The AAO Journal - American Academy of Osteopathy

The AAO Journal - American Academy of Osteopathy

The AAO Journal - American Academy of Osteopathy

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong>Forum for Osteopathic ThoughtJOURNALOfficial Publication <strong>of</strong> the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong>Tradition Shapes the Future Volume 22 Number 2 Summer 2012Special July 4 th Issue onMilitary Matters

<strong>The</strong> <strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong> is your voice . . ....in teaching, advocating, and researching the science, art and philosophy <strong>of</strong> osteopathic medicine, emphasizing theintegration <strong>of</strong> osteopathic principles, practices and manipulative treatment in patient care.<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> Membership Committee invites you to join the<strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong> as a 2012-2013 member.<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> is your pr<strong>of</strong>essional organization. It fosters thecore principles that led you to choose to become a Doctor <strong>of</strong><strong>Osteopathy</strong>.For just $5.01 a week (less than a large specialty c<strong>of</strong>fee at yourfavorite c<strong>of</strong>fee shop) or just 71 cents a day (less than a bottle <strong>of</strong>water), you can become a member <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>of</strong>essional specialtyorganization dedicated to the core principles <strong>of</strong> your pr<strong>of</strong>ession!Your membership dues provide you with:• A national advocate for osteopathic manipulative medicine(including appropriate reimbursement for OMM services)with osteopathic and allopathic pr<strong>of</strong>essionals, public policymakers, the media and the public.• Referrals <strong>of</strong> patients through the Search for a Physician toolon the <strong>AAO</strong> website, as well as calls to the <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>of</strong>fice.• Discounts on quality educational programs provided by <strong>AAO</strong>at its annual convocation and weekend workshops.• New online courses.• Networking opportunities with your peers.• Discounts on publications in the <strong>AAO</strong> Bookstore.• Free subscription to the <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> publishedelectronically four times annually.• Free subscription to the online <strong>AAO</strong> Member Newsletter.• Access to the members only section <strong>of</strong> the <strong>AAO</strong> website,which will be enhanced in the coming months to include newfeatures such as resource links, a job bank, and much more.• Discounts in advertising in <strong>AAO</strong> publications, on the Website and at the <strong>AAO</strong>’s Convocation.• Access to the <strong>American</strong> Osteopathic Board <strong>of</strong>Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine—the only certifying boardin manual medicine that exists in the medical world today.• Maintenance <strong>of</strong> an earned Fellowship program to recognizeexcellence in the practice <strong>of</strong> osteopathic manipulativemedicine.• Promotion <strong>of</strong> research on the efficacy <strong>of</strong> osteopathicmedicine.• Support for the future <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>of</strong>ession through the Student<strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong> on osteopathic medicalschool campuses.• Your pr<strong>of</strong>essional dues are deductible as a business expense.If you have any questions regarding membership or renewalmembership, please contact Susan Lightle at (317) 879-1881 orslightle@academy<strong>of</strong>osteopathy.org. Thank you for supporting the<strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong>.Founding Chair <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine<strong>The</strong> proposed Campbell University School <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Medicine (CUSOM) is currently in the accreditation review process, with anticipatedmatriculation in August 2013.<strong>The</strong> Chair <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine (OMM) is responsible for OMM program development, including participation in designing theOMM curriculum, as well as assisting the Associate Dean for Biomedical Affairs and Associate Dean for Clinical Affairs with development <strong>of</strong> the preclinicaland clinical curriculum. This role includes faculty recruitment and faculty development to ensure curriculum is successfully delivered to theCUSOM students. Other responsibilities include the supervision <strong>of</strong> the school’s OMM faculty and students to advance the student’s pr<strong>of</strong>essionalism,knowledge, skills, and competencies to the level required for a graduate Osteopathic physician.This is a wonderful opportunity to help develop a creative, vibrant, student-centered learning community in a faith-based environment. Applicantsmust be AOA board-certified through the <strong>American</strong> Osteopathic Board <strong>of</strong> Neuromusculoskeletal Medicine or have received a Certifi cate <strong>of</strong> SpecialPr<strong>of</strong>i ciency in Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine (C-SPOMM). Candidates with previous academic experience will be given preference. All <strong>of</strong>fersare subject to background checks and reference reviews.Send CV, letter <strong>of</strong> application, and three references electronically to:Brian Kessler, DOAssociate Dean for Clinical Affairscusomemployment@campbell.eduCUSOM is committed to affirmative action, equal opportunity and the diversity <strong>of</strong> its workforce.www.campbell.edu/cusomPage 2<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Volume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012

THE <strong>AAO</strong> FORUM FOR OSTEOPATHIC THOUGHTOURNALOfficial Publication <strong>of</strong> the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong>J3500 DePauw Boulevard, Suite 1080Indianapolis, IN 46268Phone: (317) 879-1881Fax: (317) 879-0563www.academy<strong>of</strong>osteopathy.org<strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong>Jane E. Carreiro, DO..................................................................PresidentDavid C<strong>of</strong>fey, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>................................................ President-ElectDiana L. Finley, CMP................................................ Executive DirectorEditorial Advisory BoardMurray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPHDenise K. Burns, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>Eric J. Dolgin, DOClaire M. Galin, DOWilliam J. Garrity, DOStephen I. Goldman, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>Stefan L. J. Hagopian, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>Raymond J. Hruby, DO, MS, F<strong>AAO</strong>Brian E. Kaufman, DOHollis H. King, DO, PhD, F<strong>AAO</strong>Paul R. Rennie, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>Hallie J. Robbins, DOMark E. Rosen, DO<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>Murray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPH.....................Scientific EditorDiana Finley, CMP.......................................................Supervising EditorTessa Boeing....................................................................Managing Editor<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> is the <strong>of</strong>ficial publication <strong>of</strong> the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong>. Issues are published in March, June, September, andDecember each year.<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> is not responsible for statements made by anycontributor. Although all advertising is expected to conform to ethicalmedical standards, acceptance does not imply endorsement by thisjournal.Opinions expressed in <strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> are those <strong>of</strong> authors or speakersand do not necessarily reflect viewpoints <strong>of</strong> the editors or <strong>of</strong>ficial policy<strong>of</strong> the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong> or the institutions with whichthe authors are affiliated, unless specified.Please send address/e-mail address changes to:slightle@academy<strong>of</strong>osteopathy.orgDisclaimer: Dr. Berkowitz was not involved in the editorial decisionto publish the articles he co-authored, which was left up to the editorialcommittee <strong>of</strong> the journal.Correction: In the article “Manipulative Methods <strong>of</strong> Dr. Still” byJamie Archer, DO (UK), from the December issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>,the quote from Dr. Edwards in the fifth paragraph <strong>of</strong> page 20 wasmisattributed to Dr. Still. On page 23, the following sentence wasomitted in reference to Figures 4 and 5: According to the dictionarythe very word “swinging” refers to an oscillating, rotary or repetitivemovement. Finally, “Figure 8: Hip Treatment” should have been labeled“Figure 9: Hip treatment.” <strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> apologizes for these errors.Advertising rates for <strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> are listed to the right. Please callTessa Boeing at (317) 879-1881 for more information.Subscriptions: $60.00 per yearTRADITION SHAPES THE FUTURE • VOLUME 22 NUMBER 2 • SUMMER 2012<strong>The</strong> mission <strong>of</strong> the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong> is to teach, advocateand research the science, art and philosophy <strong>of</strong> osteopathic medicine,emphasizing the integration <strong>of</strong> osteopathic principles, practices andmanipulative treatment in patient care.In this Issue:<strong>AAO</strong> Calendar <strong>of</strong> Events.......................................................................................7CME Certification <strong>of</strong> Home Study Form............................................................48Component Society Calendar <strong>of</strong> Events..............................................................64Regular Features:View from the Pyramids: A resource journal on traumatic brain injury and posttraumaticstress disorder in veterans......................................................................4Murray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS MPHFrom the Archives...............................................................................................60Editorial:“<strong>The</strong> difference a DO makes” in welcoming home our troops.............................8William Bograkas, DO, MA, FACOEP, COL, MC, FS USA (retired)Original Contributions:Understanding blast-induced traumatic brain injury (bTBI) through mechanismsand patterns <strong>of</strong> injury...........................................................................................10Patrick M. Malie, MS, OMS III; Marc Quentin Sonnier, Jr., MS;Murray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPHClinical management and multipotential treatment strategies for blast-inducedtraumatic brain injury (bTBI)..............................................................................18Patrick M. Malie, MS, OMS III; Murray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPHBlast-induced mTBI as etiology <strong>of</strong> post-traumatic stress disorder in militaryveterans ...............................................................................................................25Marc Quentin Sonnier, Jr., MS; Murray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPHSociodemographic analysis <strong>of</strong> psychiatric emergency services in a state withgreater than average veteran density....................................................................36Livia Cara, MS; Murray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPHHolistic osteopathic approach to the care <strong>of</strong> veterans with post-traumatic stressdisorder: Case report...........................................................................................43Andrew Lovy, DO, FACN, DMOR; Murray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPHBiomarkers and neoroimaging techniques to detect blast-induced traumatic braininjury (bTBI).......................................................................................................49Patrick M. Malie, MS, OMS III; Murray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPH<strong>The</strong> safety and efficacy <strong>of</strong> osteopathic manipulation in the treatment <strong>of</strong> mildtraumatic brain injury (mTBI) in U.S. service members as validated by SPECTscan: A report <strong>of</strong> planned research.......................................................................54Natalie A. Nevins, DO, MSHPE; Marcel Fraix, DO, FAAPMRAdvertising RatesPlaced 1 time Placed 2 times Placed 4 timesFull Page 7.5” x 10” $600 $575 $550Half Page 7.5” x 5” $400 $375 $350Third Page 7.5” x 3.3” $300 $275 $200Fourth Page 3.75” x 5” $200 $175 $150Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Card 3.5” x 2” $60Classified$1.00 per wordVolume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012 <strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Page 3

