With God's Camel in Siberia - Jerusalem Quarterly

With God's Camel in Siberia - Jerusalem Quarterly

With God's Camel in Siberia - Jerusalem Quarterly

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>The Russian Exile of anOttoman Officer from<strong>Jerusalem</strong>Salim TamariFirst Lieutenant Aref Shehadeh, RussianIdentity Card for Ottoman Prisoners 1915.Source: Aref Family Papers.The late Ottoman period and the earlycolonial Mandates (French and British)witnessed the appearance of a type ofpolitical advocate/public <strong>in</strong>tellectualthat all but disappeared dur<strong>in</strong>g the later<strong>in</strong>dependence period. This type of activistwas then replaced by a new breed of public<strong>in</strong>tellectual—the professional party activist(Ba’th, Nasserite, Syrian Nationalist,and communist), and by the ‘committed<strong>in</strong>tellectual’ of the 1950s, and 1960s—<strong>in</strong>tellectuals who were active with<strong>in</strong> or <strong>in</strong>the marg<strong>in</strong> of those political parties. Anoutstand<strong>in</strong>g example of this earlier type ofengaged scholar was Abu Khaldun Sati alHusari (1881-1967) the Syrian theoreticianof Arab nationalism and author of thesem<strong>in</strong>al A Day <strong>in</strong> Maysalun—a treatiseabout the defeat of the first unitary ArabState <strong>in</strong> modern times. Husari’s life spanshis <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> the late Ottoman reformsand the establishment of the CUP of whichhe was a found<strong>in</strong>g member <strong>in</strong> 1905. 1<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 35 [ 31 ]

Aref Effendi as translator <strong>in</strong> the Ottoman Foreign M<strong>in</strong>istry. Istanbul 1913. Source: Aref Family Papers.[ 32 ] <strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>

Husari’s <strong>in</strong>tellectual and political career marks, and played an <strong>in</strong>fluential role <strong>in</strong> thetransition from Ottomanism to Arabism.What dist<strong>in</strong>guished these public <strong>in</strong>tellectuals of the early period was their <strong>in</strong>volvement<strong>in</strong> the public sphere without the benefit of mass political parties or movements. Theirpath of engagement <strong>in</strong> political action was their literacy (conf<strong>in</strong>ed to an urban elite),their writ<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> nascent nationalist presses, their membership <strong>in</strong> literary societies andclubs (al Muntada al Adabi, the Vagabond Café, al Urwa al Wuthqa), and—for quite afew—tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Ottoman military academies and service dur<strong>in</strong>g WWI <strong>in</strong> the Ottomanarmed forces. The imperial military schools were significant conduits for establish<strong>in</strong>ga network of collaboration between members of the various ethnic communities<strong>in</strong> the Ottoman period. For a brief period (1908-1914) it was also a crucible ofsocialization <strong>in</strong>to a reconstituted Ottoman citizenship. Almost without exception these<strong>in</strong>tellectuals served as public officers <strong>in</strong> the civil service of the Ottoman and (later<strong>in</strong>) the French and British Mandate adm<strong>in</strong>istration. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the Constitutional periodof 1908, the Ottoman bureaucracy was much more fluid than its British and Frenchcolonial regimes, and allowed for considerable advancement for sections of the urbanliterate strata, at least <strong>in</strong> as far as the ability of prov<strong>in</strong>cial bureaucrats to belong tovarious political parties, and to express dissident op<strong>in</strong>ions. Their membership <strong>in</strong> thesegovernment positions did not, <strong>in</strong> the most co-opt them <strong>in</strong>to acquiescence, nor did itco-opt their role as public advocates of Arab unity, social progress, and for quite a fewa radical opposition to the central authority.One only has to name few of such figures to recognize the disappearance of their type:Sati al Husari (Aleppo, Istanbul and Baghdad), Rustum Haidar (Baalback), Ruhi alKhalidi (Istanbul and <strong>Jerusalem</strong>), Muhammad Izzat Darwazeh (Nablus and Beirut),Muhammad Dia al Khalidi (Istanbul and <strong>Jerusalem</strong>), Khalil Sakak<strong>in</strong>i (Damascus and<strong>Jerusalem</strong>), and Falih Rifki Atay (Istanbul, Damascus, and <strong>Jerusalem</strong>).In this essay I will exam<strong>in</strong>e the early career of officer Aref Shehadeh, 1892-1973 (laterknown as the historian Aref al Aref) 2 whose public life spanned the late Ottoman,Mandate, Jordanian, and Israeli rules over Palest<strong>in</strong>e. S<strong>in</strong>ce much of what he laterwrote (histories, essays and diaries) constructed a nationalist discourse that was atvariance with his earlier activities (and utterances) dur<strong>in</strong>g World War I and the pre-warperiod, my purpose here is to re-exam<strong>in</strong>e this earlier period <strong>in</strong> order to understand howboth the etymologies and trajectories of Syrian and Palest<strong>in</strong>ian nationalism evolved.S<strong>in</strong>ce Aref spent most of the war period (1915-1918) <strong>in</strong> Russian exile (which is thefocus of this article), his <strong>Siberia</strong>n experience sheds new light on these transformations.Like Husari, Aref shared an early elite education <strong>in</strong> Istanbul, a loyal aff<strong>in</strong>ity for theOttoman regime, and membership, or sympathy for, the CUP (the Young Turks). LikeHusari, he defected from his Ottoman loyalties at the end of the war to jo<strong>in</strong> the SyrianNational movement under Pr<strong>in</strong>ce Faisal. Both served as civil servants <strong>in</strong> the British<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 35 [ 33 ]

Mandates (Husari <strong>in</strong> Iraq, Aref <strong>in</strong> Transjordan and Palest<strong>in</strong>e), but whereas Husaribecame a ma<strong>in</strong> advocate and theoretician of Arab nationalism, Aref acclimatizedhimself to the fragmentation of the post war Arab East, and played an active role <strong>in</strong>both the creation of Transjordan as a separate state, and <strong>in</strong> the public adm<strong>in</strong>istration ofMandate Palest<strong>in</strong>e.Most of what we know about his earlier career comes from biographic fragments thathe wrote, and later re-wrote. Born <strong>in</strong> <strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>in</strong> 1892 he was sent by his familyto Istanbul to f<strong>in</strong>ish his secondary school<strong>in</strong>g. He later studied literature at IstanbulUniversity, receiv<strong>in</strong>g his first degree <strong>in</strong> 1913. Upon graduation he worked as a nighteditor <strong>in</strong> the Turkish daily, Bayam.In Istanbul he jo<strong>in</strong>ed (and accord<strong>in</strong>g to Awdat, he was one of the founders of) alMuntada al Arabi (the Literary Forum) which was a meet<strong>in</strong>g club for Lebanese,Syrian and Palest<strong>in</strong>ian <strong>in</strong>tellectuals from Bilad al Sham. 3 After graduation fromIstanbul University, Shehadeh was appo<strong>in</strong>ted as a translator <strong>in</strong> the Ottoman M<strong>in</strong>istryof Foreign Affairs. <strong>With</strong> the eruption of the Great War he enlisted <strong>in</strong> the MilitaryCollege <strong>in</strong> Istanbul, and upon graduation he was conscripted as an Ottoman officer<strong>in</strong> the Radif (Reserve) Forces, and later <strong>in</strong> the Fifth Army and fought on the RussianFront. There he was captured and spent three years <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong> as a prisoner of war,before he was liberated by the onset of the Bolshevik Revolution. He returned byland via Manchuria and Japan where he jo<strong>in</strong>ed the ranks of the Arab Rebellion underthe leadership of Pr<strong>in</strong>ce Faisal. In <strong>Jerusalem</strong> after the war he published and editedthe Faisali organ, Southern Syria. He was sentenced to death by the British for hissupport of armed resistance to the British, and later commuted to imprisonment andexile. Aref eventually returned and undertook a number of public positions, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gQa’imaqam of Beersheba and Gaza. In the late twenties he became Secretary ofthe Adm<strong>in</strong>istrative Council of Transjordan, which made him a keen observer of thegenesis of the Hashemite K<strong>in</strong>gdom. His unpublished memoirs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong> (1915-1918),and Transjordan (1926-29) constitute a fabulous w<strong>in</strong>dow to a vanished era. Theseworks should be contrasted with the ‘authorized’ version of Aref’s early biography,based on his post-war memoirs. 4 We will now exam<strong>in</strong>e the divergence and conflicts<strong>in</strong> these two sets of biographical texts (the early memoirs, and later autobiographicaltracts) aga<strong>in</strong>st the historical record.Early Education: I found my Arabness <strong>in</strong> IstanbulAref Shehadeh received his early education <strong>in</strong> al Ma’muniyyeh Intermediate School.On the eve of Sultan Abdul Hamid’s overthrow <strong>in</strong> 1909, when Aref was barely sixteen,his father Shehadeh Ibn Abdul Rahman Ibn Mustafa al Aref, a prom<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>Jerusalem</strong>merchant <strong>in</strong> the old city, sent his middle son Aref to Istanbul (“the Qibla of Arab,[ 34 ] <strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>

