Land is Life - Forest Peoples Programme

Land is Life - Forest Peoples Programme

Land is Life - Forest Peoples Programme

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

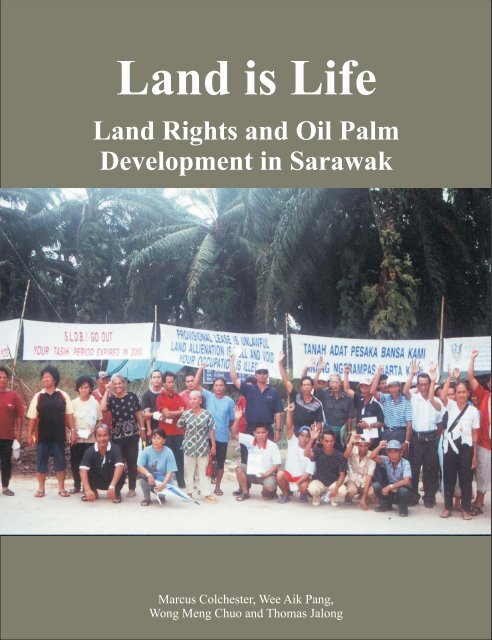

<strong>Land</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>Life</strong><strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil PalmDevelopment in SarawakMarcus Colchester, Wee Aik Pang,Wong Meng Chuo and Thomas Jalong

<strong>Land</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>Life</strong>: <strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawak by Marcus Colchester, WeeAik Pang, Wong Meng Chuo and Thomas Jalong was first publ<strong>is</strong>hed in 2007 by <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong><strong>Programme</strong> and Perkumpulan Sawit Watch.Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> the fourth in a series of publications by <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> and Sawit Watchexamining the social and environmental impacts of oil palm development. Two previousstudies were publ<strong>is</strong>hed in 2006, Prom<strong>is</strong>ed <strong>Land</strong>: Palm Oil and <strong>Land</strong> Acqu<strong>is</strong>ition in IndonesiaImplications for Local Communities and Indigenous <strong>Peoples</strong> by Marcus Colchester, NormanJiwan, Andiko, Martua Sirait, Asep Yunan Firdaus, A. Surambo and Herbert Pane publ<strong>is</strong>hed by<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong>, Sawit Watch, HuMA and ICRAF and Ghosts on our own land: oilpalm smallholders in Indonesia and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil by MarcusColchester and Norman Jiwan publ<strong>is</strong>hed by <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> and Sawit Watch. Athird book by Dr. Afrizal, The Nagari Community, Business and the State was publ<strong>is</strong>hed by<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong>, Sawit Watch and Universitas Andalas in 2007.Perkumpulan Sawit WatchJl. Sempur Kaler No. 2816129 Bogor, West JavaIndonesiaTel: +62-251-352171Fax: +62-251-352047Email: info@sawitwatch.or.idWeb: www.sawitwatch.or.id<strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong>1c Fosseway Business CentreStratford Road, Moreton-in-MarshGL56 9NQ, EnglandTel: 01608 652893Fax: + 44 1608 652878Email: info@forestpeoples.orgWeb: www.forestpeoples.orgCopyright@ FPP and SW ©All rights reserved. Sections of th<strong>is</strong> book may be reproduced in magazines and newspapersprovided that acknowledgement <strong>is</strong> made to the authors and to <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> andPerkumpulan Sawit Watch.Th<strong>is</strong> publication <strong>is</strong> also available in Bahasa MalaysiaISBN: 978-979-15188-3-3Cover photo: Community of Sungai Bawan protest against SLDB.Credit: Wong Meng Chuo

<strong>Land</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>Life</strong><strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil PalmDevelopment in SarawakMarcus Colchester, Wee Aik Pang,Wong Meng Chuo and Thomas Jalong

Our community has lived in th<strong>is</strong> area for manydecades and we had cultivated the land with padi,fruit trees and some cash crops including oil palm ona small scale. But now, we are told that we have norights and we were even ordered to stop using andcultivating our lands. If the government has acquiredour lands and given it to the company, why are wenot informed or notified and compensatedaccordingly? Our lands and properties are takenbehind our back and <strong>is</strong>sued to others. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> sheerrobbery. The government and our leaders should beprotecting our rights to our lands and not simplygiving it to others without informing and consultingus. Some people are allowed to thrive but some areleft to be deprived. We have engaged a lawyer todefend us and to apply for the order to be set aside.Tua Rumah, Jupiter Anak Segaran, Iban Village Chief,Rumah Jupiter, Sungai Gelasa, Lembong, Suai, Sarawak

Contents:1. Executive Summary 12. <strong>Land</strong>, People and Power in Sarawak 43. <strong>Land</strong> Tenure and the Law 94. The Palm Oil Sector in Malaysia 215. Sarawak Government Policies on Plantations 266. Oil Palm Plantations in the Courts 357. Community Experiences with Oil Palm Plantations 428. Sarawak and the RSPO 759. Ways Forward 87References 90Annex 1: The RSPO Principles and Criteria 93Annex 2: Methods used in th<strong>is</strong> study 97

Acknowledgements:Th<strong>is</strong> study was coordinated by the <strong>Forest</strong> <strong>Peoples</strong> <strong>Programme</strong>, in partnership withSawit Watch and colleagues in Sarawak, and was carried out with funding fromOxfam (GB) and Global Green Grants. We are grateful to the local communitymembers who participated in the survey and who used the opportunity to voice theirconcerns about their situation. We have sought to present their views as accurately aspossible. We would also like to thank Harr<strong>is</strong>on Ngau, Baru Bian, See Chee How,Dominique and Paul Rajah, and Nicholas Mujah for help with data collection. We arealso grateful to Rebecca Whitby, Lou<strong>is</strong>e Henson and Julia Overton for help withproof-reading. However, it <strong>is</strong> the authors alone who take responsibility for thestatements and interpretations presented in th<strong>is</strong> report.

I am very concerned about th<strong>is</strong> development because itaffects my people’s livelihood. I do not agree with th<strong>is</strong>type of development and the manner it <strong>is</strong> conducted.The development of plantations in th<strong>is</strong> area willdefinitely result in the destruction and loss of theresources on our lands which we depend on for oursurvival. The company should recogn<strong>is</strong>e our ex<strong>is</strong>tencehere. Our people were born here, brought up andnurtured in th<strong>is</strong> area and we want to continue to live onth<strong>is</strong> land and surrounding forests.Alung Ju, Penan Village Chief of Long Singu,Peliran, Belaga D<strong>is</strong>trict, Kapit Div<strong>is</strong>ion, Sarawak

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawak1. Executive SummarySarawak <strong>is</strong> the largest State of the Federation on Malaysia and <strong>is</strong> located on the<strong>is</strong>land of Borneo. It <strong>is</strong> experiencing a rapid expansion of oil palm plantationswhich have led to growing conflicts with the indigenous peoples. TheMalaysian Constitution gives jur<strong>is</strong>diction over land to constituent States and inSarawak th<strong>is</strong> has led to the emergence of a political elite, whose power rests onthe exploitation of natural resources and which has dominated the politicaleconomy for the past 30 years.Although the rugged and forested interior of Sarawak <strong>is</strong> mainly populated byindigenous peoples, referred to locally as ‘natives’ and Dayaks, who compr<strong>is</strong>ethe largest ethnic grouping in the country, these peoples have relatively littleaccess to political power. Under customary law, the majority of the interior ofBorneo <strong>is</strong> owned and controlled by community groups and complex customarylaws regulate who and how lands are owned, regulated and transferred.Malaysia has a plural legal regime, meaning that it accepts the simultaneousoperation of d<strong>is</strong>tinct bodies of law, and custom <strong>is</strong> upheld under the FederalConstitution. Native authorities and courts are officially recogn<strong>is</strong>ed in Sarawakand continue to admin<strong>is</strong>ter community affairs and deliver local justice, meaningthat custom <strong>is</strong> a living and active source of rights in Sarawak, both in law and inpractice.However, since the colonial period and progressively thereafter, through a seriesof laws and regulations, the Government of Sarawak has sought to limit theexerc<strong>is</strong>e of ‘Native Customary Rights’ in land, freezing their extension withoutpermit and interpreting them as weakly secure use rights on State lands.Moreover, although the Government admits that some 1.5 to 2.8 millionhectares of land are subject to ‘Native Customary Rights’, it has not revealedwhere such lands are, meaning that most communities are unsure whether orwhat part of their lands are recogn<strong>is</strong>ed under the Government’s limitedinterpretation of their rights.1

