Seattle: 1900-1920 -From Boomtown, Through Urban Turbulence ...

Seattle: 1900-1920 -From Boomtown, Through Urban Turbulence ...

Seattle: 1900-1920 -From Boomtown, Through Urban Turbulence ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

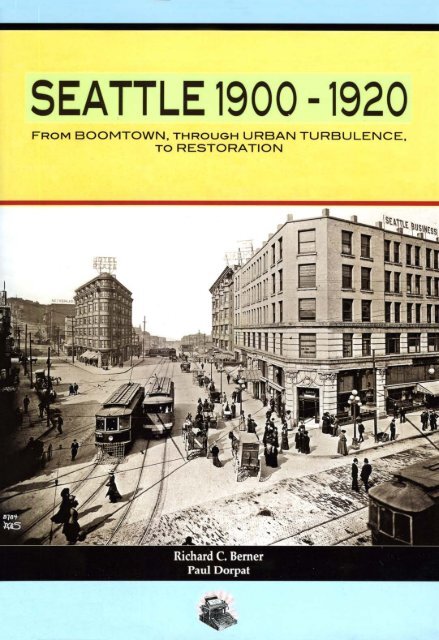

<strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>1900</strong> - <strong>1920</strong><strong>From</strong> <strong>Boomtown</strong>,<strong>Through</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Turbulence</strong>,To RestorationRichard C. BernerPaul Dorpat

Table of ContentsIntroduction.....................................................................1Part One<strong>Seattle</strong> at the Turn of the Century....................................4Manufacturing .................................................................7Fight for Control of the Waterfront................................10Seeding of the Municipal Ownership Movement..........18Industrial Relations........................................................24City Politics, <strong>1900</strong>–1904: The Traditional Period.........29Social Fabric of the City................................................32Popular Entertainment...................................................45Education.......................................................................60Part TwoCity Politics, 1904–1912: Progressivism Emerges........66Part ThreeThe Economy, Labor, and Politics, 1913–1917.............90Industrial Relations......................................................101City Politics, 1914–1916.............................................108Part FourWar Time: Preparedness to Belligerency...............130Shipyard Strike: “Thunder on the Left” ......................149Part FiveThe 1919 Shipyard Strike and the General Strikeand Its Aftermath..........................................................159Epilogue.......................................................................189Bibliography................................................................192Index............................................................................201

DedicationIn memory ofMurray MorganandRobert E. Burke

AcknowledgementsiiiKaryl Winn, retired Head of Manuscripts & UniversityArchives DivisionGlenda Pearson, Head of Microform & NewspaperCollections, University of WashingtonCarla Rickerson, Gary Lundell, Janet Ness, SpecialCollections, U.W. LibrariesSara Early, Editor of the Pacific Northwest Quarterly forher editing of the revised editionEleanor Toews, <strong>Seattle</strong> Public Schools ArchivistScott Cline, Anne Frantilla, <strong>Seattle</strong> Municipal ArchivesCarolyn Marr, Museum of History and IndustryLibrarianJodee Fenton, <strong>Seattle</strong> Public Library, <strong>Seattle</strong> RoomAndrea Flower, designer of the revised editionErin Stallings, proofreader of the revised edition

PrefaceThe original volume of my three volume <strong>Seattle</strong> in the 20th Century (<strong>1900</strong>-1950)elicited many positive published reviews and informal critiques. Titled <strong>Seattle</strong> <strong>1900</strong>-<strong>1920</strong>:<strong>From</strong> <strong>Boomtown</strong>, <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Turbulence</strong>, To Restoration, the late Murray Morgan consideredit to be “by far the most informative history of the period when <strong>Seattle</strong> rose to dominance inthe Pacific Northwest.” Portland’s historian E. Kimbark MacColl wrote it “should stand asthe most definitive account of <strong>Seattle</strong>’s historic growth for many years to come.” QuintardTaylor added “The book’s other major strength is the tracing of themes usually relegatedto the fringes of urban history—labor activism, popular entertainment, the City Beautifulmovement, the university and the city.”These and other favorable comments encouraged me to consider a revised edition,one that would this time be subjected at the onset to professional editing to overcomecompositional and writing deficiencies of the original.The most obvious improvement, though, is the incorporation of historicalphotographs by Paul Dorpat, whose unique familiarity with <strong>Seattle</strong>’s history has resultedin photographs and captions placed in context that lend both illustrative depth and asense of historical transition to my somewhat lean institutional history. For a statewidecontext dealing specifically with public works readers will benefit by referring to BuildingWashington: A History of Washington State Public Works, by Dorpat and GenevieveMcCoy. As much as I had wished to revise this volume in all probability I would not haveattempted it had Paul not agreed to collaborate.What distinguishes this history is its unique exploration of archival/manuscriptholdings of the University of Washington Libraries that I and my colleague Karyl Winnaccumulated over a period of more than thirty years. That she persuaded Puget SoundPower and Light (currently Puget Sound Energy) to donate their records to the Universitymade it possible to document the public power movement more fully by having access torecords of the dominant private utility in western Washington—here already were recordsin the collection representing proponents of public power. Their records also added muchunique documentation of industrial relations. The company—at the center of much of theregion’s history – is to be congratulated for making access possible for studies such as thisand others sure to follow.Should the reader refer to the bibliography in the list of theses and dissertationstake note of the dates when they were written. A substantial number were written before1960 and thereby had practically no benefit from archival sources collected after 1959, oneyear from the formal establishment of the Manuscript Collection under administration ofa professional curator. Those written subsequently did use these source materials oftenas they were being accessioned. None, incidentally, used Puget Sound Power & LightCompany records because they were not acquired until 1972, though not explored until mystudy began in 1985.Such graduate studies, leading to masters and doctoral degrees, constitute thebuilding blocks for research by others. Many were subsequently published in articleform in periodicals; some substantially in whole. In whatever format they are inherentlyrevisionist in character by reason of their use of archival sources to which additions arebeing continuously acquired.

IntroductionIntroductionIn presenting a comprehensive history of <strong>Seattle</strong> in its twentieth century, I wasdrawn as if by a magnet to the city’s politics and economy. It is the combination of politicsand economics that produces the wealth that allows society to function. William Greiderobserves in Who Will Tell the People? that politics “exists to resolve the largest questions ofthe society. . . . At its best, politics creates and sustains social relationships. . . . Democracypromises to do this through an inclusive process of conflict and deliberation, debate andcompromise.” During the period covered in this and the second volume (<strong>1900</strong>–1940),corporate structures—including businesses, trade associations, and elitist social clubs—dominated the economy and politics, which in turn protected and advanced their interests.At the turn of the century, these corporate structures were beingchallenged nationally and locally by countervailing forces thatbecame known as the Progressive Movement.*Signaling the onset of the movement, PresidentTheodore Roosevelt successfully intervened in the 1902 strikeon behalf of the anthracite miners and created a conciliationboard to settle future disputes. Further illustrating this shiftaway from uninhibited corporate power, Roosevelt broke upthe Northern Securities Company in 1904. The company hadeffectively established a monopoly with its consolidation ofthe Great Northern, the Northern Pacific, and the Burlingtonrailroad corporations and could fix freight rates at whateverlevel it chose. At the turn of the century railroad corporationsdominated politics in most states, including Washington. Thisdomination allowed the arbitrary setting of freight rates thatcaused the Populist Party to form and figured prominentlyin the reform agenda of the more urban-based ProgressiveMovement.Waterborne commerce was <strong>Seattle</strong>’s economic base.The railroad companies controlled the waterfront, settingwharfage rates and impeding construction of a union station.It was inevitable that the business community at large wouldbegin to oppose the railroad companies’ control once its leadersfound these companies blocking the way to the commercialexpansion that they anticipated would come with the opening ofthe Panama Canal. These free enterprise business leaders joinedwith proponents of public ownership to pass in 1911 an actallowing the creation of municipal corporations for port cities.With this act the Port of <strong>Seattle</strong> was born.With this broadside theNorthern Pacific Railroadheadlines its contributionto the twentieth century:daily service between<strong>Seattle</strong> and St. Paul onthe railroad’s luxuriousNorthcoast Limited. It is theaccomplishment of a century(roughly) of advances increaturely comforts sinceLewis and Clark first blazedthe route.* John K. Galbraith, American Capitalism: The Concept of Countervailing Power (Boston:Houghton Mifflin, 1962). See also Kevin Phillips, Wealth and Democracy: A Political History of theAmerican Rich (New York: Broadway Books, 2002). Phillips in effect updates Galbraith, placing thedevelopment of American capitalism in a larger historical context by comparing it with the rise andfall of previously dominant Western economic powers.