View From the PyramidsA resource journal on traumatic brain injury andpost-traumatic stress disorder in veteransMurray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPHAs part <strong>of</strong> the 2011 White House Joining ForcesInitiative aimed at taking action to better serve America’smilitary families, the <strong>American</strong> Association <strong>of</strong> Colleges<strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM) looked at the mannerin which the curricula taught at the nation’s osteopathicmedical colleges provide instruction in military-relatedmedical issues. An analysis <strong>of</strong> the complete curriculataught at these schools was performed. When the AACOMeffort was first announced in December 2011, this Editorsought to provide a special, themed issue <strong>of</strong> the <strong>AAO</strong><strong>Journal</strong> that would emphasize the problems <strong>of</strong> traumaticbrain injury (TBI) and post-traumatic stress disorder(PTSD) in our veterans to coincide with the January 11public announcement <strong>of</strong> the Joining Forces Initiative. Fora number <strong>of</strong> reasons, this could not be accomplished inthe very short time that was available. Our colleagues atthe <strong>American</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Family Physicians(ACOFP), however, were able to publish a special, themedissue <strong>of</strong> the Osteopathic Family Physician in March 2012.My congratulations to Jay Shubrook, DO, Editor, andMeredith Norris, DO, Associate Editor.This month’s special, themed issue is the first for the<strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong> and its <strong>Journal</strong>. Specificcontent includes, but is not limited to, post-traumatic stressdisorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury (TBI), depressionand psychosocial issues related to military culture andfamilies. It was envisioned that this issue may serve as aresource for physicians, especially non-veteran civilianphysicians, who must be aware <strong>of</strong> how veterans can slipthrough the cracks <strong>of</strong> the Veterans Affairs system and haveissues tied to their military service.Our Guest Editor, Dr. William Bograkos, received hisDisaster and Chemical, Biological, Radiologic, Nuclearand Explosive (CBRNE) training during his 28 years <strong>of</strong>military service. He is a retired Colonel in the U.S. ArmyMedical Corps, and has served both the Army and the U.S.Air Force as a military Flight Surgeon and Family Practiceand Emergency Medicine Physician. Dr. Bograkos servedwith a Special Operations Weapons <strong>of</strong> Mass DestructionDetachment prior to, and during, the millennium. Heserved in the Balkans as a Division Surgeon and NATOMulti-National Peacekeeper from September 2001 to April2002. Dr. Bograkos chaired the U.S. Special OperationsCommand’s Curriculum Examination Board for theAdvanced Tactical Practitioner (SOF EMT-P) from 2004 to2006. He served the Pentagon’s Civil Military EmergencyPreparedness <strong>of</strong>fice as a Bioterrorism/Medical Consultantfor the Black Sea Initiative, and briefed at the First InterpolGlobal Conference on Preventing Bioterrorism in Lyon,France, in 2005.Of the contributing authors, several are veterans.Andrew Lovy, DO, FACN, DMOR, was the second DO tobe commissioned into the U.S. Army Medical Corps. Dr.Lovy served in Vietnam with the 506 th Infantry Regimentas part <strong>of</strong> the famed 101 st Airborne Division (“ScreamingEagles”). During World War II, the 506 th jumped intoFrance in the opening hours <strong>of</strong> D-Day, and fought their wayout <strong>of</strong> Bastogne during the Battle <strong>of</strong> the Bulge. Dr. Lovytook part in the 1968 Tet Offensive. For those not familiarwith the DMOR (Distinguished Member <strong>of</strong> the Regiment)designation, it is a special award conferred by theDepartment <strong>of</strong> the Army and sanctioned by the unit. Sincethe inception <strong>of</strong> the 506 th , approximately 40,000 troopshave been in the unit, and 112 have been so awarded. Untilthis year, Dr. Lovy was the only physician so awarded, and<strong>of</strong> the four medics who have since received the award, threeserved with him in Vietnam. This award is special becauseit is given by one’s peers to acknowledge service <strong>of</strong> thehighest magnitude.Murray R. Berkowitz, DO MA, MS, MPH, servedon active military duty as a Medical Corps Officer in theUnited States Army. Before attending medical school, Dr.Berkowitz served in numerous assignments in the U.S.Army and U.S .Air Force (USAF). He ultimately received aDirect Commission in the U.S. Army as an Armor/CavalryOfficer and served assignments as an Officer CandidatePage 4<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Volume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012

School (OCS) Instructor/Tactical Officer, TransportationOfficer, Chemical Officer and Infantry CompanyCommander with the Army, the Reserve, and the NationalGuard. He transferred to the USAF in January 1981. HisAir Force assignments included service with the StrategicAir Command, Military Airlift Command, DefenseCommunications Agency, USAF Headquarters (Pentagon)and the Office <strong>of</strong> the Secretary <strong>of</strong> Defense (OSD). Heserved for more than seven years in the space program,including assignments as Staff Development EngineeringManager for the space shuttle, Space Launch and ControlDivision; Directorate <strong>of</strong> Space Systems and Command,Control, Communications; Deputy Chief <strong>of</strong> Staff/Researchin the Department <strong>of</strong> Development and Acquisition at theUSAF Headquarters; Airborne Space Command, Control,Communications Flight Test Engineering Manager at theOSD; with attachment to the 89 th Military Airlift Wing(Special Air Missions/Presidential Support) at AndrewsAFB in Maryland; and as the Special Assistant for Spaceand Command, Control, Communications to the ChiefScientist <strong>of</strong> the Air Force. During the first Gulf War, Dr.Berkowitz served as a Special Assistant to the Director<strong>of</strong> Plans; Directorate <strong>of</strong> Plans; and following cessation <strong>of</strong>hostilities, Chief <strong>of</strong> Research Services for the Secretary’sGulf War Study. Dr. Berkowitz is a disabled veteran,medically separated from the military due to service-relateddisabilities. A former “Line <strong>of</strong> the Air Force” LieutenantColonel, he was a military aviator and parachutist, andalso holds the Master Space Badge and the Office <strong>of</strong> theSecretary <strong>of</strong> Defense Identification Badge. He has received26 military awards and decorations.Natalie A. Nevins, DO, MSHPE, is a former Majorin the United States Air Force Medical Corps. Dr. Nevinswas assigned to the 61 st Medical Squadron at Los AngelesAir Force Base as a Family Practice Physician, where sheheld positions as Chief <strong>of</strong> Medical Field Response; ClinicalDirector for Laboratory Services; Chairman <strong>of</strong> the InfectionControl Department; and Director <strong>of</strong> Radiology Services.She lectures for the California Preparedness and EducationNetwork on issues related to Disaster Preparedness,Bioterrorism, Chemical and Radiological Warfare andEmerging Infectious Diseases.Finally, I would like to gratefully acknowledge themany editing and other contributions <strong>of</strong> Ms. Tessa Boeing.Without her continuing efforts, this special issue <strong>of</strong> the<strong>Journal</strong> would have been delayed.Imagine expandingwhat you know every year.Chair, Department <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine (OMM)Reporting directly to the Dean <strong>of</strong> the School and working closely with the Dean’s Cabinet, this extraordinary leader will guide the Department <strong>of</strong> OsteopathicManipulative Medicine toward excellence in teaching, research, patient care, administrative services and community activities. Yours will be a highly versatile role,encompassing everything from transforming our mission and vision into reality through coaching and mentoring, and creating an environment <strong>of</strong> cooperationand trust, to serving as spokesperson for the School, and directing the recruitment and retention <strong>of</strong> the highest quality faculty and staff. In addition, you will beresponsible for developing and managing the budget, creating effective work plans and conducting performance appraisals. You will also serve as the ProgramDirector for the Neuromuscular Medicine/Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine Plus One Residency Program. Crucial to your success will be your ability to identifythe needs <strong>of</strong> the University and School and take decisive action to meet them.<strong>The</strong> inspired candidate we seek must be a Doctor <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong> (DO) with board certification in NMM/OMM, including five years <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional experiencethat include academic experience. Proven accomplishment in clinical and educational programs and a commitment to stimulating research activities required.Must have the academic and pr<strong>of</strong>essional experience necessary to qualify at the rank <strong>of</strong> Pr<strong>of</strong>essor (preferred) or Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor and must be able to provideexamples <strong>of</strong> leadership (i.e. previous departmental leadership positions, involvement in regional/national organizations, etc.), teambuilding (i.e. previoussuccesses, experience, interpersonal skills), academic strength (i.e. teaching experience, research experience, publications), clinical strength (peer recognition,reputation, patient satisfaction) and management strength (coaching, type and quality <strong>of</strong> management experience, advanced degree with experience). Requires ademonstrated commitment to the values <strong>of</strong> osteopathy and continuous quality improvement, sound business acumen and a strong working knowledge <strong>of</strong> clinicalpractice in order to manage the OMM Department in a fiscally sound manner. NJ State medical license, DEA and CDS are required.Applicants should submit a letter <strong>of</strong> interest and curriculum vitae to: Vincent DeRisio, DO, AssociateDean for Clinical Affairs, c/o Ms. Tammy Merchant, UMDNJ-School <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Medicine, OneMedical Center Drive, Academic Center, Suite 305, Stratford, NJ 08084, E-mail: merchata@umdnj.edu.Electronic submissions are encouraged, although paper applications will also be accepted. UMDNJ is anAA/EOE, M/F/D/V.Volume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012 <strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Page 5<strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>6/1/2012

