Use of algae and aquatic macrophytes as feed in small-scale ... - FAO

Use of algae and aquatic macrophytes as feed in small-scale ... - FAO

Use of algae and aquatic macrophytes as feed in small-scale ... - FAO

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

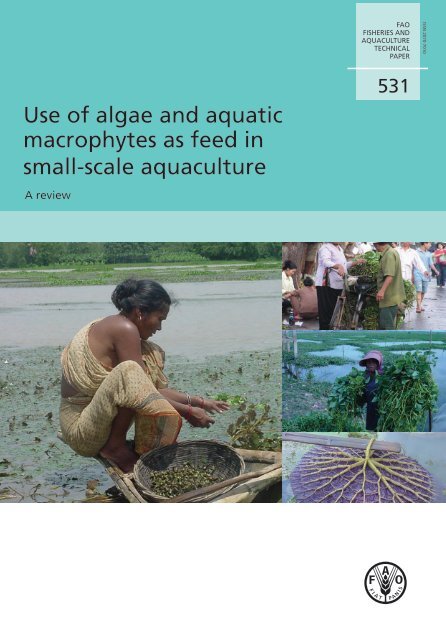

<strong>FAO</strong>FISHERIES ANDAQUACULTURETECHNICALPAPERISSN 2070-7010<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong><strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquacultureA review531isrlyforpmentopg:workributions;icators.catorreedcial,

Cover photographs:Left: Woman collect<strong>in</strong>g water chestnut fruits from a floodpla<strong>in</strong>, Rangpur, Bangladesh (courtesy <strong>of</strong>Mohammad R. H<strong>as</strong>an).Right top to bottom: Sale <strong>of</strong> water sp<strong>in</strong>ach leaves, Ho Chi M<strong>in</strong>h City, Viet Nam (courtesy <strong>of</strong> WilliamLeschen). Woman carry<strong>in</strong>g water sp<strong>in</strong>ach leaves after harvest, Beung Cheung Ek w<strong>as</strong>tewater lake,Phnom Penh, Cambodia (courtesy <strong>of</strong> William Leschen). Back side <strong>of</strong> a lotus leave, photograph taken <strong>in</strong> afloodpla<strong>in</strong>, Rangpur, Bangladesh (courtesy <strong>of</strong> Mohammad R. H<strong>as</strong>an).

<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong><strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquacultureA review<strong>FAO</strong>FISHERIES ANDAQUACULTURETECHNICALPAPER531byMohammad R. H<strong>as</strong>anAquaculture Management <strong>and</strong> Conservation ServiceFisheries <strong>and</strong> Aquaculture Management Division<strong>FAO</strong> Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Aquaculture DepartmentRome, Italy<strong>and</strong>R<strong>in</strong>a ChakrabartiUniversity <strong>of</strong> DelhiDelhi, IndiaFOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONSRome, 2009

iiiPreparation <strong>of</strong> this documentRecogniz<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>g importance <strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquaculture, the global review on this topic w<strong>as</strong> undertaken <strong>as</strong> a part <strong>of</strong> theregular work programme <strong>of</strong> the Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Aquaculture Department <strong>of</strong> the Food <strong>and</strong>Agriculture Organization <strong>of</strong> the United Nations (<strong>FAO</strong>) by the Aquaculture Management<strong>and</strong> Conservation Service ‘Study <strong>and</strong> analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>and</strong> nutrients (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g fertilizers)for susta<strong>in</strong>able aquaculture development’. This w<strong>as</strong> carried out under the programme entity‘Monitor<strong>in</strong>g, Management <strong>and</strong> Conservation <strong>of</strong> Resources for Aquaculture Development’.The manuscript w<strong>as</strong> edited for technical content by Michael B. New. For consistency <strong>and</strong>conformity, scientific <strong>and</strong> English common names <strong>of</strong> fish species were used from FishB<strong>as</strong>e(www.fishb<strong>as</strong>e.org/home.htm). Most <strong>of</strong> the photographs <strong>in</strong> the manuscripts were providedby the first author. Where this is not the c<strong>as</strong>e, due acknowledgements are made to thecontributor(s) or the source(s).Special thanks are due to Dr Albert G.J. Tacon (Universidad de L<strong>as</strong> Palm<strong>as</strong> de GranCanaria, Spa<strong>in</strong>), Dr M.A.B. Habib (Bangladesh Agricultural University, Bangladesh), Md.Ghulam Kibria (M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Mar<strong>in</strong>e Resources, Namibia) <strong>and</strong> Dr KhondkerMoniruzzaman (University <strong>of</strong> Dhaka, Bangladesh) who k<strong>in</strong>dly provided papers <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>formation. The Royal Netherl<strong>and</strong>s Emb<strong>as</strong>sy <strong>in</strong> Dhaka, Bangladesh is acknowledged fork<strong>in</strong>dly provid<strong>in</strong>g the reports <strong>of</strong> the Duckweed Research Project.We acknowledge Ms T<strong>in</strong>a Farmer <strong>and</strong> Ms Françoise Schatto for their <strong>as</strong>sistance <strong>in</strong> qualitycontrol <strong>and</strong> <strong>FAO</strong> house style <strong>and</strong> Mr Juan Carlos Trabucco for layout design. The publish<strong>in</strong>g<strong>and</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> the document were undertaken by <strong>FAO</strong>, Rome.Mr Jiansan Jia, Service Chief, <strong>and</strong> Dr Rohana P. Sub<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>ghe, Senior Fishery ResourcesOfficer (Aquaculture), Aquaculture Management <strong>and</strong> Conservation Service <strong>of</strong> the <strong>FAO</strong>Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Aquaculture Department are also gratefully acknowledged for their support.

ivAbstractThis technical paper presents a global review on the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong>for farmed fish, with particular reference to their current <strong>and</strong> potential use by <strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong>farmers. The review is organized under four major divisions <strong>of</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong>: <strong>algae</strong>,float<strong>in</strong>g <strong>macrophytes</strong>, submerged <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>and</strong> emergent <strong>macrophytes</strong>. Under float<strong>in</strong>g<strong>macrophytes</strong>, Azolla, duckweeds <strong>and</strong> water hyac<strong>in</strong>ths are discussed separately; the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gfloat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>macrophytes</strong> are grouped together <strong>and</strong> are reviewed <strong>as</strong> ‘other float<strong>in</strong>g <strong>macrophytes</strong>’.The review covers <strong>as</strong>pects concerned with the production <strong>and</strong>/or cultivation techniques <strong>and</strong>use <strong>of</strong> the <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>in</strong> their fresh <strong>and</strong>/or processed state <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> for farmed fish. Efficiency<strong>of</strong> <strong>feed</strong><strong>in</strong>g is evaluated by present<strong>in</strong>g data on growth, food conversion <strong>and</strong> digestibility<strong>of</strong> target fish species. Results <strong>of</strong> laboratory <strong>and</strong> field trials <strong>and</strong> on-farm utilization <strong>of</strong><strong>macrophytes</strong> by farmed fish species are presented. The paper provides <strong>in</strong>formation on thedifferent process<strong>in</strong>g methods employed (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g compost<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> fermentation) <strong>and</strong> resultsobta<strong>in</strong>ed to date with different species throughout the world with particular reference toAsia. F<strong>in</strong>ally, it gives <strong>in</strong>formation on the proximate <strong>and</strong> chemical composition <strong>of</strong> mostcommonly occurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>macrophytes</strong>, their cl<strong>as</strong>sification <strong>and</strong> their geographical distribution<strong>and</strong> environmental requirements.H<strong>as</strong>an, M.R.; Chakrabarti, R.<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquaculture: a review.<strong>FAO</strong> Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Aquaculture Technical Paper. No. 531. Rome, <strong>FAO</strong>. 2009. 123p.

vi6. Submerged <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> 75Cl<strong>as</strong>sification 75Characteristics 75Production 76Chemical composition 76<strong>Use</strong> <strong>as</strong> aqua<strong>feed</strong> 787. Emergent <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> 89Cl<strong>as</strong>sification 89Characteristics 90Production 91Chemical composition 91<strong>Use</strong> <strong>as</strong> aqua<strong>feed</strong> 938. Conclusions 95Algae 95Azolla 95Duckweeds 96Water hyac<strong>in</strong>ths 96Other float<strong>in</strong>g <strong>macrophytes</strong> 97Submerged <strong>macrophytes</strong> 98Emergent <strong>macrophytes</strong> 99References 101Annex 1 Essential am<strong>in</strong>o acid composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> 119Annex 2 Periphyton 123

viiAbbreviations <strong>and</strong> acronymsAPDBFRIBWDMDWDWRPEAAFCRFWMAEPMPNFENGOPRISMSGRTKNTSPUASB2,4-DApparent Prote<strong>in</strong> DigestibilityBangladesh Fishery Research InstituteBody WeightDry Matter b<strong>as</strong>isDry weightDuckweed Research Project (Bangladesh)Essential Am<strong>in</strong>o AcidFeed Conversion RatioFresh WeightMymens<strong>in</strong>gh Aquaculture Extension ProjectMuriate <strong>of</strong> Pot<strong>as</strong>hNitrogen-Free ExtractNon-governmental organizationProject <strong>in</strong> Agriculture, Rural Industry Science <strong>and</strong> Medic<strong>in</strong>e (anNGO)Specific Growth RateTotal Kjeldahl NitrogenTriple Super PhosphateUpflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket Reactor2,4-Dichhlorophenoxyacetic acid