Lieutenant Aref, on graduation from Military Academy<strong>in</strong> Istanbul 1914. Source: Aref Family Collection.Turkish, Armenian, Kurdish, Greek,and Albanian youth, as he called it”) 5to receive his higher education. Infive (1908-1913) condensed years hewas able to f<strong>in</strong>ish his school<strong>in</strong>g at theMaktab Sultani, known as Namu’ahTaraqi, and at Istanbul University,where he received a literature degree<strong>in</strong> 1913. While study<strong>in</strong>g he workedas a night editor <strong>in</strong> the Turkish dailyBayam to support his education. 6Aref’s assertion of Arabism for thisperiod is retrospectively portrayedas a belief <strong>in</strong> a separatist futurefor the Arab nation. By exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ghis earlier writ<strong>in</strong>gs and personalpapers we get a different picture. AlMuntada al Adabi, which he belonged to <strong>in</strong> Istanbul, and accord<strong>in</strong>g to some sourceswas a co-founder along with Abdul Karim al Khalil, 7 was a product of the 1908constitutional revolution, and most of its members where firm believers <strong>in</strong> Ottomandecentralization—not secession— from Istanbul. 8 His enlistment <strong>in</strong> the MilitaryCollege, and subsequent military career as an officer <strong>in</strong> the Fifth Army (which hecould have avoided by pay<strong>in</strong>g the badal) suggest that he was more than a neutralbeliever <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>tegrity of the Ottoman regime. His fluency <strong>in</strong> Turkish advanced hiscareer <strong>in</strong> the Ottoman bureaucracy, but also stamped him with <strong>in</strong>tellectual aff<strong>in</strong>ities forits Ottoman culture. Of his self-discovery of his Arab identity this is what he wrote <strong>in</strong>his diary:I was not aware that I was an Arab, and that I should th<strong>in</strong>k of the future ofmy Arab nation until the establishment of the Literary Forum (al Muntadaal Adabi) <strong>in</strong> Istanbul. Of the founders I remember four names: Abdul Karimal Khalil, Yusif Mukhaibar, Jamil al Husse<strong>in</strong>i, and Seiful D<strong>in</strong> al Khatib. Iwas registered as a member and was s<strong>in</strong>ce then engulfed with the prevail<strong>in</strong>gArab nationalism among the students. It was then that I began to hear thewords Arabs, Arabism, Nationalism, and Homeland. 9This was written after the war. It is more likely, however, that the crucialtransformation <strong>in</strong> Aref’s career and consciousness occurred not dur<strong>in</strong>g his universityyears, as he professed <strong>in</strong> the commissioned biographical essay published by Yacoub alAwdat, or dur<strong>in</strong>g his Istanbul journalistic period, and almost certa<strong>in</strong>ly not dur<strong>in</strong>g hiswork at the Ottoman Foreign M<strong>in</strong>istry, where he seemed to be a ris<strong>in</strong>g bureaucrat <strong>in</strong>the system. 10 Rather it is most likely that the radical break with Ottomanism occurred<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 35 [ 35 ]

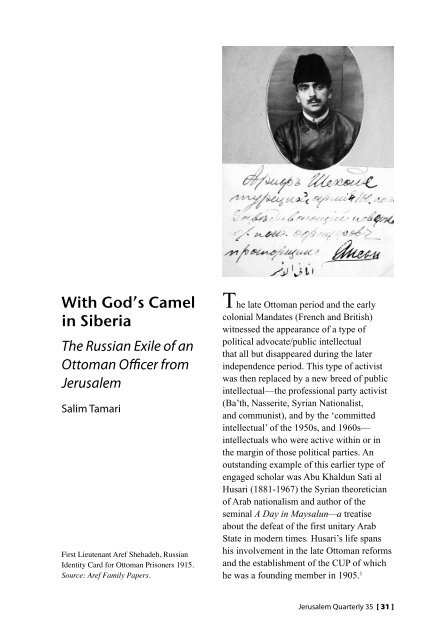

Issue No. 35 of Naqat Allah, dated Krasnoyarsk, <strong>Siberia</strong> Friday 29 Aylul 1333 Ottoman Calender, equiv.to 25 Dhil Hijja 1335 Hijri (1916).dur<strong>in</strong>g his Russian captivity <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>. In Istanbul Aref was a member of the LiteraryClub (al Muntada al Adabi), and was very close to its head Abdul Karim al Khalil.Al Khalil was <strong>in</strong> turn affiliated to the conciliatory w<strong>in</strong>g of the Ottoman Party ofDecentralization (OPD), which counseled unity with the CUP. We have no evidence ofAref belong<strong>in</strong>g to either of these parties, but with the entry of Istanbul <strong>in</strong>to WWI onthe side of the Central Powers (Germany and Austria), al Khalil and the Literary Clubtook a position of support<strong>in</strong>g the state and suspend<strong>in</strong>g their demands for reform <strong>in</strong> theArab prov<strong>in</strong>ces lest it be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as a form of secessionism. 11 Dur<strong>in</strong>g the courseof the war however, its members began to feel the pressures of the countervail<strong>in</strong>gtendencies that divided the CUP and OPD, and pushed at least a section of OPD, thenbased <strong>in</strong> Cairo, to fight for <strong>in</strong>dependence from the Empire.<strong>Siberia</strong>n ExileShehadeh had just graduated from military college when he was conscripted and sentto fight aga<strong>in</strong>st the Russians <strong>in</strong> the Caucasian front. He was captured after a bloodybattle <strong>in</strong> Ard al Rum (Erzerum), <strong>in</strong> which most of his regiment was wiped out, withonly eleven soldiers surviv<strong>in</strong>g. 12Shehadeh narrates his <strong>Siberia</strong>n experience <strong>in</strong> a little known autobiographic text,Ru’yaii (‘My Vision’), written <strong>in</strong> December 1918, immediately after his escapefrom prison camp <strong>in</strong> the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution. 13 The march of Ottomanprisoners to <strong>Siberia</strong> was atrocious. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Turkish historian Yucel Yanikdag onlyone <strong>in</strong> four Ottoman prisoners captured <strong>in</strong> the w<strong>in</strong>ter of 1915 reached their dest<strong>in</strong>ation.[ 36 ] <strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>