IntroductionCedar River Taste. During an 1899 visit to the Cedar Rivertwo unidentified members of the <strong>Seattle</strong> City Councilshow their appreciation for the taste of the water thatwould soon replace Lake Washington as the primarysource of drinking water for the community.The public ownership movementgrew out of the City of <strong>Seattle</strong>’s attempts tocontrol its water supply in the mid-1890s.Once it acquired that control, the city alsobegan to generate hydroelectric power atthe Cedar River reservoir, putting it in competition with the <strong>Seattle</strong> Electric Company ofthe Stone and Webster Management Corporation. The stage was hereby set for a titanicpolitical conflict running throughout the period from <strong>1900</strong> to 1940. The public powermovement was statewide, involving the two municipally owned systems of Tacoma and<strong>Seattle</strong> as well as the Washington State Grange, all of which were united against the state’sprivate power companies. The movement climaxed in 1930, when voters approved Initiative1, which authorized the creation of public utility districts. But this merely expanded theconflict, extending it to the Columbia River basin and necessitating the involvement of thefederal government.Public ownership was the single issue around which reformers gathered duringthe first two decades of the century; it brought together organized labor, the WashingtonFederation of Women’s Clubs, the Ministerial Federation (forerunner of the Council ofChurches), and the Municipal League—all, including organized labor, staunchly middleclass. This constituency was held together by its dedication to public power. The issue ofpublic power became morally charged in a way that vice and police corruption—whichproved to have an ephemeral constituency—did not.Central to industrial relations was the contest between employers, who pressed forthe open shop, and labor unions, which wanted the closed shop. In the open shop, employersbargained with employees individually; in the closed shop, employers bargained with theunions, which acted on behalf of the employees. Employers emerged victorious from the1919 General Strike, sustaining their version of the open shop, known nationwide as theAmerican Plan, until 1934. Under federal protection, the union movement revived in 1934,and organized labor once again became politically active, forming a coalition with otheraggrieved groups to constitute New Deal liberalism.The <strong>Seattle</strong> public school system and the University of Washington were funded bythe state through an inherently political process. Both depended upon state tax revenues forfunding; the public schools were financed by local property taxes as well. During the firsttwo decades of the century, <strong>Seattle</strong>’s schools were relatively well funded because the city’supwardly mobile middle class enthusiastically supported the forward-looking educationalpolicies of the superintendent, Frank B. Cooper. However, he and his successors had todeal with a successful tax revolt in 1921 led by leaders of the business community, justas fresh demands were being placed on the school system to adapt to rapid technologicalchanges in business and mass production. Passage of the forty-mill limitation on propertytaxes in 1932, combined with the effects of the Great Depression, further complicatedpublic school funding. The University of Washington was also affected.

IntroductionCivil liberties protections were gradually extended to the general populationthrough the combined efforts of the Central Labor Council of <strong>Seattle</strong>, the WashingtonFederation of Women’s Clubs, and the Ministerial Federation. Traditionally, the courts andthe constabulary rarely protected civil liberties, and they did so even less often as tensionsrose during events just preceding U.S. involvement in the Great War. During the war, civilliberties came under attack from a federalized vigilantism, to which local authorities lentpatriotic cover. Trade unionism in particular was affected, because maintaining the openshop required curtailing free speech and free assembly. Sympathetic courts readily respondedwith injunctions against strike action. During the next two decades, civil libertarians weremet with frustration when trying to undo the legislation and questionable incarcerations ofthe war and early postwar years and when seeking elemental First Amendment protectionsfor free speech and free assembly.All through the period, issues of morality erupted, and reformers focused upon thepolice protection offered to vice operators. Before 1911 it was often these issues of moralitythat caused disparate groups to act collectively to gain political reform. These successes ledto more direct citizen participation in the political process: the initiative, referendum, andrecall. While winning these reforms, citizens also developed instruments of home rule tocombat the influence of absentee owners, in particular the railroads and utility franchises.Home rule as a concept came to <strong>Seattle</strong> in the wake of its success in the 1890s in cities suchas Buffalo, San Francisco, Cleveland, Toledo, and St. Louis.Public welfare programs before 1933 had depended upon private charity andcounty funding and provided relief primarily to the deaf and blind, the indigent poor, anddependent children. These programs did not provide work relief for the unemployed. Thelong-term unemployment of the Great Depression lay far beyond their scope for a poor lawmentality persisted until challenged in the 1930s, whenindigence no longer had to be proved. Nonetheless,even then the mind-set persisted in conservative statepolicies and the governor, though a Democrat, opposedNew Deal programs. This led to bitter fights over theadministration of unemployment and outdoor relief,and these struggles preoccupied government officials atevery level and the citizenry at large.Inspired in part by the formation of Mount RainierNational Park in 1899, the Washington Federation ofWomen’s Clubs in 1904 lobbied for the creation ofthe Elk National Park on the Olympic Peninsula. TheMountaineers club, created in 1906, frequently joinedArgus, the often acerbic <strong>Seattle</strong> weeklyof political opinion and reporting, isconsistently kind towards Frank B.Cooper with its own caption to theschool administrator’s caricature.“Mr. Cooper is superintendent of<strong>Seattle</strong>’s very excellent public schoolsystem, of which he has a right to feelproud.forces with the Federation, most emphatically in thefight to establish the Olympic National Park in the 1930s,when the chief opponent was the U.S. Forest Service,long allied with logging interests. Our contemporaryconservation movement took root in this depression-timestruggle with the Forest Service, although from 1938 to1950, conservative forces, finding cover in the wartime

Part Oneemergency and onset of the cold war, steadily eroded the liberal programs launched underthe New Deal and sparked even earlier by the Progressive Movement during the years wewill now survey.Part One<strong>Seattle</strong> at the Turn of the CenturyThe arrival of the SS Portland from the Klondike on 17 July 1897, with its “ton ofgold,” launched <strong>Seattle</strong>’s twentieth-century economy. The city was favorably positioned fordeveloping trade not only with Alaska but also with Asia. James J. Hill’s Great NorthernRailroad (GN) had finally given the city its own transcontinental connection with marketsto the east in 1893—ten years after the Northern Pacific Railroad (NP) had connectedTacoma’s lumber mills with eastern markets. <strong>Seattle</strong>ites never fully forgave the NP forkindling rivalry with its neighbor down the Sound. But the depression of 1893 to 1896 hadput a damper upon <strong>Seattle</strong>’s early commercial development. With the Portland’s berthing,the city began to throb at the prospect ahead.During previous decades, the nascent city’s merchants had steadily cultivatedtrading relationships with southeast Alaska, British Columbia, and the Puget Soundhinterland. <strong>Seattle</strong> became the regional jobbing and trading center by the early 1890s.Though the commodities traded were ever so humble, a solid commercial base was beinglaid for subsequent expansion. Most traded were groceries, followed by dry goods, meat,hardware, and machinery. Small vessels, nicknamed the Mosquito Fleet, swarmed over thesound carrying lesser commodities: local farm products, lumber, and fish, all of which wereexchanged for processed foods and farm and household supplies.That the vessel that ignited the goldrush should be named for <strong>Seattle</strong>’sprinciple commercial rival was anirony no doubt enjoyed by thosehere crowding the waterfront underthe influence of “Gold Fever.” Theexhilarated crowd admires thesteamship Portland resting in itssnug slip between Schwabacher’swharf and the Pike Street Fish Wharf,the present site of Waterfront Park.Puget Sound is considerably closerto the wealth of Alaska than theColumbia River and <strong>Seattle</strong> exploitedthis advantage. The pioneers werepleased to call Puget Sound the“Mediterranean of the Pacific.” It hadno perils at its entrance like the barat the mouth of the Columbia River.Any passage to Portland was madeunpredictable when passing throughthat “Graveyard of the Pacific.”