Osteopathic Considerations in Systemic Dysfunction:Common Clinical ProblemsJuly 20-22, 2012, at New York College <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Medicine (NYCOM)Course DescriptionThis course presents a practical, hands-on osteopathicmanipulative treatment (OMT) approach to everyday patientsystemic complaints—ranging from sinusitis to pneumonia,gastritis to irritable bowel syndrome and headache to angina.<strong>The</strong> program centers on designing rational osteopathic care thatintegrates the five osteopathic care models and can be deliveredin a clinically-effective, time-efficient manner.It will teach clinicians to seek regional and segmental diagnosticsomatic clues to enhance and speed differential diagnosis.Participants will learn to integrate Chapman’s reflexes, collateralabdominal ganglia, and segmental diagnosis <strong>of</strong> the entire spineand sacroiliac joint. In treatment, the course will center on skillsused to enhance homeostasis. Participants will master skillsincluding sphenopalatine ganglia technique; collateral gangliainhibition; spleen pump; my<strong>of</strong>ascial spray and stretch; ischialrectal fossa technique; mesenteric lifts; rib raising; lymph pumps;liver pump; diaphragm redoming; and direct and indirect OMTtechniques to remove somatic dysfunction in the cranial, cervical,thoracic, costal, lumbar and sacral regions.While a number <strong>of</strong> techniques will be taught, emphasis will beplaced on developing skills and strategies to speed diagnosisand recovery. Residents, residency trainers and directors <strong>of</strong>medical education will be accorded special tips for maximizingintegration <strong>of</strong> these skills and strategies into their specificprograms.FacultyHugh Ettlinger, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>, is a 1987 graduate <strong>of</strong> NYCOM, wherehe serves as an Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic ManipulativeMedicine (OMM) and director <strong>of</strong> the NYCOM/St. Barnabas NMM/OMT Residency Program.Michael Kuchera, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>, is a 1980 graduate <strong>of</strong> KirksvilleCollege <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Medicine. He currently directs the OMMResearch and Human Performance and Biomechanics Laboratoryat Philadelphia College <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Medicine. He is alsoclinical director <strong>of</strong> the Center for Chronic Disorders <strong>of</strong> Aging andsecretary-general <strong>of</strong> the International Federation <strong>of</strong> Manual/Musculoskeletal Medicine.CME20 hours <strong>of</strong> Category 1-A AOA CME credit is anticipated.Course LocationNYCOM at New York Institute <strong>of</strong> TechnologyNorthern BoulevardOld Westbury, NY 11568(516) 686-3747Course TimesFriday and Saturday: 8:00 am - 5:00 pm (lunch provided)Sunday: 8:00 am - 12:00 pm (lunch on your own)Travel ArrangementsCall Tina Callahan <strong>of</strong> Globally Yours Travel at (800) 274-5975.<strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong> Registration FormOsteopathic Considerations in Systemic Dysfunction...July 20-22, 2012 at NYCOMName: ___________________________________________ AOA#: _____________Nickname for Badge: __________________________________________________Street Address: __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________City: __________________________________ State: ________ Zip: ___________Phone: _______________________________ Fax: ____________________________E-mail: __________________________________________________________________By releasing your fax/e-mail, you have given the <strong>AAO</strong> permission tosend marketing information to your fax or e-mail.Billing Address (if different than above): ___________________________________________________________________________________________________Registration RatesOn or before 6/22/2012; After 6/22/2012<strong>AAO</strong> Member $ 680.00 $ 780.00<strong>AAO</strong> Non-Member $ 780.00 $ 880.00Student/Intern/Resident $ 580.00 $ 680.00<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> accepts check, Visa, Mastercard or Discover payments inU.S. dollarsCredit Card #: ________________________________________________________Cardholder’s Name: ___________________________________________________Expiration Date: _____________________ 3-digit CVV#________________I hereby authorize the <strong>AAO</strong> to charge the above credit card for thefull course registration amount.Signature: ___________________________________________________________Click here to view the <strong>AAO</strong>’s Cancellation and Refund PolicyPlease submit registration form and payment via mail to the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong>,3500 DePauw Blvd., Suite 1080, Indianapolis, IN 46268 or by fax to (317) 879-0563.Or register online at www.academy<strong>of</strong>osteopathy.orgPage 6<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Volume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012

<strong>AAO</strong> Calendar <strong>of</strong> Events 2012-2013Mark your calendar for these upcoming <strong>Academy</strong> meetings and educational courses.July 17July 17-19July 20-22July 20-22August 10-11August 10-11August 16September 7-8October 6October 7October 8-10October 25-27November 9November 10November 11Nov. 30-Dec. 2Jan. 18-20, 2013Feb. 1-2, 2013Mar. 17-19, 2013Mar. 18-19, 2013Mar. 18-19, 2013Mar. 20, 2013Mar. 20-24, 2013<strong>AAO</strong> Board <strong>of</strong> Trustees Meeting—AOA Headquarters, Chicago, ILAOA Board <strong>of</strong> Trustees Meeting—<strong>The</strong> Farimont Hotel, Chicago, ILAOA House <strong>of</strong> Delegates Meeting—<strong>The</strong> Farimont Hotel, Chicago, ILOsteopathic Considerations in Systemic Dysfunction: Common Clinical ProblemsHugh Ettlinger, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>; Michael Kuchera, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>—NYCOM, Old Westbury, NYEducation Committee Meeting—University Place Conference Center & Hotel, Indianapolis, INS<strong>AAO</strong> Council Meeting—University Place Conference Center & Hotel, Indianapolis, INMembership Committee Teleconference, 8:30 pm ESTUltrasound Guided Injections—Millicent K. Channell, DO; Sajid Surve, DOUMDNJSOM, Stratford, NJFine-Tuning Your HVLA (Pre-AOA Convention)John G. Hohner, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>—San Diego, CA<strong>AAO</strong> Board <strong>of</strong> Trustees Meeting—San Diego, CA<strong>AAO</strong> Program at the AOA Convention: Osteopathic Considerations for Head and Neck DisordersMillicent K. Channell, DO, Program Chair—San Diego, CAProlotherapy Weekend—Mark S. Cantieri, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>; George J. Pasquarello, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>UNECOM, Biddeford, MEAOBNMM Meeting—Wyndham Hotel West, Indianapolis, INAOBNMM Oral & Practical Exams—Wyndham Hotel West, Indianapolis, INAOBNMM Written Exam—Wyndham Hotel West, Indianapolis, INOscillatory & Energetically Integrated Osteopathic Medicine in a Contemporary SettingZachary J. Comeaux, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>—NSUCOM, Fort Lauderdale, FLOsteopathic Approach to Clinically Relevant My<strong>of</strong>ascial Trigger PointsMichael Kuchera, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>—AZCOM, Glendale, AZEducation Committee Meeting—Indianapolis, INPeripheral Nerve course (Pre-Convocation)—Kenneth J. Lossing, DO—Rosen Shingle Creek Resort,Orlando, FLPediatric ENT course (Pre-Convocation)—Program Chair TBD—Rosen Shingle Creek Resort,Orlando, FLOsteopathic Considerations in Systemic Dysfunction <strong>of</strong> the Geriatric Patient (Pre-Convocation)Drs. Kuchera and Ettlinger—Rosen Shingle Creek Resort, Orlando, FLCellular Biology and the Cellular Matrix (Pre-Convocation)–Frank H. Willard, PhDRosen Shingle Creek Resort, Orlando, FL<strong>AAO</strong> Convocation—Mechanotransduction and the Interstitium: <strong>The</strong> World In BetweenGregg C. Lund, DO—Rosen Shingle Creek Resort, Orlando, FLVolume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012 <strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Page 7