Aref Shehadeh Letter received <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong> from his brother Suleiman–sent from <strong>Jerusalem</strong> on 27th of July,1916. Received <strong>in</strong> Krasnoyarsk, <strong>Siberia</strong> on August 20 th , 1916. Source: Osmanli sahra postaları, Istanbul,2000.The rest perished from hunger and disease on their forced march to the camps. 14 Thiswas a much higher ratio than European prisoners taken by the Russians on the Easternfront. 15 This is confirmed <strong>in</strong> Shehadeh’s own diary:We were taken to ma<strong>in</strong> camp <strong>in</strong> Krasnoyarsk (Красноя́ рск), near the shoresof the Yenisei river (Енисе́ й) <strong>in</strong> central <strong>Siberia</strong>. I spent three years <strong>in</strong> a special<strong>in</strong>ternment camp, Wyuni Gorodok where the food conditions and cold wereunbearable. The camp was surrounded by an iron fence and barbed wire.Armed soldiers watched us day and night to prevent our escape. But also toprevent us from observ<strong>in</strong>g the life of ord<strong>in</strong>ary Russians who were suffer<strong>in</strong>gfrom Tsarist desptism. 16Once the Ottomans prisoners settled <strong>in</strong> the camp, controls became more lax andrecreational facilities improved. By the second year he was able to report:There were 3,500 prisoners <strong>in</strong> our camp. We had several fields to exercise <strong>in</strong>.One for football games, another for runn<strong>in</strong>g exercises, and a third for othersports activities. We had a large hall <strong>in</strong> which we organized lectures andtutor<strong>in</strong>g; a little theatre, and a substantial library. Later on I was able to putout a satirical newspaper, without authorization, for my fellow soldiers. 17Throughout his imprisonment Aref was able to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> contact with his familythrough correspondence adm<strong>in</strong>istered by the Ottoman Red Crescent. Letters written <strong>in</strong>Turkish and French to and from his father and brother Suleiman <strong>in</strong> <strong>Jerusalem</strong> survive.Because of military censorship (Russian, Austrian, and Ottoman) the exchanges<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 35 [ 37 ]

Col. Karol Riba, The Polish officer <strong>in</strong> the Tsarist armywho became Shehadeh’s benefactor <strong>in</strong> Krasnoyarsk.Source: AFP.were conf<strong>in</strong>ed to enquiries about thefamily’s health, and mundane newsabout camp life. But he kept closecontacts with the developments <strong>in</strong> thehome front. We learn from them thathis brother Suleiman was study<strong>in</strong>g atthe Salahiyyeh College, which JamalPasha had established with the aimof recruit<strong>in</strong>g young civil servants forthe Ottoman bureaucracy, and abouthis cont<strong>in</strong>ued requests for Arabicnewspapers and journals to be sent tohim <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>. 18 The requests <strong>in</strong>dicatethat packages where arriv<strong>in</strong>g to theKrasnoyarsk (Красноя́рск) throughthe work of the Swedish Red Cross.Eventually Aref was able to obta<strong>in</strong> amilitary pass to leave the camp dur<strong>in</strong>gthe day, arranged by a Polish officer<strong>in</strong> the Tsarist army, Colonel KarolRiba, who wanted Shehadeh to teach him Turkish. This allowed Aref to earn somemoney, and—for a period—to move <strong>in</strong>to an apartment <strong>in</strong> Krasnoyarsk. Photographsthat survived from this period <strong>in</strong>dicate that he had several Russian friends, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gyoung women, who <strong>in</strong>vited him to their home. Several pictures show him celebrat<strong>in</strong>gnew year and other occasions. Inside the <strong>in</strong>ternment camp he was able to studyRussian and German. His German became well developed for him to translate <strong>in</strong>toTurkish, and publish <strong>in</strong> 1917 Die Welträtsel (The Riddle of the Universe) by theGerman philosopher and Darw<strong>in</strong>ian scientist Ernst Haeckel.Peter Gatrell, who exam<strong>in</strong>ed studies on WWI POWs of the Central Powers <strong>in</strong> Russiamade the observation that war <strong>in</strong>carceration provides a w<strong>in</strong>dow for study<strong>in</strong>g theundisclosed consequences of prison experience which <strong>in</strong>clude “solidarity, personaland group identity, and the psychological consequences of conf<strong>in</strong>ement”. 19 Exile andcaptivity were often seen as a ‘voyage of self-discovery’. 20 Here I will <strong>in</strong>vestigate <strong>in</strong>particular the second of these consequences as it affected Arab (Syrian) prisoners. Themost comprehensive study of Ottoman prison conditions <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong> was undertaken byYucel Yanikdag. 21 It confirms much of what Lieutenant Shehadeh has written about <strong>in</strong>his diary eighty years earlier, but it also provides a wider context of events <strong>in</strong>side thecamps. One ma<strong>in</strong> reason why prisoners were separated along ethnic categories had todo with work <strong>in</strong>centives. S<strong>in</strong>ce the Russians employed most of the rank and file POWsto work <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>es, railroads and digg<strong>in</strong>g canals, they assumed that prisoners workbetter <strong>in</strong> an environment of ‘common culture’. 22[ 38 ] <strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>

favoritism to the Arabs could be viewed as a negative reaction to the sympathies ofTurkic Russian communities <strong>in</strong> the vic<strong>in</strong>ity of the camps towards the imprisonedTurkish soldiers, but it is more likely that the Tsarist government, the military ally ofEntente powers <strong>in</strong> the war, was foster<strong>in</strong>g a potential patronage of Arab recruits as partof its imperial strategy <strong>in</strong> the Middle East.Yanikdag confirms the picture drawn by Shehadeh on the rich and versatile socialactivities <strong>in</strong> Krasnoyarsk (Красноя́рск), and other <strong>Siberia</strong>n camps. 27 Officers hadorganized a number of musical concerts and theatrical groups. Sports clubs andfootball teams, play<strong>in</strong>g along national l<strong>in</strong>es, mushroomed. Hungarians, Austrianand Ottoman teams competed aga<strong>in</strong>st each other. Each major camp had its ownlibrary, usually organized by the Swedish Red Cross and the YMCA. Hand pr<strong>in</strong>tednewspapers were also circulat<strong>in</strong>g, both <strong>in</strong> Arabic and Turkish:…every large camp had an Ottoman newspaper at one time. In Krasnoyarsk,for example a paper called Kurtulus (Liberation) was quite popular with theprisoners. It featured not only news from home and about the war, but alsoarticles on the ethnography of Central Asia and the history of the Turkicpeoples. It seems that some of the most popular articles and editorials werenationalistic <strong>in</strong> nature, po<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g to the appeal of Turkish nationalism amongthe officers. 28It is quite likely that the success of Kurtulus, and its emphasis on a Turkish nationalistidentity triggered the creation of Naqatu Allah (God’s <strong>Camel</strong>), an Arabic hand-writtenpaper published <strong>in</strong> Krasnoyarsk. Naqatu Allah was published clandest<strong>in</strong>ely amongSyrian soldiers <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>—“one-third satire, and two thirds politics”, <strong>in</strong> Aref’s words,“how difficult prison life would be without a farcical side”. He edited the paper witha fellow prisoner from Syria, Ahmad al Kayyali. Forty-five issues were publishedbetween Rajab 1335 (1916) and Jamadi al Thani 1336 (1917). The paper’s mastheaddisplayed a camel lost <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Siberia</strong>n tundra and announced the journal as a ‘literary,critical, satirical weekly’, published <strong>in</strong> Krasnoyarsk and Divnogorsk (Дивного́ рск34 km. west of Krasnoyarsk). Each issue sold for 3 kopeks, and a year’s subscriptionwas one ruble. Commercial advertisements were accepted at five kopeks per l<strong>in</strong>e. Thepaper even listed an (obviously fake) telephone “number 49”. 29 It is strik<strong>in</strong>g that Arefand Kayyali chose a Qur’anic image for their paper, given the former’s thoroughlysecular credentials at the time. Naqat Allah (God’s <strong>Camel</strong>) refers to the miracleenacted by God when the Prophet Saleh was challenged <strong>in</strong> the desolation of the desertto produce a camel that gives milk, and God responded to his prayers <strong>in</strong> order tosilence his doubters. 30 But it does confirm Yanikdag’s claim that Islamic imagery wasa bond<strong>in</strong>g factor among prisoners, even though a m<strong>in</strong>ority of the camp residents (30out of 400 officers) fasted dur<strong>in</strong>g the month of Ramadan. 31[ 40 ] <strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>