1. AlgaeAlgae have been used <strong>in</strong> animal <strong>and</strong> human diets s<strong>in</strong>ce very early times. Filamentous<strong>algae</strong> are usually considered <strong>as</strong> ‘<strong>macrophytes</strong>’ s<strong>in</strong>ce they <strong>of</strong>ten form float<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>as</strong>ses thatcan be e<strong>as</strong>ily harvested, although many consist <strong>of</strong> microscopic, <strong>in</strong>dividual filaments<strong>of</strong> algal cells. Algae also form a component <strong>of</strong> periphyton, which not only providesnatural food for fish <strong>and</strong> other <strong>aquatic</strong> animals but is actively promoted by fishers <strong>and</strong>aquaculturists <strong>as</strong> a means <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>g productivity. This topic is not dealt with <strong>in</strong>this section, s<strong>in</strong>ce periphyton is not solely comprised <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> certa<strong>in</strong>ly cannot beregarded <strong>as</strong> macro<strong>algae</strong>. However, some ancillary <strong>in</strong>formation on this topic is provided<strong>in</strong> Annex 2 to <strong>as</strong>sist with further read<strong>in</strong>g. Mar<strong>in</strong>e ‘seaweeds’ are macro-<strong>algae</strong> that havedef<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>and</strong> characteristic structures.Microalgal biotechnology only really began to develop <strong>in</strong> the middle <strong>of</strong> the l<strong>as</strong>tcentury but it h<strong>as</strong> numerous commercial applications. Algal products can be usedto enhance the nutritional value <strong>of</strong> food <strong>and</strong> animal <strong>feed</strong> ow<strong>in</strong>g to their chemicalcomposition; they play a crucial role <strong>in</strong> aquaculture. Macroscopic mar<strong>in</strong>e <strong>algae</strong>(seaweeds) for human consumption, especially nori (Porphyra spp.), wakame (Undariap<strong>in</strong>natifida), <strong>and</strong> kombu (Lam<strong>in</strong>aria japonica), are widely cultivated algal crops. Themost widespread application <strong>of</strong> microalgal culture h<strong>as</strong> been <strong>in</strong> artificial food cha<strong>in</strong>ssupport<strong>in</strong>g the husb<strong>and</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> mar<strong>in</strong>e animals, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>fish, crustaceans, <strong>and</strong>molluscs.The culture <strong>of</strong> seaweed is a grow<strong>in</strong>g worldwide <strong>in</strong>dustry, produc<strong>in</strong>g 14.5 milliontonnes (wet weight) worth US$7.54 billion <strong>in</strong> 2007 (<strong>FAO</strong>, 2009). The use <strong>of</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong><strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>in</strong> treat<strong>in</strong>g sewage effluents h<strong>as</strong> also shown potential. In recent years,macro<strong>algae</strong> have been <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>gly used <strong>as</strong> animal fodder supplements <strong>and</strong> for theproduction <strong>of</strong> alg<strong>in</strong>ate, which is used <strong>as</strong> a b<strong>in</strong>der <strong>in</strong> <strong>feed</strong>s for farm animals. Laboratory<strong>in</strong>vestigations have also been carried out to evaluate both <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> macro<strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong>possible alternative prote<strong>in</strong> sources for farmed fish because <strong>of</strong> their high prote<strong>in</strong> content<strong>and</strong> productivity.Micro<strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> macro<strong>algae</strong> are also used <strong>as</strong> components <strong>in</strong> polyculture systems<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> remediation; although these topics are not covered <strong>in</strong> this paper, <strong>in</strong>formationon bioremediation is conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> many publications, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Msuya <strong>and</strong> Neori(2002), Zhou et al. (2006) <strong>and</strong> Mar<strong>in</strong>ho-Soriano (2007). Red seaweed (Gracilaria spp.)<strong>and</strong> green seaweed (Ulva spp.) have been found to suitable species for bioremediation.The use <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrated aquaculture h<strong>as</strong> also been recently reviewed by Turan(2009).1.1 Cl<strong>as</strong>sificationThe cl<strong>as</strong>sification <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> is complex <strong>and</strong> somewhat controversial, especially concern<strong>in</strong>gthe blue-green <strong>algae</strong> (Cyanobacteria), which are sometimes known <strong>as</strong> blue-greenbacteria or Cyanophyta <strong>and</strong> sometimes <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the Chlorophyta. These topics arenot covered <strong>in</strong> detail this document. However, the follow<strong>in</strong>g provides a taxonomicaloutl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong>.Archaepl<strong>as</strong>tida• Chlorophyta (green <strong>algae</strong>)• Rhodophyta (red <strong>algae</strong>)• GlaucophytaRhizaria, Excavata• Chlorarachniophytes

<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquaculture – A reviewAnother green filamentous alga, Hydrodictyon, commonly known <strong>as</strong> ‘water net’,belongs to the family Hydrodictyaceae <strong>and</strong> prefers clean, eutrophic water. Its namerefers to its shape, which looks like a netlike hollow sack (Figure 1.4) <strong>and</strong> can growup to several decimetres.1.2.2 SeaweedsUlva are th<strong>in</strong> flat green <strong>algae</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g from a discoid holdf<strong>as</strong>t that may reach 18 cm ormore <strong>in</strong> length, though generally much less, <strong>and</strong> up to 30 cm across. The membrane istwo cells thick, s<strong>of</strong>t <strong>and</strong> translucent <strong>and</strong> grows attached (without a stipe) to rocks bya <strong>small</strong> disc-shaped holdf<strong>as</strong>t. The water lettuce (Ulva lactuca) is green to dark green<strong>in</strong> colour (Figure 1.5). There are other species <strong>of</strong> Ulva that are similar <strong>and</strong> difficult todifferentiate.Figure 1.5Sea lettuce (Ulva lactuca)Figure 1.6Eucheuma cottoniiSource: M<strong>and</strong>y L<strong>in</strong>deberg (www.seaweeds<strong>of</strong>al<strong>as</strong>ka.com)Source: www.acts<strong>in</strong>c.biz/seaweed.htmlIt is important to recognize that the genera Eucheuma <strong>and</strong> Kappaphycus arenormally grouped together; their taxonomical cl<strong>as</strong>sification is contentious. These arered seaweeds <strong>and</strong> are <strong>of</strong>ten very large macro<strong>algae</strong> that grow rapidly. The systematics<strong>and</strong> taxonomy <strong>of</strong> Kappaphycus <strong>and</strong> Eucheuma (Figure 1.6) is confused <strong>and</strong> difficult, dueto morphological pl<strong>as</strong>ticity, lack <strong>of</strong> adequate characters to identify species <strong>and</strong> the use<strong>of</strong> commercial names <strong>of</strong> convenience. These taxa are geographically widely dispersedthrough cultivation (Zuccarello et al., 2006). These red seaweeds are widely cultivated,particularly to provide a source <strong>of</strong> carageenan, which is used <strong>in</strong> the manufacture <strong>of</strong>food, both for humans <strong>and</strong> other animals.Gracilaria is another genus <strong>of</strong> red <strong>algae</strong> (Figure 1.7), most well-known for itseconomic importance <strong>as</strong> a source <strong>of</strong> agar, <strong>as</strong> well <strong>as</strong> its use <strong>as</strong> a food for humans.Figure 1.7Gracilaria sp.Figure 1.8Porphyra teneraSource: Eric Moody© (Wikipedia)Source: http://www.fao.org/fishery/species/search/en