<strong>Seattle</strong> at the Turn of the CenturyAs though by design, small local railroads complemented this waterbornecommerce with the hinterland. Coal, carried by rail to <strong>Seattle</strong> from the Green River,Newcastle, and Issaquah coalfields, constituted the city’s second largest export before theturn of the century. Coal bunkers of the Oregon Improvement Company and the NorthernPacific snaked into Elliott Bay via Railroad Avenue. The coal was then shipped mainly toCalifornia.Gold discoveries in Alaska simply stimulated the city’s merchants to expandexisting operations. According to John Rosene, head of the Northwest CommercialCompany in Alaska, <strong>Seattle</strong> interests controlled ninety percent of the ships involved inthe Alaska trade after 1905. By 1912 salmon would displace gold as the foundation of theAlaska trade. Canned salmon from Alaska and from Puget Sound, raw silk from Japan, andlumber from Sound mills provided the Great Northern with commodities that were boundfor midwestern and eastern markets. The GN already had plenty of freight to supply Asiaand Alaska: heavy machinery, hardware, cotton, grain, general merchandise, and cannerysupplies chief among them.When extending his railroad to <strong>Seattle</strong>, Hill had trade with Asia foremost in mind.Between 1895 and 1896, commerce with Japan had doubled. It then tripled the next year.Between 1895 and <strong>1900</strong>, the city’s waterborne commerce had expanded eightfold. Theyear 1901 saw the Asian trade double as both the Nippon Yushen Kaisha Line (whichhad been handling GN cargo since 1896) and Hamburg’s Kosmos Line expanded serviceand the China Mutual Line entered the market. In 1905 Hill contributed the “two largestcargo carriers afloat,” the SS Minnesota and SS Dakota, which carried cargo to and fromYokohama, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Manila (trade with Manila stemmed from U.S.seizure of the Philippines from Spain in 1898). Other lines were steadily added to portoperations in <strong>Seattle</strong>. By <strong>1920</strong> about thirty shipping companies sailed regularly from ElliottBay.In 1908 the pioneerColman family extendedits formerly modest dockto 705 feet and topped itwith a landmark tower intime for the “MosquitoFleet” buzz of 1909. Itwas the year of thecity’s Alaska YukonPacific Exposition andElliott Bay was crowdedwith excursions. In thisportrait of the youngwharf a full flotilla ofsteamers lines its northslip. On the outsideCourtesy, Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society. #5011-17is the City of Everettreminding us with abanner to “Stop Over in Everett.” One of the larger steamers on the Sound, the Indianapolis, is on the right. Itserved the route between <strong>Seattle</strong> and Tacoma, the busiest on Puget Sound. In the booming spirit of 1909 the “Cityof Destiny” on Commencement Bay promised with signs of many sizes posted on sites along the busy east shoreof Puget Sound, “You’ll Like Tacoma.”

Part OneWhen Railway and Marine Newsbegan publishing in 1904, its editorsnoted that most of the improvements onthe waterfront had been made since <strong>1900</strong>and that the Northern Pacific and thePacific Coast Company alone had builteighteen new piers and warehouses in thenew century. “In general terms it may bestated that the wharfs and warehouses of<strong>Seattle</strong> are owned and controlled by thethree great transportation companies: theGreat Northern Railway Company, theNorthern Pacific Railway Company andthe Pacific Coast Company.” The last, thesuccessor to the Oregon ImprovementCompany, operated exclusively in thecoastal trade, using the ships of itsaffiliate, the Pacific Coast SteamshipCompany.In 1903 one of the mainstays of <strong>Seattle</strong>’s pioneer economy,the coal wharf and bunkers at King Street, was razed andreplaced three blocks south at Dearborn Street with thetwin towers of the Pacific Coast Company—successorsto the pioneer Oregon Improvement Company. In the1960s the landmark towers were razed like much elsesouth of King Street for construction of the sprawlingPier 46 container yard.The NP soon dropped out of the marine business. Independent wharfs, where theMosquito Fleet operated, catered to the trade in Alaska and Puget Sound. These wharfs,Railroad Avenue reached its full width in the first years of the twentieth century. It held nine parallel tracksplus a planked extension on the bay side for wagons to reach the new railroad finger piers. This view of itlooks north from Yesler Way. The sprawling Columbia Street Depot is on the right. Built after the 1889 fire itwas at various times home to the <strong>Seattle</strong> Lake Shore and Eastern Railroad, the Northern Pacific, and the GreatNorthern. After the new King Street Union Depot opened in 1905 this clapboard terminus was kept for oddassignments until it was razed in 1910.

scattered among the docks ownedby the railroad companies, consistedmainly of shipyards, boiler works, andmetalworking and cordage plants. Railtransshipment was a major component ofthe city’s economy, employing not onlyrailroad workers but also those involvedin the maritime trades. As the Asian tradesteadily expanded, the rail transshipmentbusiness grew with it: raw silk, tea,curios, matting, and braid traveled byrail to the eastern United States. In fact,special express trains carried the raw silkManufacturingThe Great Northern Railroad’s Pacific Rim behemoths,the SS Minnesota and SS Dakota, berthed bow-to-sternat the railroad’s Smith Cove docks, ca. 1907.to Hoboken, New Jersey, and were given priority over all other traffic including passenger,mail, and the Great Northern’s mainstay, lumber.ManufacturingAt the turn of the century, construction firms dominated <strong>Seattle</strong>’s manufacturingsector, as the city’s population boomed from 80,671 in <strong>1900</strong> to 237,000 in 1910. Apartfrom construction companies, manufacturing firms were usually small, catering to localand regional needs. In <strong>1900</strong>, fourteen woodworking mills employed an annual average ofonly 1,008 wage earners, while construction firms employed 1,372 workers. Constructionworkers were kept fully employed during the first decade of the century, meeting thedemand for housing, warehouses, office buildings, and retail stores; they were also keptThe Columbia and PugetSound depot opened nearthe foot of WashingtonStreet in 1905, one yearearlier than the longanticipatedKing StreetUnion Depot. This smallerCPS depot sat in themiddle of Railroad Avenueand over the formersite of “Ballast Island,”the off-shore mound of“foreign soil” carried hereoriginally as ship’s ballast.With many additions andextensions, the PacificCoast Company’s Pier B—seen here above thedepot—survives as Pier48, the last of the fingerpiers south of Yesler Way.

Part Onebusy installing utilities and leveling the city’s downtown hills. Housing constructionpeaked in the years 1908 1909 as the city geared up for the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-PacificExposition. By 1907 the number of lumber mills had doubled, though none of <strong>Seattle</strong>’smills approached the size of Tacoma’s. While Tacoma’s twenty-one mills, keyed to theexport and Midwest markets, produced about 80,000 board feet a day, <strong>Seattle</strong>’s twentysevenmilled only 47,000 board feet a day.Spurred by the demand in Alaska for boats and barges, machinery, and heavy andlight hardware, the shipbuilding and foundry industries expanded steadily throughout thefirst two decades of the century. The pioneer Clarence Bagley noted a dozen shipyardsemploying about nineteen hundred men at the beginning of the century. Moran Brothers’yard, the city’s largest, was subsidized by $135,000 from a community subscription drive,earning it a Navy contract in 1902 to build the USS Nebraska. The city fairly shook whenthe steel hull of the battleship was launched in October 1904.The long shed for the Nebraska’s construction runs through the middle of the 1901 artist’s birds-eye of the MoranBrothers Shipyard south of Charles Street, below.

Eastern investors, findingthe yard too profitable for thelocals, took it over in 1906. Itbecame the <strong>Seattle</strong> Constructionand Dry Dock Company in 1912and was sold to David Skinnerand John Eddy in 1917, partnerswho soon set construction records.By then there were twenty-eightshipyards employing about thirtyfivethousand workers. <strong>From</strong> <strong>1900</strong>to 1919, the number of workersemployed by manufacturing firmsincreased almost fivefold.ManufacturingThe 1904 launch of the battleship Nebraska, right, was the greatesttouchstone of Moran’s life as an industrialist.Table 1: Manufacturing in <strong>Seattle</strong>, <strong>1900</strong>–1919YearNumber ofmanufacturersNumberof workers1909 753 11,5231914 1,014 12,4291919 1,229 40,843This increase was caused by the overwhelming demand for ships during the war.By 1919 about seventy-five percent of the manufacturing workforce was involved inshipbuilding. Before 1910 the average proportion of the population so employed averagedabout six percent. The proportion in 1919-20 was about twelve percent. If 1914 is chosen asa more typical year and total product value is used as an indicator, we find that slaughteringand meatpacking predominated.With one dime in his pocket a 17-year-old RobertMoran was, as he later recounted, “dumped outwithout breakfast on Yesler’s wharf at 6 o’clock in themorning of November 17, 1875.” In another fourteenyears he was running both a sizeable machine shopon the waterfront and the city. Moran was <strong>Seattle</strong>’sheroic mayor during its Great Fire of 1889. Here,the self-taught mechanic-manufacturer does somefiguring at his desk.Courtesy UW Libraries, Special Collections