“<strong>The</strong> difference a DO makes” in welcominghome our troopsWilliam Bograkas, DO, MA, FACOEP, COL, MC, FS USA (retired)<strong>The</strong> human spirit has not changed since Sun Tzuaddressed moral influence with the five fundamentals in<strong>The</strong> Art <strong>of</strong> War 1 and Homer wrote <strong>of</strong> Odysseus’s journey toand from Troy in <strong>The</strong> Illiad 2 and <strong>The</strong> Odyssey. 3 What haschanged, however, is technology and the art <strong>of</strong> medicine.After World War II, our troops returned home by ship.<strong>The</strong>y returned home from Vietnam by plane. During thelong “War on Terror,” our casualties have been treatedand stabilized through the modular Emergency MedicalServices (EMS) system <strong>of</strong> Joint Medical Force 2010.Through excellence in military EMS, survivors, notvictims, have received care and returned stateside within72 to 96 hours. Today, a surge <strong>of</strong> military patients requirethe unity <strong>of</strong> efforts between the Department <strong>of</strong> Defense, theDepartment <strong>of</strong> Veterans Affairs and our civilian medicalcommunities. We shall be judged by the homecomings <strong>of</strong>those we deploy.Recommended reading for those who care forveterans can be found at: www.ncptsd.va.gov,www.DCoE.health.mil and www.biausa.org.References1. Sun T. <strong>The</strong> Art <strong>of</strong> War. Griffith SB, trans. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press;1963.2. Homer. <strong>The</strong> Iliad. Lattimore R, trans. Chicago: University <strong>of</strong>Chicago Press; 1951.3. Homer. <strong>The</strong> Odyssey. Butcher SH and Lang A, trans. New York:P.F. Collier & Son, 1909–14.4. Truhlar RE, ed. Doctor A. T. Still in the Living: His Conceptsand Principles <strong>of</strong> Health and Disease. Cleveland, OH: privatelypublished; 1950.Our own Civil War influenced the teaching andpractice <strong>of</strong> Major Andrew Taylor Still. Let us not forget histeachings when we welcome our Veterans home. <strong>The</strong> laying<strong>of</strong> hands on these patients will restore tissue perfusion andrelieve tissue congestion (tissue memory). We all need t<strong>of</strong>eel the safety <strong>of</strong> home.We all need to remember “an Osteopath asks no favor<strong>of</strong> drugs” 4 and be respectful <strong>of</strong> opiates. Fifty percent <strong>of</strong>patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) selfmedicate—a great challenge in soldiers’ homecomings.Our teachers have taught us the importance <strong>of</strong> treatingboth body and mind. Let us do no harm as we receive ourreturning Veterans.As we treat and unwind the soma, memories release.Trauma to the autonomic nervous system (ANS) is seenin all disasters, not just man-made (war) disasters. Majordepression, anxiety disorders, PTSD and substance abuseare all reported in the disaster psychiatry literature. Asosteopathic physicians, we can make a difference throughthe restoration <strong>of</strong> the ANS, and through our support <strong>of</strong>those in recovery.I hope the reader will find these journal readings <strong>of</strong>value. I am confident that our pr<strong>of</strong>ession will continue towelcome our troops home and practice “the difference aDO makes.”Page 8<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Volume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012

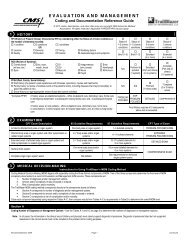

Ultrasound-Guided InjectionsSeptember 7-8, 2012, at UMDNJSOM in Stratford, NJCourse DescriptionThis course is designed for physicians who are novices atsonographic guidance for injections. Under the direction<strong>of</strong> physiatrist Sajid Surve, DO, course participants will beintroduced to the basic principles <strong>of</strong> ultrasound, learn properinjection techniques with ultrasound guidance and learnproper billing and coding for this procedure. Cadavers willbe available for practice, and table trainers will facilitate alow faculty-to-participant ratio. <strong>The</strong> course will focus on theinjection <strong>of</strong> the major joints: glenohumeral, sacroiliac, hip, andknee.Course ObjectivesUpon completion <strong>of</strong> this course, participants will be able to:• Apply the basic principles <strong>of</strong> musculoskeletal ultrasound• Comfortably navigate the necessary equipment requiredfor sonographic guidance <strong>of</strong> injections• Utilize proper injection techniques under sonographicguidance for the glenohumeral, sacroiliac, hip and kneejoints.• Bill, code and document correctly for ultrasound-guidedinjections• Avoid common pitfalls associated with the aboveproceduresCME16 hours <strong>of</strong> AOA Category 1-A credit is anticipatedCourse DirectorsMillicent K. Channell, DO, F<strong>AAO</strong>, is a 2001 graduate <strong>of</strong> thePhiladelphia College <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Medicine. After completingher Family Medicine residency and NeuromusculoskeletalMedicine/Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine (NMM/OMM) residency, she joined the faculty <strong>of</strong> UMDNJSOM in thedepartments <strong>of</strong> OMM and Family Medicine. She has madenumerous scholarly contributions to osteopathic medicine,most notably as co-author <strong>of</strong> the book <strong>The</strong> 5-Minute OsteopathicManipulative Medicine Consult.Sajid A. Surve, DO, is a 2005 graduate <strong>of</strong> the UMDNJSOM.After completing a traditional rotating internship at DelawareCounty Memorial Hospital in Drexel Hill, PA, he became aninaugural resident, and the irst Chief Resident, <strong>of</strong> the PhysicalMedicine and Rehabilitation residency at Long Beach MedicalCenter in Long Beach, NY. He joined the faculty <strong>of</strong> UMDNJSOMin 2009, and completed an NMM/OMM residency in 2010.Course LocationUMDNJSOMOne Medical Center DriveStratford, NJ 08084Course TimesFriday and Saturday: 8:00 am - 5:30 pm (lunch provided)Travel ArrangementsCall Tina Callahan <strong>of</strong> Globally Yours Travel at (800) 274-5975.Registration FormUltrasound-Guided InjectionsSeptember 7-9, 2012Name: ________________________________________ AOA#: _____________Nickname for Badge: _______________________________________________Street Address: ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________City: __________________________________State: ________ Zip: ___________Phone: _______________________________ Fax: ___________________________E-mail: ______________________________________________________________By releasing your fax/e-mail, you have given the <strong>AAO</strong> permission to sendmarketing information regarding courses to your fax or e-mail.Billing Address (if different than above): _________________________________________________________________________________________________Registration RatesOn or before July 9 After July 9<strong>AAO</strong> Member $ 1500.00 $ 1600.00<strong>AAO</strong> Non-Member $ 1600.00 $ 1700.00<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> accepts check, Visa, Mastercard or Discover paymentsin U.S. dollarsCredit Card #: ________________________________________________________Cardholder’s Name: __________________________________________________Expiration Date: _____________________ 3-digit CVV#________________I hereby authorize the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong> tocharge the above credit card for the full course registrationamount.Signature: __________________________________________________________Click here to view the <strong>AAO</strong>’s Cancellation and Refund PolicyPlease submit registration form and payment via mail to the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Osteopathy</strong>,3500 DePauw Blvd., Suite 1080, Indianapolis, IN 46268 or by fax to (317) 879-0563.Or register online at www.academy<strong>of</strong>osteopathy.orgVolume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012 <strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Page 9