AlgaeThe red seaweed Porphyra (Figure 1.8) is known by many local names, such <strong>as</strong> laveror nori, <strong>and</strong> there are about 100 species. This genus h<strong>as</strong> been cultivated extensively <strong>in</strong>many Asian countries <strong>and</strong> is used to wrap the rice <strong>and</strong> fish that compose the Japanesefood sushi, <strong>and</strong> the Korean food gimbap. It is also used to make the traditional Welshdelicacy, laverbread.1.3 ProductionAs <strong>in</strong> the c<strong>as</strong>e <strong>of</strong> their environmental conditions, the methods for cultur<strong>in</strong>g filamentous<strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> seaweeds vary widely, accord<strong>in</strong>g to species <strong>and</strong> location. This topic is notcovered <strong>in</strong> this review but there are many publications available on algal culturegenerally, such <strong>as</strong> the <strong>FAO</strong> manual on the production <strong>of</strong> live food for aquaculture byLavens <strong>and</strong> Sorgeloos (1996). Concern<strong>in</strong>g seaweed culture, the follow<strong>in</strong>g summary<strong>of</strong> the techniques used h<strong>as</strong> been h<strong>as</strong> been extracted from another <strong>FAO</strong> publication(McHugh, 2003) <strong>and</strong> further read<strong>in</strong>g on seaweed culture can also be found <strong>in</strong> McHugh(2002).Some seaweeds can be cultivated vegetatively, others only by go<strong>in</strong>g through a separatereproductive cycle, <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g alternation <strong>of</strong> generations.In vegetative cultivation, <strong>small</strong> pieces <strong>of</strong> seaweed are taken <strong>and</strong> placed <strong>in</strong> anenvironment that will susta<strong>in</strong> their growth. When they have grown to a suitable size theyare harvested, either by remov<strong>in</strong>g the entire plant or by remov<strong>in</strong>g most <strong>of</strong> it but leav<strong>in</strong>ga <strong>small</strong> piece that will grow aga<strong>in</strong>. When the whole plant is removed, <strong>small</strong> pieces are cutfrom it <strong>and</strong> used <strong>as</strong> seedstock for further cultivation. The suitable environment variesamong species, but must meet requirements for sal<strong>in</strong>ity <strong>of</strong> the water, nutrients, watermovement, water temperature <strong>and</strong> light. The seaweed can be held <strong>in</strong> this environment<strong>in</strong> several ways: pieces <strong>of</strong> seaweed may be tied to long ropes suspended <strong>in</strong> the waterbetween wooden stakes, or tied to ropes on a float<strong>in</strong>g wooden framework (a raft);sometimes nett<strong>in</strong>g is used <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong> ropes; <strong>in</strong> some c<strong>as</strong>es the seaweed is simply placedon the bottom <strong>of</strong> a pond <strong>and</strong> not fixed <strong>in</strong> any way; <strong>in</strong> more open waters, one k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong>seaweed is either forced <strong>in</strong>to the s<strong>of</strong>t sediment on the sea bottom with a fork-like tool,or held <strong>in</strong> place on a s<strong>and</strong>y bottom by attach<strong>in</strong>g it to s<strong>and</strong>-filled pl<strong>as</strong>tic tubes.Cultivation <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g a reproductive cycle, with alternation <strong>of</strong> generations, isnecessary for many seaweeds; for these, new plants cannot be grown by tak<strong>in</strong>gcutt<strong>in</strong>gs from mature ones. This is typical for many <strong>of</strong> the brown seaweeds, <strong>and</strong>Lam<strong>in</strong>aria species are a good example; their life cycle <strong>in</strong>volves alternation between alarge sporophyte <strong>and</strong> a microscopic gametophyte-two generations with quite differentforms. The sporophyte is what is harvested <strong>as</strong> seaweed, <strong>and</strong> to grow a new sporophyteit is necessary to go through a sexual ph<strong>as</strong>e <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g the gametophytes. The maturesporophyte rele<strong>as</strong>es spores that germ<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>and</strong> grow <strong>in</strong>to microscopic gametophytes.The gametophytes become fertile, rele<strong>as</strong>e sperm <strong>and</strong> eggs that jo<strong>in</strong> to form embryonicsporophytes. These slowly develop <strong>in</strong>to the large sporophytes that we harvest. Thepr<strong>in</strong>cipal difficulties <strong>in</strong> this k<strong>in</strong>d <strong>of</strong> cultivation lie <strong>in</strong> the management <strong>of</strong> the transitionsfrom spore to gametophyte to embryonic sporophyte; these transitions are usuallycarried out <strong>in</strong> l<strong>and</strong>-b<strong>as</strong>ed facilities with careful control <strong>of</strong> water temperature, nutrients<strong>and</strong> light. The high costs <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> this can be absorbed if the seaweed is sold <strong>as</strong>food, but the cost is normally too high for production <strong>of</strong> raw material for alg<strong>in</strong>ateproduction.Where cultivation is used to produce seaweeds for the hydrocolloid <strong>in</strong>dustry (agar<strong>and</strong> carrageenan), the vegetative method is mostly used, while the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal seaweedsused <strong>as</strong> food must be taken through the alternation <strong>of</strong> generations for their cultivation.

<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquaculture – A review1.4 Chemical compositionA summary <strong>of</strong> the chemical composition <strong>of</strong> various filamentous <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> seaweeds ispresented <strong>in</strong> Table 1.1. Algae are receiv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>g attention <strong>as</strong> possible alternativeprote<strong>in</strong> sources for farmed fish, particularly <strong>in</strong> tropical develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, because<strong>of</strong> their high prote<strong>in</strong> content (especially the filamentous blue-green <strong>algae</strong>).The dry matter b<strong>as</strong>is (DM) analyses reviewed <strong>in</strong> Table 1.1 show that the prote<strong>in</strong>levels <strong>of</strong> filamentous blue green <strong>algae</strong> ranged from 60–74 percent. Those for filamentousgreen <strong>algae</strong> were much lower (16–32 percent). The prote<strong>in</strong> contents <strong>of</strong> green <strong>and</strong> redseaweeds were quite variable, rang<strong>in</strong>g from 6–26 percent <strong>and</strong> 3–29 percent respectively.The levels reported for Eucheuma/ Kappaphycus were very low, rang<strong>in</strong>g from 3–10percent, but the results for Gracilaria, with one exception, were much higher (16–20percent). The one analysis for Porphyra <strong>in</strong>dicated that it had a prote<strong>in</strong> level (29 percent)comparable to filamentous green <strong>algae</strong>. Some <strong>in</strong>formation on the am<strong>in</strong>o acid content <strong>of</strong>various <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> is conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> Annex 1.The lipid levels reported for Spirul<strong>in</strong>a (Table 1.1), with one exception (Olvera-Novoa et al. (1998), were between <strong>and</strong> 4 <strong>and</strong> 7 percent. Those for filamentous green<strong>algae</strong> varied more widely (2–7 percent). The lipid contents <strong>of</strong> both green (0.3–3.2percent) <strong>and</strong> red seaweeds (0.1–1.8 percent) were generally much lower than those <strong>of</strong>filamentous <strong>algae</strong>. The <strong>as</strong>h content <strong>of</strong> filamentous blue-green <strong>algae</strong> ranged from 3–11percent but those <strong>of</strong> filamentous green <strong>algae</strong> were generally much higher, rang<strong>in</strong>g fromjust under 12 percent to one sample <strong>of</strong> Cladophora that had over 44 percent. The <strong>as</strong>hcontents <strong>of</strong> green seaweeds ranged from 12–31 percent. Red seaweeds had an extremelywide range <strong>of</strong> <strong>as</strong>h contents (4 to nearly 47 percent) <strong>and</strong> generally had higher levels thanthe other <strong>algae</strong> shown <strong>in</strong> Table 1.1.1.5 <strong>Use</strong> <strong>as</strong> aqua<strong>feed</strong>Several <strong>feed</strong><strong>in</strong>g trials have been carried out to evaluate <strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong> fish <strong>feed</strong>. Algae havebeen used fresh <strong>as</strong> a whole diet <strong>and</strong> dried algal meal h<strong>as</strong> been used <strong>as</strong> a partial orcomplete replacement <strong>of</strong> fishmeal prote<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> pelleted diets.1.5.1 Algae <strong>as</strong> major dietary <strong>in</strong>gredientsA summary <strong>of</strong> the results <strong>of</strong> selected growth studies on the use <strong>of</strong> fresh <strong>algae</strong> or dry<strong>algae</strong> meals <strong>as</strong> major dietary <strong>in</strong>gredients for various fish species <strong>and</strong> one mar<strong>in</strong>e shrimpis presented <strong>in</strong> Table 1.2. Dietary <strong>in</strong>clusion levels <strong>in</strong> these studies varied from 5 to 100percent. Fishmeal-b<strong>as</strong>ed dry pellets or moist diets were used <strong>as</strong> control diets.The results <strong>of</strong> the earlier growth studies showed that the performances <strong>of</strong> fish feddiets conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 10–20 percent <strong>algae</strong> or seaweed meal were similar to those fed fishmealb<strong>as</strong>ed st<strong>and</strong>ard control diet. The responses were apparently similar for most <strong>of</strong> thefish species tested. These <strong>in</strong>clusion levels effectively supplied only about 3–5 percentprote<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> the control diet. In most c<strong>as</strong>es, these control diets conta<strong>in</strong>ed about 26–47percent crude prote<strong>in</strong>. This shows that only about 10–15 percent <strong>of</strong> dietary prote<strong>in</strong>requirement can be met by <strong>algae</strong> without compromis<strong>in</strong>g growth <strong>and</strong> food utilization.There w<strong>as</strong> a progressive decre<strong>as</strong>e <strong>in</strong> fish performance when dietary <strong>in</strong>corporation <strong>of</strong>algal meal rose above 15–20 percent. However, although reduced growth responseswere recorded with <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>in</strong> the diet, the results <strong>of</strong> <strong>feed</strong><strong>in</strong>g trialswith filamentous green <strong>algae</strong> for O. niloticus <strong>and</strong> T. zillii <strong>in</strong>dicated that SGR <strong>of</strong> 60–80percent <strong>of</strong> the control diet could be achieved with dietary <strong>in</strong>clusion levels <strong>as</strong> high <strong>as</strong>50–70 percent.Recent work by Kalla et al. (2008) appears to <strong>in</strong>dicate that the addition <strong>of</strong> Porphyr<strong>as</strong>pheropl<strong>as</strong>ts to a semi-purified red seabream diet improved SGR. In addition, Valenteet al. (2006) recorded improvements <strong>in</strong> SGR when dried Gracilaria busra-p<strong>as</strong>tonisreplaced 5 or 10 percent <strong>of</strong> a fish prote<strong>in</strong> hydrolysate diet for European seab<strong>as</strong>s.