The Bolshevik Factor: Escape from Revolution or Liberation?The context for Shehadeh’s escape from <strong>Siberia</strong> was the Bolshevik Revolution. In hisaffidavit to Yacoub al Awdat, Aref Shehadeh gives this account for his escape from<strong>Siberia</strong> (<strong>in</strong> the third person). “Dur<strong>in</strong>g the last year of his captivity news began toarrive of Sheriff Husse<strong>in</strong> b<strong>in</strong> Ali’s Rebellion aga<strong>in</strong>st Turkish rule. Aref prevailed ontwenty-one of his fellow Arab prisoners to escape <strong>in</strong> order to jo<strong>in</strong> the Arab rebellion.They took the route of Manchuria, Japan, Ch<strong>in</strong>a, India, and Egypt through the RedSea. Dur<strong>in</strong>g this arduous journey the Armistice was declared.” 32 This paragraph istaken verbatim, with very slight changes, from his Autobiographic Notes, published <strong>in</strong>1964. 33 Surpris<strong>in</strong>gly there is no mention here of neither the Bolsheviks nor the Octoberevents <strong>in</strong> these later versions of his writ<strong>in</strong>gs.But the ‘escape’ story needs to be seen <strong>in</strong> the context of the chaos produced <strong>in</strong> theprison camps by the revolution, which happens to ‘co<strong>in</strong>cide’ with the Arab officersleav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Siberia</strong>. In his ‘visionary’ text written <strong>in</strong> 1918, he referred to the hardships ofprison life <strong>in</strong> Krasnoyarsk, he adds the follow<strong>in</strong>g sentence which does not appear <strong>in</strong>any subsequent text about <strong>Siberia</strong>:“…this was the situation dur<strong>in</strong>g the era of Tsar Nicholas the Second, beforethe outbreak of the Bolshevik Revolution, which broke out throughout thecountry, and spread anarchy and fear. Matters went out of control [<strong>in</strong> ourcamp] and we had to start to scavenge for our food <strong>in</strong> the woods and thewilderness to secure our liv<strong>in</strong>g. This situation cont<strong>in</strong>ued until we receivednews of the Great Arab Revolt and the Insurrection of Husse<strong>in</strong> Ibn Aliaga<strong>in</strong>st the Turks”. 34Aref’s daughter also confirms <strong>in</strong> her recollections of her father’s life that he ‘escapedwhen the Bolsheviks came to power’. 35 She also adds that her father recalled the arrestand execution of Tsar Nicholas and his family <strong>in</strong> an area close to his encampment. 36It is worth exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g this absence <strong>in</strong> detail because, <strong>in</strong> my view, it is related to Aref’snew nationalist consciousness and his break with Ottomanism, a process which beganwith ethnic segregation <strong>in</strong>side the camps and the publication of Naqat Allah. Dur<strong>in</strong>gthe 1917-1918 periods, adm<strong>in</strong>istrative chaos spread throughout Russia. The situation<strong>in</strong>side the camps was even more acute as, “the exit<strong>in</strong>g agencies for POW relief andrepatriation struggled to survive and cope with the displaced persons scattered acrossthe dis<strong>in</strong>tegration tsarist empire.” 37It was <strong>in</strong> this atmosphere that the Arab prisoners escaped, or, depend<strong>in</strong>g on one’sperspective, were liberated, to return to their homeland.<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 35 [ 41 ]

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Yucel Yanikdag theissue was much more complex, s<strong>in</strong>ce“…when the Bolsheviks came topower, they declared the POWs freecitizens and guests of the Russianpeople”. 38 Many simply left andwent back home. Others jo<strong>in</strong>edspecial communist units to br<strong>in</strong>g therevolution to their homeland. Othersyet, mostly officers, were declared‘class enemies’ by the new regime,‘and had their salaries cut and werepromised only food’. 39 Gatrell tells usThe Bolsheviks attempted to organize Red Brigadesof ‘factional <strong>in</strong>fight<strong>in</strong>g among POWamong Ottoman soldiers, with little success amongradicals, some of whom threw theirArab prisoners.lot <strong>in</strong> with the Bolshevik Red Guardswhile others were committed to nonclassmilitias’. 40 At home, especially <strong>in</strong> Austria and Germany there was fear amongthe authorities that return<strong>in</strong>g prisoners from Russia, would be carry<strong>in</strong>g the ‘germs ofthe revolution’. 41 This fear was not without foundation s<strong>in</strong>ce the Bolsheviks began toorganize special units among Ottoman (as well as German and Austrian) war prisonersto carry out agitational work for socialism. 42 Several Ottoman soldiers and exiles, suchthe journalist Mustafa Subhi, jo<strong>in</strong>ed the Bolsheviks and established the Turkish RedBrigades, Turk Kizil Alayi, which <strong>in</strong>cluded about 1,000 men. 43 But apparently veryfew of the Arabs prisoners jo<strong>in</strong>ed. Aref does not even mention this group <strong>in</strong> his diary.Instead he and his comrades were determ<strong>in</strong>ed to jo<strong>in</strong> the Hijazi rebellion and fight forthe <strong>in</strong>dependence of the Arab K<strong>in</strong>gdom <strong>in</strong> Syria.Aref arrived to the Suez Canal five months after he left Krasnoyarsk, and crossed overto what had become British Occupied Palest<strong>in</strong>e. On his arrival he went straight to hisfather’s shop <strong>in</strong> the old city. His father had lost contact with any news of his son <strong>in</strong><strong>Siberia</strong> and was worried about Aref’s fate after the October events. He had grown oldand hardly recognized his son after the long absence. 44In Palest<strong>in</strong>e Aref jo<strong>in</strong>ed the ranks of the Faisali movement whose aim was to establishthe United K<strong>in</strong>gdom of the Arab East. He became a member of the newly formedArab Club (al Nadi al Arabi) as a branch of the Damascus group with the same name,and headed by scions of the <strong>Jerusalem</strong> former Ottoman elite—members of the AbulSu’ud, Budeiri, Husse<strong>in</strong>i, and Alami families. Its tw<strong>in</strong> objectives were unity of Syria,of which Palest<strong>in</strong>e was seen the southern part, and the struggle aga<strong>in</strong>st Zionism. 45 Itsma<strong>in</strong> rival <strong>in</strong> the nationalist movement was al Muntada Adabi, re-organized from theremnants of the Istanbul literary club, but now with the same objectives as al Nadial Arabi. By then its founder and Aref’s comrade, Abdul Karim al Khalil, had been[ 42 ] <strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>