10 Part OneIn 1914, as table 2 shows, 1,816 workers were employed in consumer productlines, while 4,398 found work at small foundries, machine shops, lumber mills, printers,and publishers.Table 2: Major Manufacturers in 1914Type of ManufacturerTotal Product Value(in millions of dollars)Number ofWorkersSlaughterhouses and packinghouses $11.10 482Flour mills and gristmills $7.60 279Lumber mills $6.40 2,337Printers and publishers $4.60 1,057Foundries and machine shops $3.30 1,004Bakeries $2.40 534Coffee roasters and grinders $1.60 140Confectioners and ice cream makers $1.50 381Fight for Control of the WaterfrontThose interests that controlled the waterfront, the railroad companies, played acritical role in determining the city’s future. But one among them dominated: the GreatNorthern. As the builder of <strong>Seattle</strong>’s first transcontinental railroad, it sought to block outprospective entrants and to oppose construction of a common, or union, terminal. The<strong>Seattle</strong> attorney Thomas Burke became James Hill’s front man. Burke had migrated to thecity in 1875 and had become one of its most influential men by 1890, ruling the chamberof commerce and placing his proxies in city council.His nomination to the post of territorial chief justice bythe <strong>Seattle</strong> Bar Association (upon the deaths in quicksuccession of two holders of that post) was indicative ofthe esteem he attracted. Though this appointment wouldmean a big financial loss, he accepted on the conditionthat he would resign on 5 March 1889, when BenjaminHarrison would succeed President Grover Cleveland.He also headed the <strong>Seattle</strong>, Lake Shore and EasternRailroad Company, whose line was described as starting“from so many places and reaching anywhere.” One ofthe company’s key assets was its lock on thirty feet oftideland beyond the meander line (the line of high tide)over which its railroad tracks ran on pile trestles beforethe harbor lines were legally established. It was calledRailroad Avenue. The <strong>Seattle</strong> fire of 1889 destroyedThomas Burke, lawyer, with a firm gripon <strong>Seattle</strong>’s Great Northern Railroad

Fight for Control of the Waterfrontmany of these structures. Given thisopportunity, the city council decided toregrade and straighten Railroad Avenueand other streets; however, the existingfranchises complicated its job.Before the fire, Burke hadacquired a sixty-foot right-of-way onRailroad Avenue for a GN subsidiary, the<strong>Seattle</strong> and Montana Railroad. Title wastransferred to GN in 1890. By then Burkehad established himself as Hill’s “satrap,”the nickname bestowed upon Burke byhis biographer, Robert C. Nesbit. Burkesoon became Hill’s western counsel.As such, his primary function was toCourteous early-century cartoon of James Hill. obstruct any settlement that might proveunsatisfactory to Hill’s interests.Those gathered at Washington State’s constitutional convention in Olympia inJuly 1889 discussed the legal status of tideland property claims. Would the constitutionalconvention legitimize all of the squatting that had occurred during earlier decades? WhenWashington was a territory, this land was held in trust by the federal government and couldnot legally be filed upon. Nevertheless, most of the tideland had been occupied, undera variety of covers: by lieu land scrip or outright grants from the territorial legislatureand by simply driving in piles. The squatters expected the state legislature to honor theiroccupancy. The convention mandated the formation of a commission to settle these claimsand to reserve harbors and waterways for the state.11The roughly two blocks of Railroad Avenue included in this ca.1904 panorama from the Colman Building reachfrom Colman Dock on the left to the Northern Pacific Pier 3 (now Ivar’s Pier 54) on the right. The irregular line ofsheds packed along the water side of Railroad Avenue has been recently pushed further west to make more roomfor wagons between the railroad tracks and the docks. Marion Street is below the break in the warehouses, right ofcenter, and at the foot of Marion, the West <strong>Seattle</strong> Ferry dock meets the north wall of Colman Dock. On the right,the tower attached to Fire Station No. 5 at the foot of Madison Street was used for both drying hoses and as anobservation tower and office for <strong>Seattle</strong>’s Harbormaster, M. C. Jensen.

12 Part OneThe Harbor Lines Commission had to consider some important questions. Whatproportion of the tideland should be reserved for the state? And what effect would thestate’s claims have on the present occupants, including the railroad companies? Theprovision of waterways, for example, would indent the property of the present occupants.The commission wanted the state to have effective control of the harbor and waterways.How to prevent the commission from implementing this interpretation became Burke’sforemost preoccupation: he considered the state to be taking private property for public usewithout compensation. Many, however, preferred state ownership.Even the chamber of commerce’s refusal to join him in opposing the commissioncould not deter Burke. First, he sought and received an injunction from the superior courtjudge I. J. Lichtenberg in Henry Yesler’s suit against the commission—Lichtenberg owedhis appointment to Burke. The state supreme court reversed Lichtenberg’s decision sevenmonths later, in July 1891, upholding the commission by contending that the fact that Yeslerhad wharfs on the tideland did not mean that Yesler owned the land those wharfs werebuilt on. Anticipating an unfavorable decision by the Harbor Lines Commission, Burkeemployed a delaying tactic by insisting that this was a federal matter and not subject tostate jurisdiction. He filed for an injunction in federal district court, upon which sat JudgeCornelius Hanford, who also owed his appointment to Burke. Hanford dutifully issuedthe injunction, even before the briefs were filed. Meanwhile, the state attorney general,W. C. Jones, after bringing suits successively through local and state courts and winningthem all, finally filed before the U.S. Supreme Court, where Burke’s suit was waiting. On19 December 1892, the court decided against Burke because “no federal question was soraised.” But Burke’s delaying tactics worked: the Harbor Lines Commission’s terminationdate was 15 January 1893. The legislature now had to establish a second commission.The legislature enacted a bill transferring the duties of the Harbor Lines Commission toa board of land commissioners with jurisdiction overall state lands. The bill was signed by Governor JohnH. McGraw, an ally of Burke. McGraw then appointedmore compliant commissioners.The new commission laid out new harbor linesand reserved a 300-foot strip of land outside of themeander line for the harbor. The dock owners, particularlythe GN, were unsatisfied. Giving up on the commission,Burke and the GN attorneys in 1899 proceeded to workupon the new Secretary of War to reverse the priorsecretary’s approval of the commission’s action and toredraw the outer harbor line, which would eliminate the300-foot strip reserved for the harbor. Burke and theattorneys were successful: the inner harbor line becamethe official one, and the squatter rights beyond that linewere left intact. In 1903, to accommodate the GN (andnegotiated at Burke’s urging through Hill’s legislativelobbyist James D. Farrell), the harbor lines were furtherextended at Smith Cove.A portrait of Eugene Semple engravedduring his tenure as governor ofWashington Territory, 1887-1889.

Fight for Control of the WaterfrontTwo other critical problems impinged upon waterfront development. One problemwas the city’s hilly terrain, the other the need to connect Lake Washington to the sound ateither Elliott Bay or Shilshole Bay. To connect the lake to Elliott Bay, a trench could be dugthrough Beacon Hill; the displaced earth could be dumped onto the tidal flats, which thencould be developed for industrial and commercial use. Or the connection could be made bydigging a canal from Lake Washington to Lake Union, from Lake Union to Salmon Bay,and from Salmon Bay to either Smith Cove on Elliott Bay or Shilshole Bay. This optionwould require a lock to equalize the water level between the Sound and the lakes.Before 1890 several civic leaders favored the canal from Lake Washington toShilshole Bay. Among these leaders were <strong>Seattle</strong>’s founding father, Arthur A. Denny;Governor McGraw; Thomas Burke; and Burke’s father-in-law, John J. McGilvra. Such acanal would enable them to build a steel mill in Kirkland and would provide a route forfloating log rafts and transporting coal from the east side of Lake Washington. Burke’s<strong>Seattle</strong>, Lake Shore and Eastern Railroad had been built in part to transport some of thesecommodities. However, in 1893 Eugene Semple, a former Washington Territory governor13Eugene Semple’s earliest dredging and tidelands reclamation work (1895-97) is revealed in Andres Wilse’s 1898panorama from Beacon Hill. First Avenue extends south (from the right) into the center of the scene on madeland, which replaced a timber trestle. The industrial clutter of the tidelands south of King Street includes othersmaller fill sites, left and right, as well as the great wooden “wall” of the Northern Pacific railroad trestle and itswarehouses that curves from the base of Beacon Hill through the center of the scene to the central waterfront.