AlgaeTable 1.1Chemical analyses <strong>of</strong> some common <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> seaweedsAlgae/ seaweed Moisture(percent)Proximate composition 1(percent DM)M<strong>in</strong>erals 1(percent DM)CP EE Ash CF NFE Ca PFilamentous blue-green <strong>algae</strong>Spirul<strong>in</strong>a maxima, spray dried powder 6.0 63.8 5.3 9.6 n.s. n.s. n.s. Henson (1990)Spirul<strong>in</strong>a, commercial dry powder 3-6 60.0 5.0 7.0 7.0 21.0 n.s. n.s. Habib et al. (2008)Spirul<strong>in</strong>a spp., dry powder n.s. 55-70 4-7 3-11 3-7 n.s. n.s. Habib et al. (2008)Spirul<strong>in</strong>a maxima, dry powder, Mexico 10.2 73.7 0.7 10.5 2.1 13.0 n.s. n.s. Olvera-Nova et al. (1998)Filamentous green <strong>algae</strong>Spirogyra spp., fresh, USA 95.2 17.1 1.8 11.7 10.0 2 n.s. n.s. Boyd (1968)Cladophora glomerata, meal, Scotl<strong>and</strong> 1.6 31.6 5.2 23.6 11.2 28.4 n.s. n.s. Appler <strong>and</strong> Jauncey (1983)Cladophora sp., fresh, USA 3 90.5 15.8 2.1 44.3 13.3 424.5 n.s. n.s. P<strong>in</strong>e, Anderson <strong>and</strong> Hung (1989)Hydrodictyon reticulatum, fresh, USA 96.1 22.8 7.1 11.9 18.1 2 n.s. n.s. Boyd (1968)Hydrodictyon reticulatum, meal, Belgium 5.7 27.7 1.9 32.6 14.9 22.9 n.s. n.s. Appler (1985)Green seaweedsUlva reticulata, fresh, Tanzania n.s. 25.7 n.s. 18.3 38.5 n.s. 0.1 Msuya <strong>and</strong> Neori (2002)Ulvaria oxysperma, dried, Brazil 16-20 6-10 0.5-3.2 17-31 3-12 n.s. n.s. Pádua, Fontoura <strong>and</strong> Mathi<strong>as</strong> (2004)Ulva lactuca, dried, Brazil 15-18 15-18 1.2-1.8 12-13 9-12 n.s. n.s. Pádua, Fontoura <strong>and</strong> Mathi<strong>as</strong> (2004)Ulva f<strong>as</strong>cita, dried, Brazil 18-20 13-16 0.3-1.9 17-20 9-11 n.s. n.s. Pádua, Fontoura <strong>and</strong> Mathi<strong>as</strong> (2004)Red seaweedsEucheuma cottonii, fresh, Indonesia 91.3 4.9 0.4 43.5 8.4 42.8 4 0.5 0.2 Tacon et al. (1990)Eucheuma cottonii, dry powder, Malaysia 10.6 9.8 1.1 46.2 5.9 37.0 4 0.3 n.s. Matanjun et al. (2009)Eucheuma denticulatum, fresh, Tanzania n.s. 7.6 n.s. 46.6 22.3 n.s.

10<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquaculture – A reviewTable 1.2Performance <strong>of</strong> various fish species fed fresh <strong>algae</strong> or dried algal mealAlgae/ fish species Rear<strong>in</strong>gsystemFilamentous green <strong>algae</strong>Rear<strong>in</strong>gdaysControl diet Composition <strong>of</strong> test diet Inclusionlevel(percent)Fish size(g)SGR(percent)SGR <strong>as</strong>percent <strong>of</strong>controlFCR ReferencesCladophora glomerata/ Niletilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)Hydrodictyon reticulatum/Nile tilapia (Oreochromisniloticus)Hydrodictyon reticulatum/Redbelly tilapia (Tilapia zillii)Filamentous blue-green <strong>algae</strong>Spirul<strong>in</strong>a/ Java tilapia(Oreochromis mossambicus)SeaweedsPorphyra purpurea/ thicklippedgrey mullet (Chelonlabrosus)LaboratoryrecirculatorysystemLaboratoryrecirculatorysystemLaboratoryrecirculatorysystemIndoor statictankFlow-throughsystem56 Fish meal b<strong>as</strong>edpellet (30percent prote<strong>in</strong>)50 Fish meal b<strong>as</strong>edpellet (30percent prote<strong>in</strong>)50 Fishmeal b<strong>as</strong>edpellet (30percent prote<strong>in</strong>)25 Fishmeal b<strong>as</strong>edmoist diet (26percent prote<strong>in</strong>)70 Fishmeal b<strong>as</strong>edpellet (47percent prote<strong>in</strong>)5, 10, 15 <strong>and</strong> 20 percentprote<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> control <strong>feed</strong>replaced by algal meal <strong>and</strong>one diet prepared by algalmeal <strong>as</strong> the only sources<strong>of</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> (25 percentprote<strong>in</strong>)5, 10, 15 <strong>and</strong> 20 percentprote<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> control <strong>feed</strong>replaced by algal meal <strong>and</strong>one diet prepared by algalmeal <strong>as</strong> the only sources<strong>of</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> (25 percentprote<strong>in</strong>)5, 10, 15 <strong>and</strong> 20 percentprote<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> control <strong>feed</strong>replaced by algal meal <strong>and</strong>one diet prepared by algalmeal <strong>as</strong> the only sources<strong>of</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> (25 percentprote<strong>in</strong>)11 percent fishmealreplaced by Spirul<strong>in</strong>a meal4.5 <strong>and</strong> 9.0 percent prote<strong>in</strong><strong>of</strong> control <strong>feed</strong> replaced byseaweed meal16.1 1.88-2.09 3.11 97.5 1.21 Appler <strong>and</strong>Jauncey(1983)32.3 2.80 87.8 1.4248.4 2.77 86.8 1.5164.5 2.06 64.6 2.0982.5 1.85 58.0 2.3319.2 0.92-1.04 2.22 91.7 1.83 Appler38.3 1.85 76.4 2.18 (1985)57.5 1.48 61.2 2.4970.6 1.52 62.8 2.6398.5 1.07 44.2 3.6019.2 0.91-1.16 2.04 107.9 2.09 Appler38.3 1.73 91.5(1985)57.5 1.45 76.770.6 1.44 76.298.5 1.05 55.611.0 7.4-8.3 1.96 101.0 - Chow <strong>and</strong>Woo (1996)16.5 1.15 2.65 88.6 2.06 Davies,33.0 1.15 2.47 82.6 2.28 Brown <strong>and</strong>Camilleri(1997)