hanged by Jamal Pasha <strong>in</strong> Beirut. The rupture with the Ottoman regime was nowcomplete. Both al Nadi and al Muntada, had active branches throughout Palest<strong>in</strong>e, andstrong connections with the same movement <strong>in</strong> Damascus.The Arab club (al Nadi) was headed by Jamil al Husse<strong>in</strong>i, an old comrade of al KhalilAbdul Karim, as well as Fakhri al Nashashibi, Boulus Shehadeh (editor of Mir’ata Sharq), Hasan Sidqi al Dajani, and Is’af al Nashashibi. It is <strong>in</strong> these two groupsthat the seeds of factional struggles with<strong>in</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>e, between the Husse<strong>in</strong>is, andthe Nashashibis orig<strong>in</strong>ated. 46 It is noteworthy that Aref, upon return<strong>in</strong>g to Palest<strong>in</strong>ewould jo<strong>in</strong> the Arab Club, and not the rejuvenated al Muntada Adabi to which heattributed the orig<strong>in</strong>s of his own Arabism when he was a young Ottoman officer. Thishas probably to do with the alliances and ideological orientations of each of thesetwo nascent movements. Both Porath and Bayan Nuwaihid-al Hut, suggest that theLiterary Club, which had only fa<strong>in</strong>t association with its Ottoman namesake (Jamil alHusse<strong>in</strong>i was a lead<strong>in</strong>g member of both), 47 was <strong>in</strong> contact, and perhaps association,with French <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> post-war Syria. In both rhetoric and programmatic objectivesal Muntada was strongly for Syrian unity, and aga<strong>in</strong>st the dissociation of Palest<strong>in</strong>efrom Syria. The Arab Club (<strong>in</strong> which Aref was <strong>in</strong>volved) was by contrast, allied to theBritish forces <strong>in</strong> the Middle East. This was a cont<strong>in</strong>uation (and perhaps an extensionof) the jo<strong>in</strong>t struggle coord<strong>in</strong>ated by the British and the Hashemites, and their Syrian-Palest<strong>in</strong>ian allies aga<strong>in</strong>st the retreat<strong>in</strong>g Ottomans, and for the re-organization of postwarBilad al Sham. 48 The British, <strong>in</strong> this regard, saw the Husse<strong>in</strong>is of <strong>Jerusalem</strong>, andHaj Am<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> particular, as their allies. It is paradoxical that with<strong>in</strong> two years, whenthe military government was replaced by the civilian Mandate authorities, these roleswould be reversed, and the Husse<strong>in</strong>is would become the ma<strong>in</strong> oppositional group<strong>in</strong> the country, while the Nashashibis and their allies became the balanc<strong>in</strong>g force ofBritish <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>e.These reversals expla<strong>in</strong> al Aref’s <strong>in</strong>itial wholehearted <strong>in</strong>volvement with al Nadi alArabi early <strong>in</strong> 1918, and his close association with the Husse<strong>in</strong>is. Al Aref experiencewith Ottoman journalism (Bayam) and with his clandest<strong>in</strong>e Naqat Allah <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>,came <strong>in</strong> handy. Together with Hasan al Budeiri he became the editor of Surya alJanubiyya (‘Southern Syria’), the organ of the al Nadi al Arabi, first published on 8 thSeptember, 1919. Both its name and editorials reflected a strong unity with Syria, andan assumption that the British would support this unity. 49 The motto of the newspaper(as well as the Arab Club), Biladuna Lana, which appeared on the top of everymasthead, referred to Syria, as the united homeland.Soon however, Surya al Janubiyya became an <strong>in</strong>strument of agitation aga<strong>in</strong>st Britishrule <strong>in</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>e, as British <strong>in</strong>tentions concern<strong>in</strong>g the aims of the Mandate becameclearer. Aref al Aref, who has adopted his new name by now, as editor <strong>in</strong> chief, wasoften a speaker <strong>in</strong> rallies aga<strong>in</strong>st the Balfour Declaration. (The picture shows a hugecrowd at Jaffa Street on 27 th February, 1920 <strong>in</strong> which the ma<strong>in</strong> banner declared<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 35 [ 43 ]

Aref al Aref, centre with Tarbush, address<strong>in</strong>g an anti-Zionist demonstration at Jaffa Street, <strong>Jerusalem</strong>on February 27th, 1920. The banner reads “Palest<strong>in</strong>e is an organic part of Southern Syria”. Source: ArefFamily Papers.“Palest<strong>in</strong>e is an essential part of Southern Syria”). The paper was suspended severaltimes, and an arrest order was issued aga<strong>in</strong>st Aref. He escaped to Damascus <strong>in</strong> 1920where he represented <strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>in</strong> the First Syrian Congress (al Mu’tamar al Suri)which declared Faisal to be the K<strong>in</strong>g of ‘natural Syria’. A military court <strong>in</strong> <strong>Jerusalem</strong>passed the death sentence on several nationalist figures, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Haj Am<strong>in</strong> alHusse<strong>in</strong>i and Aref al Aref, for ferment<strong>in</strong>g unrest. The sentence was later commuted toten years imprisonment.Muhammad Darwazeh, the future leader of the al Istiqlal party, met him <strong>in</strong> thisperiod of hot pursuit. “ I met Aref al Aref <strong>in</strong> Damascus when he, and Haj Am<strong>in</strong>,were seek<strong>in</strong>g refuge from British pursuit. He worked with us for the defense ofPalest<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the context of the Palest<strong>in</strong>e Secret Society [Jam’iyyat Filasteen alSirriyah]. I sensed <strong>in</strong> him a revolutionary spirit comb<strong>in</strong>ed with cool and balancedjudgment. He also impressed me with his command of Turkish and Arabic.” 50 InDamascus both Husse<strong>in</strong>i and Aref established the Palest<strong>in</strong>ian Arab Society (whichemerged from the ‘secret’ society referred to here by Darwazeh. It was establishedon May 31 st , 1920 under Haj Am<strong>in</strong>’s leadership and had Rafiq Tammimi, Mou<strong>in</strong>al Madi, and Awni Abdul Hadi, <strong>in</strong> addition to Darwazeh, and Aref <strong>in</strong> its executive.This was the historical moment—by most accounts—when Syrian and Palest<strong>in</strong>ianpolitics began to take separate ways. 51 The rupture was primarliy caused by Pr<strong>in</strong>ceFaisal and some of the lead<strong>in</strong>g figures <strong>in</strong> the Damascene Arab leadership whosought to ally themselves with the British aga<strong>in</strong>st the French objections to an<strong>in</strong>dependent Syria under Faisal. Rashid Khalidi po<strong>in</strong>ts out that <strong>in</strong> this alliance theSyrians sacrified their opposition to the Balfour Declaration (and therefore toneddown their struggle aga<strong>in</strong>st Zionism) with the hope that the British would support[ 44 ] <strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>

