10 top tips for PCT Boards - Centre for Mental Health

10 top tips for PCT Boards - Centre for Mental Health 10 top tips for PCT Boards - Centre for Mental Health

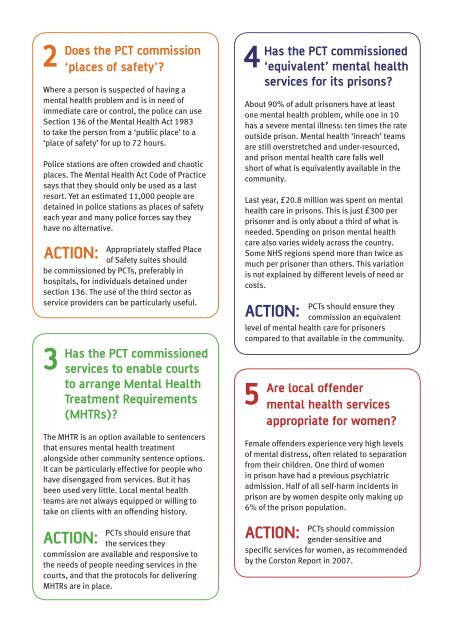

2Does the PCT commission‘places of safety’?Where a person is suspected of having amental health problem and is in need ofimmediate care or control, the police can useSection 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983to take the person from a ‘public place’ to a‘place of safety’ for up to 72 hours.Police stations are often crowded and chaoticplaces. The Mental Health Act Code of Practicesays that they should only be used as a lastresort. Yet an estimated 11,000 people aredetained in police stations as places of safetyeach year and many police forces say theyhave no alternative.Action:Appropriately staffed Placeof Safety suites shouldbe commissioned by PCTs, preferably inhospitals, for individuals detained undersection 136. The use of the third sector asservice providers can be particularly useful.3Has the PCT commissionedservices to enable courtsto arrange Mental HealthTreatment Requirements(MHTRs)?The MHTR is an option available to sentencersthat ensures mental health treatmentalongside other community sentence options.It can be particularly effective for people whohave disengaged from services. But it hasbeen used very little. Local mental healthteams are not always equipped or willing totake on clients with an offending history.Action:PCTs should ensure thatthe services theycommission are available and responsive tothe needs of people needing services in thecourts, and that the protocols for deliveringMHTRs are in place.4Has the PCT commissioned‘equivalent’ mental healthservices for its prisons?About 90% of adult prisoners have at leastone mental health problem, while one in 10has a severe mental illness: ten times the rateoutside prison. Mental health ‘inreach’ teamsare still overstretched and under-resourced,and prison mental health care falls wellshort of what is equivalently available in thecommunity.Last year, £20.8 million was spent on mentalhealth care in prisons. This is just £300 perprisoner and is only about a third of what isneeded. Spending on prison mental healthcare also varies widely across the country.Some NHS regions spend more than twice asmuch per prisoner than others. This variationis not explained by different levels of need orcosts.Action:PCTs should ensure theycommission an equivalentlevel of mental health care for prisonerscompared to that available in the community.5Are local offendermental health servicesappropriate for women?Female offenders experience very high levelsof mental distress, often related to separationfrom their children. One third of womenin prison have had a previous psychiatricadmission. Half of all self-harm incidents inprison are by women despite only making up6% of the prison population.Action:PCTs should commissiongender-sensitive andspecific services for women, as recommendedby the Corston Report in 2007.