Algae 11TABLE 1.2 (cont.)Performance <strong>of</strong> various fish species fed fresh <strong>algae</strong> or dried algal mealAlgae/ fish species Rear<strong>in</strong>g system Rear<strong>in</strong>gdaysPorphyra sp./ Red seabream(Pagrus major)Ulva rigida/ European seab<strong>as</strong>s(Dicentrarchus labrax)Gracilaria cornea/ Europeanseab<strong>as</strong>s (Dicentrarchus labrax)Gracilaria busra-p<strong>as</strong>tonis/European seab<strong>as</strong>s(Dicentrarchus labrax)Gracilaria lichenoides/ rabbitfish(Siganus canaliculatus)Eucheuma cottonii/ rabbitfish(Siganus canaliculatus)Gracilaria sp./ Giant tigerprawns (Penaeus monodon)Flow-throughsystemRecirculationsystemRecirculationsystemRecirculat<strong>in</strong>gsystemFloat<strong>in</strong>g netcagesFloat<strong>in</strong>g netcagesBrackishwaterrecirculatorysystemControl diet Composition <strong>of</strong> test diet Inclusionlevel(percent)42 Fishmeal b<strong>as</strong>edsemi-purifieddiet (51 percentprote<strong>in</strong>)70 Fish prote<strong>in</strong>hydrolysate b<strong>as</strong>eddiet (60.8 percentprote<strong>in</strong>)70 Fish prote<strong>in</strong>hydrolysate b<strong>as</strong>eddiet (60.8 percentprote<strong>in</strong>)70 Fish prote<strong>in</strong>hydrolysate b<strong>as</strong>eddiet (60.8 percentprote<strong>in</strong>)100 Carp starterpellet (27 percentprote<strong>in</strong>)100 Carp starterpellet (27 percentprote<strong>in</strong>)60 Soybean <strong>and</strong>fish meal b<strong>as</strong>eddiet (35 percentprote<strong>in</strong>)5 percent Porphyr<strong>as</strong>pheropl<strong>as</strong>ts added to diet5 <strong>and</strong> 10 percent fishprote<strong>in</strong> hydrolysate replacedby dried seaweed5 <strong>and</strong> 10 percent fishprote<strong>in</strong> hydrolysate replacedby dried seaweed5 <strong>and</strong> 10 percent fishprote<strong>in</strong> hydrolysate replacedby dried seaweedFresh live seaweed w<strong>as</strong> fed<strong>as</strong> sole dietFresh live seaweed w<strong>as</strong> fed<strong>as</strong> sole diet1, 2, 3 <strong>and</strong> 6 percent prote<strong>in</strong><strong>of</strong> control <strong>feed</strong> replaced byseaweed meal. Seaweedmeal <strong>in</strong>corporated byreplac<strong>in</strong>g soybean meal <strong>and</strong>wheat flourFishsize(g)SGR(percent)SGR <strong>as</strong>percent<strong>of</strong>controlFCR References5.0 15.4 3.47 111.6 1.52 Kalla et al.(2008)5.0 4.7 2.63 89.8 1.68 Valente et10.0 4.7 2.54 86.7 1.80 al. (2006)5.0 4.7 2.63 89.8 1.74 Valente et10.0 4.7 1.78 60.8 2.31 al. (2006)5.0 4.7 2.98 101.7 1.56 Valente et10.0 4.7 3.37 115.0 1.48 al. (2006)100.0 50.1 Negative growth displayed.SGR <strong>of</strong> control 0.63 percent100.0 48.8 Negative growth displayed.SGR <strong>of</strong> control 0.63 percentTacon et al.(1990)Tacon et al.(1990)5.0 0.024 7.88 98.3 3.33 Briggs <strong>and</strong>10.0 8.03 100.1 3.35 Funge-15.0 7.88 98.3 3.50 Smith(1996)30.0 7.33 91.4 4.14

12<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquaculture – A reviewTable 1.3Results <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>vestigations on the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong> additives <strong>in</strong> fish <strong>feed</strong>Algae 1 Inclusionlevel (percent)Blue-green <strong>algae</strong>Fish species Effect ReferencesSpirul<strong>in</strong>a 2.0 Red sea bream Improved carc<strong>as</strong>s quality through modification <strong>of</strong> muscle lipids Mustafa et al. (1994a)Spirul<strong>in</strong>a maxima 20.9 [40.0replacement<strong>of</strong> fish meal]Brown <strong>algae</strong>Ascophyllumnodosum2.0 Red sea bream Improved muscle quality; <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>ed firmness <strong>and</strong> robustness <strong>of</strong> raw meat; <strong>and</strong> improvedgrowth <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> synthetic activity5.0 Red sea bream Elevated growth rates; improved <strong>feed</strong> conversion, prote<strong>in</strong> efficiency <strong>and</strong> muscle prote<strong>in</strong>depositionMustafa, Um<strong>in</strong>o <strong>and</strong>Nakagawa (1994)Mustafa et al. (1994b)5.0 Nibbler Improved growth Nakazoe et al. (1986)… Striped jack Improved flesh texture <strong>and</strong> t<strong>as</strong>te Liao et al. (1990)2.5 Cherry salmon Elevated growth rates, bright sk<strong>in</strong> colour <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong> appearance; improved flavour <strong>and</strong> firmfleshHensen (1990)0.5 Yellowtail Incre<strong>as</strong>ed survivability <strong>and</strong> improved weight ga<strong>in</strong> Hensen (1990)MozambiquetilapiaF<strong>in</strong>al body weight, daily weight ga<strong>in</strong>, SGR, <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong>take, PER <strong>and</strong> apparent nitrogenutilization showed no significant differences with control dietOlvera-Novoa et al.(1998)5.0 & 10.0 Red sea bream Improved growth <strong>and</strong> <strong>feed</strong> efficiency at 5 percent <strong>in</strong>clusion level Yone, Furuichi <strong>and</strong>Urano (1986a)5.0 Red sea bream Delayed absorption <strong>of</strong> dietary carbohydrate <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong>. The dietary nutrients are utilized effectively by this delay<strong>in</strong>g effect <strong>of</strong> the seaweed; thus the growth <strong>and</strong> <strong>feed</strong> efficiency <strong>of</strong>red sea bream are improvedYone, Furuichi <strong>and</strong>Urano (1986b)5.0 Red sea bream Elevated growth rates; improved <strong>feed</strong> conversion, prote<strong>in</strong> efficiency <strong>and</strong> muscle prote<strong>in</strong> Mustafa et al. (1994b)deposition5.0 Red sea bream Incre<strong>as</strong>ed growth, <strong>feed</strong> efficiency <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> deposition. Elevated liver glycogen <strong>and</strong> Mustafa et al. (1995)triglyceride accumulation <strong>in</strong> muscle0.5 Yellowtail Prevented a nutritional dise<strong>as</strong>e that causes retardation <strong>of</strong> growth <strong>and</strong> high mortality Nakagawa et al.(1986)Undaria p<strong>in</strong>natifida 5.0 Rockfish Showed prom<strong>in</strong>ent physiological effects on haematocrit value <strong>and</strong> red blood cell number Yi <strong>and</strong> Chang (1994)5.0 & 10.0 Red sea bream Improved growth <strong>and</strong> <strong>feed</strong> efficiency, <strong>and</strong> higher muscle lipid deposition at 5 percent level<strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>clusionYone, Furuichi <strong>and</strong>Urano (1986a)

Algae 13TABLE 1.3 (cont.)Results <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>vestigations on the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong> additives <strong>in</strong> fish <strong>feed</strong>Algae 1 Inclusionlevel (percent)Fish species Effect ReferencesRed <strong>algae</strong>Porphyra yezoensis 5.0 Red sea bream Incre<strong>as</strong>ed growth, <strong>feed</strong> efficiency <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> deposition. Elevated liver glycogen <strong>and</strong> Mustafa et al. (1995)triglyceride accumulation <strong>in</strong> musclePorphyra yezoensis 2.0 Yellowtail Improved flesh quality Morioka et al. (2008)Porphyra spheropl<strong>as</strong>ts 5.0 Red sea bream Survival, growth <strong>and</strong> nutrient retention significantly higher than control Kalla et al. (2008)Green <strong>algae</strong>Ulva conglobata 5.0 Nibbler Improved growth Nakazoe et al. (1986)Ulva pertusa 2.5, 5.0, 10.0& 15.0Black seabreamUlva pertusa extract 10.0 Black seabreamUlva meal diets repressed lipid accumulation <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>traperitoneal body fat without loss<strong>of</strong> growth <strong>and</strong> <strong>feed</strong> efficiency. Fish fed 2.5, 5 <strong>and</strong> 10 percent Ulva meal did not showsignificant body weight loss dur<strong>in</strong>g w<strong>in</strong>ter<strong>in</strong>g. Dur<strong>in</strong>g starvation, lipid reserves werepreferentially mobilized for energyNakagawa et al.(1993)Improved tolerance to hypoxia Nakagawa et al.(1984)Ulva pertusa 5.0 Red sea bream Activated lipid mobilization <strong>and</strong> suppressed prote<strong>in</strong> breakdown observed dur<strong>in</strong>gstarvation for fish fed Ulva meal supplemented diet before starvation. Preferential use <strong>of</strong>glycogen observed5.0 Red sea bream Demonstrated a decre<strong>as</strong>e <strong>in</strong> susceptibility to P<strong>as</strong>teurella piscicida, an elevation <strong>of</strong>phagocytosis <strong>and</strong> spontaneous haemolytic <strong>and</strong> bactericidal activity5.0 Red sea bream Incre<strong>as</strong>ed growth, <strong>feed</strong> efficiency <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> deposition. Elevated liver glycogen <strong>and</strong>triglyceride accumulation <strong>in</strong> muscleNakagawa <strong>and</strong>K<strong>as</strong>ahara (1986)Satoh, Nakagawa <strong>and</strong>K<strong>as</strong>ahara (1987)Mustafa et al. (1995)1Algae were added <strong>as</strong> dried meal <strong>in</strong> all diets except otherwise stated