Syrian <strong>in</strong>dependence. “This approach”,Khalidi concludes, “produced a reaction frommany Palest<strong>in</strong>ians <strong>in</strong> Damascus, who saw itas a betrayal of the wider Arab cause, and oftheir own country , to benefit narrow Syrian<strong>in</strong>terests.” 52Shortly after this split and the formation of the Palest<strong>in</strong>ian Arab Society <strong>in</strong> Damascus,both Aref and Husse<strong>in</strong>i were pardoned and allowed to go back to Palest<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>in</strong> a policyof cooptation <strong>in</strong>itiated by the new civilian government of Herbert Samuel, the firstHigh Commissioner of Palest<strong>in</strong>e.Aref, accord<strong>in</strong>g to Darwazeh, ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed his nationalist l<strong>in</strong>e, but “withdrew fromall political activities”. 53 This is a fleet<strong>in</strong>g assessment, but it is full of implications. It<strong>in</strong>dicates that Aref, hav<strong>in</strong>g come to the conclusion that the fate of Palest<strong>in</strong>e was nowseparate from Syria by virtue of the imperial divisions imposed by Brita<strong>in</strong> and France,was now resigned to work with<strong>in</strong> the system. His career took a radical break with hisformer self as a fighter for Syrian unity. This also placed him <strong>in</strong> a different milieufrom other Arab Ottoman figures <strong>in</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>e, like Darwazeh, and Awni Abdul Hadi.From then on he became a senior adm<strong>in</strong>istrative officer <strong>in</strong> the Mandate Governmentbecom<strong>in</strong>g the District Officer (Qa’imaqam) of Gaza, Jen<strong>in</strong>, Nablus, Bisan, and Jaffa).For three crucial years he was sent by the Mandate government to be the M<strong>in</strong>isterialSecretary of the newly formed Government of Transjordan (1926-29), where he was awitness to the formation of the new Hashemite state.Residual OttomanismThis essay accompanied Lieutenant Shehadeh <strong>in</strong> his momentous journey from Ottoman<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>in</strong> 1908 to his military academy <strong>in</strong> Istanbul (1913) and to his capture and<strong>Siberia</strong>n exile for most of the great war (1915-1918). He stated <strong>in</strong> his diary that hediscovered his Arabness <strong>in</strong> the Literary Forum <strong>in</strong> Istanbul, where his comrades from theSyrian prov<strong>in</strong>ces were debat<strong>in</strong>g the future of their relationship with the new regime <strong>in</strong>Anatolia. “I was not aware that I was an Arab, and that I should th<strong>in</strong>k of the future ofmy Arab nation until the establishment of the al Muntada al Adabi <strong>in</strong> Istanbul” he wrotethen, “… It was then that I began to hear the words Arabs, Arabism, nationalism, andhomeland ”. His circle belonged to a number of political parties that emerged after the1908 Revolution—mostly to the CUP, but also to the Party of Ottoman Decentralization,and a small m<strong>in</strong>ority, to the secret al ‘Ahd group, which organized Arab officers <strong>in</strong>Istanbul for succession. But this new consciousness did not take Aref away from hisaff<strong>in</strong>ities, if not loyalty, to the Ottoman idea. He voluntarily went to fight for the FifthArmy on the Russian Front where he was captured and led to the <strong>in</strong>ternment camp <strong>in</strong>Krasnoyarsk. It was <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Siberia</strong>n exile, <strong>in</strong> the company of thousands of Turkish, Arab,<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 35 [ 45 ]

Balkan, and German soldiers, that he came around to develop a separate Arab politicalidentity, as opposed to the amorphous Arabist consciousness that he experienced <strong>in</strong>Istanbul. In the early period of <strong>in</strong>carceration there was a considerable degree of solidarityamong the various Ottoman ethnic groups, <strong>in</strong> which religious ceremonials, fast<strong>in</strong>gRamadan, and a feel<strong>in</strong>g of common dest<strong>in</strong>y played a significant role. Yanikdag refersto an event <strong>in</strong> late 1915 when a tea party was organized among Ottoman and Germansoldiers to jo<strong>in</strong>tly celebrate the military victory aga<strong>in</strong>st the allies <strong>in</strong> Gallipoli. 54 By theend of 1916 however the Arab officers and soldiers began to drift away. This rupturewith Ottoman identity among the Arabs was facilitated by political developments <strong>in</strong>Turkish Anatolia (primarily Turkification policies on the part of the Ottoman leadershipof the CUP), but <strong>in</strong> this case by three immediate factors discussed above: The campsegregated dwell<strong>in</strong>gs for Ottoman prisoners by ethnicity (and the implicit favoritismextended by the Russians towards Arab officers); the spread of clandest<strong>in</strong>e publicationslike Naqat Allah provid<strong>in</strong>g a separatist platform for Arab soldiers and officers; and(most importantly) news of the Hijazi Arab rebellion and the subsequent collapse of theOttoman fronts at Suez, Gaza, and southern Iraq (Kut al Amara). What was experiencedas a potential for emancipation of the Arab prov<strong>in</strong>ces from autocratic rule among Arabsoldiers, was seen as Arab betrayal by the Turkish soldiers.When Aref returned to Palest<strong>in</strong>e, his th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g was already set about jo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g therebellion and struggl<strong>in</strong>g for a separate Arab homeland. At least this is what he claimedlater on. Yet this rupture must have been gradual and protracted given that a visionfor a separate Arab homeland had not been fully formed. And the loom<strong>in</strong>g ‘betrayal’of the French and British allies was already visible to many Arab nationalists. Itwas particularly alarm<strong>in</strong>g to Palest<strong>in</strong>ians who had to face the prospects of fight<strong>in</strong>gseparately aga<strong>in</strong>st the Balfour Declaration. That factor <strong>in</strong> particular made many Arab<strong>in</strong>tellectuals reconsider their break with the Ottoman regime. But by that time theTurkish national movement had already moved away from a common future with itsArab prov<strong>in</strong>ces. Aref’s predicament was similar to another (and better known) fellowOttomanist, Sati al Husari, who was a devoted champion of Arab rights with<strong>in</strong> a CUPdom<strong>in</strong>ated Empire. Like Aref, Husari had a dual command of Arabic and Turkish,and both articulated the duality of Arab-Turkish identity <strong>in</strong> their early career. Unlikethe champions of a reformed Islamic Caliphate <strong>in</strong> Istanbul (people like Sheikh As’adal Shuqairi <strong>in</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>e), and fellow historian Ihsan al Nimr <strong>in</strong> Nablus, both Husariand Aref were champions of a secular Ottoman identity that derived much of its ideasfrom Western liberalism (francophone <strong>in</strong> the case of Husari, German <strong>in</strong> the case ofAref). This produced considerable ambivalence (if not regret) about break<strong>in</strong>g withthe Ottomans immediately after the war. Such ambivalence is not visible <strong>in</strong> the laterwrit<strong>in</strong>gs of Arab <strong>in</strong>tellectuals and political figures whose careers flourished <strong>in</strong> thepre-war period—where the rupture appears, <strong>in</strong> later reconstructions, as sudden andclear. Husari himself expressed this ambivalence about this period <strong>in</strong> a retrospective<strong>in</strong>terview, when he said, hesitantly, “I was an Arab, and when the Arabs broke awayfrom the Ottoman empire, I had no choice but to jo<strong>in</strong> them.” 55[ 46 ] <strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>