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakSince natural resource-based development <strong>is</strong> a central plank of theGovernment’s economic policy, d<strong>is</strong>putes over land are common. In a series ofcases in the higher courts in Sarawak and Malaysia, judges have upheld nativepeoples’ land claims as cons<strong>is</strong>tent with the Malaysian Constitution and commonlaw. These cases imply that the Government of Sarawak’s restrictiveinterpretation of ‘Native Customary Rights’ <strong>is</strong> incorrect. Cons<strong>is</strong>tent withinternational human rights law, the courts have accepted that indigenouspeoples’ have rights in their lands on the bas<strong>is</strong> of their customs and not as aresult of grants by the State.The palm oil sector in Malaysia <strong>is</strong> in a phase of rapid expansion, with exportsexpected to exceed M$ 35 billion in 2007, now given further impetus by globaldemand for ‘bio-fuels’. With land on the Peninsula now in short supply, muchof the planned expansion of the sector will take place in Sarawak. Sarawak hasbeen experimenting with oil palm plantations for 30 years but early State-runschemes were less successful. The Government <strong>is</strong> now encouraging privatesector expansion including on ‘Native Customary <strong>Land</strong>s’ and plans to almostdouble the area under oil palms to 1 million hectares within the next three years,including planting on customary lands at a rate of 60,000 – 100,000 hectares peryear.Under the so-called Konsep Baru, the ‘New Concept’, native land owners areexpected to surrender their lands to the State for 60 years to be developed asjoint ventures with private companies, in which the State acts as Trustee onbehalf of the customary owners. There <strong>is</strong> a lack of clarity about exactly hownative landowners get benefits during these schemes and how they can reclaimtheir lands on the expiry of the lease.Owing to conflicting interpretations of the extent of ‘Native Customary Rights’and d<strong>is</strong>putes about compensation, due process and prom<strong>is</strong>ed benefits, there arenow over 100 cases in the courts of Sarawak filed on behalf of indigenousplaintiffs relating to d<strong>is</strong>putes over land, of which the study identified some 40cases related to palm oil.2

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakDetailed testimonies collected from 12 indigenous communities affected by oilpalm revealed the following major problems:• Conflicts and d<strong>is</strong>putes over land• Lack of respect for customary rights• Absence of transparent communications and consultations• Violation of the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent• Denial of people’s right to represent themselves through their own chosenrepresentatives• Limited or absent payments of compensation• Lack of transparency and participation in Environmental ImpactAssessments• Inadequate mechan<strong>is</strong>ms for the redress of grievances.State promotion of the oil palm sector in Sarawak <strong>is</strong> at odds with the principlesand criteria of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a number ofmembers of which have been identified to be operating in Sarawak.Without legal and procedural reforms in Sarawak, wide-scale compliance withthe RSPO standard seems unlikely. The current system harms communityinterests and may also d<strong>is</strong>courage investment in such a r<strong>is</strong>ky and conflictualsector. The report recommends legal and procedural reforms, by both theGovernment and companies, to bring them into line with international law andindustry best practice.3

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawak2. <strong>Land</strong>, People and Power in SarawakThe Federation of Malaysia <strong>is</strong> compr<strong>is</strong>ed of thirteen states and three federalterritories that are geographically spread over Peninsula Malaysia and thenorthern parts of the <strong>is</strong>land of Borneo. Under the federal constitution, theseparation of jur<strong>is</strong>dictions and powers are clarified. While <strong>is</strong>sues such asnational security, foreign policy and trade are matters for the FederalGovernment, the policies and laws concerning lands and forests are under thejur<strong>is</strong>diction of the individual States. To accommodate local sensitivities, whenSabah and Sarawak were invited to join the Malaysian Federation in 1963, thetwo eastern states of Sabah and Sarawak were also given jur<strong>is</strong>diction over theirWest Malaysian counterparts, for example in immigration, by which the twoEast Malaysian state governments technically still have full control over entryinto the two states by West Malaysians.However, through the Malaysian political system which has been character<strong>is</strong>edin practice by the dominance by one single coalition of ethnic-based partiessince independence, and by means of the centralization of political powers inthe hands of the Prime Min<strong>is</strong>ter, the federal government continues to exerc<strong>is</strong>edirect and indirect control over the states. The mere fact that the PrimeMin<strong>is</strong>ter’s consent <strong>is</strong> absolute over the appointment of state chief min<strong>is</strong>ters inWest Malaysia and increasingly in Sabah demonstrates the political influence ofthe federal over state governments. In addition, through annual budgetary andpolicy dictates, the federal government effectively exerts considerable controlover matters which are in the realm of state governments.4

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakMap of Malaysia 1The whole of the Peninsula and the <strong>is</strong>land of Borneo were once home toindigenous peoples, with unique languages, traditions, customs, culture andidentities. Adat, or traditional governance systems, ex<strong>is</strong>ted long before anyforeigners set foot on their lands and they enshrine and ensure the rights ofpeople over their lands and their usage of lands.The advent of colonial rule and the subsequent creation of a new nation withstatutory laws have long over-shadowed the traditional laws. When state-drivendevelopment was far and few, concentrated mostly in expanding urban centres,the conflicting laws were not very consequential. But when logging fastexpanded into the indigenous peoples’ territories, the might of the governmentproclaimed its dominance. Since then, expanding settlements, infrastructuraladvance, dams, agricultural schemes and so on have added to the encroachmentonto indigenous communal lands. With primary rainforests making way forsecondary forests and then mono-crop plantations of fast-growing trees, rubber1 Sourced from Sarawak Government Website at http://www.sarawak.gov.my/content/view/5/10/5

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakand oil-palm, the conflict between the two bodies of law has become moreevident, more v<strong>is</strong>ible and more blatant.Physically, Sarawak <strong>is</strong> the largest state in the Federation of Malaysia. Its landarea of some 124,449.51 square kilometres <strong>is</strong> about the size of the whole ofPeninsula Malaysia with a land mass of 131,573 square kilometres. Sarawak <strong>is</strong>divided into eleven div<strong>is</strong>ions, with Kuching as the capital of Sarawak. The otherdiv<strong>is</strong>ions are Sri Aman, Sibu, Miri, Limbang, Sarikei, Kapit, Kota Samarahan,Bintulu, Mukah and Betong. Kuching <strong>is</strong> the seat of government for Sarawak.Sarawak <strong>is</strong> not famous for the richness of its soils and the suitability of its landfor agriculture. Nearly 70% of the State <strong>is</strong> classified as ‘hilly’ and only 3.5million hectares of the State <strong>is</strong> considered somewhat suitable for agriculture.Nevertheless, especially since the early 1990s, Sarawak has experienced a rapidand still continuing expansion of oil palm estates, which are the subject of th<strong>is</strong>study. 2Table 1: Ethnic Composition of SarawakEthnic Groups% popn.Malay 23.0Iban 30.1Bidayuh 8.3Melanau 5.6Other natives (‘Orang Ulu’ – upriver peoples) 5.9Chinese 26.7Others 0.4Source: Jomo et al 2004:8As at 2005, Sarawak had a population of 2.31 million people. 3 Sarawak boasts arich h<strong>is</strong>tory of diverse peoples from when indigenous communities were spreadall over the <strong>is</strong>land of Borneo. Long before the ex<strong>is</strong>tence of the Brit<strong>is</strong>h and Dutchcolonial powers, which divided up the <strong>is</strong>land, indigenous communities had2 Jomo et al. 2004:149-150.3 Yearbook of Stat<strong>is</strong>tics, 2005, Department of Stat<strong>is</strong>tics, Malaysia6

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakex<strong>is</strong>ted for generations, each with their respective customs, traditions, culture,languages and identities.Officially, Sarawak now compr<strong>is</strong>es some 40 ethnic groupings. The indigenousDayak, a collective term used to group all indigenous communities, also knownwithout any pejorative sense as ‘natives’ in Sarawak, still dominate the ruralsettings, even though increasing numbers spend more time in urban areas thanin their rural homes.Ethnic Composition composition of of Sarawak (%) (% )MalayIbanBidayuhMelanauOther NativesChineseOthersSource: Based on Jomo et al. 2004:8Although Sarawak has never experienced the kind of racial riots that broke outin the Peninsular in 1969, competition for power in Sarawak, as in thePeninsula, has for the most part cleaved along racial lines and has been heavilyinfluenced by the politics of the Federal Parliament. 4 Early attempts by Dayakto assert an independent line from the dominant authorities in the Peninsulawere not tolerated and the first and only Dayak Chief Min<strong>is</strong>ter of Sarawak,4 Leigh 1974; Searle 1983; Wong 1983; Colchester 1992.7