14 Part OneCourtesy of Special Collections,University of Washington LibrariesSouth Canal contributions to the tideflats spew fromEugene Semple’s flumes.who promoted a south route throughBeacon Hill, had secured passage ofa bill allowing private companies toconstruct public waterways across stateownedproperty and to charge lienson reclaimed tideland that was sold tofinance the work. Governor McGraw hadblindly signed the bill, not realizing itfavored the Beacon Hill route. Not untilSemple filed plans with the WashingtonState Lands Commission for a competingland scheme did the implications becomeapparent to McGraw.With the blessing of the chamber of commerce, Semple lined up his financialbackers. A mass meeting of four thousand, headed by the mayor, brought in $500,000 insubscriptions. The <strong>Seattle</strong> Post-Intelligencer (P-I) hailed the event as “one of the greatepochs in the history of <strong>Seattle</strong>.” Work began on 29 July 1895. By May 1896 almost onehundred acres of the tidal flats had been filled, most of it with mud dredged and drainedduring the building of the East Waterway. Sales of the newly created waterfront kept pacewith this earthmoving activity. Burke and the GN, fearing that Semple would succeed ingetting federal funds at the expense of their north canal route, filed an injunction whilechallenging the constitutionality of the 1893 law. For eighteen months Semple’s canalproject was halted while the state supreme court decided the case.Although the law’s constitutionality was upheld, Semple experienced severefinancial difficulties, even losing the backing of his St. Louis nephews Edgar and HenryAmes. (Edgar would later reap immense profits in shipbuilding at Harbor Island duringthe Great War.) Over Burke’s protests Semple reorganized his firm, the <strong>Seattle</strong> and LakeWashington Waterway Company,and got a four-year extension ofhis contract to fill the tidal flats.Burke, while failing to get a billthrough the legislature terminatingthe south canal project, did getan injunction preventing anyrailroad-owned tideland west ofthe dead end of Hanford Streetfrom being filled in. And whilethe injunction was in effect,Burke and his allies gatheredenough financial support to diga ten-foot-deep channel betweenShilshole and Salmon baysand received approval from thechamber of commerce to lowerCourtesy of Special Collections, University of Washington LibrariesSome of the trestlework used for the distribution of dirt onto thetideflats during the attempts at digging a “south canal” to LakeWashington. A portion of the Rainier Brewery is evident on thefar right.

Fight for Control of the WaterfrontLake Washington’s water level. Burke then negotiated the termination of the injunction,effective May 1901. The public’s patience with Semple’s project was growing thin and waslost altogether when officials discovered that all the water that Semple had been using tosluice away Beacon Hill was being sold to him at what seemed suspiciously cheap rates.The scent of corruption spread.The chamber of commerce then sent the editor of the P-I, Erastus Brainerd, in January1902 to Washington, D.C. Brainerd had earned the respect of the business community forhis key role in publicizing the city’s indispensable connection to Alaska for gold seekersand the wider economic benefits that would follow the gold rush. He was credited also withestablishing the U.S. Assay Office 14 in <strong>Seattle</strong>. Brainerd was to lobby for appropriationsfor a north canal. Semple followed Brainerd to the nation’s capital to voice his opposition,and then Burke decided to go as well to support Brainerd at the hearings. Burke carried theday by falsely informing the congressional committee that the law authorizing the southcanal had been declared unconstitutional by the state supreme court. Burke, accustomedto intoning righteously, convinced the committee of his truthfulness. Its authorization of$160,000 for the north canal doomed Semple.Closing in for the kill, Burke boasted to the GN’s general manager, John F. Stevens,in September 1902 that he could buy Semple out for a mere $6,000. Doing so, he said, would“prevent the disordering of the waterway across our tide lands on the South of our terminalgrounds . . . and this at a cost to the three railway companies that would be a bagatelle incomparison with the advantages to be gained.” Stevens spoke to Hill immediately and thentelegraphed Burke: “Close at once for control <strong>Seattle</strong> Lake Washington waterway per yourmessage ninth.”Semple had nevertheless almost completed the East Waterway at the mouth ofthe Duwamish River, and work on the West Waterway had begun in August 1903, pavingthe way for the later development of Harbor Island. However, the demand for reclaimedtidal flats outstripped Semple’s financial resources, forcing him to pledge future revenueto secure credit to continuethe reclamation work. In theprocess he surrendered most ofhis stock and ultimately controlof his reclamation project. Newmanagement stopped work onthe south canal, concentratinginstead on filling in the tidal flats.The railroads filled in their ownlands. A grand jury investigationinto the suspicious water contractled to the City issuing a stop-workCourtesy of Special Collections, University of Washington LibrariesWhile Eugene Semple filled a few acres on the tideflats with thediggings from his canal, he also left this scar. The ca. 1902 viewlooks west through what is now S. Columbia Way where it descendsin a curve from Beacon Hill to connect with both Interstate 5 andthe Spokane Street Viaduct.15order on Semple’s canal in May1904. The area around BeaconHill became <strong>Seattle</strong>’s industrialheartland. And the railroadsreaped revenue from servicing

16 Part OneCourtesy, The Rainier ClubErastus Brainerd from the RainierClub’s “mug book” of members.grain elevators, flour mills, steel plants, coal docks, toolmakingand machinery plants, and shipyards that locatedthere during the first two decades of the century.Topping off this revenue were the City’s landgrants to the GN and NP in exchange for their promises tobuild a union depot. These critically placed landholdings,adjacent to or near the railroad tracks, allowed the Hillinterests to negotiate tie-in contracts with shippers andwarehouse operators as a condition of sale of theseproperties. <strong>From</strong> its dominant position on the waterfront,the GN also controlled wharfage rates, threatening anycompetitor who charged or might charge rates lower thanthe GN did. The GN’s abuse of this power eventually ledeven the chamber of commerce in 1911 to join publicownership forces in opposing the railroad companies’domination of the waterfront by supporting legislationfor the establishment of port districts. It took the smell ofanticipated profits to be made from the opening of the Panama Canal to turn these railwaysupporters into opponents. How this conflict played out will be covered later in relation tothe Harbor Island–Bogue Plan controversy.It should be noted that it was common for railroads to demonstrate politicalpower during this period. In league with timber interests, railroad companies dominatedthe politics of Wisconsin and Minnesota. The GN and NP (both controlled by Hill) aloneheld power in the Dakotas, and they joined with the mining interests to control politics inMontana and Idaho. The Southern Pacific dominated California’s politics and directed itseconomy, especially in Southern California. In Oregon the locally owned Oregon SteamNavigation Company gained control of Columbia River traffic in the 1860s. And after thetransportation magnate Ben Holladay gained control of coastal traffic with his Pacific MailLine, he established the Oregon and California Railroad and dominated river traffic onIn 1898 the U.S. Assay Officemoved into a two-story cast-ironand masonry building on First Hill,built in 1886 by Post-Intelligencerowner Thomas Prosch for officesand a ballroom. It was the job of theAssay Office employees, posinghere, to determine a fair price forthe gold and silver brought through<strong>Seattle</strong> by miners so that the U.S.Government might purchase it.After the Assay Office moved tothe new Immigration Building in1932 this, its first <strong>Seattle</strong> home at619 Ninth Avenue, was renovatedinto the German House.

Fight for Control of the Waterfrontthe Willamette River. Holladay’s domination of both Oregon transportation and Oregonpolitics ended with the collapse of his financial empire in 1873, though the transportationnetwork that he established was extended later by others.That railroads became prime targets first of the Grangers, then the Populists,and finally the Progressives of the early twentieth century is not surprising. The railroadcompanies, allied with the business elite of whatever communities their lines passedthrough, stood in the way of substantially all political reform. Passage of the Hepburn Actin 1906 finally gave the Interstate Commerce Commission the regulatory authority overrailway practices that it had previously lacked.As to the GN and NP, together they purchased the Burlington Railroad system in1901 in order to secure a connection to the Chicago hub and to stabilize the transcontinentalrail business along the northern tier. Known as the Northern Securities Company, thismonopoly could charge whatever rates the traffic would bear; its stock was consideredby the U.S. Attorney General Philander Knox to be thirty percent water. This monopolywas but a climax to the railroad reorganizations that the J. P. Morgan interests, in alliancewith Hill, had been involved in since 1896, when the NP drifted into receivership. StuartDaggett, in his classic study on these reorganizations, notes that the NP was dominated bythe Morgan-Hill interests since that time.17Anders Wilse’s 1898 view of the tideflats may be compared to this 1914 record of the same neighborhood. Here,sixteen years later, both Fourth and Sixth Avenues cross the new industrial district, although temporarily ontrestles. The view from Beacon Hill looks due west to Robert Moran’s former shipyard. The long shed fromwhich the Nebraska was launched ten years earlier is profiled against Elliott Bay. Above it, the popular Luna Parksprawls above the tidelands off of Duwamish head. The Centennial Mill, one of the early opportunists on thetideflats, is included on the far left.