14<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquaculture – A reviewHowever, the conclusions <strong>of</strong> the latter authors are confused by the fact that the testdiets were not iso-nitrogenous with the control diet; <strong>in</strong> fact test diets had a lowerprote<strong>in</strong> level.Total replacement <strong>of</strong> fishmeal by algal meal showed very poor growth responsesfor O. niloticus (Appler <strong>and</strong> Jauncey, 1983; Appler, 1985) <strong>and</strong> T. zillii (Appler, 1985).Appler <strong>and</strong> Jauncey (1983) recorded a SGR <strong>of</strong> 58 percent <strong>of</strong> control diet when thefilamentous green alga (Cladophora glomerata) meal w<strong>as</strong> used <strong>as</strong> the sole source <strong>of</strong>prote<strong>in</strong> for Nile tilapia. Similarly, Appler (1985) recorded SGRs <strong>of</strong> 44 percent <strong>and</strong> 56percent <strong>of</strong> control diets when the filamentous green alga (Hydrodictyon reticulatum)meal w<strong>as</strong> used <strong>as</strong> the sole source <strong>of</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> for O. niloticus <strong>and</strong> T. zillii.Tacon et al. (1990) used fresh live seaweeds (Gracilaria lichenoides <strong>and</strong> Eucheumacottonii) <strong>as</strong> the total diet for rabbitfish <strong>in</strong> net cages. In both c<strong>as</strong>es negative growth w<strong>as</strong>displayed, although the daily <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong>take w<strong>as</strong> more than the control diet. On a drymatter b<strong>as</strong>is, the daily <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong>take w<strong>as</strong> 1.99 <strong>and</strong> 1.98 g/fish/day respectively forE. cottonii <strong>and</strong> G. lichenoides, while the <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong>take for carp pellets (control diet)w<strong>as</strong> 1.80 g/fish/day. Apparently, a good <strong>feed</strong><strong>in</strong>g response w<strong>as</strong> observed for both theseaweeds but very poor <strong>feed</strong> efficiency w<strong>as</strong> displayed. Apart from commonly observedimpaired growth, the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong> the sole source <strong>of</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> fish <strong>feed</strong> can alsoresult <strong>in</strong> malformation (Meske <strong>and</strong> Pfeffer, 1978).The apparently poor performance <strong>of</strong> fish fed diets conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g higher <strong>in</strong>clusionlevels <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> may be attributable to several factors. Appler (1985) observed that most<strong>of</strong> the <strong>aquatic</strong> plants <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>algae</strong> conta<strong>in</strong> 40 percent or more <strong>of</strong> carbohydrate, <strong>of</strong>which only a <strong>small</strong> fraction consists <strong>of</strong> mono- <strong>and</strong> di-saccharides. Low digestibility<strong>of</strong> plant materials h<strong>as</strong> been attributed to a preponderance <strong>of</strong> complex <strong>and</strong> structuralcarbohydrates. The poor digestibility <strong>and</strong> the subsequent poor levels <strong>of</strong> utilizationobta<strong>in</strong>ed for both tilapia species with <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>ed dietary algal levels may thus beattributable <strong>in</strong> part to the presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>digestible algal materials. Pant<strong>as</strong>tico, Baldia <strong>and</strong>Reyes (1985) reported that newly hatched Nile tilapia fry (mean weight 0.7 mg) did notsurvive at all when unialgal cultures <strong>of</strong> Euglena elongata <strong>and</strong> Chlorella ellipsoidea werefed to them. These authors concluded that the mortality <strong>of</strong> tilapia fry might be due t<strong>of</strong>actors such <strong>as</strong> toxicity <strong>and</strong> cell-wall composition <strong>of</strong> the <strong>algae</strong> fed. This phenomenonmight also be attributed to poor digestion <strong>of</strong> plant material by the less developeddigestive system <strong>of</strong> newly hatched larva. In contr<strong>as</strong>t, Chow <strong>and</strong> Woo (1990) recordedsignificantly higher gut cellul<strong>as</strong>e activity <strong>in</strong> O. mossambicus fed Spirul<strong>in</strong>a, <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g theability <strong>of</strong> this tilapia species to digest cellulose, the ma<strong>in</strong> constituent <strong>of</strong> plant cell walls.Ayyappan et al. (1991) conducted a Spirul<strong>in</strong>a <strong>feed</strong><strong>in</strong>g experiment with carp species. Thefry stage <strong>of</strong> catla (Catla catla), rohu (Labeo rohita), mrigal (Cirrh<strong>in</strong>us mrigala), silvercarp (Hypophthalmicthys molitrix), gr<strong>as</strong>s carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) <strong>and</strong> commoncarp (Cypr<strong>in</strong>us carpio) were fed with an experimental diet <strong>in</strong> which 10 percent driedSpirul<strong>in</strong>a powder w<strong>as</strong> added to a 45:45 mixture <strong>of</strong> rice bran <strong>and</strong> groundnut oil cake. A50:50 bran-groundnut oil cake control diet w<strong>as</strong> used. The mean specific growth rates<strong>of</strong> fish fed on the two diets were: catla 0.17, 0.27; rohu 0.19, 0.63; mrigal 0.54, 0.73;gr<strong>as</strong>s carp 0.02, 0.40; <strong>and</strong> common carp 0.15, 0.20; with significant differences betweenthe treatments (F 1,4 = 8.88; P < 0.05) <strong>and</strong> fish species (F 4,4 = 5.03; P < 0.10). Rohu <strong>and</strong>mrigal showed significantly (P < 0.05) higher SGRs than catla <strong>and</strong> common carp. Theseresults clearly demonstrated the beneficial effect <strong>of</strong> the Spirul<strong>in</strong>a diet on the yield <strong>and</strong>quality <strong>of</strong> carp fry.Dietary supplementation <strong>of</strong> Chlorella ellipsoidea powder at 2 percent on a dryweightb<strong>as</strong>is showed higher weight ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> improved <strong>feed</strong> efficiency <strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong>efficiency ratios <strong>in</strong> juvenile Japanese flounders (Paralichthys olivaceus); the addition <strong>of</strong>Chlorella had positive effects <strong>as</strong> it significantly reduced serum cholesterol <strong>and</strong> body fatlevels <strong>and</strong> also led to improved lipid metabolism (Kim et al., 2002).

Algae 15Clearly, no def<strong>in</strong>ite conclusions can be arrived at this stage about the value <strong>of</strong> us<strong>in</strong>gmacro<strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong> major dietary <strong>in</strong>gredients or prote<strong>in</strong> sources <strong>in</strong> aqua<strong>feed</strong>s. Moderategrowth responses <strong>and</strong> good food utilization (FCR 1.5–2.0) were generally recordedwhen dried algal meal were used <strong>as</strong> a partial replacement <strong>of</strong> fishmeal prote<strong>in</strong>. However,the collection, dry<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> pelletization <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> require considerable time <strong>and</strong> effort.Furthermore, cultivation costs would have to be taken <strong>in</strong>to consideration. Therefore,further cost-benefit on-farm trials that take these costs <strong>in</strong>to consideration are neededbefore any def<strong>in</strong>ite conclusions on the future application <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong> fish <strong>feed</strong> can bedrawn.1.5.2 Algae <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> additivesThe ma<strong>in</strong> applications <strong>of</strong> micro<strong>algae</strong> for aquaculture are <strong>as</strong>sociated with nutrition,be<strong>in</strong>g used fresh (<strong>as</strong> sole component or <strong>as</strong> food additive to b<strong>as</strong>ic nutrients) forcolour<strong>in</strong>g the flesh <strong>of</strong> salmonids <strong>and</strong> for <strong>in</strong>duc<strong>in</strong>g other biological activities (Muller-Feuga, 2004). Several <strong>in</strong>vestigations have been carried out on the use <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong> additives<strong>in</strong> fish <strong>feed</strong>. Feed<strong>in</strong>g trials were carried out with many fish species, most commonlyred sea bream (Pagrus major), ayu (Plecoglossus altivelis), nibbler (Girella punctata),striped jack (Pseudoceranx dentex), cherry salmon (Oncorhynchus m<strong>as</strong>ou), yellowtail(Seriola qu<strong>in</strong>queradiata), black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegeli), ra<strong>in</strong>bow trout(Oncorhynchus mykiss), rockfish (Seb<strong>as</strong>tes schlegeli) <strong>and</strong> Japanese flounder (Paralichthysolivaceus). Various types <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> were used; the most extensively studied ones have beenthe blue-green <strong>algae</strong> Spirul<strong>in</strong>a <strong>and</strong> Chlorella; the brown <strong>algae</strong> Ascophyllum, Lam<strong>in</strong>aria<strong>and</strong> Undaria; the red alga Porphyra; <strong>and</strong> the green alga Ulva. Fagbenro (1990) predictedthat the <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> cellul<strong>as</strong>e activity could be responsible for the capacity <strong>of</strong> thecatfish Clari<strong>as</strong> isherencies to digest large quantities <strong>of</strong> Cyanophyceae.A summary <strong>of</strong> the results <strong>of</strong> selected <strong>feed</strong><strong>in</strong>g trials with <strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> additives ispresented <strong>in</strong> Table 1.3. Most <strong>of</strong> these research studies were conducted <strong>in</strong> Japan withJapanese fish species, although the results may well be applicable to other species <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong> other countries.Table 1.3 shows that dried algal meals or their extracts have been added to test fish dietsat levels up to 21 percent level. The responses <strong>of</strong> test fish fed <strong>algae</strong> supplemented dietswere compared with fish fed st<strong>and</strong>ard control diets. Although various types <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong>fish species were used <strong>in</strong> these evaluations, not all <strong>algae</strong> were evaluated <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> additivesfor every different species. As the ma<strong>in</strong> biochemical constituents <strong>and</strong> digestibility aredifferent among <strong>algae</strong>, the effect <strong>of</strong> dietary <strong>algae</strong> varies with the <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> fish species(Mustafa <strong>and</strong> Nakagawa, 1995). While study<strong>in</strong>g the effect <strong>of</strong> two seaweeds (Undariap<strong>in</strong>natifida <strong>and</strong> Ascophyllum nodosum) at different supplementation levels for red seabream, Yone, Furuichi <strong>and</strong> Urano (1986a) observed best growth <strong>and</strong> <strong>feed</strong> efficiency froma diet conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 5 percent U. p<strong>in</strong>natifida followed by a diet conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 5 percent A.nodosum. Similarly, Mustafa et al. (1994b) observed more pronounced effects on growth<strong>and</strong> <strong>feed</strong> utilization <strong>of</strong> red sea bream by <strong>feed</strong><strong>in</strong>g a diet conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Spirul<strong>in</strong>a comparedto one conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Ascophyllum. In another study, Mustafa et al. (1995) studied thecomparative efficacy <strong>of</strong> three different <strong>algae</strong> (Ascophyllum nodosum, Porphyra yezoensis<strong>and</strong> Ulva pertusa) for red sea bream <strong>and</strong> noted that <strong>feed</strong><strong>in</strong>g Porphyra showed the mostpronounced effects on growth <strong>and</strong> energy accumulation, followed by Ascophyllum <strong>and</strong>Ulva. However, research results obta<strong>in</strong>ed so far do not specifically identify any specific<strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong> the most suitable <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> additives for any particular fish species.Nevertheless, the results <strong>of</strong> various research studies show that <strong>algae</strong> <strong>as</strong> dietaryadditives contribute to an <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>e <strong>in</strong> growth <strong>and</strong> <strong>feed</strong> utilization <strong>of</strong> cultured fish dueto efficacious <strong>as</strong>similation <strong>of</strong> dietary prote<strong>in</strong>, improvement <strong>in</strong> physiological activity,stress response, starvation tolerance, dise<strong>as</strong>e resistance <strong>and</strong> carc<strong>as</strong>s quality. In fish fed<strong>algae</strong>-supplemented diets, accumulation <strong>of</strong> lipid reserves w<strong>as</strong> generally well controlled<strong>and</strong> the reserved lipids were mobilized to energy prior to muscle prote<strong>in</strong> degradation