Understanding blast-induced traumatic brain injury(bTBI) through mechanisms and patterns <strong>of</strong> injuryPatrick M. Malie, MS, OMS III; Marc Quentin Sonnier, Jr., MS;Murray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPHAbstractObjective <strong>of</strong> review: To provide clinicians and researcherswith a comprehensive, evidence-based overview <strong>of</strong>blast-induced traumatic brain injury (bTBI) and theimplications for a multi-disciplinary approach to treatingmilitary personnel. Understanding the effects <strong>of</strong> that injuryon the human brain is difficult due to the complexity<strong>of</strong> explosive forces. This review introduces new toolsand innovations being applied within the context <strong>of</strong>bTBI research. Understanding blast injury—a commonoccurrence in military combat— by evaluating benchmarksfor concussive or mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI)with computational tools, neuroimaging, epidemiologyand neurophysiology in a multi-disciplinary approachto treatment, will help delineate subsequent effects thatmay complicate recovery and produce the majority <strong>of</strong>manifestations associated with this type <strong>of</strong> injury.Recent findings: Body and vehicular armor reducescombatants’ risk <strong>of</strong> higher severity blast exposure,which tends to increase the rate <strong>of</strong> bTBI incidence. Anincrease <strong>of</strong> mTBI literature has been found in a diverserange <strong>of</strong> science and medical journals from the fields <strong>of</strong>immunology, epidemiology, neuroscience and psychiatry,to computer science and blast forensics. This has improvedunderstanding <strong>of</strong> what differentiates bTBI, post-concussivesyndrome and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) withthe goal <strong>of</strong> improving diagnosis.Conclusions: In the current state <strong>of</strong> the U.S. medicalcrisis, cost-effective solutions are needed to managethe new condition <strong>of</strong> chronic bTBI in our veterans.Understanding neurodegeneration with biomarkers,axonal damage, personality aberrations and inflammatoryresponses aimed at building treatment protocols improvesboth patient outcomes and scientific research progress.Through a multidisciplinary approach to understandingthe mechanisms and patterns <strong>of</strong> injury <strong>of</strong> blast-inducedtraumatic brain injury, research scientists and physicianshope to achieve optimal patient outcomes.IntroductionAs many as 320,000 <strong>American</strong> military combatveterans who have served in the current wars in Iraq andAfghanistan are estimated to have sustained a traumaticbrain injury (TBI) as <strong>of</strong> January 2008. 1 TBI has beendescribed as the “signature injury” <strong>of</strong> Operation Iraqi Freedom(OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). 2-5 <strong>The</strong>growing number <strong>of</strong> conflicts in recent years has led to anunprecedented increase in the use <strong>of</strong> weaponry resultingin blast-induced TBI (bTBI). Such weaponry includesimprovised explosive devices (IEDs), rocket-propelledgrenades (RPG-7 to RPG-29), thermobaric “enhancedblastexplosives,” and explosive-formed projectiles. 6<strong>The</strong> negative effects <strong>of</strong> these devices are felt not only bymilitary personnel, but also civilians. In 2007, roughly14,000 terrorist attacks occurred worldwide, resultingin more than 44,000 injuries and 22,000 deaths, a 20 to30 percent increase from 2006. 7 Moreover, as a result<strong>of</strong> modern warfare, it is estimated that 10 civilians arekilled for every one combatant casualty. 8 <strong>The</strong> studyand management <strong>of</strong> blast-related injuries is not a recentphenomena, despite its increased prevalence in recenttimes. <strong>The</strong> first known documented study <strong>of</strong> blast-relatedhead trauma occurred more than 90 years ago. 9During World War I, British Army physicians Drs.Gordon Holmes and Fred Mott studied soldiers subjectedto blasts who developed neuropsychiatric symptoms. 10Holmes and Mott had trouble differentiating betweenemotional trauma and physical brain injury. 9,11 Suchdifficulties persisted into World War II—some physiciansbelieved there was no brain injury, while others notedelectroencephalography changes similar to those previouslyseen in closed head injuries. 12 Although it was evident thatsecondary and tertiary blast injuries could result in braindamage, it remained unresolved whether primary blastinjuries could directly damage the brain.TBI OverviewTBI is defined as damage to the brain from anexternal mechanical force, including impact, accelerationor deceleration, penetration by a projectile and blastwaves. 13-14 It is an acquired form <strong>of</strong> brain injury. TBI isa complex injury with a broad spectrum <strong>of</strong> disabilitiesand symptoms that can be classified as mild, moderate orsevere, depending on the extent <strong>of</strong> the damage inflicted onthe brain. 15 Brain injury is also known as intracranial injuryPage 10<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Volume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012

Unfortunately, military-associated blast TBI is muchmore complex. Diffuse axonal injury occurs as a result<strong>of</strong> rotational acceleration accompanying indirect loading.Of these rotational injuries, we are most susceptibleto sheer strain. This is due to the large cross-sectionalarea <strong>of</strong> the CNS providing many mediatory paths forcontradicting force vectors and causing both accelerationand deceleration forces. Animal models associate rotationalacceleration with concussion and linear accelerationwith contusions and subdural hematomas without loss <strong>of</strong>consciousness. As the lowest <strong>of</strong> TBI severity, mild bTBIhas a reported prevalence <strong>of</strong> 80 percent spanning threedecades <strong>of</strong> civilian traumatic brain injury. 33,39-41It is evident that many <strong>of</strong> the features observed inanimal models mimicking focal and diffuse TBIs arealso seen in bTBI. 42 According to Cernak and Noble-Haeusslein, 42 common features include vasospasmand barrier disruption, electroencephalogram (EEG)abnormalities, oxidative stress, elevated ICP, metabolicdisturbances and energy failure. Although some reportspropose varying temporal and spatial pr<strong>of</strong>iles, as well as adifferent frequency <strong>of</strong> pathological changes in bTBI versusnon-explosive TBI, other studies suggest a lack <strong>of</strong> strongevidence that blast is categorically different than othermechanisms <strong>of</strong> TBI. 43-45 For instance, Ling, et al., 44 proposethat the occurrence <strong>of</strong> vasospasm, which is <strong>of</strong>ten the cause<strong>of</strong> delayed neurological deterioration, appears to be moretypical following bTBI than other types <strong>of</strong> TBI, suchas penetrating TBI (pTBI) and closed head TBI (cTBI).As a result, military neurosurgeons have had to performdecompressive craniectomies more <strong>of</strong>ten than is typical forpTBI or cTBI. Moreover, there was an increased incidence<strong>of</strong> PTSD symptoms reported among bTBI participants ina study designed to compare patterns <strong>of</strong> performance onneuropsychological measures. 45 However, with respect tocognitive sequelae, it was argued that there is no strongevidence that blast is categorically different than othermechanisms <strong>of</strong> TBI. 45Despite the aforementioned cases noting differingfeatures between bTBI and TBI from other mechanisms, itis still a challenge to confirm or refute a unique signatureclinical description for bTBI. Epidemiologic data aloneis not sufficient in differentiating the less-studied blastinjury features from the more well-known components<strong>of</strong> pTBI and cTBI. 44 Further complicating the issue isthat individuals who experience bTBI are also likely toexperience other severe injuries, including hemorrhagicshock and limb amputation. 42 Addressing other suchinjuries can mask features attributable to bTBI.Predicting Arousal Defects as a Long-TermConsequence <strong>of</strong> Blast-Induced mTBImTBI diagnosis is difficult due to its heavy relianceon patient recall <strong>of</strong> the history <strong>of</strong> the trauma. In the bestcasescenario, eyewitness accounts can substitute forthe memory <strong>of</strong> the injured. As a diagnostic component<strong>of</strong> mTBI, loss <strong>of</strong> consciousness (LOC) is a result <strong>of</strong>functional degradation <strong>of</strong> both cerebral hemispheres <strong>of</strong>the reticular activating system (RAS). Blyth proposes thatmTBI-associated alteration <strong>of</strong> consciousness is caused byinjury to consciousness as a state-dependent structure thatincludes the RAS. This structure is excited by input fromsurrounding sensory tracts, and transmits this excitationto the cortex to induce generalized cortical and behavioralarousal. Within the brainstem reticular formation, it extendsfrom the top <strong>of</strong> the spinal column to the rostral midbrainwith extensions into the thalamus and hypothalamus. 33,46Significant Forces <strong>of</strong> Blast EffectsBlast-induced TBI acts through multiple simultaneousevents occurring in succession, and as a result, canbe categorized according to three distinct actions <strong>of</strong>injury. 47 Blast waves traverse the explosives’ surroundingenvironment with an initial high-pressure shock waveleading to over-pressurization. An explosion createsballistic projectiles within a viscous medium, giving riseto blast-pressure waves. <strong>The</strong>se projectiles, such as blastdebris, lose energy as they propagate toward the greaterforces generating the pressure waves. <strong>The</strong> magnitude <strong>of</strong>these waves is the sum <strong>of</strong> interfering wave points createdas it propagates, signature waves from conserved areas <strong>of</strong>spatial expansion with a consequentially causal collapse,and reflected waves from stiffer boundaries. This property<strong>of</strong> energy dissipation is the inherit magnitude <strong>of</strong> explosiveblast waves. 48<strong>The</strong> over-pressurization mentioned earlier is followedby a subsequent blast wind that causally follows thesubsequent negative pressure created by the shock wavesimilar to an elastic-like pressure recoil. <strong>The</strong> ultimatevector <strong>of</strong> this reverse wind is directed toward the explosivesource, leading to rapid under-pressurization. 49 <strong>The</strong>negative transient pressures associated with reverse windcan create cavitation bubbles that are toxic to neurons.In vitro studies <strong>of</strong> mild TBI discovered induced circuitcrosstalk as a consequence <strong>of</strong> single, mild blast exposures.Multiple blasts increase neuronal tissue susceptibility todamage associated with excitotoxic insult. <strong>The</strong> action <strong>of</strong>primary blast injury relates to the wave action that theblast produces through the mediums it traverses. Tympanicmembrane rupture is generally considered a reliable patientpresentation for primary blast exposure, but interestingly,Page 12<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Volume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012