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakStephen Kalong Ningkan, was removed from office through the application ofretrospective constitutional amendments in 1966.Since that time, a Muslim-Melanau elite has dominated power in Sarawak basedon a patrimonial system for d<strong>is</strong>pensing benefits, notably in land, forestryconcessions, development contracts and infrastructure schemes, which hascons<strong>is</strong>tently found ways of winning over even politicians opposing the rulingcoalition. The power of th<strong>is</strong> elite has never been overtly challenged by theFederal authorities so long as they have remained steadfastly loyal to theNational Front Coalition which, led by the United Malays NationalOrgan<strong>is</strong>ation, has dominated the Federal Parliament since independence. Thepresent Chief Min<strong>is</strong>ter of Sarawak, Taib Mahmud, has now been in powerwithout interruption, though not without challenge, 5 for more than 25 years.The net result <strong>is</strong> that the Dayaks, who are the single most numerous socialgrouping and who predominate in rural areas, are relatively powerless in termsof national politics and dec<strong>is</strong>ion-making about land. Such Dayak politicalparties as do ex<strong>is</strong>t have been co-opted into the national front coalition and nolonger independently defend the rights of Dayak communities to their lands.5 Yu 1987.8

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawak3. <strong>Land</strong> Tenure and the LawThe Dayak peoples of Sarawak, who compr<strong>is</strong>e the most numerous section ofSarawak society and make up the majority of the peoples in the interior, havevery long traditions of land occupation. They regulate their affairs according to‘custom’ (adat), a body of beliefs, social norms, customary laws and traditionalpractices which <strong>is</strong> passed on from one generation to the next as oral tradition.Flexible and adaptive to change, adat also provides the charter underpinningDayak notions of land ownership and control, regulating how land <strong>is</strong> shared outamong community members, how it <strong>is</strong> inherited, how rights are created andforfeited and to whom and how rights can be transferred.Although the details of land ownership vary greatly among the different Dayakpeoples, a common pattern can be d<strong>is</strong>cerned. Each community <strong>is</strong> conceived asowning a territory, menoa in the Iban language. These village territories, havewell-known boundaries, often agreed between neighbouring villages inmeetings, that commonly run along rivers, up creeks to their headwaters andalong watersheds and so back down and round to their starting point. Thevillage territory <strong>is</strong> a communally owned area – it belongs to the community as awhole not to any one person – and includes the forests, rivers, creeks, streamsand farmlands and other resources within it. The land <strong>is</strong> not just a geographicalarea; it <strong>is</strong> also a lived experience, and tales and legends, village h<strong>is</strong>tories andimportant events, link the land to the people in a profound way that gives peoplea sense of belonging to the land, just as the land belongs to them. Whereboundaries between villages have been d<strong>is</strong>puted or have needed clearerdemarcation, they may be marked with cairns or blazed on trees, but for themost part the bounds are known and und<strong>is</strong>puted, being accepted by all around.Within these communal territories, individuals and families acquire personalrights, subject to village consensus, by clearing forests, or opening up land, forfarmlands. These areas then become individual or family owned areas whereeach family ra<strong>is</strong>es their crops and makes a living. Some farmlands on fertilesoils, typically in the lower ground, are more-or-less permanent but most of the9

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakupland farms require rotations if productivity <strong>is</strong> to be sustained. Rights in landare retained by individuals during forest fallows, when the farmlands are left toregenerate forest cover and recuperate their nutrient levels, before being clearedagain for another round of farming. <strong>Forest</strong> fallows, temuda in Iban, are a vitalpart of the agricultural economy – a rational system for making a living off thepoor soils that are common in the interior of Borneo. Quite complicated rulesmay also define who has first rights to extend their farmed areas and in whichdirection. Typically, an owner has first rights to extend their farm uphill awayfrom the river, but not upstream along the river bank, so that access to rivertransport <strong>is</strong> shared and not monopol<strong>is</strong>ed by one or a few villagers. Some farmsmay be far from villages and crops will be looked after and protected from pestsby people going to live in their d<strong>is</strong>tant farms for long periods. Small semipermanenthouses, dampa in Iban, are erected in these further flung farms tomake these extended periods of work away from the longhouse comfortable.All family or individually owned lands are heritable, with heirs being clearlydefined by customary laws – norms of inheritance vary greatly among thedifferent peoples. Rights in these lands are maintained so long as the persons orfamilies continue to work the land or reside in the communities or remainnearby. To retain their rights in land, customary laws may require members tomaintain their links with the community, for example by residing in thelonghouse a minimum number of nights per year. Once they are considered tohave abandoned their lands, these lands then revert to communal ownership andmay be shared out to new families or other community members. The principlein play here <strong>is</strong> important. The underlying right to land <strong>is</strong> vested in thecommunity, and individual or family rights over land earned by the inheritance,clearance, occupation and use are nested within that underlying right of thecommunity. Customary rules thus regulate the way private or family lands maybe transferred between owners. Again details vary greatly, but commonly it <strong>is</strong>not considered acceptable for lands to be sold to outsiders, although leases andtemporary transfers may be permitted. 6These customary rights systems can be seen to have changed somewhat in thepast sixty years. As populations have grown and relations with the market have6 Richards 1961; Sandin 1980; Hong 1987; Colchester 1992.10

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakdeepened, village boundaries have been subdivided as new longhouses havesplit off from parent communities. In other cases, territories which used toembrace several longhouses are now more clearly defined around eachsettlement. With greater involvement in the cash economy, family andindividual farms have expanded to include rubber plantations, cacao farms,pepper gardens and other crops grown for the market and not for immediate use.In some places, menoa lands without any personal ownership rights overlayingthem may have virtually d<strong>is</strong>appeared, as almost the whole of a community’sterritory has been parcelled up into personal rights areas. <strong>Land</strong> markets havebegun to operate in some areas. While some see these transformations asevidence of the collapse of tradition, they are better seen as evidence of thevitality and adaptability of adat.Custom, <strong>Land</strong> and Admin<strong>is</strong>trationMalaysia as a whole has a plural legal system – which <strong>is</strong> to say that severalbodies of law are recogn<strong>is</strong>ed as having validity in the country. Custom <strong>is</strong>recogn<strong>is</strong>ed and upheld in the Constitution of the Malaysian Federation. Thecustomary authorities of village headmen (tua rumah), regional chiefs(penghulu) and paramount chiefs (pemancha), are also recogn<strong>is</strong>ed by theSarawak Government and receive a small stipend for their services inmaintaining the rule of law, both admin<strong>is</strong>trative and adat. As in Sabah, so inSarawak a large proportion of daily affairs are left to adat and d<strong>is</strong>putes areresolved in officially recogn<strong>is</strong>ed ‘native courts’, which continue to adjudicateover village affairs including d<strong>is</strong>putes over land within and between villagesand even, on occasion, with outside parties. 7 Custom <strong>is</strong>, thus, a living and activesource of rights in Sarawak, not just in practice but also in law.However, when it comes to the admin<strong>is</strong>tration of land, since the colonial periodSarawak can be seen to have pursued a somewhat divergent approach. On theone hand, the State has respected custom, has upheld customary rights systemsand has sought to protect native lands from exploitation by outsiders. On theother hand, the State has sought to limit customary rights in a number of ways.7 Phelan 2003.11