18 Part OneProsecuted under the Sherman Antitrust Act, the Northern Securities Company wasordered dissolved by the federal court; the decision was later upheld by the U.S. SupremeCourt. However, during this period, Hill, while excluding Edward Henry Harriman’s UnionPacific from the Northern Securities deal, agreed with Harriman to respect the monopoly ofeach in the Pacific Northwest: Union Pacific would not enter Washington, and Hill’s lineswould not enter Oregon. Hill’s virtual monopoly in Washington led to the Pacific CoastLumber Manufacturers’ Association charging the GN with restraint of trade before theInterstate Commerce Commission in 1907. Not all was harmonious among the businesselite—many businesses considered freight and wharfage rates to be discriminatorilyexorbitant. Occasionally they would ally against the railroad companies, seeking to havethem regulated through state railroad commissions. Such a commission was not legislatedin Washington until a GN partisan, Albert E. Mead, was elected governor in 1904. Meadthen appointed a compliant commission subservient to railroad interests.Seeding of the Municipal Ownership Movement<strong>Seattle</strong>’s hills impeded commercial and industrial development. And as the 1889fire demonstrated, the city needed a permanent and dependable water supply. Reginald H.Thomson, who served as city engineer from 1892 to 1911, tackled both of these issues.Thomson preferred municipal ownership of utilities. He also planned to connect thedowntown with sections of the city that its hills segregated. Downtown <strong>Seattle</strong> neededlinkage with outlying areas: Interbay, Ballard, and the Lake Union basin to the north; RainierValley to the southeast; and the tideland to the south. Thomson opposed the erection of anypermanent structures in the way of these planned linkages and successfully prevented thecity council from granting a franchise to the GN when that would have blocked First AvenueSouth and closed streets leading south between First and Fifth avenues. He convinced Hillto tunnel under that section instead.Harry Chadwick, publisher of the weekly Argus, viewed Thomson, however, assubservient to Hill, charging that he gave Hill tunnel rights without specifying a route; thathe helped Hill oppose the NP’s earlier attempts to enter the city; and that he obstructedthe NP’s efforts to gain unrestricted access to its own docks. Chadwick also charged thatThomson was instrumental in the city council’s granting of franchises in exchange forunfulfilled promises to build a decent depot and that he hampered the council in its effortsto establish a union depot. Even the chamber of commerce complained about the GN’smiserable depot facility, an “embarrassment” to a city of almost one hundred thousand. Notuntil 1906 would the city finally get its long-sought union depot, the King Street Station,which was rivaled five years later by E. H. Harriman’s Union Station, barely one city blockaway.Thomson constructed Westlake Avenue to connect the downtown with the LakeUnion basin, cut Dearborn Avenue through the north end of Beacon Hill to link the downtownwith Rainier Valley, and laid out Magnolia Way to connect the downtown with Interbayand Ballard. The downtown itself underwent continual regrading, though not withouteditorial outcry. Harry Chadwick complained regularly about the contractors’ prolonged

Seeding of the Municipal Ownership Movementabandonment of work while citizens suffered through the dust and dirt of summers only toslog through muck and mud in the rainy seasons. Chadwick suspected that a contractors’combine was the cause. Colonel Alden J. Blethen, publisher of The <strong>Seattle</strong> Times, feudedcontinuously with Thomson, as he did with other advocates of moral reform and publicownership of utilities.In laying out his plans for the City’s control of its water supply, Thomson expandedupon the ideas of his predecessor, Frederick H. Whitworth. Whitworth saw the Cedar Riverwatershed as the key to <strong>Seattle</strong>’s development, believing it an ideal source of water fordrinking, firefighting, flushing sewage, and generating hydroelectric power. Though thelast was considered possible at the time, it remained subordinate to the other needs untilafter the turn of the century. The United States was only beginning to use electric powerin the 1890s. An examination of this early use provides the context for one of the titanicpolitical struggles of early twentieth-century <strong>Seattle</strong>: private versus public ownership ofutilities.David E. Nye, in hisbook on electrification in theUnited States, points out that before1910 electrification had beenkeyed to commercial and industrialusers, not domestic users.Most homes had not been wired:only one in seven homes had electricityby 1910. Commercial andstreet lighting consumed most ofthe investment capital, as a warypeople were being introducedto the wonders of electricity. By<strong>1900</strong> street railways had becomeelectrified across the country.Many of these lines became un-19City Engineer R. H. Thomson is both picturedand characterized in Frank Calvert’s 1911book, The Cartoon, A Reference book of<strong>Seattle</strong>’s Successful Men With Decorationsby the <strong>Seattle</strong> Cartoonist’s Club. While thephotograph is not credited, the artist whogot the Thomson assignment was John Ross“Dok” Hager, a dentist turned cartoonist.Beginning in 1909, Dok’s cartoon take-offson the eccentric Robert W. Patten, <strong>Seattle</strong>’seccentric “Umbrella Man,” was a regularand popular feature in The <strong>Seattle</strong> Times.Turning his hand this time to the formidableThomson, “Dok” has the city engineerrolling up his right sleeve for a little “handywork” on the disrespectful satirist himself.To the side is a photograph of the “UmbrellaMan” himself.

20 Part Oneprofitable as they were extended to serve the outlying communities being promoted bydevelopers. <strong>Seattle</strong>’s expansion outward was but a lesser version of the extreme real-estatepromotions in Southern California. Mergers of the weaker with the stronger street railwaysbecame common in <strong>Seattle</strong> and other cities.As elsewhere, when <strong>Seattle</strong> developers subdivided properties to sell lots they neededto guarantee access to downtown. Street railway companies had to be induced to build linesto the suburbs. When they did the ridership moreoften than not proved too little to pay expenses,and the firms passed into receivership. Morethan a dozen of these independent lines operatedunder city franchises in the 1890s. During theDepression most used capital that was supposedto be reserved for maintenance to operate. Thispractice led to the deterioration of what werealready poorly constructed trolley systems. Inthis setting the Stone and Webster ManagementCorporation of Boston had the banker JacobFurth apply in 1899 for a forty-year franchise toconsolidate four such streetcar lines. Stone andWebster was representing two eastern investmentfirms: Lee, Higginson and Company and Kidder,Peabody and Company. The firm also heldGeneral Electric securities issued earlier by thefour companies to pay for equipment they hadpurchased. On 12 May 1899 the companiessigned escrow deeds.On 9 March <strong>1900</strong>, a blanket forty-yearfranchise was granted to Furth and his partner,J. D. Lowman. However, a citizens’ group, theCommittee of 100, led by James Allen Smith ofthe University of Washington, argued successfullyto shorten the life of the franchise to thirty-fiveyears, to make the new firm provide free transfersto riders, and to allow riders the option of buyingtickets in lots of one hundred or more at a twenty-Most of the community of squatters that held to the bluff andbeach below Denny Hill since the early 1890s were evicted forthe opening of the north portal to the railroad tunnel boredbeneath the central business district. The work began on AprilFools Day, 1903, when cannons shooting Cedar River waterfrom the municipal system first attacked the bank. The rocksthat could not be carried away on the flood were blasted. Anestimated 500 thousand cubic yards of dirt was removed fromthe tunnel by a crew that sometimes numbered 1,000, and muchof the dirt was used as fill along the waterfront, although thistime not for squatters.

