Schriften zu Genetischen Ressourcen - Genres

Schriften zu Genetischen Ressourcen - Genres Schriften zu Genetischen Ressourcen - Genres

B. PICKERSGILL, M.I. CHACÓN SÁNCHEZ and D.G. DEBOUCK parallel those in wild beans, and strongly suggest that beans were domesticated independently in Middle and South America, from local wild types (GEPTS et al. 1986, GEPTS 1990, KHAIRALLAH et al. 1992, BECERRA and GEPTS 1994). Tab. 1: Haplotypes found in landraces of common bean and their geographic distribution in wild common bean Haplotype C I K L Distribution in domesticated beans Andean gene pool (Races Nueva Granada, Peru and Chile) Mesoamerican gene pool (Races Mesoamerica and Guatemala) Mesoamerican gene pool (Races Mesoamerica and Durango) Mesoamerican gene pool (Races Mesoamerica, Durango and Jalisco) Geographic distribution in wild beans Central and southern Peru Southern Mexico; western, central and eastern Guatemala; eastern Honduras; central Colombia Northern Mexico; west-central and southern Mexico Western and central Mexico; western Guatemala; Costa Rica; Colombia It has also been suggested that P. vulgaris was domesticated more than once in each continent. In Mesoamerica, analysis of RAPDs (BEEBE et al. 2000) separated domesticated beans into groups which corresponded well to the three Mesoamerican races (Mesoamerica, Durango, Jalisco) recognised by SINGH et al. (1991). BEEBE et al. (2000) also recognised a fourth race (Guatemala) and considered that their RAPD data implied two or more domestications from distinct wild populations. However, Mesoamerican domesticated beans nearly all carry the S type of phaseolin even though more than 15 types of phaseolin are present in Mesoamerican wild beans (GEPTS and DEBOUCK 1991). GEPTS (1998) therefore argued that, in Mesoamerica, common beans were domesticated once only, in west central Mexico (Jalisco) where S phaseolin predominates among local wild beans, then diversified into the presentday races. In South America, Andean landraces have been classified into three further races (Nueva Granada, Peru, Chile) thought, like the Mesoamerican races, to represent distinct evolutionary lineages (SINGH et al. 1991). Several different phaseolins are present in these landraces, so GEPTS (1998) suggested multiple domestications in the Andean region. However, the DNA of Andean landraces has diverged very little, so BEEBE et al. (2001) argued that the three Andean races must have diversified after domestication. Chloroplast DNA has some advantages over nuclear DNA in studies of the domestication and spread of crop plants. It does not recombine, and is usually inherited 73

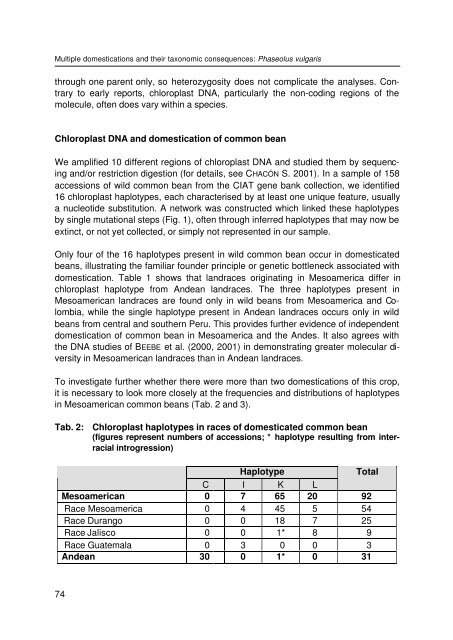

Multiple domestications and their taxonomic consequences: Phaseolus vulgaris through one parent only, so heterozygosity does not complicate the analyses. Contrary to early reports, chloroplast DNA, particularly the non-coding regions of the molecule, often does vary within a species. Chloroplast DNA and domestication of common bean We amplified 10 different regions of chloroplast DNA and studied them by sequencing and/or restriction digestion (for details, see CHACÓN S. 2001). In a sample of 158 accessions of wild common bean from the CIAT gene bank collection, we identified 16 chloroplast haplotypes, each characterised by at least one unique feature, usually a nucleotide substitution. A network was constructed which linked these haplotypes by single mutational steps (Fig. 1), often through inferred haplotypes that may now be extinct, or not yet collected, or simply not represented in our sample. Only four of the 16 haplotypes present in wild common bean occur in domesticated beans, illustrating the familiar founder principle or genetic bottleneck associated with domestication. Table 1 shows that landraces originating in Mesoamerica differ in chloroplast haplotype from Andean landraces. The three haplotypes present in Mesoamerican landraces are found only in wild beans from Mesoamerica and Colombia, while the single haplotype present in Andean landraces occurs only in wild beans from central and southern Peru. This provides further evidence of independent domestication of common bean in Mesoamerica and the Andes. It also agrees with the DNA studies of BEEBE et al. (2000, 2001) in demonstrating greater molecular diversity in Mesoamerican landraces than in Andean landraces. To investigate further whether there were more than two domestications of this crop, it is necessary to look more closely at the frequencies and distributions of haplotypes in Mesoamerican common beans (Tab. 2 and 3). Tab. 2: Chloroplast haplotypes in races of domesticated common bean (figures represent numbers of accessions; * haplotype resulting from interracial introgression) Haplotype Total C I K L Mesoamerican 0 7 65 20 92 Race Mesoamerica 0 4 45 5 54 Race Durango 0 0 18 7 25 Race Jalisco 0 0 1* 8 9 Race Guatemala 0 3 0 0 3 Andean 30 0 1* 0 31 74