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakIn the first place the State has sought to d<strong>is</strong>courage shifting cultivation, whichwas seen as wasteful and environmentally imprudent and prejudicial toeconomic development. In the second place the State has sought to encourageDayaks to settle into larger villages, develop permanent crops and engage in themarket and give up their ‘nomadic’ way of life. In the third place, the State hasdeclared large areas of ‘vacant’ or ‘idle’ lands, which may in fact be subject tocustomary rights, to be ‘Statelands’ (public lands without private or communalowners). In the fourth place, large areas especially of upland forests, have beendeclared <strong>Forest</strong> Reserves and Protected Areas and procedures have beenunilaterally imposed and declared which have sought to limit or extingu<strong>is</strong>hcustomary rights in these areas. Finally, as th<strong>is</strong> report explores in more detail,the State has sought to take over extensive areas for plantations, by a variety ofdifferent means. All these strategies to limit the native peoples’ land rights haveled to protests and generated conflict. 8To protect and order land matters, and to encourage a transition to a more‘modern’ system of land use, the colonial State introduced a system forclassifying lands into various categories. 9 Mainly along the coast, ‘Mixed Zone<strong>Land</strong>s’, were designated in which land markets could freely operate, lands wereheld by private title and reg<strong>is</strong>ters of land ownership were developed using theTorrens System of individual land ownership and cadastral surveys. Such landscould be held by any legal person in Sarawak, whether native or not. ‘NativeArea <strong>Land</strong>s’, also mainly near the coast, were areas of native occupation whereindividual land titling was promoted but where land markets were restrained –non natives could not own land in such areas – in order to protect the nativesfrom being taken advantage of by unscrupulous or more market-savvy buyers.‘Native Communal Reserves’ were to be areas, which could be declared by theGovernment, regulated by customary law. ‘Native Customary <strong>Land</strong>s’ wereareas where customary systems of land ownership prevail according to adat butsubject to restrictive interpretations of ‘Native Customary Rights’, as explainedbelow. A fifth catch-all category, ‘Interior Area <strong>Land</strong>s’ was designated overareas where rights and uses were yet to be clearly defined, while the finalcategory, ‘Reserved <strong>Land</strong>s’, included all lands gazetted for special use such as8 For a longer d<strong>is</strong>cussion see Hong 1987; Colchester 1992.9 <strong>Land</strong> (Classification) Ordinance 1948.12

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakforestry reserves, protected areas and so on. Th<strong>is</strong> system of land classificationwas retained in the post- colonial era and prevails today.Most of the cases d<strong>is</strong>cussed in Chapters 5 and 6, below, concern areas which ared<strong>is</strong>puted as falling into these various categories. While the natives may considertheir areas to be ‘Native Customary <strong>Land</strong>s’, the government may hold them tobe ‘Interior Area <strong>Land</strong>s’ which are by default assumed to be Statelands. Or,where the government may accept that these areas fall in the category of ‘NativeCustomary <strong>Land</strong>s’, it may be seeking to develop these lands as plantationsthrough various forms of ‘<strong>Land</strong> Consolidation and Rehabilitation’ which mayaim to convert the lands, in the longer term, from being ‘Native Customary<strong>Land</strong>s’ into ‘Native Area <strong>Land</strong>s’ under private title.Customary Rights and the <strong>Land</strong> CodeDuring the century of the Brooke Raj (1840-1946), introduced laws were notvery clear about land rights. While the Rajah made various declarations abouth<strong>is</strong> rights over the whole territory, which was progressively expanded from asmall area around Kuching to encompass the present extent of the State, therulers also declared their intent to protect the native peoples’ rights. For themost part, D<strong>is</strong>trict Officers allowed native authorities and native courts toresolve land d<strong>is</strong>putes and only got involved when called in to help sort out moreintractable problems. In adjudicating in the native courts, D<strong>is</strong>trict Officersapplied their understanding of adat, and they gradually built up records of theboundaries of the various communities under their jur<strong>is</strong>diction, which werebound together in a volume kept in the d<strong>is</strong>trict office and referred to as ‘theBoundary Book’. Instructions from the Central Secretariat were sent out toofficials on how they should determine the boundaries of all villages and thesewere to include not only farmed areas but also areas of natural forest necessaryfor expansion and wider livelihood needs. 10 Though some of the BoundaryBooks were lost during the Second World War, they remained in use up untilthe 1950s and in the Baram area, at least, continued to be added to and referred10 Eg Brooke Raj Secretariat Circular No 12/1939 cited at length in Colchester 1992:70-71.13

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakto in the settlement of d<strong>is</strong>putes into the 1970s. They have also been called inevidence in recent cases in the courts.Sarawak was ceded to the Brit<strong>is</strong>h after the Second World War, and theInstrument of Cession included an important ‘savings clause’ which transferredthe rights of the Rajah, the Rajah’s Council and the State and Government ofSarawak to the Brit<strong>is</strong>h Crown ‘but subject to ex<strong>is</strong>ting private rights and nativecustomary rights’. 11 However, under the Brit<strong>is</strong>h colonial admin<strong>is</strong>tration (1946-1963) a series of laws was then introduced which sought to place a morerestrictive interpretation on customary rights. 12 These laws were consolidated inthe 1958 <strong>Land</strong> Code, which remains, subject to various rev<strong>is</strong>ions, the main lawordering land matters in the State.The <strong>Land</strong> Code provides a little more detail of how ‘Native CustomaryReserves’, governed by customary law, should be establ<strong>is</strong>hed. These were to beconsidered to have been created on State land but have hardly beenimplemented. The <strong>Land</strong> Code also recogn<strong>is</strong>es ‘Native Customary Rights’(NCR). According to Section 5(2) of the <strong>Land</strong> Code, NCR can be establ<strong>is</strong>hedby:• The felling of virgin jungle and the occupation of the land therebycleared• The planting of land with fruits• The occupation of cultivated land• The use of land for a burial ground or shrine• The use of land for rights of way; and• Any other lawful method.The legal assumptions underpinning the colonial laws on land are questionable.In the first place the laws neglect to mention, or deliberately ignore, the widerareas of territory, beyond farmlands etc, held under customary law, which wererecogn<strong>is</strong>ed in the ‘Boundary Books’ and in the adjudications of the NativeCourts. Moreover, the 1958 <strong>Land</strong> Code and the previous 1948 <strong>Land</strong>11 Cited in Bulan 2006:47.12 Porter 1968.14

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakClassification Ordinance, assumed that the colonial State has a proprietary rightin the land and, while allowing for the establ<strong>is</strong>hment of ‘Native CustomaryRights’ on Interior Area <strong>Land</strong>, treated these as licensed use rights on Statelands.Amendments have since been passed by the now independent State of Sarawakwhich seek to further limit these rights. A 1994 amendment empowers themin<strong>is</strong>ter in charge of land matters to extingu<strong>is</strong>h native customary rights toland. 13 In 1996, the burden of proof with respect to NCRs was placed on thenative claimant against the presumption that the land belongs to the State. Thenin 2000, the <strong>Land</strong> Code (Amendment) Ordinance removed the phrase ‘any otherlawful method’ from Article 5. 14 Other laws were also passed to limit nativeland claims. In 1987, it was made illegal for communities to block companiesfrom having access to their logging and plantation enterpr<strong>is</strong>es even if theseroads crossed areas claimed by natives as customary lands. Ten years later, inresponse to a successful court case upholding a community’s claim to NativeCustomary Rights, a law was also passed d<strong>is</strong>qualifying communities frommaking their own maps of their customary lands for use in the courts.The intent of the colonial and independent State of Sarawak to progressivelylimit and restrict NCRs <strong>is</strong> plain. The most contentious aspect of the laws,however, was a prov<strong>is</strong>ion in the 1958 <strong>Land</strong> Code that froze all extension ofnative customary rights without permit after the 1 st January 1958. 15 Later, theGovernment <strong>is</strong>sued instructions to d<strong>is</strong>trict officials to cease giving out suchpermits. From the Government’s point of view, therefore, native communitiesdo not enjoy NCRs if their farms were not establ<strong>is</strong>hed by 1958, unless they canshow they have one of the rare permits that was <strong>is</strong>sued since that date.In sum, the laws relating to lands and NCRs have been progressively tightenedby limiting the definition of NCRs and the procedures for establ<strong>is</strong>hing them; by13 The fact that th<strong>is</strong> prov<strong>is</strong>ion was written into law argues that the State did recogn<strong>is</strong>e that, at leastup until th<strong>is</strong> time, native customary rights may indeed not have been extingu<strong>is</strong>hed (and see later).14 The courts have however already ruled that th<strong>is</strong> legal sleight of hand cannot be appliedretrospectively15 In fact the same restriction had been imposed from 1 st January 1955 by the <strong>Land</strong>(Classification) (Amendment) Ordinance 1955.15