16<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquaculture – A review<strong>in</strong> response to energy requirements. In complete pelleted diets, algal supplementation<strong>of</strong> 5 percent or less w<strong>as</strong> found to be adequate.Spirul<strong>in</strong>a are widely used <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> additives <strong>in</strong> the Japanese fish farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dustry.Henson (1990) reported that Spirul<strong>in</strong>a improved the performances <strong>of</strong> ayu, cherrysalmon, sea bream, mackerel, yellowtail <strong>and</strong> koi carp. The levels <strong>of</strong> supplementationused by Japanese farmers are 0.5-2.5 percent. Henson (1990) further reported thatJapanese fish farmers used about US$2.5 million worth <strong>of</strong> Spirul<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> 1989. Fiveimportant benefits reported by us<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>feed</strong> conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g this alga were improvedgrowth rates; improved carc<strong>as</strong>s quality <strong>and</strong> colouration; higher survival rates; reducedrequirement for medication; <strong>and</strong> reduced w<strong>as</strong>tes <strong>in</strong> effluents. However, the high cost<strong>of</strong> most <strong>of</strong> these <strong>algae</strong> may limit their use to the commercial production <strong>of</strong> high valuefish only.

172. Float<strong>in</strong>g <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong>– AzollaFloat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> are def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>as</strong> plants that float on the water surface,usually with submerged roots. Float<strong>in</strong>g species are generally not dependent on soil orwater depth.Azolla spp. are heterosporous free-float<strong>in</strong>g freshwater ferns that live symbioticallywith Anabaena azollae, a nitrogen-fix<strong>in</strong>g blue-green <strong>algae</strong>. These plants have been<strong>of</strong> particular <strong>in</strong>terest to botanists <strong>and</strong> Asian agronomists because <strong>of</strong> their <strong>as</strong>sociationwith blue-green <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> their rapid growth <strong>in</strong> nitrogen deficient habitats (Islam <strong>and</strong>Haque, 1986). The genus Azolla <strong>in</strong>cludes six species distributed widely throughouttemperate, sub-tropical <strong>and</strong> tropical regions <strong>of</strong> the world. It is not clear whether thesymbiont is the same <strong>in</strong> the various Azolla species.Azolla spp. consists <strong>of</strong> a ma<strong>in</strong> stem grow<strong>in</strong>g at the surface <strong>of</strong> the water, withalternate leaves <strong>and</strong> adventitious roots at regular <strong>in</strong>tervals along the stem. Secondarystems develop at the axil <strong>of</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> leaves. Azolla fronds are triangular or polygonal <strong>and</strong>float on the water surface <strong>in</strong>dividually or <strong>in</strong> mats. At first glance, their gross appearanceis little like what are conventionally thought <strong>of</strong> <strong>as</strong> ferns; <strong>in</strong>deed, one common name forthem is duckweed ferns. Plant diameter ranges from 1/3 to 1 <strong>in</strong>ch (1-2.5 cm) for <strong>small</strong>species like Azolla p<strong>in</strong>nata to 6 <strong>in</strong>ches (15 cm) or more for A. nilotica (Ferent<strong>in</strong>os,Smith <strong>and</strong> Valenzuela, 2002).2.1 Cl<strong>as</strong>sificationThe genus Azolla belongs to the s<strong>in</strong>gle genus family Azollaceae. The six recognizablespecies with<strong>in</strong> the genus are grouped under two subgenera: Euazolla <strong>and</strong>Rhizosperma.The four species under the sub-genus Euazolla are A. filiculoides, A. carol<strong>in</strong>iana,A. mexicana <strong>and</strong> A. microphylla. It is thought that these four species orig<strong>in</strong>ated fromtemperate, sub-tropical <strong>and</strong> tropical regions <strong>of</strong> North <strong>and</strong> South America (Van Hove,1989). However, Zimmerman et al. (1991) found three <strong>of</strong> these species (A. carol<strong>in</strong>iana,A. mexicana <strong>and</strong> A. microphylla) to have close taxonomic aff<strong>in</strong>ity <strong>and</strong> similar responsesto phosphorus deficiency <strong>and</strong> recommended that they be considered <strong>as</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>glespecies.The two species under sub-genus Rhizosperma are A. nilotica <strong>and</strong> A. p<strong>in</strong>nata. A.nilotica is a native <strong>of</strong> E<strong>as</strong>t Africa <strong>and</strong> can be found from Sudan to Mozambique (VanHove, 1989). A. p<strong>in</strong>nata h<strong>as</strong> two different varieties that vary <strong>in</strong> their distributionpatterns. A. p<strong>in</strong>nata var. imbricata orig<strong>in</strong>ates from subtropical <strong>and</strong> tropical Asia whileA. p<strong>in</strong>nata var. p<strong>in</strong>nata occurs <strong>in</strong> Africa <strong>and</strong> is known <strong>as</strong> African stra<strong>in</strong>.2.2 Characteristics2.2.1 ImportanceBecause Azolla h<strong>as</strong> a higher crude prote<strong>in</strong> content (rang<strong>in</strong>g from 19 to 30 percent)than most green forage crops <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>and</strong> a rather favourableessential am<strong>in</strong>o acid (EAA) composition for animal nutrition (rich <strong>in</strong> lys<strong>in</strong>e), it h<strong>as</strong>also attracted the attention <strong>of</strong> livestock, poultry <strong>and</strong> fish farmers (Cagauan <strong>and</strong> Pull<strong>in</strong>,1991). In Asia Azolla h<strong>as</strong> been long used <strong>as</strong> green manure for crop production <strong>and</strong>a supplement to diets for pigs <strong>and</strong> poultry. Some stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> Azolla can fix <strong>as</strong> much<strong>as</strong> 2-3 kg <strong>of</strong> nitrogen/ha/day. Azolla doubles its biom<strong>as</strong>s <strong>in</strong> 3-10 days, depend<strong>in</strong>g

