1975:80; Roys and Shook 1966:49–50;Sidrys 1978:157; Velázquez Morlet et al. 1991:61;Webster 1979:156–157). In her authoritative study ofthe nature and distribution of the Megalithic styleacross the northern Maya Lowlands, Mathews (1998)evaluated the extent to which this style is suggestiveof a northern interaction sphere during this early timeframe. Issues relating to the identification or designationof interaction spheres that at one time includednorthern Quintana Roo are briefly discussed below.Additional research at El Naranjal between 1995and 1999 involved excavation of the site’s sascaberas(Lorenzen 1998, 1999), recordation of Postclassicmodification to the site’s monumental architecture(Lorenzen 1999), and identification of outlying settlementsand topographic features (Rissolo 1998a).During this same period, a new program of reconnaissanceand mapping was initiated in the northernportion of the Yalahau region. Extensive early settlement