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakfacilitating their extingu<strong>is</strong>hment; by giving the State sole power to decide onrates of compensation; by restricting the free movement of native peoples; andby increasing the penalties for failures to comply with State leg<strong>is</strong>lation. 16In different official documents and statements, the Government has variouslyadmitted that between 1.5 million hectares and 2.8 million hectares of theterritory of Sarawak <strong>is</strong> subject to Native Customary Rights. However, thelocation and extent of the areas that the government already accepts as beingencumbered with NCRs has not been made public. Consequently mostcommunities are unsure if the areas that they consider to be theirs by custom arerecogn<strong>is</strong>ed by the Government as areas of ‘Native Customary Rights’. In theface of th<strong>is</strong> confusion, many native people thus refer to their customary lands as‘Native Customary Rights’ or ‘Native Customary Rights <strong>Land</strong>s’, although theseterms, as framed by Sarawak <strong>Land</strong> Code, have much more limited meanings.<strong>Land</strong> Rights in the CourtsThe very wide gap between customary rights as conceived by the native peoplesand the ‘Native Customary Rights’ as interpreted by the Government withreference to the <strong>Land</strong> Code, has led to numerous land d<strong>is</strong>putes many of whichhave been referred to the courts. Chapters 5 and 6 look into some of these casesas they relate to oil palm. Some of the key considerations and findings of thecourts with respect to land in general are however summar<strong>is</strong>ed here.In their adjudication of these land d<strong>is</strong>putes in Sarawak and in the Federal Courtin Kuala Lumpur, judges have not only taken into account the <strong>Land</strong> Code andother pieces of law relating to land in Sarawak but also the Constitution ofMalaysia and other framing pieces of national and State law. As defined in theInterpretation Acts of 1957 and 1958, ‘Law’ in Malaysia ‘includes written law,the common law in so far it <strong>is</strong> in operation in the Federation or any part thereof,and any custom or usage having the force of law in the Federation or in any partthereof.’ Likew<strong>is</strong>e, following the cession of Sarawak to the Brit<strong>is</strong>h in 1946, theSarawak authorities passed the Application of Law Ordinance 1949, which16 IDEAL 1999.16

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakprovided for the reception of Engl<strong>is</strong>h common law into Sarawak, ‘subject tosuch qualification as local circumstances and native customs rendernecessary’. 17 Therefore, the courts in Sarawak as well as in Malaysia may takeinto account the findings of other courts that use Engl<strong>is</strong>h Common Law andadapt them to the realities and customary laws of Sarawak. They thus draw on awell-developed body of jur<strong>is</strong>prudence about native rights from countries as farafield as Nigeria, New Zealand, Australia, Canada and South Africa, as well asjudgements given in the Privy Council in England.The courts in Sarawak and Malaysia have thus delivered some importantjudgements based on these legal precedents, on their own understanding ofcustomary law, the assertions of native people themselves and the pleadings ofthe lawyers acting on behalf of the native people. In the fully tried NCR landcase in Sarawak, Nor Ak Nyawai & Ors v Borneo Pulp Plantation Sdn Bhd &Ors [2001] 2 CLJ 769, the trial Judge referred to Mabo v State of Queensland(1992) 66 ALJR 408 which was followed in a Malaysian case of Adong binKuwau & 51 Ors v The Government of Johore [1997] 1 MLJ 418. H<strong>is</strong> Lordshipsaid:Th<strong>is</strong> journey through h<strong>is</strong>tory <strong>is</strong> necessary because, and it <strong>is</strong> commonground - ar<strong>is</strong>ing from the dec<strong>is</strong>ion in Mabo v State of Queensland(1992) 66 ALJR 408 which was followed in Adong bin Kuwau & 51Ors v The Government of Johore [1997] 1 MLJ 418 and whichdec<strong>is</strong>ion was affirmed by the Court of Appeal ([1998] 2 MLJ 158) -the common law respects the pre-ex<strong>is</strong>ting rights under native law orcustom though such rights may be taken away by clear andunambiguous words in a leg<strong>is</strong>lation. I am of the view that <strong>is</strong> true alsoof the position in Sarawak.In Adong bin Kuwau & 51 Ors v The Government of Johore [1997], the learnedJudge, after referring to the many cases in other jur<strong>is</strong>dictions that upheld nativerights, concluded that ‘Aboriginal people’ have their rights over their ancestralland protected under common law. At page 430 of H<strong>is</strong> Lordship’s judgment hesaid:17 Cited in Bulan 2006:47.17

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakMy view <strong>is</strong> that, and I get support from the dec<strong>is</strong>ion of Calder's Caseand Mabo's Case, the aboriginal peoples' rights over the land includethe right to move freely about their land, without any form ofd<strong>is</strong>turbance or interference and also to live from the produce of theland itself, but not to the land itself in the modern sense that theaborigines can convey, lease out, rent out the land or any producetherein since they have been in continuous and unbrokenoccupation and/or enjoyment of the rights of the land from timeimmemorial. I believe th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> a common law right which thenatives have and which the Canadian and Australian Courts havedescribed as native titles and particularly the judgment of Judson J inthe Calder's Case at page 156 where H<strong>is</strong> Lordship said the rights andwhich rights include '... the right to live on their land as theirforefathers had lived and that right has not been lawfullyextingu<strong>is</strong>hed......’ I would agree with th<strong>is</strong> ratio and rule that inMalaysia the aborigines common law rights include, inter alia,the right to live on their land as their forefathers had lived andth<strong>is</strong> would mean that even the future generations of theaboriginal people would be entitled to th<strong>is</strong> right of theirforefathers.Likew<strong>is</strong>e in Kerajaan Negeri Selangor & Ors v Sagong Tasi & Ors [2005] 4CLJ 169, the learned President of the Malaysian Court of Appeal referred toAdong and H<strong>is</strong> Lordship said: ‘It <strong>is</strong> too late in the day for the Defendants tocontend that our common law does not recognize aboriginal customary title’.These findings are uncomfortable for the Government of Sarawak. The StateAttorney General, who acts as legal counsel on behalf of the State Governmentin the many cases where it <strong>is</strong> a defendant, continues to argue for the colonialState’s, and now independent government of Sarawak’s, much more limitedinterpretation of ‘Native Customary Rights’. He argues that written laws takeprecedence over the doctrines of common law and that the colonial power andnow independent state, by reserving lands for other purposes have effectively18

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakextingu<strong>is</strong>hed customary rights, except for those expressly recogn<strong>is</strong>ed underState laws. 18The courts, however, continue to rule otherw<strong>is</strong>e. The most recent judgement ofthe Malaysian Federal Court, in the case of Madeli Salleh v Superintendent of<strong>Land</strong>s & Surveys & Anor [2005] 3 CLJ 697, re-affirmed in October 2007 thatthe principle of common law applies in Sarawak, contrary to the arguments ofthe State Attorney General. Th<strong>is</strong> highest court in Malaysia affirmed that inSarawak a communities’ rights in land remain, even after the land has beenreserved or gazetted by government order for another purpose. Since, in th<strong>is</strong>case, the government had not expressly extingu<strong>is</strong>hed the prior owner’s rights,nor paid due compensation for such as agreed by both parties, NativeCustomary Rights in the land endured.Plantation Development and the LawThe implications of these and other judgements for land developers in Sarawakare manifold. On the one hand, it <strong>is</strong> clear that the native peoples’ customaryrights in land obtain independent of any act or grant of the State. They enjoyedthese rights prior to the ex<strong>is</strong>tence of the State of Sarawak and these rightsendure today. Second, that these rights remain until and unless expresslysurrendered or extingu<strong>is</strong>hed through an agreed legal process and payment ofcompensation. Third, that without such a process, investors and companiesseeking to develop lands, for example for plantations in Sarawak, cannotassume that the area they are planning to develop <strong>is</strong> not encumbered with nativecustomary rights. The mere <strong>is</strong>suance of a licence, lease or permit by the StateGovernment to develop a plantation does not in law provide security againstother claims on the land.18 The Sarawak Attorney General’s legal position has been made known to the Malaysian HumanRights Comm<strong>is</strong>sion (SUHAKAM) (Attorney General 2007). A copy can be viewed athttp://www.rengah.c2o.org/assets/pdf/de0157a.pdf . Th<strong>is</strong> position has been repudiated by anumber of Sarawakian NGOs in a position paper available athttp://www.rengah.c2o.org/assets/pdf/de0162a.pdf19

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakThese judgements also bring Sarawak into line with interpretations ofindigenous peoples’ rights under international law. As noted in Chapter 8, thesenorms of law are also accepted by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil,which promotes best practices based on international norms and standards.Unless plantation companies deal fairly with native peoples and respect theirrights, their operations and investments are at r<strong>is</strong>k.20