18<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquaculture – A reviewon conditions, <strong>and</strong> e<strong>as</strong>ily reaches a st<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g crop <strong>of</strong> 8-10 tonnes/ha fresh weight <strong>in</strong>Asian rice fields; 37.8 tonnes/ha fresh weight (2.78 tonnes/ha dry weight) h<strong>as</strong> beenreported for A. p<strong>in</strong>nata <strong>in</strong> India (Pull<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Almazan, 1983). Recently, Liu et al. (2008)have reported the application <strong>of</strong> Azolla <strong>as</strong> a controlled ecological life support system(CELSS) for its strong photosynthetic oxygen-rele<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>g capacity. Azolla provides aprotected environment <strong>and</strong> a fixed source <strong>of</strong> carbon to the blue-green filamentous <strong>algae</strong>Anabaena spp. (Wagner, 1997).2.2.2 Environmental requirementsThe potential for rear<strong>in</strong>g Azolla is restricted by climatic factors, water <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>oculumavailability, the <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> pests, phosphorus requirements <strong>and</strong> the need forlabour <strong>in</strong>tensive management (Cagauan <strong>and</strong> Pull<strong>in</strong>, 1991). Water is the fundamentalrequirement for the growth <strong>and</strong> multiplication <strong>of</strong> Azolla. The plant is extremelysensitive to lack <strong>of</strong> water. Although Azolla can grow on wet mud surfaces or wet pitlitters, it prefers grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a free-float<strong>in</strong>g state (Beck<strong>in</strong>g, 1979). A strip <strong>of</strong> water notmore than a few centimetres deep favours growth because it provides good m<strong>in</strong>eralnutrition, with the roots not too far from the soil, <strong>and</strong> also because it reduces w<strong>in</strong>deffects (Van Hove, 1989). Strong w<strong>in</strong>ds can accumulate Azolla to one side <strong>of</strong> the stretch<strong>of</strong> water, creat<strong>in</strong>g an overcrowded condition <strong>and</strong> thus slow<strong>in</strong>g growth.Azolla can survive a water pH rang<strong>in</strong>g from 3.5-10, reported optimum growthoccurr<strong>in</strong>g at pH 4.5-7.0. Watanabe et al. (1977) reported that the growth <strong>of</strong> Azolla w<strong>as</strong>optimum at pH 5.5 <strong>and</strong> <strong>FAO</strong> (1977) recorded that soils <strong>of</strong> pH 6 to 7 support the bestgrowth.Sal<strong>in</strong>ity tolerance <strong>of</strong> Azolla species also varies. The growth rate <strong>of</strong> A. p<strong>in</strong>natadecl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>as</strong> its sal<strong>in</strong>ity <strong>in</strong>cre<strong>as</strong>es above 380 mg/l (Thuyet <strong>and</strong> Tuan, 1973). Accord<strong>in</strong>gto Reddy et al. (2005) Azolla can withst<strong>and</strong> sal<strong>in</strong>ity <strong>of</strong> up to 10 ppt but Haller, Sutton<strong>and</strong> Burlowe (1974) reported that the growth <strong>of</strong> A. carol<strong>in</strong>iana ce<strong>as</strong>es at about 1.3 ppt<strong>and</strong> higher concentrations result <strong>in</strong> death. A. filiculoides h<strong>as</strong> been reported to be mostsalt-tolerant (I. Watanabe pers. comm., cited by Cagauan <strong>and</strong> Pull<strong>in</strong>, 1991).Azolla grows <strong>in</strong> full to partial shade (100-50 percent sunlight) with growthdecre<strong>as</strong><strong>in</strong>g quickly under heavy shade (Ferent<strong>in</strong>os et al., 2002). Generally, Azollarequires 25-50 percent full sunlight for its normal growth; slight shade is <strong>of</strong> benefitto its growth <strong>in</strong> field conditions. The biom<strong>as</strong>s production greatly decre<strong>as</strong>es at a light<strong>in</strong>tensity lower than 1 500 lux (Liu et al., 2008).Like all other plants, Azolla needs all the macro- <strong>and</strong> micro-nutrients for its normalgrowth <strong>and</strong> vegetative multiplication. All elements are essential; phosphorus is <strong>of</strong>tenthe most limit<strong>in</strong>g element for its growth. For normal growth, 0.06 mg/l/day is required.This level can be achieved <strong>in</strong> field conditions by the split application <strong>of</strong> superphosphateat 10-15 kg/ha (Sherief <strong>and</strong> James, 1994). 20 mg/l is the optimum concentration(Ferent<strong>in</strong>os et al., 2002). The symptoms <strong>of</strong> phosphorous deficiency are red-colouredfronds (due the presence <strong>of</strong> the pigment anthocyan<strong>in</strong>), decre<strong>as</strong>ed growth <strong>and</strong> curledroots. Macronutrients such <strong>as</strong> P, K, Ca <strong>and</strong> Mg <strong>and</strong> micronutrients such <strong>as</strong> Fe, Mo <strong>and</strong>Co have been shown to be essential for the growth <strong>and</strong> nitrogen fixation <strong>of</strong> Azolla(Khan <strong>and</strong> Haque, 1991).The temperature tolerance <strong>of</strong> Azolla varies widely between its species <strong>and</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>s. Ingeneral, Azolla h<strong>as</strong> low tolerance to high temperature <strong>and</strong> that restricts its use <strong>in</strong> tropicalagriculture. There are, however, stra<strong>in</strong>s that can adapt successfully to high temperature.Cagauan <strong>and</strong> Pull<strong>in</strong> (1991) ranked different Azolla species from the most to the le<strong>as</strong>theat-tolerant, b<strong>as</strong>ed on the optimum temperature for good growth: A. mexicana > A.p<strong>in</strong>nata var. p<strong>in</strong>nata > A. microphylla > A. p<strong>in</strong>nata var. imbricata, A. carol<strong>in</strong>iana > A.filiculoides (Table 2.1). In general, the optimum temperature for growth <strong>of</strong> all Azoll<strong>as</strong>pecies is around 25 ºC, except that <strong>of</strong> A. mexicana, whose optimum temperature is

Float<strong>in</strong>g <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> – Azolla 19Table 2.1Temperature tolerance <strong>of</strong> five species <strong>of</strong> AzollaSubgenera Species Water temperature (ºC)M<strong>in</strong>imum Maximum Optimum for growthEuazolla A. filiculoides 0-10 38-42 20-25A. carol<strong>in</strong>iana

20<strong>Use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>algae</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>aquatic</strong> <strong>macrophytes</strong> <strong>as</strong> <strong>feed</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>small</strong>-<strong>scale</strong> aquaculture – A reviewTable 2.2Chemical analyses <strong>of</strong> various Azolla speciesAzolla species Moisture(percent)Composition 1(percent DM 1 )M<strong>in</strong>erals(percent DM)ReferenceCP EE CF Ash CC Ca P KA. filiculoides 93.5 2 25.0-28.5 3.1 n.s. 17.3 4.4-11.5 0.5-1.5 1.0-1.5 6.0 modified from Cagauan <strong>and</strong>Pull<strong>in</strong> (1991)A. carol<strong>in</strong>iana 20.6-22.6 n.s. n.s. n.s. 8.5 0.6 1.3 5.3 modified from Cagauan <strong>and</strong>Pull<strong>in</strong> (1991)A. p<strong>in</strong>nata var. imbricate 26.0 n.s. n.s. n.s. 4.1 0.4 1.3 4.5 modified from Cagauan <strong>and</strong>Pull<strong>in</strong> (1991)A. p<strong>in</strong>nata (tank culture) 18.2 1.3 n.s. 21.7 n.s. 1.6 0.6 n.s. modified from Cagauan <strong>and</strong>Pull<strong>in</strong> (1991)A. p<strong>in</strong>nata (field culture) 22.2 2.9 n.s. 18.3 14.7 n.s. n.s. n.s. modified from Cagauan <strong>and</strong>Pull<strong>in</strong> (1991)A. p<strong>in</strong>nata 21.4 2.7 12.7 16.2 Alalade <strong>and</strong> Iyayi (2006)A. microphylla (lab. culture) 21.8 2.9 n.s. 21.6 15.6 n.s. n.s. n.s. modified from Cagauan <strong>and</strong>Pull<strong>in</strong> (1991)A. microphylla (field culture) 20.0-26.0 3.0-3.5 n.s. 14-15 4.0-14.0 0.7 1.6 5.5 modified from Cagauan <strong>and</strong>Pull<strong>in</strong> (1991)A. microphylla hybrid (field culture) 19.0 4.0-4.5 n.s. 16.0-17.0 2.5-3.0 n.s. n.s. n.s. modified from Cagauan <strong>and</strong>Pull<strong>in</strong> (1991)Various Azolla spp. 13.0-30.0 4.4-6.3 n.s. 9.7-23.8 5.6-15.2 0.2-0.7 0.1-1.6 0.3-6.0 Reddy et al. (2005)Azolla sp. n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. n.s. 1.0 0.4 2.5 Ferent<strong>in</strong>os, Smith <strong>and</strong> Valenzuela,(2002)1CP = crude prote<strong>in</strong>; EE = ether extract; CC = crude cellulose; Ca = calcium; P = phosphorus; K = pot<strong>as</strong>sium2Data obta<strong>in</strong>ed from Tacon (1987)