Top: The first railroad depot at the foot ofColumbia Street was quickly rebuilt followingthe “Great Fire of 1889.” With additions thenew station eventually stretched nearly as farsouth as Yesler Way, and it is from Yesler thatit is seen here. This inelegant station wasan embarrassment to <strong>Seattle</strong>’s cosmopolitanambitions. Coaches on passenger trains wouldregularly unload visitors onto the splinteredplanks and puddles of Railroad Avenue blocksaway from the depot. After sunset the poorlylighted waterfront was a hazard for anyone andespecially for unprepared visitors.Bottom: First the King Street Station in1906 and five years later the Union Pacific’sWashington-Oregon Depot one block to theeast on Jackson Street twice fulfilled localsexpectations for a grand transportation temple.In this view Harriman’s Union Depot is on theleft and James Hill’s King Street station with itsVenetian tower is to the right.Westlake Avenue was cut throughfrom Pike Street and Fourth Avenuein 1906, repeating a connection madethirty-five years earlier by a narrowgaugedrailroad that through most ofthe 1870s delivered coal from scowson Lake Union to the Pike Street CoalWharf. This view dates from 1909when Fourth Avenue, on the left, stillclimbed Denny Hill, but for less thantwo years more. By 1911 the modesthill’s Fourth Avenue “summit” nearBlanchard Street would be loweredeighty-five feet with the DennyRegrade.21five percent discount. In addition, the councilwas persuaded to regulate fares and to establishminimum-wage scales. The new firm was namedthe <strong>Seattle</strong> Electric Company (SEC) until 1912,when it became the Puget Sound Traction, Powerand Light Company. Thomas Burke, Furth, andfour other prominent citizens were on the SEC’sboard of directors.If there was an improvement in service,the Argus did not recognize it. Suspectingcollusion between the council and the SEC,Chadwick claimed, “The whole system is rottento the core . . . [and needs] complete revision.”Overcrowding, erratic service, and open cars,even in winter, were still typical. “This is notwhat the <strong>Seattle</strong> Electric Company promisedwhen they were given their present franchise,”Chadwick declared. When the company wasgranted an exclusive franchise over the Westlakeroute in 1905, north-end community organizationscomplained so loudly that a common-user clausewas inserted into the agreement. Charges offavoritism were raised again that year whenthe council loaded down the franchise terms soheavily for the developer James A. Moore, whohad applied for a street railway franchise, that hebacked out. Notice should be taken of these northendorganizations. They were operated primarilyby middle-class women and would soon form analliance as the North End Federated Clubs. Thisgroup became one of the main components ofthe municipal ownership coalition. Among itsCourtesy, Old <strong>Seattle</strong> Paperworks

22 Part Oneleadership were two women who wouldgain elective office during the <strong>1920</strong>s:Bertha Knight Landes would be electedto the city council and the mayorship,Kathryn Miracle to the council.Turning to the generation anddistribution of electric power, we learnmore about how the public came tofavor municipal ownership of electricalutilities. The state supreme court set thestage when it ruled in 1895 (Winston v.Spokane) that a city could issue revenuebonds that were to be exclusive of generalobligation bonds. After this decision,the city council passed a new waterordinance, which the mayor vetoed. Thecouncil then submitted a $1.25 millionThe carving of no other <strong>Seattle</strong> regrade is so evident.The 108-foot deep notch at Dearborn Street was cutwith the daily blast of six million gallons of water. Thehydraulics began in the fall of 1909 and ended three yearslater and the Twelfth Avenue South Bridge opened in thefall of 1912. The Dearborn Cut converted more than amillion yards of glacial hardpan into mud that was thendistributed on the tideflats and sold by Ralph Dearborn,namesake for both the regrade and the street.water bond issue to the voters in December, which they approved 2,656 to 1,665. Next thecouncil successfully lobbied the 1897 legislature for the authority to issue revenue bondsjust as the economy was rebounding at the onset of the Yukon gold rush, which improvedthe marketability of the bonds.The Snoqualmie Falls Power Company applied for an electrical franchise in 1898,but the council imposed terms on the franchise that the company judged would inhibit bondsales. Enter the Washington Power and Transmission Company, whose engineers wereCharles Stone and Edwin Webster. This company had purchased land at Cedar Lake from the<strong>Seattle</strong> Electric Company— land that was strategically located for power development. Toprevent the city from contracting with the Washington Power and Transmission Company,the Snoqualmie Falls Power Company enjoined the city. In August 1899, R. H. Thomsonrecommended that <strong>Seattle</strong> acquire Cedar Lake; a resolution was passed, followed by anordinance on 31 January <strong>1900</strong> forcing the Washington Power and Transmission Companyto sell its lands to the city or face condemnation proceedings and the exercise of the rightof eminent domain.As completion of the Cedar River dam approached,even the chamber of commerce alleged that a city-owned plantcould provide cheaper electricity than the SEC. The <strong>Seattle</strong>Manufacturers’ Association, established in <strong>1900</strong> to promotelocal industry and to combat unions, urged the city to get intothe power business in order to drive down electric rates and toextend and improve services. In hopes of breaking up the SEC’smonopoly, the Municipal Ownership League was organized inThis caricature of Jacob Furth appeared first in the Argus and later in a collectionof Argus cartoons titled, Men Behind the <strong>Seattle</strong> Spirit. Showing flip or having funwith the “Mighty Furth” the book’s own caption reads, in part, “President of the<strong>Seattle</strong> Electric Co., president of the Puget Sound National Bank, and president ofa lot of other things.”

Seeding of the Municipal Ownership MovementCourtesy, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections.preparation for the 1902 city election. The league got a proposition on the ballot that wouldauthorize the construction of a generating plant at Cedar Falls. The Argus claimed, “Nomore important question is to come before the people . . . than that of a municipal lightingplant (Yesler Substation)”. The proposition won overwhelmingly, by 6,697 votes.Thomson, however, felt the sting of Chadwick’s lash over a series of transactionsbefore construction of the plant was completed in 1905. Chadwick taunted Thomson fortardiness in conducting preliminary surveys, for not indicating that more than street lightingwould be provided, and even more bitingly for awarding the electrical equipment contractto General Electric, despite a lower bid from an established local manufacturer. Chadwickaccused Thomson of “working hand in glove” with Stone and Webster, which had ties toGeneral Electric, as noted earlier.Seeing the handwriting on the wall, the SEC dropped its electric rates in October1904 from twenty cents to twelve cents per kilowatt-hour. This still fell short of the city’sprospective residential rate of eight cents per kilowatt-hour. The SEC steadily lost customersto the city: 197 from October toDecember 1906 and 233 fromJanuary to May 1907. CityLight was up and running, andit continued to set the yardstickfor electrical rates for the nexthalf century. Nevertheless, theSEC and its successors manageduntil <strong>1920</strong> to retain sixty-five toseventy-five percent of its powercustomers and its private powerallies in the downtown businessarea.Faced with a nationwidemovement against absenteeownership, the trade association23Here are some of the urbane fruitsof the gold rush. The scene looksnorth on First Avenue towards itsbusy intersection with MadisonStreet. The three elegant andnearly new buildings on the left,historically the Globe and Beebebuildings and the Hotel Cecil, areall 1901 creations of the architectMax Umbrecht. A cable car onMadison Street heads throughthe intersection and beyond it arethree <strong>Seattle</strong> Electric Companytrolleys and a few wagons. At thistime the motorcar in <strong>Seattle</strong> wasstill a rarity. Ordinarily one eitherwalked or took a trolley.Ed Duffy, the young electrical engineer who helped J.D. Ross wirethe city’s first generator, made this early photograph of City Light’stimber crib dam on the Cedar River.

24 Part Oneof the industry, the National Electric Light Association(NELA), began lobbying for the establishment of stateregulatory commissions to prevent municipalities fromconstructing their own electrical plants and distributionsystems. Douglas Anderson, in his Regulatory Politicsand Electric Utilities, convincingly documents NELA’scampaign to make state regulation the alternative tomunicipal ownership. By 1904 the Chicago utilitiesmagnate Samuel Insull was able to convince a majorityof NELA members of the wisdom of this tactic. NELA’sbasic tenet was as follows: “Public regulation andcontrol, if efficient, removes the necessity or excuse formunicipal ownership. . . . If public regulation shall fail toestablish good understanding between the corporationsoperating public utilities and the customers of thosecorporations, we shall inevitably have a revival of thecry for municipal ownership.”If any ambiguity remained, NELA cleared theair: “If state commissions be constituted, they shouldbe appointed in that manner which will give them thegreatest freedom from local and political influences.”<strong>From</strong> generators beside the CedarRiver the City Light current traveledforty miles to the municipally ownedutility’s first distribution station atSeventh Avenue and Yesler Way. At45,000 volts the operation set a recordwith its transmission voltage.Key to eliminating municipal competition would be the enactment of a certificate-ofnecessitylaw. Under such a law, any municipality that chose to erect its own electric plantwould have to demonstrate to the regulatory agency that a necessity for one existed. If theregulatory body were properly under control, as noted in NELA’s protocol, certificationwould be denied. When the Washington State Railroad Commission was expanded to coverutilities in 1911, becoming the Washington State Public Service Commission, municipallyowned utilities were exempted from its jurisdiction, to the dismay of the private utilities.Consequently, the private utilities repeatedly sought legislation requiring certificates ofnecessity; when they won this legislation, the voters rejected it by referendum, as we shallsee, in 1916 and in 1922.Industrial RelationsIndustrial relations were also transformed during these early years. The variousbusinesses already referred to necessarily had to employ workers. How the firms paid themand under what conditions they were to work affected profits. Ideally, businesses would getmaximum productivity at the lowest possible cost. How a business achieved this dependedheavily on its negotiations with its employees. If it could set the terms of employment bybargaining with each employee individually the firm had maximum advantage, particularlyif the skill being sought was in abundance. This advantage would sometimes lead todictatorial control of the workplace, sometimes to a benevolent paternalism, and sometimesto some other accommodation. If the employees joined together in a union, the firm would