- Page 33 and 34: Mansfeld's Encyclopedia of Agricult

- Page 35 and 36: Mansfeld's Encyclopedia of Agricult

- Page 37 and 38: Mansfeld's Encyclopedia of Agricult

- Page 39 and 40: Mansfeld's Encyclopedia of Agricult

- Page 41 and 42: Mansfeld's Encyclopedia of Agricult

- Page 43 and 44: The "Mansfeld Database" in its nati

- Page 45 and 46: The "Mansfeld Database" in its nati

- Page 47 and 48: A Species Compendium for Plant Gene

- Page 49 and 50: A Species Compendium for Plant Gene

- Page 51 and 52: A Species Compendium for Plant Gene

- Page 53 and 54: Some notes on problems of taxonomy

- Page 55 and 56: Some notes on problems of taxonomy

- Page 57 and 58: Some notes on problems of taxonomy

- Page 59 and 60: Some notes on problems of taxonomy

- Page 61 and 62: Some notes on problems of taxonomy

- Page 63 and 64: Theoretical and practical problems

- Page 65 and 66: Theoretical and practical problems

- Page 67 and 68: Theoretical and practical problems

- Page 69 and 70: Theoretical and practical problems

- Page 71 and 72: Development of Vavilov’s concept

- Page 73 and 74: Development of Vavilov’s concept

- Page 75 and 76: Development of Vavilov’s concept

- Page 77 and 78: Development of Vavilov’s concept

- Page 79 and 80: Development of Vavilov’s concept

- Page 81 and 82: Development of Vavilov’s concept

- Page 83: Multiple domestications and their t

- Page 87 and 88: Multiple domestications and their t

- Page 89 and 90: Multiple domestications and their t

- Page 91 and 92: Multiple domestications and their t

- Page 93 and 94: Multiple domestications and their t

- Page 95 and 96: Ethnobotanical studies on cultivate

- Page 97 and 98: Ethnobotanical studies on cultivate

- Page 99 and 100: Ethnobotanical studies on cultivate

- Page 101 and 102: Ethnobotanical studies on cultivate

- Page 103 and 104: Ethnobotanical studies on cultivate

- Page 105 and 106: Ethnobotanical studies on cultivate

- Page 107 and 108: Ethnobotanical studies on cultivate

- Page 109 and 110: Inventorying food plants in France

- Page 111 and 112: Inventorying food plants in France

- Page 113 and 114: Inventorying food plants in France

- Page 115 and 116: Inventorying food plants in France

- Page 117 and 118: Inventorying food plants in France

- Page 119 and 120: The neglected diversity of immigran

- Page 121 and 122: The neglected diversity of immigran

- Page 123 and 124: The neglected diversity of immigran

- Page 125 and 126: The neglected diversity of immigran

- Page 127 and 128: The neglected diversity of immigran

- Page 129 and 130: The neglected diversity of immigran

- Page 131 and 132: The neglected diversity of immigran

- Page 133 and 134: Unconscious selection in plants und

Multiple domestications and their taxonomic consequences: Phaseolus vulgaris<br />

through one parent only, so heterozygosity does not complicate the analyses. Contrary<br />

to early reports, chloroplast DNA, particularly the non-coding regions of the<br />

molecule, often does vary within a species.<br />

Chloroplast DNA and domestication of common bean<br />

We amplified 10 different regions of chloroplast DNA and studied them by sequencing<br />

and/or restriction digestion (for details, see CHACÓN S. 2001). In a sample of 158<br />

accessions of wild common bean from the CIAT gene bank collection, we identified<br />

16 chloroplast haplotypes, each characterised by at least one unique feature, usually<br />

a nucleotide substitution. A network was constructed which linked these haplotypes<br />

by single mutational steps (Fig. 1), often through inferred haplotypes that may now be<br />

extinct, or not yet collected, or simply not represented in our sample.<br />

Only four of the 16 haplotypes present in wild common bean occur in domesticated<br />

beans, illustrating the familiar founder principle or genetic bottleneck associated with<br />

domestication. Table 1 shows that landraces originating in Mesoamerica differ in<br />

chloroplast haplotype from Andean landraces. The three haplotypes present in<br />

Mesoamerican landraces are found only in wild beans from Mesoamerica and Colombia,<br />

while the single haplotype present in Andean landraces occurs only in wild<br />

beans from central and southern Peru. This provides further evidence of independent<br />

domestication of common bean in Mesoamerica and the Andes. It also agrees with<br />

the DNA studies of BEEBE et al. (2000, 2001) in demonstrating greater molecular diversity<br />

in Mesoamerican landraces than in Andean landraces.<br />

To investigate further whether there were more than two domestications of this crop,<br />

it is necessary to look more closely at the frequencies and distributions of haplotypes<br />

in Mesoamerican common beans (Tab. 2 and 3).<br />

Tab. 2: Chloroplast haplotypes in races of domesticated common bean<br />

(figures represent numbers of accessions; * haplotype resulting from interracial<br />

introgression)<br />

Haplotype<br />

Total<br />

C I K L<br />

Mesoamerican 0 7 65 20 92<br />

Race Mesoamerica 0 4 45 5 54<br />

Race Durango 0 0 18 7 25<br />

Race Jalisco 0 0 1* 8 9<br />

Race Guatemala 0 3 0 0 3<br />

Andean 30 0 1* 0 31<br />

74