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawak4. The Palm Oil Sector in MalaysiaLarge scale plantation development commenced in Peninsular Malaysia(Malaya as it then was) at the end of the 19 th century. Already by 1925, nearlyone million hectares of land had been cleared of forest and planted withrubber. 19 Oil palm development came later, mostly after independence, whenlarge-scale plantation development became a central plank in the nationaldevelopment policies. Since then, large scale plantation development for oilpalm has almost closed the land frontier in the Peninsular.By 2006, the export earnings of Malaysian palm oil industry scored a record ofM $ 31.8 billion, 20 while the production of crude palm oil increased by 6.1% to15.9 million tonnes. The industry <strong>is</strong> targeting a harvest of 16.5 million tonnes in2007. The total oil palm planted area has expanded to about 4.2 million hectares(compared with 2 million hectares in 2000), of which over 2.3 million hectaresare found in Peninsular Malaysia and 1.24 million hectares in Sabah, whileSarawak has 600,000 hectares. 21Although Sabah and Sarawak have been slower to get going, the scarcity ofavailable lands for further estates in the Peninsula, means that these twoBornean States are now the focus for plantation expansion and investment. Thecombined growth of Sabah and Sarawak in plantations development in 2006was 4.5% compared to 1.6% in Peninsular Malaysia. The two Bornean Statesnow hold a total planted area of about 1.83 million ha, accounting for 44% ofthe country’s total oil palm plantation size.19 Jomo et al. 2004:26.20 2006 palm oil exports hit record M$ 31.8 bn, The New Straits Times – Business Times, 11 thJanuary 2007, accessed online athttp://www.btimes.com.my/Current_News/BT/Thursday/Frontpage/BT338868.txt/Article/21 Campaign to combat negative attitude towards palm oil, The Star Online, 25 th June 2007,accessed online athttp://www.thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2007/6/25/nation/20070625184355&sec=nation21

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakIn terms of production, the two states produced a total of 6.91 million tonnes ofcrude palm oil in 2006, making up 43% of Malaysia’s total production of 15.9million tonnes. 22 About 12.6% of the total 33.01 million hectares of land area ofMalaysia are planted with oil palm trees, while Sarawak aims to double itspresent planted area to a million hectares by 2010, of which at least 400,000hectares are to be taken from areas recogn<strong>is</strong>ed by the government as being thenative customary land. 23 Oil palm <strong>is</strong> planned to take up over 2/3 rd of the 6million hectares allocated for agricultural expansion between 2000 and 2010 asset by the Third National Agriculture Plan (NAP3).Further impetus to oil palmexpansion <strong>is</strong> being given by international and national policies to develop palmoil as a ‘biofuel’. The national biofuel policy officially sets targets for fivestrategic ‘thrusts’ for use of the fuel in transport, industry, technologies, exportsand for a so-called ‘cleaner environment’. By blending 5% processed palm oilwith all diesels in the country, a new domestic market for 500,000 tonnes ofpalm oil per year will be created. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> equivalent to 40%-50% of the currentnational stock of palm oil. 2422 Sabah, Sarawak positioned for growth, The Star Online, 3 rd July 2007, accessed online on 3 rdJuly at http://biz.thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2007/7/3/business/18178105&sec=business23 Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development Sarawak, available online athttp://www.mlds.sarawak.gov.my/background/b_1.htm24 Min<strong>is</strong>try of Plantation Industries and Commodities, 21 March 2006, in www.palmoil.com22

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakFigure 1: Malaysia’s Palm Oil Export Trend (2001 – 2007) 25The target set by EU for 5.75% bio-diesel in its fuel mix in 2010 and 10% by2010 26 and from other countries 27 <strong>is</strong> also expect to boost exports of Malaysianpalm oil, on top of its other larger traditional client countries.China remained the top buyer of Malaysia's palm oil products last year,purchasing 3.58 million tonnes in 2006. The Netherlands was second, with 1.67million tonnes. Pak<strong>is</strong>tan was the third biggest buyer, consuming 957,35225 Sourced from "Palm oil exports po<strong>is</strong>ed to surpass RM35b th<strong>is</strong> year", New Straits Times -Business Times Online, 27 July 2007, accessed on same publication day athttp://www.btimes.com.my/Current_News/BT/Friday/Nation/35b.xml/Article/26 Sweden: EU must lift biofuel import tariffs, The New Straits Times – Business Times, 16 th July2007, accessed online athttp://www.btimes.com.my/Current_News/BT/Monday/Nation/rup14a.xml/Article/27 Brazil government's mandate on the use of 2 per cent biodiesel (B2) content in diesel in 2008,as per "Brazil buying more M'sian palm oil", New Straits Times - Business Times Online, April 102007, accessed on 10 April 2007, athttp://www.btimes.com.my/Current_News/BT/Tuesday/Frontpage/BT617039.txt/Article/23

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawaktonnes, while the US bought 683,650 tonnes. In 2005, demand from the US rose65 per cent because of the US Government's mandatory labelling of transfatcontent on packaged food by January 1 2006. 28In 2007, the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) was quoted as saying that thetop 10 buyers of Malaysian palm oil in the first six months of 2007 were China(1.6 million tonnes or 14% more than same period last year), the Netherlands,Pak<strong>is</strong>tan (up 23 %), the US, Japan, India (11% more), Singapore, the UnitedArab Emirates, South Africa and South Korea. 29Overall, the European Union bought 875,952 tonnes of palm oil in the first fivemonths of 2007, 17 per cent less than in the same period last year. 30 The EU as awhole <strong>is</strong> an important market for Malaysian palm oil and related products,accounting for 17.9 per cent, or 2.58 million tonnes in 2007. 31With the environmental concerns such as global warming now globallyaccepted, a whole l<strong>is</strong>t of ‘answers’ has been propagated by industries globally.Top among the target areas <strong>is</strong> the fuel industry, and palm-oil has been pushed tothe forefront as the ‘answer’ due to its position in the global oil market. Withindustrialized countries all rushing to set targets for reducing fossil fuel andwhere possible, to replace it with ‘bio-fuel’, the demand <strong>is</strong> anticipated to r<strong>is</strong>esignificantly.All of th<strong>is</strong> translates into substantial interest in the development of palm oilplantations in Sarawak. How does th<strong>is</strong> fit with Sarawak’s own development28 "2006 palm oil exports hit record RM31.8b", New Straits Times - Business Times Online, 11January 2007, accessed on same publication day athttp://www.btimes.com.my/Current_News/BT/Thursday/Frontpage/BT338868.txt/Article/29 ‘Palm oil exports po<strong>is</strong>ed to surpass RM35b th<strong>is</strong> year’, New Straits Times - Business TimesOnline, 27 July 2007, accessed on same publication day athttp://www.btimes.com.my/Current_News/BT/Friday/Nation/35b.xml/Article/30 ‘Malaysian palm oil takes its battle to the air’, New Straits Times Online, 23 June 2007,accessed on same day athttp://www.nst.com.my/Current_News/NST/Saturday/National/20070623095518/Article/index_html31 ‘Malaysia to allay fears in EU over oil palm cultivation’, New Straits Times - Business TimesOnline, 4 June 2007, accessed on same publication day athttp://www.btimes.com.my/Current_News/BT/Monday/Nation/BT625654.txt/Article/24

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakpolicies? Where <strong>is</strong> the land for these expansion plans? How does the lawregulate access to such lands? Whose lands <strong>is</strong> it and what protections are thereof the local communities’ rights? What are peoples’ own experiences of oilpalm development in Sarawak? The following chapters explore some of theanswers to these questions.25

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawak5. Sarawak Government Policies onOil Palm PlantationsSince independence in 1963, successive governments in Sarawak havesupported plantation schemes designed to promote ‘development’ and the moreproductive use of land. Many of the first schemes were with rubber and cacao.The first pilot scheme with oil palm was implemented in 1966. The crops andtechniques may differ but the underlying policy has remained almost constantwhile the State has experimented with a series of initiatives to acquire land andcapital<strong>is</strong>e estates in various different ways. The process began with State-ownedenterpr<strong>is</strong>es on what were considered to be vacant State lands, then moved toState-led ventures on native customary lands, saw a third incarnation as theState’s promotion of private sector ventures on lands unencumbered by theState of prior rights and <strong>is</strong> now in its latest phase, the promotion of jointventures between the private sector, native peoples and the State, in which theState holds native lands in fiduciary trust for development by privatecompanies. None of these schemes has been without problems.The first schemesBetween 1964 and 1974, land resettlement schemes in Sarawak were modelledon the integrated style of development which had been applied in PeninsularMalaysia by the Federal <strong>Land</strong> Development Authority (FELDA) since the mid-1950s. The early schemes in Sarawak were initially carried out by the StateAgriculture Department, and from 1968 to 1972 they were executed by theSarawak Development Finance Corporation. Later (1972 – 1980) these powerswere transferred to a new statutory body, the Sarawak <strong>Land</strong> Development Board(SLDB), which was in turn corporat<strong>is</strong>ed in 1997 as Sarawak Plantation SdnBhd, and which became Sarawak Plantation Berhad in 2000.26