Nevertheless a residual Ottomanism wasreta<strong>in</strong>ed by a majority of these activists. Ama<strong>in</strong> feature of its persistence was language.In the spr<strong>in</strong>g of 1934, thirty years after Arefleft Istanbul to fight <strong>in</strong> the Caucasian Front,he received a love letter from his wife Sa’ema(Um Sufian) <strong>in</strong> <strong>Jerusalem</strong>. He was at thetime serv<strong>in</strong>g as District Officer <strong>in</strong> Gaza. UmSufian (Sa’ima) was compla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g about herlonel<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong> <strong>Jerusalem</strong>, and her long<strong>in</strong>g tosee Aref aga<strong>in</strong>. She wrote: 55...صبا حلين ايركن اوما ندم. باغجرية ايندم. براز دوالشدم . برازده صيجك قوماردم. دكزباغجرية نقلاولوم. بريمكلك لوبيه طويالدم. بن دوال شيركن هب فكربده سن بجوردك. سنسزهج برش كوزلىوكل. باغجرية تزين ايدن سنسك. مكر سنسزهج برسيده لذة يومد. اهلل من باشمدن اكسيكاينمه سون. بوتون حيا تمزى كوزل ايده سنك وجودك. بزون حركت ايتد يكك زمان براز نزله ايدك.فكرم شغول.رجا ايد بن تطمين ايت... سن بتون قليله سوه رفيقة حياتك. صائمةWhat is unique about this letter is the language. It was written <strong>in</strong> Ottoman Turkish,a language which by that time had ceased to exist by virtue of the Lat<strong>in</strong>izationprogram adopted by the Turkish Republic. Aref and his wife cont<strong>in</strong>ued to exchangecorrespondence <strong>in</strong> Ottoman, partly because they wanted to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a sense of privacy<strong>in</strong> their <strong>in</strong>timate exchanges, but equally I propose, because it was the language ofexpression that they grew up with and part of their cultural patrimony.Al Aref thus belongs to a generation of scholar-politicians whose successful Ottomancareer (journalist <strong>in</strong> the Turkish press, civil servant, and officer) was radicallydisrupted by war, compell<strong>in</strong>g him to reth<strong>in</strong>k his national identity, his future career asa soldier, and his ideological commitments as a political activist. But the rupture wasnot as total as it appears by his post-war writ<strong>in</strong>gs. His journalistic tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Istanbulproved to be an <strong>in</strong>valuable tool for his clandest<strong>in</strong>e writ<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong> (Naqat Allah),and <strong>in</strong> his editorship of the Surya al Janubiyya (the organ call<strong>in</strong>g for a greater SyrianArab state). And the debates he was engaged <strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong> the literary-political circles of theOttoman capital, were crucial for his political struggles dur<strong>in</strong>g the Faisali period <strong>in</strong>Damascus, and <strong>in</strong> Palest<strong>in</strong>e aga<strong>in</strong>st the Balfour Declaration.But these struggles were eclipsed by his accommodations to the new realities of theMandate regime, and by the shift he made with<strong>in</strong> three short years from advocacyof Arab-Syrian nationalism, to prov<strong>in</strong>cial Palest<strong>in</strong>ian patriotism. The significance of<strong>Siberia</strong>n imprisonment for Aref’s political trajectory is that it gave him a breath<strong>in</strong>gspace, and—paradoxically—a doma<strong>in</strong> of freedom <strong>in</strong> exile which allowed him toreformulate his future political options and past loyalties <strong>in</strong> a manner which wasdenied to most of his comrades.<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 35 [ 47 ]

A note on sources for Aref alAref <strong>Siberia</strong>n ExileKrasnoyarsk Days 1915-1918; Aref’s handwrittennotes <strong>in</strong> his photo album. Source: Aref FamilyCollection.Al Aref’s <strong>in</strong>ternment <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>presents a major challenge to theresearcher s<strong>in</strong>ce the ma<strong>in</strong> sourcefor Aref’s for this period, is anunpublished hand written diary whichis so far unavailable to the public.However his Photographic Album(In’ash al Usra Society Archives)conta<strong>in</strong>s sections from this diary, alsohandwritten, accompany<strong>in</strong>g his earlyphotographs, as well as the mastheadof Naqat al Jamal, that gives thereader an <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to the contentsof this diary. Another section of this diary was published <strong>in</strong> Aref’s Ru’yaii and <strong>in</strong> hisseparately published Biographic Notes (Mujaz Siratuh) listed below.1. Aref al Aref, My Days <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>: Diary; unpublished, unavailable, but listed <strong>in</strong> hislist of authored works. In Aref family possessions.2. Aref al Aref, Photographic Album, with biographic notes. In’ash al Usra Society, alBireh, unpublished.3. Correspondence of Ottoman Prisoner <strong>in</strong> Krasnoyarsk (<strong>Siberia</strong>) Lieutenant ArefShehadeh with his <strong>Jerusalem</strong> family <strong>in</strong> <strong>Jerusalem</strong>. In Alexander, Zvi. 2000.Osmanlı sahra postaları: Filist<strong>in</strong> (1914-1918) : Alexander Koleksiyonu. İstanbul:Türkiye Ekonomik ve Toplumsal Tarih Vakfı.4. Aref al Aref, Mujaz Siratuh 1892-1964, al Maaref Press, <strong>Jerusalem</strong>, 19645. Al Aref, Aref, Ru’yaii, (1918). First Edition, <strong>Jerusalem</strong>, 1943, n.p; second editionwith a new <strong>in</strong>troduction, Dar al Rihani, Beirut, 1957.6. Aref al Aref, Diary: Three Years <strong>in</strong> Amman (1926-29), unpublished manuscript,Institute for Palest<strong>in</strong>e Studies, Beirut.7. Aref al Aref, Gaza Diary (1934-1936) ; unpublished manuscript, St. Anthony’sCollege, Centre for Middle East Studies, library, Oxford University.Salim Tamari is the Editor of the <strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> and the Director of The Instituteof <strong>Jerusalem</strong> Studies.I am very grateful to Eugene Rogan and Debbie Usher at St Antony’s College, Oxford University, formak<strong>in</strong>g the Aref Diaries available to me, and to Mrs. Farideh al Amad for giv<strong>in</strong>g me access to the earlyphotographs and notes of Aref al Aref <strong>in</strong> Istanbul and <strong>Siberia</strong>, and to images of Naqat Allah. Thanks alsoto Muna Guvenc and Sibel Zandi-Sayek for help<strong>in</strong>g me with the Ottoman translations, and to PennyJohnson for her critical remarks.[ 48 ] <strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>