less than two percent <strong>of</strong> cases in the Madrid, Spain, trainstation explosion experienced pulmonary injury lacking thisindicator.Factors that complicate blast outcomes includeexplosive type, peak over-pressure and its duration, impulseas complex wave forms, location <strong>of</strong> the explosion and itsrelative proximity, environmental hazards, body orientationto the blast and barriers. All these factors impact, as wellas facilitate, bodily insult due to blast exposure. Secondaryacts by blast waves propulsion on fragmented objects thatbecome projectiles. This bTBI is more associated withpenetrating injury where, in the case <strong>of</strong> neurotrauma,the integrity <strong>of</strong> the skull becomes compromised by theblast’s projectiles. <strong>The</strong>se projectiles create superficialpathology that is more apparent than the latter. Mild blastseldom causes injury <strong>of</strong> higher blast severity, but multipleexposures, like those seen in many military personneloverseas, creates acceleration/pressure forces that result inneuron associated soma swelling, nuclear prominence andsometimes neuronal death. 50 In vitro studies focusing onthe effects <strong>of</strong> direct laceration by cell scratching producedfindings that proposed the effects <strong>of</strong> micro-lacerationinduced a greater amount <strong>of</strong> neuronal cellular death thancompared to glial cells.Tertiary is relevant to the surroundings in which theblast’s action mediates a collision. Likely damage can beexpected between the hemispheres separating the cerebrumfrom the cerebellum due to sheer strains. Cytoskeletalalterations, organelle disruption and derangement haveoccurred in studies by Chen 51 when tertiary effects werequantified in vitro as an affect <strong>of</strong> mechanical deformationand quaternary involved burns to surface tissues proximalto those in contact with air, such as the respiratory tractsand skin. <strong>The</strong>se are commonly seen with explosiveweapons capable <strong>of</strong> radiation delivery over largeareas. Injury findings <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong> blast would likelydemonstrate the neuronal damage similarly seen with heavycellular phone use. 42,51-58Computational Modeling <strong>of</strong> Blast InjuryChen describes researchers contrasting the virtualrepresentation <strong>of</strong> geometric deformations <strong>of</strong> blast wavesto that <strong>of</strong> experimentally similar effects <strong>of</strong> induced blasttrauma as an injury predictor. 51 With the aid <strong>of</strong> embeddedmonitoring systems consisting <strong>of</strong> cost-effective, helmetbasednanosensors capable <strong>of</strong> relaying digitalized forceinjury characteristics to a field hospital, medical teamsare able to explore new possibilities <strong>of</strong> guided, long-termtreatment into structurally precise areas <strong>of</strong> perceiveddamage. 59 Some are concerned that helmets, especiallywith the added weight <strong>of</strong> electronic sensors, may contributeto increased cerebral damage. But recent computational,three-dimensional analysis discredited this hypothesiswith findings that are suggestive <strong>of</strong> danger only whenforces are so high that the damage would be similarlydestructive either with or without protective headgear. <strong>The</strong>combined advantage <strong>of</strong> both recorded collateral damagecharacteristics as input for computational cell-deformationand cell-stretching modeling allows for estimates <strong>of</strong>boundary zones between damaged and undamaged areas inthe brain. <strong>The</strong>se data would be used to provide additionalinformation to the more obvious clinical findings. <strong>The</strong>precision <strong>of</strong> finite element models representing blastdynamics upon brain tissue will inevitably increase withmore research to meet the level <strong>of</strong> confidence needed to beuseful for diagnosticians to develop a structured approachto differential diagnosis for blast-related mTBI. 51,52,54,60-64Experimental Study <strong>of</strong> Blast Effects<strong>The</strong> more commonly studied methods forinvestigating blast effects are either by open-air blast,which is <strong>of</strong>ten done on large specimens, or closed-pressuresystems well suited to investigate blast wave kinetics withsmaller specimens in a more controlled fashion. Openairblast studies, while lacking the scalar precision andobjectivity <strong>of</strong> closed-air studies, presents the more realistic,multi-dimensional variability <strong>of</strong> forces experienced by U.S.military forces. One such study has attempted to combinethe more precise, closed-air blast tube investigationwith the varied, multi-mode shock <strong>of</strong> open blast studiesin a cost-effective and highly subjective TBI screeningexperiment as an alternative to the expensive Heliumbasedexperiment. <strong>The</strong> hypothesis is that multi-mode shockdraws correlate the severity <strong>of</strong> brain insult with a pressuretimesignature <strong>of</strong> varied blast signatures in an attempt toassociate a higher relevance to the variety and occasionallyoverlapping nature <strong>of</strong> injuries experienced by deployedcombat troops.Using several characteristically different gas typesin the experiment, expensive helium used to improve thevelocity performance <strong>of</strong> closed shock tube research wasreplaced with relatively inexpensive oxyhydrogen. Italso reduces conditional ischemia as an inherent property<strong>of</strong> the closed experiment’s atmospherically isolatedenvironment. This pressure-time signature compensatesfor the traditional lower resolution peak pressure as ameasure <strong>of</strong> the many different components <strong>of</strong> blast effects.<strong>The</strong> six parameters studied were shock wave velocity,positive phase magnitude, positive phase duration, positivephase impulse, negative phase magnitude, and the impulsedifference between reflected and free-field pressures. Thisallows the degrees <strong>of</strong> damage to be predicted as potentialcontributions <strong>of</strong> individual blast components. Greatercerebral vascular damage was seen using compressed airVolume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012 <strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Page 13

ather than oxyhydrogen <strong>of</strong> similar peak pressure. Thissuggests that this method may be a more realistic and costeffectiveapproach to blast study. 65,66Long-Term Effects Associated with Blast mTBILong-term effects <strong>of</strong> mTBI on the CNS are elusivebecause conflicting findings in scientific and medicalliterature are unclear regarding mechanisms relative tothe nervous system. <strong>The</strong> combination <strong>of</strong> IEDs, along withdramatically improved soldier survivability since theinfancy <strong>of</strong> defining PTSD at the end <strong>of</strong> the Vietnam Warera, has bolstered a significant interest in blast-inducedneural injury. Although animal studies have indeed proventhat, <strong>of</strong> the many varied mechanisms <strong>of</strong> injury, blastoverpressure waves seem to cause the diffuse axonal-type<strong>of</strong> neuropathological injury. 67 TBI injury findings <strong>of</strong> thesemechanisms illustrate primary blast wave as a uniquemechanism and injury variable. 49Blast-induced mild traumatic brain injury (bmTBI),whether occurring in a combat theater or berthing areas,is typically associated with instant, combustion-inducedcephalic blunt trauma, resulting in temporary debilitation <strong>of</strong>neurological functionality. 23Helmet Protection from Blast mTBI<strong>The</strong>re has been much debate to whether helmetprotection adds to or lessens bTBI. Service memberswearing helmets were more likely to withstand both lowerTBI severity and Injury Severity Scores when comparedto those who weren’t, even though the helmet participatedin blast mechanisms. Less than 40 percent <strong>of</strong> IED attackswere accounted for by helmetless TBI as compared to thelarger 82 percent <strong>of</strong> operatives wearing helmets. This smallpercentage <strong>of</strong> victims unprotected from IED blast waslikely attributable to a combination <strong>of</strong> convoy-requiredhelmet use established by military protocol, and theincreased vulnerability that predisposes mobilized groundvehicles to this type <strong>of</strong> attack. Consequently, higher TBIseverity associated with projectile-type weapons, includingtheir associated injury specifics, was significantly higherwhen helmet protection wasn’t available. This is likelythe result <strong>of</strong> ambush or unexpected attacks on militaryservicemen in berthing areas where it is more difficult formilitant extremists to exercise timely IED staging, thuswarranting the use <strong>of</strong> focused weaponry. Unfortunately,these servicemen are most vulnerable because <strong>of</strong> laxedprecaution in these areas, leading to helmet disrobe andsubsequent maximum morbidity. <strong>The</strong>refore, these results,along with current findings, seem fairly agreed that helmetsdo reduce TBI severity. But new helmet designs are neededfor improved facial protection to optimize TBI reductionduring explosive exposure. 62,68ConclusionsSymptoms are not only dependent on the type andseverity <strong>of</strong> TBI, but also by the particular region <strong>of</strong> thebrain that is affected. 15 Mild TBI may result in loss <strong>of</strong>consciousness, while other symptoms include nausea,vomiting, headache, dizziness, difficulty balancing, lack <strong>of</strong>motor coordination, blurred vision, lightheadedness, fatigueor lethargy, tinnitus and changes in sleep patterns. 13,19Emotional and cognitive symptoms associated with mildTBI include behavioral or mood changes, confusion,as well as impairment <strong>of</strong> concentration, attention, andthinking. 15 An individual with moderate or severe TBI maypresent the same symptoms associated with mild TBI, aswell as persistent headache, vomiting and nausea, agitation,restlessness, confusion, loss <strong>of</strong> coordination, slurredspeech, dysarthria, aphasia, weakness or numbness <strong>of</strong>limbs, convulsions and dilation <strong>of</strong> one or both pupils. 13,15,19Long-term symptoms <strong>of</strong> moderate or severe TBIinclude cognitive changes, such as issues with attentionsustainment, processing speed and executive function, aswell as changes in typical social behavior and judgement. 20Cerebral concussive syndromes are common amongthose subjected to explosions, with cognitive deficits andsubstantial memory dysfunction typically resulting. 69 <strong>The</strong>seresults indicate that bTBIs are capable <strong>of</strong> causing cognitivedeficits, particularly problems with memory.Hoge, et al., 70 found mild TBI occurring amongsoldiers deployed in Iraq was strongly correlated withPTSD and other physical health issues months afterreturning home. Furthermore, it was suggested thatboth PTSD and depression were critical mediators <strong>of</strong>the relationship between mild TBI and physical healthproblems. 70-74 Significant correlation was found betweentympanic perforation and unconsciousness in blast-injuryvictims, suggesting a relationship between concussive braininjury and tympanic perforation. 5 It has also been noted thatboth tympanic perforation and primary blast injury werescarce in service members subjected to explosions in therecent US-Iraq conflict. 69,75 This may suggest that tympanicperforation may correlate with concussive brain injury,but not with other primary blast-induced injuries. Furtherstudies need to be conducted to provide insight into therelationship between tympanic perforation and concussivebrain injury.Currently, many features <strong>of</strong> bTBI remain unknown.<strong>The</strong> relatively recent increase in the occurrence <strong>of</strong> bTBIhas warranted a research push to allow for a bettercharacterization <strong>of</strong> the injury. In so doing, the clinicalpersonnel will be better able to provide proper assessmentand treatment techniques. Furthermore, family membersand friends <strong>of</strong> bTBI victims will be better prepared forcoping with effects that may last a lifetime.Page 14<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Volume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012