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakAs Bulan has explained, the early schemes involved clearing of new land andthe relocation of natives into resettlement schemes dedicated to the planting ofcash crops, including oil palms. However, although the idea was to developwaste lands, in fact participants in the schemes were often relocated into areaswhere there were already establ<strong>is</strong>hed traditional landowners, and th<strong>is</strong> causedd<strong>is</strong>agreements between scheme participants and the prior owners. To pay fortheir lands, land preparation, planting and initial crop care, the resettled farmerswere burdened with debts that they were meant to repay out of their incomesfrom the crops. However, since these were dependent on the fluctuating pricespaid in world commodity markets, as a result of the declining prices most wereunable to make their repayments. The schemes also lacked the pool of workersand expert<strong>is</strong>e required for their successful implementation and almost all wereeventually abandoned due to management failures. 32 Indeed some of the earliestschemes, such as the Skrang resettlement scheme were principally motivated bynational security considerations and involved the obligatory relocation of IbanDayaks from restive frontier areas to controlled villages. 33 As Jitab and Ritchiehave noted ‘such schemes were doomed from the start’. 34Consolidating customary landsApparently learning from its m<strong>is</strong>takes and accepting the need to take intoaccount customary systems of land tenure, in 1976 the State Governmentestabl<strong>is</strong>hed the Sarawak <strong>Land</strong> Consolidation and Rehabilitation Authority(SALCRA) with the object of developing croplands directly within targetcommunities’ lands. SALCRA was conceived as a joint venture between theState represented by SALCRA and native farmers, in which the participatinghouseholds supposedly retained their rights in land. To qualify, participants hadto already hold suitable land in the proposed area of the scheme and, as owners,32 Bulan 2006, citing King 1988:280 and Ngidang 2001.33 Low level unrest on the frontiers was caused by a number of factors including: PresidentSukarno of Indonesia’s policy of konfrontasi with Malaysia; commun<strong>is</strong>t insurgency and;Sarawakian national<strong>is</strong>t sentiments. <strong>Peoples</strong> such as the Iban, who had a h<strong>is</strong>tory of expansion<strong>is</strong>twarfare, were seen as a threat to the stability of the newly independent State and so were resettled(Colchester 1992:54-57).34 Jitab and Richie 1991:58.27

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakthey were meant to give full consent for the scheme, a condition not strictlyfollowed when SALCRA developed plantations for d<strong>is</strong>placed Iban flooded outby the ADB-funded Batang Ai hydro-electric project. 35The functions of SALCRA included the consolidation and rehabilitation of land,and the prov<strong>is</strong>ion of adv<strong>is</strong>ers and training facilities in various aspects of farmingand land management. SALCRA had responsibility for the establ<strong>is</strong>hment andmaintenance of estates, as well as organ<strong>is</strong>ing, harvesting, processing andmarketing produce during the whole life of the estates. The idea was that oncescheme participants had acquired sufficient know-how to manage lands on theirown, the estate could be divided up among the participating households, thusenabling them to obtain a demarcated piece of land to which they would begranted permanent title. However, in reality, th<strong>is</strong> process of capacity buildingand then d<strong>is</strong>tribution of lands has not been carried through and most schemescontinue to be dependent on government funding and admin<strong>is</strong>tered directly bySALCRA. <strong>Land</strong> d<strong>is</strong>putes in SALCRA areas have been a pers<strong>is</strong>tent problem. 36Bringing in the private sectorThe problems besetting these loss-making para-statal agencies, SLDB andSALCRA, led the government in 1981 to set up the <strong>Land</strong> Custody andDevelopment Authority (LCDA) to promote development projects by theprivate sector. The ‘brainchild’ of the current Chief Min<strong>is</strong>ter, Taib Mahmud, theLCDA has the authority to acquire both state-controlled land and NativeCustomary <strong>Land</strong> for private estate development. It acts as an intermediarybetween landowners and corporations so that private investors can be invited toparticipate in land development subject to an allocation of shares in the relevantcompanies. 37 However, like the SLDB before it, the absence of large areas ofsuitable lands not encumbered with customary rights substantially slowed downthe ability of LCDA to acquire and develop new palm oil estates. In 1991, it35 Colchester 1992: 59-62.36 Jitab and Ritchie 1991; Bulan 2006.37 Jitab and Ritchie 1991; Bulan 2006.28

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakwas estimated that of 2.8 million hectares of land well suited or marginallysuited for agricultural development, only 300,000 hectares were vacant Statelands, 2.5 million hectares being encumbered with native customary rights. 38 In2006, these estimates were rev<strong>is</strong>ed. The Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development,Sarawak now claims to have identified 3.9 million hectares suitable for oil palmcultivation of which only 1.5 million hectares are subject to native customaryrights. 39Although these schemes in Sarawak were initially modelled on the broadlysuccessful land development programmes implemented by FELDA in thePeninsula, they were not well adapted to the realities of rural Sarawak. FELDAschemes on the Peninsula settle landless families on forested State lands, whichare then cleared, typically for planting rubber and oil palm. In Sarawak, mostlands are not vacant lands unencumbered of rights, most community membersare far from landless, most pract<strong>is</strong>e diverse livelihood strategies and combineseveral economic options and most have much more limited experience with,and access to, markets. Moreover, estates require cheap labour to functionprofitably in a highly competitive world market, but in Sarawak localcommunity members are reluctant to work for such low wages, especially whenmore lucrative jobs are available, such as in the logging camps. 40 Indeed mostprivate sector oil palm estates in Malaysia depend on low paid migrant labour.With unencumbered State lands in short supply yet customary lands hard tomanage, the government had to find a new way to gain access to native peoples’lands for plantations developmentThe ‘New Concept’In 1994, therefore, the Chief Min<strong>is</strong>ter announced a ‘New Concept’ (KonsepBaru) for the development of plantation lands, which brought together ‘nativecustomary rights landowners with their land and the private sector with theircapital and expert<strong>is</strong>e’. The new approach had the twin aims of, on the one hand,divesting the State of its financial r<strong>is</strong>ks in plantations development by38 Jitab and Ritchie 1991:66.39 Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development, nd.40 Jitab and Ritchie 1991:57-59.29

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakencouraging direct investment by the private sector, while, on the other hand,providing a mechan<strong>is</strong>m to acquire customary lands and make them securelyavailable in large blocks of over 5,000 hectares so they were attractive todevelopers.Under the Konsep Baru companies buy a 60% share in a joint venture,communities are allocated a 30% share in recognition of their contribution oflands, while the State acquires the remaining 10%. The State, by virtue of itsfiduciary role and its responsibilities towards both investors and thecommunities, represented by a State agency such as the LCDA or Pelita, holdsthe communities’ 30% stake in trust. 41 The lands are then leased to the jointventure company for 60 years, being two full cycles of oil palm development. 42Why should the State take on the role of Trustee over the communities’ land?According to the Min<strong>is</strong>try for <strong>Land</strong> Development which <strong>is</strong> tasked withimplementing the Konsep Baru, th<strong>is</strong> arrangement <strong>is</strong> favoured because it ‘willgive absolute right to the implementing company to manage the plantationWITHOUT interference from the NCR landowners over a period of 60 years’. 43During those 60 years, the landowners’ interest in the plantation <strong>is</strong> representedentirely by the State agency that acts as Trustee for the native people.Participating farmers thus have no direct voice in the management of theschemes but can expect to be paid the equivalent of about M$ 1,200 for eachhectare of land surrendered to the scheme, although of th<strong>is</strong> amount 60% <strong>is</strong> usedto acquire shares in the joint venture and another 30% <strong>is</strong> held onto by theTrustee and invested in Government Unit trusts, while only 10% - about M$120(approx. US$33) - <strong>is</strong> paid in cash to the landowner. No compensation <strong>is</strong> payablefor any ex<strong>is</strong>ting crops, fruit trees or improvements on the land, but participatinglandowners can later expect to be paid an annual shareholder dividend41 In the words of the Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development’s website: ‘In order to facilitate theformation of such joint-ventures and to safeguard the interests of both the landowners and theinvestor, the State Government will appoint its agency such as LCDA as Trustee to manage theinterests of the landowners’, Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development nd.42 Majid Cooke 2002, 2006; Bulan 2006; Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development nd.43 Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development, nd, pdf on website titled ‘Issues and Responses’ page 1,emphas<strong>is</strong> in original.30