Endnotes1Ḥuṣrī , Abū Khaldūn Sāṭi’. 1966. The day ofMaysalūn; a page from the modern history ofthe Arabs; memoirs. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton: Middle EastInstitute.2In this essay I will use the two names<strong>in</strong>terchangeably: Aref Shehadeh for the warperiod, and Aref al Aref (which he assumedafter his return to Palest<strong>in</strong>e) for his reflections<strong>in</strong> the post-war period.3Muslih, Muhammad. The Orig<strong>in</strong>s ofPalest<strong>in</strong>ian Nationalism. New York: ColumbiaUniversity Press, 1988.4Aref al Aref, Mujaz Siratuh 1892-1964, alMaaref Press, <strong>Jerusalem</strong>, 1964; and Awdāt,Ya’qūb. 1987. M<strong>in</strong> a’lām al-fikr wa-al-adabfī Filasṭīn. ‘Amman: Wakālat al Tawzī ’ alUrdunī yah. Pp.400-403.5Awdat, Yaqoub, 406.6The source for his early years comes fromhis autobiographical essay, published as apamphlet. Aref al Aref, Mujaz Siratuh, op. cit.7Awdāt, Ya’qūb. 1987. M<strong>in</strong> a’lām al-fikrwa-al-adab fī Filasṭīn. ‘Amman: Wakālatal Tawzī ’ al Urdunīyah. P. 400. In Ru’yaii,he refers to the Mundtada <strong>in</strong> Istanbul, as theforum, “which we, Arabic speakers haveestablished <strong>in</strong> Asetanah, and <strong>in</strong> which we tookan oath to struggle for the freedom, unity and<strong>in</strong>dependence of our homeland”, p.5.8For details about the ideology of the ArabClub <strong>in</strong> Istanbul see, Muslih, Muhammad. TheOrig<strong>in</strong>s of Palest<strong>in</strong>ian Nationalism. op. cit.9Awdat, op. cit. p.405.10Awdat, ibid. p.400-401.11For a detailed discussion of Abdel Karim alKhalil and debates with the DecentralizationParty and the Arab club see Suhaila al Rimawi,“Pages from the history of Societies <strong>in</strong> Biladal Sham 1908-1918” <strong>in</strong> ‘Allūsh, Nājī, andIbrāhī m Ibrāsh. 1997. al Ḥarakah al ’Arabīyahal qawmīyah fī mi’at ‘ām, 1875-1982, pp.120-123 ‘Ammān: Dār al Shurūq.12Aref al Aref, Mujaz Siratuh, p.2-3 However themajor battle at Erzurum <strong>in</strong> which the Russianforces, led by the Grand Duke Nicholasdecisively defeated the Ottomans was foughton February 16, 1916. It is possible that Arefwas mistaken with the dates.13Al Aref, Aref, Ru’yaii, (1918). First Edition,<strong>Jerusalem</strong>, 1943, n.p; second edition with anew <strong>in</strong>troduction, Dar al Rihani, Beirut, 1957.All quotes here are from the second edition.14Yucel Yanikdag, “Ottoman Prisoners of War <strong>in</strong><strong>Siberia</strong>” Journal of Contemporary History, vol.34 no. 1, 1999; on the high rate of camp deathssee also Peter Gatrell (reference below), p.562.15See Peter Gatrell, “Prisoners of War <strong>in</strong> theEastern Front dur<strong>in</strong>g World War I”, Kritika:Explorations <strong>in</strong> Russian and East EurasianHistory 6, 3 (Summer 2005): pp.557-6616Ru’yaii, op cit., p.4.17Ibid. The paper actually was a jo<strong>in</strong>t productionwith fellow officer Ahmad al Kayyali.18These letters and postcards have been repr<strong>in</strong>ted<strong>in</strong> Alexander, Zvi. 2000. Osmanlı sahrapostaları: Filist<strong>in</strong> (1914-1918) : AlexanderKoleksiyonu. İstanbul: Türkiye Ekonomik veToplumsal Tarih Vakfı.19Peter Gatrell, “Prisoners of War”. Emphasisadded. Gatrell only addresses literature onGerman and Austro-Hungarian prisoners.20The expression was used by the Austrian writerHeimito von Doderer, quoted by Gatrell, ibid.p.563.21Yanikdag, op. cit.22Gatrell, p.561.23Yanikdag, p.73.24Yanikdag, p.77.25Yanikdag, p.75.26Yanikdag, p.74.27See Yanikdag, pp.76-77.28Yanikdag, p.77.29Aref al Aref Photo Album and Diary. In’ash alUsra. As far a I know only one issue of NaqatAllah, no. 35, has survived.30Qur’an, Hod: p.45. For details on the Qur’anicstory see al Ahsas web site. http://www.ahsas.net/vb/showthread.php?t=4611, cited onSeptember 1, 2008.31Yanikdag, p.77.32Awdat, p.401.33Aref al Aref, Mujaz Siratuh 1892-1964, alMaaref Press, <strong>Jerusalem</strong>, 1964, p.334Ru’yaii, p.5. Aref attributes the news to aletter he received from Rashid Rida, editor ofAlManar (Cairo). He <strong>in</strong>forms him that severalof his comrades from Istanbul days had jo<strong>in</strong>edSherif Husse<strong>in</strong> and were <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the siegeof Med<strong>in</strong>a.<strong>Jerusalem</strong> <strong>Quarterly</strong> 35 [ 49 ]

35Faridah Al Aref Al Amad, “Aref al Aref, MyFather”, al Turath wal Mujtama’, No. 41, July2005.36Al-Amad, ibid.37Gatrell, op. cit. p.564.38Yanikdag, p.80.39Ibid.40Gatrell, p.564-565.41Gatrell, p.565.42For the impact of the revolution on <strong>in</strong>ternaldissension among prisoners see Gatrell, ibid.p.564.43Yanikdag, p.81.44The encounter is told <strong>in</strong> Aref- al Amad, “Myfather Aref al Aref”, p.1.45Ḥūt, Bayān Nuwayhiḍ. 1981. Qiyādāt wa-almu’assasātal siyāsīyah fī Filasṭīn, 1917-1948.Bayrūt: Mu’assasat al Dirāsāt al Filasṭīnī yah.P. 86-87 . See also Darwazah, M. (1993).Mudhakkirāt Muḥammad ‘Izzat Darwazah,1305 H-1404 H/1887 M-1984 M: sijill ḥāfilbi-masīrat al ḥarakah al ’Arabīyah wa-alqaḍīyahal Filasṭīnīyah khilāla qarn m<strong>in</strong> alzaman. Bayrūt: Dār al Gharb al Islāmī. Vol 1,p.32646Muslih, op. cit.47Hut, op. cit. p.87.48Hut, pp. 86-89; Porath, Yehoshua. 1974. Theemergence of the Palest<strong>in</strong>ian-Arab nationalmovement, 1918-1929. London: Cass. pp.74-77.49See for example al Aref’s editorial <strong>in</strong> Suryaal Janubiyyah (unsigned), “Nadhra ila alGhad”, Volume 1, no. 48, March 26, 1920(6 Rajab, 1338).50Darwazah, op. cit. 326-327 Darwazeh wasprobably referr<strong>in</strong>g to Al Jam’yah Alarabbiyahal Filast<strong>in</strong>iyah (The Arab Palest<strong>in</strong>ian Society)which was dissem<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g anti-Zionist position<strong>in</strong> Damascus. See, Potath, op.cit. p.88.51Hut, op. cit. p.118.52Rashid Khalidi, The Iron Cage: The Story ofthe Palest<strong>in</strong>ian Struggle for Statehood, 2007,Boston, Beacon Press, pp.96-9753Darwazeh, ibid. p.326.54Yanikdag, p.74.55Quoted by Elias Sahhab, “Sati al Husari: the<strong>in</strong>tellectual and the activist”, <strong>in</strong> Naji Allush,The Arab National Movement <strong>in</strong> 100 Years,op.cit. p.409 Emphasis added.56Here is the English translation of the letter:I woke up early this morn<strong>in</strong>g. I walked around<strong>in</strong> the garden for a while. I picked up someflower and leaves.. I picked up some beans tocook for myself.. While I was mill<strong>in</strong>g around,you were always on my m<strong>in</strong>d. It is yourpresence that makes this garden beautiful.Noth<strong>in</strong>g has a taste without you. May God notdeprive me of your presence, for it is you whomakes my (our) life beautiful. When you left uslast time I noticed that you had a little cold... Iam th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about it. Let me know about yourhealth.Your life’s partner, who loves you with all herheart. Saema.I am very grateful to Sibel Sayk and MunaGuvenc for provid<strong>in</strong>g the translation fromOttoman Turkish.[ 50 ] <strong>With</strong> God’s <strong>Camel</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Siberia</strong>

![In Search of Jerusalem Airport [pdf] - Jerusalem Quarterly](https://img.yumpu.com/49007736/1/180x260/in-search-of-jerusalem-airport-pdf-jerusalem-quarterly.jpg?quality=85)