References1. Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, editors. Invisible Wounds <strong>of</strong> War:Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, <strong>The</strong>ir Consequences, andServices to Assist Recovery. Arlington, VA: Center for MilitaryHealth Policy Research, the Rand Corporation; 2008.2. Martin EM, Lu WC, Helmick K, French L, Warden DL. (2008).Traumatic brain injuries sustained in the Afghanistan and Iraqwars. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Trauma Nursing. 2008;15(3):94-99,100-101.3. Okie S. Reconstructing lives—a tale <strong>of</strong> two soldiers. <strong>The</strong> NewEngland <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medicine. 2006; 355(25):2609-2615.4. Warden D. Military TBI during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. <strong>The</strong><strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2006;21(5): 398-402.5. Xydakis MS, Fravell MD, Nasser KE, Casler JD. Analysis<strong>of</strong> battlefield head and neck injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan.Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2005;133(4):497-504.6. Lew TA, Walker JA, Wenke JC, Blackbourne LH, Hale RG.Characterization <strong>of</strong> craniomaxill<strong>of</strong>acial battle injuries sustainedby United States service members in the current conflicts <strong>of</strong> Iraqand Afghanistan. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Oral and Maxill<strong>of</strong>acial Surgery.2010;68(1):3-7.7. NCTC Report on Incidents <strong>of</strong> Terrorism 2007. NationalCounterterrorism Center Worldwide Incidents Tracking SystemWebsite. http://wits.nctc.gov/Reports.do. Updated April 30, 2008.Accessed January 23, 2010.8. Shuker ST. Maxill<strong>of</strong>acial air-containing cavities, blast implosioninjuries, and management. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Oral and Maxill<strong>of</strong>acialSurgery. 2010;68(1):93-100.9. Mott FW. <strong>The</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> high explosives upon the central nervoussystem. Lancet. 1916;1: 441-49.10. Kocsis JD, Tessler A. Pathology <strong>of</strong> blast-related brain injury.<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2009;46(6):667-672.11. Macleod AD. Shell shock, Gordon Holmes and the Great War.<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Royal Society <strong>of</strong> Medicine. 2004; 97(2):86-89.12. Cramer F, Paster S, Stephenson C. Cerebral injuries due toexplosion waves, cerebral blast concussion: A pathologic, clinicaland electroencephalographic study. Archives <strong>of</strong> Neurology andPsychiatry. 1949; 61(1):1-20.13. Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. Moderate and severe traumaticbrain injury in adults. Lancet Neurology. 2008; 7(8):728-741.14. Parikh S, Koch M, Narayan RK. Traumatic brain injury.International Anesthesiology Clinics. 2007;45(3):119-135.15. National Institute <strong>of</strong> Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).National Institutes <strong>of</strong> Health. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/tbi/tbi.htm. Updated May 6, 2010. Accessed February 17, 2010.16. Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, Butcher I, Lu J, McHughGS, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury:Development and international validation <strong>of</strong> prognostic scoresbased on admission characteristics. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5(8):165.17. Zink BJ. Traumatic brain injury. Emergency Medicine Clinics <strong>of</strong>North America. 1996;14(1):115-150.18. Narayan RK, Michel ME, Ansell B, Baethmann A, Biegon A,Bracken MB, et al. Clinical trials in head injury. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong>Neurotrauma. 2002;19(5):503.19. Bagiella E, Novack TA, Ansel B, Diaz-Arrastia R, Dikmen S, HartT, et al. Measuring outcome in traumatic brain injury treatmenttrials: Recommendations from the traumatic brain injury clinicaltrials network. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2010;25(5):375-382.20. Halbauer JD, Ashford JW, Zeitzer JM, Adamson MM, Lew HL,Yesavage JA. Neuropsychiatric diagnosis and management <strong>of</strong>chronic sequelae <strong>of</strong> war-related mild to moderate traumatic braininjury. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Rehabilitation Research and Development.2009;46(6), 757-796.21. Finkel MF. <strong>The</strong> neurological consequences <strong>of</strong> explosives. <strong>Journal</strong><strong>of</strong> the Neurological Sciences. 2006; 249(1):63-67.22. Cernak I, Wang Z, Jiang J, Bian X, Savic J. Ultrastructural andfunctional characteristics <strong>of</strong> blast injury-induced neurotrauma. <strong>The</strong><strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Trauma. 2001;50(4): 695-706.23. Masel BE, DeWitt DS. Traumatic brain injury: a disease process,not an event. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Neurotrauma. 2010;27(8):1529-1540.24. Halbauer JD, Ashford JW, Zeitzer JM, Adamson MM, Lew HL,Yesavage JA. Neuropsychiatric diagnosis and management <strong>of</strong>chronic sequelae <strong>of</strong> war-related mild to moderate traumatic braininjury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009; 46(6):757-796.25. Elder GA, Mitsis EM, Ahlers ST, Cristian A. Blast-induced mildtraumatic brain injury. Psychiatric Clinics <strong>of</strong> North America.2010;33(4):757-781.26. Bhattacharjee Y. Shell shock revisited: Solving the puzzle <strong>of</strong> blasttrauma. Science. 2008;319(5862): 406-408.27. Brenner LA, Vanderploeg RD, Terrio H. Assessment anddiagnosis <strong>of</strong> mild traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stressdisorder and other polytrauma conditions: Burden <strong>of</strong> adversityhypothesis. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54(3):239-246.28. Brenner LA, Terrio H, Homaifar BY, Gutierrez PM, Staves PJ,Harwood JE, et al. Neuropsychological test performance insoldiers with blast-related mild TBI. Neuropsychology. 2010;24(2):160-167.29. Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Cox AL, Engel CC, Castro CA.Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq.New England <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medicine. 2008;358(5):453-463.30. Martin EM, Lu WC, Helmick K, French L,Warden DL. TraumaticBrain Injuries Sustained in the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars. <strong>Journal</strong><strong>of</strong> Trauma Nursing. 2008;15(3):94.31. Ling G, Bandak F, Armonda R, Grant G, Ecklund J. Explosiveblast neurotrauma. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Neurotrauma. 2009;26(6):815-25.32. Jones E, Fear NT, Wessely S. Shell shock and mild traumatic braininjury: A historical review. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1641-1645.33. Blyth BJ, Bazarian JJ. Traumatic Alterations in Consciousness:Traumatic Brain Injury. Emergency Medicine Clinics <strong>of</strong> NorthAmerica. 2010;28(3):571-594.34. Baskin TW, Holcomb JB. Bombs, mines, blast, fragmentationand thermobaric mechanisms <strong>of</strong> injury. In: Mahoney PF, Ryan J,Brookes A, Schwab CW, eds. Ballistic Trauma: A Practical Guide.London: Springer-Verlag;2005:45-66.35. Vanderploeg RD, Belanger HG, Curtiss G. Mild traumatic braininjury and post-traumatic stress disorder and their associationswith health symptoms. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(7):1084-1093.36. Warden D. Military TBI during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. JHead Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21(5):398-402.37. Sbordone RJ and Liter JC. Mild traumatic brain injury does notproduce post-traumatic stress disorder. Brain Inj. 1995;9(4):405-412.38. DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD, Gandy S. Traumatic braininjury—Football, warfare and long-term effects. N Engl J Med.2010;363(14):1293-1296.39. Thompson JM, Scott KC, Dubinsky L. Battlefield brain:Unexplained symptoms and blast-related mild traumatic brainVolume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012 <strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Page 15