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakproportional to the amount of land they contributed to the scheme in the firstplace, from which may be subtracted any costs incurred if the total value of thelands surrendered <strong>is</strong> calculated to be less than the value of the communities’30% equity in the company. 44Responsibility for dealings with the local communities in setting up theseprojects <strong>is</strong> given to the Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development, currently led by a DayakMin<strong>is</strong>ter, James Masing. The Min<strong>is</strong>try has been tasked with the goal of buildingup a ‘land bank’ of 1 million hectares including at least 400,000 hectares ofnative customary lands to be acquired at a rate of at least 60,000 hectares peryear. 45 According to the Min<strong>is</strong>try, the objective <strong>is</strong>:To promote the commercial development of the idle andunderutilized NCR land and the orderly development of state landinto oil palm plantations in order to create employment opportunitiesin the rural areas and thereby ensuring (sic.) sustainable source ofincome in the rural areas. Ultimately, land development, particularlythe NCR land development, should ra<strong>is</strong>e the standard of living of therural people and contribute towards poverty eradication, reduce ruralurbanmigration and result in a balanced development between therural and the urban areas. 46With buoyant prices for Crude Palm Oil on the international markets, boosted inrecent months by speculation in biofuels, the Konsep Baru has been successfulin attracting private sector investment into the oil palm sector in Sarawak.Whereas in 1991, the great majority of palm oil estates in Sarawak were ownedor controlled by para-statals, by 2002 only some 17% of plantations were Statecontrolled,the rest being held by private companies. 47 By the end of 2005, theMin<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development announced that under the Konsep Baru approach44 Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development, nd, pdf on website titled ‘Issues and Responses’ pages 3-4. It <strong>is</strong>not clear how land values are calculated given the absence of markets in land in most NCR areas.45 Recently it was reported that in order to achieve the target of 1 million hectares by 2010, theState government <strong>is</strong> now committed to planting oil palm on at least 100,000 hectares per year,Borneo Post, August 8 th , 2007, page. 8.46 Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development nd.47 Majid Cooke 2002.31

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawakthere were already 31 land development projects on Native Customary <strong>Land</strong>s invarious stages of development covering a total area of 248,337 hectares, out of atotal area under oil palm by the same date of 543,399 hectares. A further 65Konsep Baru projects are planned. 48Ostensibly in order to avoid confusion over lands and to avoid unrepresentativeleaders from doing deals direct with investors, the Konsep Baru prohibits directnegotiations between communities and investors and requires State agencies tomediate in matching community lands with companies. Companies interested indeveloping plantations first have to file an application to the Min<strong>is</strong>try with adetailed investment and land development plan. The lands of interest to thecompany must then be surveyed by the State’s <strong>Land</strong>s and Surveys Departmentto verify the extent of areas under Native Customary Rights. <strong>Land</strong>s and Surveysthen draws up maps which show the external boundaries of NCR areas and alsokeep records of which individuals hold approximately how much land withinthe block. <strong>Land</strong> rights allocations within the blocks are handled by an AreaDevelopment Committee which compr<strong>is</strong>es the penghulu (chief) and theheadmen of participating villages. 49 Any d<strong>is</strong>putes over land betweencommunity members are to be resolved by native courts.The scheme <strong>is</strong> still too new for there to be actual experiences with the expiry ofthe sixty year leases. According to the official documentation, for the period ofthe lease all the lands are held under a single land title retained by the privatesector company as majority shareholder of the joint venture. The land, which <strong>is</strong>only to be used for agricultural purposes, can only be transferred to anotherparty with the express perm<strong>is</strong>sion of the Min<strong>is</strong>ter for <strong>Land</strong> Development, whilethe community members’ shareholdings (and future rights in returned lands)can only be transferred to close kin. However, on expiry of the lease, thecustomary owners may either decide to renew the arrangement with the same oranother company, or take the land back under communal ownership, or havethe land subdivided and titled to the original owners as individual landholdings. 5048 Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development nd.49 Penghulu and village headmen (tua kampong) are positions recogn<strong>is</strong>ed by government. Theygain a modest stipend for their role in the local admin<strong>is</strong>tration.50 Min<strong>is</strong>try of <strong>Land</strong> Development nd.32

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakAcademic studies of the implementation of the Konsep Baru have pointed out anumber of weaknesses in the scheme. A study by Majid Cooke, publ<strong>is</strong>hed in2002, found that communities’ reactions varied from region to region.Downstream communities that had benefited from previous State developmentschemes such as road building and service prov<strong>is</strong>ion tended to be more trustingof the government’s role and more welcoming of the concept, while uprivercommunities that had suffered from the imposition of logging on theircustomary rights areas were much more suspicious of the government’smotives, were sceptical about the reality of prom<strong>is</strong>ed benefits and so rejectedthe schemes.The study noted that many Dayak groups sought to head off the takeover oftheir lands by Konsep Baru projects by themselves strategically planting oilpalms or other crops along the boundaries of their customary lands, both toassert their rights in land and demonstrate that the land <strong>is</strong> already productive.Dayaks interviewed in the study were sceptical of the impartiality of thegovernment agencies acting as trustee for the people, concerned about thepossible impacts of market fluctuations and worried by exactly how and withwhat legal entitlements their lands would be returned to them after the expiry ofthe 60 year leases. 51A further study by Majid Cooke has interpreted the Konsep Baru as a schemefor extending State power over ‘backward’ Dayak groups. Majid Cooke arguesthat the whole concept <strong>is</strong> based on a ‘fundamental error, ar<strong>is</strong>ing from am<strong>is</strong>interpretation of unoccupied land as ‘idle’ or ‘waste’ land’. 52 Furtherconcerns about the schemes were voiced in a series of hearings held bySUHAKAM, the Malaysian Human Rights Comm<strong>is</strong>sion, in 2004 and 2005.Press accounts summar<strong>is</strong>ed by Majid Cooke noted that at these hearings Dayaksra<strong>is</strong>ed a number of questions about the Konsep Baru, complaints focusing onthe frequent encroachments on their lands, the slugg<strong>is</strong>h pace and defectiveprocedures used to survey their lands since the passing of the rev<strong>is</strong>ed <strong>Land</strong>51 Majid Cooke 2002.52 Majid Cooke 2006:27.33

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in SarawakCode Amendment in 2000 and the unfair limitations on their right to buy andsell their lands. 53According to another study, many of the officials implementing the schemesthemselves do not really understand the legal and economic implications of theKonsep Baru. 54 Majid Cooke found that, when Dayaks pressed forexplanations of the full implications of their involvement in projects that theywere being invited to join, they were labelled as ‘anti development’, excludedfrom subsequent public meetings and left out of further dec<strong>is</strong>ion-making. Insome cases the schemes then went ahead on their lands regardless, leading todirect clashes as bulldozers moved in on the lands of those who had come tooppose the projects. 55A further review by Bulan, found that many people participated in the pilotKonsep Baru projects in Baram and Kanowit d<strong>is</strong>tricts ‘without a fullunderstanding of what such alien concepts as the trust, joint venture, or sharesin the company entailed’. He also notes the r<strong>is</strong>ks that the government’s roles asa trustee could be abused by a conflict of interest, as both a promoter of privatesector interests and guardian of the interests of the native landowners.Moreover, under Engl<strong>is</strong>h common law traditions, trustees are not meant to havea financial interest in the assets they manage on behalf of their wards. 56 Underthe Konsep Baru, the State takes a 10% interest, agency personnel areemployed to further the schemes and 30% of monies paid for surrendered landsare invested in Government unit trusts. Bulan concludes that further safeguardsof native rights are needed if conflicts are to be prevented, one solution beingthat instead of prom<strong>is</strong>ing title to landowners on the expiry of the lease, theirrights in land should be clearly titled before they decide whether or not toengage in a joint venture. 5753 Majid Cooke 2006:30.54 Majid Cooke 2002 citing Ngidang 2002.55 Majid Cooke 2002: 40-41.56 Bulan 2006:53-54.57 Bulan 2006:45, 61.34

<strong>Land</strong> Rights and Oil Palm Development in Sarawak6. Oil Palm Plantations in the CourtsIndeed, conflicts between native peoples claiming customary rights in landsand imposed development schemes have been a long term problem inSarawak. 58 According to press accounts there are currently some 150 cases inthe courts of Sarawak relating to such d<strong>is</strong>putes. Of these we have been able toidentify about 100 cases filed by native plaintiffs, 40 of which are cases thatinclude charges against oil palm developers. (The map below shows thelocations of about one third of all these cases).58 Hong 1987; Colchester 1992.35