Industrial Relations 25have to bargain with that collective entity. Which side would have the advantage dependedon each side’s relative strengths and the labor market.During the first two decades of the century, industrial relations in <strong>Seattle</strong> werecolored by the struggle between employers and unions. The employers aimed for the openshop (an establishment in which union membership is not a condition of employment),and the unions sought the closed shop (in which union membership was a condition ofemployment). The unions hoped to achieve the closed shop first by being recognized bythe employers as the bargaining agent. To gain this recognition unions usually staged astrike, and the employers just as often applied to the courts for an injunction prohibiting thestrike, which was usually granted. When labor was in short supply and employers neededworkers, unions were usually recognized as the bargaining agent without a strike.Before focusing on <strong>Seattle</strong>, we should review the status of industrial relations ingeneral at the turn of the century. After the Civil War, a “second American revolution” wasunleashed as industrialization progressed free of the political hindrances imposed by theslave states of the antebellum period. Prevented by the southern states from being charteredbefore the war, the transcontinental railroads were finally freed during the war, beginningwith land grants to the Union Pacific in 1862 and the Northern Pacific in 1864. Otherregional roads also received land grants. The grant to the Texas and Pacific in March 1871was the last given to a trans-Mississippi road. A total of more than 180 million acres of landpassed into railroad hands, of which more than 100 million acres were finally sold. (Forcomparison, Washington State covers 68,126 square miles or 43,600,640 acres.)Railroad construction proved the catalyst for industrial expansion after the war,as the automotive industry would in the <strong>1920</strong>s. The steel industry, marked by crucialtechnological changes, responded to these market demands, as did machine tooling, coalmining, and ancillary industries. The electrical industry took off in the 1880s with GeneralElectric and Westinghouse absorbing smaller firms along with their patents, a processthat eventually brought the two firms together in 1895 in a patent pool—a duopoly. Theunprecedented demand for capital to finance this growth brought the modern corporationinto full flower, as it did banking houses on Wall Street and Boston’s State Street, whereStone and Webster had its headquarters. Absentee ownership came to characterize largescalebusiness operations. Corporations in the same field often combined to control pricesand production, to limit competition as much as possible, and to counter union organizingby shifting production from a troubled plant to an untroubled one and by sharing lists oftroublesome employees—blacklists. In <strong>Seattle</strong> the Great Northern and the <strong>Seattle</strong> ElectricCompany were the most prominent corporations. The latter company became commonlyknown as the Boston Syndicate because it was owned by the Boston-based Stone andWebster. To many citizens such businesses seemed less concerned about the publicwelfare than locally owned firms. Newcomers, arriving with high expectations, joined theopponents of absentee ownership. The nucleus of the reform movement was created bythese conditions.The general status of industrial relations in <strong>Seattle</strong> at the century’s beginning wascharacterized by the state labor commissioner, William Blackman, at a 1903 chamber ofcommerce gathering to celebrate the city’s birthday:

26 Part One[N]ow all the trades are organized and a large percentage of workingmen and women are within the ranks. Today <strong>Seattle</strong> has about seventyfivedifferent labor organizations, with a membership of between six andseven thousand. . . . The workers, through their organizations, advocateshortening the hours of labor so that they may improve their minds inkeeping with the progress of the age. They are striving in turn to save fromtheir earnings something for a home. Statistics gathered by the State LaborBureau show that two-sixths of the wage earners own their own homes.This being the condition, such citizens must be given credit for being afactor in the community. The workers are taking an interest in legislation.. . . They are interested in passing good laws for the upbuilding of ourgovernment and the preservation of the home. They have learned that thestrike and boycott are fast growing to be a thing of the past.In this statement we note the upward mobility of wage earners, their desire foreducation, their growing interest in social reform legislation, and the ameliorative roleat this time of the chamber of commerce. The neutral position of the chamber on theopen shop–closed shop issue was indicated in 1904,when the <strong>Seattle</strong> Manufacturers’ Association invitedthe organization to join its Citizens’ Alliance to combatunionization. The chamber responded by recommendingcreation of a sixty-member congress: thirty membersrepresenting labor unions and thirty representing theemployers. The resolution was tabled, but the chambermoved gradually into the open shop camp by 1914.When William Pigott opened his <strong>Seattle</strong> Steel rolling mill in 1905 theRailway and Marine News called it “the beginning of a new industrialepoch.” Within the year The <strong>Seattle</strong> Times named it “<strong>Seattle</strong>’s LittlePittsburgh.” Instead, Pigott borrowed the name of another Ohio steeltown for this neighborhood between Pigeon Point and West <strong>Seattle</strong>. Hecalled it Youngstown. By 1910, a likely date for this view of his mill,Pigott was regularly called “<strong>Seattle</strong>’s greatest industrialist.” After hisdeath in 1929, the plant was sold to Bethlehem Steel and much later,in 1991, Birmingham Steel acquired what survives as the region’s laststeel mill.Courtesy, Bill Burden

Industrial RelationsThe “strike and boycott,” however, were coming more fully into play; theseactions were the only means left for organized labor to combat the open shop drive of manyemployers once negotiations and mediation had failed. Before the American Federation ofLabor (AFL) penetrated the region in 1902, another federation, the Western Central LaborUnion, represented individual unions. It had been formed from the remnants of the Knightsof Labor and several small miner and maritime unions. Like the AFL the Western CentralLabor union was oriented to lobbying, assisting its craft members in bargaining whencalled upon, gaining the cooperation of other unions in sympathy strikes, and organizingboycotts. It also settled disputes between unions that might lay claim to the same craft, asoccurred in a 1902 maritime strike in which the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific contested thejurisdiction of the International Longshoremen’s Association. This kind of jurisdictionaldispute was less apt to happen when unions were organized on an industry-wide basis, aswere the steel and automobile industries in the 1930s. In these industries, several craftswere represented by a single elected bargaining agent.When the Populist platform of 1897 failed to be enacted, the Western Central LaborUnion joined other organizations to form the State Labor Congress. Soon the congressdecided it needed a voice to justify unions to the public and to report stories that the othernewspapers neglected to print—stories of special relevance to working people that wereobjectively reported. It started the <strong>Seattle</strong> Union Record, a weekly, in <strong>1900</strong>.The establishment of the Socialist Party of Washington in <strong>1900</strong> was an additionalindicator of labor unrest and of the perceived need for social and political reform. HarryAult, publisher of the Union Record, was himself an outspokenSocialist. Given the economic revival, the time seemed ripe toset up a broader labor organization. So inspired, the State LaborCongress founded the Washington State Federation of Labor in1902, affiliating it with the AFL. To prepare for the 1903 legislativesession, the federation joined with the Washington State Grange,middle-class reformers, clergymen dedicated to social causes,and the Washington Federation of Women’s Clubs. Together theywon passage of several pieces of reform legislation: a child laborlaw, an eight-hour day statute for employees working on publicprojects, and an initiative law.Highlighting labor unrest at the time of the legislativesession was a 162-day maritime strike against the Pacific CoastSteamship Company over overtime pay. The strike ended with thedefeat of the longshoremen in February 1903. Violence had flaredup when strikebreakers were brought inand housed and fed on a steamer drawnup dockside. In March the <strong>Seattle</strong> ElectricCompany announced a wage cut forits streetcar employees, who were paidtwenty cents an hour and worked ten anda half hours a day, seven days a week,with time off if requested in advance.27Courtesy,University of WashingtonLibraries, Special Collections.Harry Ault, publisher of the<strong>Seattle</strong> Union RecordIn 1918 the <strong>Seattle</strong> Union Record became a daily and wasthe first daily labor newspaper in the nation.