6 8Are local offender mentalhealth services sensitiveto the needs ofBME groups?People from many Black and minorityethnic (BME) backgrounds are greatly overrepresentedin acute psychiatric wards, securehospitals and custody. But they are less likelyto be referred for psychological therapiesor early interventions. This prompted theGovernment’s Delivering Race Equality (DRE)action plan in 2005.Action:PCTs need to commissionculturally sensitive andspecific services for BME groups. Somevoluntary sector provision might be betterequipped to meet these needs.7Has the PCT commissionedan appropriate number ofsecure hospital beds?A vast amount is currently spent on forensicmental health services, which play animportant part in the diversion process.Forensic services provide secure detentionin NHS-funded beds when prison isinappropriate.There are nearly 4,000 people in forensicservices (an average of just over 25 per PCT).In addition, the number of people newlytransferred from prison or courts into forensicservices is increasing every year.Action:At a cost of more than£150,000 per bed per year,forensic services put a great deal of pressureon PCT budgets. It is therefore essential that‘step-down’ and low security services are alsocommissioned for patients to move on to,when suitable, at a lower cost.Has the PCT commissionedmental health servicesappropriate for childrenand young peoplewho offend?Children in the youth justice system arethree times more likely than others to showthe early signs of mental ill health. Manyhave complex needs, which on their own donot meet the criteria for community supportservices but which together undermine theirability to achieve their potential. PCTs havethe opportunity to intervene early to reducethe chances of costly poor mental health asthese young people mature.Action:PCTs should commissionsystematic processes toidentify young people with mental healthdifficulties at the first point of entry into theYouth Justice System. Youth Justice Diversionand Liaison workers should be funded toscreen young people before charge and toliaise with the police, courts and the YouthOffending Teams to refer them to appropriatesupport services.Local work should be supported throughregionally commissioned specialist teamsfor young people and families with the mostcomplex needs. These teams would advise onand work with those small number of caseswith the highest level of vulnerability andposing the greatest level of complexity andrisk in the region.Integrated service teams:In January 2007, Telford and Wrekinintroduced ‘integrated service teams’ toimprove access to early interventions,coordinate partnership working and makeexpertise more readily available to frontlinepractitioners. The teams have been ableto reduce inappropriate referrals to morespecialist and often more costly services suchas CAMHS due to their knowledge of local carepathways and their increased confidence insupporting cases at this less specialist level.

2Does the <strong>PCT</strong> commission‘places of safety’?Where a person is suspected of having amental health problem and is in need ofimmediate care or control, the police can useSection 136 of the <strong>Mental</strong> <strong>Health</strong> Act 1983to take the person from a ‘public place’ to a‘place of safety’ <strong>for</strong> up to 72 hours.Police stations are often crowded and chaoticplaces. The <strong>Mental</strong> <strong>Health</strong> Act Code of Practicesays that they should only be used as a lastresort. Yet an estimated 11,000 people aredetained in police stations as places of safetyeach year and many police <strong>for</strong>ces say theyhave no alternative.Action:Appropriately staffed Placeof Safety suites shouldbe commissioned by <strong>PCT</strong>s, preferably inhospitals, <strong>for</strong> individuals detained undersection 136. The use of the third sector asservice providers can be particularly useful.3Has the <strong>PCT</strong> commissionedservices to enable courtsto arrange <strong>Mental</strong> <strong>Health</strong>Treatment Requirements(MHTRs)?The MHTR is an option available to sentencersthat ensures mental health treatmentalongside other community sentence options.It can be particularly effective <strong>for</strong> people whohave disengaged from services. But it hasbeen used very little. Local mental healthteams are not always equipped or willing totake on clients with an offending history.Action:<strong>PCT</strong>s should ensure thatthe services theycommission are available and responsive tothe needs of people needing services in thecourts, and that the protocols <strong>for</strong> deliveringMHTRs are in place.4Has the <strong>PCT</strong> commissioned‘equivalent’ mental healthservices <strong>for</strong> its prisons?About 90% of adult prisoners have at leastone mental health problem, while one in <strong>10</strong>has a severe mental illness: ten times the rateoutside prison. <strong>Mental</strong> health ‘inreach’ teamsare still overstretched and under-resourced,and prison mental health care falls wellshort of what is equivalently available in thecommunity.Last year, £20.8 million was spent on mentalhealth care in prisons. This is just £300 perprisoner and is only about a third of what isneeded. Spending on prison mental healthcare also varies widely across the country.Some NHS regions spend more than twice asmuch per prisoner than others. This variationis not explained by different levels of need orcosts.Action:<strong>PCT</strong>s should ensure theycommission an equivalentlevel of mental health care <strong>for</strong> prisonerscompared to that available in the community.5Are local offendermental health servicesappropriate <strong>for</strong> women?Female offenders experience very high levelsof mental distress, often related to separationfrom their children. One third of womenin prison have had a previous psychiatricadmission. Half of all self-harm incidents inprison are by women despite only making up6% of the prison population.Action:<strong>PCT</strong>s should commissiongender-sensitive andspecific services <strong>for</strong> women, as recommendedby the Corston Report in 2007.