Page 16injury. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(11):1549-1551.40. Auerbach JM, Segal M. Muscarinic receptors mediatingdepression and long-term potentiation in rat hippocampus. <strong>The</strong><strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Physiology. 1996;492(2):479.41. Beck AT, Alford BA. Depression: Causes and treatments.Philadelphia: University <strong>of</strong> Pennsylvania Press; 2009.42. Cernak I, Noble-Haeusslein NJ. Traumatic brain injury: Anoverview <strong>of</strong> pathobiology with emphasis on military populations. JCereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(2):255-266.43. Armonda RA, Bell RS, Vo AH, Ling G, DeGraba TJ, Crandall B,et al. Wartime traumatic cerebral vasospasm: Recent review <strong>of</strong>combat casualties. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(6):1215-1225.44. Ling G, Bandak F, Armonda R, Grant G, Ecklund J. Explosiveblast neurotrauma. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Neurotrauma. 2009; 26(6):815-825.45. Belanger HG, Kretzmer T, Yoash-Gantz R, Pickett T, Tupler LA.Cognitive sequelae <strong>of</strong> blast-related versus other mechanisms <strong>of</strong>brain trauma. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> the International NeuropsychologicalSociety. 2009; 15(1):1-8.46. Vanderploeg RD, Curtiss G, Belanger HG. Long-termneuropsychological outcomes following mild traumatic braininjury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11(3): 228-236.47. Elsayed NM. Toxicology <strong>of</strong> blast overpressure. Toxicology.1997;121(1): 1-15.48. Courtney A, Courtney M. A thoracic mechanism <strong>of</strong> mild traumaticbrain injury due to blast pressure waves. Med Hypotheses.2008;72(1): 76-83.49. Howe LL. Giving context to post-deployment post-concussive-likesymptoms: blast-related potential mild traumatic brain injury andcomorbidities. Clin Neuropsychol. 2009; 23(8): 1315-1337.50. Wolf SJ, Bebarta VS, Bonnett CJ, Pons PT, Cantrill SV. Blastinjuries. <strong>The</strong> Lancet. 2009;374(9687): 405-415.51. Chen YC, Smith DH, Meaney DF. In-vitro approaches for studyingblast-induced traumatic brain injury. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Neurotrauma.2009;26(6):861-876.52. Cullis I. Blast waves and how they interact with structures. J RArmy Med Corps. 2001;147(1): 16-26.53. Ritenour AE, Baskin TW. Primary blast injury: update ondiagnosis and treatment. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(7):S311.54. Sogbesan EA. Design and Analysis <strong>of</strong> Blast Induced TraumaticBrain Injury Mechanism Using a Surrogate Headform:Instrumentation and Outcomes. Nebraska Univ.-Lincoln, Dept. <strong>of</strong>Mechanical Engineering. Master’s <strong>The</strong>sis. May 2011.55. Margulies S, Hicks R. Combination therapies for traumatic braininjury: prospective considerations. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Neurotrauma.2009;26(6): 925-939.56. Cernak I, Savic J, Ignjatovic D, Jevtic M. Blast injury fromexplosive munitions. J Trauma. 1999; 47(1):96-104.57. Moore DF, Radovitzky R, Shupenko L, Klin<strong>of</strong>f A, Jaffee MS,Rosen JM. Blast physics and central nervous system injury. FutureNeurol. 2008; 3(3): 243-250.58. Moore DF, Jaffee MS. Military traumatic brain injury and blast.Neuro Rehabilitation. 2010;26(3): 179-181.59. Watkin KL, Iyer R, Karbalczyk Z, Sanders W, Patel J. HelmetIntegrated Nanosensors, Signal Processing and Wireless RealTime Data Communication for Monitoring Blast Exposure toBattlefield Personnel. Report for U.S. Army Medical Research andMateriel Command, Ft. Detrick, Maryland. Dec 2009.60. Grujicic M, Bell WC, Pandurangan B, Glomski PS. Fluid/structureinteraction computational investigation <strong>of</strong> blast-wave mitigationefficacy <strong>of</strong> the advanced combat helmet. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> MaterialsEngineering and Performance. 2011; 20(6):877-893.61. Harrisson S, Kirkman E, Mahoney P. Lessons learnt fromexplosive attacks. J R Army Med Corps. 2007;153(4):278-282.62. Nyein MK, Jason AM, Yu L, Pita CM, Joannopoulos JD, MooreDF, et. al. In silico investigation <strong>of</strong> intracranial blast mitigationwith relevance to military traumatic brain injury. Proceedings <strong>of</strong>the National <strong>Academy</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sciences. 2010;107(48): 20703-20708.63. Nyein MK. Computational modeling <strong>of</strong> blast-induced traumaticbrain injury. Mass. Inst.<strong>of</strong> Technology, Dept. <strong>of</strong> Aeronautics andAstronautics. <strong>The</strong>sis. 2010.64. Moore DF, Jerusalem K, Nyein MK, Noels L, Jaffee MS,Radovitzky RA. Computational biology—modeling <strong>of</strong> primaryblast effects on the central nervous system. Neuroimage.2009;47:T10-T20.65. Reneer DV, Hisel RD, H<strong>of</strong>fman JM, Kryscio RJ, Lusk BT, GeddesJW. A multi-mode shock tube for investigation <strong>of</strong> blast-inducedtraumatic brain injury. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Neurotrauma. 2011;28(1):95-104.66. Cernak I, Merkle AC, Koliatsos VE, Bilik JM, Luong QT, MahotaTM, et. al.<strong>The</strong> pathobiology <strong>of</strong> blast injuries and blast-inducedneurotrauma as identified using a new experimental model <strong>of</strong>injury in mice. Neurobiology <strong>of</strong> Disease. 2011;41(2):538-551.67. Elder GA, Cristian A. Blast-related mild traumatic brain injury:mechanisms <strong>of</strong> injury and impact on clinical care. Mt Sinai J Med.2009;76(2):111-118.68. Macgregor AJ, Dougherty AL, Galarneau MR. Injury-specificcorrelates <strong>of</strong> combat-related traumatic brain injury in operationIraqi freedom. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2011;26(4):312-318.69. Wolf SJ, Bebarta VS, Bonnett CJ, Pons PT, Cantrill SV. Blastinjuries. Lancet. 2009;374(9687): 405-415.70. Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Cox AL, Engel CC, Castro CA.Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq.<strong>The</strong> New England <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medicine. 2008; 358(5):453-463.71. Bryant RA, O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, McFarlane AC, ClarkR, Silove D. <strong>The</strong> psychiatric sequelae <strong>of</strong> traumatic injury. Am JPsychiatry. 2010;167(3): 312-320.72. Lannoo E, Colardyn F, Jannes C, de Soete G. Course <strong>of</strong>neuropsychological recovery from moderate-to-severe head injury:a 2-year follow-up. Brain Injury. 2001;15(1):1-13.73. Snell FI, Halter MJ. A signature wound <strong>of</strong> war: mild traumaticbrain injury. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2010;48(2): 22-28.74. Bryant RA. Disentangling mild traumatic brain injury and stressreactions. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358(5):525-527.75. Harrison CD, Bebarta VS, Grant GA. Tympanic membraneperforation after combat blast exposure in Iraq: A poor biomarker<strong>of</strong> primary blast injury. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Trauma. 2009: 67(1): 210-211.Accepted for publication: June 2012Address correspondence to:Patrick M. Malie, MS, OMS III; Marc Quentin Sonnier, Jr., MS;Murray R. Berkowitz, DO, MA, MS, MPHDepartment <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Manipulative MedicinePhiladelphia College <strong>of</strong> Osteopathic Medicine—Georgia Campus625 Old Peachtree Road NWSuwanee, Georgia 30024murraybe@pcom.edu<strong>The</strong> <strong>AAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Volume 22, Issue 2, Summer 2012